The Fourteenth Amendment (Amendment XIV) to the United States Constitution was adopted on July 9, 1868, as one of the Reconstruction Amendments. The amendment addresses citizenship rights and equal protection of the laws and was proposed in response to issues related to former slaves following the American Civil War. The amendment was bitterly contested, particularly by the states of the defeated Confederacy, which were forced to ratify it in order to regain representation in Congress. The amendment, particularly its first section, is one of the most litigated parts of the Constitution, forming the basis for landmark decisions such as Brown v. Board of Education (1954) regarding racial segregation, Roe v. Wade (1973) regarding abortion, Bush v. Gore (2000) regarding the 2000 presidential election, and Obergefell v. Hodges (2015) regarding same-sex marriage. The amendment limits the actions of all state and local officials, including those acting on behalf of such an official.

The amendment's first section includes several clauses: the Citizenship Clause, Privileges or Immunities Clause, Due Process Clause, and Equal Protection Clause. The Citizenship Clause provides a broad definition of citizenship, nullifying the Supreme Court's decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), which had held that Americans descended from African slaves could not be citizens of the United States. The Privileges or Immunities Clause has been interpreted in such a way that it does very little.

The Due Process Clause prohibits state and local government officials from depriving persons of life, liberty, or property without legislative authorization. This clause has also been used by the federal judiciary to make most of the Bill of Rights applicable to the states, as well as to recognize substantive and procedural requirements that state laws must satisfy. The Equal Protection Clause requires each state to provide equal protection under the law to all people, including all non-citizens, within its jurisdiction. This clause has been the basis for many decisions rejecting irrational or unnecessary discrimination against people belonging to various groups.

The second, third, and fourth sections of the amendment are seldom litigated. However, the second section's reference to "rebellion and other crime" has been invoked as a constitutional ground for felony disenfranchisement. The fourth section was held, in Perry v. United States (1935), to prohibit a current Congress from abrogating a contract of debt incurred by a prior Congress. The fifth section gives Congress the power to enforce the amendment's provisions by "appropriate legislation"; however, under City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), this power may not be used to contradict a Supreme Court decision interpreting the amendment.

Text

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Section 2. Representatives shall be apportioned among the several States according to their respective numbers, counting the whole number of persons in each State, excluding Indians not taxed. But when the right to vote at any election for the choice of electors for President and Vice President of the United States, Representatives in Congress, the Executive and Judicial officers of a State, or the members of the Legislature thereof, is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, or in any way abridged, except for participation in rebellion, or other crime, the basis of representation therein shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall bear to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.

Section 3. No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may, by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

Section 4. The validity of the public debt of the United States, authorized by law, including debts incurred for payment of pensions and bounties for services in suppressing insurrection or rebellion, shall not be questioned. But neither the United States nor any State shall assume or pay any debt or obligation incurred in aid of insurrection or rebellion against the United States, or any claim for the loss or emancipation of any slave; but all such debts, obligations and claims shall be held illegal and void.

Section 5. The Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

Adoption

Proposal by Congress

In the final years of the American Civil War and the Reconstruction Era that followed, Congress repeatedly debated the rights of black former slaves freed by the 1863 Emancipation Proclamation and the 1865 Thirteenth Amendment, the latter of which had formally abolished slavery. Following the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment by Congress, however, Republicans grew concerned over the increase it would create in the congressional representation of the Democratic-dominated Southern States. Because the full population of freed slaves would now be counted for determining congressional representation, rather than the three-fifths previously mandated by the Three-Fifths Compromise, the Southern States would dramatically increase their power in the population-based House of Representatives, regardless of whether the former slaves were allowed to vote. Republicans began looking for a way to offset this advantage, either by protecting and attracting votes of former slaves, or at least by discouraging their disenfranchisement.In 1865, Congress passed what would become the Civil Rights Act of 1866, guaranteeing citizenship without regard to race, color, or previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude. The bill also guaranteed equal benefits and access to the law, a direct assault on the Black Codes passed by many post-war states. The Black Codes attempted to return ex-slaves to something like their former condition by, among other things, restricting their movement, forcing them to enter into year-long labor contracts, prohibiting them from owning firearms, and preventing them from suing or testifying in court.

Although strongly urged by moderates in Congress to sign the bill, President Andrew Johnson vetoed it on March 27, 1866. In his veto message, he objected to the measure because it conferred citizenship on the freedmen at a time when 11 out of 36 states were unrepresented in the Congress, and that it discriminated in favor of African-Americans and against whites. Three weeks later, Johnson's veto was overridden and the measure became law. Despite this victory, even some Republicans who had supported the goals of the Civil Rights Act began to doubt that Congress really possessed constitutional power to turn those goals into laws. The experience also encouraged both radical and moderate Republicans to seek Constitutional guarantees for black rights, rather than relying on temporary political majorities.

Over 70 proposals for an amendment were drafted. In late 1865, the Joint Committee on Reconstruction proposed an amendment stating that any citizens barred from voting on the basis of race by a state would not be counted for purposes of representation of that state. This amendment passed the House, but was blocked in the Senate by a coalition of Radical Republicans led by Charles Sumner, who believed the proposal a "compromise with wrong", and Democrats opposed to black rights. Consideration then turned to a proposed amendment by Representative John A. Bingham of Ohio, which would enable Congress to safeguard "equal protection of life, liberty, and property" of all citizens; this proposal failed to pass the House. In April 1866, the Joint Committee forwarded a third proposal to Congress, a carefully negotiated compromise that combined elements of the first and second proposals as well as addressing the issues of Confederate debt and voting by ex-Confederates. The House of Representatives passed House Resolution 127, 39th Congress several weeks later and sent to the Senate for action. The resolution was debated and several amendments to it were proposed. Amendments to Sections 2, 3, and 4 were adopted on June 8, 1866, and the modified resolution passed by a 33 to 11 vote. The House agreed to the Senate amendments on June 13 by a 138–36 vote. A concurrent resolution requesting the President to transmit the proposal to the executives of the several states was passed by both houses of Congress on June 18.

The Radical Republicans were satisfied that they had secured civil rights for blacks, but were disappointed that the amendment would not also secure political rights for blacks; in particular, the right to vote. For example, Thaddeus Stevens, a leader of the disappointed Radical Republicans, said: "I find that we shall be obliged to be content with patching up the worst portions of the ancient edifice, and leaving it, in many of its parts, to be swept through by the tempests, the frosts, and the storms of despotism." Abolitionist Wendell Phillips called it a "fatal and total surrender". This point would later be addressed by the Fifteenth Amendment.

Ratification by the states

Ratified amendment pre-certification, 1866–1868

Ratified amendment pre-certification after first rejecting it, 1868

Ratified amendment post-certification after first rejecting it, 1869–1976

Ratified amendment post-certification, 1959

Ratified amendment, withdrew ratification (rescission), then re-ratified. Oregon rescinded ratification post-certification and was included in the official count

Territories of the United States in 1868, not yet states

Ratification of the amendment was bitterly contested. State legislatures in every formerly Confederate state, with the exception of Tennessee, refused to ratify it. This refusal led to the passage of the Reconstruction Acts. Ignoring the existing state governments, military government was imposed until new civil governments were established and the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified. It also prompted Congress to pass a law on March 2, 1867, requiring that a former Confederate state must ratify the Fourteenth Amendment before "said State shall be declared entitled to representation in Congress".

The first twenty-eight states to ratify the Fourteenth Amendment were:

- Connecticut – June 30, 1866

- New Hampshire – July 6, 1866

- Tennessee – July 18, 1866

- New Jersey – September 11, 1866 (rescinded ratification – February 20, 1868/March 24, 1868; re-ratified – April 23, 2003)

- Oregon – September 19, 1866 (rescinded ratification – October 16, 1868; re-ratified – April 25, 1973)

- Vermont – October 30, 1866

- New York – January 10, 1867

- Ohio – January 11, 1867 (rescinded ratification – January 13, 1868; re-ratified – March 12, 2003)

- Illinois – January 15, 1867

- West Virginia – January 16, 1867

- Michigan – January 16, 1867

- Minnesota – January 16, 1867

- Kansas – January 17, 1867

- Maine – January 19, 1867

- Nevada – January 22, 1867

- Indiana – January 23, 1867

- Missouri – January 25, 1867

- Pennsylvania – February 6, 1867

- Rhode Island – February 7, 1867

- Wisconsin – February 13, 1867

- Massachusetts – March 20, 1867

- Nebraska – June 15, 1867

- Iowa – March 16, 1868

- Arkansas – April 6, 1868

- Florida – June 9, 1868

- North Carolina – July 4, 1868 (after rejection – December 14, 1866)

- Louisiana – July 9, 1868 (after rejection – February 6, 1867)

- South Carolina – July 9, 1868 (after rejection – December 20, 1866)

- Alabama – July 13, 1868

On the same day, one more State ratified:

- Georgia – July 21, 1868 (after rejection – November 9, 1866)

The inclusion of Ohio and New Jersey has led some to question the validity of rescission of a ratification. The inclusion of Alabama and Georgia has called that conclusion into question. While there have been Supreme Court cases dealing with ratification issues, this particular question has never been adjudicated.

The Fourteenth Amendment was subsequently ratified:

- Virginia – October 8, 1869 (after rejection – January 9, 1867)

- Mississippi – January 17, 1870

- Texas – February 18, 1870 (after rejection – October 27, 1866)

- Delaware – February 12, 1901 (after rejection – February 8, 1867)

- Maryland – April 4, 1959[28] (after rejection – March 23, 1867)

- California – May 6, 1959

- Kentucky – March 30, 1976 (after rejection – January 8, 1867)

Citizenship and civil rights

Background

Section 1 of the amendment formally defines United States citizenship and also protects various civil rights from being abridged or denied by any state or state actor. Abridgment or denial of those civil rights by private persons is not addressed by this amendment; the Supreme Court held in the Civil Rights Cases (1883) that the amendment was limited to "state action" and, therefore, did not authorize the Congress to outlaw racial discrimination by private individuals or organizations (though Congress can sometimes reach such discrimination via other parts of the Constitution). U.S. Supreme Court Justice Joseph P. Bradley commented in the Civil Rights Cases that "individual invasion of individual rights is not the subject-matter of the [14th] Amendment. It has a deeper and broader scope. It nullifies and makes void all state legislation, and state action of every kind, which impairs the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, or which injures them in life, liberty or property without due process of law, or which denies to any of them the equal protection of the laws."The Radical Republicans who advanced the Thirteenth Amendment hoped to ensure broad civil and human rights for the newly freed people—but its scope was disputed before it even went into effect. The framers of the Fourteenth Amendment wanted these principles enshrined in the Constitution to protect the new Civil Rights Act from being declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court and also to prevent a future Congress from altering it by a mere majority vote. This section was also in response to violence against black people within the Southern States. The Joint Committee on Reconstruction found that only a Constitutional amendment could protect black people's rights and welfare within those states.

This first section of the amendment has been the most frequently litigated part of the amendment, and this amendment in turn has been the most frequently litigated part of the Constitution.

Citizenship Clause

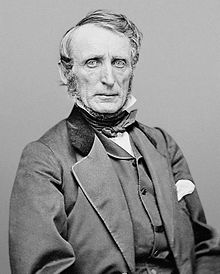

U.S. Senator from Michigan Jacob M. Howard, author of the Citizenship Clause

The Citizenship Clause overruled the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision that black people were not citizens and could not become citizens, nor enjoy the benefits of citizenship. Some members of Congress voted for the Fourteenth Amendment in order to eliminate doubts about the constitutionality of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, or to ensure that no subsequent Congress could later repeal or alter the main provisions of that Act. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 had granted citizenship to all persons born in the United States if they were not subject to a foreign power, and this clause of the Fourteenth Amendment constitutionalized this rule.

There are varying interpretations of the original intent of Congress and of the ratifying states, based on statements made during the congressional debate over the amendment, as well as the customs and understandings prevalent at that time. Some of the major issues that have arisen about this clause are the extent to which it included Native Americans, its coverage of non-citizens legally present in the United States when they have a child, whether the clause allows revocation of citizenship, and whether the clause applies to illegal immigrants.

Historian Eric Foner, who has explored the question of U.S. birthright citizenship to other countries, argues that:

Many things claimed as uniquely American—a devotion to individual freedom, for example, or social opportunity—exist in other countries. But birthright citizenship does make the United States (along with Canada) unique in the developed world. [...] Birthright citizenship is one expression of the commitment to equality and the expansion of national consciousness that marked Reconstruction. [...] Birthright citizenship is one legacy of the titanic struggle of the Reconstruction era to create a genuine democracy grounded in the principle of equality.

Native Americans

During the original congressional debate over the amendment Senator Jacob M. Howard of Michigan—the author of the Citizenship Clause—described the clause as having the same content, despite different wording, as the earlier Civil Rights Act of 1866, namely, that it excludes Native Americans who maintain their tribal ties and "persons born in the United States who are foreigners, aliens, who belong to the families of ambassadors or foreign ministers." According to historian Glenn W. LaFantasie of Western Kentucky University, "A good number of his fellow senators supported his view of the citizenship clause." Others also agreed that the children of ambassadors and foreign ministers were to be excluded.Senator James Rood Doolittle of Wisconsin asserted that all Native Americans were subject to United States jurisdiction, so that the phrase "Indians not taxed" would be preferable, but Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Lyman Trumbull and Howard disputed this, arguing that the federal government did not have full jurisdiction over Native American tribes, which govern themselves and make treaties with the United States. In Elk v. Wilkins (1884), the clause's meaning was tested regarding whether birth in the United States automatically extended national citizenship. The Supreme Court held that Native Americans who voluntarily quit their tribes did not automatically gain national citizenship. The issue was resolved with the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted full U.S. citizenship to indigenous peoples.

Children born to citizens of other countries

The Fourteenth Amendment provides that children born in the United States and subject to its jurisdiction become American citizens at birth. At the time of the amendment's passage, three Senators, including Trumbull, the author of the Civil Rights Act, as well as President Andrew Johnson, asserted that both the Civil Rights Act and the Fourteenth Amendment would confer citizenship at birth on children born in the United States to citizens of foreign countries; however, Senator Edgar Cowan of Pennsylvania had a definitively contrary opinion. These congressional remarks applied to non-citizens lawfully present in the United States, as the problem of unauthorized immigration did not exist in 1866, and some scholars dispute whether the Citizenship Clause applies to unauthorized immigrants, although the law of the land continues to be based on the standard interpretation. Congress during the 21st century has occasionally discussed revising the clause to reduce the practice of "birth tourism", in which a pregnant foreign national gives birth in the United States for purposes of the child's citizenship.The clause's meaning with regard to a child of legal immigrants was tested in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898). The Supreme Court held that under the Fourteenth Amendment, a man born within the United States to Chinese citizens who have a permanent domicile and residence in the United States and are carrying on business in the United States—and whose parents were not employed in a diplomatic or other official capacity by a foreign power—was a citizen of the United States. Subsequent decisions have applied the principle to the children of foreign nationals of non-Chinese descent.

According to the Foreign Affairs Manual, which is published by the Department of Defense, "Despite widespread popular belief, U.S. military installations abroad and U.S. diplomatic or consular facilities abroad are not part of the United States within the meaning of the [Fourteenth] Amendment."

Loss of citizenship

Loss of national citizenship is possible only under the following circumstances:- Fraud in the naturalization process. Technically, this is not a loss of citizenship but rather a voiding of the purported naturalization and a declaration that the immigrant never was a citizen of the United States.

- Affiliation with "anti-American" organizations (e.g., the Communist party, terrorist organizations, etc.) within 5 years of naturalization. The State department views such affiliations as sufficient evidence that an applicant must have lied or concealed evidence in the naturalization process.

- Other-than-honorable discharge from the U.S. armed forces before 5 years of honorable service, if honorable service was the basis for the naturalization.

- Voluntary relinquishment of citizenship. This may be accomplished either through renunciation procedures specially established by the State Department or through other actions that demonstrate desire to give up national citizenship.

Privileges or Immunities Clause

The Privileges or Immunities Clause, which protects the privileges and immunities of national citizenship from interference by the states, was patterned after the Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV, which protects the privileges and immunities of state citizenship from interference by other states. In the Slaughter-House Cases (1873), the Supreme Court concluded that the Constitution recognized two separate types of citizenship—"national citizenship" and "state citizenship"—and the Court held that the Privileges or Immunities Clause prohibits states from interfering only with privileges and immunities possessed by virtue of national citizenship. The Court concluded that the privileges and immunities of national citizenship included only those rights that "owe their existence to the Federal government, its National character, its Constitution, or its laws." The Court recognized few such rights, including access to seaports and navigable waterways, the right to run for federal office, the protection of the federal government while on the high seas or in the jurisdiction of a foreign country, the right to travel to the seat of government, the right to peaceably assemble and petition the government, the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, and the right to participate in the government's administration. This decision has not been overruled and has been specifically reaffirmed several times. Largely as a result of the narrowness of the Slaughter-House opinion, this clause subsequently lay dormant for well over a century.In Saenz v. Roe (1999), the Court ruled that a component of the "right to travel" is protected by the Privileges or Immunities Clause:

Despite fundamentally differing views concerning the coverage of the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, most notably expressed in the majority and dissenting opinions in the Slaughter-House Cases (1873), it has always been common ground that this Clause protects the third component of the right to travel. Writing for the majority in the Slaughter-House Cases, Justice Miller explained that one of the privileges conferred by this Clause "is that a citizen of the United States can, of his own volition, become a citizen of any State of the Union by a bona fide residence therein, with the same rights as other citizens of that State." (emphasis added)Justice Miller actually wrote in the Slaughter-House Cases that the right to become a citizen of a state (by residing in that state) "is conferred by the very article under consideration" (emphasis added), rather than by the "clause" under consideration.

In McDonald v. Chicago (2010), Justice Clarence Thomas, while concurring with the majority in incorporating the Second Amendment against the states, declared that he reached this conclusion through the Privileges or Immunities Clause instead of the Due Process Clause. Randy Barnett has referred to Justice Thomas's concurring opinion as a "complete restoration" of the Privileges or Immunities Clause.

Due Process Clause

In the 1884 case of Hurtado v. California, the U.S. Supreme Court said:Due process of law in the [Fourteenth Amendment] refers to that law of the land in each state which derives its authority from the inherent and reserved powers of the state, exerted within the limits of those fundamental principles of liberty and justice which lie at the base of all our civil and political institutions, and the greatest security for which resides in the right of the people to make their own laws, and alter them at their pleasure.The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment applies only against the states, but it is otherwise textually identical to the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, which applies against the federal government; both clauses have been interpreted to encompass identical doctrines of procedural due process and substantive due process. Procedural due process is the guarantee of a fair legal process when the government tries to interfere with a person's protected interests in life, liberty, or property, and substantive due process is the guarantee that the fundamental rights of citizens will not be encroached on by government. The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment also incorporates most of the provisions in the Bill of Rights, which were originally applied against only the federal government, and applies them against the states.

Substantive due process

Beginning with Allgeyer v. Louisiana (1897), the Court interpreted the Due Process Clause as providing substantive protection to private contracts, thus prohibiting a variety of social and economic regulation; this principle was referred to as "freedom of contract." Thus, the Court struck down a law decreeing maximum hours for workers in a bakery in Lochner v. New York (1905) and struck down a minimum wage law in Adkins v. Children's Hospital (1923). In Meyer v. Nebraska (1923), the Court stated that the "liberty" protected by the Due Process Clause[w]ithout doubt...denotes not merely freedom from bodily restraint but also the right of the individual to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.However, the Court did uphold some economic regulation, such as state Prohibition laws (Mugler v. Kansas, 1887), laws declaring maximum hours for mine workers (Holden v. Hardy, 1898), laws declaring maximum hours for female workers (Muller v. Oregon, 1908), and President Woodrow Wilson's intervention in a railroad strike (Wilson v. New, 1917), as well as federal laws regulating narcotics (United States v. Doremus, 1919). The Court repudiated, but did not explicitly overrule, the "freedom of contract" line of cases in West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937).

In Poe v. Ullman (1961), dissenting judge John Marshall Harlan II adopted a broad view of the "liberty" protected by the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process clause:

[T]he full scope of the liberty guaranteed by the Due Process Clause cannot be found in or limited by the precise terms of the specific guarantees elsewhere provided in the Constitution. This 'liberty' is not a series of isolated points pricked out in terms of the taking of property; the freedom of speech, press, and religion; the right to keep and bear arms; the freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures; and so on. It is a rational continuum which, broadly speaking, includes a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions and purposeless restraints, . . . and which also recognizes, what a reasonable and sensitive judgment must, that certain interests require particularly careful scrutiny of the state needs asserted to justify their abridgment.This broad view of liberty was adopted by the Supreme Court in Griswold v. Connecticut (for further information see below). Although the "freedom of contract" described above has fallen into disfavor, by the 1960s, the Court had extended its interpretation of substantive due process to include other rights and freedoms that are not enumerated in the Constitution but that, according to the Court, extend or derive from existing rights. For example, the Due Process Clause is also the foundation of a constitutional right to privacy. The Court first ruled that privacy was protected by the Constitution in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), which overturned a Connecticut law criminalizing birth control. While Justice William O. Douglas wrote for the majority that the right to privacy was found in the "penumbras" of various provisions in the Bill of Rights, Justices Arthur Goldberg and John Marshall Harlan II wrote in concurring opinions that the "liberty" protected by the Due Process Clause included individual privacy.

The right to privacy was the basis for Roe v. Wade (1973), in which the Court invalidated a Texas law forbidding abortion except to save the mother's life. Like Goldberg's and Harlan's concurring opinions in Griswold, the majority opinion authored by Justice Harry Blackmun located the right to privacy in the Due Process Clause's protection of liberty. The decision disallowed many state and federal abortion restrictions, and it became one of the most controversial in the Court's history. In Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), the Court decided that "the essential holding of Roe v. Wade should be retained and once again reaffirmed."

In Lawrence v. Texas (2003), the Court found that a Texas law against same-sex sexual intercourse violated the right to privacy. In Obergefell v. Hodges (2015), the Court ruled that the fundamental right to marriage included same-sex couples being able to marry.

Procedural due process

When the government seeks to burden a person's protected liberty interest or property interest, the Supreme Court has held that procedural due process requires that, at a minimum, the government provide the person notice, an opportunity to be heard at an oral hearing, and a decision by a neutral decision maker. For example, such process is due when a government agency seeks to terminate civil service employees, expel a student from public school, or cut off a welfare recipient's benefits. The Court has also ruled that the Due Process Clause requires judges to recuse themselves in cases where the judge has a conflict of interest. For example, in Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co. (2009), the Court ruled that a justice of the Supreme Court of Appeals of West Virginia had to recuse himself from a case involving a major contributor to his campaign for election to that court.Incorporation

While many state constitutions are modeled after the United States Constitution and federal laws, those state constitutions did not necessarily include provisions comparable to the Bill of Rights. In Barron v. Baltimore (1833), the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that the Bill of Rights restrained only the federal government, not the states. However, the Supreme Court has subsequently held that most provisions of the Bill of Rights apply to the states through the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment under a doctrine called "incorporation."Whether incorporation was intended by the amendment's framers, such as John Bingham, has been debated by legal historians. According to legal scholar Akhil Reed Amar, the framers and early supporters of the Fourteenth Amendment believed that it would ensure that the states would be required to recognize the same individual rights as the federal government; all of these rights were likely understood as falling within the "privileges or immunities" safeguarded by the amendment.

By the latter half of the 20th century, nearly all of the rights in the Bill of Rights had been applied to the states. The Supreme Court has held that the amendment's Due Process Clause incorporates all of the substantive protections of the First, Second, Fourth, Fifth (except for its Grand Jury Clause) and Sixth Amendments and the Cruel and Unusual Punishment Clause of the Eighth Amendment. While the Third Amendment has not been applied to the states by the Supreme Court, the Second Circuit ruled that it did apply to the states within that circuit's jurisdiction in Engblom v. Carey. The Seventh Amendment right to jury trial in civil cases has been held not to be applicable to the states, but the amendment's Re-Examination Clause applies not only to federal courts, but also to "a case tried before a jury in a state court and brought to the Supreme Court on appeal."

On June 18, 2018, the Supreme Court agreed to hear Timbs v. Indiana. Timbs will decide whether the Excessive Fines Clause of the Eighth Amendment should be applied to the states.

Equal Protection Clause

Representative John Bingham of Ohio, principal author of the Equal Protection Clause

The Equal Protection Clause was created largely in response to the lack of equal protection provided by law in states with Black Codes. Under Black Codes, blacks could not sue, give evidence, or be witnesses. They also were punished more harshly than whites. In 1880, the Supreme Court stated in Strauder v. West Virginia that the Equal Protection Clause was

The Clause mandates that individuals in similar situations be treated equally by the law. Although the text of the Fourteenth Amendment applies the Equal Protection Clause only against the states, the Supreme Court, since Bolling v. Sharpe (1954), has applied the Clause against the federal government through the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment under a doctrine called "reverse incorporation."In Yick Wo v. Hopkins (1886), the Supreme Court has clarified that the meaning of "person" and "within its jurisdiction" in the Equal Protection Clause would not be limited to discrimination against African Americans, but would extend to other races, colors, and nationalities such as (in this case) legal aliens in the United States who are Chinese citizens:

These provisions are universal in their application to all persons within the territorial jurisdiction, without regard to any differences of race, of color, or of nationality, and the equal protection of the laws is a pledge of the protection of equal laws.Persons "within its jurisdiction" are entitled to equal protection from a state. Largely because the Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV has from the beginning guaranteed the privileges and immunities of citizens in the several states, the Supreme Court has rarely construed the phrase "within its jurisdiction" in relation to natural persons. In Plyler v. Doe (1982), where the Court held that aliens illegally present in a state are within its jurisdiction and may thus raise equal protection claims the Court explicated the meaning of the phrase "within its jurisdiction" as follows: "[U]se of the phrase "within its jurisdiction" confirms the understanding that the Fourteenth Amendment's protection extends to anyone, citizen or stranger, who is subject to the laws of a State, and reaches into every corner of a State's territory." The Court reached this understanding among other things from Senator Howard, a member of the Joint Committee of Fifteen, and the floor manager of the amendment in the Senate. Senator Howard was explicit about the broad objectives of the Fourteenth Amendment and the intention to make its provisions applicable to all who "may happen to be" within the jurisdiction of a state:

The last two clauses of the first section of the amendment disable a State from depriving not merely a citizen of the United States, but any person, whoever he may be, of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or from denying to him the equal protection of the laws of the State. This abolishes all class legislation in the States and does away with the injustice of subjecting one caste of persons to a code not applicable to another. ... It will, if adopted by the States, forever disable every one of them from passing laws trenching upon those fundamental rights and privileges which pertain to citizens of the United States, and to all person who may happen to be within their jurisdiction. [emphasis added by the U.S. Supreme Court]The relationship between the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments was addressed by Justice Field in Wong Wing v. United States (1896). He observed with respect to the phrase "within its jurisdiction": "The term 'person,' used in the Fifth Amendment, is broad enough to include any and every human being within the jurisdiction of the republic. A resident, alien born, is entitled to the same protection under the laws that a citizen is entitled to. He owes obedience to the laws of the country in which he is domiciled, and, as a consequence, he is entitled to the equal protection of those laws. ... The contention that persons within the territorial jurisdiction of this republic might be beyond the protection of the law was heard with pain on the argument at the bar—in face of the great constitutional amendment which declares that no State shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws."

The Supreme Court also decided whether foreign corporations are also within the jurisdiction of a state, ruling that a foreign corporation which sued in a state court in which it was not licensed to do business to recover possession of property wrongfully taken from it in another state was within the jurisdiction and could not be subjected to unequal burdens in the maintenance of the suit. When a state has admitted a foreign corporation to do business within its borders, that corporation is entitled to equal protection of the laws but not necessarily to identical treatment with domestic corporations.

In Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad (1886), the court reporter included a statement by Chief Justice Morrison Waite in the decision's headnote:

The court does not wish to hear argument on the question whether the provision in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution, which forbids a State to deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws, applies to these corporations. We are all of the opinion that it does.This dictum, which established that corporations enjoyed personhood under the Equal Protection Clause, was repeatedly reaffirmed by later courts. It remained the predominant view throughout the twentieth century, though it was challenged in dissents by justices such as Hugo Black and William O. Douglas. Between 1890 and 1910, Fourteenth Amendment cases involving corporations vastly outnumbered those involving the rights of blacks, 288 to 19.

In the decades following the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court overturned laws barring blacks from juries (Strauder v. West Virginia, 1880) or discriminating against Chinese Americans in the regulation of laundry businesses (Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 1886), as violations of the Equal Protection Clause. However, in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the Supreme Court held that the states could impose segregation so long as they provided similar facilities—the formation of the "separate but equal" doctrine.

The Court went even further in restricting the Equal Protection Clause in Berea College v. Kentucky (1908), holding that the states could force private actors to discriminate by prohibiting colleges from having both black and white students. By the early 20th century, the Equal Protection Clause had been eclipsed to the point that Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. dismissed it as "the usual last resort of constitutional arguments."

Thurgood Marshall served as chief counsel in the landmark Fourteenth Amendment decision Brown v. Board of Education (1954).

The Court held to the "separate but equal" doctrine for more than fifty years, despite numerous cases in which the Court itself had found that the segregated facilities provided by the states were almost never equal, until Brown v. Board of Education (1954) reached the Court. In Brown the Court ruled that even if segregated black and white schools were of equal quality in facilities and teachers, segregation was inherently harmful to black students and so was unconstitutional. Brown met with a campaign of resistance from white Southerners, and for decades the federal courts attempted to enforce Brown's mandate against repeated attempts at circumvention. This resulted in the controversial desegregation busing decrees handed down by federal courts in various parts of the nation. In Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007), the Court ruled that race could not be the determinative factor in determining to which public schools parents may transfer their children.

In Plyler v. Doe (1982) the Supreme Court struck down a Texas statute denying free public education to illegal immigrants as a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because discrimination on the basis of illegal immigration status did not further a substantial state interest. The Court reasoned that illegal aliens and their children, though not citizens of the United States or Texas, are people "in any ordinary sense of the term" and, therefore, are afforded Fourteenth Amendment protections.

In Hernandez v. Texas (1954), the Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment protects those beyond the racial classes of white or "Negro" and extends to other racial and ethnic groups, such as Mexican Americans in this case. In the half-century following Brown, the Court extended the reach of the Equal Protection Clause to other historically disadvantaged groups, such as women and illegitimate children, although it has applied a somewhat less stringent standard than it has applied to governmental discrimination on the basis of race (United States v. Virginia (1996); Levy v. Louisiana (1968)).

The Supreme Court ruled in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978) that affirmative action in the form of racial quotas in public university admissions was a violation of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964; however, race could be used as one of several factors without violating of the Equal Protection Clause or Title VI. In Gratz v. Bollinger (2003) and Grutter v. Bollinger (2003), the Court considered two race-conscious admissions systems at the University of Michigan. The university claimed that its goal in its admissions systems was to achieve racial diversity. In Gratz, the Court struck down a points-based undergraduate admissions system that added points for minority status, finding that its rigidity violated the Equal Protection Clause; in Grutter, the Court upheld a race-conscious admissions process for the university's law school that used race as one of many factors to determine admission. In Fisher v. University of Texas (2013), the Court ruled that before race can be used in a public university's admission policy, there must be no workable race-neutral alternative. In Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action (2014), the Court upheld the constitutionality of a state constitutional prohibition on the state or local use of affirmative action.

Reed v. Reed (1971), which struck down an Idaho probate law favoring men, was the first decision in which the Court ruled that arbitrary gender discrimination violated the Equal Protection Clause. In Craig v. Boren (1976), the Court ruled that statutory or administrative sex classifications had to be subjected to an intermediate standard of judicial review. Reed and Craig later served as precedents to strike down a number of state laws discriminating by gender.

Since Wesberry v. Sanders (1964) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the Supreme Court has interpreted the Equal Protection Clause as requiring the states to apportion their congressional districts and state legislative seats according to "one man, one vote". The Court has also struck down redistricting plans in which race was a key consideration. In Shaw v. Reno (1993), the Court prohibited a North Carolina plan aimed at creating majority-black districts to balance historic underrepresentation in the state's congressional delegations.

The Equal Protection Clause served as the basis for the decision in Bush v. Gore (2000), in which the Court ruled that no constitutionally valid recount of Florida's votes in the 2000 presidential election could be held within the needed deadline; the decision effectively secured Bush's victory in the disputed election. In League of United Latin American Citizens v. Perry (2006), the Court ruled that House Majority Leader Tom DeLay's Texas redistricting plan intentionally diluted the votes of Latinos and thus violated the Equal Protection Clause.

State actor doctrine

Individual liberties guaranteed by the United States Constitution, other than the Thirteenth Amendment's ban on slavery, protect not against actions by private persons or entities, but only against actions by government officials. Regarding the Fourteenth Amendment, the Supreme Court ruled in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948): "[T]he action inhibited by the first section of the Fourteenth Amendment is only such action as may fairly be said to be that of the States. That Amendment erects no shield against merely private conduct, however discriminatory or wrongful." The court added in Civil Rights Cases (1883): "It is State action of a particular character that is prohibited. Individual invasion of individual rights is not the subject matter of the amendment. It has a deeper and broader scope. It nullifies and makes void all State legislation, and State action of every kind, which impairs the privileges and immunities of citizens of the United States, or which injures them in life, liberty, or property without due process of law, or which denies to any of them the equal protection of the laws." Vindication of federal constitutional rights are limited to those situations where there is "state action" meaning action of government officials who are exercising their governmental power. In Ex parte Virginia (1880), the Supreme Court found that the prohibitions of the Fourteenth Amendment "have reference to actions of the political body denominated by a State, by whatever instruments or in whatever modes that action may be taken. A State acts by its legislative, its executive, or its judicial authorities. It can act in no other way. The constitutional provision, therefore, must mean that no agency of the State, or of the officers or agents by whom its powers are exerted, shall deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws. Whoever, by virtue of public position under a State government, deprives another of property, life, or liberty, without due process of law, or denies or takes away the equal protection of the laws, violates the constitutional inhibition; and as he acts in the name and for the State, and is clothed with the State's power, his act is that of the State."There are however instances where people are the victims of civil-rights violations that occur in circumstances involving both government officials and private actors. In the 1960s, the United States Supreme Court adopted an expansive view of state action opening the door to wide-ranging civil-rights litigation against private actors when they act as state actors (i.e., acts done or otherwise "sanctioned in some way" by the state). The Court found that the state action doctrine is equally applicable to denials of privileges or immunities, due process, and equal protection of the laws.

The critical factor in determining the existence of state action is not governmental involvement with private persons or private corporations, but "the inquiry must be whether there is a sufficiently close nexus between the State and the challenged action of the regulated entity so that the action of the latter may be fairly treated as that of the State itself." "Only by sifting facts and weighing circumstances can the nonobvious involvement of the State in private conduct be attributed its true significance."

The Supreme Court asserted that plaintiffs must establish not only that a private party "acted under color of the challenged statute, but also that its actions are properly attributable to the State. [...]" "And the actions are to be attributable to the State apparently only if the State compelled the actions and not if the State merely established the process through statute or regulation under which the private party acted."

The rules developed by the Supreme Court for business regulation are that (1) the "mere fact that a business is subject to state regulation does not by itself convert its action into that of the State for purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment," and (2) "a State normally can be held responsible for a private decision only when it has exercised coercive power or has provided such significant encouragement, either overt or covert, that the choice must be deemed to be that of the State."

Apportionment of representation in House of Representatives

Under Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, the basis of representation of each state in the House of Representatives was determined by adding three-fifths of each state's slave population to its free population. Because slavery (except as punishment for crime) had been abolished by the Thirteenth Amendment, the freed slaves would henceforth be given full weight for purposes of apportionment. This situation was a concern to the Republican leadership of Congress, who worried that it would increase the political power of the former slave states, even as they continued to deny freed slaves the right to vote.Two solutions were considered:

- reduce the Congressional representation of the former slave states (for example, by basing representation on the number of legal voters rather than the number of inhabitants)

- guarantee freed slaves the right to vote

The effect of Section 2 was twofold:

- Although the three-fifths clause was not formally repealed, it was effectively removed from the Constitution. In the words of the Supreme Court in Elk v. Wilkins, Section 2 "abrogated so much of the corresponding clause of the original Constitution as counted only three-fifths of such persons [slaves]".

- It was intended to penalize, by means of reduced Congressional representation, states that withheld the franchise from adult male citizens for any reason other than participation in crime. This, it was hoped, would induce the former slave states to recognize the political rights of the former slaves, without directly forcing them to do so—something that it was thought the states would not accept.

Enforcement

The first reapportionment after the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment occurred in 1873, based on the 1870 census. Congress appears to have attempted to enforce the provisions of Section 2, but was unable to identify enough disenfranchised voters to make a difference to any state's representation. In the implementing statute, Congress added a provision stating thatshould any state, after the passage of this Act, deny or abridge the right of any of the male inhabitants of such State, being twenty-one years of age, and citizens of the United States, to vote at any election named in the amendments to the Constitution, article fourteen, section two, except for participation in rebellion or other crime, the number of Representatives apportioned in this act to such State shall be reduced in the proportion which the number of such male citizens shall have to the whole number of male citizens twenty-one years of age in such State.A nearly identical provision remains in federal law to this day.

Despite this legislation, in subsequent reapportionments, no change has ever been made to any state's Congressional representation on the basis of the Amendment. Bonfield, writing in 1960, suggested that "[t]he hot political nature of such proposals has doomed them to failure". Aided by this lack of enforcement, southern states continued to use pretexts to prevent many blacks from voting until the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In the Fourth Circuit case of Saunders v Wilkins (1945), Saunders claimed that Virginia should have its Congressional representation reduced because of its use of a poll tax and other voting restrictions. The plaintiff sued for the right to run for Congress at large in the state, rather than in one of its designated Congressional districts. The lawsuit was dismissed as a political question.

Influence

Some have argued that Section 2 was implicitly repealed by the Fifteenth Amendment, but the Supreme Court acknowledged the provisions of Section 2 in some later decisions. In Minor v. Happersett (1875), the Supreme Court cited Section 2 as supporting its conclusion that the right to vote was not among the "privileges and immunities of citizenship" protected by Section 1. In Richardson v. Ramirez (1974), the Court cited Section 2 as justifying the states disenfranchising felons. In Hunter v. Underwood (1985), a case involving disenfranchising black misdemeanants, the Supreme Court concluded that the Tenth Amendment cannot save legislation prohibited by the subsequently enacted Fourteenth Amendment. More specifically the Court concluded that laws passed with a discriminatory purpose are not excepted from the operation of the Equal Protection Clause by the "other crime" provision of Section 2. The Court held that Section 2 "was not designed to permit the purposeful racial discrimination [...] which otherwise violates [Section] 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment."Criticism

Abolitionist leaders criticized the amendment's failure to specifically prohibit the states from denying people the right to vote on the basis of race.Section 2 protects the right to vote only of adult males, not adult females, making it the only provision of the Constitution to explicitly discriminate on the basis of sex. Section 2 was condemned by women's suffragists, such as Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, who had long seen their cause as linked to that of black rights. The separation of black civil rights from women's civil rights split the two movements for decades.

Participants in rebellion

Section 3 prohibits the election or appointment to any federal or state office of any person who had held any of certain offices and then engaged in insurrection, rebellion, or treason. However, a two-thirds vote by each House of the Congress can override this limitation. In 1898, the Congress enacted a general removal of Section 3's limitation. In 1975, the citizenship of Confederate general Robert E. Lee was restored by a joint congressional resolution, retroactive to June 13, 1865. In 1978, pursuant to Section 3, the Congress posthumously removed the service ban from Confederate president Jefferson Davis.Section 3 was used to prevent Socialist Party of America member Victor L. Berger, convicted of violating the Espionage Act for his anti-militarist views, from taking his seat in the House of Representatives in 1919 and 1920.

Validity of public debt

Section 4 confirmed the legitimacy of all public debt appropriated by the Congress. It also confirmed that neither the United States nor any state would pay for the loss of slaves or debts that had been incurred by the Confederacy. For example, during the Civil War several British and French banks had lent large sums of money to the Confederacy to support its war against the Union. In Perry v. United States (1935), the Supreme Court ruled that under Section 4 voiding a United States bond "went beyond the congressional power."The debt-ceiling crises of 2011 and 2013 raised the question of what is the President's authority under Section 4. Some, such as legal scholar Garrett Epps, fiscal expert Bruce Bartlett and Treasury Secretary Timothy Geithner, have argued that a debt ceiling may be unconstitutional and therefore void as long as it interferes with the duty of the government to pay interest on outstanding bonds and to make payments owed to pensioners (that is, Social Security and Railroad Retirement Act recipients). Legal analyst Jeffrey Rosen has argued that Section 4 gives the President unilateral authority to raise or ignore the national debt ceiling, and that if challenged the Supreme Court would likely rule in favor of expanded executive power or dismiss the case altogether for lack of standing. Erwin Chemerinsky, professor and dean at University of California, Irvine School of Law, has argued that not even in a "dire financial emergency" could the President raise the debt ceiling as "there is no reasonable way to interpret the Constitution that [allows him to do so]". Jack Balkin, Knight Professor of Constitutional Law at Yale University, opined that like Congress the President is bound by the Fourteenth Amendment, for otherwise, he could violate any part of the amendment at will. Because the President must obey the Section 4 requirement not to put the validity of the public debt into question, Balkin argued that President Obama is obliged "to prioritize incoming revenues to pay the public debt: interest on government bonds and any other 'vested' obligations. What falls into the latter category is not entirely clear, but a large number of other government obligations—and certainly payments for future services—would not count and would have to be sacrificed. This might include, for example, Social Security payments."

Power of enforcement

Section 5, also known as the Enforcement Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, enables Congress to pass laws enforcing the amendment's other provisions. In the Civil Rights Cases (1883), the Supreme Court interpreted Section 5 narrowly, stating that "the legislation which Congress is authorized to adopt in this behalf is not general legislation upon the rights of the citizen, but corrective legislation". In other words, the amendment authorizes Congress to pass laws only to combat violations of the rights protected in other sections.In Katzenbach v. Morgan (1966), the Court upheld Section 4(e) of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibits certain forms of literacy requirements as a condition to vote, as a valid exercise of Congressional power under Section 5 to enforce the Equal Protection Clause. The Court ruled that Section 5 enabled Congress to act both remedially and prophylactically to protect the rights guaranteed by the amendment. However, in City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), the Court narrowed Congress's enforcement power, holding that Congress may not enact legislation under Section 5 that substantively defines or interprets Fourteenth Amendment rights. The Court ruled that legislation is valid under Section 5 only if there is a "congruence and proportionality" between the injury to a person's Fourteenth Amendment right and the means Congress adopted to prevent or remedy that injury.