Alexis Charles Henri Clérel, Viscount de Tocqueville was a French diplomat, political scientist and historian. He was best known for his works Democracy in America (appearing in two volumes, 1835 and 1840) and The Old Regime and the Revolution (1856). In both, he analyzed the improved living standards and social conditions of individuals as well as their relationship to the market and state in Western societies. Democracy in America was published after Tocqueville's travels in the United States and is today considered an early work of sociology and political science.

Tocqueville was active in French politics, first under the July Monarchy (1830–1848) and then during the Second Republic (1849–1851) which succeeded the February 1848 Revolution. He retired from political life after Louis Napoléon Bonaparte's 2 December 1851 coup and thereafter began work on The Old Regime and the Revolution.

He argued the importance of the French Revolution was to continue the process of modernizing and centralizing the French state which had begun under King Louis XIV. The failure of the Revolution came from the inexperience of the deputies who were too wedded to abstract Enlightenment ideals. Tocqueville was a classical liberal who advocated parliamentary government, but he was skeptical of the extremes of democracy.

Life

Alexis

de Tocqueville came from an old Norman aristocratic family. His

parents, Hervé Louis François Jean Bonaventure Clérel, Count of

Tocqueville, an officer of the Constitutional Guard of King Louis XVI; and Louise Madeleine Le Peletier de Rosanbo narrowly escaped the guillotine due to the fall of Robespierre in 1794.

Under the Bourbon Restoration, Tocqueville's father became a noble peer and prefect. Tocqueville attended the Lycée Fabert in Metz.

The Fabert School in Metz, where Tocqueville was a student between 1817 and 1823

Tocqueville, who despised the July Monarchy (1830–1848), began his political career in 1839. From 1839 to 1851, he served as deputy of the Manche department (Valognes). In parliament, he sat on the centre-left, defended abolitionist views and upheld free trade while supporting the colonisation of Algeria carried on by Louis-Philippe's regime. In 1847, he sought to found a Young Left (Jeune Gauche) party which would advocate wage increases, a progressive tax, and other labor concerns in order to undermine the appeal of the socialists. Tocqueville was also elected general counsellor of the Manche in 1842 and became the president of the department's conseil général

between 1849 and 1851. According to one account, Tocqueville's

political position became untenable during this time in the sense that

he was mistrusted by both the left and right and was looking for an

excuse to leave France.

Travels

In

1831, he obtained from the July Monarchy a mission to examine prisons

and penitentiaries in the United States and proceeded there with his

lifelong friend Gustave de Beaumont.

While Tocqueville did visit some prisons, he traveled widely in the

United States and took extensive notes about his observations and

reflections. He returned within nine months and published a report, but the real result of his tour was De la démocratie en Amerique, which appeared in 1835. Beaumont also wrote an account of their travels in Jacksonian America: Marie or Slavery in the United States (1835). During this trip, he made a side trip to Lower Canada to Montreal and Quebec City from mid-August to early September 1831.

Apart from North America, Tocqueville also made an observational tour of England, producing Memoir on Pauperism. In 1841 and 1846, he traveled to Algeria. His first travel inspired his Travail sur l'Algérie in which he criticized the French model of colonisation, which was based on an assimilationist view, preferring instead the British model of indirect rule, which avoided mixing different populations together. He went as far as openly advocating racial segregation between the European colonists and the Arabs through the implementation of two different legislative systems (a half century before implementation of the 1881 Indigenous code based on religion).

In 1835, Tocqueville made a journey through Ireland. His

observations provide one of the best pictures of how Ireland stood

before the Great Famine

(1845–1849). The observations chronicle the growing Catholic middle

class and the appalling conditions in which most Catholic tenant farmers

lived. Tocqueville made clear both his libertarian sympathies and his

affinity for his Irish co-religionists.

After the fall of the July Monarchy during the February 1848 Revolution,

Tocqueville was elected a member of the Constituent Assembly of 1848,

where he became a member of the Commission charged with the drafting of

the new Constitution of the Second Republic (1848–1851). He defended bicameralism (the wisdom of two parliamentary chambers) and the election of the President of the Republic by universal suffrage.

As the countryside was thought to be more conservative than the

labouring population of Paris, universal suffrage was conceived as a

means to counteract the revolutionary spirit of Paris.

During the Second Republic, Tocqueville sided with the parti de l'Ordre

against the socialists. A few days after the February insurrection, he

believed that a violent clash between the Parisian workers' population

led by socialists agitating in favor of a "Democratic and Social

Republic" and the conservatives, which included the aristocracy and the

rural population, was inescapable. As Tocqueville had foreseen, these

social tensions eventually exploded during the June Days Uprising of 1848.

Led by General Cavaignac, the suppression was supported by Tocqueville, who advocated the "regularization" of the state of siege declared by Cavaignac and other measures promoting suspension of the constitutional order.

Between May and September, Tocqueville participated in the

Constitutional Commission which wrote the new Constitution. His

proposals underlined the importance of his North American experience as

his amendment about the President and his reelection.

Minister of foreign affairs

Caricature by Honoré Daumier, 1849

Tocqueville at the 1851 "Commission de la révision de la Constitution à l'Assemblée nationale"

A supporter of Cavaignac and of the parti de l'Ordre, Tocqueville accepted an invitation to enter Odilon Barrot's government as Minister of Foreign Affairs from 3 June to 31 October 1849. During the troubled days of June 1849, he pleaded with Interior Minister Jules Dufaure

for the reestablishment of the state of siege in the capital and

approved the arrest of demonstrators. Tocqueville, who since February

1848 had supported laws restricting political freedoms, approved the two

laws voted immediately after the June 1849 days which restricted the

liberty of clubs and freedom of the press.

This active support in favor of laws restricting political freedoms stands in contrast of his defense of freedoms in Democracy in America. According to Tocqueville, he favored order as "the sine qua non

for the conduct of serious politics. He [hoped] to bring the kind of

stability to French political life that would permit the steady growth

of liberty unimpeded by the regular rumblings of the earthquakes of

revolutionary change″.

Tocqueville had supported Cavaignac against Louis Napoléon Bonaparte

for the presidential election of 1848. Opposed to Louis Napoléon

Bonaparte's 2 December 1851 coup which followed his election,

Tocqueville was among the deputies who gathered at the 10th arrondissement

of Paris in an attempt to resist the coup and have Napoleon III judged

for "high treason" as he had violated the constitutional limit on terms

of office. Detained at Vincennes and then released, Tocqueville, who supported the Restoration of the Bourbons against Napoleon III's Second Empire (1851–1871), quit political life and retreated to his castle (Château de Tocqueville).

Against this image of Tocqueville, biographer Joseph Epstein has

concluded: "Tocqueville could never bring himself to serve a man he

considered a usurper and despot. He fought as best he could for the

political liberty in which he so ardently believed—had given it, in all,

thirteen years of his life [....]. He would spend the days remaining to

him fighting the same fight, but conducting it now from libraries,

archives, and his own desk". There, he began the draft of L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution, publishing the first tome in 1856, but leaving the second one unfinished.

Death

A longtime sufferer from bouts of tuberculosis, Tocqueville would eventually succumb to the disease on 16 April 1859 and was buried in the Tocqueville cemetery in Normandy.

Tocqueville's professed religion was Roman Catholicism.

He saw religion as being compatible with both equality and

individualism, but felt that religion would be strongest when separated

from politics.

Democracy in America

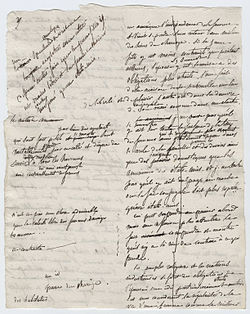

A page from original working manuscript of Democracy in America, c. 1840

In Democracy in America, published in 1835, Tocqueville wrote of the New World

and its burgeoning democratic order. Observing from the perspective of a

detached social scientist, Tocqueville wrote of his travels through the

United States in the early 19th century when the Market Revolution, Western expansion and Jacksonian democracy were radically transforming the fabric of American life.

According to Joshua Kaplan, one purpose of writing Democracy in America was to help the people of France get a better understanding of their position between a fading aristocratic order and an emerging democratic order and to help them sort out the confusion. Tocqueville saw democracy as an equation that balanced liberty and equality, concern for the individual as well as for the community.

Tocqueville was an ardent supporter of liberty. "I have a

passionate love for liberty, law, and respect for rights", he wrote. "I

am neither of the revolutionary party nor of the conservative. [...]

Liberty is my foremost passion". He wrote of "Political Consequences of

the Social State of the Anglo-Americans" by saying: "But one also finds

in the human heart a depraved taste for equality, which impels the weak

to want to bring the strong down to their level, and which reduces men

to preferring equality in servitude to inequality in freedom".

The above is often misquoted as a slavery quote because of

previous translations of the French text. The most recent translation

from Arthur Goldhammer in 2004 translates the meaning to be as stated

above. Examples of misquoted sources are numerous on the internet, but the text does not contain the words "Americans were so enamored by equality" anywhere.

His view on government reflects his belief in liberty and the

need for individuals to be able to act freely while respecting others'

rights. Of centralized government, he wrote that it "excels in

preventing, not doing".

He continues to comment on equality by saying: "Furthermore, when

citizens are all almost equal, it becomes difficult for them to defend

their independence against the aggressions of power. As none of them is

strong enough to fight alone with advantage, the only guarantee of

liberty is for everyone to combine forces. But such a combination is not

always in evidence".

Tocqueville explicitly cites inequality as being incentive for

poor to become rich and notes that it is not often that two generations

within a family maintain success and that it is inheritance laws

that split and eventually break apart someone's estate that cause a

constant cycle of churn between the poor and rich, thereby over

generations making the poor rich and rich poor. He cites protective laws

in France at the time that protected an estate from being split apart

among heirs, thereby preserving wealth and preventing a churn of wealth

such as was perceived by him in 1835 within the United States.

On civil and political society and the individual

Tocqueville's

main purpose was to analyze the functioning of political society and

various forms of political associations, although he brought some

reflections on civil society too (and relations between political and

civil society). For Tocqueville, as for Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Karl Marx, civil society was a sphere of private entrepreneurship and civilian affairs regulated by civil code. As a critic of individualism,

Tocqueville thought that through associating the coming together of

people for mutual purpose, both in public and private, Americans are

able to overcome selfish desires, thus making both a self-conscious and

active political society and a vibrant civil society functioning according to political and civil laws of the state.

According to political scientist

Joshua Kaplan, Tocqueville did not originate the concept of

individualism, instead he changed its meaning and saw it as a "calm and

considered feeling which deposes each citizen to isolate himself from

the mass of his fellows and to withdraw into the circle of family and

friends [...]. [W]ith this little society formed to his taste, he gladly

leaves the greater society to look for itself". While Tocqueville saw egotism and selfishness

as vices, he saw individualism as not a failure of feeling, but as a

way of thinking about things which could have either positive

consequences such as a willingness to work together, or negative

consequences such as isolation and that individualism could be remedied

by improved understanding.

When individualism was a positive force and prompted people to

work together for common purposes and seen as "self-interest properly

understood", then it helped to counterbalance the danger of the tyranny of the majority since people could "take control over their own lives" without government aid.

According to Kaplan, Americans have a difficult time accepting

Tocqueville's criticism of the stifling intellectual effect of the

"omnipotence of the majority" and that Americans tend to deny that there

is a problem in this regard.

Others, such as the Catholic writer Daniel Schwindt,

disagree with Kaplan's interpretation, arguing instead that Tocqueville

saw individualism as just another form of egotism and not an

improvement over it. To make his case, Schwindt provides citations such as the following:

Egoism springs from a blind instinct; individualism from wrong-headed thinking rather than from depraved feelings. It originates as much from defects of intelligence as from the mistakes of the heart. Egoism blights the seeds of every virtue; individualism at first dries up only the source of public virtue. In the longer term it attacks and destroys all the others and will finally merge with egoism.

On democracy and new forms of tyranny

Tocqueville

warned that modern democracy may be adept at inventing new forms of

tyranny because radical equality could lead to the materialism of an

expanding bourgeoisie and to the selfishness of individualism. "In such

conditions, we might become so enamored with 'a relaxed love of present

enjoyments' that we lose interest in the future of our descendants...and

meekly allow ourselves to be led in ignorance by a despotic force all

the more powerful because it does not resemble one", wrote The New Yorker's James Wood. Tocqueville worried that if despotism

were to take root in a modern democracy, it would be a much more

dangerous version than the oppression under the Roman emperors or

tyrants of the past who could only exert a pernicious influence on a

small group of people at a time.

In contrast, a despotism under a democracy could see "a multitude

of men", uniformly alike, equal, "constantly circling for petty

pleasures", unaware of fellow citizens and subject to the will of a

powerful state which exerted an "immense protective power".

Tocqueville compared a potentially despotic democratic government to a

protective parent who wants to keep its citizens (children) as

"perpetual children" and which does not break men's wills, but rather

guides it and presides over people in the same way as a shepherd looking

after a "flock of timid animals".

On American social contract

Tocqueville's

penetrating analysis sought to understand the peculiar nature of

American political life. In describing the American, he agreed with

thinkers such as Aristotle and Montesquieu that the balance of property

determined the balance of political power, but his conclusions after

that differed radically from those of his predecessors. Tocqueville

tried to understand why the United States was so different from Europe

in the last throes of aristocracy.

In contrast to the aristocratic ethic, the United States was a society

where hard work and money-making was the dominant ethic, where the

common man enjoyed a level of dignity which was unprecedented, where

commoners never deferred to elites and where what he described as crass

individualism and market capitalism had taken root to an extraordinary

degree.

Tocqueville writes: "Among a democratic people, where there is no

hereditary wealth, every man works to earn a living. [...] Labor is

held in honor; the prejudice is not against but in its favor".

A sketch of Tocqueville

Tocqueville asserted that the values that had triumphed in the North

and were present in the South had begun to suffocate old-world ethics

and social arrangements. Legislatures abolished primogeniture and entails,

resulting in more widely distributed land holdings. This was a contrast

to the general aristocratic pattern in which only the eldest child,

usually a man, inherited the estate, which had the effect of keeping

large estates intact from generation to generation.

In contrast, in the United States landed elites were less likely to pass on fortunes to a single child by the action of primogeniture,

which meant that as time went by large estates became broken up within a

few generations which in turn made the children more equal overall.

According to Joshua Kaplan's interpretation of Tocqueville, it was not

always a negative development since bonds of affection and shared

experience between children often replaced the more formal relation

between the eldest child and the siblings, characteristic of the

previous aristocratic pattern.

Overall, in the new democracies hereditary fortunes became exceedingly

difficult to secure and more people were forced to struggle for their

own living.

As Tocqueville understood it, this rapidly democratizing society

had a population devoted to "middling" values which wanted to amass

through hard work vast fortunes. In Tocqueville's mind, this explained

why the United States was so different from Europe. In Europe, he

claimed, nobody cared about making money. The lower classes had no hope

of gaining more than minimal wealth while the upper classes found it

crass, vulgar and unbecoming of their sort to care about something as

unseemly as money and many were virtually guaranteed wealth and took it

for granted. At the same time in the United States, workers would see

people fashioned in exquisite attire and merely proclaim that through

hard work they too would soon possess the fortune necessary to enjoy

such luxuries.

Despite maintaining that the balance of property determined the

balance of power, Tocqueville argued that as the United States showed,

equitable property holdings did not ensure the rule of the best men. In

fact, it did quite the opposite as the widespread, relatively equitable

property ownership which distinguished the United States and determined

its mores and values also explained why the United States masses held

elites in such contempt.

On majority rule and mediocrity

Beyond

the eradication of old-world aristocracy, ordinary Americans also

refused to defer to those possessing, as Tocqueville put it, superior

talent and intelligence and these natural elites could not enjoy much

share in political power as a result. Ordinary Americans enjoyed too

much power and claimed too great a voice in the public sphere to defer

to intellectual superiors. This culture promoted a relatively pronounced

equality, Tocqueville argued, but the same mores and opinions that

ensured such equality also promoted mediocrity. Those who possessed true

virtue and talent were left with limited choices.

Tocqueville said that those with the most education and

intelligence were left with two choices. They could join limited

intellectual circles to explore the weighty and complex problems facing

society, or they could use their superior talents to amass vast fortunes

in the private sector. Tocqueville wrote that he did not know of any

country where there was "less independence of mind, and true freedom of

discussion, than in America".

He blamed the omnipotence of majority rule

as a chief factor in stifling thinking: "The majority has enclosed

thought within a formidable fence. A writer is free inside that area,

but woe to the man who goes beyond it, not that he stands in fear of an

inquisition, but he must face all kinds of unpleasantness in every day

persecution. A career in politics is closed to him for he has offended

the only power that holds the keys".

In contrast to previous political thinkers, Tocqueville argued that a

serious problem in political life was not that people were too strong,

but that people were "too weak" and felt powerless as the danger is that

people felt "swept up in something that they could not control",

according to Kaplan's interpretation of Tocqueville.

On slavery, blacks and Indians

Uniquely positioned at a crossroads in American history, Tocqueville's Democracy in America

attempted to capture the essence of American culture and values. Though

a supporter of colonialism, Tocqueville could clearly perceive the

evils that black people and natives had been subjected to in the United

States. Tocqueville devoted the last chapter of the first volume of Democracy in America

to the question while his travel companion Gustave de Beaumont wholly

focused on slavery and its fallouts for the American nation in Marie or Slavery in America. Tocqueville notes among the American races:

The first who attracts the eye, the first in enlightenment, in power and in happiness, is the white man, the European, man par excellence; below him appear the Negro and the Indian. These two unfortunate races have neither birth, nor face, nor language, nor mores in common; only their misfortunes look alike. Both occupy an equally inferior position in the country that they inhabit; both experience the effects of tyranny; and if their miseries are different, they can accuse the same author for them.

Tocqueville contrasted the settlers of Virginia with the middle class, religious Puritans who founded New England and analyzed the debasing influence of slavery:

The men sent to Virginia were seekers of gold, adventurers without resources and without character, whose turbulent and restless spirit endangered the infant colony. [...] Artisans and agriculturalists arrived afterwards[,] [...] hardly in any respect above the level of the inferior classes in England. No lofty views, no spiritual conception presided over the foundation of these new settlements. The colony was scarcely established when slavery was introduced; this was the capital fact which was to exercise an immense influence on the character, the laws and the whole future of the South. Slavery [...] dishonors labor; it introduces idleness into society, and with idleness, ignorance and pride, luxury and distress. It enervates the powers of the mind and benumbs the activity of man. On this same English foundation there developed in the North very different characteristics.

Tocqueville concluded that return of the Negro population to Africa could not resolve the problem as he writes at the end of Democracy in America:

If the colony of Liberia were able to receive thousands of new inhabitants every year, and if the Negroes were in a state to be sent thither with advantage; if the Union were to supply the society with annual subsidies, and to transport the Negroes to Africa in government vessels, it would still be unable to counterpoise the natural increase of population among the blacks; and as it could not remove as many men in a year as are born upon its territory within that time, it could not prevent the growth of the evil which is daily increasing in the states. The Negro race will never leave those shores of the American continent to which it was brought by the passions and the vices of Europeans; and it will not disappear from the New World as long as it continues to exist. The inhabitants of the United States may retard the calamities which they apprehend, but they cannot now destroy their efficient cause.

In 1855, he wrote the following text published by Maria Weston Chapman in the Liberty Bell: Testimony against Slavery:

I do not think it is for me, a foreigner, to indicate to the United States the time, the measures, or the men by whom Slavery shall be abolished. Still, as the persevering enemy of despotism everywhere, and under all its forms, I am pained and astonished by the fact that the freest people in the world is, at the present time, almost the only one among civilized and Christian nations which yet maintains personal servitude; and this while serfdom itself is about disappearing, where it has not already disappeared, from the most degraded nations of Europe.

An old and sincere friend of America, I am uneasy at seeing Slavery retard her progress, tarnish her glory, furnish arms to her detractors, compromise the future career of the Union which is the guaranty of her safety and greatness, and point out beforehand to her, to all her enemies, the spot where they are to strike. As a man, too, I am moved at the spectacle of man's degradation by man, and I hope to see the day when the law will grant equal civil liberty to all the inhabitants of the same empire, as God accords the freedom of the will, without distinction, to the dwellers upon earth.

On policies of assimilation

According

to Tocqueville, assimilation of black people would be almost impossible

and this was already being demonstrated in the Northern states. As

Tocqueville predicted, formal freedom and equality and segregation would

become this population's reality after the Civil War and during Reconstruction as would the bumpy road to true integration of black people.

However, assimilation was the best solution for Native Americans

and since they were too proud to assimilate, they would inevitably

become extinct. Displacement was another part of America's Indian policy.

Both populations were "undemocratic", or without the qualities,

intellectual and otherwise needed to live in a democracy. Tocqueville

shared many views on assimilation and segregation of his and the coming

epochs, but he opposed Arthur de Gobineau's theories as found in The Inequality of Human Races (1853–1855).

On the United States and Russia as future global powers

In his Democracy in America,

Tocqueville also forecast the preeminence of the United States and

Russia as the two main global powers. In his book, he stated: "There are

now two great nations in the world, which starting from different

points, seem to be advancing toward the same goal: the Russians and the

Anglo-Americans... Each seems called by some secret design of Providence

one day to hold in its hands the destinies of half the world".

On civil jury service

Tocqueville

believed that the American jury system was particularly important in

educating citizens in self-government and rule of law.

He often expressed how the civil jury system was one of the most

effective showcases of democracy because it connected citizens with the

true spirit of the justice system. In his 1835 treatise Democracy in America,

he explained: "The jury, and more especially the civil jury, serves to

communicate the spirit of the judges to the minds of all the citizens;

and this spirit, with the habits which attend it, is the soundest

preparation for free institutions. [...] It invests each citizen with a

kind of magistracy; it makes them all feel the duties which they are

bound to discharge toward society; and the part which they take in the

Government".

Tocqueville believed that jury service not only benefited the

society as a whole, but enhanced jurors' qualities as citizens. Because

of the jury system, "they were better informed about the rule of law,

and they were more closely connected to the state. Thus, quite

independently of what the jury contributed to dispute resolution,

participation on the jury had salutary effects on the jurors

themselves".

1841 discourse on the Conquest of Algeria

French historian of colonialism Olivier LeCour Grandmaison has underlined how Tocqueville (as well as Jules Michelet) used the term "extermination" to describe what was happening during the colonization of Western United States and the Indian removal period. Tocqueville thus expressed himself in 1841 concerning the conquest of Algeria:

As far as I am concerned, I came back from Africa with the pathetic notion that at present in our way of waging war we are far more barbaric than the Arabs themselves. These days, they represent civilization, we do not. This way of waging war seems to me as stupid as it is cruel. It can only be found in the head of a coarse and brutal soldier. Indeed, it was pointless to replace the Turks only to reproduce what the world rightly found so hateful in them. This, even for the sake of interest is more noxious than useful; for, as another officer was telling me, if our sole aim is to equal the Turks, in fact we shall be in a far lower position than theirs: barbarians for barbarians, the Turks will always outdo us because they are Muslim barbarians. In France, I have often heard men I respect but do not approve of, deplore that crops should be burnt and granaries emptied and finally that unarmed men, women, and children should be seized. In my view these are unfortunate circumstances that any people wishing to wage war against the Arabs must accept. I think that all the means available to wreck tribes must be used, barring those that the human kind and the right of nations condemn. I personally believe that the laws of war enable us to ravage the country and that we must do so either by destroying the crops at harvest time or any time by making fast forays also known as raids the aim of which it to get hold of men or flocks.

Whatever the case, we may say in a general manner that all political freedoms must be suspended in Algeria.

Tocqueville thought the conquest of Algeria was important for two

reasons: first, his understanding of the international situation and

France's position in the world; and second, changes in French society.

Tocqueville believed that war and colonization would "restore national

pride, threatened", he believed, by "the gradual softening of social

mores" in the middle classes. Their taste for "material pleasures" was

spreading to the whole of society, giving it "an example of weakness and

egotism".

Applauding the methods of General Bugeaud,

Tocqueville went so far to claim that "war in Africa is a science.

Everyone is familiar with its rules and everyone can apply those rules

with almost complete certainty of success. One of the greatest services

that Field Marshal Bugeaud has rendered his country is to have spread,

perfected and made everyone aware of this new science".

Tocqueville advocated racial segregation in Algeria with two distinct legislations, one for European colonists and one for the Arab population. Such a two-tier arrangement would be fully realised with the 1870 Crémieux decree and the Indigenousness Code, which extended French citizenship

to European settlers and Algerian Jews whereas Muslim Algerians would

be governed by Muslim law and restricted to a second-class citizenship.

Tocqueville's opposition to the invasion of Kabylie

In

opposition to Olivier Le Cour Grandmaison, Jean-Louis Benoît claimed

that given the extent of racial prejudices during the colonization of

Algeria, Tocqueville was one of its "most moderate supporters". Benoît

claimed that it was wrong to assume Tocqueville was a supporter of

Bugeaud despite his 1841 apologetic discourse. It seems that Tocqueville

modified his views after his second visit to Algeria in 1846 as he

criticized Bugeaud's desire to invade Kabylie in an 1847 speech to the Assembly.

Although Tocqueville had favoured retention of distinct traditional law, administrators, schools and so on for Arabs who had come under French control, he judged the Berber tribes of Kabylie (in his second of Two Letters on Algeria,

1837) as "savages" not suited for this arrangement because he argued

they would best be managed not by force of arms, but by the pacifying

influences of commerce and cultural interaction.

Tocqueville's views on the matter were complex. Even though in

his 1841 report on Algeria he applauded Bugeaud for making war in a way

that defeated Abd-el-Kader's resistance, he had advocated in the Two Letters

that the French military advance leave Kabylie undisturbed and in

subsequent speeches and writings he continued to oppose intrusion into

Kabylie.

In the debate about the 1846 extraordinary funds, Tocqueville

denounced Bugeaud's conduct of military operations and succeeded in

convincing the Assembly not to vote funds in support of Bugeaud's

military columns.

Tocqueville considered Bugeaud's plan to invade Kabylie despite the

opposition of the Assembly as a seditious act in the face of which the

government was opting for cowardice.

1847 Report on Algeria

In his 1847 Report on Algeria, Tocqueville declared that Europe should avoid making the same mistake they made with the European colonization of the Americas in order to avoid the bloody consequences.

More particularly he reminds his countrymen of a solemn caution whereby

he warns them that if the methods used towards the Algerian people

remain unchanged, colonization will end in a blood bath.

Tocqueville includes in his report on Algeria that the fate of

their soldiers and finances depended on how the French government treats

the various native populations of Algeria, including the various Arab

tribes, independent Kabyles living in the Atlas Mountains and the powerful political leader Abd-el-Kader.

In his various letters and essays on Algeria, Tocqueville discusses

contrasting strategies by which a European country can approach

imperialism. In particular, the author differentiates between what he

terms "dominance" and a particular version of "colonization".

The latter stresses the obtainment and protection of land and

passageways that promise commercial wealth. In the case of Algeria, the

Port of Algiers and the control over the Strait of Gibraltar

were considered by Tocqueville to be particularly valuable whereas

direct control of the political operations of the entirety of Algeria

was not. Thus, the author stresses domination over only certain points

of political influence as a means to colonization of commercially

valuable areas.

Tocqueville argued that though unpleasant, domination via violent

means is necessary for colonization and justified by the laws of war.

Such laws are not discussed in detail, but given that the goal of the

French mission in Algeria was to obtain commercial and military interest

as opposed to self-defense, it can be deduced that Tocqueville would

not concur with just war theory's jus ad bellum criteria of just cause.

Further, given that Tocqueville approved of the use of force to

eliminate civilian housing in enemy territory, his approach does not

accord with just war theory's jus in bello criteria of proportionality and discrimination.

The Old Regime and the Revolution

In 1856, Tocqueville published The Old Regime and the Revolution. The book analyzes French society before the French Revolution—the so-called Ancien Régime—and investigates the forces that caused the Revolution.

References in popular literature

Tocqueville was quoted in several chapters of Toby Young's memoirs How to Lose Friends and Alienate People to explain his observation of widespread homogeneity of thought even amongst intellectual elites at Harvard University

during his time spent there. He is frequently quoted and studied in

American history classes. Tocqueville is the inspiration for Australian

novelist Peter Carey in his 2009 novel Parrot and Olivier in America.

Works

- Alexis de Tocqueville and Gustave de Beaumont in America: Their Friendship and Their Travels, edited by Oliver Zunz, translated by Arthur Goldhammer (University of Virginia Press, 2011), 698 pages. Includes previously unpublished letters, essays, and other writings.

- Du système pénitentaire aux États-Unis et de son application en France (1833) – On the Penitentiary System in the United States and Its Application to France, with Gustave de Beaumont.

- De la démocratie en Amérique (1835/1840) – Democracy in America. It was published in two volumes, the first in 1835, the second in 1840. English language versions: Tocqueville, Democracy in America, trans. and eds, Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop, University of Chicago Press, 2000; Tocqueville, Democracy in America (Arthur Goldhammer, trans.; Olivier Zunz, ed.) (The Library of America, 2004) ISBN 978-1-931082-54-9.

- L'Ancien Régime et la Révolution (1856) – The Old Regime and the Revolution. It is Tocqueville's second most famous work.

- Recollections (1893) – This work was a private journal of the Revolution of 1848. He never intended to publish this during his lifetime; it was published by his wife and his friend Gustave de Beaumont after his death.

- Journey to America (1831–1832) – Alexis de Tocqueville's travel diary of his visit to America; translated into English by George Lawrence, edited by J.-P. Mayer, Yale University Press, 1960; based on vol. V, 1 of the Œuvres Complètes of Tocqueville.

- L'Etat social et politique de la France avant et depuis 1789 – Alexis de Tocqueville

- Memoir On Pauperism: Does public charity produce an idle and dependant class of society? (1835) originally published by Ivan R. Dee. Inspired by a trip to England. One of Tocqueville's more obscure works.

- Journeys to England and Ireland, 1835.