From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Osteopathic medicine is a branch of the medical profession in the United States. Osteopathic physicians (DOs) are licensed to practice medicine and surgery in all 50 states and are recognized to varying degrees in 65 other countries.

Frontier physician Andrew Taylor Still founded the profession as a rejection of the prevailing system of medical thought of the 19th century. Still's techniques relied on manipulation of joints and bones, to diagnose and treat illness, and he called his practices "osteopathy". By the middle of the 20th century, the profession had moved closer to mainstream medicine, adopting modern public health and biomedical principles. American "osteopaths" became "osteopathic medical doctors", ultimately achieving full practice rights as medical doctors in all 50 states, including serving in the United States Armed Forces as physicians and surgeons.

In modern medicine, any distinction between the MD and the DO professions has eroded steadily. Diminishing numbers of DO graduates enter primary care fields, fewer use osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT), and increasing numbers of osteopathic graduates choose to train in non-osteopathic residency programs. An osteopathic physician (DO) is a fully licensed, patient-centered physician. DO has full medical practice rights throughout the United States and in 44 countries abroad.

In the 21st century, the training of osteopathic physicians in the United States is equivalent to the training of Doctors of Medicine (MDs). Osteopathic physicians attend four years of medical school followed by an internship and a minimum two years of residency. They use all conventional methods of diagnosis and treatment. Though still trained in OMT, the modern derivative of Still's techniques, they work in all specialties of medicine. Discussions about the future of modern medicine frequently debate the utility of maintaining separate, distinct pathways for educating physicians in the United States.

Frontier physician Andrew Taylor Still founded the profession as a rejection of the prevailing system of medical thought of the 19th century. Still's techniques relied on manipulation of joints and bones, to diagnose and treat illness, and he called his practices "osteopathy". By the middle of the 20th century, the profession had moved closer to mainstream medicine, adopting modern public health and biomedical principles. American "osteopaths" became "osteopathic medical doctors", ultimately achieving full practice rights as medical doctors in all 50 states, including serving in the United States Armed Forces as physicians and surgeons.

In modern medicine, any distinction between the MD and the DO professions has eroded steadily. Diminishing numbers of DO graduates enter primary care fields, fewer use osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT), and increasing numbers of osteopathic graduates choose to train in non-osteopathic residency programs. An osteopathic physician (DO) is a fully licensed, patient-centered physician. DO has full medical practice rights throughout the United States and in 44 countries abroad.

In the 21st century, the training of osteopathic physicians in the United States is equivalent to the training of Doctors of Medicine (MDs). Osteopathic physicians attend four years of medical school followed by an internship and a minimum two years of residency. They use all conventional methods of diagnosis and treatment. Though still trained in OMT, the modern derivative of Still's techniques, they work in all specialties of medicine. Discussions about the future of modern medicine frequently debate the utility of maintaining separate, distinct pathways for educating physicians in the United States.

Nomenclature

Physicians

and surgeons who graduate from osteopathic medical schools are known as

osteopathic physicians or osteopathic medical doctors. Upon graduation, they are conferred a professional doctorate, the Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine (DO).

Osteopathic curricula in other countries differ from those in the

United States. European-trained practitioners of osteopathic

manipulative techniques are referred to as "osteopaths": their scope of

practice excludes most medical therapies and relies more on osteopathic manipulative medicine and alternative medical modalities.

While it was once common for DO graduates in the United States to refer

to themselves as "osteopaths", this term is now considered archaic, and

those holding the Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree are commonly

referred to as "osteopathic medical physicians".

Demographics

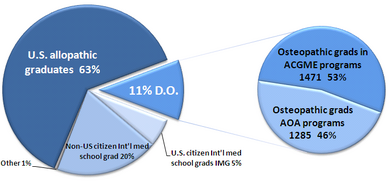

Physicians entering US workforce by education, 2005

Currently in 2018 there are 35 medical schools that offer DO Degrees in 55 locations

across the United States, while there are 141 accredited MD medical schools.

- In 1960, there were 13,708 physicians who were graduates of the 5 osteopathic medical schools.

- In 2002, there were 49,210 physicians from 19 osteopathic medical schools.

- Between 1980 and 2005, the number of osteopathic graduates per year increased over 150 percent from about 1,000 to 2,800. This number is expected to approach 5,000 by 2015.

- In 2016, there were 33 colleges of osteopathic medicine in 48 locations, in 31 states. One in four medical students in the United States is enrolled in an osteopathic medical school.

- As of 2018, there are more than 145,000 osteopathic medical physicians (DOs) and osteopathic medical students in the United States.

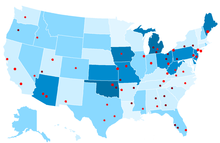

Geographic

distribution of osteopathic physicians as a percentage of all

physicians, by the state. Locations of osteopathic medical schools are

in red. <3 span=""> 3-5% 5-10% 10-15% 15-25%

Osteopathic physicians are not evenly distributed in the United States.

States with the highest concentration of osteopathic medical physicians

are Oklahoma, Iowa, and Michigan where osteopathic medical physicians comprise 17–20% of the total physician workforce. The state with the greatest number of osteopathic medical physicians is Pennsylvania, with 8,536 DOs in active practice in 2018. The states with the lowest concentrations of DOs are Washington, DC, North Dakota and Vermont where only 1–3% of physicians have an osteopathic medical degree.

Public awareness of osteopathic medicine likewise varies widely in

different regions. People living in the midwest states are the most

likely to be familiar with osteopathic medicine. In the Northeastern United States, osteopathic medical physicians provide more than one third of general and family medicine patient visits.

Between 2010 and 2015 twelve states experienced greater than 50% growth

in the number of DOs—Virginia, South Carolina, Utah, Tennessee, North

Dakota, Kentucky, South Dakota, Wyoming, Oregon, North Carolina,

Minnesota, Washington.

Osteopathic principles

A physician demonstrates an OMT technique to medical students at an osteopathic medical school.

Osteopathic medical students take the Osteopathic Oath, similar to the Hippocratic oath,

to maintain and uphold the "core principles" of osteopathic medical

philosophy. Revised in 1953, and again in 2002, the core principles are:

- The body is a unit; a person is a unit of body, mind, and spirit.

- The body is capable of self-regulation, self-healing, and health maintenance.

- Structure and function are reciprocally interrelated.

- Rational treatment is based on an understanding of these principles: body unity, self-regulation, and the interrelationship of structure and function.

Contemporary osteopathic physicians practice evidence-based medicine, indistinguishable from their MD colleagues.

Significance

There

are different opinions on the significance of these principles. Some

note that the osteopathic medical philosophy is akin to the tenets of holistic medicine, suggestive of a kind of social movement

within the field of medicine, one that promotes a more

patient-centered, holistic approach to medicine, and emphasizes the role

of the primary care physician within the health care system.

Others point out that there is nothing in the principles that would

distinguish DO from MD training in any fundamental way. One study,

published in The Journal of the American Osteopathic Association

found a majority of MD medical school administrators and faculty saw

nothing objectionable in the core principles listed above, and some

endorse them generally as broad medical principles.

History

19th century, a new movement within medicine

Andrew Taylor Still, founder of osteopathic medicine

Frontier physician Andrew Taylor Still, MD, DO, founded the American School of Osteopathy (now the A.T. Still University-Kirksville (Mo.) College of Osteopathic Medicine) in Kirksville, Missouri

in 1892 as a radical protest against the turn-of-the-century medical

system. A.T. Still believed that the conventional medical system lacked

credible efficacy, was morally corrupt, and treated effects rather than

causes of disease.

He founded osteopathic medicine in rural Missouri at a time when

medications, surgery, and other traditional therapeutic regimens often

caused more harm than good. Some of the medicines commonly given to

patients during this time were arsenic, castor oil, whiskey, and opium. In addition, unsanitary surgical practices often resulted in more deaths than cures.

"To find health should be the object of the doctor.Andrew Taylor Still, 1874

Anyone can find disease."

Dr. Still intended his new system of medicine to be a reformation of

the existing 19th-century medical practices. He imagined that someday

"rational medical therapy" would consist of manipulation of the

musculoskeletal system, surgery, and very sparingly used drugs. He

invented the name "osteopathy" by blending two Greek roots osteon- for bone and -pathos for suffering in order to communicate his theory that disease and physiologic dysfunction were etiologically

grounded in a disordered musculoskeletal system. Thus, by diagnosing

and treating the musculoskeletal system, he believed that physicians

could treat a variety of diseases and spare patients the negative

side-effects of drugs.

Mark Twain was a vocal supporter of the early osteopathic movement.

The

new profession faced stiff opposition from the medical establishment at

the time. The relationship of the osteopathic and medical professions

was often "bitterly contentious" and involved "strong efforts" by medical organizations to discredit osteopathic medicine. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, the policy of the American Medical Association labeled osteopathic medicine as a cult. The AMA code of ethics declared it unethical for a medical physician to voluntarily associate with an osteopath.

"To ask a doctor's opinion of osteopathy is equivalent to going to Satan for information about Christianity."Mark Twain, 1901

One notable advocate for the fledgling movement was Mark Twain. Manipulative treatments had purportedly alleviated the symptoms of his daughter Jean's epilepsy as well as Twain's own chronic bronchitis. In 1909, he spoke before the New York State Assembly

at a hearing regarding the practice of osteopathy in the state." I

don't know as I cared much about these osteopaths until I heard you were

going to drive them out of the state, but since I heard that I haven't

been able to sleep." Philosophically opposed to the American Medical

Association's stance that its own type of medical practice was the only

legitimate one, he spoke in favor of licensing for osteopaths.

Physicians from the New York County Medical Society

responded with a vigorous attack on Twain, who retorted with "[t]he

physicians think they are moved by regard for the best interests of the

public. Isn't there a little touch of self-interest back of it all?"

"... The objection is, people are curing people without a license and

you are afraid it will bust up business."

| Evolution of osteopathic medicine's mission and identity | ||

| Years | Identity & Mission | |

| 1892 to 1950 | Manual medicine | |

| 1951 to 1970 | Family practice / manual therapy | |

| 1971 to present | Full service care / multispeciality orientation | |

1916–1966, federal recognition

Recognition by the US federal government

was a key goal of the osteopathic medical profession in its effort to

establish equivalency with its MD counterparts. Between 1916 and 1966,

the profession engaged in a "long and tortuous struggle" for the right

to serve as physicians and surgeons in the US Military Medical Corps. On May 3, 1966 Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara

authorized the acceptance of osteopathic physicians into all the

medical military services on the same basis as MDs. The first

osteopathic physician to take the oath of office to serve as a military

physician was Harry J. Walter. The acceptance of osteopathic physicians was further solidified in 1996 when Ronald Blanck, DO was appointed to serve as Surgeon General of the Army, the only osteopathic physician to hold the post.

1962, California

In the 1960s in California, the American Medical Association (AMA) spent nearly $8 million

to end the practice of osteopathic medicine in the state. In 1962,

Proposition 22, a statewide ballot initiative in California, eliminated

the practice of osteopathic medicine in the state. The California

Medical Association (CMA) issued MD degrees to all DOs

in the state of California for a nominal fee. "By attending a short

seminar and paying $65, a doctor of osteopathy (DO) could obtain an MD

degree; 86 percent of the DOs in the state (out of a total of about

2000) chose to do so." Immediately following, the AMA re-accredited the University of California at Irvine College of Osteopathic Medicine as the University of California, Irvine School of Medicine, an MD medical school. It also placed a ban on issuing physician licenses to DOs moving to California from other states. However, the decision proved to be controversial. In 1974, after protests and lobbying by influential and prominent DOs, the California Supreme Court ruled in Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons of California v. California Medical Association, that licensing of DOs in that state must be resumed. Four years later, in 1978, the College of Osteopathic Medicine of the Pacific opened in Pomona, and in 1997, Touro University California opened in Vallejo. As of 2012, there were 6,368 DOs practicing in California.

1969, AMA House of Delegates approval

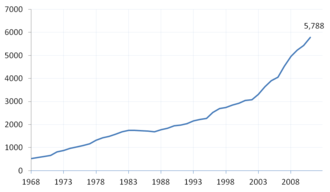

Total number of DOs in residency programs, by year.

DO residents in ACGME (MD) programs

DO residents in AOA (DO) programs.

In 1969, the American Medical Association (AMA) approved a measure

allowing qualified osteopathic physicians to be full and active members

of the Association. The measure also allowed osteopathic physicians to

participate in AMA-approved intern and residency programs. However, the American Osteopathic Association

rejected this measure, claiming it was an attempt to eliminate the

distinctiveness of osteopathic medicine. In 1970, AMA President Dwight

L. Wilbur sponsored a measure in the AMA's House of Delegates permitting

the AMA Board of Trustees' plan for the merger of DO and MD

professions. Today, a majority of osteopathic physicians are trained

alongside MDs, in residency programs governed by the ACGME, an independent board of the AMA.

1993, first African-American woman to serve as dean of a US medical school

In 1993, Barbara Ross-Lee, DO, was appointed to the position of dean of the Ohio University College of Osteopathic Medicine; she was the first African-American woman to serve as the dean of a US medical school. Ross-Lee now is the dean of the NYIT College of Osteopathic Medicine at Arkansas State University in Jonesboro, Arkansas.

Non-discrimination policies

Recent

years have seen a professional rapprochement between the two groups.

DOs have been admitted to full active membership in the American Medical

Association since 1969. The AMA has invited a representative of the

American Osteopathic Association to sit as a voting member in the AMA

legislative body, the house of delegates.

2006, American Medical Student Association

In 2006, during the presidency of an osteopathic medical student, the American Medical Student Association

(AMSA) adopted a policy regarding the membership rights of osteopathic

medical students in their main policy document, the "Preamble, Purposes

and Principles."

AMSA RECOGNIZES the equality of osteopathic and allopathic medical degrees within the organization and the healthcare community as a whole. As such, DO students shall be entitled to the same opportunities and membership rights as allopathic students.

— PPP, AMSA

2007, AMA

In

recent years, the largest MD organization in the US, the American

Medical Association, adopted a fee non-discrimination policy

discouraging differential pricing based on attendance of an MD or DO

medical school.

In 2006, calls for an investigation into the existence of

differential fees charged for visiting DO and MD medical students at

American medical schools were brought to the American Medical

Association. After an internal investigation into the fee structure for

visiting DO and MD medical students at MD medical schools, it was found

that one institution of the 102 surveyed charged different fees for DO

and MD students. The house of delegates of the American Medical Association adopted resolution 809, I-05 in 2007.

Our AMA, in collaboration with the American Osteopathic Association, discourages discrimination against medical students by institutions and programs based on osteopathic or allopathic training.

— AMA policy H-295.876

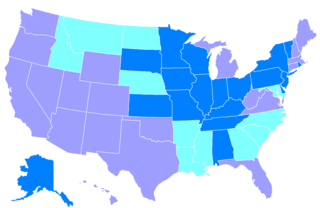

Years in which states passed laws granting DOs medical practice rights equal to MDs

1901–1930 1931–1966 1967–1989

1901–1930 1931–1966 1967–1989

State licensing of practice rights

In

the United States, laws regulating physician licenses are governed by

the states. Between 1901 and 1989, osteopathic physicians lobbied state

legislatures to pass laws giving those with a DO degree the same legal

privilege to practice medicine as those with an MD degree. In many

states, the debate was long and protracted. Both the AOA and the AMA

were heavily involved in influencing the legislative process. The first

state to pass such a law was California in 1901, the last was Nebraska in 1989.

Current status

Education and training

According to Harrison's Principles of Internal Medicine,

"the training, practice, credentialing, licensure, and reimbursement of

osteopathic physicians is virtually indistinguishable from those of (MD) physicians, with 4 years of osteopathic medical school followed by specialty and subspecialty training and [board] certification."

DO-granting US medical schools have curricula

similar to those of MD-granting schools. Generally, the first two years

are classroom-based, while the third and fourth years consist of clinical rotations through the major specialties of medicine.

Some schools of Osteopathic Medicine have been criticized by the

osteopathic community for relying too heavily on clinical rotations with

private practitioners, who may not be able to provide sufficient

instruction to the rotating student.

Other DO-granting and MD-granting schools place their students in

hospital-based clinical rotations where the attending physicians are

faculty of the school, and who have a clear duty to teach medical

students while treating patients.

Graduate medical education

Sources of the 24,012 medical school graduates entering US physician training programs in 2004.

Upon graduation, most osteopathic medical physicians pursue residency training programs. Depending on state licensing laws, osteopathic medical physicians may also complete a one-year rotating internship at a hospital approved by the American Osteopathic Association (AOA).

Osteopathic physicians may apply to residency programs accredited by either the AOA or the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

(ACGME). Currently, osteopathic physicians participate in more ACGME

programs than in programs approved by the American Osteopathic

Association (AOA).

By June 30, 2020, all AOA residencies will also be required to have

ACGME accreditation, and the AOA will cease accreditation activities.

Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT)

Osteopathic manipulative treatment (OMT) involves palpation and manipulation of bones, muscles, joints, and fasciae.

Within the osteopathic medical curriculum, manipulative treatment is

taught as an adjunctive measure to other biomedical interventions for a

number of disorders and diseases. However, a 2001 survey of osteopathic

physicians found that more than 50% of the respondents used OMT on less

than 5% of their patients. The survey follows many indicators that

osteopathic physicians have become more like MD physicians in every

respect —few perform OMT, and most prescribe medications or suggest

surgery as the first line of treatment.

The American Osteopathic Association

has made an effort in recent years to support scientific inquiry into

the effectiveness of osteopathic manipulation as well as to encourage

osteopathic physicians to consistently offer manipulative treatments to

their patients. However, the number of osteopathic physicians who report

consistently prescribing and performing manipulative treatment has been

falling steadily. Medical historian and sociologist Norman Gevitz

cites poor educational quarters and few full-time OMT instructors as

major factors for the decreasing interest of medical students in OMT. He

describes problems with "the quality, breadth, nature, and orientation

of OMM instruction," and he claims that the teaching of osteopathic

medicine has not changed sufficiently over the years to meet the

intellectual and practical needs of students.

In their assigned readings, students learn what certain prominent DOs have to say about various somatic dysfunctions. There is often a theory or model presented that provides conjectures and putative explanations about why somatic dysfunction exists and what its significance is. Instructors spend the bulk of their time demonstrating osteopathic manipulative (OM) techniques without providing evidence that the techniques are significant and efficacious. Even worse, faculty members rarely provide instrument-based objective evidence that somatic dysfunction is present in the first place.

At the same time, recent studies show an increasingly positive

attitude of patients and physicians (MD and DO) towards the use of

manual therapy as a valid, safe and effective treatment modality. One survey, published in the Journal of Continuing Medical Education,

found that a majority of physicians (81%) and patients (76%) felt that

manual manipulation (MM) was safe, and over half (56% of physicians and

59% of patients) felt that manipulation should be available in the

primary care setting. Although less than half (40%) of the physicians

reported any educational exposure to MM and less than one-quarter (20%)

have administered MM in their practice, most (71%) respondents endorsed

desiring more instruction in MM.

Another small study examined the interest and ability of MD residents

in learning osteopathic principles and skills, including OMT. It showed

that after a 1-month elective rotation, the MD residents responded

favorably to the experience.

Professional attitudes

In

1998, a New York Times article described the increasing numbers, public

awareness, and mainstreaming of osteopathic medical physicians,

illustrating an increasingly cooperative climate between the DO and MD

professions.

In 2005, during his tenure as president of the Association of American Medical Colleges, Jordan Cohen described a climate of cooperation between DO and MD practitioners:

"We now find ourselves living at a time when osteopathic and allopathic graduates are both sought after by many of the same residency programs; are in most instances both licensed by the same licensing boards; are both privileged by many of the same hospitals; and are found in appreciable numbers on the faculties of each other's medical schools".

International practice rights

International practice rights of US trained DOs

Each country has different requirements and procedures for licensing

or registering osteopathic physicians and osteopaths. The only

osteopathic practitioners that the US Department of Education recognizes as physicians are graduates of osteopathic medical colleges in the United States.

Therefore, osteopaths who have trained outside the United States are

not eligible for medical licensure in the United States. On the other

hand, US-trained DOs are currently able to practice in 45 countries with

full medical rights and in several others with restricted rights.

The Bureau on International Osteopathic Medical Education and Affairs

(BIOMEA) is an independent board of the American Osteopathic

Association. The BIOMEA monitors the licensing and registration

practices of physicians in countries outside of the United States and

advances the recognition of American-trained DOs. Towards this end, the

BIOMEA works with international health organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO), the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) as well as other groups.

The procedure by which countries consider granting physician

licensure to foreigners varies widely. For US-trained physicians, the

ability to qualify for "unlimited practice rights" also varies according

to one's degree, MD or DO.

Many countries recognize US-trained MDs as applicants for licensure,

granting successful applicants "unlimited" practice rights. The American

Osteopathic Association has lobbied the governments of other countries

to recognize US-trained DOs similarly to their MD counterparts, with

some success.

In over 65 countries, US-trained DOs have unlimited practice rights. In 2005, after one year of deliberations, the General Medical Council

announced that US-trained DOs will be accepted for full medical

practice rights in the United Kingdom. According to Josh Kerr of the

AOA, "some countries don’t understand the differences in training

between an osteopathic physician and an osteopath."

The American Medical Student Association strongly advocates for

US-trained DO international practice rights "equal to that" of

MD-qualified physicians.

Osteopathic medicine and primary care

Trends in primary care as a career choice of osteopathic medical students 4th year students 1st year students

Osteopathic physicians have historically entered primary care fields

at a higher rate than their MD counterparts. Some osteopathic

organizations make claims to a greater emphasis on the importance of

primary care within osteopathic medicine. However, the proportion of

osteopathic students choosing primary care fields, like that of their MD

peers, is declining. Currently, only one in five osteopathic medical students enters a family medicine residency (the largest primary care field).

In 2004, only 32% of osteopathic seniors planned careers in any primary

care field; this percentage was down from a peak in 1996 of more than

50%.

Criticism and internal debate

First-year enrollment at osteopathic medical schools, 1968–2011

OMT

Traditional osteopathic medicine, specifically OMT, has been criticized for many techniques such as cranial and cranio-sacral manipulation. A study performed in the early 2000s questioned the therapeutic utility of osteopathic manipulative treatment modalities. Also, New York University

health information website claims that "it is difficult to properly

ascertain the effectiveness of a hands-on therapy like OMT."

Research emphasis

Another area of criticism has been the relative lack of research and

lesser emphasis on scientific inquiry at DO schools in comparison with

MD schools.

The inability to institutionalize research, particularly clinical research, at osteopathic institutions has, over the years, weakened the acculturation, socialization, and distinctive beliefs and practices of osteopathic students and graduates.

Identity crisis

There

is currently a debate within the osteopathic community over the

feasibility of maintaining osteopathic medicine as a distinct entity

within US health care. JD Howell, author of The Paradox of Osteopathy,

notes claims of a "fundamental yet ineffable difference" between MD and

DO qualified physicians are based on practices such as "preventive

medicine and seeing patients in a sociological context" that are "widely

encountered not only in osteopathic medicine but also in allopathic

medicine."

Studies have confirmed the lack of any "philosophic concept or

resultant practice behavior" that would distinguish a DO from an MD Howell summarizes the questions framing the debate over the future of osteopathic distinctiveness thus:

If osteopathy has become the functional equivalent of allopathy [meaning the MD profession], what is the justification for its continued existence? And if there is value in therapy that is uniquely osteopathic, why should its use be limited to osteopaths?

Rapid expansion

As

the number of osteopathic schools has increased, the debate over

distinctiveness has often seen the leadership of the American

Osteopathic Association at odds with the community of osteopathic

physicians.

within the osteopathic community, the growth is drawing attention to the identity crisis faced by [the profession]. While osteopathic leaders emphasize osteopaths' unique identity, many osteopaths would rather not draw attention to their uniqueness.

The rapid expansion has raised concerns about the number of available

faculty at osteopathic schools and the role that those faculty play in

maintaining the integrity of the academic program of the schools. Norman Gevitz, author of the leading text on the history of osteopathic medicine, recently published,

DO schools are currently expanding their class sizes much more quickly than are their MD counterparts. Unlike MD colleges, where it is widely known that academic faculty members—fearing dilution of quality as well as the prospect of an increased teaching workload—constitute a powerful inhibiting force to expand the class size, osteopathic faculty at private osteopathic schools have traditionally had little or no input on such matters. Instead, these decisions are almost exclusively the responsibility of college administrators and their boards of trustees, who look at such expansion from an entrepreneurial as well as an educational perspective. Osteopathic medical schools can keep the cost of student body expansion relatively low compared with that of MD institutions. Although the standards of the Commission on Osteopathic College Accreditation ensure that there will be enough desks and lab spaces to accommodate all new students, they do not mandate that an osteopathic college must bear the expense of maintaining a high full-time-faculty:student ratio.

The president of the American Association of Colleges of Osteopathic

Medicine commented on the current climate of crisis within the

profession.

The simultaneous movement away from osteopathic medicine’s traditionally separate training and practice systems, when coupled with its rapid growth, has created a sense of crisis as to its future. The rapid rate of growth has raised questions as to the availability of clinical and basic science faculty and clinical resources to accommodate the increasing load of students.