https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Desktop_environment

In computing, a desktop environment (DE) is an implementation of the desktop metaphor made of a bundle of programs running on top of a computer operating system, which share a common graphical user interface (GUI), sometimes described as a graphical shell. The desktop environment was seen mostly on personal computers until the rise of mobile computing. Desktop GUIs help the user to easily access and edit files, while they usually do not provide access to all of the features found in the underlying operating system. Instead, the traditional command-line interface (CLI) is still used when full control over the operating system is required.

A desktop environment typically consists of icons, windows, toolbars, folders, wallpapers and desktop widgets. A GUI might also provide drag and drop functionality and other features that make the desktop metaphor more complete. A desktop environment aims to be an intuitive way for the user to interact with the computer using concepts which are similar to those used when interacting with the physical world, such as buttons and windows.

While the term desktop environment originally described a style of user interfaces following the desktop metaphor, it has also come to describe the programs that realize the metaphor itself. This usage has been popularized by projects such as the Common Desktop Environment, K Desktop Environment, and GNOME.

In computing, a desktop environment (DE) is an implementation of the desktop metaphor made of a bundle of programs running on top of a computer operating system, which share a common graphical user interface (GUI), sometimes described as a graphical shell. The desktop environment was seen mostly on personal computers until the rise of mobile computing. Desktop GUIs help the user to easily access and edit files, while they usually do not provide access to all of the features found in the underlying operating system. Instead, the traditional command-line interface (CLI) is still used when full control over the operating system is required.

A desktop environment typically consists of icons, windows, toolbars, folders, wallpapers and desktop widgets. A GUI might also provide drag and drop functionality and other features that make the desktop metaphor more complete. A desktop environment aims to be an intuitive way for the user to interact with the computer using concepts which are similar to those used when interacting with the physical world, such as buttons and windows.

While the term desktop environment originally described a style of user interfaces following the desktop metaphor, it has also come to describe the programs that realize the metaphor itself. This usage has been popularized by projects such as the Common Desktop Environment, K Desktop Environment, and GNOME.

Implementation

On a system that offers a desktop environment, a window manager in conjunction with applications written using a widget toolkit are generally responsible for most of what the user sees. The window manager supports the user interactions with the environment, while the toolkit provides developers a software library for applications with a unified look and behavior.

A windowing system of some sort generally interfaces directly with the underlying operating system

and libraries. This provides support for graphical hardware, pointing

devices, and keyboards. The window manager generally runs on top of this

windowing system. While the windowing system may provide some window

management functionality, this functionality is still considered to be

part of the window manager, which simply happens to have been provided

by the windowing system.

Applications that are created with a particular window manager in mind usually make use of a windowing toolkit, generally provided with the operating system or window manager. A windowing toolkit gives applications access to widgets that allow the user to interact graphically with the application in a consistent way.

History and common use

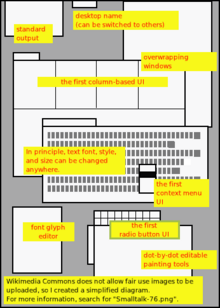

The interim Dynabook desktop environment (1976; aka Smalltalk-76 running on Alto)

The first desktop environment was created by Xerox and was sold with the Xerox Alto

in the 1970s. The Alto was generally considered by Xerox to be a

personal office computer; it failed in the marketplace because of poor

marketing and a very high price tag.[dubious ][2] With the Lisa, Apple introduced a desktop environment on an affordable personal computer, which also failed in the market.

The desktop metaphor was popularized on commercial personal computers by the original Macintosh from Apple in 1984, and was popularized further by Windows from Microsoft since the 1990s. As of 2014, the most popular desktop environments are descendants of these earlier environments, including the Aero environment used in Windows Vista and Windows 7, and the Aqua environment used in macOS. When compared with the X-based desktop environments available for Unix-like operating systems such as Linux and FreeBSD, the proprietary

desktop environments included with Windows and macOS have relatively

fixed layouts and static features, with highly integrated "seamless"

designs that aim to provide mostly consistent customer experiences

across installations.

Microsoft Windows dominates in marketshare among personal

computers with a desktop environment. Computers using Unix-like

operating systems such as macOS, Chrome OS, Linux, BSD or Solaris are

much less common; however, as of 2015 there is a growing market for low-cost Linux PCs using the X Window System or Wayland with a broad choice of desktop environments. Among the more popular of these are Google's Chromebooks and Chromeboxes, Intel's NUC, the Raspberry Pi, etc.

On tablets and smartphones, the situation is the opposite, with

Unix-like operating systems dominating the market, including the iOS (BSD-derived), Android, Tizen, Sailfish and Ubuntu (all Linux-derived). Microsoft's Windows phone, Windows RT and Windows 10

are used on a much smaller number of tablets and smartphones. However,

the majority of Unix-like operating systems dominant on handheld devices

do not use the X11 desktop environments used by other Unix-like

operating systems, relying instead on interfaces based on other

technologies.

Desktop environments for the X Window System

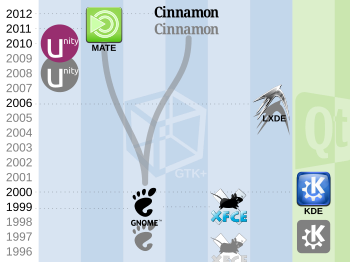

A

brief timeline of the most popular modern desktop environments for

Unix-like operating systems (greyscale logos indicate when the project's

development started, while colorized logos indicate the project's first

release)

On systems running the X Window System (typically Unix-family systems such as Linux, the BSDs, and formal UNIX

distributions), desktop environments are much more dynamic and

customizable to meet user needs. In this context, a desktop environment

typically consists of several separate components, including a window manager (such as Mutter or KWin), a file manager (such as Files or Dolphin), a set of graphical themes, together with toolkits (such as GTK+ and Qt) and libraries

for managing the desktop. All these individual modules can be exchanged

and independently configured to suit users, but most desktop

environments provide a default configuration that works with minimal

user setup.

Some window managers—such as IceWM, Fluxbox, Openbox, ROX Desktop and Window Maker—contain relatively sparse desktop environment elements, such as an integrated spatial file manager, while others like evilwm and wmii

do not provide such elements. Not all of the program code that is part

of a desktop environment has effects which are directly visible to the

user. Some of it may be low-level code. KDE, for example, provides so-called KIO

slaves which give the user access to a wide range of virtual devices.

These I/O slaves are not available outside the KDE environment.

In 1996 the KDE was announced, followed in 1997 by the announcement of GNOME. Xfce is a smaller project that was also founded in 1996, and focuses on speed and modularity, just like LXDE which was started in 2006. A comparison of X Window System desktop environments demonstrates the differences between environments. GNOME and KDE were usually seen as dominant solutions, and these are still often installed by default on Linux systems. Each of them offers:

- To programmers, a set of standard APIs, a programming environment, and human interface guidelines.

- To translators, a collaboration infrastructure. KDE and GNOME are available in many languages.

- To artists, a workspace to share their talents.

- To ergonomics specialists, the chance to help simplify the working environment.

- To developers of third-party applications, a reference environment for integration. OpenOffice.org is one such application.

- To users, a complete desktop environment and a suite of essential applications. These include a file manager, web browser, multimedia player, email client, address book, PDF reader, photo manager, and system preferences application.

In the early 2000s, KDE reached maturity. The Appeal and ToPaZ

projects focused on bringing new advances to the next major releases of

both KDE and GNOME respectively. Although striving for broadly similar

goals, GNOME and KDE do differ in their approach to user ergonomics. KDE

encourages applications to integrate and interoperate, is highly

customizable, and contains many complex features, all whilst trying to

establish sensible defaults. GNOME on the other hand is more

prescriptive, and focuses on the finer details of essential tasks and

overall simplification. Accordingly, each one attracts a different user

and developer community. Technically, there are numerous technologies

common to all Unix-like desktop environments, most obviously the X Window System. Accordingly, the freedesktop.org project was established as an informal collaboration zone with the goal being to reduce duplication of effort.

As GNOME and KDE focus on high-performance computers, users of

less powerful or older computers often prefer alternative desktop

environments specifically created for low-performance systems. Most

commonly used lightweight desktop environments include LXDE and Xfce; they both use GTK+, which is the same underlying toolkit GNOME uses. The MATE

desktop environment, a fork of GNOME 2, is comparable to Xfce in its

use of RAM and processor cycles, but is often considered more as an

alternative to other lightweight desktop environments.

For a while, GNOME and KDE enjoyed the status of the most popular

Linux desktop environments; later, other desktop environments grew in

popularity. In April 2011, GNOME introduced a new interface concept with

its version 3, while a popular Linux distribution Ubuntu introduced its own new desktop environment, Unity. Some users preferred to keep the traditional interface concept of GNOME 2, resulting in the creation of MATE as a GNOME 2 fork.

Examples of desktop environments

The most common desktop environment on personal computers is Microsoft Windows' built-in interface. It was titled Luna in Windows XP, Aero in Windows Vista and Windows 7, Metro in Windows 8 and 8.1, and Fluent in Windows 10. Also common is Aqua, included with Apple's macOS.

Mainstream desktop environments for Unix-like operating systems use the X Window System, and include KDE, GNOME, Xfce, and LXDE, any of which may be selected by users and are not tied exclusively to the operating system in use.

A number of other desktop environments also exist, including (but not limited to) CDE, EDE, GEM, IRIX Interactive Desktop, Sun's Java Desktop System, Jesktop, Mezzo, Project Looking Glass, ROX Desktop, UDE, Xito, XFast. Moreover, there exists FVWM-Crystal, which consists of a powerful configuration for the FVWM window manager, a theme and further adds, altogether forming a "construction kit" for building up a desktop environment.

X window managers

that are meant to be usable stand-alone — without another desktop

environment — also include elements reminiscent of those found in

typical desktop environments, most prominently Enlightenment. Other examples include OpenBox, Fluxbox, WindowLab, Fvwm, as well as Window Maker and AfterStep, which both feature the NeXTSTEP GUI look and feel. However newer versions of some operating systems make self configure.

The Amiga approach to desktop environment was noteworthy: the original Workbench desktop environment in AmigaOS

evolved through time to originate an entire family of descendants and

alternative desktop solutions. Some of those descendants are the Scalos, the Ambient desktop of MorphOS, and the Wanderer desktop of the AROS open source OS. WindowLab also contains features reminiscent of the Amiga UI. Third-party Directory Opus software, which was originally just a navigational file manager program, evolved to become a complete Amiga desktop replacement called Directory Opus Magellan.

The BumpTop

project is an experimental desktop environment. Its main objective is

to replace the 2D paradigm with a "real-world" 3D implementation, where

documents can be freely manipulated across a virtual table.