From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Synesthesia |

|---|

| Other names | Synaesthesia |

|---|

|

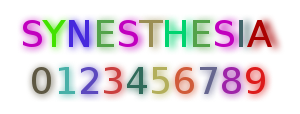

| How

someone with synesthesia might perceive certain letters and numbers.

Synesthetes see characters just as others do (in whichever color

actually displayed) but may simultaneously perceive colors as associated

with or evoked by each one. |

| Specialty | Psychiatry, neurology |

|---|

Synesthesia or synaesthesia is a perceptual phenomenon in which stimulation of one sensory or cognitive pathway leads to involuntary experiences in a second sensory or cognitive pathway. People who report a lifelong history of such experiences are known as synesthetes. Awareness of synesthetic perceptions varies from person to person. In one common form of synesthesia, known as grapheme–color synesthesia or color–graphemic synesthesia, letters or numbers are perceived as inherently colored. In spatial-sequence, or number form

synesthesia, numbers, months of the year, or days of the week elicit

precise locations in space (for example, 1980 may be "farther away" than

1990), or may appear as a three-dimensional map (clockwise or

counterclockwise). Synesthetic associations can occur in any combination and any number of senses or cognitive pathways.

Little is known about how synesthesia develops. It has been

suggested that synesthesia develops during childhood when children are

intensively engaged with abstract concepts for the first time. This hypothesis – referred to as semantic vacuum hypothesis

– explains why the most common forms of synesthesia are grapheme-color,

spatial sequence and number form. These are usually the first abstract

concepts that educational systems require children to learn.

Difficulties have been recognized in adequately defining synesthesia.

Many different phenomena have been included in the term synesthesia

("union of the senses"), and in many cases the terminology seems to be

inaccurate. A more accurate but less common term may be ideasthesia.

The earliest recorded case of synesthesia is attributed to the Oxford University academic and philosopher John Locke, who, in 1690, made a report about a blind man who said he experienced the color scarlet when he heard the sound of a trumpet. However, there is disagreement as to whether Locke described an actual instance of synesthesia or was using a metaphor. The first medical account came from German physician Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs in 1812. The term is from the Ancient Greek σύν syn, 'together', and αἴσθησις aisthēsis, 'sensation'.

Types

There are two overall forms of synesthesia:

- projective synesthesia: people who see actual colors, forms, or

shapes when stimulated (the widely understood version of synesthesia).

- associative synesthesia: people who feel a very strong and

involuntary connection between the stimulus and the sense that it

triggers.

For example, in chromesthesia (sound to color), a projector may hear a trumpet, and see an orange triangle in space, while an associator might hear a trumpet, and think very strongly that it sounds "orange".

Synesthesia can occur between nearly any two senses or perceptual modes, and at least one synesthete, Solomon Shereshevsky, experienced synesthesia that linked all five senses.

Types of synesthesia are indicated by using the notation x → y, where x

is the "inducer" or trigger experience, and y is the "concurrent" or

additional experience. For example, perceiving letters and numbers

(collectively called graphemes)

as colored would be indicated as grapheme → color synesthesia.

Similarly, when synesthetes see colors and movement as a result of

hearing musical tones, it would be indicated as tone → (color, movement)

synesthesia.

While nearly every logically possible combination of experiences can occur, several types are more common than others.

Grapheme-color synesthesia

In one of the most common forms of synesthesia, individual letters of the alphabet and numbers (collectively referred to as graphemes)

are "shaded" or "tinged" with a color. While different individuals

usually do not report the same colors for all letters and numbers,

studies with large numbers of synesthetes find some commonalities across

letters (e.g., A is likely to be red).

Chromesthesia

Another common form of synesthesia is the association of sounds with

colors. For some, everyday sounds such as doors opening, cars honking,

or people talking can trigger seeing colors. For others, colors are

triggered when musical notes or keys are being played. People with

synesthesia related to music may also have perfect pitch because their ability to see/hear colors aids them in identifying notes or keys.

The colors triggered by certain sounds, and any other synesthetic visual experiences, are referred to as photisms.

According to Richard Cytowic,

chromesthesia is "something like fireworks": voice, music, and assorted

environmental sounds such as clattering dishes or dog barks trigger

color and firework shapes that arise, move around, and then fade when

the sound ends. Sound often changes the perceived hue, brightness,

scintillation, and directional movement. Some individuals see music on a

"screen" in front of their faces. For Deni Simon, music produces waving

lines "like oscilloscope configurations – lines moving in color, often

metallic with height, width and, most importantly, depth. My favorite

music has lines that extend horizontally beyond the 'screen' area."

Individuals rarely agree on what color a given sound is. B flat might be orange for one person and blue for another. Composers Franz Liszt and Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov famously disagreed on the colors of musical keys.

Spatial sequence synesthesia

Those

with spatial sequence synesthesia (SSS) tend to see numerical sequences

as points in space. For instance, the number 1 might be farther away

and the number 2 might be closer. People with SSS may have superior

memories; in one study, they were able to recall past events and

memories far better and in far greater detail than those without the

condition. They also see months or dates in the space around them. Some

people see time like a clock above and around them.

Number form

A

number form is a mental map of numbers that automatically and

involuntarily appear whenever someone who experiences number-forms

synesthesia thinks of numbers. These numbers might appear in different

locations and the mapping changes and varies between individuals. Number

forms were first documented and named in 1881 by Francis Galton in "The Visions of Sane Persons".

It is suggested that this might be caused by “cross activation” of the

neural pathway that connects the parietal lobes and angular gyrus. Both

of these areas are involved in numerical cognition and spatial cognition

respectively.

A

number form from one of Francis Galton's subjects (1881). Note how the first 4 digits roughly correspond to their positions on a clock face.

Auditory-tactile synesthesia

In auditory-tactile synesthesia,

certain sounds can induce sensations in parts of the body. For example,

someone with auditory-tactile synesthesia may experience that hearing a

specific word or sound feels like touch in one specific part of the

body or may experience that certain sounds can create a sensation in the

skin without being touched. Not to be confused with the milder general

reaction known as frisson, which affects approx 50% of the population. It is one of the least common forms of synesthesia.

Ordinal linguistic personification

Ordinal-linguistic personification (OLP, or personification for

short) is a form of synesthesia in which ordered sequences, such as ordinal numbers, week-day names, months and alphabetical letters are associated with personalities or genders (Simner & Hubbard 2006).

For example, the number 2 might be a young boy with a short temper, or

the letter G might be a busy mother with a kind face. Although this form

of synesthesia was documented as early as the 1890s (Flournoy 1893; Calkins 1893) researchers have, until recently, paid little attention to this form (see History of synesthesia research). This form of synesthesia was named as OLP in the contemporary literature by Julia Simner and colleagues although it is now also widely recognised by the term

"sequence-personality" synesthesia. Ordinal linguistic personification

normally co-occurs with other forms of synesthesia such as grapheme-color synesthesia.

Misophonia

Misophonia

is a neurological disorder in which negative experiences (anger,

fright, hatred, disgust) are triggered by specific sounds. Cytowic

suggests that misophonia is related to, or perhaps a variety of,

synesthesia.

Edelstein and her colleagues have compared misophonia to synesthesia in

terms of connectivity between different brain regions as well as

specific symptoms.

They formed the hypothesis that "a pathological distortion of

connections between the auditory cortex and limbic structures could

cause a form of sound-emotion synesthesia."

Studies suggest that individuals with misophonia have a normal hearing

sensitivity level but the limbic system and autonomic nervous system are

constantly in a “heightened state of arousal” where abnormal reactions

to sounds will be more prevalent.

Newer studies suggest that depending on its severity, misophonia

could be associated with lower cognitive control when individuals are

exposed to certain associations and triggers.

It is unclear what causes misophonia. Some scientists believe it

could be genetic, others believe it to be present with other additional

conditions however there is not enough evidence to conclude what causes

it. There are no current treatments for the condition but could be managed with different types of coping strategies.

These strategies vary from person to person, some have reported the

avoidance of certain situations that could trigger the reaction:

mimicking the sounds, cancelling out the sounds by using different

methods like earplugs, music, internal dialog and many other tactics.

Most misophonics use these to “overwrite” these sounds produced by

others.

Mirror-touch synesthesia

This is a form of synesthesia where individuals feel the same

sensation that another person feels (such as touch). For instance, when

such a synesthete observes someone being tapped on their shoulder, the

synesthete involuntarily feels a tap on their own shoulder as well.

People with this type of synesthesia have been shown to have higher empathy levels compared to the general population. This may be related to the so-called mirror neurons present in the motor areas of the brain, which have also been linked to empathy.

Lexical-gustatory synesthesia

This is another form of synesthesia where certain tastes are

experienced when hearing words. For example, the word basketball might

taste like waffles. The documentary 'Derek Tastes Of Earwax' gets its

name from this phenomenon, in references to pub owner James Wannerton

who experiences this particular sensation whenever he hears the name

spoken. It is estimated that 0.2% of the synesthesia population has this form of synesthesia, making it the rarest form.

Kinesthetic synesthesia

Kinesthetic synesthesia is one of the rarest documented forms of synesthesia in the world.

This form of synesthesia is a combination of various different types of

synesthesia. Features appear similar to auditory-tactile synesthesia

but sensations are not isolated to individual numbers or letters but

complex systems of relationships. The result is the ability to memorize

and model complex relationships between numerous variables by feeling

physical sensations around the kinesthetic movement of related

variables. Reports include feeling sensations in the hands or feet,

coupled with visualizations of shapes or objects, when analyzing

mathematical equations, physical systems, or music. In another case, a

person described seeing interactions between physical shapes causing

sensations in the feet when solving a math problem. Generally, those

with this type of synesthesia can memorize and visualize complicated

systems, and with a high degree of accuracy, predict the results of

changes to the system. Examples include predicting the results of

computer simulations in subjects such as quantum mechanics or fluid

dynamics when results are not naturally intuitive.

Other forms

Other

forms of synesthesia have been reported, but little has been done to

analyze them scientifically. There are at least 80 types of synesthesia.

In August 2017 a research article in the journal Social Neuroscience reviewed studies with fMRI to determine if persons who experience autonomous sensory meridian response

are experiencing a form of synesthesia. While a determination has not

yet been made, there is anecdotal evidence that this may be the case,

based on significant and consistent differences from the control group,

in terms of functional connectivity within neural pathways. It is

unclear whether this will lead to ASMR being included as a form of

existing synesthesia, or if a new type will be considered.

Signs and symptoms

Some

synesthetes often report that they were unaware their experiences were

unusual until they realized other people did not have them, while others

report feeling as if they had been keeping a secret their entire lives.

The automatic and ineffable nature of a synesthetic experience means

that the pairing may not seem out of the ordinary. This involuntary and

consistent nature helps define synesthesia as a real experience. Most

synesthetes report that their experiences are pleasant or neutral,

although, in rare cases, synesthetes report that their experiences can

lead to a degree of sensory overload.

Though often stereotyped in the popular media as a medical

condition or neurological aberration, many synesthetes themselves do not

perceive their synesthetic experiences as a handicap. On the contrary,

some report it as a gift—an additional "hidden" sense—something they

would not want to miss. Most synesthetes become aware of their

distinctive mode of perception in their childhood. Some have learned how

to apply their ability in daily life and work. Synesthetes have used

their abilities in memorization of names and telephone numbers, mental

arithmetic, and more complex creative activities like producing visual

art, music, and theater.

Despite the commonalities which permit definition of the broad

phenomenon of synesthesia, individual experiences vary in numerous ways.

This variability was first noticed early in synesthesia research. Some synesthetes report that vowels are more strongly colored, while for others consonants are more strongly colored.

Self reports, interviews, and autobiographical notes by synesthetes

demonstrate a great degree of variety in types of synesthesia, intensity

of synesthetic perceptions, awareness of the perceptual discrepancies

between synesthetes and non-synesthetes, and the ways synesthesia is

used in work, creative processes, and daily life.

Synesthetes are very likely to participate in creative activities.

It has been suggested that individual development of perceptual and

cognitive skills, in addition to one's cultural environment, produces

the variety in awareness and practical use of synesthetic phenomena.

Synesthesia may also give a memory advantage. In one study, conducted

by Julia Simner of the University of Edinburgh, it was found that

spatial sequence synesthetes have a built-in and automatic mnemonic

reference. So the non-synesthete will need to create a mnemonic device

to remember a sequence (like dates in a diary), but the synesthete can

simply reference their spatial visualizations.

Mechanism

Regions thought to be cross-activated in grapheme-color synesthesia (green=grapheme recognition area, red=

V4 color area)

As of 2015, the neurological correlates of synesthesia had not been established.

Dedicated regions of the brain are specialized for given

functions. Increased cross-talk between regions specialized for

different functions may account for the many types of synesthesia. For

example, the additive experience of seeing color when looking at

graphemes might be due to cross-activation of the grapheme-recognition

area and the color area called V4 (see figure).

This is supported by the fact that grapheme-color synesthetes are able

to identify the color of a grapheme in their peripheral vision even when

they cannot consciously identify the shape of the grapheme.

An alternative possibility is disinhibited feedback, or a

reduction in the amount of inhibition along normally existing feedback

pathways.

Normally, excitation and inhibition are balanced. However, if normal

feedback were not inhibited as usual, then signals feeding back from

late stages of multi-sensory processing might influence earlier stages

such that tones could activate vision. Cytowic and Eagleman find support

for the disinhibition idea in the so-called acquired forms of synesthesia that occur in non-synesthetes under certain conditions: temporal lobe epilepsy, head trauma, stroke, and brain tumors. They also note that it can likewise occur during stages of meditation, deep concentration, sensory deprivation, or with use of psychedelics such as LSD or mescaline, and even, in some cases, marijuana. However, synesthetes report that common stimulants, like caffeine and cigarettes do not affect the strength of their synesthesia, nor does alcohol.

A very different theoretical approach to synesthesia is that based on ideasthesia. According to this account, synesthesia is a phenomenon mediated by the extraction of the meaning of the inducing stimulus. Thus, synesthesia may be fundamentally a semantic

phenomenon. Therefore, to understand neural mechanisms of synesthesia

the mechanisms of semantics and the extraction of meaning need to be

understood better. This is a non-trivial issue because it is not only a

question of a location in the brain at which meaning is "processed" but

pertains also to the question of understanding—epitomized in e.g., the Chinese room problem. Thus, the question of the neural basis of synesthesia is deeply entrenched into the general mind–body problem and the problem of the explanatory gap.

Genetics

The genetic mechanism of synesthesia has long been debated. Due to

the prevalence of synesthesia among the first-degree relatives of

synesthetes, there is evidence that synesthesia might have a genetic basis, however the monozygotic twins case studies indicate there is an epigenetic component. Synesthesia might also be an oligogenic condition, with locus heterogeneity,

multiple forms of inheritance (including Mendelian in some cases), and

continuous variation in gene expression. It has been found that women

have a higher chance of developing Synesthesia, and in the UK, females

are 8 times more likely to have it than men (reasons are unknown). When

people are left-handed it is inherited, and researchers have discovered

that synesthetes have a higher probability of being left-handed than the

general population.

Diagnosis

Although often termed a "neurological condition," synesthesia is not listed in either the DSM-IV or the ICD since it usually does not interfere with normal daily functioning. Indeed, most synesthetes report that their experiences are neutral or even pleasant. Like perfect pitch, synesthesia is simply a difference in perceptual experience.

Reaction

times for answers that are congruent with a synesthete's automatic

colors are shorter than those whose answers are incongruent.

Synesthesia Test Variations

A number of tests exist for synesthesia. Each common type has a

specific test. When testing for grapheme-color synesthesia a visual test

is given. The person is shown a picture that includes black letters and

numbers. A synesthete will associate the letters and numbers with a

specific color. An auditory test is another way to test for synesthesia.

A sound is turned on and one will either identify it with a taste, or

envision shapes. The audio test correlates with chromesthesia (sounds

with colors). Since people question whether or not synesthesia is tied

to memory the "retest" is given. One is given a set of objects and is

asked to assign colors, tastes, personalities, or more. After a period

of time, the same objects are presented and the person is asked again to

do the same task. The synesthete is able to assign the same

characteristics, because that person has permanent neural associations

in the brain, rather than memories of a certain object. The simplest

approach is test-retest reliability over long periods of time, using

stimuli of color names, color chips, or a computer-screen color picker

providing 16.7 million choices. Synesthetes consistently score around

90% on reliability of associations, even with years between tests.

In contrast, non-synesthetes score just 30–40%, even with only a few

weeks between tests and a warning that they would be retested.

The automaticity of synesthetic experience. A synesthete might perceive the left panel like the panel on the right.

Grapheme-color synesthetes, as a group, share significant preferences

for the color of each letter (e.g., A tends to be red; O tends to be

white or black; S tends to be yellow etc.)

Nonetheless, there is a great variety in types of synesthesia, and

within each type, individuals report differing triggers for their

sensations and differing intensities of experiences. This variety means

that defining synesthesia in an individual is difficult, and the

majority of synesthetes are completely unaware that their experiences

have a name.

Neurologist Richard Cytowic identifies the following diagnostic criteria for synesthesia in his first edition book. However, the criteria are different in the second book:

- Synesthesia is involuntary and automatic.

- Synesthetic perceptions are spatially extended, meaning they often

have a sense of "location." For example, synesthetes speak of "looking

at" or "going to" a particular place to attend to the experience.

- Synesthetic percepts are consistent and generic (i.e., simple rather than pictorial).

- Synesthesia is highly memorable.

- Synesthesia is laden with affect.

Cytowic's early cases mainly included individuals whose synesthesia

was frankly projected outside the body (e.g., on a "screen" in front of

one's face). Later research showed that such stark externalization

occurs in a minority of synesthetes. Refining this concept, Cytowic and Eagleman

differentiated between "localizers" and "non-localizers" to distinguish

those synesthetes whose perceptions have a definite sense of spatial

quality from those whose perceptions do not.

Prevalence

Estimates

of prevalence of synesthesia have ranged widely, from 1 in 4 to 1 in

25,000 - 100,000. However, most studies have relied on synesthetes

reporting themselves, introducing self-referral bias. In what is cited as the most accurate prevalence study so far,

self-referral bias was avoided by studying 500 people recruited from

the communities of Edinburgh and Glasgow Universities; it showed a

prevalence of 4.4%, with 9 different variations of synesthesia.

This study also concluded that one common form of

synesthesia—grapheme-color synesthesia (colored letters and numbers) –

is found in more than one percent of the population, and this latter

prevalence of graphemes-color synesthesia has since been independently

verified in a sample of nearly 3,000 people in the University of

Edinburgh.

The most common forms of synesthesia are those that trigger colors, and the most prevalent of all is day-color.

Also relatively common is grapheme-color synesthesia. We can think of

"prevalence" both in terms of how common is synesthesia (or different

forms of synesthesia) within the population, or how common are different

forms of synesthesia within synesthetes. So within synesthetes, forms

of synesthesia that trigger color also appear to be the most common

forms of synesthesia with a prevalence rate of 86% within synesthetes. In another study, music-color is also prevalent at 18–41%. Some of the rarest are reported to be auditory-tactile, mirror-touch, and lexical-gustatory.

There is research to suggest that the likelihood of having synesthesia is greater in people with autism.

History

The interest in colored hearing dates back to Greek antiquity, when philosophers asked if the color (chroia, what we now call timbre) of music was a quantifiable quality. Isaac Newton proposed that musical tones and color tones shared common frequencies, as did Goethe in his book Theory of Colours. There is a long history of building color organs such as the clavier à lumières on which to perform colored music in concert halls.

In further support of this notion, in Indian classical music, the

musical terms raga and rasa are also synonyms for color and (quality of)

taste, respectively.

The first medical description of "colored hearing" is in an 1812 thesis by the German physician Georg Tobias Ludwig Sachs. The "father of psychophysics," Gustav Fechner, reported the first empirical survey of colored letter photisms among 73 synesthetes in 1876, followed in the 1880s by Francis Galton. Carl Jung refers to "color hearing" in his Symbols of Transformation in 1912.

In the early 1920s, the Bauhaus teacher and musician Gertrud Grunow

researched the relationships between sound, color and movement and

developed a 'twelve-tone circle of colour' which was analogous with the

twelve-tone music of the Austrian composer Arnold Schönberg (1874-1951). She was a participant in at least one of the Congresses for Colour-Sound Research (German:Kongreß für Farbe-Ton-Forschung) held in Hamburg in the late 1920s and early 1930s.

Research into synesthesia proceeded briskly in several countries,

but due to the difficulties in measuring subjective experiences and the

rise of behaviorism, which made the study of any subjective experience taboo, synesthesia faded into scientific oblivion between 1930 and 1980.

As the 1980s cognitive revolution

made inquiry into internal subjective states respectable again,

scientists returned to synesthesia. Led in the United States by Larry

Marks and Richard Cytowic, and later in England by Simon Baron-Cohen and Jeffrey Gray,

researchers explored the reality, consistency, and frequency of

synesthetic experiences. In the late 1990s, the focus settled on

grapheme → color synesthesia, one of the most common

and easily studied types. Psychologists and neuroscientists study

synesthesia not only for its inherent appeal, but also for the insights

it may give into cognitive and perceptual processes that occur in

synesthetes and non-synesthetes alike. Synesthesia is now the topic of

scientific books and papers, PhD theses, documentary films, and even

novels.

Since the rise of the Internet in the 1990s, synesthetes began

contacting one another and creating web sites devoted to the condition.

These rapidly grew into international organizations such as the American Synesthesia Association, the UK Synaesthesia Association,

the Belgian Synesthesia Association, the Canadian Synesthesia

Association, the German Synesthesia Association, and the Netherlands

Synesthesia Web Community.

Society and culture

Notable cases

Solomon Shereshevsky, a newspaper reporter turned celebrated mnemonist, was discovered by Russian neuropsychologist, Alexander Luria, to have a rare fivefold form of synesthesia. Words and text were not only associated with highly vivid visuo-spatial imagery but also sound, taste, color, and sensation.

Shereshevsky could recount endless details of many things without form,

from lists of names to decades-old conversations, but he had great

difficulty grasping abstract concepts. The automatic, and nearly

permanent, retention of every detail due to synesthesia greatly

inhibited Shereshevsky's ability to understand what he read or heard.

Neuroscientist and author V.S. Ramachandran

studied the case of a grapheme-color synesthete who was also color

blind. While he couldn't see certain colors with his eyes, he could

still "see" those colors when looking at certain letters. Because he

didn't have a name for those colors, he called them "Martian colors."

Art

Other notable synesthetes come particularly from artistic professions

and backgrounds. Synesthetic art historically refers to multi-sensory

experiments in the genres of visual music, music visualization, audiovisual art, abstract film, and intermedia.

Distinct from neuroscience, the concept of synesthesia in the arts is

regarded as the simultaneous perception of multiple stimuli in one gestalt experience.

Neurological synesthesia has been a source of inspiration for artists, composers, poets, novelists, and digital artists. Vladimir Nabokov writes explicitly about synesthesia in several novels. Wassily Kandinsky (a synesthete) and Piet Mondrian (not a synesthete) both experimented with image-music congruence in their paintings. Alexander Scriabin composed colored music that was deliberately contrived and based on the circle of fifths, whereas Olivier Messiaen invented a new method of composition (the modes of limited transposition) specifically to render his bi-directional sound-color synesthesia. For example, the red rocks of Bryce Canyon are depicted in his symphony Des canyons aux étoiles...

("From the Canyons to the Stars"). New art movements such as literary

symbolism, non-figurative art, and visual music have profited from

experiments with synesthetic perception and contributed to the public

awareness of synesthetic and multi-sensory ways of perceiving.

Contemporary artists with synesthesia, such as Carol Steen and Marcia Smilack

(a photographer who waits until she gets a synesthetic response from

what she sees and then takes the picture), use their synesthesia to

create their artwork. Brandy Gale, a Canadian visual artist, experiences

an involuntary joining or crossing of any of her senses – hearing,

vision, taste, touch, smell and movement. Gale paints from life rather

than from photographs and by exploring the sensory panorama of each

locale attempts to capture, select, and transmit these personal

experiences.

David Hockney

perceives music as color, shape, and configuration and uses these

perceptions when painting opera stage sets (though not while creating

his other artworks). Kandinsky combined four senses: color, hearing,

touch, and smell. Nabokov described his grapheme-color synesthesia at length in his autobiography, Speak, Memory, and portrayed it in some of his characters.

In addition to Messiaen, whose three types of complex colors are

rendered explicitly in musical chord structures that he invented, other composers who reported synesthesia include Duke Ellington, Rimsky-Korsakov, and Jean Sibelius. Michael Torke is a contemporary example of a synesthetic composer. Physicist Richard Feynman describes his colored equations in his autobiography, What Do You Care What Other People Think?

Other notable synesthetes include musicians Billy Joel, Itzhak Perlman, Alexander Frey, Lorde, Brendon Urie, Ida Maria, Brian Chase and Patrick Stump; inventor Nikola Tesla; electronic musician Richard D. James a.k.a. Aphex Twin (who claims to be inspired by lucid dreams as well as music); and classical pianist Hélène Grimaud. Drummer Mickey Hart of The Grateful Dead wrote about his experiences with synaesthesia in his autobiography Drumming at the Edge of Magic. Pharrell Williams, of the groups The Neptunes and N.E.R.D., also experiences synesthesia and used it as the basis of the album Seeing Sounds. Singer/songwriter Marina and the Diamonds experiences music → color synesthesia and reports colored days of the week.

Some artists frequently mentioned as synesthetes did not, in fact, have the neurological condition. Scriabin's 1911 Prometheus, for example, is a deliberate contrivance whose color choices are based on the circle of fifths and appear to have been taken from Madame Blavatsky. The musical score has a separate staff marked luce whose "notes" are played on a color organ. Technical reviews appear in period volumes of Scientific American.

On the other hand, his older colleague Rimsky-Korsakov (who was

perceived as a fairly conservative composer) was, in fact, a synesthete.

French poets Arthur Rimbaud and Charles Baudelaire wrote of synesthetic experiences, but there is no evidence they were synesthetes themselves. Baudelaire's 1857 Correspondances

introduced the notion that the senses can and should intermingle.

Baudelaire participated in a hashish experiment by psychiatrist Jacques-Joseph Moreau and became interested in how the senses might affect each other. Rimbaud later wrote Voyelles (1871), which was perhaps more important than Correspondances in popularizing synesthesia. He later boasted "J'inventais la couleur des voyelles!" (I invented the colors of the vowels!).

Daniel Tammet wrote a book on his experiences with synesthesia called Born on a Blue Day.

Joanne Harris, author of Chocolat, is a synesthete who says she experiences colors as scents. Her novel Blueeyedboy features various aspects of synesthesia.

Ramin Djawadi, a composer best known for his work on composing the theme songs and scores for such TV series as Game of Thrones, Westworld and for the Iron Man movie, also has synesthesia. He says he tends to "associate colors with music, or music with colors."

Literature

Synesthesia is sometimes used as a plot device or way of developing a character's inner life. Author and synesthete Pat Duffy describes four ways in which synesthetic characters have been used in modern fiction.

- Synesthesia as Romantic

ideal: in which the condition illustrates the Romantic ideal of

transcending one's experience of the world. Books in this category

include The Gift by Vladimir Nabokov.

- Synesthesia as pathology: in which the trait is pathological. Books in this category include The Whole World Over by Julia Glass.

- Synesthesia as Romantic pathology: in which synesthesia is

pathological but also provides an avenue to the Romantic ideal of

transcending quotidian experience. Books in this category include Holly Payne’s The Sound of Blue and Anna Ferrara's The Woman Who Tried To Be Normal.

- Synesthesia as psychological health and balance: Painting Ruby Tuesday by Jane Yardley, and A Mango-Shaped Space by Wendy Mass.

Many literary depictions of synesthesia are not accurate. Some say

more about an author's interpretation of synesthesia than the phenomenon

itself.

Research

Tests

like this demonstrate that people do not attach sounds to visual shapes

arbitrarily. When people are given a choice between the words "Bouba"

and "Kiki", the left shape is almost always called "Kiki" while the

right is called "Bouba"

Research on synesthesia raises questions about how the brain combines

information from different sensory modalities, referred to as crossmodal perception or multisensory integration.

An example of this is the bouba/kiki effect. In an experiment first designed by Wolfgang Köhler, people are asked to choose which of two shapes is named bouba and which kiki. The angular shape, kiki, is chosen by 95–98% and bouba for the rounded one. Individuals on the island of Tenerife showed a similar preference between shapes called takete and maluma. Even 2.5-year-old children (too young to read) show this effect. Research indicated that in the background of this effect may operate a form of ideasthesia.

Researchers hope that the study of synesthesia will provide better understanding of consciousness and its neural correlates. In particular, synesthesia might be relevant to the philosophical problem of qualia,

given that synesthetes experience extra qualia (e.g., colored sound).

An important insight for qualia research may come from the findings that

synesthesia has the properties of ideasthesia, which then suggest a crucial role of conceptualization processes in generating qualia.

Technological applications

Synesthesia also has a number of practical applications, one of which is the use of 'intentional synesthesia' in technology.

The Voice (vOICe)

Peter Meijer developed a sensory substitution device for the visually impaired

called The vOICe (the capital letters "O," "I," and "C" in "vOICe" are

intended to evoke the expression "Oh I see"). The vOICe is a privately

owned research project, running without venture capital, that was first

implemented using low-cost hardware in 1991.

The vOICe is a visual-to-auditory sensory substitution device (SSD)

preserving visual detail at high resolution (up to 25,344 pixels).

The device consists of a laptop, head-mounted camera or computer

camera, and headphones. The vOICe converts visual stimuli of the

surroundings captured by the camera into corresponding aural

representations (soundscapes)

delivered to the user through headphones at a default rate of one

soundscape per second. Each soundscape is a left-to-right scan, with

height represented by pitch, and brightness by loudness.

The vOICe compensates for the loss of vision by converting information

from the lost sensory modality into stimuli in a remaining modality.