From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Genetic drift (allelic drift or the Sewall Wright effect) is the change in the frequency of an existing gene variant (allele) in a population due to random sampling of organisms. The alleles in the offspring are a sample of those in the parents, and chance has a role in determining whether a given individual survives and reproduces. A population's allele frequency is the fraction of the copies of one gene that share a particular form.

Genetic drift may cause gene variants to disappear completely and thereby reduce genetic variation. It can also cause initially rare alleles to become much more frequent and even fixed.

When there are few copies of an allele, the effect of genetic

drift is larger, and when there are many copies the effect is smaller.

In the middle of the 20th century, vigorous debates occurred over the

relative importance of natural selection versus neutral processes, including genetic drift. Ronald Fisher, who explained natural selection using Mendelian genetics, held the view that genetic drift plays at the most a minor role in evolution, and this remained the dominant view for several decades. In 1968, population geneticist Motoo Kimura rekindled the debate with his neutral theory of molecular evolution, which claims that most instances where a genetic change spreads across a population (although not necessarily changes in phenotypes) are caused by genetic drift acting on neutral mutations.

Analogy with marbles in a jar

The process of genetic drift can be illustrated using 20 marbles in a jar to represent 20 organisms in a population.

Consider this jar of marbles as the starting population. Half of the

marbles in the jar are red and half are blue, with each colour

corresponding to a different allele of one gene in the population. In

each new generation the organisms reproduce at random. To represent this

reproduction, randomly select a marble from the original jar and

deposit a new marble with the same colour into a new jar. This is the

"offspring" of the original marble, meaning that the original marble

remains in its jar. Repeat this process until there are 20 new marbles

in the second jar. The second jar will now contain 20 "offspring", or

marbles of various colours. Unless the second jar contains exactly 10

red marbles and 10 blue marbles, a random shift has occurred in the

allele frequencies.

If this process is repeated a number of times, the numbers of red

and blue marbles picked each generation will fluctuate. Sometimes a jar

will have more red marbles than its "parent" jar and sometimes more

blue. This fluctuation is analogous to genetic drift – a change in the

population's allele frequency resulting from a random variation in the

distribution of alleles from one generation to the next.

It is even possible that in any one generation no marbles of a

particular colour are chosen, meaning they have no offspring. In this

example, if no red marbles are selected, the jar representing the new

generation contains only blue offspring. If this happens, the red allele

has been lost permanently in the population, while the remaining blue

allele has become fixed: all future generations are entirely blue. In

small populations, fixation can occur in just a few generations.

In this simulation each black dot on a marble signifies that it has been chosen for copying (reproduction) one time. There is

fixation in the blue "allele" within five generations.

Probability and allele frequency

The mechanisms of genetic drift can be illustrated with a simplified example. Consider a very large colony of bacteria isolated in a drop of solution. The bacteria are genetically identical except for a single gene with two alleles labeled A and B. A and B

are neutral alleles meaning that they do not affect the bacteria's

ability to survive and reproduce; all bacteria in this colony are

equally likely to survive and reproduce. Suppose that half the bacteria

have allele A and the other half have allele B. Thus A and B each have allele frequency 1/2.

The drop of solution then shrinks until it has only enough food

to sustain four bacteria. All other bacteria die without reproducing.

Among the four who survive, there are sixteen possible combinations for the A and B alleles:

(A-A-A-A), (B-A-A-A), (A-B-A-A), (B-B-A-A),

(A-A-B-A), (B-A-B-A), (A-B-B-A), (B-B-B-A),

(A-A-A-B), (B-A-A-B), (A-B-A-B), (B-B-A-B),

(A-A-B-B), (B-A-B-B), (A-B-B-B), (B-B-B-B).

Since all bacteria in the original solution are equally likely to

survive when the solution shrinks, the four survivors are a random

sample from the original colony. The probability

that each of the four survivors has a given allele is 1/2, and so the

probability that any particular allele combination occurs when the

solution shrinks is

(The original population size is so large that the sampling

effectively happens with replacement). In other words, each of the

sixteen possible allele combinations is equally likely to occur, with

probability 1/16.

Counting the combinations with the same number of A and B, we get the following table.

| A

|

B

|

Combinations

|

Probability

|

| 4

|

0

|

1

|

1/16

|

| 3

|

1

|

4

|

4/16

|

| 2

|

2

|

6

|

6/16

|

| 1

|

3

|

4

|

4/16

|

| 0

|

4

|

1

|

1/16

|

As shown in the table, the total number of combinations that have the same number of A alleles as of B

alleles is six, and the probability of this combination is 6/16. The

total number of other combinations is ten, so the probability of unequal

number of A and B alleles is 10/16. Thus, although the original colony began with an equal number of A and B

alleles, it is very possible that the number of alleles in the

remaining population of four members will not be equal. Equal numbers is

actually less likely than unequal numbers. In the latter case, genetic

drift has occurred because the population's allele frequencies have

changed due to random sampling. In this example the population

contracted to just four random survivors, a phenomenon known as population bottleneck.

The probabilities for the number of copies of allele A (or B) that survive (given in the last column of the above table) can be calculated directly from the binomial distribution where the "success" probability (probability of a given allele being present) is 1/2 (i.e., the probability that there are k copies of A (or B) alleles in the combination) is given by

where n=4 is the number of surviving bacteria.

Mathematical models

Mathematical models of genetic drift can be designed using either branching processes or a diffusion equation describing changes in allele frequency in an idealised population.

Wright–Fisher model

Consider a gene with two alleles, A or B. In diploid populations consisting of N individuals there are 2N

copies of each gene. An individual can have two copies of the same

allele or two different alleles. We can call the frequency of one allele

p and the frequency of the other q. The Wright–Fisher model (named after Sewall Wright and Ronald Fisher) assumes that generations do not overlap (for example, annual plants

have exactly one generation per year) and that each copy of the gene

found in the new generation is drawn independently at random from all

copies of the gene in the old generation. The formula to calculate the

probability of obtaining k copies of an allele that had frequency p in the last generation is then

where the symbol "!" signifies the factorial function. This expression can also be formulated using the binomial coefficient,

Moran model

The Moran model

assumes overlapping generations. At each time step, one individual is

chosen to reproduce and one individual is chosen to die. So in each

timestep, the number of copies of a given allele can go up by one, go

down by one, or can stay the same. This means that the transition matrix is tridiagonal, which means that mathematical solutions are easier for the Moran model than for the Wright–Fisher model. On the other hand, computer simulations

are usually easier to perform using the Wright–Fisher model, because

fewer time steps need to be calculated. In the Moran model, it takes N timesteps to get through one generation, where N is the effective population size. In the Wright–Fisher model, it takes just one.

In practice, the Moran and Wright–Fisher models give

qualitatively similar results, but genetic drift runs twice as fast in

the Moran model.

Other models of drift

If

the variance in the number of offspring is much greater than that given

by the binomial distribution assumed by the Wright–Fisher model, then

given the same overall speed of genetic drift (the variance effective

population size), genetic drift is a less powerful force compared to

selection. Even for the same variance, if higher moments

of the offspring number distribution exceed those of the binomial

distribution then again the force of genetic drift is substantially

weakened.

Random effects other than sampling error

Random changes in allele frequencies can also be caused by effects other than sampling error, for example random changes in selection pressure.

One important alternative source of stochasticity, perhaps more important than genetic drift, is genetic draft. Genetic draft is the effect on a locus by selection on linked loci. The mathematical properties of genetic draft are different from those of genetic drift. The direction of the random change in allele frequency is autocorrelated across generations.

Drift and fixation

The Hardy–Weinberg principle

states that within sufficiently large populations, the allele

frequencies remain constant from one generation to the next unless the

equilibrium is disturbed by migration, genetic mutations, or selection.

However, in finite populations, no new alleles are gained from

the random sampling of alleles passed to the next generation, but the

sampling can cause an existing allele to disappear. Because random sampling

can remove, but not replace, an allele, and because random declines or

increases in allele frequency influence expected allele distributions

for the next generation, genetic drift drives a population towards

genetic uniformity over time. When an allele reaches a frequency of 1

(100%) it is said to be "fixed" in the population and when an allele

reaches a frequency of 0 (0%) it is lost. Smaller populations achieve

fixation faster, whereas in the limit of an infinite population,

fixation is not achieved. Once an allele becomes fixed, genetic drift

comes to a halt, and the allele frequency cannot change unless a new

allele is introduced in the population via mutation or gene flow. Thus even while genetic drift is a random, directionless process, it acts to eliminate genetic variation over time.

Rate of allele frequency change due to drift

Ten

simulations of random genetic drift of a single given allele with an

initial frequency distribution 0.5 measured over the course of 50

generations, repeated in three reproductively synchronous populations of

different sizes. In these simulations, alleles drift to loss or

fixation (frequency of 0.0 or 1.0) only in the smallest population.

Assuming genetic drift is the only evolutionary force acting on an allele, after t generations in many replicated populations, starting with allele frequencies of p and q, the variance in allele frequency across those populations is

Time to fixation or loss

Assuming

genetic drift is the only evolutionary force acting on an allele, at

any given time the probability that an allele will eventually become

fixed in the population is simply its frequency in the population at

that time. For example, if the frequency p for allele A is 75% and the frequency q for allele B is 25%, then given unlimited time the probability A will ultimately become fixed in the population is 75% and the probability that B will become fixed is 25%.

The expected number of generations for fixation to occur is proportional to the population size, such that fixation is predicted to occur much more rapidly in smaller populations.

Normally the effective population size, which is smaller than the total

population, is used to determine these probabilities. The effective

population (Ne) takes into account factors such as the level of inbreeding,

the stage of the lifecycle in which the population is the smallest, and

the fact that some neutral genes are genetically linked to others that

are under selection. The effective population size may not be the same for every gene in the same population.

One forward-looking formula used for approximating the expected

time before a neutral allele becomes fixed through genetic drift,

according to the Wright–Fisher model, is

where T is the number of generations, Ne is the effective population size, and p is the initial frequency for the given allele. The result is the number of generations expected to pass before fixation occurs for a given allele in a population with given size (Ne) and allele frequency (p).

The expected time for the neutral allele to be lost through genetic drift can be calculated as

When a mutation appears only once in a population large enough for

the initial frequency to be negligible, the formulas can be simplified

to

for average number of generations expected before fixation of a neutral mutation, and

for the average number of generations expected before the loss of a neutral mutation.

Time to loss with both drift and mutation

The

formulae above apply to an allele that is already present in a

population, and which is subject to neither mutation nor natural

selection. If an allele is lost by mutation much more often than it is

gained by mutation, then mutation, as well as drift, may influence the

time to loss. If the allele prone to mutational loss begins as fixed in

the population, and is lost by mutation at rate m per replication, then

the expected time in generations until its loss in a haploid population

is given by

![{\displaystyle {\bar {T}}_{\text{lost}}\approx {\begin{cases}{\dfrac {1}{m}},{\text{ if }}mN_{e}\ll 1\\[8pt]{\dfrac {\ln {(mN_{e})}+\gamma }{m}}{\text{ if }}mN_{e}\gg 1\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0dca9b7dc746a7b2a8d8a63770ac53782d1639e3)

where  is Euler's constant.

The first approximation represents the waiting time until the first

mutant destined for loss, with loss then occurring relatively rapidly by

genetic drift, taking time Ne ≪ 1/m.

The second approximation represents the time needed for deterministic

loss by mutation accumulation. In both cases, the time to fixation is

dominated by mutation via the term 1/m, and is less affected by the effective population size.

is Euler's constant.

The first approximation represents the waiting time until the first

mutant destined for loss, with loss then occurring relatively rapidly by

genetic drift, taking time Ne ≪ 1/m.

The second approximation represents the time needed for deterministic

loss by mutation accumulation. In both cases, the time to fixation is

dominated by mutation via the term 1/m, and is less affected by the effective population size.

Versus natural selection

In

natural populations, genetic drift and natural selection do not act in

isolation; both phenomena are always at play, together with mutation and

migration. Neutral evolution is the product of both mutation and drift,

not of drift alone. Similarly, even when selection overwhelms genetic

drift, it can only act on variation that mutation provides.

While natural selection has a direction, guiding evolution towards heritable adaptations to the current environment, genetic drift has no direction and is guided only by the mathematics of chance. As a result, drift acts upon the genotypic frequencies

within a population without regard to their phenotypic effects. In

contrast, selection favors the spread of alleles whose phenotypic

effects increase survival and/or reproduction of their carriers, lowers

the frequencies of alleles that cause unfavorable traits, and ignores

those that are neutral.

The law of large numbers predicts that when the absolute number of copies of the allele is small (e.g., in small populations),

the magnitude of drift on allele frequencies per generation is larger.

The magnitude of drift is large enough to overwhelm selection at any

allele frequency when the selection coefficient

is less than 1 divided by the effective population size. Non-adaptive

evolution resulting from the product of mutation and genetic drift is

therefore considered to be a consequential mechanism of evolutionary

change primarily within small, isolated populations.

The mathematics of genetic drift depend on the effective population

size, but it is not clear how this is related to the actual number of

individuals in a population. Genetic linkage

to other genes that are under selection can reduce the effective

population size experienced by a neutral allele. With a higher recombination rate, linkage decreases and with it this local effect on effective population size. This effect is visible in molecular data as a correlation between local recombination rate and genetic diversity, and negative correlation between gene density and diversity at noncoding DNA regions.

Stochasticity associated with linkage to other genes that are under

selection is not the same as sampling error, and is sometimes known as genetic draft in order to distinguish it from genetic drift.

When the allele frequency is very small, drift can also overpower

selection even in large populations. For example, while disadvantageous

mutations are usually eliminated quickly in large populations, new

advantageous mutations are almost as vulnerable to loss through genetic

drift as are neutral mutations. Not until the allele frequency for the

advantageous mutation reaches a certain threshold will genetic drift

have no effect.

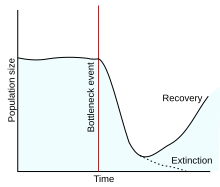

Population bottleneck

A population bottleneck is when a population contracts to a

significantly smaller size over a short period of time due to some

random environmental event. In a true population bottleneck, the odds

for survival of any member of the population are purely random, and are

not improved by any particular inherent genetic advantage. The

bottleneck can result in radical changes in allele frequencies,

completely independent of selection.

The impact of a population bottleneck can be sustained, even when

the bottleneck is caused by a one-time event such as a natural

catastrophe.

An interesting example of a bottleneck causing unusual genetic

distribution is the relatively high proportion of individuals with total

rod cell color blindness (achromatopsia) on Pingelap atoll in Micronesia.

After a bottleneck, inbreeding increases. This increases the damage

done by recessive deleterious mutations, in a process known as inbreeding depression. The worst of these mutations are selected against, leading to the loss of other alleles that are genetically linked to them, in a process of background selection. For recessive harmful mutations, this selection can be enhanced as a consequence of the bottleneck, due to genetic purging.

This leads to a further loss of genetic diversity. In addition, a

sustained reduction in population size increases the likelihood of

further allele fluctuations from drift in generations to come.

A population's genetic variation can be greatly reduced by a

bottleneck, and even beneficial adaptations may be permanently

eliminated. The loss of variation leaves the surviving population vulnerable to any new selection pressures such as disease, climatic change

or shift in the available food source, because adapting in response to

environmental changes requires sufficient genetic variation in the

population for natural selection to take place.

There have been many known cases of population bottleneck in the recent past. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, North American prairies were habitat for millions of greater prairie chickens. In Illinois

alone, their numbers plummeted from about 100 million birds in 1900 to

about 50 birds in the 1990s. The declines in population resulted from

hunting and habitat destruction, but a consequence has been a loss of

most of the species' genetic diversity. DNA

analysis comparing birds from the mid century to birds in the 1990s

documents a steep decline in the genetic variation in just the latter

few decades. Currently the greater prairie chicken is experiencing low reproductive success.

However, the genetic loss caused by bottleneck and genetic drift can increase fitness, as in Ehrlichia.

Over-hunting also caused a severe population bottleneck in the northern elephant seal in the 19th century. Their resulting decline in genetic variation can be deduced by comparing it to that of the southern elephant seal, which were not so aggressively hunted.

Founder effect

When

very few members of a population migrate to form a separate new

population, the founder effect occurs. For a period after the

foundation, the small population experiences intensive drift. In the

figure this results in fixation of the red allele.

The founder effect is a special case of a population bottleneck,

occurring when a small group in a population splinters off from the

original population and forms a new one. The random sample of alleles in

the just formed new colony is expected to grossly misrepresent the

original population in at least some respects.

It is even possible that the number of alleles for some genes in the

original population is larger than the number of gene copies in the

founders, making complete representation impossible. When a newly formed

colony is small, its founders can strongly affect the population's

genetic make-up far into the future.

A well-documented example is found in the Amish migration to Pennsylvania in 1744. Two members of the new colony shared the recessive allele for Ellis–Van Creveld syndrome.

Members of the colony and their descendants tend to be religious

isolates and remain relatively insular. As a result of many generations

of inbreeding, Ellis–Van Creveld syndrome is now much more prevalent

among the Amish than in the general population.

The difference in gene frequencies between the original population and colony may also trigger the two groups to diverge significantly over the course of many generations. As the difference, or genetic distance, increases, the two separated populations may become distinct, both genetically and phenetically,

although not only genetic drift but also natural selection, gene flow,

and mutation contribute to this divergence. This potential for

relatively rapid changes in the colony's gene frequency led most

scientists to consider the founder effect (and by extension, genetic

drift) a significant driving force in the evolution of new species. Sewall Wright was the first to attach this significance to random drift and small, newly isolated populations with his shifting balance theory of speciation. Following after Wright, Ernst Mayr

created many persuasive models to show that the decline in genetic

variation and small population size following the founder effect were

critically important for new species to develop.

However, there is much less support for this view today since the

hypothesis has been tested repeatedly through experimental research and

the results have been equivocal at best.

History

The role of random chance in evolution was first outlined by Arend L.

Hagedoorn and A. C. Hagedoorn-Vorstheuvel La Brand in 1921.

They highlighted that random survival plays a key role in the loss of

variation from populations. Fisher (1922) responded to this with the

first, albeit marginally incorrect, mathematical treatment of the

'Hagedoorn effect'.

Notably, he expected that many natural populations were too large (an N

~10,000) for the effects of drift to be substantial and thought drift

would have an insignificant effect on the evolutionary process. The

corrected mathematical treatment and term "genetic drift" was later

coined by a founder of population genetics, Sewall Wright. His first use of the term "drift" was in 1929,

though at the time he was using it in the sense of a directed process

of change, or natural selection. Random drift by means of sampling error

came to be known as the "Sewall–Wright effect," though he was never

entirely comfortable to see his name given to it. Wright referred to all

changes in allele frequency as either "steady drift" (e.g., selection)

or "random drift" (e.g., sampling error). "Drift" came to be adopted as a technical term in the stochastic sense exclusively. Today it is usually defined still more narrowly, in terms of sampling error, although this narrow definition is not universal.

Wright wrote that the "restriction of "random drift" or even "drift" to

only one component, the effects of accidents of sampling, tends to lead

to confusion."

Sewall Wright considered the process of random genetic drift by means

of sampling error equivalent to that by means of inbreeding, but later

work has shown them to be distinct.

In the early days of the modern evolutionary synthesis, scientists were beginning to blend the new science of population genetics with Charles Darwin's

theory of natural selection. Within this framework, Wright focused on

the effects of inbreeding on small relatively isolated populations. He

introduced the concept of an adaptive landscape

in which phenomena such as cross breeding and genetic drift in small

populations could push them away from adaptive peaks, which in turn

allow natural selection to push them towards new adaptive peaks.

Wright thought smaller populations were more suited for natural

selection because "inbreeding was sufficiently intense to create new

interaction systems through random drift but not intense enough to cause

random nonadaptive fixation of genes."

Wright's views on the role of genetic drift in the evolutionary

scheme were controversial almost from the very beginning. One of the

most vociferous and influential critics was colleague Ronald Fisher.

Fisher conceded genetic drift played some role in evolution, but an

insignificant one. Fisher has been accused of misunderstanding Wright's

views because in his criticisms Fisher seemed to argue Wright had

rejected selection almost entirely. To Fisher, viewing the process of

evolution as a long, steady, adaptive progression was the only way to

explain the ever-increasing complexity from simpler forms. But the

debates have continued between the "gradualists" and those who lean more

toward the Wright model of evolution where selection and drift together

play an important role.

In 1968, Motoo Kimura

rekindled the debate with his neutral theory of molecular evolution,

which claims that most of the genetic changes are caused by genetic

drift acting on neutral mutations.

The role of genetic drift by means of sampling error in evolution has been criticized by John H. Gillespie and William B. Provine, who argue that selection on linked sites is a more important stochastic force.

![{\displaystyle {\bar {T}}_{\text{lost}}\approx {\begin{cases}{\dfrac {1}{m}},{\text{ if }}mN_{e}\ll 1\\[8pt]{\dfrac {\ln {(mN_{e})}+\gamma }{m}}{\text{ if }}mN_{e}\gg 1\end{cases}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0dca9b7dc746a7b2a8d8a63770ac53782d1639e3)