Climate change scenarios or socioeconomic scenarios are projections of future greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions used by analysts to assess future vulnerability to climate change. Scenarios and pathways are created by scientists to survey any long term routes and explore the effectiveness of mitigation and helps us understand what the future may hold this will allow us to envision the future of human environment system. Producing scenarios requires estimates of future population levels, economic activity, the structure of governance, social values, and patterns of technological change. Economic and energy modelling (such as the World3 or the POLES models) can be used to analyze and quantify the effects of such drivers.

Scientists can develop separate international, regional and national climate change scenarios. These scenarios are designed to help stakeholders understand what kinds of decisions will have meaningful effects on climate change mitigation or adaptation. Most countries developing adaptation plans or Nationally Determined Contributions will commission scenario studies in order to better understand the decisions available to them.

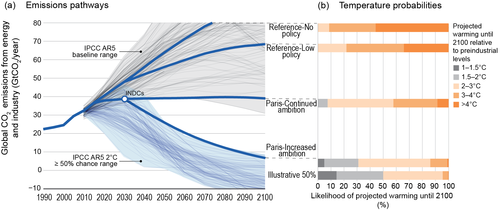

International goals for mitigating climate change through international processes like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the Paris Agreement and Sustainable Development Goal 13 ("Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts") are based on reviews of these scenarios. For example, the Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5 °C was released in 2018 order to reflect more up-to-date models of emissions, Nationally Determined Contributions, and impacts of climate change than its predecessor IPCC Fifth Assessment Report published in 2014 before the Paris Agreement.

Emissions scenarios

Global futures scenarios

These scenarios can be thought of as stories of possible futures. They allow the description of factors that are difficult to quantify, such as governance, social structures, and institutions. Morita et al. assessed the literature on global futures scenarios. They found considerable variety among scenarios, ranging from variants of sustainable development, to the collapse of social, economic, and environmental systems. In the majority of studies, the following relationships were found:

- Rising GHGs: This was associated with scenarios having a growing, post-industrial economy with globalization, mostly with low government intervention and generally high levels of competition. Income equality declined within nations, but there was no clear pattern in social equity or international income equality.

- Falling GHGs: In some of these scenarios, GDP rose. Other scenarios showed economic activity limited at an ecologically sustainable level. Scenarios with falling emissions had a high level of government intervention in the economy. The majority of scenarios showed increased social equity and income equality within and among nations.

Morita et al. (2001) noted that these relationships were not proof of causation.

No strong patterns were found in the relationship between economic activity and GHG emissions. Economic growth was found to be compatible with increasing or decreasing GHG emissions. In the latter case, emissions growth is mediated by increased energy efficiency, shifts to non-fossil energy sources, and/or shifts to a post-industrial (service-based) economy.

Factors affecting emissions growth

Development trends

In producing scenarios, an important consideration is how social and economic development will progress in developing countries. If, for example, developing countries were to follow a development pathway similar to the current industrialized countries, it could lead to a very large increase in emissions. Emissions do not only depend on the growth rate of the economy. Other factors include the structural changes in the production system, technological patterns in sectors such as energy, geographical distribution of human settlements and urban structures (this affects, for example, transportation requirements), consumption patterns (e.g., housing patterns, leisure activities, etc.), and trade patterns the degree of protectionism and the creation of regional trading blocks can affect availability to technology.

Baseline scenarios

A baseline scenario is used as a reference for comparison against an alternative scenario, e.g., a mitigation scenario. In assessing baseline scenarios literature, Fisher et al., it was found that baseline CO2 emission projections covered a large range. In the United States, electric power plants emit about 2.4 billion tons of carbon dioxide (CO2) each year, or roughly 40 percent of the nation's total emissions. The EPA has taken important first steps by setting standards that will cut the carbon pollution from automobiles and trucks nearly in half by 2025 and by proposing standards to limit the carbon pollution from new power plants.

Factors affecting these emission projections are:

- Population projections: All other factors being equal, lower population projections result in lower emissions projections.

- Economic development: Economic activity is a dominant driver of energy demand and thus of GHG emissions.

- Energy use: Future changes in energy systems are a fundamental determinant of future GHG emissions.

- Energy intensity: This is the total primary energy supply (TPES) per unit of GDP. In all of the baseline scenarios assessments, energy intensity was projected to improve significantly over the 21st century. The uncertainty range in projected energy intensity was large (Fisher et al. 2007).

- Carbon intensity: This is the CO2 emissions per unit of TPES. Compared with other scenarios, Fisher et al. (2007) found that the carbon intensity was more constant in scenarios where no climate policy had been assumed. The uncertainty range in projected carbon intensity was large. At the high end of the range, some scenarios contained the projection that energy technologies without CO2 emissions would become competitive without climate policy. These projections were based on the assumption of increasing fossil fuel prices and rapid technological progress in carbon-free technologies. Scenarios with a low improvement in carbon intensity coincided with scenarios that had a large fossil fuel base, less resistance to coal consumption, or lower technology development rates for fossil-free technologies.

- Land-use change: Land-use change plays an important role in climate change, impacting on emissions, sequestration and albedo. One of the dominant drivers in land-use change is food demand. Population and economic growth are the most significant drivers of food demand.

Quantitative emissions projections

A wide range of quantitative projections of greenhouse gas emissions have been produced. The "SRES" scenarios are "baseline" emissions scenarios (i.e., they assume that no future efforts are made to limit emissions), and have been frequently used in the scientific literature (see Special Report on Emissions Scenarios for details). Greenhouse gas#Projections summarizes projections out to 2030, as assessed by Rogner et al. Other studies are presented here.

Individual studies

In the reference scenario of World Energy Outlook 2004, the International Energy Agency projected future energy-related CO2 emissions. Emissions were projected to increase by 62% between the years 2002 and 2030. This lies between the SRES A1 and B2 scenario estimates of +101% and +55%, respectively. As part of the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report, Sims et al. (2007) compared several baseline and mitigation scenarios out to the year 2030. The baseline scenarios included the reference scenario of IEA's World Energy Outlook 2006 (WEO 2006), SRES A1, SRES B2, and the ABARE reference scenario. Mitigation scenarios included the WEO 2006 Alternative policy, ABARE Global Technology and ABARE Global Technology + CCS. Projected total energy-related emissions in 2030 (measured in GtCO2-eq) were 40.4 for the IEA WEO 2006 reference scenario, 58.3 for the ABARE reference scenario, 52.6 for the SRES A1 scenario, and 37.5 for the SRES B2 scenario. Emissions for the mitigation scenarios were 34.1 for the IEA WEO 2006 Alternative Policy scenario, 51.7 for the ABARE Global Technology scenario, and 49.5 for the ABARE Global Technology + CCS scenario.

Garnaut et al. (2008) made a projection of fossil-fuel CO2 emissions for the time period 2005-2030. Their "business-as usual" annual projected growth rate was 3.1% for this period. This compares to 2.5% for the fossil-fuel intensive SRES A1FI emissions scenario, 2.0% for the SRES median scenario (defined by Garnaut et al. (2008) as the median for each variable and each decade of the four SRES marker scenarios), and 1.6% for the SRES B1 scenario. Garnaut et al. (2008) also referred to projections over the same time period of the: US Climate Change Science Program (2.7% max, and 2.0% mean), International Monetary Fund's 2007 World Economic Outlook (2.5%), Energy Modelling Forum (2.4% max, 1.7% mean), US Energy Information Administration (2.2% high, 1.8% medium, and 1.4% low), IEA's World Energy Outlook 2007 (2.1% high, 1.8 base case), and the base case from the Nordhaus model (1.3%).

The central scenario of the International Energy Agency publication World Energy Outlook 2011 projects a continued increase in global energy-related CO

2 emissions, with emissions reaching 36.4 Gt in the year 2035. This is a 20% increase in emissions relative to the 2010 level.

UNEP 2011 synthesis report

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP, 2011) looked at how world emissions might develop out to the year 2020 depending on different policy decisions. To produce their report, UNEP (2011) convened 55 scientists and experts from 28 scientific groups across 15 countries.

Projections, assuming no new efforts to reduce emissions or based on the "business-as-usual" hypothetical trend, suggested global emissions in 2020 of 56 gigatonnes CO

2-equivalent (GtCO

2-eq), with a range of 55-59 GtCO

2-eq. In adopting a different baseline where the pledges to the Copenhagen Accord were met in their most ambitious form, the projected global emission by 2020 will still reach the 50 gigatonnes CO

2. Continuing with the current trend, particularly in the case of low-ambition form, there is an expectation of 3°

Celsius temperature increase by the end of the century, which is

estimated to bring severe environmental, economic, and social

consequences. For instance, warmer air temperature and the resulting evapotranspiration can lead to larger thunderstorms and greater risk from flash flooding.

Other projections considered the effect on emissions of policies

put forward by UNFCCC Parties to address climate change. Assuming more

stringent efforts to limit emissions lead to projected global emissions

in 2020 of between 49-52 GtCO

2-eq, with a median estimate of 51 GtCO

2-eq. Assuming less stringent efforts to limit emissions lead to projected global emissions in 2020 of between 53-57 GtCO

2-eq, with a median estimate of 55 GtCO

2-eq.

National climate (change) projections

National climate (change) projections (also termed "national climate scenarios" or "national climate assessments") are specialized regional climate projections, typically produced for and by individual countries. What distinguishes national climate projections from other climate projections is that they are officially signed off by the national government, thereby being the relevant national basis for adaptation planning. Climate projections are commonly produced over several years by countries' national meteorological services or academic institutions working on climate change.

Typically distributed as a single product, climate projections condense information from multiple climate models, using multiple greenhouse gas emission pathways (e.g. Representative Concentration Pathways) to characterize different yet coherent climate futures. Such a product highlights plausible climatic changes through the use of narratives, graphs, maps, and perhaps raw data. Climate projections are often publicly available for policy-makers, public and private decision makers, as well as researchers to undertake further climate impact studies, risk assessments, and climate change adaptation research. The projections are updated every few years, in order to incorporate new scientific insights and improved climate models.

Aims

National climate projections illustrate plausible changes to a country's climate in the future. By using multiple emission scenarios, these projections highlight the impact different global mitigation efforts have on variables, including temperature, precipitation, and sunshine hours. Climate scientists strongly recommend the use of multiple emission scenarios in order to ensure that decisions are robust to a range of climatic changes. National climate projections form the basis of national climate adaptation and climate resilience plans, which are reported to UNFCCC and used in IPCC assessments.

Design

To explore a wide range of plausible climatic outcomes and to enhance confidence in the projections, national climate change projections are often generated from multiple general circulation models (GCMs). Such climate ensembles can take the form of perturbed physics ensembles (PPE), multi-model ensembles (MME), or initial condition ensembles (ICE). As the spatial resolution of the underlying GCMs is typically quite coarse, the projections are often downscaled, either dynamically using regional climate models (RCMs), or statistically. Some projections include data from areas which are larger than the national boundaries, e.g. to more fully evaluate catchment areas of transboundary rivers. Some countries have also produced more localized projections for smaller administrative areas, e.g. States in the United States, and Länder in Germany.

Various countries have produced their national climate projections with feedback and/or interaction with stakeholders. Such engagement efforts have helped tailoring the climate information to the stakeholders' needs, including the provision of sector-specific climate indicators such as degree-heating days. In the past, engagement formats have included surveys, interviews, presentations, workshops, and use-cases. While such interactions helped not only to enhance the usability of the climate information, it also fostered discussions on how to use climate information in adaptation projects. Interestingly, a comparison of the British, Dutch, and Swiss climate projections revealed distinct national preferences in the way stakeholders were engaged, as well as how the climate model outputs were condensed and communicated.

Examples

Over 30 countries have reported national climate projections / scenarios in their most recent National Communications to United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Many European governments have also funded national information portals on climate change.

- Australia: CCIA

- California: Cal-Adapt

- Netherlands: KNMI'14

- Switzerland: CH2011 / CH2018

- UK: UKCP09 / UKCP18

For countries which lack adequate resources to develop their own climate change projections, organisations such as UNDP or FAO have sponsored development of projections and national adaptation programmes (NAPAs).

Applications

National climate projections are widely used to predict climate change impacts in a wide range of economic sectors, and also to inform climate change adaptation studies and decisions. Some examples include:

- Energy

- Water

- Agriculture and forestry: effects of climate change on agriculture

- Fisheries

- Ecosystems and Biodiversity: effects of climate change on oceans, effects of climate change on terrestrial animals, effects of climate change on plant biodiversity

- Health: effects of climate change on human health

- Transport

- Coastal areas

- Tourism

- Insurance

- Infrastructure

- Cities and urban environments

- Disaster risk

- Human migration (across many nations and relevant to nations' border control, migration policies and climate adaptation)

Comparisons

A detailed comparison between some national climate projections have been carried out.

Global long-term scenarios

In 2021, researchers who found that projecting effects of greenhouse gas emissions only for up to 2100, as widely practiced in research and policy-making, is short-sighted modeled RCPs climate change scenarios and their effects for up to 2500.

Being able to reduce greenhouse gas emissions will require many major transitions: including massive reduction of fossil fuels, producing and distributing low-emission energy sources, changing to various other energy providers, and, maybe most important, conserving energy and being more efficient with it. If fossil fuels continue to be burnt and vented to the environment, GHG emissions will be very hard to reduce.

Mitigation scenarios

Climate change mitigation scenarios are possible futures in which global warming is reduced by deliberate actions, such as a comprehensive switch to energy sources other than fossil fuels. These are actions that minimize emissions so atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations are stabilized at levels that restrict the adverse consequences of climate change. Using these scenarios, the examination of the impacts of different carbon prices on an economy is enabled within the framework of different levels of global aspirations.

A typical mitigation scenario is constructed by selecting a long-range target, such as a desired atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (CO2), and then fitting the actions to the target, for example by placing a cap on net global and national emissions of greenhouse gases.

An increase of global temperature by more than 2 °C has come to be the majority definition of what would constitute intolerably dangerous climate change with efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels per the Paris Agreement. Some climate scientists are increasingly of the opinion that the goal should be a complete restoration of the atmosphere's preindustrial condition, on the grounds that too protracted a deviation from those conditions will produce irreversible changes.

Stabilization wedges

A stabilization wedge (or simply "wedge") is an action which incrementally reduces projected emissions. The name is derived from the triangular shape of the gap between reduced and unreduced emissions trajectories when graphed over time. For example, a reduction in electricity demand due to increased efficiency means that less electricity needs to be generated and thus fewer emissions need to be produced. The term originates in the Stabilization Wedge Game. As a reference unit, a stabilization wedge is equal to the following examples of mitigation initiatives: deployment of two hundred thousand 10 MW wind turbines; completely halting the deforestation and planting of 300 million hectares of trees; the increase in the average energy efficiency of all the world's buildings by 25 percent; or the installation of carbon capture and storage facilities in 800 large coal-fired power plants. Pacala and Socolow proposed in their work, Stabilization Wedges, that seven wedges are required to be delivered by 2050 – at current technologies – to make a significant impact on the mitigation of climate change. There are, however, sources that estimate the need for 14 wedges because Pacala and Socolow's proposal would only stabilize carbon dioxide emissions at current levels but not the atmospheric concentration, which is increasing by more than 2 ppm/year. In 2011, Socolow revised their earlier estimate to nine.

Target levels of CO2

Contributions to climate change, whether they cool or warm the Earth, are often described in terms of the radiative forcing or imbalance they introduce to the planet's energy budget. Now and in the future, anthropogenic carbon dioxide is believed to be the major component of this forcing, and the contribution of other components is often quantified in terms of "parts-per-million carbon dioxide equivalent" (ppm CO2e), or the increment/decrement in carbon dioxide concentrations which would create a radiative forcing of the same magnitude.

450 ppm

The BLUE scenarios in the IEA's Energy Technology Perspectives publication of 2008 describe pathways to a long-range concentration of 450 ppm. Joseph Romm has sketched how to achieve this target through the application of 14 wedges.

World Energy Outlook 2008, mentioned above, also describes a "450 Policy Scenario", in which extra energy investments to 2030 amount to $9.3 trillion over the Reference Scenario. The scenario also features, after 2020, the participation of major economies such as China and India in a global cap-and-trade scheme initially operating in OECD and European Union countries. Also the less conservative 450 ppm scenario calls for extensive deployment of negative emissions, i.e. the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and OECD, "Achieving lower concentration targets (450 ppm) depends significantly on the use of BECCS".

550 ppm

This is the target advocated (as an upper bound) in the Stern Review. As approximately a doubling of CO2 levels relative to preindustrial times, it implies a temperature increase of about three degrees, according to conventional estimates of climate sensitivity. Pacala and Socolow list 15 "wedges", any 7 of which in combination should suffice to keep CO2 levels below 550 ppm.

The International Energy Agency's World Energy Outlook report for 2008 describes a "Reference Scenario" for the world's energy future "which assumes no new government policies beyond those already adopted by mid-2008", and then a "550 Policy Scenario" in which further policies are adopted, a mixture of "cap-and-trade systems, sectoral agreements and national measures". In the Reference Scenario, between 2006 and 2030 the world invests $26.3 trillion in energy-supply infrastructure; in the 550 Policy Scenario, a further $4.1 trillion is spent in this period, mostly on efficiency increases which deliver fuel cost savings of over $7 trillion.

Other greenhouse gases

Greenhouse gas concentrations are aggregated in terms of carbon dioxide equivalent. Some multi-gas mitigation scenarios have been modeled by Meinshausen et al.

As a short-term focus

In a 2000 paper, Hansen argued that the 0.75 °C rise in average global temperatures over the last 100 years has been driven mainly by greenhouse gases other than carbon dioxide, since warming due to CO2 had been offset by cooling due to aerosols, implying the viability of a strategy initially based around reducing emissions of non-CO2 greenhouse gases and of black carbon, focusing on CO2 only in the longer run.

This was also argued by Veerabhadran Ramanathan and Jessica Seddon Wallack in the September/October 2009 Foreign Affairs.