From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The fall of Saigon, also known as the Liberation of Saigon or Liberation of the South by the Vietnamese government, and known as Black April by anti-communist overseas Vietnamese was the capture of Saigon, the capital of South Vietnam, by the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (Viet Cong) on 30 April 1975. The event marked the end of the Vietnam War and the start of a transition period from the formal reunification of Vietnam into the Socialist Republic of Vietnam.

The PAVN, under the command of General Văn Tiến Dũng, began their final attack on Saigon on 29 April 1975, with the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) forces commanded by General Nguyễn Văn Toàn

suffering a heavy artillery bombardment. By the afternoon of the next

day, the PAVN and the Viet Cong had occupied the important points of the

city and raised their flag over the South Vietnamese presidential palace.

The capture of the city was preceded by Operation Frequent Wind,

the evacuation of almost all American civilian and military personnel

in Saigon, along with tens of thousands of South Vietnamese civilians

who had been associated with the Republic of Vietnam regime. A few

Americans chose not to be evacuated. United States ground combat units

had left South Vietnam more than two years prior to the fall of Saigon

and were not available to assist with either the defense of Saigon or

the evacuation. The evacuation was the largest helicopter evacuation in history.

In addition to the flight of refugees, the end of the war and the

institution of new rules by the communist government contributed to a

decline in the city's population until 1979, after which the population increased again.

On 3 July 1976, the National Assembly of the unified Vietnam renamed Saigon in honor of Hồ Chí Minh, the late Chairman of the Workers' Party of Vietnam and founder of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam).

Names

Various names have been applied to these events. The Vietnamese government officially calls it the "Day of liberating the South for national reunification" (Vietnamese: Giải phóng miền Nam, thống nhất đất nước) or "Liberation Day" (Ngày Giải Phóng), but the term "Fall of Saigon" is commonly used in Western accounts. It is called the "Ngày mất nước" (Day we Lost the Country), "Tháng Tư Đen" (Black April), "National Day of Shame" (Ngày Quốc Nhục) or "National Day of Resentment" (Ngày Quốc Hận) by many Overseas Vietnamese who were refugees from communism.

In Vietnamese, it is also known by the neutral name "April 30, 1975 incident" (Sự kiện 30 tháng 4 năm 1975) or simply "April 30" (30 tháng 4).

North Vietnamese advance

Situation of South Vietnam before the capture of Saigon (lower right) on 30 April 1975

The rapidity with which the South Vietnamese position collapsed in

1975 was surprising to most American and South Vietnamese observers, and

probably to the North Vietnamese and their allies as well. For

instance, a memo prepared by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and U.S. Army Intelligence, published on 5 March, indicated that South Vietnam could hold out through the current dry season—i.e., at least until 1976.

These predictions proved to be grievously in error. Even as that memo

was being released, General Dũng was preparing a major offensive in the Central Highlands of Vietnam, which began on 10 March and led to the capture of Buôn Ma Thuột.

The ARVN began a disorderly and costly retreat, hoping to redeploy its

forces and hold the southern part of South Vietnam, south of the 13th parallel.

Supported by artillery and armor, the PAVN continued to march

towards Saigon, capturing the major cities of northern South Vietnam at

the end of March—Huế on the 25th and Đà Nẵng

on the 28th. Along the way, disorderly South Vietnamese retreats and

the flight of refugees—there were more than 300,000 in Đà Nẵng—damaged

South Vietnamese prospects for a turnaround. After the loss of Đà Nẵng,

those prospects had already been dismissed as nonexistent by American

CIA officers in Vietnam, who believed that nothing short of B-52 strikes against Hanoi could possibly stop the North Vietnamese.

By 8 April, the North Vietnamese Politburo,

which in March had recommended caution to Dũng, cabled him to demand

"unremitting vigor in the attack all the way to the heart of Saigon." On 14 April, they renamed the campaign the "Hồ Chí Minh campaign", after revolutionary leader Hồ Chí Minh, in hopes of wrapping it up before his birthday on 19 May.

Meanwhile, South Vietnam failed to garner any significant increase in

military aid from the United States, snuffing out President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu's hopes for renewed American support.

On 9 April, PAVN forces reached Xuân Lộc, the last line of defense before Saigon, where the ARVN 18th Division made a last stand

and held the city through fierce fighting for 11 days. The ARVN finally

withdrew from Xuân Lộc on 20 April having inflicted heavy losses on the

PAVN, and President Thiệu resigned on 21 April in a tearful televised

announcement in which he denounced the United States for failing to come

to the aid of the South. The North Vietnamese front line was now just 26 miles (42 km) from downtown Saigon. The victory at Xuân Lộc, which had drawn many South Vietnamese troops away from the Mekong Delta area,

opened the way for PAVN to encircle Saigon, and they soon did so,

moving 100,000 troops in position around the city by 27 April. With the

ARVN having few defenders, the fate of the city was effectively sealed.

The ARVN III Corps commander, General Toàn,

had organized five centers of resistance to defend the city. These

fronts were so connected as to form an arc enveloping the entire area

west, north, and east of the capital. The Cu Chi front, to the northwest, was defended by the 25th Division; the Binh Duong front, to the north, was the responsibility of the 5th Division; the Bien Hoa front, to the northeast, was defended by the 18th Division; the Vung Tau and 15 Route front, to the southeast, were held by the 1st Airborne Brigade and one battalion of the 3rd Division; and the Long An front, for which the Capital Military District Command was responsible, was defended by elements of the re-formed 22nd Division. South Vietnamese defensive forces around Saigon totalled approximately 60,000 troops.

However, as the exodus made it into Saigon, along with them were many

ARVN soldiers, which swelled the "men under arms" in the city to over

250,000. These units were mostly battered and leaderless, which threw

the city into further anarchy.

Evacuation

The

rapid PAVN advances of March and early April led to increased concern

in Saigon that the city, which had been fairly peaceful throughout the

war and whose people had endured relatively little suffering, was soon

to come under direct attack.

Many feared that once the communists took control of the city, a

bloodbath of reprisals would take place. In 1968, PAVN and VC forces had

occupied Huế for close to a month. After the communists were repelled, American and ARVN forces had found mass graves. A study indicated that the VC had targeted ARVN officers, Roman Catholics, intellectuals, businessmen, and other suspected counterrevolutionaries.

More recently, eight Americans captured in Buôn Ma Thuột had vanished

and reports of beheadings and other executions were filtering through

from Huế and Đà Nẵng, mostly spurred on by government propaganda.

Most Americans and citizens of other countries allied to the United

States wanted to evacuate the city before it fell, and many South

Vietnamese, especially those associated with the United States or South

Vietnamese government, wanted to leave as well.

As early as the end of March, some Americans were leaving the city. Flights out of Saigon, lightly booked under ordinary circumstances, were full. Throughout April the speed of the evacuation increased, as the Defense Attaché Office

(DAO) began to fly out nonessential personnel. Many Americans attached

to the DAO refused to leave without their Vietnamese friends and

dependents, who included common-law wives and children. It was illegal

for the DAO to move these people to American soil, and this initially

slowed down the rate of departure, but eventually the DAO began

illegally flying undocumented Vietnamese to Clark Air Base in the Philippines.

On 3 April, President Gerald Ford announced "Operation Babylift", which would evacuate about 2,000 orphans from the country. One of the Lockheed C-5 Galaxy planes involved in the operation crashed, killing 155 passengers and crew and seriously reducing the morale of the American staff. In addition to the over 2,500 orphans evacuated by Babylift, Operation New Life

resulted in the evacuation of over 110,000 Vietnamese refugees. The

final evacuation was Operation Frequent Wind which resulted in 7,000

people being evacuated from Saigon by helicopter.

American administration plans for final evacuation

By

this time the Ford administration had also begun planning a complete

evacuation of the American presence. The planning was complicated by

practical, legal, and strategic concerns. The administration was divided

on how swift the evacuations should be. The Pentagon sought to evacuate as fast as possible, to avoid the risk of casualties or other accidents. The U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam, Graham Martin,

was technically the field commander for any evacuation since

evacuations are part of the purview of the State Department. Martin drew

the ire of many in the Pentagon by wishing to keep the evacuation

process as quiet and orderly as possible. His desire for this was to

prevent total chaos and to deflect the real possibility of South

Vietnamese turning against Americans and to keep all-out bloodshed from

occurring.

Ford approved a plan between the extremes in which all but 1,250

Americans—few enough to be removed in a single day's helicopter

airlift—would be evacuated quickly; the remaining 1,250 would leave only

when the airport was threatened. In between, as many Vietnamese

refugees as possible would be flown out.

American evacuation planning was set against other administration

policies. Ford still hoped to gain additional military aid for South

Vietnam. Throughout April, he attempted to get Congress behind a

proposed appropriation of $722 million, which might allow for the

reconstitution of some of the South Vietnamese forces that had been

destroyed. National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger

was opposed to a full-scale evacuation as long as the aid option

remained on the table because the removal of American forces would

signal a loss of faith in Thiệu and severely weaken him.

There was also a concern in the administration over whether the

use of military forces to support and carry out the evacuation was

permitted under the newly passed War Powers Act. Eventually White House

lawyers determined that the use of American forces to rescue citizens

in an emergency was unlikely to run afoul of the law, but the legality

of using military assets to withdraw refugees was unknown.

Refugees

While

American citizens were generally assured of a simple way to leave the

country just by showing up to an evacuation point, South Vietnamese who

wanted to leave Saigon before it fell often resorted to independent

arrangements. The under-the-table payments required to gain a passport

and exit visa jumped sixfold, and the price of seagoing vessels tripled.

Those who owned property in the city were often forced to sell it at a

substantial loss or abandon it altogether; the asking price of one

particularly impressive house was cut 75 percent within a two-week

period. American visas

were of enormous value, and Vietnamese seeking American sponsors posted

advertisements in newspapers. One such ad read: "Seeking adoptive

parents. Poor diligent students" followed by names, birthdates, and

identity card numbers.

A disproportionate fraction of Vietnamese in the 1975 wave of

emigration who later achieved refugee status in the United States were

former members of the South Vietnamese government and military. Though

most expected to find political and personal freedom in the United

States on account of their anti-Communist bonafides, many were placed in

U.S. military detention centers for weeks to months.

Political movements and attempts at a negotiated solution

As

the North Vietnamese chipped away more and more at South Vietnam,

internal opposition to President Thiệu continued to accumulate. For

instance, in early April, the Senate unanimously voted through a call

for new leadership, and some top military commanders were pressing for a

coup. In response to this pressure, Thiệu made some changes to his

cabinet, and Prime Minister Trần Thiện Khiêm resigned. This did little to reduce the opposition to Thiệu. On 8 April, a South Vietnamese pilot and communist, Nguyễn Thành Trung, bombed the Independence Palace and then flew to a PAVN-controlled airstrip; Thiệu was not hurt.

Many in the American mission—Martin in particular—along with some

key figures in Washington, believed that negotiations with the

communists were still possible, especially if Saigon could stabilize the

military situation. Ambassador Martin's hope was that North Vietnam's

leaders would be willing to allow a "phased withdrawal" whereby a

gradual departure might be achieved in order to allow helpful locals and

all Americans to leave (along with full military withdrawal) over a

period of months.

Opinions were divided on whether any government headed by Thiệu could effect such a political solution. The foreign minister of the Provisional Revolutionary Government

(PRG) had indicated, on 2 April, that the PRG might negotiate with a

Saigon government that did not include Thiệu. Thus, even among Thiệu's

supporters, pressure was growing for his ouster.

President Thiệu resigned on 21 April. His remarks were

particularly hard on the Americans, first for forcing South Vietnam to

accede to the Paris Peace Accords,

second for failing to support South Vietnam afterwards, and all the

while asking South Vietnam "to do an impossible thing, like filling up

the oceans with stones." The presidency was turned over to Vice President Trần Văn Hương.

The view of the North Vietnamese government, broadcast by Radio Hanoi,

was that the new regime was merely "another puppet regime."

Last days

- All times given are Saigon time.

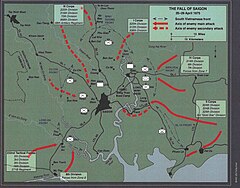

PAVN encirclement

Map showing PAVN encirclement of Saigon

On 27 April, Saigon was hit by PAVN rockets—the first in more than 40 months.

With his overtures to the North rebuffed out of hand, Tran resigned on 28 April and was succeeded by General Duong Van Minh.

Minh took over a regime that was by this time in a state of utter

collapse. He had longstanding ties with the Communists, and it was hoped

he could negotiate a ceasefire; however, Hanoi was in no mood to

negotiate. On 28 April, PAVN forces fought their way into the outskirts

of the city. At the Newport Bridge (Cầu Tân Cảng), about five kilometres (three miles) from the city centre, the VC seized the Thảo Điền area at the eastern end of the bridge and attempted to seize the bridge but were repulsed by the ARVN 12th Airborne Battalion.

As Bien Hoa was falling, General Toan fled to Saigon, informing the

government that most of the top ARVN leadership had virtually resigned

themselves to defeat.

At 18:06 on 28 April, as President Minh finished his acceptance speech three A-37 Dragonflies piloted by former Republic of Vietnam Air Force (RVNAF) pilots, who had defected to the Vietnamese People's Air Force at the fall of Da Nang, dropped six Mk81 250 lb bombs on Tan Son Nhut Air Base damaging aircraft. RVNAF F-5s took off in pursuit, but they were unable to intercept the A-37s.[56]: 70 C-130s leaving Tan Son Nhut reported receiving PAVN .51 cal

and 37 mm anti-aircraft (AAA) fire while sporadic PAVN rocket and

artillery attacks also started to hit the airport and air base. C-130 flights were stopped temporarily after the air attack but resumed at 20:00 on 28 April.

At 03:58 on 29 April, C-130E, #72-1297, flown by a crew from the 776th Tactical Airlift Squadron, was destroyed by a 122 mm rocket while taxiing to pick up refugees after offloading a BLU-82

at the base. The crew evacuated the burning aircraft on the taxiway and

departed the airfield on another C-130 that had previously landed. This was the last USAF fixed-wing aircraft to leave Tan Son Nhat.

At dawn on 29 April the RVNAF began to haphazardly depart Tan Son Nhut Air Base as A-37s, F-5s, C-7s, C-119s and C-130s departed for Thailand while UH-1s took off in search of the ships of Task Force 76. Some RVNAF aircraft stayed to continue to fight the advancing PAVN. One AC-119 gunship had spent the night of 28/29 April dropping flares and firing on the approaching PAVN. At dawn on 29 April, two A-1 Skyraiders began patrolling the perimeter of Tan Son Nhut at 2,500 feet (760 m) until one was shot down, presumably by an SA-7

missile. At 07:00 the AC-119 was firing on PAVN to the east of Tan Son

Nhut when it too was hit by an SA-7 and fell in flames to the ground.

At 06:00 on 29 April, General Dũng was ordered by the Politburo

to "strike with the greatest determination straight into the enemy's

final lair." After one day of bombardment and general offensive, the PAVN were ready to make their final push into the city.

At 08:00 on 29 April Lieutenant General Trần Văn Minh, commander of the RVNAF and 30 of his staff arrived at the DAO Compound demanding evacuation, signifying the complete loss of RVNAF command and control.

Operation Frequent Wind

A U.S. Marine provides security as American helicopters land at the DAO compound

South Vietnamese refugees arrive on a U.S. Navy vessel during Operation Frequent Wind

The continuing rocket fire and debris on the runways at Tan Son Nhut caused General Homer D. Smith,

the U.S. defense attaché in Saigon, to advise Ambassador Martin that

the runways were unfit for use and that the emergency evacuation of

Saigon would need to be completed by helicopter.

Originally, Ambassador Martin had intended to effect the evacuation by

use of fixed-wing aircraft from the base. This plan was altered at a

critical time when a South Vietnamese pilot decided to defect, and

jettisoned his ordnance along the only runways still in use (which had

not yet been destroyed by shelling).

Under pressure from Kissinger, Martin forced Marine guards to

take him to Tan Son Nhat in the midst of continued shelling, so he might

personally assess the situation. After seeing that fixed-wing

departures were not an option (a decision Martin did not want to make

without firsthand knowledge of the situation on the ground, in case the

helicopter lift failed), Martin gave the green light for the helicopter

evacuation to begin in earnest.

Reports came in from the outskirts of the city that the PAVN were closing in. At 10:48, Martin relayed to Kissinger his desire to activate Operation Frequent Wind, the helicopter evacuation of U.S. personnel and at-risk Vietnamese. At 10:51 on 29 April, the order was given by CINCPAC to commence Operation Frequent Wind. The American radio station began regular play of Irving Berlin's "White Christmas", the signal for American personnel to move immediately to the evacuation points.

Under this plan, CH-53 and CH-46 helicopters were used to evacuate Americans and friendly Vietnamese to ships, including the Seventh Fleet,

in the South China Sea. The main evacuation point was the DAO Compound

at Tan Son Nhat; buses moved through the city picking up passengers and

driving them out to the airport, with the first buses arriving at Tan

Son Nhat shortly after noon. The first CH-53 landed at the DAO compound

in the afternoon, and by the evening, 395 Americans and more than 4,000

Vietnamese had been evacuated. By 23:00 the U.S. Marines who were

providing security were withdrawing and arranging the demolition of the

DAO office, American equipment, files, and cash. Air America UH-1s also participated in the evacuation.

The original evacuation plans had not called for a large-scale helicopter operation at the United States Embassy, Saigon.

Helicopters and buses were to shuttle people from the embassy to the

DAO Compound. However, in the course of the evacuation it turned out

that a few thousand people were stranded at the embassy, including many

Vietnamese. Additional Vietnamese civilians gathered outside the embassy

and scaled the walls, hoping to claim refugee status. Thunderstorms

increased the difficulty of helicopter operations. Nevertheless, the

evacuation from the embassy continued more or less unbroken throughout

the evening and night.

At 03:45 on the morning of 30 April, Kissinger and Ford ordered

Martin to evacuate only Americans from that point forward. Reluctantly,

Martin announced that only Americans were to be flown out, due to

worries that the North Vietnamese would soon take the city and the Ford

administration's desire to announce the completion of the American

evacuation.

Ambassador Martin was ordered by President Ford to board the evacuation

helicopter. The call sign of that helicopter was "Lady Ace 09", and the

pilot carried direct orders from President Ford for Ambassador Martin

to be on board. The pilot, Gerry Berry, had the orders written in

grease-pencil on his kneepads. Ambassador Martin's wife, Dorothy, had

already been evacuated by previous flights, and left behind her suitcase

so a South Vietnamese woman might be able to squeeze on board with her.

"Lady Ace 09" from HMM-165

and piloted by Berry, took off at 04:58—had Martin refused to leave,

the Marines had a reserve order to arrest him and carry him away to

ensure his safety.

The embassy evacuation had flown out 978 Americans and about 1,100

Vietnamese. The Marines who had been securing the embassy followed at

dawn, with the last aircraft leaving at 07:53. 420 Vietnamese and South

Koreans were left behind in the embassy compound, with an additional

crowd gathered outside the walls.

The Americans and the refugees they flew out were generally

allowed to leave without intervention from either the North or South

Vietnamese. Pilots of helicopters heading to Tan Son Nhat were aware

that PAVN anti-aircraft guns were tracking them, but they refrained from

firing. The Hanoi leadership, reckoning that completion of the

evacuation would lessen the risk of American intervention, had

instructed Dũng not to target the airlift itself.

Meanwhile, members of the police in Saigon had been promised evacuation

in exchange for protecting the American evacuation buses and control of

the crowds in the city during the evacuation.

Although this was the end of the American military operation,

Vietnamese continued to leave the country by boat and, where possible,

by aircraft. RVNAF pilots who had access to helicopters flew them

offshore to the American fleet, where they were able to land. Many RVNAF

helicopters were dumped into the ocean to make room on the decks for

more aircraft. RVNAF fighters and other planes also sought refuge in Thailand while two O-1s landed on USS Midway.

Ambassador Martin was flown out to the USS Blue Ridge,

where he pleaded for helicopters to return to the embassy compound to

pick up the few hundred remaining hopefuls waiting to be evacuated. Although

his pleas were overruled by President Ford, Martin was able to convince

the Seventh Fleet to remain on station for several days so any locals

who could make their way to sea via boat or aircraft might be rescued by

the waiting Americans.

Many Vietnamese nationals who were evacuated were allowed to enter the United States under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act.

Decades later, when the U.S. government reestablished diplomatic

relations with Vietnam, the former embassy building was returned to the

United States. The historic staircase that led to the rooftop helicopter

pad in the nearby apartment building used by the CIA and other U.S.

government employees was salvaged and is on permanent display at the Gerald R. Ford Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

Final assault

In

the early hours of 30 April, Dũng received orders from the Politburo to

attack. He then ordered his field commanders to advance directly to key

facilities and strategic points in the city. The first PAVN unit to enter the city was the 324th Division. By now, the government had not made any sort of appeals to the people for donations of blood, food, etc.

On the morning of 30 April, PAVN sappers attempted to seize the Newport Bridge

but were repulsed by the ARVN Airborne. At 09:00 the PAVN tank column

approached the bridge and came under fire from ARVN tanks which

destroyed the lead T-54, killing the PAVN Battalion commander.

The ARVN 3rd Task Force, 81st Ranger Group

commanded by Major Pham Chau Tai defended Tan Son Nhut and they were

joined by the remnants of the Loi Ho unit. At 07:15 on 30 April, the

PAVN 24th Regiment approached the Bay Hien intersection (10.793°N 106.653°E) 1.5 km from the main gate of Tan Son Nhat Air Base. The lead T-54 was hit by M67 recoilless rifle and then the next T-54 was hit by a shell from an M48 tank.

The PAVN infantry moved forward and engaged the ARVN in house to house

fighting forcing them to withdraw to the base by 08:45. The PAVN then

sent three tanks and an infantry battalion to assault the main gate and

they were met by intensive anti-tank and machine gun fire knocking out

the three tanks and killing at least twenty PAVN soldiers. The PAVN

tried to bring forward an 85mm antiaircraft gun

but the ARVN knocked it out before it could start firing. The PAVN 10th

Division ordered eight more tanks and another infantry battalion to

join the attack, but as they approached the Bay Hien intersection they

were hit by an airstrike from RVNAF jets operating from Binh Thuy Air Base

which destroyed two T-54s. The six surviving tanks arrived at the main

gate at 10:00 and began their attack, with two being knocked out by

antitank fire in front of the gate and another destroyed as it attempted

a flanking manoeuvre.

At 10:24, Minh announced an unconditional surrender. He ordered

all ARVN troops "to cease hostilities in calm and to stay where they

are", while inviting the Provisional Revolutionary Government to engage

in "a ceremony of orderly transfer of power so as to avoid any

unnecessary bloodshed in the population."

At approximately 10:30 Major Pham at Tan Son Nhut Air Base heard

of the surrender broadcast of President Minh and went to the ARVN Joint

General Staff Compound to seek instructions. He called General Minh who

told him to prepare to surrender. Pham reportedly told Minh, "If Viet

Cong tanks are entering Independence Palace we will come down there to

rescue you, sir." Minh refused Pham's suggestion and Pham then told his

men to withdraw from the base gates. At 11:30 the PAVN entered the base.

At Newport Bridge the ARVN and PAVN continued to exchange tank

and artillery fire until the ARVN commander received President Minh's

capitulation order over the radio. While the bridge was rigged with

approximately 4000lbs of demolition charges, the ARVN stood down and at

10:30 the PAVN column crossed the bridge.

Capitulation and final surrender announcement

The photo of

Françoise Demulder

showed the two tanks at the gates while Tank 390 technically entered

first and Lieutenant Bui Quang Than was running with the VC flag in his

hand

PAVN 203rd Tank Brigade (from 2nd Corps of Major general Nguyễn Hữu An) under the command of Commander Nguyễn Tất Tài and Political Commissar Bùi Văn Tùng was the first unit to burst through the gates of the Independence Palace around noon. Tank 843 (a Soviet T-54

tank) was the first to directly hit and struck the side gate of the

Palace. This historic moment was recorded by the Australian cameraman

Neil Davis. Tank 390 (a Chinese T-59

tank) then crashed through the main gate in the middle to enter the

front yard. For many years, the official record of Vietnamese government

and international historical sources maintained that Tank 843 was the

first one to enter the Presidential Palace. However, in 1995, French war photographer Françoise Demulder

published her photo showed that Tank 360 entered the main gate while

Tank 843 was still behind the steel columns of the smaller gate on the

right hand side (view from inside) and Tank 843's commander Bui Quang

Than was running with the NLF flag on his hand. Both tanks were declared national treasures in 2012 and each was displayed in a different museum in Hanoi. Lieutenant Bui Quang Than pulled down the Republic of Vietnam's flag on top of the Palace and raised the Viet Cong flag at 11:30 AM on 30 April 1975.

The Tank Brigade 203 soldiers entered the Palace and found Minh

and all members of his cabinet sitting and waiting for them. The

political commissar Lieutenant colonel Bui Van Tung arrived at the

Palace 10 minutes after the first tanks.

Minh realised this was the highest ranking officer around then said:

"We are waiting to hand over the cabinet", Tung replied immediately:

"You have nothing to hand over but your unconditional surrender to us".

Tung then wrote a speech announcing the surrender and dissolution of

what remained of the South Vietnamese government. He then escorted Minh

to the Radio Saigon

to read it in order to avoid further needless bloodshed. The surrender

announcement was recorded by German journalist Börries Gallasch's tape

recorder.

Colonel Bùi Tín,

a military journalist was at the Palace around noon to witnessed the

events. In his memoir, he confirmed that Lt.-Col Bui Van Tung was the

one accepted the surrender and wrote the statement for Minh. However, in an interview with WGBH Educational Foundation in 1981, he falsely claimed that he was the first high officer met Minh and accepted the surrender (with Tung's words).

This claim was repeated after his defection from Vietnam and sometimes

cited mistakenly by foreign correspondents and historians.

At 2:30 Minh announced the formal surrender of South Vietnam:

I, General Duong Van Minh,

president of the Saigon administration, appeal to the armed forces of

the Republic of Vietnam to laydown their arms and surrender

unconditionally to the forces of the Liberation Army of South Vietnam.

Furthermore, I declare that the Saigon government is completely

dissolved at all levels. From the Central government to the local

governments must be handed over to the Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam.

— Duong Van Minh on the transcript written by Bui Van Tung

Lieutenant colonel Bui Van Tung then took the microphone and

announced, "We, the representatives for the forces of the Liberation

Army of South Vietnam, solemnly declare that the City of Saigon was

completely liberated. We accepted the unconditional surrender of General

Dương Văn Minh, the president of the Saigon administration". This announcement marked the end of the Vietnam War.

Aftermath

Turnover of Saigon

The communists renamed the city after Ho Chi Minh, former President of North Vietnam, although the name "Saigon" continued to be used by many residents and others.

Order was slowly restored, although the by-then-deserted U.S. Embassy

was looted, along with many other businesses. Communications between the

outside world and Saigon were cut. The Viet Cong machinery in South

Vietnam was weakened, owing in part to the Phoenix Program, so the PAVN was responsible for maintaining order and General Trần Văn Trà, Dũng's administrative deputy, was placed in charge of the city. The new authorities held a victory rally on 7 May.

One objective of the Communist Party of Vietnam

was to reduce the population of Saigon, which had become swollen with

an influx of people during the war and was now overcrowded with high

unemployment. "Re-education classes" for former soldiers in the ARVN

indicated that in order to regain full standing in society they would

need to move from the city and take up farming. Handouts of rice to the

poor, while forthcoming, were tied to pledges to leave Saigon for the

countryside. According to the Vietnamese government, within two years of

the capture of the city one million people had left Saigon, and the

state had a target of 500,000 further departures.

Following the end of the war, according to official and

non-official estimates, between 200,000 and 300,000 South Vietnamese

were sent to re-education camps, where many endured torture, starvation, and disease while they were being forced to do hard labor.

The evacuation

Whether

the evacuation had been successful or not has been questioned following

the end of the war. Operation Frequent Wind was generally assessed as

an impressive achievement—Văn Tiến Dũng stated this in his memoirs and The New York Times described it as being carried out with "efficiency and bravery".

On the other hand, the airlift was also criticized for being too slow

and hesitant, and it was inadequate in removing Vietnamese civilians and

soldiers who were connected with the American presence.

The U.S. State Department estimated that the Vietnamese employees

of the U.S. Embassy in South Vietnam, past and present, and their

families totaled 90,000 people. In his testimony to Congress, Ambassador

Martin asserted that 22,294 such people were evacuated by the end of

April. In 1977, National Review

alleged that some 30,000 South Vietnamese had been systematically

killed using a list of CIA informants left behind by the U.S. embassy.

An iconic photograph of evacuees entering a CIA Air America helicopter on the roof of the apartment building at 22 Gia Long Street is frequently mischaracterized as showing an evacuation from the "U.S. Embassy" via a "military" helicopter.

Commemoration

30 April is celebrated as a public holiday in Vietnam as Reunification Day (though the official reunification of the nation actually occurred on 2 July 1976) or Liberation Day (Ngày Giải Phóng). Along with International Workers' Day on 1 May, most people take the day off work and there are public celebrations.

Among overseas Vietnamese the week of 30 April is referred to as "Black April" and it is also commemorated as a time of lamentation for the fall of Saigon and the fall of South Vietnam as a whole.

In popular culture