From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scale_invariance

In physics, mathematics and statistics, scale invariance is a feature of objects or laws that do not change if scales of length, energy, or other variables, are multiplied by a common factor, and thus represent a universality.

The technical term for this transformation is a dilatation (also known as dilation). Dilatations can form part of a larger conformal symmetry.

- In mathematics, scale invariance usually refers to an invariance of individual functions or curves. A closely related concept is self-similarity, where a function or curve is invariant under a discrete subset of the dilations. It is also possible for the probability distributions of random processes to display this kind of scale invariance or self-similarity.

- In classical field theory, scale invariance most commonly applies to the invariance of a whole theory under dilatations. Such theories typically describe classical physical processes with no characteristic length scale.

- In quantum field theory, scale invariance has an interpretation in terms of particle physics. In a scale-invariant theory, the strength of particle interactions does not depend on the energy of the particles involved.

- In statistical mechanics, scale invariance is a feature of phase transitions. The key observation is that near a phase transition or critical point, fluctuations occur at all length scales, and thus one should look for an explicitly scale-invariant theory to describe the phenomena. Such theories are scale-invariant statistical field theories, and are formally very similar to scale-invariant quantum field theories.

- Universality is the observation that widely different microscopic systems can display the same behaviour at a phase transition. Thus phase transitions in many different systems may be described by the same underlying scale-invariant theory.

- In general, dimensionless quantities are scale invariant. The analogous concept in statistics are standardized moments, which are scale invariant statistics of a variable, while the unstandardized moments are not.

Scale-invariant curves and self-similarity

In mathematics, one can consider the scaling properties of a function or curve f (x) under rescalings of the variable x. That is, one is interested in the shape of f (λx) for some scale factor λ, which can be taken to be a length or size rescaling. The requirement for f (x) to be invariant under all rescalings is usually taken to be

for some choice of exponent Δ, and for all dilations λ. This is equivalent to f being a homogeneous function of degree Δ.

Examples of scale-invariant functions are the monomials , for which Δ = n, in that clearly

An example of a scale-invariant curve is the logarithmic spiral, a kind of curve that often appears in nature. In polar coordinates (r, θ), the spiral can be written as

Allowing for rotations of the curve, it is invariant under all rescalings λ; that is, θ(λr) is identical to a rotated version of θ(r).

Projective geometry

The idea of scale invariance of a monomial generalizes in higher dimensions to the idea of a homogeneous polynomial, and more generally to a homogeneous function. Homogeneous functions are the natural denizens of projective space, and homogeneous polynomials are studied as projective varieties in projective geometry. Projective geometry is a particularly rich field of mathematics; in its most abstract forms, the geometry of schemes, it has connections to various topics in string theory.

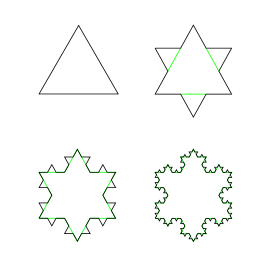

Fractals

It is sometimes said that fractals are scale-invariant, although more precisely, one should say that they are self-similar. A fractal is equal to itself typically for only a discrete set of values λ, and even then a translation and rotation may have to be applied to match the fractal up to itself.

Thus, for example, the Koch curve scales with ∆ = 1, but the scaling holds only for values of λ = 1/3n for integer n. In addition, the Koch curve scales not only at the origin, but, in a certain sense, "everywhere": miniature copies of itself can be found all along the curve.

Some fractals may have multiple scaling factors at play at once; such scaling is studied with multi-fractal analysis.

Periodic external and internal rays are invariant curves .

Scale invariance in stochastic processes

If P(f ) is the average, expected power at frequency f , then noise scales as

with Δ = 0 for white noise, Δ = −1 for pink noise, and Δ = −2 for Brownian noise (and more generally, Brownian motion).

More precisely, scaling in stochastic systems concerns itself with the likelihood of choosing a particular configuration out of the set of all possible random configurations. This likelihood is given by the probability distribution.

Examples of scale-invariant distributions are the Pareto distribution and the Zipfian distribution.

Scale invariant Tweedie distributions

Tweedie distributions are a special case of exponential dispersion models, a class of statistical models used to describe error distributions for the generalized linear model and characterized by closure under additive and reproductive convolution as well as under scale transformation. These include a number of common distributions: the normal distribution, Poisson distribution and gamma distribution, as well as more unusual distributions like the compound Poisson-gamma distribution, positive stable distributions, and extreme stable distributions. Consequent to their inherent scale invariance Tweedie random variables Y demonstrate a variance var(Y) to mean E(Y) power law:

- ,

where a and p are positive constants. This variance to mean power law is known in the physics literature as fluctuation scaling, and in the ecology literature as Taylor's law.

Random sequences, governed by the Tweedie distributions and evaluated by the method of expanding bins exhibit a biconditional relationship between the variance to mean power law and power law autocorrelations. The Wiener–Khinchin theorem further implies that for any sequence that exhibits a variance to mean power law under these conditions will also manifest 1/f noise.

The Tweedie convergence theorem provides a hypothetical explanation for the wide manifestation of fluctuation scaling and 1/f noise. It requires, in essence, that any exponential dispersion model that asymptotically manifests a variance to mean power law will be required express a variance function that comes within the domain of attraction of a Tweedie model. Almost all distribution functions with finite cumulant generating functions qualify as exponential dispersion models and most exponential dispersion models manifest variance functions of this form. Hence many probability distributions have variance functions that express this asymptotic behavior, and the Tweedie distributions become foci of convergence for a wide range of data types.

Much as the central limit theorem requires certain kinds of random variables to have as a focus of convergence the Gaussian distribution and express white noise, the Tweedie convergence theorem requires certain non-Gaussian random variables to express 1/f noise and fluctuation scaling.

Cosmology

In physical cosmology, the power spectrum of the spatial distribution of the cosmic microwave background is near to being a scale-invariant function. Although in mathematics this means that the spectrum is a power-law, in cosmology the term "scale-invariant" indicates that the amplitude, P(k), of primordial fluctuations as a function of wave number, k, is approximately constant, i.e. a flat spectrum. This pattern is consistent with the proposal of cosmic inflation.

Scale invariance in classical field theory

Classical field theory is generically described by a field, or set of fields, φ, that depend on coordinates, x. Valid field configurations are then determined by solving differential equations for φ, and these equations are known as field equations.

For a theory to be scale-invariant, its field equations should be invariant under a rescaling of the coordinates, combined with some specified rescaling of the fields,

The parameter Δ is known as the scaling dimension of the field, and its value depends on the theory under consideration. Scale invariance will typically hold provided that no fixed length scale appears in the theory. Conversely, the presence of a fixed length scale indicates that a theory is not scale-invariant.

A consequence of scale invariance is that given a solution of a scale-invariant field equation, we can automatically find other solutions by rescaling both the coordinates and the fields appropriately. In technical terms, given a solution, φ(x), one always has other solutions of the form

- .

Scale invariance of field configurations

For a particular field configuration, φ(x), to be scale-invariant, we require that

where Δ is, again, the scaling dimension of the field.

We note that this condition is rather restrictive. In general, solutions even of scale-invariant field equations will not be scale-invariant, and in such cases the symmetry is said to be spontaneously broken.

Classical electromagnetism

An example of a scale-invariant classical field theory is electromagnetism with no charges or currents. The fields are the electric and magnetic fields, E(x,t) and B(x,t), while their field equations are Maxwell's equations.

With no charges or currents, these field equations take the form of wave equations

where c is the speed of light.

These field equations are invariant under the transformation

Moreover, given solutions of Maxwell's equations, E(x, t) and B(x, t), it holds that E(λx, λt) and B(λx, λt) are also solutions.

Massless scalar field theory

Another example of a scale-invariant classical field theory is the massless scalar field (note that the name scalar is unrelated to scale invariance). The scalar field, φ(x, t) is a function of a set of spatial variables, x, and a time variable, t.

Consider first the linear theory. Like the electromagnetic field equations above, the equation of motion for this theory is also a wave equation,

and is invariant under the transformation

The name massless refers to the absence of a term in the field equation. Such a term is often referred to as a `mass' term, and would break the invariance under the above transformation. In relativistic field theories, a mass-scale, m is physically equivalent to a fixed length scale through

and so it should not be surprising that massive scalar field theory is not scale-invariant.

φ4 theory

The field equations in the examples above are all linear in the fields, which has meant that the scaling dimension, Δ, has not been so important. However, one usually requires that the scalar field action is dimensionless, and this fixes the scaling dimension of φ. In particular,

where D is the combined number of spatial and time dimensions.

Given this scaling dimension for φ, there are certain nonlinear modifications of massless scalar field theory which are also scale-invariant. One example is massless φ4 theory for D=4. The field equation is

(Note that the name φ4 derives from the form of the Lagrangian, which contains the fourth power of φ.)

When D=4 (e.g. three spatial dimensions and one time dimension), the scalar field scaling dimension is Δ=1. The field equation is then invariant under the transformation

The key point is that the parameter g must be dimensionless, otherwise one introduces a fixed length scale into the theory: For φ4 theory, this is only the case in D=4. Note that under these transformations the argument of the function φ is unchanged.

Scale invariance in quantum field theory

The scale-dependence of a quantum field theory (QFT) is characterised by the way its coupling parameters depend on the energy-scale of a given physical process. This energy dependence is described by the renormalization group, and is encoded in the beta-functions of the theory.

For a QFT to be scale-invariant, its coupling parameters must be independent of the energy-scale, and this is indicated by the vanishing of the beta-functions of the theory. Such theories are also known as fixed points of the corresponding renormalization group flow.

Quantum electrodynamics

A simple example of a scale-invariant QFT is the quantized electromagnetic field without charged particles. This theory actually has no coupling parameters (since photons are massless and non-interacting) and is therefore scale-invariant, much like the classical theory.

However, in nature the electromagnetic field is coupled to charged particles, such as electrons. The QFT describing the interactions of photons and charged particles is quantum electrodynamics (QED), and this theory is not scale-invariant. We can see this from the QED beta-function. This tells us that the electric charge (which is the coupling parameter in the theory) increases with increasing energy. Therefore, while the quantized electromagnetic field without charged particles is scale-invariant, QED is not scale-invariant.

Massless scalar field theory

Free, massless quantized scalar field theory has no coupling parameters. Therefore, like the classical version, it is scale-invariant. In the language of the renormalization group, this theory is known as the Gaussian fixed point.

However, even though the classical massless φ4 theory is scale-invariant in D=4, the quantized version is not scale-invariant. We can see this from the beta-function for the coupling parameter, g.

Even though the quantized massless φ4 is not scale-invariant, there do exist scale-invariant quantized scalar field theories other than the Gaussian fixed point. One example is the Wilson–Fisher fixed point, below.

Conformal field theory

Scale-invariant QFTs are almost always invariant under the full conformal symmetry, and the study of such QFTs is conformal field theory (CFT). Operators in a CFT have a well-defined scaling dimension, analogous to the scaling dimension, ∆, of a classical field discussed above. However, the scaling dimensions of operators in a CFT typically differ from those of the fields in the corresponding classical theory. The additional contributions appearing in the CFT are known as anomalous scaling dimensions.

Scale and conformal anomalies

The φ4 theory example above demonstrates that the coupling parameters of a quantum field theory can be scale-dependent even if the corresponding classical field theory is scale-invariant (or conformally invariant). If this is the case, the classical scale (or conformal) invariance is said to be anomalous. A classically scale invariant field theory, where scale invariance is broken by quantum effects, provides an explication of the nearly exponential expansion of the early universe called cosmic inflation, as long as the theory can be studied through perturbation theory.

Phase transitions

In statistical mechanics, as a system undergoes a phase transition, its fluctuations are described by a scale-invariant statistical field theory. For a system in equilibrium (i.e. time-independent) in D spatial dimensions, the corresponding statistical field theory is formally similar to a D-dimensional CFT. The scaling dimensions in such problems are usually referred to as critical exponents, and one can in principle compute these exponents in the appropriate CFT.

The Ising model

An example that links together many of the ideas in this article is the phase transition of the Ising model, a simple model of ferromagnetic substances. This is a statistical mechanics model, which also has a description in terms of conformal field theory. The system consists of an array of lattice sites, which form a D-dimensional periodic lattice. Associated with each lattice site is a magnetic moment, or spin, and this spin can take either the value +1 or −1. (These states are also called up and down, respectively.)

The key point is that the Ising model has a spin-spin interaction, making it energetically favourable for two adjacent spins to be aligned. On the other hand, thermal fluctuations typically introduce a randomness into the alignment of spins. At some critical temperature, Tc , spontaneous magnetization is said to occur. This means that below Tc the spin-spin interaction will begin to dominate, and there is some net alignment of spins in one of the two directions.

An example of the kind of physical quantities one would like to calculate at this critical temperature is the correlation between spins separated by a distance r. This has the generic behaviour:

for some particular value of , which is an example of a critical exponent.

CFT description

The fluctuations at temperature Tc are scale-invariant, and so the Ising model at this phase transition is expected to be described by a scale-invariant statistical field theory. In fact, this theory is the Wilson–Fisher fixed point, a particular scale-invariant scalar field theory.

In this context, G(r) is understood as a correlation function of scalar fields,

Now we can fit together a number of the ideas seen already.

From the above, one sees that the critical exponent, η, for this phase transition, is also an anomalous dimension. This is because the classical dimension of the scalar field,

is modified to become

where D is the number of dimensions of the Ising model lattice.

So this anomalous dimension in the conformal field theory is the same as a particular critical exponent of the Ising model phase transition.

Note that for dimension D ≡ 4−ε, η can be calculated approximately, using the epsilon expansion, and one finds that

- .

In the physically interesting case of three spatial dimensions, we have ε=1, and so this expansion is not strictly reliable. However, a semi-quantitative prediction is that η is numerically small in three dimensions.

On the other hand, in the two-dimensional case the Ising model is exactly soluble. In particular, it is equivalent to one of the minimal models, a family of well-understood CFTs, and it is possible to compute η (and the other critical exponents) exactly,

- .

Schramm–Loewner evolution

The anomalous dimensions in certain two-dimensional CFTs can be related to the typical fractal dimensions of random walks, where the random walks are defined via Schramm–Loewner evolution (SLE). As we have seen above, CFTs describe the physics of phase transitions, and so one can relate the critical exponents of certain phase transitions to these fractal dimensions. Examples include the 2d critical Ising model and the more general 2d critical Potts model. Relating other 2d CFTs to SLE is an active area of research.

Universality

A phenomenon known as universality is seen in a large variety of physical systems. It expresses the idea that different microscopic physics can give rise to the same scaling behaviour at a phase transition. A canonical example of universality involves the following two systems:

- The Ising model phase transition, described above.

- The liquid-vapour transition in classical fluids.

Even though the microscopic physics of these two systems is completely different, their critical exponents turn out to be the same. Moreover, one can calculate these exponents using the same statistical field theory. The key observation is that at a phase transition or critical point, fluctuations occur at all length scales, and thus one should look for a scale-invariant statistical field theory to describe the phenomena. In a sense, universality is the observation that there are relatively few such scale-invariant theories.

The set of different microscopic theories described by the same scale-invariant theory is known as a universality class. Other examples of systems which belong to a universality class are:

- Avalanches in piles of sand. The likelihood of an avalanche is in power-law proportion to the size of the avalanche, and avalanches are seen to occur at all size scales.

- The frequency of network outages on the Internet, as a function of size and duration.

- The frequency of citations of journal articles, considered in the network of all citations amongst all papers, as a function of the number of citations in a given paper.

- The formation and propagation of cracks and tears in materials ranging from steel to rock to paper. The variations of the direction of the tear, or the roughness of a fractured surface, are in power-law proportion to the size scale.

- The electrical breakdown of dielectrics, which resemble cracks and tears.

- The percolation of fluids through disordered media, such as petroleum through fractured rock beds, or water through filter paper, such as in chromatography. Power-law scaling connects the rate of flow to the distribution of fractures.

- The diffusion of molecules in solution, and the phenomenon of diffusion-limited aggregation.

- The distribution of rocks of different sizes in an aggregate mixture that is being shaken (with gravity acting on the rocks).

The key observation is that, for all of these different systems, the behaviour resembles a phase transition, and that the language of statistical mechanics and scale-invariant statistical field theory may be applied to describe them.

Other examples of scale invariance

Newtonian fluid mechanics with no applied forces

Under certain circumstances, fluid mechanics is a scale-invariant classical field theory. The fields are the velocity of the fluid flow, , the fluid density, , and the fluid pressure, . These fields must satisfy both the Navier–Stokes equation and the continuity equation. For a Newtonian fluid these take the respective forms

where is the dynamic viscosity.

In order to deduce the scale invariance of these equations we specify an equation of state, relating the fluid pressure to the fluid density. The equation of state depends on the type of fluid and the conditions to which it is subjected. For example, we consider the isothermal ideal gas, which satisfies

where is the speed of sound in the fluid. Given this equation of state, Navier–Stokes and the continuity equation are invariant under the transformations

Given the solutions and , we automatically have that and are also solutions.

Hidden scale invariance in liquids and solids

Certain models studied by Molecular Dynamics computer simulations, including the Lennard-Jones and Yukawa pair-potential models, have a potential-energy function that to a good approximation obeys the "hidden scale invariance" criterion

Here and are the full spatial coordinates of two same-density configuration and is a parameter that uniformly scales the configurations to a different density. Hidden scale invariance means that the ordering of configurations at one density according to their potential energy is maintained if these are scaled uniformly to a different density. This only applies rigorously for systems with an Euler-homogeneous potential-energy function, e.g., systems of particles interacting with inverse-power-law pair potentials. When hidden scale invariance implies for most configurations, this implies the existence of lines in the thermodynamic phase diagram, so-called "isomorphs", along which structure and dynamics in reduced units are invariant to a good approximation. It is believed that most metals and van der Waals bonded systems obey this approximate symmetry in the liquid and solid phases, whereas systems with strong directional bonds like covalently or hydrogen-bonded systems do not; ionic and dipolar systems constitute a class in-between. Most systems do not obey hidden scale invariance in the gas phase. Since an isomorph is line of constant excess entropy, the existence of isomorphs explains to a large extent the excess-entropy scaling discovered by Rosenfeld in 1977 and why this applies also to mixtures, confined systems, molecular systems, etc.

Computer vision

In computer vision and biological vision, scaling transformations arise because of the perspective image mapping and because of objects having different physical size in the world. In these areas, scale invariance refers to local image descriptors or visual representations of the image data that remain invariant when the local scale in the image domain is changed. Detecting local maxima over scales of normalized derivative responses provides a general framework for obtaining scale invariance from image data. Examples of applications include blob detection, corner detection, ridge detection, and object recognition via the scale-invariant feature transform.

![{\text{var}}\,(Y)=a[{\text{E}}\,(Y)]^{p}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4940e0d134bf31f4009cc68ea9e66a87bd0c16a7)