Though citizenship is often legally conflated with nationality in today's Anglo-Saxon world, international law does not usually use the term citizenship to refer to nationality, these two notions being conceptually different dimensions of collective membership.

Generally citizenships have no expiration and allow persons to work, reside and vote in the polity, as well as identify with the polity, possibly acquiring a passport. Though through discriminatory laws, like disfranchisement and outright apartheid citizens have been made second-class citizens. Historically, populations of states were mostly subjects, while citizenship was a particular status which originated in the rights of urban populations, like the rights of the male public of cities and republics, particularly ancient city-states, giving rise to a civitas and the social class of the burgher or bourgeoisie. Since then states have expanded the status of citizenship to most of their national people, while the extent of citizen rights remain contested.

Definition

Conceptually citizenship and nationality are different dimensions of state membership. Citizenship is focused on the internal political life of the state and nationality is the dimension of state membership in international law. Article 15 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that everyone has the right to nationality. As such nationality in international law can be called and understood as citizenship, or more generally as subject or belonging to a sovereign state, and not as ethnicity. This notwithstanding, around 10 million people are stateless.

In the contemporary era, the concept of full citizenship encompasses not only active political rights, but full civil rights and social rights.

Historically, the most significant difference between a national and a citizen is that the citizen has the right to vote for elected officials, and the right to be elected. This distinction between full citizenship and other, lesser relationships goes back to antiquity. Until the 19th and 20th centuries, it was typical for only a certain percentage of people who belonged to the state to be considered as full citizens. In the past, a number of people were excluded from citizenship on the basis of sex, socioeconomic class, ethnicity, religion, and other factors. However, they held a legal relationship with their government akin to the modern concept of nationality.Determining factors

A person can be recognized as a citizen on a number of bases.

- Nationality. Nationality and citizenship are generally indissociable, citizenship being in most cases a consequence of nationality.

- Place of residence. In some countries, foreign residents have citizenship rights and can vote.

- Citizenship by honorary conferment. This type of citizenship is conferred to an individual as a sign of honour.

- Excluded categories. In most countries, minors are not considered as full citizens. In the past, there have been exclusions on entitlement to citizenship on grounds such as skin color, ethnicity, sex, land ownership status, and free status (not being a slave). Most of these exclusions no longer apply in most places. Modern examples include some Gulf countries which rarely grant citizenship to non-Muslims, e.g. Qatar is known for granting citizenship to foreign athletes, but they all have to profess the Islamic faith in order to receive citizenship. The United States grants citizenship to those born as a result of reproductive technologies, and internationally adopted children born after February 27, 1983. Some exclusions still persist for internationally adopted children born before February 27, 1983, even though their parents meet citizenship criteria.

Responsibilities of a citizen

Every citizen has obligations that are required by law and some responsibilities that benefit the community. Obeying the laws of a country and paying taxes are some of the obligations required of citizens by law. Voting and community services form part of responsibilities of a citizen that benefits the community.

The Constitution of Ghana (1992), Article 41, obligates citizens to promote the prestige and good name of Ghana and respect the symbols of Ghana. Examples of national symbols includes the Ghanaian flag, coat of arms, money, and state sword. These national symbols must be treated with respect and high esteem by citizens since they best represent Ghanaians.

Apart from responsibilities, citizens also have rights. Some of the rights are the right to pursue life, liberty and happiness, the right to worship, right to run for elected office and right to express oneself.

Polis

Many thinkers such as Giorgio Agamben in his work extending the biopolitical framework of Foucault's History of Sexuality in the book, Homo Sacer, point to the concept of citizenship beginning in the early city-states of ancient Greece, although others see it as primarily a modern phenomenon dating back only a few hundred years and, for humanity, that the concept of citizenship arose with the first laws. Polis meant both the political assembly of the city-state as well as the entire society. Citizenship concept has generally been identified as a western phenomenon. There is a general view that citizenship in ancient times was a simpler relation than modern forms of citizenship, although this view has come under scrutiny. The relation of citizenship has not been a fixed or static relation but constantly changed within each society, and that according to one view, citizenship might "really have worked" only at select periods during certain times, such as when the Athenian politician Solon made reforms in the early Athenian state. Citizenship was also contingent on a variety of biopolitical assemblages, such as the bioethics of emerging Theo-Philosophical traditions. It was necessary to fit Aristotle's definition of the besouled (the animate) to obtain citizenship: neither the sacred olive tree nor spring would have any rights.

An essential part of the framework of Greco-Roman ethics is the figure of Homo Sacer or the bare life.

Historian Geoffrey Hosking in his 2005 Modern Scholar lecture course suggested that citizenship in ancient Greece arose from an appreciation for the importance of freedom. Hosking explained:

It can be argued that this growth of slavery was what made Greeks particularly conscious of the value of freedom. After all, any Greek farmer might fall into debt and therefore might become a slave, at almost any time ... When the Greeks fought together, they fought in order to avoid being enslaved by warfare, to avoid being defeated by those who might take them into slavery. And they also arranged their political institutions so as to remain free men.

— Geoffrey Hosking, 2005

Slavery permitted slave-owners to have substantial free time and enabled participation in public life.[20] Polis citizenship was marked by exclusivity. Inequality of status was widespread; citizens (πολίτης politēs < πόλις 'city') had a higher status than non-citizens, such as women, slaves, and resident foreigners (metics). The first form of citizenship was based on the way people lived in the ancient Greek times, in small-scale organic communities of the polis. The obligations of citizenship were deeply connected to one's everyday life in the polis. These small-scale organic communities were generally seen as a new development in world history, in contrast to the established ancient civilizations of Egypt or Persia, or the hunter-gatherer bands elsewhere. From the viewpoint of the ancient Greeks, a person's public life could not be separated from their private life, and Greeks did not distinguish between the two worlds according to the modern western conception. The obligations of citizenship were deeply connected with everyday life. To be truly human, one had to be an active citizen to the community, which Aristotle famously expressed: "To take no part in the running of the community's affairs is to be either a beast or a god!" This form of citizenship was based on the obligations of citizens towards the community, rather than rights given to the citizens of the community. This was not a problem because they all had a strong affinity with the polis; their own destiny and the destiny of the community were strongly linked. Also, citizens of the polis saw obligations to the community as an opportunity to be virtuous, it was a source of honor and respect. In Athens, citizens were both rulers and ruled, important political and judicial offices were rotated and all citizens had the right to speak and vote in the political assembly.

Roman ideas

In the Roman Empire, citizenship expanded from small-scale communities to the entirety of the empire. Romans realized that granting citizenship to people from all over the empire legitimized Roman rule over conquered areas. Roman citizenship was no longer a status of political agency, as it had been reduced to a judicial safeguard and the expression of rule and law. Rome carried forth Greek ideas of citizenship such as the principles of equality under the law, civic participation in government, and notions that "no one citizen should have too much power for too long", but Rome offered relatively generous terms to its captives, including chances for lesser forms of citizenship. If Greek citizenship was an "emancipation from the world of things", the Roman sense increasingly reflected the fact that citizens could act upon material things as well as other citizens, in the sense of buying or selling property, possessions, titles, goods. One historian explained:

The person was defined and represented through his actions upon things; in the course of time, the term property came to mean, first, the defining characteristic of a human or other being; second, the relation which a person had with a thing; and third, the thing defined as the possession of some person.

— J. G. A. Pocock, 1998

Roman citizenship reflected a struggle between the upper-class patrician interests against the lower-order working groups known as the plebeian class. A citizen came to be understood as a person "free to act by law, free to ask and expect the law's protection, a citizen of such and such a legal community, of such and such a legal standing in that community". Citizenship meant having rights to have possessions, immunities, expectations, which were "available in many kinds and degrees, available or unavailable to many kinds of person for many kinds of reason". The law itself was a kind of bond uniting people. Roman citizenship was more impersonal, universal, multiform, having different degrees and applications.

Middle Ages

During the European Middle Ages, citizenship was usually associated with cities and towns (see medieval commune), and applied mainly to middle-class folk. Titles such as burgher, grand burgher (German Großbürger) and the bourgeoisie denoted political affiliation and identity in relation to a particular locality, as well as membership in a mercantile or trading class; thus, individuals of respectable means and socioeconomic status were interchangeable with citizens.

During this era, members of the nobility had a range of privileges above commoners (see aristocracy), though political upheavals and reforms, beginning most prominently with the French Revolution, abolished privileges and created an egalitarian concept of citizenship.

Renaissance

During the Renaissance, people transitioned from being subjects of a king or queen to being citizens of a city and later to a nation. Each city had its own law, courts, and independent administration. And being a citizen often meant being subject to the city's law in addition to having power in some instances to help choose officials. City dwellers who had fought alongside nobles in battles to defend their cities were no longer content with having a subordinate social status but demanded a greater role in the form of citizenship. Membership in guilds was an indirect form of citizenship in that it helped their members succeed financially. The rise of citizenship was linked to the rise of republicanism, according to one account, since independent citizens meant that kings had less power. Citizenship became an idealized, almost abstract, concept, and did not signify a submissive relation with a lord or count, but rather indicated the bond between a person and the state in the rather abstract sense of having rights and duties.

Modern times

The modern idea of citizenship still respects the idea of political participation, but it is usually done through "elaborate systems of political representation at a distance" such as representative democracy. Modern citizenship is much more passive; action is delegated to others; citizenship is often a constraint on acting, not an impetus to act. Nevertheless, citizens are usually aware of their obligations to authorities and are aware that these bonds often limit what they can do.

United States

From 1790 until the mid-twentieth century, United States law used racial criteria to establish citizenship rights and regulate who was eligible to become a naturalized citizen. The Naturalization Act of 1790, the first law in U.S. history to establish rules for citizenship and naturalization, barred citizenship to all people who were not of European descent, stating that "any alien being a free white person, who shall have resided within the limits and under the jurisdiction of the United States for the term of two years, maybe admitted to becoming a citizen thereof."

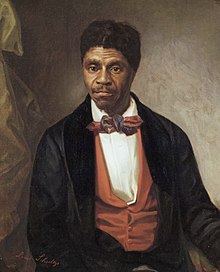

Under early U.S. laws, African Americans were not eligible for citizenship. In 1857, these laws were upheld in the US Supreme Court case Dred Scott v. Sandford, which ruled that "a free negro of the African race, whose ancestors were brought to this country and sold as slaves, is not a 'citizen' within the meaning of the Constitution of the United States," and that "the special rights and immunities guaranteed to citizens do not apply to them."

It was not until the abolition of slavery following the American Civil War that African Americans were granted citizenship rights. The 14th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, ratified on July 9, 1868, stated that "all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside." Two years later, the Naturalization Act of 1870 would extend the right to become a naturalized citizen to include "aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent".

Despite the gains made by African Americans after the Civil War, Native Americans, Asians, and others not considered "free white persons" were still denied the ability to become citizens. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act explicitly denied naturalization rights to all people of Chinese origin, while subsequent acts passed by the US Congress, such as laws in 1906, 1917, and 1924, would include clauses that denied immigration and naturalization rights to people based on broadly defined racial categories. Supreme Court cases such as Ozawa v. the United States (1922) and U.S. v. Bhagat Singh Thind (1923), would later clarify the meaning of the phrase "free white persons," ruling that ethnically Japanese, Indian, and other non-European people were not "white persons", and were therefore ineligible for naturalization under U.S. law.

Native Americans were not granted full US citizenship until the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act in 1924. However, even well into the 1960s, some state laws prevented Native Americans from exercising their full rights as citizens, such as the right to vote. In 1962, New Mexico became the last state to enfranchise Native Americans.

It was not until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 that the racial and gender restrictions for naturalization were explicitly abolished. However, the act still contained restrictions regarding who was eligible for US citizenship and retained a national quota system which limited the number of visas given to immigrants based on their national origin, to be fixed "at a rate of one-sixth of one percent of each nationality's population in the United States in 1920". It was not until the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that these immigration quota systems were drastically altered in favor of a less discriminatory system.

Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics

The 1918 constitution of revolutionary Russia granted citizenship to any foreigners who were living within the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, so long as they were "engaged in work and [belonged] to the working class." It recognized "the equal rights of all citizens, irrespective of their racial or national connections" and declared oppression of any minority group or race "to be contrary to the fundamental laws of the Republic." The 1918 constitution also established the right to vote and be elected to soviets for both men and women "irrespective of religion, nationality, domicile, etc. [...] who shall have completed their eighteenth year by the day of the election." The later constitutions of the USSR would grant universal Soviet citizenship to the citizens of all member republics in concord with the principles of non-discrimination laid out in the original 1918 constitution of Russia.

Nazi Germany

Nazism, the German variant of twentieth-century fascism, classified inhabitants of the country into three main hierarchical categories, each of which would have different rights in relation to the state: citizens, subjects, and aliens. The first category, citizens, were to possess full civic rights and responsibilities. Citizenship was conferred only on males of German (or so-called "Aryan") heritage who had completed military service, and could be revoked at any time by the state. The Reich Citizenship Law of 1935 established racial criteria for citizenship in the German Reich, and because of this law Jews and others who could not "prove German racial heritage" were stripped of their citizenship.

The second category, subjects, referred to all others who were born within the nation's boundaries who did not fit the racial criteria for citizenship. Subjects would have no voting rights, could not hold any position within the state, and possessed none of the other rights and civic responsibilities conferred on citizens. All women were to be conferred "subject" status upon birth, and could only obtain "citizen" status if they worked independently or if they married a German citizen (see women in Nazi Germany).

The final category, aliens, referred to those who were citizens of another state, who also had no rights.

In 2021, the German government passed Article 116 (2) of the Basic Law, which entitles the restoration of citizenship to individuals who had their German citizenship revoked "on political, racial, or religious grounds" between 30 January 1933 and 8 May 1945. This also entitles their descendants to German citizenship.

Israel

The primary principles of Israeli citizenship is jus sanguinis (citizenship by descent) for Jews and jus soli (citizenship by place of birth) for others.

Different senses

Many theorists suggest that there are two opposing conceptions of citizenship: an economic one, and a political one. For further information, see History of citizenship. Citizenship status, under social contract theory, carries with it both rights and duties. In this sense, citizenship was described as "a bundle of rights -- primarily, political participation in the life of the community, the right to vote, and the right to receive certain protection from the community, as well as obligations." Citizenship is seen by most scholars as culture-specific, in the sense that the meaning of the term varies considerably from culture to culture, and over time. In China, for example, there is a cultural politics of citizenship which could be called "peopleship", argued by an academic article.

How citizenship is understood depends on the person making the determination. The relation of citizenship has never been fixed or static, but constantly changes within each society. While citizenship has varied considerably throughout history, and within societies over time, there are some common elements but they vary considerably as well. As a bond, citizenship extends beyond basic kinship ties to unite people of different genetic backgrounds. It usually signifies membership in a political body. It is often based on or was a result of, some form of military service or expectation of future service. It usually involves some form of political participation, but this can vary from token acts to active service in government.

Citizenship is a status in society. It is an ideal state as well. It generally describes a person with legal rights within a given political order. It almost always has an element of exclusion, meaning that some people are not citizens and that this distinction can sometimes be very important, or not important, depending on a particular society. Citizenship as a concept is generally hard to isolate intellectually and compare with related political notions since it relates to many other aspects of society such as the family, military service, the individual, freedom, religion, ideas of right, and wrong, ethnicity, and patterns for how a person should behave in society. When there are many different groups within a nation, citizenship may be the only real bond that unites everybody as equals without discrimination—it is a "broad bond" linking "a person with the state" and gives people a universal identity as a legal member of a specific nation.

Modern citizenship has often been looked at as two competing underlying ideas:

- The liberal-individualist or sometimes liberal conception of citizenship suggests that citizens should have entitlements necessary for human dignity. It assumes people act for the purpose of enlightened self-interest. According to this viewpoint, citizens are sovereign, morally autonomous beings with duties to pay taxes, obey the law, engage in business transactions, and defend the nation if it comes under attack, but are essentially passive politically, and their primary focus is on economic betterment. This idea began to appear around the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries and became stronger over time, according to one view. According to this formulation, the state exists for the benefit of citizens and has an obligation to respect and protect the rights of citizens, including civil rights and political rights. It was later that so-called social rights became part of the obligation for the state.

- The civic-republican or sometimes classical or civic humanist conception of citizenship emphasizes man's political nature and sees citizenship as an active process, not a passive state or legal marker. It is relatively more concerned that government will interfere with popular places to practice citizenship in the public sphere. Citizenship means being active in government affairs. According to one view, most people today live as citizens according to the liberal-individualist conception but wished they lived more according to the civic-republican ideal. An ideal citizen is one who exhibits "good civic behavior". Free citizens and a republic government are "mutually interrelated." Citizenship suggested a commitment to "duty and civic virtue".

Responsibilities of citizens

Responsibility is an action that individuals of a state or country must take note of in the interest of a common good. These responsibilities can be categorised into personal and civic responsibilities.

Scholars suggest that the concept of citizenship contains many unresolved issues, sometimes called tensions, existing within the relation, that continue to reflect uncertainty about what citizenship is supposed to mean. Some unresolved issues regarding citizenship include questions about what is the proper balance between duties and rights. Another is a question about what is the proper balance between political citizenship versus social citizenship. Some thinkers see benefits with people being absent from public affairs, since too much participation such as revolution can be destructive, yet too little participation such as total apathy can be problematic as well. Citizenship can be seen as a special elite status, and it can also be seen as a democratizing force and something that everybody has; the concept can include both senses. According to sociologist Arthur Stinchcombe, citizenship is based on the extent that a person can control one's own destiny within the group in the sense of being able to influence the government of the group. One last distinction within citizenship is the so-called consent descent distinction, and this issue addresses whether citizenship is a fundamental matter determined by a person choosing to belong to a particular nation––by their consent––or is citizenship a matter of where a person was born––that is, by their descent.

International

Some intergovernmental organizations have extended the concept and terminology associated with citizenship to the international level, where it is applied to the totality of the citizens of their constituent countries combined. Citizenship at this level is a secondary concept, with rights deriving from national citizenship.

European Union

The Maastricht Treaty introduced the concept of citizenship of the European Union. Article 17 (1) of the Treaty on European Union stated that:

Citizenship of the Union is hereby established. Every person holding the nationality of a Member State shall be a citizen of the Union. Citizenship of the Union shall be additional to and not replace national citizenship.

An agreement is known as the amended EC Treaty established certain minimal rights for European Union citizens. Article 12 of the amended EC Treaty guaranteed a general right of non-discrimination within the scope of the Treaty. Article 18 provided a limited right to free movement and residence in the Member States other than that of which the European Union citizen is a national. Articles 18-21 and 225 provide certain political rights.

Union citizens have also extensive rights to move in order to exercise economic activity in any of the Member States which predate the introduction of Union citizenship.

Mercosur

Citizenship of the Mercosur is granted to eligible citizens of the Southern Common Market member states. It was approved in 2010 through the Citizenship Statute and should be fully implemented by the member countries in 2021 when the program will be transformed in an international treaty incorporated into the national legal system of the countries, under the concept of "Mercosur Citizen".

Commonwealth

The concept of "Commonwealth Citizenship" has been in place ever since the establishment of the Commonwealth of Nations. As with the EU, one holds Commonwealth citizenship only by being a citizen of a Commonwealth member state. This form of citizenship offers certain privileges within some Commonwealth countries:

- Some such countries do not require tourist visas of citizens of other Commonwealth countries or allow some Commonwealth citizens to stay in the country for tourism purposes without a visa for longer than citizens of other countries.

- In some Commonwealth countries, resident citizens of other Commonwealth countries are entitled to political rights, e.g., the right to vote in local and national elections and in some cases even the right to stand for election.

- In some instances the right to work in any position (including the civil service) is granted, except for certain specific positions, such as in the defense departments, Governor-General or President or Prime Minister.

- In the United Kingdom, all Commonwealth citizens legally residing in the country can vote and stand for office at all elections.

Although Ireland was excluded from the Commonwealth in 1949 because it declared itself a republic, Ireland is generally treated as if it were still a member. Legislation often specifically provides for equal treatment between Commonwealth countries and Ireland and refers to "Commonwealth countries and Ireland". Ireland's citizens are not classified as foreign nationals in the United Kingdom.

Canada departed from the principle of nationality being defined in terms of allegiance in 1921. In 1935 the Irish Free State was the first to introduce its own citizenship. However, Irish citizens were still treated as subjects of the Crown, and they are still not regarded as foreign, even though Ireland is not a member of the Commonwealth. The Canadian Citizenship Act of 1946 provided for a distinct Canadian Citizenship, automatically conferred upon most individuals born in Canada, with some exceptions, and defined the conditions under which one could become a naturalized citizen. The concept of Commonwealth citizenship was introduced in 1948 in the British Nationality Act 1948. Other dominions adopted this principle such as New Zealand, by way of the British Nationality and New Zealand Citizenship Act 1948.

Subnational

Citizenship most usually relates to membership of the nation-state, but the term can also apply at the subnational level. Subnational entities may impose requirements, of residency or otherwise, which permit citizens to participate in the political life of that entity or to enjoy benefits provided by the government of that entity. But in such cases, those eligible are also sometimes seen as "citizens" of the relevant state, province, or region. An example of this is how the fundamental basis of Swiss citizenship is a citizenship of an individual commune, from which follows citizenship of a canton and of the Confederation. Another example is Åland where the residents enjoy special provincial citizenship within Finland, hembygdsrätt.

The United States has a federal system in which a person is a citizen of their specific state of residence, such as New York or California, as well as a citizen of the United States. State constitutions may grant certain rights above and beyond what is granted under the United States Constitution and may impose their own obligations including the sovereign right of taxation and military service; each state maintains at least one military force subject to national militia transfer service, the state's national guard, and some states maintain a second military force not subject to nationalization.

Education

"Active citizenship" is the philosophy that citizens should work towards the betterment of their community through economic participation, public, volunteer work, and other such efforts to improve life for all citizens. In this vein, citizenship education is taught in schools, as an academic subject in some countries. By the time children reach secondary education there is an emphasis on such unconventional subjects to be included in an academic curriculum. While the diagram on citizenship to the right is rather facile and depthless, it is simplified to explain the general model of citizenship that is taught to many secondary school pupils. The idea behind this model within education is to instill in young pupils that their actions (i.e. their vote) affect collective citizenship and thus in turn them.

Republic of Ireland

It is taught in the Republic of Ireland as an exam subject for the Junior Certificate. It is known as Civic, Social and Political Education (CSPE). A new Leaving Certificate exam subject with the working title 'Politics & Society' is being developed by the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) and is expected to be introduced to the curriculum sometime after 2012.

United Kingdom

Citizenship is offered as a General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) course in many schools in the United Kingdom. As well as teaching knowledge about democracy, parliament, government, the justice system, human rights and the UK's relations with the wider world, students participate in active citizenship, often involving a social action or social enterprise in their local community.

- Citizenship is a compulsory subject of the National Curriculum in state schools in England for all pupils aged 11–16. Some schools offer a qualification in this subject at GCSE and A level. All state schools have a statutory requirement to teach the subject, assess pupil attainment and report student's progress in citizenship to parents.

- In Wales the model used is personal and social education.

- Citizenship is not taught as a discrete subject in Scottish schools, but is a cross-curricular strand of the Curriculum for Excellence. However they do teach a subject called "Modern Studies" which covers the social, political and economic study of local, national and international issues.

- Citizenship is taught as a standalone subject in all state schools in Northern Ireland and most other schools in some forms from year 8 to 10 prior to GCSEs. Components of Citizenship are then also incorporated into GCSE courses such as 'Learning for Life and Work'.