Modular self-reconfiguring robotic systems or self-reconfigurable modular robots are autonomous kinematic machines with variable morphology. Beyond conventional actuation, sensing and control typically found in fixed-morphology robots, self-reconfiguring robots are also able to deliberately change their own shape by rearranging the connectivity of their parts, in order to adapt to new circumstances, perform new tasks, or recover from damage.

For example, a robot made of such components could assume a worm-like shape to move through a narrow pipe, reassemble into something with spider-like legs to cross uneven terrain, then form a third arbitrary object (like a ball or wheel that can spin itself) to move quickly over a fairly flat terrain; it can also be used for making "fixed" objects, such as walls, shelters, or buildings.

In some cases this involves each module having 2 or more connectors for connecting several together. They can contain electronics, sensors, computer processors, memory and power supplies; they can also contain actuators that are used for manipulating their location in the environment and in relation with each other. A feature found in some cases is the ability of the modules to automatically connect and disconnect themselves to and from each other, and to form into many objects or perform many tasks moving or manipulating the environment.

By saying "self-reconfiguring" or "self-reconfigurable" it means that the mechanism or device is capable of utilizing its own system of control such as with actuators or stochastic means to change its overall structural shape. Having the quality of being "modular" in "self-reconfiguring modular robotics" is to say that the same module or set of modules can be added to or removed from the system, as opposed to being generically "modularized" in the broader sense. The underlying intent is to have an indefinite number of identical modules, or a finite and relatively small set of identical modules, in a mesh or matrix structure of self-reconfigurable modules.

Self-reconfiguration is different from the concept of self-replication, which is not a quality that a self-reconfigurable module or collection of modules needs to possess. A matrix of modules does not need to be able to increase the quantity of modules in its matrix to be considered self-reconfigurable. It is sufficient for self-reconfigurable modules to be produced at a conventional factory, where dedicated machines stamp or mold components that are then assembled into a module, and added to an existing matrix in order to supplement it to increase the quantity or to replace worn out modules.

A matrix made up of many modules can separate to form multiple matrices with fewer modules, or they can combine, or recombine, to form a larger matrix. Some advantages of separating into multiple matrices include the ability to tackle multiple and simpler tasks at locations that are remote from each other simultaneously, transferring through barriers with openings that are too small for a single larger matrix to fit through but not too small for smaller matrix fragments or individual modules, and energy saving purposes by only utilizing enough modules to accomplish a given task. Some advantages of combining multiple matrices into a single matrix is ability to form larger structures such as an elongated bridge, more complex structures such as a robot with many arms or an arm with more degrees of freedom, and increasing strength. Increasing strength, in this sense, can be in the form of increasing the rigidity of a fixed or static structure, increasing the net or collective amount of force for raising, lowering, pushing, or pulling another object, or another part of the matrix, or any combination of these features.

There are two basic methods of segment articulation that self-reconfigurable mechanisms can utilize to reshape their structures: chain reconfiguration and lattice reconfiguration.

Structure and control

Modular robots are usually composed of multiple building blocks of a relatively small repertoire, with uniform docking interfaces that allow transfer of mechanical forces and moments, electrical power and communication throughout the robot.

The modular building blocks usually consist of some primary structural actuated unit, and potentially additional specialized units such as grippers, feet, wheels, cameras, payload and energy storage and generation.

A taxonomy of architectures

Modular self-reconfiguring robotic systems can be generally classified into several architectural groups by the geometric arrangement of their unit (lattice vs. chain). Several systems exhibit hybrid properties, and modular robots have also been classified into the two categories of Mobile Configuration Change (MCC) and Whole Body Locomotion (WBL).

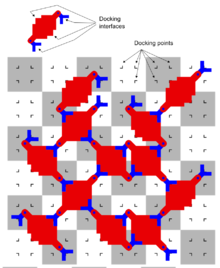

- Lattice architecture have their units connecting their docking interfaces at points into virtual cells of some regular grid. This network of docking points can be compared to atoms in a crystal and the grid to the lattice of that crystal. Therefore, the kinematical features of lattice robots can be characterized by their corresponding crystallographic displacement groups (chiral space groups). Usually few units are sufficient to accomplish a reconfiguration step. Lattice architectures allows a simpler mechanical design and a simpler computational representation and reconfiguration planning that can be more easily scaled to complex systems.

- Chain architecture do not use a virtual network of docking points for their units. The units are able to reach any point in the space and are therefore more versatile, but a chain of many units may be necessary to reach a point making it usually more difficult to accomplish a reconfiguration step. Such systems are also more computationally difficult to represent and analyze.

- Hybrid architecture takes advantages of both previous architectures. Control and mechanism are designed for lattice reconfiguration but also allow to reach any point in the space.

Modular robotic systems can also be classified according to the way by which units are reconfigured (moved) into place.

- Deterministic reconfiguration relies on units moving or being directly manipulated into their target location during reconfiguration. The exact location of each unit is known at all times. Reconfiguration times can be guaranteed, but sophisticated feedback control is necessary to assure precise manipulation. Macro-scale systems are usually deterministic.

- Stochastic reconfiguration relies on units moving around using statistical processes (like Brownian motion). The exact location of each unit only known when it is connected to the main structure, but it may take unknown paths to move between locations. Reconfiguration times can be guaranteed only statistically. Stochastic architectures are more favorable at micro scales.

Modular robotic systems are also generally classified depending on the design of the modules.

- Homogeneous modular robot systems have many modules of the same design forming a structure suitable to perform the required task. An advantage over other systems is that they are simple to scale in size (and possibly function), by adding more units. A commonly described disadvantage is limits to functionality - these systems often require more modules to achieve a given function, than heterogeneous systems.

- Heterogeneous modular robot systems have different modules,

each of which do specialized functions, forming a structure suitable to

perform a task. An advantage is compactness, and the versatility to

design and add units to perform any task. A commonly described

disadvantage is an increase in complexity of design, manufacturing, and

simulation methods.

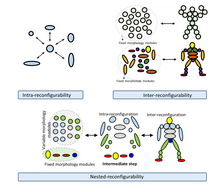

Conceptual representation for intra-, inter- and nested-reconfiguration under taxonomy of reconfigurable robots

Other modular robotic systems exist which are not self-reconfigurable, and thus do not formally belong to this family of robots though they may have similar appearance. For example, self-assembling systems may be composed of multiple modules but cannot dynamically control their target shape. Similarly, tensegrity robotics may be composed of multiple interchangeable modules but cannot self-reconfigure. Self-reconfigurable robotic systems feature reconfigurability compared to their fixed-morphology counterparts and it can be defined as the extent/degree to which a self-reconfigurable robot or robotic systems can transform and evolve to another meaningful configuration with a certain degree of autonomy or human intervention. The reconfigurable system can also be classified according to the mechanism reconfigurability.

- Intra-reconfigurability for robots is referred as a system that is a single entity while having ability to change morphology without the assembly/disassembly.

- Inter-reconfigurability is defined as to what extent a robotic system can change its morphology through assembling or disassembling its components or modules.

- Nested-reconfigurability for robotic system is a set of modular robots with individual reconfiguration characteristics (intra-reconfigurability) that combine with other homogeneous or heterogeneous robot modules (inter-reconfigurability).

Motivation and inspiration

There are two key motivations for designing modular self-reconfiguring robotic systems.

- Functional advantage: Self reconfiguring robotic systems are potentially more robust and more adaptive than conventional systems. The reconfiguration ability allows a robot or a group of robots to disassemble and reassemble machines to form new morphologies that are better suitable for new tasks, such as changing from a legged robot to a snake robot (snakebot) and then to a rolling robot. Since robot parts are interchangeable (within a robot and between different robots), machines can also replace faulty parts autonomously, leading to self-repair.

- Economic advantage: Self reconfiguring robotic systems can potentially lower overall robot cost by making a range of complex machines out of a single (or relatively few) types of mass-produced modules.

Both these advantages have not yet been fully realized. A modular robot is likely to be inferior in performance to any single custom robot tailored for a specific task. However, the advantage of modular robotics is only apparent when considering multiple tasks that would normally require a set of different robots.

The added degrees of freedom make modular robots more versatile in their potential capabilities, but also incur a performance tradeoff and increased mechanical and computational complexities.

The quest for self-reconfiguring robotic structures is to some extent inspired by envisioned applications such as long-term space missions, that require long-term self-sustaining robotic ecology that can handle unforeseen situations and may require self repair. A second source of inspiration are biological systems that are self-constructed out of a relatively small repertoire of lower-level building blocks (cells or amino acids, depending on scale of interest). This architecture underlies biological systems' ability to physically adapt, grow, heal, and even self replicate – capabilities that would be desirable in many engineered systems.

Application areas

Given these advantages, where would a modular self-reconfigurable system be used? While the system has the promise of being capable of doing a wide variety of things, finding the "killer application" has been somewhat elusive. Here are several examples:

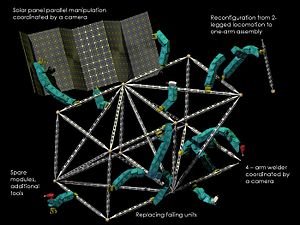

Space exploration

One application that highlights the advantages of self-reconfigurable systems is long-term space missions. These require long-term self-sustaining robotic ecology that can handle unforeseen situations and may require self repair. Self-reconfigurable systems have the ability to handle tasks that are not known a priori, especially compared to fixed configuration systems. In addition, space missions are highly volume- and mass-constrained. Sending a robot system that can reconfigure to achieve many tasks may be more effective than sending many robots that each can do one task.

Telepario

Another example of an application has been coined "telepario" by CMU professors Todd Mowry and Seth Goldstein. What the researchers propose to make are moving, physical, three-dimensional replicas of people or objects, so lifelike that human senses would accept them as real. This would eliminate the need for cumbersome virtual reality gear and overcome the viewing angle limitations of modern 3D approaches. The replicas would mimic the shape and appearance of a person or object being imaged in real time, and as the originals moved, so would their replicas. One aspect of this application is that the main development thrust is geometric representation rather than applying forces to the environment as in a typical robotic manipulation task. This project is widely known as claytronics or Programmable matter (noting that programmable matter is a much more general term, encompassing functional programmable materials, as well).

Bucket of stuff

A third long-term vision for these systems has been called "bucket of stuff", which would be a container filled with modular robots that can accept user commands and adopt an appropriate form in order to complete household chores.

History and state of the art

The roots of the concept of modular self-reconfigurable robots can be traced back to the "quick change" end effector and automatic tool changers in computer numerical controlled machining centers in the 1970s. Here, special modules each with a common connection mechanism could be automatically swapped out on the end of a robotic arm. However, taking the basic concept of the common connection mechanism and applying it to the whole robot was introduced by Toshio Fukuda with the CEBOT (short for cellular robot) in the late 1980s.

The early 1990s saw further development from Gregory S. Chirikjian, Mark Yim, Joseph Michael, and Satoshi Murata. Chirikjian, Michael, and Murata developed lattice reconfiguration systems and Yim developed a chain based system. While these researchers started with a mechanical engineering emphasis, designing and building modules then developing code to program them, the work of Daniela Rus and Wei-min Shen developed hardware but had a greater impact on the programming aspects. They started a trend towards provable or verifiable distributed algorithms for the control of large numbers of modules.

One of the more interesting hardware platforms recently has been the MTRAN II and III systems developed by Satoshi Murata et al. This system is a hybrid chain and lattice system. It has the advantage of being able to achieve tasks more easily like chain systems, yet reconfigure like a lattice system.

More recently new efforts in stochastic self-assembly have been pursued by Hod Lipson and Eric Klavins. A large effort at Carnegie Mellon University headed by Seth Goldstein and Todd Mowry has started looking at issues in developing millions of modules.

Many tasks have been shown to be achievable, especially with chain reconfiguration modules. This demonstrates the versatility of these systems however, the other two advantages, robustness and low cost have not been demonstrated. In general the prototype systems developed in the labs have been fragile and expensive as would be expected during any initial development.

There is a growing number of research groups actively involved in modular robotics research. To date, about 30 systems have been designed and constructed, some of which are shown below.

| System | Class, DOF | Author | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| CEBOT | Mobile | Fukuda et al. (Tsukuba) | 1988 |

| Polypod | Chain, 2, 3D | Yim (Stanford) | 1993 |

| Metamorphic | Lattice, 6, 2D | Chirikjian (Caltech) | 1993 |

| Fracta | Lattice, 3 2D | Murata (MEL) | 1994 |

| Fractal Robots | Lattice, 3D | Michael (UK) | 1994 |

| Tetrobot | Chain, 1 3D | Hamline et al. (RPI) | 1996 |

| 3D Fracta | Lattice, 6 3D | Murata et al. (MEL) | 1998 |

| Molecule | Lattice, 4 3D | Kotay & Rus (Dartmouth) | 1998 |

| CONRO | Chain, 2 3D | Will & Shen (USC/ISI) | 1998 |

| PolyBot | Chain, 1 3D | Yim et al. (PARC) | 1998 |

| TeleCube | Lattice, 6 3D | Suh et al., (PARC) | 1998 |

| Vertical | Lattice, 2D | Hosakawa et al., (Riken) | 1998 |

| Crystalline | Lattice, 4 2D | Vona & Rus, (Dartmouth) | 1999 |

| I-Cube | Lattice, 3D | Unsal, (CMU) | 1999 |

| Micro Unit | Lattice, 2 2D | Murata et al.(AIST) | 1999 |

| M-TRAN I | Hybrid, 2 3D | Murata et al.(AIST) | 1999 |

| Pneumatic | Lattice, 2D | Inou et al., (TiTech) | 2002 |

| Uni Rover | Mobile, 2 2D | Hirose et al., (TiTech) | 2002 |

| M-TRAN II | Hybrid, 2 3D | Murata et al., (AIST) | 2002 |

| Atron | Lattice, 1 3D | Stoy et al., (U.S Denmark) | 2003 |

| S-bot | Mobile, 3 2D | Mondada et al., (EPFL) | 2003 |

| Stochastic | Lattice, 0 3D | White, Kopanski, Lipson (Cornell) | 2004 |

| Superbot | Hybrid, 3 3D | Shen et al., (USC/ISI) | 2004 |

| Y1 Modules | Chain, 1 3D | Gonzalez-Gomez et al., (UAM) | 2004 |

| M-TRAN III | Hybrid, 2 3D | Kurokawa et al., (AIST) | 2005 |

| AMOEBA-I | Mobile, 7 3D | Liu JG et al., (SIA) | 2005 |

| Catom | Lattice, 0 2D | Goldstein et al., (CMU) | 2005 |

| Stochastic-3D | Lattice, 0 3D | White, Zykov, Lipson (Cornell) | 2005 |

| Molecubes | Hybrid, 1 3D | Zykov, Mytilinaios, Lipson (Cornell) | 2005 |

| Prog. parts | Lattice, 0 2D | Klavins, (U. Washington) | 2005 |

| Microtub | Chain, 2 2D | Brunete, Hernando, Gambao (UPM) | 2005 |

| Miche | Lattice, 0 3D | Rus et al., (MIT) | 2006 |

| GZ-I Modules | Chain, 1 3D | Zhang & Gonzalez-Gomez (U. Hamburg, UAM) | 2006 |

| The Distributed Flight Array | Lattice, 6 3D | Oung & D'Andrea (ETH Zurich) | 2008 |

| Evolve | Chain, 2 3D | Chang Fanxi, Francis (NUS) | 2008 |

| EM-Cube | Lattice, 2 2D | An, (Dran Computer Science Lab) | 2008 |

| Roombots | Hybrid, 3 3D | Sproewitz, Moeckel, Ijspeert, Biorobotics Laboratory, (EPFL) | 2009 |

| Programmable Matter by Folding | Sheet, 3D | Wood, Rus, Demaine et al., (Harvard & MIT) | 2010 |

| Sambot | Hybrid, 3D | HaiYuan Li, HongXing Wei, TianMiao Wang et al., (Beihang University) | 2010 |

| Moteins | Hybrid, 1 3D | Center for Bits and Atoms, (MIT) | 2011 |

| ModRED | Chain, 4 3D | C-MANTIC Lab, (UNO/UNL) | 2011 |

| Programmable Smart Sheet | Sheet, 3D | An & Rus, (MIT) | 2011 |

| SMORES | Hybrid, 4, 3D | Davey, Kwok, Yim (UNSW, UPenn) | 2012 |

| Symbrion | Hybrid, 3D | EU Projects Symbrion and Replicator | 2013 |

| ReBiS - Re-configurable Bipedal Snake[12] | Chain, 1, 3D | Rohan, Ajinkya, Sachin, S. Chiddarwar, K. Bhurchandi (VNIT, Nagpur) | 2014 |

| Soft Mod. Rob. Cubes | Lattice, 3D | Vergara, Sheng, Mendoza-Garcia, Zagal (UChile) | 2017 |

| Space Engine | Hybrid, 3D | Ruke Keragala (3rdVector, New York) | 2018 |

| Omni-Pi-tent | Hybrid, 3D | Peck, Timmis, Tyrrell (University of York) | 2019 |

| Panthera | Mobile, 1D | Elara, Prathap, Hayat, Parween (SUTD, Singapore) | 2019 |

| AuxBots | Chain, 3D | Chin, Burns, Xie, Rus (MIT, USA) | 2023 |

Some current systems

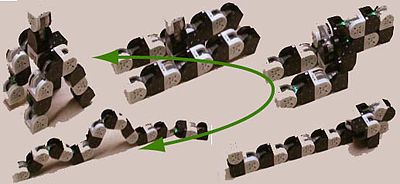

- PolyBot G3 (2002)

A chain self-reconfiguration system. Each module is about 50 mm on a side, and has 1 rotational DOF. It is part of the PolyBot modular robot family that has demonstrated many modes of locomotion including walking: biped, 14 legged, slinky-like, snake-like: concertina in a gopher hole, inchworm gaits, rectilinear undulation and sidewinding gaits, rolling like a tread at up to 1.4 m/s, riding a tricycle, climbing: stairs, poles pipes, ramps etc. More information can be found at the polybot webpage at PARC.

- M-TRAN III (2005)

A hybrid type self-reconfigurable system. Each module is two cube size (65 mm side), and has 2 rotational DOF and 6 flat surfaces for connection. It is the 3rd M-TRAN prototypes. Compared with the former (M-TRAN II), speed and reliability of connection is largely improved. As a chain type system, locomotion by CPG (Central Pattern Generator) controller in various shapes has been demonstrated by M-TRAN II. As a lattice type system, it can change its configuration, e.g., between a 4 legged walker to a caterpillar like robot. See the M-TRAN webpage at AIST.

- AMOEBA-I (2005)

AMOEBA-I, a three-module reconfigurable mobile robot was developed in Shenyang Institute of Automation (SIA), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) by Liu J G et al. AMOEBA-I has nine kinds of non-isomorphic configurations and high mobility under unstructured environments. Four generations of its platform have been developed and a series of researches have been carried out on their reconfiguration mechanism, non-isomorphic configurations, tipover stability, and reconfiguration planning. Experiments have demonstrated that such kind structure permits good mobility and high flexibility to uneven terrain. Being hyper-redundant, modularized and reconfigurable, AMOEBA-I has many possible applications such as Urban Search and Rescue (USAR) and space exploration.

Stochastic-3D (2005)

High spatial resolution for arbitrary three-dimensional shape formation with modular robots can be accomplished using lattice system with large quantities of very small, prospectively microscopic modules. At small scales, and with large quantities of modules, deterministic control over reconfiguration of individual modules will become unfeasible, while stochastic mechanisms will naturally prevail. Microscopic size of modules will make the use of electromagnetic actuation and interconnection prohibitive, as well, as the use of on-board power storage.

Three large scale prototypes were built in attempt to demonstrate dynamically programmable three-dimensional stochastic reconfiguration in a neutral-buoyancy environment. The first prototype used electromagnets for module reconfiguration and interconnection. The modules were 100 mm cubes and weighed 0.81 kg. The second prototype used stochastic fluidic reconfiguration and interconnection mechanism. Its 130 mm cubic modules weighed 1.78 kg each and made reconfiguration experiments excessively slow. The current third implementation inherits the fluidic reconfiguration principle. The lattice grid size is 80 mm, and the reconfiguration experiments are under way.

Molecubes (2005)

This hybrid self-reconfiguring system was built by the Cornell Computational Synthesis Lab to physically demonstrate artificial kinematic self-reproduction. Each module is a 0.65 kg cube with 100 mm long edges and one rotational degree of freedom. The axis of rotation is aligned with the cube's longest diagonal. Physical self-reproduction of both a three- and a four-module robot was demonstrated. It was also shown that, disregarding the gravity constraints, an infinite number of self-reproducing chain meta-structures can be built from Molecubes. More information can be found at the Creative Machines Lab self-replication page.

The Programmable Parts (2005)

The programmable parts are stirred randomly on an air-hockey table by randomly actuated air jets. When they collide and stick, they can communicate and decide whether to stay stuck, or if and when to detach. Local interaction rules can be devised and optimized to guide the robots to make any desired global shape. More information can be found at the programmable parts web page.

SuperBot (2006)

The SuperBot modules fall into the hybrid architecture. The modules have three degrees of freedom each. The design is based on two previous systems: Conro (by the same research group) and MTRAN (by Murata et al.). Each module can connect to another module through one of its six dock connectors. They can communicate and share power through their dock connectors. Several locomotion gaits have been developed for different arrangements of modules. For high-level communication the modules use hormone-based control, a distributed, scalable protocol that does not require the modules to have unique ID's.

Miche (2006)

The Miche system is a modular lattice system capable of arbitrary shape formation. Each module is an autonomous robot module capable of connecting to and communicating with its immediate neighbors. When assembled into a structure, the modules form a system that can be virtually sculpted using a computer interface and a distributed process. The group of modules collectively decide who is on the final shape and who is not using algorithms that minimize the information transmission and storage. Finally, the modules not in the structure let go and fall off under the control of an external force, in this case gravity. More details at Miche (Rus et al.).

The Distributed Flight Array (2009)

The Distributed Flight Array is a modular robot consisting of hexagonal-shaped single-rotor units that can take on just about any shape or form. Although each unit is capable of generating enough thrust to lift itself off the ground, on its own it is incapable of flight much like a helicopter cannot fly without its tail rotor. However, when joined, these units evolve into a sophisticated multi-rotor system capable of coordinated flight and much more. More information can be found at DFA.

Roombots (2009)

Roombots have a hybrid architecture. Each module has three degrees of freedom, two of them using the diametrical axis within a regular cube, and a third (center) axis of rotation connecting the two spherical parts. All three axes are continuously rotatory. The outer Roombots DOF is using the same axis-orientation as Molecubes, the third, central Roombots axis enables the module to rotate its two outer DOF against each other. This novel feature enables a single Roombots module to locomote on flat terrain, but also to climb a wall, or to cross a concave, perpendicular edge. Convex edges require the assembly of at least two modules into a Roombots "Metamodule". Each module has ten available connector slots, currently two of them are equipped with an active connection mechanism based on mechanical latches. Roombots are designed for two tasks: to eventually shape objects of daily life, e.g. furniture, and to locomote, e.g. as a quadruped or a tripod robot made from multiple modules. More information can be found at Roombots webpage.

Sambot (2010)

Being inspired from social insects, multicellular organism and morphogenetic robots, the aim of the Sambot is to develop swarm robotics and conduct research on the swarm intelligence, self-assembly and co-evolution of the body and brain for autonomous morphogeneous. Differing from swarm robot, self-reconfigurable robot and morphogenetic robot, the research focuses on self-assembly swarm modular robots that interact and dock as an autonomous mobile module with others to achieve swarm intelligence and furtherly discuss the autonomous construction in space station and exploratory tools and artificial complex structures. Each Sambot robot can run as an autonomous individual in wheel and besides, using combination of the sensors and docking mechanism, the robot can interact and dock with the environments and other robots. By the advantage of motion and connection, Sambot swarms can aggregate into a symbiotic or whole organism and generate locomotion as the bionic articular robots. In this case, some self-assembling, self-organizing, self-reconfiguring, and self-repairing function and research are available in design and application view. Inside the modular robot whose size is 80(W)X80(L)X102(H) mm, MCU (ARM and AVR), communication (Zigbee), sensors, power, IMU, positioning modules are embedded. More information can be found at "Self-assembly Swarm Modular Robots".

- Moteins (2011)

It is mathematically proven that physical strings or chains of simple shapes can be folded into any continuous area or volumetric shape. Moteins employ such shape-universal folding strategies, with as few as one (for 2D shapes) or two (for 3D shapes) degrees of freedom and simple actuators with as few as two (for 2D shapes) or three (for 3D shapes) states per unit.

- Symbrion (2013)

Symbrion (Symbiotic Evolutionary Robot Organisms) was a project funded by the European Commission between 2008 and 2013 to develop a framework in which a homogeneous swarm of miniature interdependent robots can co-assemble into a larger robotic organism to gain problem-solving momentum. One of the key aspects of Symbrion is inspired by the biological world: an artificial genome that allows storing and evolution of suboptimal configurations in order to increase the speed of adaptation. A large part of the developments within Symbrion is open-source and open-hardware.

- Space Engine (2018)

Space Engine is an autonomous kinematic platform with variable morphology, capable of creating or manipulating the physical space (living space, work space, recreation space). Generating its own multi-directional kinetic force to manipulate objects and perform tasks.

At least 3 or more locks for each module, able the automatically attach or detach to its immediate modules to form rigid structures. Modules propel in a linear motion forward or backward alone X, Y or Z spacial planes, while creates their own momentum forces, able to propel itself by the controlled pressure variation created between one or more of its immediate modules.

Using Magnetic pressures to attract and/or repel with its immediate modules. While the propelling module use its electromagnets to pull or push forward along the roadway created by The statistic modules, the statistic modules pull or push the propelling modules forward. Increasing the number of modular for displacement also increases the total momentum or push/pull forces. The number of Electromagnets on each module can change according to requirements of the design.

The modules on the exterior of the matrices can't displace independently on their own, due to lack of one or more reaction face from immediate modules. They are moved by attaching to modules in the interior of the matrices, that can form complete roadway for displacement.

- Space Engine Displacement

-

Space Engine Displacement

-

Space Engine Zero-gravity cell design

-

Space Engine gravity cell design

Quantitative accomplishment

- The robot with most active modules has 56 units <polybot centipede, PARC>

- The smallest actuated modular unit has a size of 12 mm

- The largest actuated modular unit (by volume) has the size of 8 m^3 <(GHFC)giant helium filled catoms, CMU>

- The strongest actuation modules are able to lift 5 identical horizontally cantilevered units.<PolyBot g1v5, PARC>

- The fastest modular robot can move at 23 unit-sizes/second.<CKbot, dynamic rolling, ISER'06>

- The largest simulated system contained many hundreds of thousands of units.

Challenges, solutions, and opportunities

Since the early demonstrations of early modular self-reconfiguring systems, the size, robustness and performance has been continuously improving. In parallel, planning and control algorithms have been progressing to handle thousands of units. There are, however, several key steps that are necessary for these systems to realize their promise of adaptability, robustness and low cost. These steps can be broken down into challenges in the hardware design, in planning and control algorithms and in application. These challenges are often intertwined.

Hardware design challenges

The extent to which the promise of self-reconfiguring robotic systems can be realized depends critically on the numbers of modules in the system. To date, only systems with up to about 50 units have been demonstrated, with this number stagnating over almost a decade. There are a number of fundamental limiting factors that govern this number:

- Limits on strength, precision, and field robustness (both mechanical and electrical) of bonding/docking interfaces between modules

- Limits on motor power, motion precision and energetic efficiency of units, (i.e. specific power, specific torque)

- Hardware/software design. Hardware that is designed to make the software problem easier. Self-reconfiguring systems have more tightly coupled hardware and software than any other existing system.

Planning and control challenges

Though algorithms have been developed for handling thousands of units in ideal conditions, challenges to scalability remain both in low-level control and high-level planning to overcome realistic constraints:

- Algorithms for parallel-motion for large scale manipulation and locomotion

- Algorithms for robustly handling a variety of failure modes, from misalignments, dead-units (not responding, not releasing) to units that behave erratically.

- Algorithms that determine the optimal configuration for a given task

- Algorithms for optimal (time, energy) reconfiguration plan

- Efficient and scalable (asynchronous) communication among multiple units

Application challenges

Though the advantages of Modular self-reconfiguring robotic systems is largely recognized, it has been difficult to identify specific application domains where benefits can be demonstrated in the short term. Some suggested applications are

- Space exploration and Space colonization applications, e.g. Lunar colonization

- Construction of large architectural systems

- Deep sea exploration/mining

- Search and rescue in unstructured environments

- Rapid construction of arbitrary tools under space/weight constraints

- Disaster relief shelters for displaced peoples

- Shelters for impoverished areas which require little on-the-ground expertise to assemble

Grand Challenges

Several robotic fields have identified Grand Challenges that act as a catalyst for development and serve as a short-term goal in absence of immediate killer apps. The Grand Challenge is not in itself a research agenda or milestone, but a means to stimulate and evaluate coordinated progress across multiple technical frontiers. Several Grand Challenges have been proposed for the modular self-reconfiguring robotics field:

- Demonstration of a system with >1000 units. Physical demonstration of such a system will inevitably require rethinking key hardware and algorithmic issues, as well as handling noise and error.

- Robosphere. A self-sustaining robotic ecology, isolated for a long period of time (1 year) that needs to sustain operation and accomplish unforeseen tasks without any human presence.

- Self replication A system with many units capable of self replication by collecting scattered building blocks will require solving many of the hardware and algorithmic challenges.

- Ultimate Construction A system capable of making objects out of the components of, say, a wall.

- Biofilter analogy If the system is ever made small enough to

be injected into a mammal, one task may be to monitor molecules in the

blood stream and allow some to pass and others not to, somewhat like the

blood–brain barrier. As a challenge, an analogy may be made where system must be able to:

- be inserted into a hole one module's diameter.

- travel some specified distance in a channel that is say roughly 40 x 40 module diameters in area.

- form a barrier fully conforming to the channel (whose shape is non-regular, and unknown beforehand).

- allow some objects to pass and others not to (not based on size).

- Since sensing is not the emphasis of this work, the actual detection of the passable objects should be made trivial.

Inductive transducers

A unique potential solution that can be exploited is the use of inductors as transducers. This could be useful for dealing with docking and bonding problems. At the same time it could also be beneficial for its capabilities of docking detection (alignment and finding distance), power transmission, and (data signal) communication. A proof-of-concept video can be seen here. The rather limited exploration down this avenue is probably a consequence of the historical lack of need in any applications for such an approach.

Google Groups

Self-Reconfiguring and Modular Technology is a group for discussion of the perception and understanding of the developing field.robotics.

Modular Robotics Google Group is an open public forum dedicated to announcements of events in the field of Modular Robotics. This medium is used to disseminate calls to workshops, special issues and other academic activities of interest to modular robotics researchers. The founders of this Google group intend it to facilitate the exchange of information and ideas within the community of modular robotics researchers around the world and thus promote acceleration of advancements in modular robotics. Anybody who is interested in objectives and progress of Modular Robotics can join this Google group and learn about the new developments in this field.