From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minkowski%27s_theorem

In mathematics, Minkowski's theorem is the statement that every convex set in which is symmetric with respect to the origin and which has volume greater than contains a non-zero integer point (meaning a point in that is not the origin). The theorem was proved by Hermann Minkowski in 1889 and became the foundation of the branch of number theory called the geometry of numbers. It can be extended from the integers to any lattice and to any symmetric convex set with volume greater than , where denotes the covolume of the lattice (the absolute value of the determinant of any of its bases).

Formulation

Suppose that L is a lattice of determinant d(L) in the n-dimensional real vector space and S is a convex subset of that is symmetric with respect to the origin, meaning that if x is in S then −x is also in S. Minkowski's theorem states that if the volume of S is strictly greater than 2n d(L), then S must contain at least one lattice point other than the origin. (Since the set S is symmetric, it would then contain at least three lattice points: the origin 0 and a pair of points ± x, where x ∈ L \ 0.)

Example

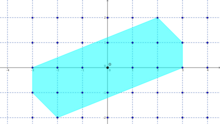

The simplest example of a lattice is the integer lattice of all points with integer coefficients; its determinant is 1. For n = 2, the theorem claims that a convex figure in the Euclidean plane symmetric about the origin and with area greater than 4 encloses at least one lattice point in addition to the origin. The area bound is sharp: if S is the interior of the square with vertices (±1, ±1) then S is symmetric and convex, and has area 4, but the only lattice point it contains is the origin. This example, showing that the bound of the theorem is sharp, generalizes to hypercubes in every dimension n.

Proof

The following argument proves Minkowski's theorem for the specific case of

Proof of the case: Consider the map

Intuitively, this map cuts the plane into 2 by 2 squares, then stacks the squares on top of each other. Clearly f (S) has area less than or equal to 4, because this set lies within a 2 by 2 square. Assume for a contradiction that f could be injective, which means the pieces of S cut out by the squares stack up in a non-overlapping way. Because f is locally area-preserving, this non-overlapping property would make it area-preserving for all of S, so the area of f (S) would be the same as that of S, which is greater than 4. That is not the case, so the assumption must be false: f is not injective, meaning that there exist at least two distinct points p1, p2 in S that are mapped by f to the same point: f (p1) = f (p2).

Because of the way f was defined, the only way that f (p1) can equal f (p2) is for p2 to equal p1 + (2i, 2j) for some integers i and j, not both zero. That is, the coordinates of the two points differ by two even integers. Since S is symmetric about the origin, −p1 is also a point in S. Since S is convex, the line segment between −p1 and p2 lies entirely in S, and in particular the midpoint of that segment lies in S. In other words,

is a point in S. But this point (i, j) is an integer point, and is not the origin since i and j are not both zero. Therefore, S contains a nonzero integer point.

Remarks:

- The argument above proves the theorem that any set of volume contains two distinct points that differ by a lattice vector. This is a special case of Blichfeldt's theorem.

- The argument above highlights that the term is the covolume of the lattice .

- To obtain a proof for general lattices, it suffices to prove Minkowski's theorem only for ; this is because every full-rank lattice can be written as for some linear transformation , and the properties of being convex and symmetric about the origin are preserved by linear transformations, while the covolume of is and volume of a body scales by exactly under an application of .

Applications

Bounding the shortest vector

Minkowski's theorem gives an upper bound for the length of the shortest nonzero vector. This result has applications in lattice cryptography and number theory.

Theorem (Minkowski's bound on the shortest vector): Let be a lattice. Then there is a with . In particular, by the standard comparison between and norms, .

Let , and set . Then . If , then contains a non-zero lattice point, which is a contradiction. Thus . Q.E.D.

Remarks:

- The constant in the bound can be improved, for instance by taking the open ball of radius as in the above argument. The optimal constant is known as the Hermite constant.

- The bound given by the theorem can be very loose, as can be seen by considering the lattice generated by . But it cannot be further improved in the sense that there exists a global constant such that there exists an -dimensional lattice satisfying for all . Furthermore, such lattice can be self-dual.

- Even though Minkowski's theorem guarantees a short lattice vector within a certain magnitude bound, finding this vector is in general a hard computational problem. Finding the vector within a factor guaranteed by Minkowski's bound is referred to as Minkowski's Vector Problem (MVP), and it is known that approximation SVP reduces to it using transference properties of the dual lattice. The computational problem is also sometimes referred to as HermiteSVP.

- The LLL-basis reduction algorithm can be seen as a weak but efficiently algorithmic version of Minkowski's bound on the shortest vector. This is because a -LLL reduced basis for has the property that ; see these lecture notes of Micciancio for more on this. As explained in, proofs of bounds on the Hermite constant contain some of the key ideas in the LLL-reduction algorithm.

Applications to number theory

Primes that are sums of two squares

The difficult implication in Fermat's theorem on sums of two squares can be proven using Minkowski's bound on the shortest vector.

Theorem: Every prime with can be written as a sum of two squares.

Since and is a quadratic residue modulo a prime if and only if (Euler's Criterion) there is a square root of in ; choose one and call one representative in for it . Consider the lattice defined by the vectors , and let denote the associated matrix. The determinant of this lattice is , whence Minkowski's bound tells us that there is a nonzero with . We have and we define the integers . Minkowski's bound tells us that , and simple modular arithmetic shows that , and thus we conclude that . Q.E.D.