Metamemory or Socratic awareness, a type of metacognition, is both the introspective knowledge of one's own memory capabilities (and strategies that can aid memory) and the processes involved in memory self-monitoring. This self-awareness of memory has important implications for how people learn and use memories. When studying, for example, students make judgments of whether they have successfully learned the assigned material and use these decisions, known as "judgments of learning", to allocate study time.

History

Descartes, among other philosophers, marveled at the phenomenon of what we now know as metacognition. "It was not so much thinking that was indisputable to Descartes, but rather thinking about thinking. What he could not imagine was that the person engaged in such self-reflective processing did not exist." In the late 19th century, Bowne and James contemplated, but did not scientifically examine, the relationship between memory judgments and memory performance.

During the reign of behaviorism in the mid-20th century, unobservable phenomena such as metacognition were largely ignored. One early scientific study of metamemory was Hart's 1965 study, which examined the accuracy of feeling of knowing (FOK). FOK occurs when an individual feels that they have something in memory that cannot be recalled, but would be recognized if seen. Hart expanded upon limited investigations of FOK which had presupposed that FOK was accurate. The results of Hart's study indicate that FOK is indeed a relatively accurate indicator of what is in memory.

In a 1970 review of memory research, Tulving and Madigan concluded that advances in the study of memory might require the experimental investigation of “one of the truly unique characteristics of human memory: its knowledge of its own knowledge”. It was around the same time that John H. Flavell coined the term "metamemory" in a discussion on the development of memory. Since then, numerous metamemory phenomena have been studied, including judgments of learning, feelings of knowing, knowing that you don't know, and know vs. remember.

Nelson and Narens proposed a theoretical framework for understanding metacognition and metamemory. In this framework there are two levels: the object level (for example, cognition and memory) and the meta level (for example, metacognition and metamemory). Information flow from the meta level to the object level is called control, and information flow from the object level to the meta level is called monitoring. Both monitoring and control processes occur in acquisition, retention, and retrieval. Examples of control processes are allocating study time and selecting search strategies, and examples of monitoring processes are ease of learning (EOL) and feeling of knowing (FOK) judgments. Monitoring and control might be further divided into subprocesses depending on the types of inputs, computations, and outputs required at different stages of the memory process. For example, monitoring abilities appear to be sufficiently different during encoding-based and retrieval-based metamemory judgments to constitute different monitoring systems.

The study of metamemory has some similarities to introspection in that it assumes that a memorizer is able to investigate and report on the contents of memory. Current metamemory researchers acknowledge that an individual's introspections contain both accuracies and distortions and are interested in what this conscious monitoring (even if it is not always accurate) reveals about the memory system.

Theories

Cue familiarity hypothesis

The cue familiarity hypothesis was proposed by Reder and Ritter after completing a pair of experiments which indicated that individuals can evaluate their ability to answer a question before trying to answer it. This finding suggests that the question (cue) and not the actual memory (target) is crucial for making metamemory judgments. Consequently, this hypothesis implies that judgments regarding metamemory are based on an individual's level of familiarity with the information provided in the cue. Therefore, an individual is more likely to judge that they know the answer to a question if they are familiar with its topic or terms and more likely to judge that they do not know the answer to a question which presents new or unfamiliar terms.

Accessibility hypothesis

The accessibility hypothesis suggests that memory will be accurate when the ease of processing (accessibility) is correlated with memory behaviour; however, if the ease of processing is not correlated with memory in a given task, then the judgments will not be accurate. Proposed by Koriat, the theory suggests that participants base their judgments on retrieved information rather than basing them on the sheer familiarity of the cues. Along with the lexical unit, people may use partial information that could be correct or incorrect. According to Koriat, the participants themselves do not know whether the information they are retrieving is correct or incorrect most of the time. The quality of information retrieved depends on individual elements of that information. The individual elements of information differ in strength and speed of access to the information. Research by Vigliocco, Antonini, and Garrett (1997) and Miozzo and Caramazza (1997) showed that individuals in a tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) state were able to retrieve partial knowledge (gender) about the unrecalled words, providing strong evidence for the accessibility heuristic.

Competition hypothesis

The competition hypothesis is best described using three principles. The first is that many brain systems are activated by visual input, and the activations by these different inputs compete for processing access. Secondly, competition occurs in multiple brain systems and is integrated amongst these individual systems. Finally, competition can be assessed (using top-down neural priming) based on the relevant characteristics of the object at hand.

More competition, also referred to as more interfering activation, leads to poorer recall when tested. This hypothesis contrasts with the cue-familiarity hypothesis because objects similar to the target can influence one's FOK, not just similar associates of the cues. It also contrasts with the accessibility hypothesis wherein the more accessible information is, the higher the rating, or the better the recall. According to the competition hypothesis, less activation would result in better recall. Whereas the accessibility view predicts higher metamemory ratings in interference conditions, the competition hypothesis predicts lower ratings.

Interactive hypothesis

The interactive hypothesis constitutes a combination of the cue familiarity and accessibility hypotheses. According to this hypothesis, cue familiarity is employed initially, and only once cue familiarity fails to provide enough information to make an inference does accessibility come into play. This "cascade" structure accounts for differences in the time required to make a metamemory judgment; judgments which occur quickly are based on cue familiarity, while slower responses are based on both cue familiarity and accessibility.

Phenomena

Judgment of learning

Judgments of learning (JOLs) or metamemory judgments are made when knowledge is acquired. Metamnemonic judgments are based on different sources of information, and target information is important for JOLs. Intrinsic cues (based on the target information) and mnemonic cues (based on previous JOL performance) are especially important for JOLs. Judgment of learning can be divided into four categories: ease-of-learning judgments, paired-associate JOLs, ease-of-recognition judgments, and free-recall JOLs.

Ease-of-Learning Judgments: These judgments are made before a study trial. Subjects can evaluate how much studying will be required to learn the particular information presented to them (typically cue-target pairs). These judgments can be categorized as preacquisition judgments which are made before the knowledge is stored. Little research addresses this kind of judgment; however, evidence suggests that JOLs are at least somewhat accurate at predicting learning rates. Therefore, these judgments occur in advance of learning and allow individuals to allot study time to the material that they are required to learn.

Paired-Associate Judgment of Learning: These judgments are made at the time of study on cue-target pairs and are responsible for predicting later memory performance (on cued recall or cued recognition). One example of paired-associate JOLs is the cue-target JOL, where the subject determines the retrievability of the target when both the cue and target of the to-be-learned pair are presented. Another example is the cue-only JOL, where the subject must determine the retrievability of the target when only the cue is presented at the time of judgment. These two types of JOLs differ in their accuracy in predicting future performance, and delayed judgments tend to be more accurate.

Ease-of-Recognition Judgments: This type of JOL predicts the likelihood of future recognition. Subjects are given a list of words and asked to make judgments concerning their later ability to recognize these words as old or new in a recognition test. This helps determine their ability to recognize the words after acquisition.

Free-Recall Judgments of Learning: This type of JOL predicts the likelihood of future free-recall. In this situation, subjects assess a single target item and judge the likelihood of later free-recall. It may appear similar to ease-of-recognition judgments, but it predicts recall instead of recognition.

Feeling of knowing judgments

Feeling of Knowing (FOK) judgments refer to the predictions an individual makes of being able to retrieve specific information (i.e., regarding his or her knowledge for a specific subject) and, more specifically, whether that knowledge exists within the person's memory. These judgments are made either prior to the memory target being found or following a failed attempt to locate the target. Consequently, FOK judgments focus not on the actual answer to a question, but rather on whether an individual predicts that he or she does or does not know the answer (high and low FOK ratings respectively). FOK judgments can also be made regarding the likelihood of remembering information later on and have proven to give fairly accurate indications of future memory. An example of FOK is if you can't remember the answer when someone asks you what city you're traveling to, but you feel that you would recognize the name if you saw it on a map of the country.

An individual's FOK judgments are not necessarily accurate, and attributes of all three metamemory hypotheses are apparent in the factors that influence FOK judgments and their accuracy. For example, a person is more likely to give a higher FOK rating (indicating that they do know the answer) when presented with questions they feel they should know the answer to. This is in keeping with the cue familiarity hypothesis, as the familiarity of the question terms influences the individual's judgment. Partial retrieval also impacts FOK judgments, as proposed by the accessibility hypothesis. The accuracy of an FOK judgment is dependent upon the accuracy of the partial information which is retrieved. Consequently, accurate partial information leads to accurate FOK judgments, while inaccurate partial information leads to inaccurate FOK judgments. FOK judgments are also influenced by the number of memory traces linked to the cue. When a cue is linked to fewer memory traces, resulting in a low level of competition, a higher FOK rating is given, thus supporting the competition hypothesis.

Certain physiological states can also influence an individual's FOK judgments. Altitude, for instance, has been shown to reduce FOK judgments, despite having no effect on recall. In contrast, alcohol intoxication results in reduced recall while having no effect on FOK judgments.

Knowing that you do not know

When someone asks a person a question such as "What is your name?", the person automatically knows the answer. However, when someone asks a person a question such as "What was the fifth dinosaur ever discovered?", the person also automatically knows that they do not know the answer.

A person knowing that they do not know is another aspect of metamemory that enables people to respond quickly when asked a question that they do not know the answer to. In other words, people are aware of the fact that they do not know certain information and do not have to go through the process of trying to find the answer within their memories, since they know the information in question will never be remembered. One theory as to why this knowledge of not knowing is so rapidly retrieved is consistent with the cue-familiarity hypothesis. The cue familiarity hypothesis states that metamemory judgments are made based on the familiarity of the information presented in the cue. The more familiar the information in the memory cue, the more likely a person will make the judgment that they know that the target information is in memory. With regards to knowing that you don't know, if the memory cue information does not elicit any familiarity, then a person quickly judges that the information is not stored in memory.

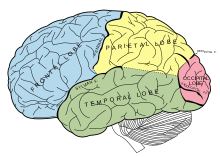

The right ventral prefrontal cortex and the insular cortex are specific to "knowing that you don't know", whereas prefrontal regions are generally more specific to the feeling of knowing. These findings suggest that a person knowing that they do not know and feeling of knowing are two neuroanatomically dissociable features of metamemory. As well, "knowing that you don't know" relies more on cue familiarity than feeling of knowing does.

There are two basic types of "do not know" decisions. First is a slow, low confidence decision. This occurs when a person has some knowledge relevant to the question asked. This knowledge is located and evaluated to determine whether the question can be answered based on what is stored in memory. In this case, the relevant knowledge is not enough to answer the question. Second, when a person has zero knowledge relevant to a question asked, they are able to produce a rapid response of not knowing. This occurs because the initial search for information draws a blank and the search stops, thus producing a faster response.

Remember vs. know

The quality of information that is recalled can vary greatly depending on the information being remembered. It is important to understand the differences between remembering something and knowing something. If information about the learning context accompanies a memory (i.e. the setting), it is called a "remember" experience. However, if a person does not consciously remember the context in which he or she learned a particular piece of information and only has the feeling of familiarity towards it, it is called a "know" experience. It is widely believed that recognition has two underlying processes: recollection and familiarity. The recollection process retrieves memories from one's past and can elicit any number of associations of the prior experience ("remember"). In contrast, the familiarity process does not elicit associations with the memory and there are no contextual details of the prior learning occurrence ("know"). Since these two processes are dissociable, they can be affected by different variables (i.e. when remember is affected know is not and vice versa). For example, "remember" is affected by variables such as depth of processing, generation effects, the frequency of occurrence, divided attention at learning, and reading silently vs. aloud. In contrast, "know" is affected by repetition priming, stimulus modality, amount of maintenance rehearsal, and suppression of focal attention. There are cases however, where "remember" and "know" are both affected, but in opposite ways. An example of this would be if "remember" responses are more common than "know" responses. This can occur due to word versus nonword memory, massed versus distributed practice, gradual versus abrupt presentations, and learning in a way that emphasizes similarities vs. differences.

Another aspect of the "remember" versus "know" phenomenon is hindsight bias, also referred to as the "knew it all along effect". This occurs when a person believes that an event is more deterministic after it has happened. That is, in the face of the outcome of a situation, people tend to overestimate the quality of their previous knowledge, thus leading the person to a distortion towards the provided information. Some researchers believe that the original information gets distorted by the new information at the time of encoding. The term "creeping determinism" is used to emphasize the fact that it is completely natural for one to integrate outcome information with the original information to create an appropriate whole out of all the pertinent information. Although it was found that informing individuals about the hindsight bias before they took part in experiments did not decrease the bias, it is possible to avoid the effects of the hindsight bias. Further, by discrediting the outcome knowledge, people are better able to accurately retrieve their original knowledge state, therefore reducing the hindsight bias.

Errors in being able to differentiate between ‘remembering’ versus ‘knowing’ can be attributed to a phenomenon known as source monitoring. This is a framework where one tries to identify the context or source from which a particular memory or event has arisen. This is more prevalent with information that is ‘known’ rather than ‘remembered’.

Prospective memory

It is important to be able to keep track of future intentions and plans, and most importantly, individuals need to remember to actually carry out such intentions and plans. This memory for future events is prospective memory. Prospective memory includes forming the intention to carry out a particular task in the future, which action we’re going to use to carry out the action, and when we want to do it. Thus, prospective memory is in use continuously in day-to-day life. For example, prospective memory is in use when you decide that you need to write and send a letter to a friend.

There are two types of prospective memory; event-based and time based. Event-based prospective memory is when an environmental cue prompts you to carry out a task. An example is when seeing a friend reminds you to ask him a question. In contrast, time-based prospective memory occurs when you remember to carry out a task at a specific time. An example of this is remembering to phone your sister on her birthday. Time-based prospective memory is more difficult than event-based prospective memory because there is no environmental cue prompting one to remember to carry out the task at that specific time.

In some cases, impairments to prospective memory can have dire consequences. If an individual with diabetes cannot remember to take their medication, they might face serious health consequences. Prospective memory also generally gets worse with age, but the elderly can implement strategies to improve prospective memory performance.

Improving memory

Mnemonics

A mnemonic is "a word, sentence, or picture device or technique for improving or strengthening memory". Information learnt through mnemonics makes use of a form of deep processing: elaborative encoding. It uses mnemonic tools such as imagery in order to encode specific information with the goal of creating an association between the tool and the information. This leads to the information becoming more accessible and therefore leads to better retention. One example of a mnemonic is the method of loci, in which the memorizer associates each to be remembered item with a different well-known location. Then, during retrieval, the memorizer "strolls" along the locations and remembers each related item. Other types of mnemonic tools including the creating acronyms, the drawing effect (which states drawing something increases the likelihood of remembering it), chunking and organisation and imagery (where you associate images with the information you are trying to remember).

The application of a mnemonic is intentional, suggesting that in order to successfully use a mnemonic device an individual should be aware that the mnemonic can aid his or her memory. Awareness of how a mnemonic facilitates one's memory is an example of metamemory. Wimmer and Tornquist conducted an experiment in which participants were asked to recall a set of items. Participants were made aware of the usefulness of a mnemonic device (categorical grouping) either before or after recall. Participants who were made aware of the usefulness of the mnemonic before recall (displaying metamemory for the mnemonic's usefulness) were significantly more likely to use the mnemonic than those who were not made aware of the mnemonic before recall.

Exceptional memory

Mnemonists are people with exceptional memory. These individuals have seemingly effortless memories and perform tasks that may seem challenging to the general population. They seem to have beyond normal abilities to encode and retrieve information. There is strong evidence suggesting that exceptional performance is acquired, rather than it being a natural ability, and that "ordinary" people can improve their memory drastically with the use of appropriate practice and strategies such as mnemonics. However it is important to acknowledge that although sometimes these well developed tools increase memorisation capabilities in general, more often than not, mnemonists tend to have one domain they specialise in. In other words, one strategy doesn't work for all sorts of memorisations. Because metamemory is important for the selection and application of strategies, it is also important for the improvement of memory.

There are a number of mnemonists who specialise in different areas of memory and make use of different strategies to do so. For example, Ericsson et al. conducted a study with an undergraduate student "S.F." who had an initial digit span of 7 (within the normal range). This means that, on average, he was able to recall sequences of 7 random numbers after they were presented. Following more than 230 hours of practice, S.F. was able to increase his digit span to 79. S.F.'s use of mnemonics was essential. He used race times, ages, and dates to categorize the numbers, creating mnemonic associations.

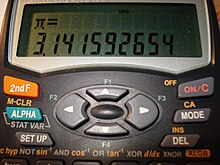

Another example of a mnemonist is Suresh Kumar Sharma, who holds the world record for reciting the most digits of pi (70,030).

Brain-imaging conducted by Tanaka et al. reveals that subjects with exceptional performance activate some brain regions that are different from those activated by control participants. Some memory performance tasks in which people display exceptional memory are chess, medicine, auditing, computer programming, bridge, physics, sports, typing, juggling, dance, and music.

Physiological influences

Neurological disorders

In a review of research on patients with various neurological disorders, Pannu et al. found that metamemory was affected by various neurological disorders, including Korsakoff's amnesia, frontal lobe injury, multiple sclerosis and HIV. Other disorders, such as temporal lobe epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, and traumatic brain injury had mixed results, and disorders such as Parkinson's syndrome and Huntington's syndrome showed no effect.

In their review, Pannu and Kaszniak reached 4 conclusions:

(1) There is a strong correlation between indices of frontal lobe function or structural integrity and metamemory accuracy (2) The combination of frontal lobe dysfunction and poor memory severely impairs metamemorial processes (3) Metamemory tasks vary in subject performance levels, and quite likely, in the underlying processes these different tasks measure, and (4) Metamemory, as measured by experimental tasks, may dissociate from basic memory retrieval processes and from global judgments of memory.

Frontal lobe injury

Neurobiological research of metamemory is in its early stages, but recent evidence suggests that the frontal lobe is involved. A study of patients with medial prefrontal cortex damage showed that feeling-of-knowing judgments and memory confidence were lower than in controls.

Studies suggest that right frontal lobe, especially the medial frontal area, is important for metamemory. Damage to this area is associated with impaired metamemory, especially for weak memory traces and effortful episodic tasks.

Korsakoff's syndrome

Individuals with Korsakoff's syndrome, the result of thiamine deficiency in chronic alcoholics, have damage to the dorsomedial nucleus of the thalamus and the mammillary nuclei, as well as degeneration of the frontal lobes. They display both amnesia and poor metamemory. Shimamura and Squire found that while patients with Korsakoff's syndrome displayed impaired FOK judgments, other amnesic patients did not.

HIV

Pannu and Kaszniak found that patients with HIV had impaired metamemory. However, a later study focusing on HIV found that this impairment was primarily caused by the general fatigue associated with the disease.

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) causes demyelination of the central nervous system. One study found that individuals with MS displayed impaired metamemory for tasks that required high monitoring, but metamemory for easier tasks was not impaired.

Other disorders

Individuals with temporal lobe epilepsy display impaired metamemory for some tasks and not for others, but little research has been conducted in this area.

One of the characteristics of Alzheimer's disease (AD) is decreased memory performance, but there are inconclusive results regarding metamemory in AD. Metamemory impairment is commonly observed in individuals late in the progression of AD, and some studies also find metamemory impairment early in AD, while others do not.

Individuals with either Parkinson's disease or Huntington's disease do not appear to have impaired metamemory.

Maturation

In general, metamemory improves as children mature, but even preschoolers can display accurate metamemory. There are three areas of metamemory that improve with age. 1) Declarative metamemory – As children mature they gain knowledge of memory strategies. 2) Self-control – As children mature they generally become better at allocating study time. 3) Self-monitoring – Older children are better than younger children at JOL and EOL judgments. Children can be taught to improve their metamemory through instruction programs at school. Research suggests that children with ADHD may fall behind in the development of metamemory as preschoolers.

In a recent study on metacognition, measures of metamemory (such as study time allocation) and executive function were found to decline with age. This contradicts earlier studies, which showed no decline when metamemory was dissociated from other forms of memory and even suggested that metamemory could improve with age.

In a cross-sectional study, it was found that the confidence people have in the accuracy of their memory remains relatively constant across age groups, despite the memory impairment that occurs in other forms of memory in the elderly. This is likely the reason why the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon becomes more common with age.

Pharmacology

In a study of self-reported effects of MDMA (ecstasy) on metamemory, metamemory variables such as memory-related feelings/beliefs and self-reported memory were examined. Results suggest that drug use may cause retrospective memory failures. Although other factors such as high anxiety levels of drug users might contribute to memory failure, drug use can impair metamemory abilities. Further, research has shown that benzodiazepine lorazepam has effects on metamemory. When studying four-letter nonsense words, persons on benzodiazepine lorazepam displayed impaired episodic short-term memory and lower FOK estimates. However, benzodiazepine lorazepam did not affect the predictive accuracy of FOK judgments.

Metamemory in non-humans

Metamemory has also been researched in non-humans. As it is impossible to administer the questionnaires used in human trials, non-human trials are performed using a Match-to-sample task, such as Hampton's use of delayed matching-to-sample (DMTS) tasks with Rhesus monkeys.

There is also evidence that metamemory can be created in AI technologies. Sudo et al. used DMTS and reported that computational agents controlled by artificial neural networks could evolve metamemory ability. Similarly, despite starting from random neural networks that did not even have a memory function, a model created by researchers at Nagoya University was able to evolve to the point that it performed DMTS similarly to monkeys. They reported that the neural network could examine its memories, keep them, and separate outputs without requiring any assistance or intervention by the researchers, suggesting the plausibility of it having metamemory mechanisms.