The ideal gas law, also called the general gas equation, is the equation of state of a hypothetical ideal gas. It is a good approximation of the behavior of many gases under many conditions, although it has several limitations. It was first stated by Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron in 1834 as a combination of the empirical Boyle's law, Charles's law, Avogadro's law, and Gay-Lussac's law. The ideal gas law is often written in an empirical form:

where , and are the pressure, volume and temperature respectively; is the amount of substance; and is the ideal gas constant. It can also be derived from the microscopic kinetic theory, as was achieved (apparently independently) by August Krönig in 1856 and Rudolf Clausius in 1857.

Equation

The state of an amount of gas is determined by its pressure, volume, and temperature. The modern form of the equation relates these simply in two main forms. The temperature used in the equation of state is an absolute temperature: the appropriate SI unit is the kelvin.

Common forms

The most frequently introduced forms are:where:

- is the absolute pressure of the gas,

- is the volume of the gas,

- is the amount of substance of gas (also known as number of moles),

- is the ideal, or universal, gas constant, equal to the product of the Boltzmann constant and the Avogadro constant,

- is the Boltzmann constant,

- is the Avogadro constant,

- is the absolute temperature of the gas,

- is the number of particles (usually atoms or molecules) of the gas.

In SI units, p is measured in pascals, V is measured in cubic metres, n is measured in moles, and T in kelvins (the Kelvin scale is a shifted Celsius scale, where 0 K = −273.15 °C, the lowest possible temperature). R has for value 8.314 J/(mol·K) = 1.989 ≈ 2 cal/(mol·K), or 0.0821 L⋅atm/(mol⋅K).

Molar form

How much gas is present could be specified by giving the mass instead of the chemical amount of gas. Therefore, an alternative form of the ideal gas law may be useful. The chemical amount, n (in moles), is equal to total mass of the gas (m) (in kilograms) divided by the molar mass, M (in kilograms per mole):

By replacing n with m/M and subsequently introducing density ρ = m/V, we get:

Defining the specific gas constant Rspecific as the ratio R/M,

This form of the ideal gas law is very useful because it links pressure, density, and temperature in a unique formula independent of the quantity of the considered gas. Alternatively, the law may be written in terms of the specific volume v, the reciprocal of density, as

It is common, especially in engineering and meteorological applications, to represent the specific gas constant by the symbol R. In such cases, the universal gas constant is usually given a different symbol such as or to distinguish it. In any case, the context and/or units of the gas constant should make it clear as to whether the universal or specific gas constant is being used.

Statistical mechanics

In statistical mechanics, the following molecular equation (i.e. the ideal gas law in its theoretical form) is derived from first principles:

where p is the absolute pressure of the gas, n is the number density of the molecules (given by the ratio n = N/V, in contrast to the previous formulation in which n is the number of moles), T is the absolute temperature, and kB is the Boltzmann constant relating temperature and energy, given by:

where NA is the Avogadro constant. The form can be further simplified by defining the kinetic energy corresponding to the temperature:

so the ideal gas law is more simply expressed as:

From this we notice that for a gas of mass m, with an average particle mass of μ times the atomic mass constant, mu, (i.e., the mass is μ Da) the number of molecules will be given by

and since ρ = m/V = nμmu, we find that the ideal gas law can be rewritten as

In SI units, p is measured in pascals, V in cubic metres, T in kelvins, and kB = 1.38×10−23 J⋅K−1 in SI units.

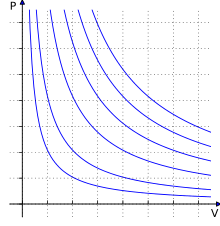

Combined gas law

Combining the laws of Charles, Boyle and Gay-Lussac gives the combined gas law, which takes the same functional form as the ideal gas law says that the number of moles is unspecified, and the ratio of to is simply taken as a constant:

where is the pressure of the gas, is the volume of the gas, is the absolute temperature of the gas, and is a constant. When comparing the same substance under two different sets of conditions, the law can be written as

Energy associated with a gas

According to the assumptions of the kinetic theory of ideal gases, one can consider that there are no intermolecular attractions between the molecules, or atoms, of an ideal gas. In other words, its potential energy is zero. Hence, all the energy possessed by the gas is the kinetic energy of the molecules, or atoms, of the gas.

This corresponds to the kinetic energy of n moles of a monoatomic gas having 3 degrees of freedom; x, y, z. The table here below gives this relationship for different amounts of a monoatomic gas.

| Energy of a monoatomic gas | Mathematical expression |

|---|---|

| Energy associated with one mole | |

| Energy associated with one gram | |

| Energy associated with one atom |

Applications to thermodynamic processes

The table below essentially simplifies the ideal gas equation for a particular process, making the equation easier to solve using numerical methods.

A thermodynamic process is defined as a system that moves from state 1 to state 2, where the state number is denoted by a subscript. As shown in the first column of the table, basic thermodynamic processes are defined such that one of the gas properties (P, V, T, S, or H) is constant throughout the process.

For a given thermodynamic process, in order to specify the extent of a particular process, one of the properties ratios (which are listed under the column labeled "known ratio") must be specified (either directly or indirectly). Also, the property for which the ratio is known must be distinct from the property held constant in the previous column (otherwise the ratio would be unity, and not enough information would be available to simplify the gas law equation).

In the final three columns, the properties (p, V, or T) at state 2 can be calculated from the properties at state 1 using the equations listed.

| Process | Constant | Known ratio or delta | p2 | V2 | T2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isobaric process | Pressure | V2/V1 | p2 = p1 | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1) |

| T2/T1 | p2 = p1 | V2 = V1(T2/T1) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | ||

| Isochoric process (Isovolumetric process) (Isometric process) |

Volume | p2/p1 | p2 = p1(p2/p1) | V2 = V1 | T2 = T1(p2/p1) |

| T2/T1 | p2 = p1(T2/T1) | V2 = V1 | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | ||

| Isothermal process | Temperature | p2/p1 | p2 = p1(p2/p1) | V2 = V1(p1/p2) | T2 = T1 |

| V2/V1 | p2 = p1(V1/V2) | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1 | ||

| Isentropic process (Reversible adiabatic process) |

p2/p1 | p2 = p1(p2/p1) | V2 = V1(p2/p1)(−1/γ) | T2 = T1(p2/p1)(γ − 1)/γ | |

| V2/V1 | p2 = p1(V2/V1)−γ | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1)(1 − γ) | ||

| T2/T1 | p2 = p1(T2/T1)γ/(γ − 1) | V2 = V1(T2/T1)1/(1 − γ) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | ||

| Polytropic process | P Vn | p2/p1 | p2 = p1(p2/p1) | V2 = V1(p2/p1)(−1/n) | T2 = T1(p2/p1)(n − 1)/n |

| V2/V1 | p2 = p1(V2/V1)−n | V2 = V1(V2/V1) | T2 = T1(V2/V1)(1 − n) | ||

| T2/T1 | p2 = p1(T2/T1)n/(n − 1) | V2 = V1(T2/T1)1/(1 − n) | T2 = T1(T2/T1) | ||

| Isenthalpic process (Irreversible adiabatic process) |

p2 − p1 | p2 = p1 + (p2 − p1) |

|

T2 = T1 + μJT(p2 − p1) | |

| T2 − T1 | p2 = p1 + (T2 − T1)/μJT |

|

T2 = T1 + (T2 − T1) |

^ a. In an isentropic process, system entropy (S) is constant. Under these conditions, p1V1γ = p2V2γ, where γ is defined as the heat capacity ratio, which is constant for a calorifically perfect gas. The value used for γ is typically 1.4 for diatomic gases like nitrogen (N2) and oxygen (O2), (and air, which is 99% diatomic). Also γ is typically 1.6 for mono atomic gases like the noble gases helium (He), and argon (Ar). In internal combustion engines γ varies between 1.35 and 1.15, depending on constitution gases and temperature.

^ b. In an isenthalpic process, system enthalpy (H) is constant. In the case of free expansion for an ideal gas, there are no molecular interactions, and the temperature remains constant. For real gasses, the molecules do interact via attraction or repulsion depending on temperature and pressure, and heating or cooling does occur. This is known as the Joule–Thomson effect. For reference, the Joule–Thomson coefficient μJT for air at room temperature and sea level is 0.22 °C/bar.

Deviations from ideal behavior of real gases

The equation of state given here (PV = nRT) applies only to an ideal gas, or as an approximation to a real gas that behaves sufficiently like an ideal gas. There are in fact many different forms of the equation of state. Since the ideal gas law neglects both molecular size and intermolecular attractions, it is most accurate for monatomic gases at high temperatures and low pressures. The neglect of molecular size becomes less important for lower densities, i.e. for larger volumes at lower pressures, because the average distance between adjacent molecules becomes much larger than the molecular size. The relative importance of intermolecular attractions diminishes with increasing thermal kinetic energy, i.e., with increasing temperatures. More detailed equations of state, such as the van der Waals equation, account for deviations from ideality caused by molecular size and intermolecular forces.

Derivations

Empirical

The empirical laws that led to the derivation of the ideal gas law were discovered with experiments that changed only 2 state variables of the gas and kept every other one constant.

All the possible gas laws that could have been discovered with this kind of setup are:

- Boyle's law (Equation 1)

- Charles's law (Equation 2)

- Avogadro's law (Equation 3)

- Gay-Lussac's law (Equation 4)

- Equation 5

- Equation 6

where P stands for pressure, V for volume, N for number of particles in the gas and T for temperature; where are constants in this context because of each equation requiring only the parameters explicitly noted in them changing.

To derive the ideal gas law one does not need to know all 6 formulas, one can just know 3 and with those derive the rest or just one more to be able to get the ideal gas law, which needs 4.

Since each formula only holds when only the state variables involved in said formula change while the others (which are a property of the gas but are not explicitly noted in said formula) remain constant, we cannot simply use algebra and directly combine them all. This is why: Boyle did his experiments while keeping N and T constant and this must be taken into account (in this same way, every experiment kept some parameter as constant and this must be taken into account for the derivation).

Keeping this in mind, to carry the derivation on correctly, one must imagine the gas being altered by one process at a time (as it was done in the experiments). The derivation using 4 formulas can look like this:

at first the gas has parameters

Say, starting to change only pressure and volume, according to Boyle's law (Equation 1), then:

| 7 |

After this process, the gas has parameters

Using then equation (5) to change the number of particles in the gas and the temperature,

| 8 |

After this process, the gas has parameters

Using then equation (6) to change the pressure and the number of particles,

| 9 |

After this process, the gas has parameters

Using then Charles's law (equation 2) to change the volume and temperature of the gas,

| 10 |

After this process, the gas has parameters

Using simple algebra on equations (7), (8), (9) and (10) yields the result: or where stands for the Boltzmann constant.

Another equivalent result, using the fact that , where n is the number of moles in the gas and R is the universal gas constant, is: which is known as the ideal gas law.

If three of the six equations are known, it may be possible to derive the remaining three using the same method. However, because each formula has two variables, this is possible only for certain groups of three. For example, if you were to have equations (1), (2) and (4) you would not be able to get any more because combining any two of them will only give you the third. However, if you had equations (1), (2) and (3) you would be able to get all six equations because combining (1) and (2) will yield (4), then (1) and (3) will yield (6), then (4) and (6) will yield (5), as well as would the combination of (2) and (3) as is explained in the following visual relation:

where the numbers represent the gas laws numbered above.

If you were to use the same method used above on 2 of the 3 laws on the vertices of one triangle that has a "O" inside it, you would get the third.

For example:

Change only pressure and volume first:

| 1' |

then only volume and temperature:

| 2' |

then as we can choose any value for , if we set , equation (2') becomes:

| 3' |

combining equations (1') and (3') yields , which is equation (4), of which we had no prior knowledge until this derivation.

Theoretical

Kinetic theory

The ideal gas law can also be derived from first principles using the kinetic theory of gases, in which several simplifying assumptions are made, chief among which are that the molecules, or atoms, of the gas are point masses, possessing mass but no significant volume, and undergo only elastic collisions with each other and the sides of the container in which both linear momentum and kinetic energy are conserved.

First we show that the fundamental assumptions of the kinetic theory of gases imply that

Consider a container in the Cartesian coordinate system. For simplicity, we assume that a third of the molecules moves parallel to the -axis, a third moves parallel to the -axis and a third moves parallel to the -axis. If all molecules move with the same velocity , denote the corresponding pressure by . We choose an area on a wall of the container, perpendicular to the -axis. When time elapses, all molecules in the volume moving in the positive direction of the -axis will hit the area. There are molecules in a part of volume of the container, but only one sixth (i.e. a half of a third) of them moves in the positive direction of the -axis. Therefore, the number of molecules that will hit the area when the time elapses is .

When a molecule bounces off the wall of the container, it changes its momentum to . Hence the magnitude of change of the momentum of one molecule is . The magnitude of the change of momentum of all molecules that bounce off the area when time elapses is then . From and we get

We considered a situation where all molecules move with the same velocity . Now we consider a situation where they can move with different velocities, so we apply an "averaging transformation" to the above equation, effectively replacing by a new pressure and by the arithmetic mean of all squares of all velocities of the molecules, i.e. by Therefore

which gives the desired formula.

Using the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution, the fraction of molecules that have a speed in the range to is , where

and denotes the Boltzmann constant. The root-mean-square speed can be calculated by

Using the integration formula

it follows that

from which we get the ideal gas law:

Statistical mechanics

Let q = (qx, qy, qz) and p = (px, py, pz) denote the position vector and momentum vector of a particle of an ideal gas, respectively. Let F denote the net force on that particle. Then (two times) the time-averaged kinetic energy of the particle is:

where the first equality is Newton's second law, and the second line uses Hamilton's equations and the equipartition theorem. Summing over a system of N particles yields

By Newton's third law and the ideal gas assumption, the net force of the system is the force applied by the walls of the container, and this force is given by the pressure P of the gas. Hence

where dS is the infinitesimal area element along the walls of the container. Since the divergence of the position vector q is

the divergence theorem implies that

where dV is an infinitesimal volume within the container and V is the total volume of the container.

Putting these equalities together yields

which immediately implies the ideal gas law for N particles:

where n = N/NA is the number of moles of gas and R = NAkB is the gas constant.

Other dimensions

For a d-dimensional system, the ideal gas pressure is:

where is the volume of the d-dimensional domain in which the gas exists. The dimensions of the pressure changes with dimensionality.