Economic history is the study of history using methodological tools from economics or with a special attention to economic phenomena. Research is conducted using a combination of historical methods, statistical methods and the application of economic theory to historical situations and institutions. The field can encompass a wide variety of topics, including equality, finance, technology, labour, and business. It emphasizes historicizing the economy itself, analyzing it as a dynamic entity and attempting to provide insights into the way it is structured and conceived.

Using both quantitative data and qualitative sources, economic historians emphasize understanding the historical context in which major economic events take place. They often focus on the institutional dynamics of systems of production, labor, and capital, as well as the economy's impact on society, culture, and language. Scholars of the discipline may approach their analysis from the perspective of different schools of economic thought, such as mainstream economics, Austrian economics, Marxian economics, the Chicago school of economics, and Keynesian economics.

Economic history has several sub-disciplines. Historical methods are commonly applied in financial and business history, which overlap with areas of social history such as demographic and labor history. In the sub-discipline of cliometrics, economists use quantitative (econometric) methods. In history of capitalism, historians explain economic historical issues and processes from a historical point of view.

Early history of the discipline

Arnold Toynbee made the case for combining economics and history in his study of the Industrial Revolution, saying, "I believe economics today is much too dissociated from history. Smith and Malthus had historical minds. However, Ricardo – who set the pattern of modern textbooks – had a mind that was entirely unhistorical." There were several advantages in combining economics and history according to Toynbee. To begin with, it improved economic understanding. "We see abstract propositions in a new light when studying them in relation to historical facts. Propositions become more vivid and truthful." Meanwhile, studying history with economics makes history easier to understand. Economics teaches us to look out for the right facts in reading history and makes matters such as introducing enclosures, machinery, or new currencies more intelligible. Economics also teaches careful deductive reasoning. "The habits of mind it instils are even more valuable than the knowledge of principles it gives. Without these habits, the mass of their materials can overwhelm students of historical facts."

In late-nineteenth-century Germany, scholars at a number of universities, led by Gustav von Schmoller, developed the historical school of economic history. It argued that there were no universal truths in history, emphasizing the importance of historical context without quantitative analysis. This historical approach dominated German and French scholarship for most of the 20th century. The historical school of economics included other economists such as Max Weber and Joseph Schumpeter who reasoned that careful analysis of human actions, cultural norms, historical context, and mathematical support was key to historical analysis. The approach was spread to Great Britain by William Ashley (University of Oxford) and dominated British economic history for much of the 20th century. Britain's first professor in the subject was George Unwin at the University of Manchester. Meanwhile, in France, economic history was heavily influenced by the Annales School from the early 20th century to the present. It exerts a worldwide influence through its journal Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales.

Treating economic history as a discrete academic discipline has been a contentious issue for many years. Academics at the London School of Economics (LSE) and the University of Cambridge had numerous disputes over the separation of economics and economic history in the interwar era. Cambridge economists believed that pure economics involved a component of economic history and that the two were inseparably entangled. Those at the LSE believed that economic history warranted its own courses, research agenda and academic chair separated from mainstream economics. In the initial period of the subject's development, the LSE position of separating economic history from economics won out. Many universities in the UK developed independent programmes in economic history rooted in the LSE model. Indeed, the Economic History Society had its inauguration at LSE in 1926 and the University of Cambridge eventually established its own economic history programme.

In the United States, the field of economic history was largely subsumed into other fields of economics following the cliometric revolution of the 1960s. To many it became seen as a form of applied economics rather than a stand-alone discipline. Cliometrics, also known as the New Economic History, refers to the systematic use of economic theory and econometric techniques to the study of economic history. The term was originally coined by Jonathan R. T. Hughes and Stanley Reiter and refers to Clio, who was the muse of history and heroic poetry in Greek mythology. One of the most famous cliometric economic historians is Douglass North, who argued that it is the task of economic history to elucidate the historical dimensions of economies through time. Cliometricians argue their approach is necessary because the application of theory is crucial in writing solid economic history, while historians generally oppose this view warning against the risk of generating anachronisms.

Early cliometrics was a type of counterfactual history. However, counterfactualism was not its distinctive feature; it combined neoclassical economics with quantitative methods in order to explain human choices based on constraints. Some have argued that cliometrics had its heyday in the 1960s and 1970s and that it is now neglected by economists and historians. In response to North and Robert Fogel's Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics in 1993, Harvard University economist (and future Nobel winner) Claudia Goldin argued:

Economic history is not a handmaiden of economics but a distinct field of scholarship. Economic history was a scholarly discipline long before it became cliometrics. Its practitioners were economists and historians studying the histories of economies... The new economic history, or cliometrics, formalized economic history in a manner similar to the injection of mathematical models and statistics into the rest of economics.

The relationship between economic history, economics and history has long been the subject of intense discussion, and the debates of recent years echo those of early contributors. There has long been a school of thought among economic historians that splits economic history—the study of how economic phenomena evolved in the past—from historical economics—testing the generality of economic theory using historical episodes. US economic historian Charles P. Kindleberger explained this position in his 1990 book Historical Economics: Art or Science?. Economic historian Robert Skidelsky (University of Cambridge) argued that economic theory often employs ahistorical models and methodologies that do not take into account historical context. Yale University economist Irving Fisher already wrote in 1933 on the relationship between economics and economic history in his "Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions":

The study of dis-equilibrium may proceed in either of two ways. We may take as our unit for study an actual historical case of great dis-equilibrium, such as, say, the panic of 1873; or we may take as our unit for study any constituent tendency, such as, say, deflation, and discover its general laws, relations to, and combinations with, other tendencies. The former study revolves around events, or facts; the latter, around tendencies. The former is primarily economic history; the latter is primarily economic science. Both sorts of studies are proper and important. Each helps the other. The panic of 1873 can only be understood in light of the various tendencies involved—deflation and other; and deflation can only be understood in the light of various historical manifestations—1873 and other.

Scope and focus of economic history today

The past three decades have witnessed the widespread closure of separate economic history departments and programmes in the UK and the integration of the discipline into either history or economics departments. Only the London School of Economics (LSE) retains a separate economic history department and stand-alone undergraduate and graduate programme in economic history. Cambridge, Glasgow, LSE, Oxford, Queen's, and Warwick together train the vast majority of economic historians coming through the British higher education system today, but do so as part of economics or history degrees. Meanwhile, there have never been specialist economic history graduate programs at universities anywhere in the US. However, economic history remains a special field component of leading economics PhD programs, including University of California, Berkeley, Harvard University, Northwestern University, Princeton University, the University of Chicago and Yale University.

Despite the pessimistic view on the state of the discipline espoused by many of its practitioners, economic history remains an active field of social scientific inquiry. Indeed, it has seen something of a resurgence in interest since 2000, perhaps driven by research conducted at universities in continental Europe rather than the UK and the US. The overall number of economic historians in the world is estimated at 10,400, with Japan and China as well as the U.K and the U.S. ranking highest in numbers. Some less developed countries, however, are not sufficiently integrated in the world economic history community, among others, Senegal, Brazil and Vietnam.

Part of the growth in economic history is driven by the continued interest in big policy-relevant questions on the history of economic growth and development. MIT economist Peter Temin noted that development economics is intricately connected with economic history, as it explores the growth of economies with different technologies, innovations, and institutions. Studying economic growth has been popular for years among economists and historians who have sought to understand why some economies have grown faster than others. Some of the early texts in the field include Walt Whitman Rostow's The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (1971) which described how advanced economies grow after overcoming certain hurdles and advancing to the next stage in development. Another economic historian, Alexander Gerschenkron, complicated this theory with works on how economies develop in non-Western countries, as discussed in Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective: A Book of Essays (1962). A more recent work is Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson's Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012) which pioneered a new field of persistence studies, emphasizing the path-dependent stages of growth. Other notable books on the topic include Kenneth Pomeranz's The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (2000) and David S. Landes's The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some are So Rich and Some So Poor (1998).

Since the 2008 financial crisis, scholars have become more interested in a field which may be called new 'new economic history'. Scholars have tended to move away from narrowly quantitative studies toward institutional, social, and cultural history affecting the evolution of economies. The focus of these studies is frequently on "persistence", as past events are linked to present outcomes. Columbia University economist Charles Calomiris argued that this new field showed 'how historical (path-dependent) processes governed changes in institutions and markets.' However, this trend has been criticized, most forcefully by Francesco Boldizzoni, as a form of economic imperialism "extending the neoclassical explanatory model to the realm of social relations."

Conversely, economists in other specializations have started to write a new kind of economic history which makes use of historical data to understand the present day. A major development in this genre was the publication of Thomas Piketty's Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013). The book described the rise in wealth and income inequality since the 18th century, arguing that large concentrations of wealth lead to social and economic instability. Piketty also advocated a system of global progressive wealth taxes to correct rising inequality. The book was selected as a New York Times best seller and received numerous awards. The book was well received by some of the world's major economists, including Paul Krugman, Robert Solow, and Ben Bernanke. Books in response to Piketty's book include After Piketty: The Agenda for Economics and Inequality, by Heather Boushey, J. Bradford DeLong, and Marshall Steinbaum (eds.) (2017), Pocket Piketty by Jesper Roine (2017), and Anti-Piketty: Capital for the 21st Century, by Jean-Philippe Delsol, Nicolas Lecaussin, Emmanuel Martin (2017). One economist argued that Piketty's book was "Nobel-Prize worthy" and noted that it had changed the global discussion on how economic historians study inequality. It has also sparked new conversations in the disciplines of public policy.

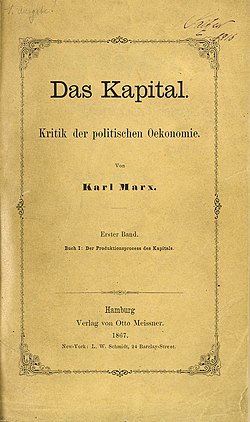

In addition to the mainstream in economic history, there is a parallel development in the field influenced by Karl Marx and Marxian economics. Marx used historical analysis to interpret the role of class and class as a central issue in history. He debated with the "classical" economists (a term he coined), including Adam Smith and David Ricardo. In turn, Marx's legacy in economic history has been to critique the findings of neoclassical economists. Marxist analysis also confronts economic determinism, the theory that economic relationships are the foundation of political and societal institutions. Marx abstracted the idea of a "capitalist mode of production" as a way of identifying the transition from feudalism to capitalism. This has influenced some scholars, such as Maurice Dobb, to argue that feudalism declined because of peasants' struggles for freedom and the growing inefficiency of feudalism as a system of production. In turn, in what was later coined the Brenner debate, Paul Sweezy, a Marxian economist, challenged Dobb's definition of feudalism and its focus only on western Europe.

History of capitalism

A new field, called "history of capitalism" by researchers engaged in it, has emerged in US history departments since about the year 2000. It includes many topics traditionally associated with the field of economic history, such as insurance, banking and regulation, the political dimension of business, and the impact of capitalism on the middle classes, the poor and women and minorities. The field has particularly focused on the contribution of slavery to the rise of the US economy in the nineteenth century. The field utilizes the existing research of business history, but has sought to make it more relevant to the concerns of history departments in the United States, including by having limited or no discussion of individual business enterprises. Historians of capitalism have countered these critiques, citing the issues with economic history. As University of Chicago professor of history Jonathan Levy states, "modern economic history began with industrialization and urbanization, and, even then, environmental considerations were subsidiary, if not nonexistent."

Scholars have critiqued the history of capitalism because it does not focus on systems of production, circulation, and distribution. Some have criticized its lack of social scientific methods and its ideological biases. As a result, a new academic journal, Capitalism: A Journal of History and Economics, was founded at the University of Pennsylvania under the direction of Marc Flandreau (University of Pennsylvania), Julia Ott (The New School, New York) and Francesca Trivellato (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton) to widen the scope of the field. The journal's goal is to bring together "historians and social scientists interested in the material and intellectual aspects of modern economic life."

Academic journals and societies

The first journal specializing in the field of economic history was The Economic History Review, founded in 1927, as the main publication of the Economic History Society. The first journal featured a publication by Professor Sir William Ashley, the first Professor of Economic History in the English-speaking world, who described the emerging field of economic history. The discipline existed alongside long-standing fields such as political history, religious history, and military history as one that focused on humans' interactions with 'visible happenings'. He continued, '[economic history] primarily and unless expressly extended, the history of actual human practice with respect to the material basis of life. The visible happenings with regard-to use the old formula-to "the production, distribution, and consumption of wealth" form our wide enough field'.

Later, the Economic History Association established another academic journal, The Journal of Economic History, in 1941 as a way of expanding the discipline in the United States. The first president of the Economic History Association, Edwin F. Gay, described the aim of economic history as to provide new perspectives in the economics and history disciplines: 'An adequate equipment with two skills, that of the historian and the economist, is not easily acquired, but experience shows that it is both necessary and possible'. Other related academic journals have broadened the lens with which economic history is studied. These interdisciplinary journals include the Business History Review, European Review of Economic History, Enterprise and Society, and Financial History Review.

The International Economic History Association, an association of close to 50 member organizations, recognizes some of the major academic organizations dedicated to study of economic history: the Business History Conference, Economic History Association, Economic History Society, European Association of Business Historians, and the International Social History Association.

Nobel Memorial Prize-winning economic historians

Have a very healthy respect for the study of economic history, because that's the raw material out of which any of your conjectures or testings will come.

– Paul Samuelson (2009)

Several economists have won Nobel prizes for contributions to economic history or contributions to economics that are commonly applied in economic history.

- Simon Kuznets won the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences ("the Nobel Memorial Prize") in 1971 "for his empirically founded interpretation of economic growth which has led to new and deepened insight into the economic and social structure and process of development".

- John Hicks, whose early writing was on the field of economic history, won the Nobel Memorial Prize in 1972 due to his contributions to general equilibrium theory and welfare theory.

- Arthur Lewis won the Nobel Memorial Prize in 1979 for his contributions in the field of economic development through historical context.

- Milton Friedman won the Nobel Memorial Prize in 1976 for "his achievements in the fields of consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and for his demonstration of the complexity of stabilization policy".

- Robert Fogel and Douglass North won the Nobel Memorial Prize in 1993 for "having renewed research in economic history by applying economic theory and quantitative methods in order to explain economic and institutional change".

- Claudia Goldin, who won the Nobel in 2023 for 'having advanced our understanding of women's labor market outcomes', began her career researching the history of the US southern economy and was President of the Economic History Association in 1999/2000.

Notable works of economic history

Foundational works

- Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867–1960 (1963)

- Friedrich Hayek, The Road to Serfdom (1944)

- Karl Marx, Capital: A Critique of Political Economy (1867)

- Karl Polanyi, The Great Transformation: Origins of Our Time (1944)

- David Ricardo, On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation (1817)

- Adam Smith, An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776)

General

- Robert C. Allen, Global Economic History: A Very Short Introduction (2011)

- Gregory Clark, A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World (2007)

- Ronald Findlay and Kevin O’Rourke, Power and Plenty: Trade, War, and the World Economy in the Second Millennium (2007)

- Robert Heilbroner, The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times and Ideas of the Great Economic Thinkers (1953)

- Eric Roll, A History of Economic Thought (1923)

Ancient economies

- Moses Finley, The Ancient Economy (1973)

- Walter Scheidel, The Great Leveler: Violence and the History of Inequality from the Stone Age to the Twenty-First Century (2017)

- Peter Temin, The Roman Market Economy (2012)

Economic growth and development

- Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty (2012)

- Alexander Gerschenkron, Economic Backwardness in Historical Perspective: A Book of Essays (1962)

- Robert J. Gordon, The Rise and Fall of American Growth: The U.S. Standard of Living Since the Civil War (2016)

- David S. Landes, The Wealth and Poverty of Nations: Why Some are So Rich and Some So Poor (1998)

- Deirdre McCloskey, Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions, Enriched the World (2016)

- Joel Mokyr, The Lever of Riches: Technological Creativity and Economic Progress (1990)

- Kenneth Pomeranz, The Great Divergence: China, Europe, and the Making of the Modern World Economy (2000)

- Walt Whitman Rostow, The Stages of Economic Growth: A Non-Communist Manifesto (1971)

- Jeffrey Sachs, The End of Poverty: Economic Possibilities for Our Time (2005)

- Amartya Sen, Development as Freedom (1999)

- William Easterly, The White Man's Burden: Why the West's Efforts to Aid the Rest Have Done So Much Ill and So Little Good] (2006)

History of money

- Christine Desan, Making Money: Coin, Currency, and the Coming of Capitalism (2014)

- William N. Goetzmann, Money Changes Everything: How Finance Made Civilization Possible (2016)

- David Graeber, Debt: The First 5000 Years (2011)

Business history

- David Cannadine, Mellon: An American Life (2006)

- Alfred D. Chandler Jr., The Visible Hand: The Managerial Revolution in American Business (1977)

- Ron Chernow, The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance (1990)

- Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr. (1998)

- William D. Cohan, Money and Power: How Goldman Sachs Came to Rule the World

- Naomi Lamoreaux, The Great Merger Movement in American Business, 1895–1904 (1985)

- David Nasaw, Andrew Carnegie (2006)

- Jean Strouse, Morgan: American Financier (1999)

Financial history

- Liaquat Ahamed, Lords of Finance: The Bankers Who Broke the World (2009)

- Mark Blyth, Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea (2013)

- Charles W. Calomiris and Stephen H. Haber, Fragile by Design: The Political Origins of Banking Crises and Scarce Credit (2014)

- Barry Eichengreen, Exorbitant Privilege: The Rise and Fall of the Dollar and the Future of the International Monetary System (2010)

- Barry Eichengreen, Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System (1996)

- Niall Ferguson, The Ascent of Money: A Financial History of the World (2008)

- Harold James, International Monetary Cooperation Since Bretton Woods (1996)

- Carmen M. Reinhart and Kenneth S. Rogoff, This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly (2009)

- Benn Steil, The Battle of Bretton Woods: John Maynard Keynes, Harry Dexter White, and the Making of a New World Order (2013)

- Adam Tooze, The Wages of Destruction: The Making and Breaking of the Nazi Economy (2006)

- László Vértesy, Financial Perspectives of Economic History (2024) Volume I, Volume II

Globalization and inequality

- Sven Beckert, Empire of Cotton: A Global History (2014)

- William J. Bernstein, A Splendid Exchange: How Trade Shaped the World from Prehistory to Today (2008).

- Niall Ferguson, The Cash Nexus: Money and Power in the Modern World, 1700-2000 (2001).

- Robert Fogel and Stanley L. Engerman, Time on the Cross: The Economics of American Negro Slavery (1974).

- Claudia Goldin, Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American Women (1990).

- Harold James, The End of Globalization: Lessons from the Great Depression (2009).

- Kevin O'Rourke and Jeffrey G. Williamson, Globalization and History: The Evolution of a Nineteenth-century Atlantic Economy (1999)

- Thomas Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century (2013).

- Thomas Piketty, The Economics of Inequality (2015).

- Thomas Piketty, Capital and Ideology (2020).

- Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman, The Triumph of Injustice: How the Rich Dodge Taxes and How to Make Them Pay (2019).

- Gabriel Zucman, The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens (2015).