In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the Tenth Amendment. The enumerated powers that are listed in the Constitution include exclusive federal powers, as well as concurrent powers that are shared with the states, and all of those powers are contrasted with the reserved powers—also called states' rights—that only the states possess.

Background

Text

The Supremacy Clause of the U.S. Constitution states:This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all treaties made, or which shall be made, under the authority of the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and the judges in every state shall be bound thereby, anything in the constitution or laws of any state to the contrary notwithstanding. (Emphasis added.)In The Federalist Papers, ratification proponent Alexander Hamilton explained the limitations this clause placed on the proposed federal government, describing that acts of the federal government were binding on the states and the people therein only if the act was in pursuance of constitutionally granted powers, and juxtaposing acts which exceeded those bounds as "void and of no force":

But it will not follow from this doctrine that acts of the large society which are not pursuant to its constitutional powers, but which are invasions of the residuary authorities of the smaller societies, will become the supreme law of the land. These will be merely acts of usurpation, and will deserve to be treated as such.

Controversy to 1865

In the period between the American Revolution and the ratification of the United States Constitution, the states had united under a much weaker federal government and a much stronger state and local government, pursuant to the Articles of Confederation. The Articles gave the central government very little, if any, authority to overrule individual state actions. The Constitution subsequently strengthened the central government, authorizing it to exercise powers deemed necessary to exercise its authority, with an ambiguous boundary between the two co-existing levels of government. In the event of any conflict between state and federal law, the Constitution resolved the conflict via the Supremacy Clause of Article VI in favor of the federal government, which declares federal law the "supreme Law of the Land" and provides that "the Judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any Thing in the Constitution or Laws of any State to the Contrary notwithstanding." However, the Supremacy Clause only applies if the federal government is acting in pursuit of its constitutionally authorized powers, as noted by the phrase "in pursuance thereof" in the actual text of the Supremacy Clause itself (see above).Alien and Sedition Acts

When the Federalists passed the Alien and Sedition Acts in 1798, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison secretly wrote the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which provide a classic statement in support of states' rights and called on state legislatures to nullify unconstitutional federal laws. (The other states, however, did not follow suit and several rejected the notion that states could nullify federal law.) According to this theory, the federal union is a voluntary association of states, and if the central government goes too far each state has the right to nullify that law. As Jefferson said in the Kentucky Resolutions:Resolved, that the several States composing the United States of America, are not united on the principle of unlimited submission to their general government; but that by compact under the style and title of a Constitution for the United States and of amendments thereto, they constituted a general government for special purposes, delegated to that government certain definite powers, reserving each State to itself, the residuary mass of right to their own self-government; and that whensoever the general government assumes undelegated powers, its acts are unauthoritative, void, and of no force: That to this compact each State acceded as a State, and is an integral party, its co-States forming, as to itself, the other party....each party has an equal right to judge for itself, as well of infractions as of the mode and measure of redress.The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which became part of the Principles of '98, along with the supporting Report of 1800 by Madison, became final documents of Jefferson's Democratic-Republican Party. Gutzman argued that Governor Edmund Randolph designed the protest in the name of moderation. Gutzman argues that in 1798, Madison espoused states' rights to defeat national legislation that he maintained was a threat to republicanism. During 1831–33, the South Carolina Nullifiers quoted Madison in their defense of states' rights. But Madison feared that the growing support for this doctrine would undermine the union and argued that by ratifying the Constitution states had transferred their sovereignty to the federal government.

The most vociferous supporters of states' rights, such as John Randolph of Roanoke, were called "Old Republicans" into the 1820s and 1830s.

Tate (2011) undertook a literary criticism of a major book by John Taylor of Caroline, New Views of the Constitution of the United States. Tate argues it is structured as a forensic historiography modeled on the techniques of 18th-century Whig lawyers. Taylor believed that evidence from American history gave proof of state sovereignty within the union, against the arguments of nationalists such as U.S. Chief Justice John Marshall.

Another states' rights dispute occurred over the War of 1812. At the Hartford Convention of 1814–15, New England Federalists voiced opposition to President Madison's war, and discussed secession from the Union. In the end they stopped short of calls for secession, but when their report appeared at the same time as news of the great American victory at the Battle of New Orleans, the Federalists were politically ruined.

Nullification Crisis of 1832

One major and continuous strain on the union, from roughly 1820 through the Civil War, was the issue of trade and tariffs. Heavily dependent upon international trade, the almost entirely agricultural and export-oriented South imported most of its manufactured goods from Europe or obtained them from the North. The North, by contrast, had a growing domestic industrial economy that viewed foreign trade as competition. Trade barriers, especially protective tariffs, were viewed as harmful to the Southern economy, which depended on exports.In 1828, the Congress passed protective tariffs to benefit trade in the northern states, but that were detrimental to the South. Southerners vocally expressed their tariff opposition in documents such as the South Carolina Exposition and Protest in 1828, written in response to the "Tariff of Abominations." Exposition and Protest was the work of South Carolina senator and former vice president John C. Calhoun, formerly an advocate of protective tariffs and internal improvements at federal expense.

South Carolina's Nullification Ordinance declared that both the tariff of 1828 and the tariff of 1832 were null and void within the state borders of South Carolina. This action initiated the Nullification Crisis. Passed by a state convention on November 24, 1832, it led, on December 10, to President Andrew Jackson's proclamation against South Carolina, which sent a naval flotilla and a threat of sending federal troops to enforce the tariffs; Jackson authorized this under color of national authority, claiming in his 1832 Proclamation Regarding Nullification that "our social compact in express terms declares, that the laws of the United States, its Constitution, and treaties made under it, are the supreme law of the land" and for greater caution adds, "that the judges in every State shall be bound thereby, anything in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary notwithstanding."

Civil War

Over the following decades, another central dispute over states' rights moved to the forefront. The issue of slavery polarized the union, with the Jeffersonian principles often being used by both sides—anti-slavery Northerners, and Southern slaveholders and secessionists—in debates that ultimately led to the American Civil War. Supporters of slavery often argued that one of the rights of the states was the protection of slave property wherever it went, a position endorsed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1857 Dred Scott decision. In contrast, opponents of slavery argued that the non-slave-states' rights were violated both by that decision and by the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850. Exactly which—and whose—states' rights were the casus belli in the Civil War remain in controversy.Southern arguments

A major Southern argument in the 1850s was that banning slavery in the territories discriminated against states that allowed slavery, making them second-class states. In 1857 the Supreme Court sided with the states' rights supporters, declaring in Dred Scott v. Sandford that Congress had no authority to regulate slavery in the territories.Jefferson Davis used the following argument in favor of the equal rights of states:

Resolved, That the union of these States rests on the equality of rights and privileges among its members, and that it is especially the duty of the Senate, which represents the States in their sovereign capacity, to resist all attempts to discriminate either in relation to person or property, so as, in the Territories—which are the common possession of the United States—to give advantages to the citizens of one State which are not equally secured to those of every other State.Southern states sometimes argued against 'states rights'. For example, Texas challenged some northern states having the right to protect fugitive slaves.

Economists such as Thomas DiLorenzo and Charles Adams argue that the Southern secession and the ensuing conflict was much more of a fiscal quarrel than a war over slavery. Northern-inspired tariffs benefited Northern interests but were detrimental to Southern interests and were destroying the economy in the South. These tariffs would be less subject to states rights' arguments.

Northern arguments

The historian James McPherson noted that Southerners were inconsistent on the states' rights issue, and that Northern states tried to protect the rights of their states against the South during the Gag Rule and fugitive slave law controversies.The historian William H. Freehling noted that the South's argument for a state's right to secede was different from Thomas Jefferson's, in that Jefferson based such a right on the unalienable equal rights of man. The South's version of such a right was modified to be consistent with slavery, and with the South's blend of democracy and authoritarianism. Historian Henry Brooks Adams explains that the anti-slavery North took a consistent and principled stand on states' rights against federal encroachment throughout its history, while the Southern states, whenever they saw an opportunity to expand slavery and the reach of the slave power, often conveniently forgot the principle of states' rights—and fought in favor of federal centralization:

Between the slave power and states' rights there was no necessary connection. The slave power, when in control, was a centralizing influence, and all the most considerable encroachments on states' rights were its acts. The acquisition and admission of Louisiana; the Embargo; the War of 1812; the annexation of Texas "by joint resolution" [rather than treaty]; the war with Mexico, declared by the mere announcement of President Polk; the Fugitive Slave Law; the Dred Scott decision—all triumphs of the slave power—did far more than either tariffs or internal improvements, which in their origin were also southern measures, to destroy the very memory of states' rights as they existed in 1789. Whenever a question arose of extending or protecting slavery, the slaveholders became friends of centralized power, and used that dangerous weapon with a kind of frenzy. Slavery in fact required centralization in order to maintain and protect itself, but it required to control the centralized machine; it needed despotic principles of government, but it needed them exclusively for its own use. Thus, in truth, states' rights were the protection of the free states, and as a matter of fact, during the domination of the slave power, Massachusetts appealed to this protecting principle as often and almost as loudly as South Carolina.Sinha and Richards both argue that the south only used states' rights when they disagreed with a policy. Examples given are a states' right to engage in slavery or to suppress freedom of speech. They argue that it was instead the result of the increasing cognitive dissonance in the minds of Northerners and (some) Southern non-slaveowners between the ideals that the United States was founded upon and identified itself as standing for, as expressed in the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution of the United States, and the Bill of Rights, and the reality that the slave-power represented, as what they describe as an anti-democratic, counter-republican, oligarchic, despotic, authoritarian, if not totalitarian, movement for ownership of human beings as the personal chattels of the slaver. As this cognitive dissonance increased, the people of the Northern states, and the Northern states themselves, became increasingly inclined to resist the encroachments of the slave power upon their states' rights and encroachments of the slave power by and upon the federal government of the United States. The slave power, having failed to maintain its dominance of the federal government through democratic means, sought other means of maintaining its dominance of the federal government, by means of military aggression, by right of force and coercion, and thus, the Civil War occurred.

Texas v. White

In Texas v. White, 74 U.S. 700 (1869) the Supreme Court ruled that Texas had remained a state ever since it first joined the Union, despite claims to have joined the Confederate States of America; the court further held that the Constitution did not permit states to unilaterally secede from the United States, and that the ordinances of secession, and all the acts of the legislatures within seceding states intended to give effect to such ordinances, were "absolutely null" under the constitution.Since the Civil War

A series of Supreme Court decisions developed the state action constraint on the Equal Protection Clause. The state action theory weakened the effect of the Equal Protection Clause against state governments, in that the clause was held not to apply to unequal protection of the laws caused in part by complete lack of state action in specific cases, even if state actions in other instances form an overall pattern of segregation and other discrimination. The separate but equal theory further weakened the effect of the Equal Protection Clause against state governments.In case law

With United States v. Cruikshank (1876), a case which arose out of the Colfax Massacre of blacks contesting the results of a Reconstruction era election, the Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment did not apply to the First Amendment or Second Amendment to state governments in respect to their own citizens, only to acts of the federal government. In McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010), the Supreme Court held that the Second Amendment right of an individual to "keep and bear arms" is incorporated by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and therefore fully applicable to states and local governments.Furthermore, United States v. Harris (1883) held that the Equal Protection Clause did not apply to an 1883 prison lynching on the basis that the Fourteenth Amendment applied only to state acts, not to individual criminal actions.

In the Civil Rights Cases (1883), the Supreme Court allowed segregation by striking down the Civil Rights Act of 1875, a statute that prohibited racial discrimination in public accommodation. It again held that the Equal Protection Clause applied only to acts done by states, not to those done by private individuals, and as the Civil Rights Act of 1875 applied to private establishments, the Court said, it exceeded congressional enforcement power under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Later progressive era and World War II

By the beginning of the 20th century, greater cooperation began to develop between the state and federal governments and the federal government began to accumulate more power. Early in this period, a federal income tax was imposed, first during the Civil War as a war measure and then permanently with the Sixteenth Amendment in 1913. Before this, the states played a larger role in government.States' rights were affected by the fundamental alteration of the federal government resulting from the Seventeenth Amendment, depriving state governments of an avenue of control over the federal government via the representation of each state's legislature in the U.S. Senate. This change has been described by legal critics as the loss of a check and balance on the federal government by the states.

Following the Great Depression, the New Deal and then World War II saw further growth in the authority and responsibilities of the federal government. The case of Wickard v. Filburn allowed the federal government to enforce the Agricultural Adjustment Act, providing subsidies to farmers for limiting their crop yields, arguing agriculture affected interstate commerce and came under the jurisdiction of the Commerce Clause even when a farmer grew his crops not to be sold, but for his own private use.

After World War II, President Harry Truman supported a civil rights bill and desegregated the military. The reaction was a split in the Democratic Party that led to the formation of the "States' Rights Democratic Party"—better known as the Dixiecrats—led by Strom Thurmond. Thurmond ran as the States' Rights candidate for President in the 1948 election, losing to Truman.

Civil rights movement

During the 1950s and 1960s, the Civil Rights Movement was confronted by the proponents in the Southern states of racial segregation and Jim Crow laws who denounced federal interference in these state-level laws as an assault on states' rights.Though Brown v. Board of Education (1954) overruled the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) decision, the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments were largely inactive in the South until the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 21) and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Several states passed Interposition Resolutions to declare that the Supreme Court's ruling in Brown usurped states' rights.

There was also opposition by states' rights advocates to voting rights at Edmund Pettus Bridge, which was part of the Selma to Montgomery marches, that resulted in the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Contemporary debates

In 1964, the issue of fair housing in California involved the boundary between state laws and federalism. California Proposition 14 overturned the Rumsford Fair Housing Act in California and allowed discrimination in any type of housing sale or rental. Martin Luther King, Jr. and others saw this as a backlash against civil rights. Actor Ronald Reagan gained popularity by supporting Proposition 14, and was later elected governor of California. The U.S. Supreme Court's Reitman v. Mulkey decision overturned Proposition 14 in 1967 in favor of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.Conservative historians Thomas E. Woods, Jr. and Kevin R. C. Gutzman argue that when politicians come to power they exercise all the power they can get, in the process trampling states' rights. Gutzman argues that the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions of 1798 by Jefferson and Madison were not only responses to immediate threats but were legitimate responses based on the long-standing principles of states' rights and strict adherence to the Constitution.

Another concern is the fact that on more than one occasion, the federal government has threatened to withhold highway funds from states which did not pass certain articles of legislation. Any state which lost highway funding for any extended period would face financial impoverishment, infrastructure collapse or both. Although the first such action (the enactment of a national speed limit) was directly related to highways and done in the face of a fuel shortage, most subsequent actions have had little or nothing to do with highways and have not been done in the face of any compelling national crisis. An example of this would be the federally mandated drinking age of 21, upheld in South Dakota v. Dole. Critics of such actions feel that when the federal government does this they upset the traditional balance between the states and the federal government.

More recently, the issue of states' rights has come to a head when the Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC) recommended that Congress and the Department of Defense implement sweeping changes to the National Guard by consolidating some Guard installations and closing others. These recommendations in 2005 drew strong criticism from many states, and several states sued the federal government on the basis that Congress and the Pentagon would be violating states' rights should they force the realignment and closure of Guard bases without the prior approval of the governors from the affected states. After Pennsylvania won a federal lawsuit to block the deactivation of the 111th Fighter Wing of the Pennsylvania Air National Guard, defense and Congressional leaders chose to try to settle the remaining BRAC lawsuits out of court, reaching compromises with the plaintiff states.

Current states' rights issues include the death penalty, assisted suicide, same-sex marriage, gun control, and cannabis, the last of which is in direct violation of federal law. In Gonzales v. Raich, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the federal government, permitting the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to arrest medical marijuana patients and caregivers. In Gonzales v. Oregon, the Supreme Court ruled the practice of physician-assisted suicide in Oregon is legal. In Obergefell v. Hodges, the Supreme Court ruled that states could not withhold recognition to same-sex marriages. In District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), the United States Supreme Court ruled that gun ownership is an individual right under the Second Amendment of the United States Constitution, and the District of Columbia could not completely ban gun ownership by law-abiding private citizens. Two years later, the court ruled that the Heller decision applied to states and territories via the Second and 14th Amendments in McDonald v. Chicago, stating that states, territories and political divisions thereof, could not impose total bans on gun ownership by law-abiding citizens.

These concerns have led to a movement sometimes called the State Sovereignty movement or "10th Amendment Sovereignty Movement".

Some, such as former representative Ron Paul (R-TX), have proposed repealing the 17th Amendment of the United States Constitution.

10th Amendment Resolutions

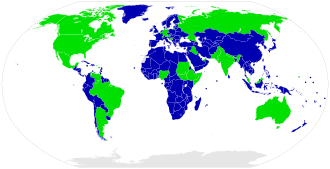

In 2009–2010 thirty-eight states introduced resolutions to reaffirm the principles of sovereignty under the Constitution and the 10th Amendment; 14 states have passed the resolutions. These non-binding resolutions, often called "state sovereignty resolutions" do not carry the force of law. Instead, they are intended to be a statement to demand that the federal government halt its practices of assuming powers and imposing mandates upon the states for purposes not enumerated by the Constitution.States' rights and the Rehnquist Court

The Supreme Court's University of Alabama v. Garrett (2001) and Kimel v. Florida Board of Regents (2000) decisions allowed states to use a rational basis review for discrimination against the aged and disabled, arguing that these types of discrimination were rationally related to a legitimate state interest, and that no "razorlike precision" was needed." The Supreme Court's United States v. Morrison (2000) decision limited the ability of rape victims to sue their attackers in federal court. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist explained that "States historically have been sovereign" in the area of law enforcement, which in the Court's opinion required narrow interpretations of the Commerce Clause and Fourteenth Amendment.Kimel, Garrett and Morrison indicated that the Court's previous decisions in favor of enumerated powers and limits on Congressional power over the states, such as United States v. Lopez (1995), Seminole Tribe v. Florida (1996) and City of Boerne v. Flores (1997) were more than one time flukes. In the past, Congress relied on the Commerce Clause and the Equal Protection Clause for passing civil rights bills, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Lopez limited the Commerce Clause to things that directly affect interstate commerce, which excludes issues like gun control laws, hate crimes, and other crimes that affect commerce but are not directly related to commerce. Seminole reinforced the "sovereign immunity of states" doctrine, which makes it difficult to sue states for many things, especially civil rights violations. The Flores "congruence and proportionality" requirement prevents Congress from going too far in requiring states to comply with the Equal Protection Clause, which replaced the ratchet theory advanced in Katzenbach v. Morgan (1966). The ratchet theory held that Congress could ratchet up civil rights beyond what the Court had recognized, but that Congress could not ratchet down judicially recognized rights. An important precedent for Morrison was United States v. Harris (1883), which ruled that the Equal Protection Clause did not apply to a prison lynching because the state action doctrine applies Equal Protection only to state action, not private criminal acts. Since the ratchet principle was replaced with the "congruence and proportionality" principle by Flores, it was easier to revive older precedents for preventing Congress from going beyond what Court interpretations would allow. Critics such as Associate Justice John Paul Stevens accused the Court of judicial activism (i.e., interpreting law to reach a desired conclusion).

The tide against federal power in the Rehnquist court was stopped in the case of Gonzales v. Raich, 545 U.S. 1 (2005), in which the court upheld the federal power to prohibit medicinal use of cannabis even if states have permitted it. Rehnquist himself was a dissenter in the Raich case.

States' rights as code word

Since the 1940s, the term "states' rights" has often been considered a loaded term because of its use in opposition to federally mandated racial desegregation and more recently, same-sex marriage.During the heyday of the civil rights movement, defenders of segregation used the term "states' rights" as a code word—in what is now referred to as dog-whistle politics—political messaging that appears to mean one thing to the general population but has an additional, different or more specific resonance for a targeted subgroup. In 1948 it was the official name of the "Dixiecrat" party led by white supremacist presidential candidate Strom Thurmond. Democratic governor George Wallace of Alabama, who famously declared in his inaugural address in 1963, "Segregation now! Segregation tomorrow! Segregation forever!"—later remarked that he should have said, "States' rights now! States' rights tomorrow! States' rights forever!" Wallace, however, claimed that segregation was but one issue symbolic of a larger struggle for states' rights; in that view, which some historians dispute, his replacement of segregation with states' rights would be more of a clarification than a euphemism.

In 2010, Texas governor Rick Perry's use of the expression "states' rights", to some, was reminiscent of "an earlier era when it was a rallying cry against civil rights." During an interview with The Dallas Morning News, Perry made it clear that he supports the end of segregation, including passage of the Civil Rights Act. Texas president of the NAACP Gary Bledsoe stated that he understood that Perry wasn't speaking of "states' rights" in a racial context; but others still felt offended by the term because of its past misuse.