A superhabitable world is a hypothetical type of planet or moon that is better suited than Earth for the emergence and evolution of life. The concept was introduced in a 2014 paper by René Heller and John Armstrong, in which they criticized the language used in the search for habitable exoplanets and proposed clarifications. The authors argued that knowing whether a world is located within the star's habitable zone is insufficient to determine its habitability, that the principle of mediocrity cannot adequately explain why Earth should represent the archetypal habitable world, and that the prevailing model of characterization was geocentric or anthropocentric in nature. Instead, they proposed a biocentric approach that prioritized astrophysical characteristics affecting the abundance and variety of life on a world's surface.

If a world possesses more diverse flora and fauna than there are on Earth, then it would empirically show that its natural environment is more hospitable to life. To identify such a world, one should consider its geological processes, formation age, atmospheric composition, ocean coverage, and the type of star that it orbits. In other words, a superhabitable world would likely be larger, warmer, and older than Earth, with an evenly-distributed ocean, and orbiting a K-type main-sequence star. In 2020, astronomers, building on Heller and Armstrong's hypothesis, identified 24 potentially superhabitable exoplanets based on measured characteristics that fit these criteria.

Stellar characteristics

A star's characteristics is a key consideration for planetary habitability. The types of stars generally considered to be potential hosts for habitable worlds include F, G, K, and M-type main-sequence stars. The most massive stars—O, B, and A-type, respectively—have average lifespans on the main sequence that are considered too short for complex life to develop, ranging from a few hundred million years for A-type stars to only a few million years for O-type stars. Thus, F-type stars are described as the "hot limit" for stars that can potentially support life, as their lifespan of 2 to 4 billion years would be sufficient for habitability. However, F-type stars emit large amounts of ultraviolet radiation, and without the presence of a protective ozone layer, could disrupt nucleic acid-based life on a planet's surface.

On the opposite end, the less massive red dwarfs, which generally includes M-type stars, are by far the most common and long-lived stars in the universe, but ongoing research points to serious challenges to their ability to support life. Due to the low luminosity of red dwarfs, the circumstellar habitable zone (HZ) is in very close proximity to the star, which causes any planet to become tidally locked. The primary concern for researchers, however, is the star's propensity for frequent outbreaks of high-energy radiation, especially early in its life, that could strip away a planet's atmosphere. At the same time, red dwarfs do not emit enough quiescent UV radiation (i.e., UV radiation emitted during inactive periods) to support biological processes like photosynthesis.

Dismissing both ends, G and K-type stars—yellow and orange dwarfs, respectively—have been primary objects of interest for astronomers because they are seen to provide the best life-supporting characteristics. However, Heller and Armstrong argue that a limiting factor to the habitability of yellow dwarfs is their higher emissions of quiescent UV radiation compared to cooler orange dwarfs. For this reason, along with the shorter lifespan of yellow dwarfs, the authors are led to conclude that orange dwarfs offer the best conditions for a superhabitable world. Also nicknamed "Goldilocks stars," orange dwarfs emit low enough levels of ultraviolet radiation to eliminate the need for a protective ozone layer, but just enough to contribute to necessary biological processes. Moreover, the long average lifespan of an orange dwarf (18 to 34 billion years, compared to 10 billion for the Sun) provides stable habitable zones that do not move very much throughout the star's lifetime.

Planetary characteristics

Age

The age of a superhabitable world should be greater than Earth's age (~4.5 billion years). This is based on the belief that as a planet ages, it experiences increasing levels of biodiversity, since native species have had more time to evolve, adapt, and stabilize the environmental conditions suitable for life. As for the maximum age, research points to rocky planets existing as early as 12 billion years ago.

It was initially believed that since older stars contained little to no heavy elements (i.e., metallicity), they were incapable of forming rocky planets. Early exoplanet discoveries supported this hypothesis, as they were mostly gas giants orbiting in close proximity to stars with a heavy metal abundance. However, in 2012, the Kepler space telescope challenged this assumption when it discovered many rocky exoplanets orbiting stars with a relatively low metallicity. These findings suggested that the first Earth-sized planets likely appeared much earlier in the universe's lifetime at around 12 billion years ago.

Orbit and rotation

During the main sequence phase, a star burns hydrogen in its core, producing energy through nuclear fusion. Over time, as the hydrogen fuel is consumed, the star's core contracts and heats up, leading to an increase in the rate of fusion. This causes the star to gradually become more luminous, and as its luminosity increases, the amount of energy it emits grows, pushing the habitable zone (HZ) outward. Because a main sequence star's luminosity gradually increases throughout its life, its HZ is not static but slowly moves outward. This means that any planet will experience a limited time within the HZ, known as its "habitable zone lifetime." Studies suggest that Earth's orbit lies near the inner edge of the Solar System's HZ, which could harm its long-term livability as it nears the end of its HZ lifetime.

Ideally, the orbit of a superhabitable world should be further out and closer to the center of the HZ relative to Earth's orbit, but knowing whether a world is in this region is insufficient on its own to determine habitability. Not all rocky planets in the HZ may be habitable, while tidal heating can render planets or moons habitable beyond this region. For example, Jupiter's moon Europa is well beyond the outer limits of the Solar System's HZ, yet as a result of its orbital interactions with the other Galilean moons, it is believed to have a subsurface ocean of liquid water beneath its icy surface.

There is no consensus on the optimal rotation rate for habitability, but a planet's rotation can affect the presence of geologically-active plate tectonics and the generation of a global magnetic field.

According to a 2023 paper by Jonathan Jernigan and colleagues, marine biological activity increases on planets with increasing obliquity and eccentricity. The authors suggest that planets with a high obliquity and/or eccentricity may be superhabitable, and that scientists should be keen to look for biosignatures on exoplanets with these orbital characteristics.

Mass and size

Assuming that a greater surface area would provide greater biodiversity, the size of a superhabitable world should generally be greater than 1 R🜨, with the condition that its mass is not arbitrarily large. Studies of the mass-radius relationship indicate that there is a transition point between rocky planets and gaseous planets (i.e., mini-Neptunes) that occurs around 2 M🜨 or 1.7 R🜨. Another study argues that there is a natural radius limit, set at 1.6 R🜨, below which nearly all planets are terrestrial, composed primarily of rock-iron-water mixtures.

Heller and Armstrong argue that the optimal mass and radius of a superhabitable world can be determined by geological activity; the more massive a planetary body, the longer time it will continuously generate internal heat—a major contributing factor to plate tectonics. Too much mass, however, can slow plate tectonics by increasing the pressure of the mantle. It is believed that plate tectonics peak in bodies between 1 and 5 M🜨, and from this perspective, a planet can be considered superhabitable up to around 2 M🜨. Assuming this planet has a density similar to Earth's, its radius should be between 1.2 and 1.3 R🜨.

Geology

An important geological process is plate tectonics, which appears to be common in terrestrial planets with a significant rotation speed and an internal heat source. If large bodies of water are present on a planet, plate tectonics can maintain high levels of carbon dioxide (CO

2) in its atmosphere and increase the global surface temperature through the greenhouse effect. However, if tectonic activity is not significant enough to increase temperatures above the freezing point of water, the planet could experience a permanent ice age, unless the process is offset by another energy source like tidal heating or stellar irradiation.

On the other hand, if the effects of any of these processes are too

strong, the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere could cause a runaway greenhouse effect by trapping heat and preventing adequate cooling.

The presence of a magnetic field is important for the long-term survivability of life on the surface of a planet or moon. A sufficiently strong magnetic field effectively shields a world's surface and atmosphere against ionizing radiation emanating from the interstellar medium and its host star. A planet can generate an intrinsic magnetic field through a dynamo that involves an internal heat source, an electrically conductive fluid like molten iron, and a significant rotation speed, while a moon could be extrinsically protected by its host planet's magnetic field. Less massive bodies and those that are tidally locked are likely to have a weak to non-existent magnetic field, which over time can result in the loss of a significant portion of its atmosphere by hydrodynamic escape and become a desert planet. If a planet's rotation is too slow, such as with Venus, then it cannot generate an Earth-like magnetic field. A more massive planet could overcome this problem by hosting multiple moons, which through their combined gravitational effects, can boost the planet's magnetic field.

Surface features

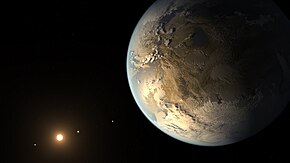

The appearance of a superhabitable world should be similar to the conditions found in the tropical climates of Earth. Due to the denser atmosphere and less temperature variation across its surface, such a world would lack any major ice sheets and have a higher concentration of clouds, while plant life would potentially cover more of the planet's surface and be visible from space.

When considering the differences in the peak wavelength of visible light for K-type stars and the lower stellar flux of the planet, surface vegetation may exhibit colors different than the typical green color found on Earth. Instead, vegetation on these worlds could have a red, orange, or even purple appearance.

An ocean that covers a large portion of a world's surface with fractionate continents and archipelagos could provide a stable environment across its surface. In addition, the greater surface gravity of a superhabitable world could reduce the average ocean depth and create shallow ocean basins, providing the optimal environment for marine life to thrive. For example, marine ecosystems found in the shallow areas of Earth's oceans and seas, given the amount of light and heat they receive, are observed to have greater biodiversity and are generally seen as being more comfortable for aquatic species. This has led researchers to speculate that shallow water environments on exoplanets should be similarly suitable for life.

Climate

In general, the climate of a superhabitable planet would be warm, moist, and homogeneous, allowing life to extend across the surface without presenting large population differences. These characteristics are in contrast to those found on Earth, which has more variable and inhospitable regions that include frigid tundra and dry deserts. Deserts on superhabitable planets would be more limited in area and would likely support habitat-rich coastal environments.

The optimum surface temperature for Earth-like life is unknown, although it appears that on Earth, organism diversity has been greater in warmer periods. It is therefore possible that exoplanets with slightly higher average temperatures than that of Earth are more suitable for life. The denser atmosphere of a superhabitable planet would naturally provide a greater average temperature and less variability of the global climate. Ideally, the temperature should reach the optimal levels for plant life, which is 25 °C (77 °F). In addition, a large distributed ocean would have the ability to regulate a planet's surface temperature similar to Earth's ocean currents, and could allow it to maintain a moderate temperature within the habitable zone.

There are no solid arguments to explain if Earth's atmosphere has the optimal composition, but relative atmospheric oxygen levels is required to meet the high-energy demands of complex life (O2). Therefore, it is hypothesized that oxygen abundance in the atmosphere is essential for complex life on other worlds.