| Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mission statement | "A shared blueprint for peace and prosperity for people and the planet, now and into the future" |

| Location | Global |

| Founder | United Nations |

| Established | 2015 |

| Disestablished | 2030 |

| Website | www |

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations (UN) members in 2015, created 17 world Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The aim of these global goals is "peace and prosperity for people and the planet" – while tackling climate change and working to preserve oceans and forests. The SDGs highlight the connections between the environmental, social and economic aspects of sustainable development. Sustainability is at the center of the SDGs, as the term sustainable development implies.

These goals are ambitious, and the reports and outcomes to date indicate a challenging path. Most, if not all, of the goals are unlikely to be met by 2030. Rising inequalities, climate change, and biodiversity loss are topics of concerns threatening progress. The COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 to 2023 made these challenges worse, and some regions, such as Asia, have experienced significant setbacks during that time.

There are cross-cutting issues and synergies between the different goals; for example, for SDG 13 on climate action, the IPCC sees robust synergies with SDGs 3 (health), 7 (clean energy), 11 (cities and communities), 12 (responsible consumption and production) and 14 (oceans). On the other hand, critics and observers have also identified trade-offs between the goals, such as between ending hunger and promoting environmental sustainability. Furthermore, concerns have arisen over the high number of goals (compared to the eight Millennium Development Goals), leading to compounded trade-offs, a weak emphasis on environmental sustainability, and difficulties tracking qualitative indicators.

The political impact of the SDGs has been rather limited, and the SDGs have struggled to achieve transformative changes in policy and institutional structures. Also, funding remains a critical issue for achieving the SDGs. Significant financial resources would be required worldwide. The role of private investment and a shift towards sustainable financing are also essential for realizing the SDGs. Examples of progress from some countries demonstrate that achieving sustainable development through concerted global action is possible. The global effort for the SDGs calls for prioritizing environmental sustainability, understanding the indivisible nature of the goals, and seeking synergies across sectors.

The short titles of the 17 SDGs are: No poverty (SDG 1), Zero hunger (SDG 2), Good health and well-being (SDG 3), Quality education (SDG 4), Gender equality (SDG 5), Clean water and sanitation (SDG 6), Affordable and clean energy (SDG 7), Decent work and economic growth (SDG 8), Industry, innovation and infrastructure (SDG 9), Reduced inequalities (SDG 10), Sustainable cities and communities (SDG 11), Responsible consumption and production (SDG 12), Climate action (SDG 13), Life below water (SDG 14), Life on land (SDG 15), Peace, justice, and strong institutions (SDG 16), and Partnerships for the goals (SDG 17).

Principles

The SDGs are universal, time-bound, and legally non-binding policy objectives agreed upon by governments. They come close to prescriptive international norms but are generally more specific, and they can be highly ambitious. The overarching UN program "2030 Agenda" presented the SDGs in 2015 as a "supremely ambitious and transformative vision" that should be accompanied by "bold and transformative steps" with "scale and ambition".

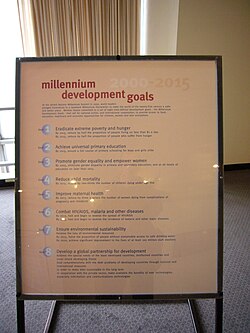

The SDGs apply to all countries of the world, not just developing countries like the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) did (from the year 2000 to 2015). They target all three dimensions of sustainability and sustainable development, namely the environmental, economic and social dimension. Another aspect that makes the SDGs different to the MDGs is that the development and negotiations of the SDGs were not "top down" by civil servants but were relatively open and transparent, aiming to include "bottom up" participation.

The SDGs are emphasizing inclusiveness in the national context and also in global governance. For the national context this means a focus on marginalised groups that are affected by exclusion and inequalities. For the global context, inclusiveness means a special emphasis on the least developed countries.

At the heart of the SDGs lies the pledge of the United Nations Member States to Leave No One Behind (abbreviated as LNOB). In other words: to reach the people and countries who are furthest behind first. The LNOB concept is a politically and technically challenging approach that is ambiguous and open to interpretation. A study from 2024 investigated 77 voluntary national reviews and found that people with disabilities are most often identified as furthest behind (>70%), followed by women and girls (>60%), youth (ca. 50%), elderly (45%), children (>40%), and refugees and migrants (ca. 30%).

Structure

Goals and targets

The lists of targets and indicators for each of the 17 SDGs was published in a UN resolution in July 2017. Each goal typically has eight to 12 targets, and each target has between one and four indicators used to measure progress toward reaching the targets, with the average of 1.5 indicators per target. The targets are either outcome targets (circumstances to be attained) or means of implementation targets. The latter targets were introduced late in the process of negotiating the SDGs to address the concern of some Member States about how the SDGs were to be achieved. Goal 17 is wholly about how the SDGs will be achieved.

The numbering system of targets is as follows: Outcome targets use numbers, whereas means of implementation targets use lower case letters. For example, SDG 6 has a total of 8 targets. The first six are outcome targets and are labeled Targets 6.1 to 6.6. The final two targets are means of implementation targets and are labeled as Targets 6.a and 6.b.

However, the connection between means of implementation with outcomes is not well proven. The means of implementation targets (those denoted with a letter, for example, Target 6.a) are not well conceptualized and not formulated in a consistent manner. Also, measuring and tracking their indicators is difficult.

Indicators and data

Indicators serve as the key tools for decision-makers to track progress towards the SDG targets. Therefore, they have a decisive impact on SDG implementation, as well as the ultimate determination of whether the world is closer to realizing the SDGs by 2030. National and local governments use the indicators to measure own progress towards sustainable development, which they report in their voluntary national and local reviews. The indicators are now widely deployed at all levels of sustainability governance. As of 2023, there are 231 official indicators in use.

Each target is typically measured with only 1.5 indicators, which monitor quantifiable changes in proportion, rate, amount, and the like. 62% of the targets are supported by sole indicators, effectively equating progress measured on the 105 indicators with progress on the 105 targets.

The implementation of the SDGs is underpinned by statistical data that should be accurate, timely, and reliable. This data, in turn, must be broken down by, for example, income, gender, age, disability, and geographic location. For example, the earlier Millennium Development Goal Number 1 aimed to “halve the proportion of people” suffering from hunger or extreme poverty. In contrast, the SDG Number 1 aims to “end poverty in all its forms everywhere”. This is also called the central principle of leaving no one behind.

The United Nations Statistics Division (UNSD) website provides a current official indicator list which includes all updates until the 51st session Statistical Commission in March 2020. The indicators for the targets have varying levels of methodological development and availability of data at the global level. Initially, some indicators (called Tier 3 indicators) had no internationally established methodology or standards. Later, the global indicator framework was adjusted so that Tier 3 indicators were either abandoned, replaced or refined.

The indicators were developed and annually reviewed by the Inter-agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators (IAEG-SDGs). The choice of indicators was delegated to statisticians who met behind closed doors after the goals and targets were established. However, scholars have pointed out that the selection of indicators was never free from politics. Statisticians received instructions from their governments, and the interests of powerful governments had a significant influence over the indicator selection process.

The indicator framework was comprehensively reviewed at the 51st session of the United Nations Statistical Commission in 2020. It will be reviewed again in 2025. At the 51st session of the Statistical Commission (held in New York City from 3 to 6 March 2020) a total of 36 changes to the global indicator framework were proposed for the commission's consideration. Some indicators were replaced, revised or deleted. Between 15 October 2018 and 17 April 2020, other changes were made to the indicators. Yet their measurement continues to be fraught with difficulties.

Custodian agencies

For each indicator, the Inter-Agency and Expert Group tried to designate at least one custodian agency and focal point that would be responsible for developing the methodology, data collection, data aggregation, and later reporting. The division of indicators was primarily based on existing mandates and organizational capacity. For example, the World Bank established itself as a data gatekeeper in this process through its broad mandate, staff, budget, and expertise in large-scale data collection. The bank became formally involved in about 20 percent of all 231 SDG indicators; it served as the custodian agency for 20 of them and was involved in the development and monitoring of another 22.

Details of 17 goals and targets

Goal 1: No Poverty

SDG 1 is to "end poverty in all its forms everywhere." Achieving SDG 1 would end extreme poverty globally by 2030. One of its indicators is the proportion of population living below the poverty line. The data gets analyzed by sex, age, employment status, and geographical location (urban/rural). One of the key indicators that measure poverty is the proportion of population living below the international and national poverty line. Measuring the proportion of the population covered by social protection systems and living in households with access to basic services is also an indication of the level of poverty.

Goal 2: Zero hunger

SDG 2 is to: "End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and promote sustainable agriculture." Indicators for this goal are for example the prevalence of diet, prevalence of severe food insecurity, and prevalence of stunting among children under five years of age.

Goal 3: Good health and well-being

SDG 3 is to: "Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages." Important indicators here are life expectancy as well as child and maternal mortality. Further indicators are for example deaths from road traffic injuries, prevalence of current tobacco use, and suicide mortality rate.

Goal 4: Quality education

SDG 4 is to: "Ensure inclusive and equitable quality education and promote lifelong learning opportunities for all." The indicators for this goal are, for example, attendance rates at primary schools, completion rates of primary school education, participation in tertiary education, and so forth. In each case, parity indices are looked at to ensure that disadvantaged students do not miss out (data is collected on "female/male, rural/urban, bottom/top wealth quintile and others such as disability status, indigenous peoples"). There is also an indicator around the facilities that the school buildings have (access to electricity, the internet, computers, drinking water, toilets etc.).

Goal 5: Gender equality

SDG 5 is to: "Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls." Indicators include, for example, having suitable legal frameworks and the representation by women in national parliament or in local deliberative bodies. Numbers on forced marriage and female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) are also included in another indicator.

Goal 6: Clean water and sanitation

SDG 6 is to: "Ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all." The Joint Monitoring Programme (JMP) of WHO and UNICEF is responsible for monitoring progress to achieve the first two targets of this goal. Important indicators for this goal are the percentages of the population that uses safely managed drinking water, and has access to safely managed sanitation. The JMP reported in 2017 that 4.5 billion people do not have safely managed sanitation. Another indicator looks at the proportion of domestic and industrial wastewater that is safely treated.

Goal 7: Affordable and clean energy

SDG 7 is to "Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern energy for all." One of the indicators for this goal is the percentage of population with access to electricity (progress in expanding access to electricity has been made in several countries, notably India, Bangladesh, and Kenya). Other indicators look at the renewable energy share and energy efficiency.

Goal 8: Decent work and economic growth

SDG 8 is to: "Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment and decent work for all." Important indicators for this goal include economic growth in least developed countries and the rate of real GDP per capita. Further examples are rates of youth unemployment and occupational injuries or the number of women engaged in the labor force compared to men.

Goal 9: Industry, Innovation, Technology and Infrastructure

SDG 9 is to: "Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable industrialization, and foster innovation." Indicators in this goal include for example, the proportion of people who are employed in manufacturing activities, are living in areas covered by a mobile network, or who have access to the internet. An indicator that is connected to climate change is "CO2 emissions per unit of value added."

Goal 10: Reduced inequality

SDG 10 is to: "Reduce inequality within and among countries." Important indicators for this SDG are: income disparities, aspects of gender and disability, as well as policies for migration and mobility of people.

Goal 11: Sustainable cities and communities

SDG 11 is to: "Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient, and sustainable."[37] Important indicators for this goal are the number of people living in urban slums, the proportion of the urban population who has convenient access to public transport, and the extent of built-up area per person.

Goal 12: Responsible consumption and production

SDG 12 is to: "Ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns." One of the indicators is the number of national policy instruments to promote sustainable consumption and production patterns. Another one is global fossil fuel subsidies. An increase in domestic recycling and a reduced reliance on the global plastic waste trade are other actions that might help meet the goal.

Goal 13: Climate action

SDG 13 is to: "Take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts by regulating emissions and promoting developments in renewable energy." In 2021 to early 2023, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) published its Sixth Assessment Report which assesses scientific, technical, and socio-economic information concerning climate change.

Goal 14: Life below water

SDG 14 is to: "Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development." The current efforts to protect oceans, marine environments and small-scale fishers are not meeting the need to protect the resources. Increased ocean temperatures and oxygen loss act concurrently with ocean acidification to constitute the deadly trio of climate change pressures on the marine environment.

Goal 15: Life on land

SDG 15 is to: "Protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss." The proportion of remaining forest area, desertification and species extinction risk are example indicators of this goal.

Goal 16: Peace, justice and strong institutions

SDG 16 is to: "Promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels." Rates of birth registration and prevalence of bribery are two examples of indicators included in this goal.

An inclusive society has "mechanisms to enable diversity and social justice, accommodate the special needs of vulnerable and disadvantaged groups, and facilitate democratic participation".

Goal 17: Partnerships for the goals

SDG 17 is to: "Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development." Increasing international cooperation is seen as vital to achieving each of the 16 previous goals. Developing multi-stakeholder partnerships to facilitate knowledge exchange, expertise, technology, and financial resources is recognized as critical to overall success of the SDGs. The goal includes improving north–south and South–South cooperation. Public-private partnerships which involve civil societies are specifically mentioned.

Public relations

The 2030 Agenda did not create specific authority for communicating the SDGs; however, both international and local advocacy organizations have pursued significant non-state resources to communicate the SDGS. UN agencies which are part of the United Nations Development Group decided to support an independent campaign to communicate the new SDGs to a wider audience. This campaign, Project Everyone, had the support of corporate institutions and other international organizations.

Using the text drafted by diplomats at the UN level, a team of communication specialists developed icons for every goal. They also shortened the title The 17 Sustainable Development Goals to Global Goals, then ran workshops and conferences to communicate the Global Goals to a global audience.

The Aarhus Convention is a United Nations convention passed in 2001, explicitly to encourage and promote effective public engagement in environmental decision making. Information transparency related to social media and the engagement of youth are two issues related to the Sustainable Development Goals that the convention has addressed.

Advocates

In 2019 and then in 2021, United Nations Secretary-General António Guterres appointed 17 SDG advocates. The role of the public figures is to raise awareness, inspire greater ambition, and push for faster action on the SDGs. The co-chairs are: Mia Mottley, Prime Minister of Barbados and Justin Trudeau, Prime Minister of Canada.

Global events

Global Goals Week is an annual week-long event in September for action, awareness, and accountability for the Sustainable Development Goals. It is a shared commitment for over 100 partners to ensure quick action on the SDGs by sharing ideas and transformative solutions to global problems. It first took place in 2016. It is often held concurrently with Climate Week NYC.

The Arctic Film Festival is an annual film festival organized by HF Productions and supported by the SDGs' Partnership Platform. Held for the first time in 2019, the festival is expected to take place every year in September in Longyearbyen, Svalbard, Norway.

History

The Post-2015 Development Agenda was a process from 2012 to 2015 led by the United Nations to define the future global development framework that would succeed the Millennium Development Goals which ended in 2015.

In 1983, the United Nations created the World Commission on Environment and Development (later known as the Brundtland Commission), which defined sustainable development as "meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs." In 1992, the first United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) or Earth Summit was held in Rio de Janeiro, where the first agenda for Environment and Development, also known as Agenda 21, was developed and adopted.

In 2012, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (UNCSD), also known as Rio+20, was held as a 20-year follow up to UNCED. Colombia proposed the idea of the SDGs at a preparation event for Rio+20 held in Indonesia in July 2011. In September 2011, this idea was picked up by the United Nations Department of Public Information 64th NGO Conference in Bonn, Germany. The outcome document proposed 17 sustainable development goals and associated targets. In the run-up to Rio+20 there was much discussion about the idea of the SDGs. At the Rio+20 Conference, a resolution known as "The Future We Want" was reached by member states. Among the key themes agreed on were poverty eradication, energy, water and sanitation, health, and human settlement.

In January 2013, the 30-member UN General Assembly Open Working Group (OWG) on Sustainable Development Goals was established to identify specific goals for the SDGs. The OWG submitted their proposal of 8 SDGs and 169 targets to the 68th session of the General Assembly in September 2014. On 5 December 2014, the UN General Assembly accepted the Secretary General's Synthesis Report, which stated that the agenda for the post-2015 SDG process would be based on the OWG proposals.

In 2015, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) created the SDGs as part of the Post-2015 Development Agenda. These goals were formally articulated and adopted in a UNGA resolution known as the 2030 Agenda. On 6 July 2017, the SDGs were made more actionable by a UNGA resolution that identifies specific targets for each goal and provides indicators to measure progress. Most targets are to be achieved by 2030, although some have no end date.

Adoption

On 25 September 2015, the 193 countries of the UN General Assembly adopted the 2030 Development Agenda titled "Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development." This agenda has 92 paragraphs. Paragraph 59 outlines the 17 Sustainable Development Goals and the associated 169 targets and 232 indicators.

The UN-led process involved its 193 member states and global civil society. The resolution is a broad intergovernmental agreement that acts as the Post-2015 Development Agenda. The SDGs build on the principles agreed upon in Resolution A/RES/66/288, entitled "The Future We Want". This was a non-binding document released as a result of Rio+20 Conference held in 2012.

Implementation

Implementation of the SDGs started worldwide in 2016. This process can also be called Localizing the SDGs. In 2019 António Guterres (secretary-general of the United Nations) issued a global call for a Decade of Action to deliver the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. This decade will last from 2020 to 2030. The plan is that the secretary general of the UN will convene an annual platform for driving the Decade of Action.

There are two main types of actors for implementation of the SDGs: state and non-state actors. The former include national governments and sub-national authorities, whereas the latter are corporations and civil society.

Cross-cutting issues

The widespread consensus is that progress on all of the SDGs will be stalled if women's empowerment and gender equality are not prioritized, and treated holistically. The SDGs look to policy makers as well as private sector executives and board members to work toward gender equality. Statements from diverse sources such as the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), UN Women and the World Pensions Forum, have noted that investments in women and girls have positive impacts on economies. National and global development investments in women and girls often exceed their initial scope.

Gender equality is mainstreamed throughout the SDG framework by ensuring that as much sex-disaggregated data as possible are collected.

Education for sustainable development (ESD) is explicitly recognized in the SDGs as part of Target 4.7 of the SDG on education. UNESCO promotes the Global Citizenship Education (GCED) as a complementary approach. Education for sustainable development is important for all the other 16 SDGs.

Culture is explicitly referenced in SDG 11 Target 4 ("Strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world's cultural and natural heritage"). However, culture is seen as a cross-cutting theme because it impacts several SDGs. For example, culture plays a role in SDG targets where they relate to environment and resilience (within SDGs 11, 12 and 16), prosperity and livelihoods (within SDG 8), inclusion and participation (within SDG 11 and 16).

SDGs 1 to 6 directly address health disparities, primarily in developing countries. These six goals address key issues in global public health, poverty, hunger and food security, health, education, gender equality and women's empowerment, as well as water and sanitation. Public health officials can use these goals to set their own agenda and plan for smaller scale initiatives for their organizations.

The links between the various sustainable development goals and public health are numerous and well established:

- SDG 1: Living below the poverty line is attributed to poorer health outcomes and can be even worse for persons living in developing countries where extreme poverty is more common. A child born into poverty is twice as likely to die before the age of five compared to a child from a wealthier family.

- SDG 2: The detrimental effects of hunger and malnutrition that can arise from systemic challenges with food security are enormous. The World Health Organization estimates that 12.9 percent of the population in developing countries is undernourished.

- SDG 4 and 5: Educational equity has yet to be reached in the world. Public health efforts are impeded by this, as a lack of education can lead to poorer health outcomes. This is shown by children of mothers who have no education having a lower survival rate compared to children born to mothers with primary or greater levels of education.

Synergies

Synergies amongst the SDGs are "the good antagonists of trade-offs." With regards to SDG 13 on climate action, the IPCC sees robust synergies particularly for the SDGs 3 (health), 7 (clean energy), 11 (cities and communities), 12 (responsible consumption and production) and 14 (oceans).

To meet SDG 13 and other SDGs, sustained long-term investment in green innovation is required to: decarbonize the physical capital stock – energy, industry, and transportation infrastructure – and ensure its resilience to a changing future climate; to preserve and enhance natural capital – forests, oceans, and wetlands; and to train people to work in a climate-neutral economy.

International organizations

Many international organizations have committed to the SDGs since 2015. Examples for international organizations include: UN General Assembly, World Trade Organization, African Development Bank, UN Economic and Social Council, UN Security Council, Asian Development Bank. However, some international organizations, such as the World Bank, often have "cherry-picked" goals and engaged in selective mainstreaming.

In general, the SDGs might be a low priority for international organizations that have many other assignments that are often more binding, have more urgent deliverables, and have more repercussions in case of inaction. The breadth of the SDGs, covering nearly all areas of global governance, is at odds with international organizations that over time have become highly functionally differentiated and that operate through intra-organizational compromises. Most international organizations primarily see the SDGs as separate goals rather than an integrated agenda, leading to the cherry-picking of those goals that best fit their agenda.

Funding

Cost estimates

The United Nations estimates that for Africa, considering the continent's population growth, yearly funding of $1.3 trillion would be needed to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals in Africa. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) also estimates that $50 billion may be needed only to cover the expenses of climate adaptation. The IMF has also taken the initiative to achieve the SDGs by offering their support to developing countries.

Estimates for providing clean water and sanitation for the whole population of all continents have been as high as US$200 billion. The World Bank says that estimates need to be made country by country, and reevaluated frequently over time.

In 2014, UNCTAD estimated the annual costs to achieving the UN Goals at US$2.5 trillion per year. Another estimate from 2018 (by the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics, that conducts the World Social Capital Monitor) found that to reach all of the SDGs this would require between US$2.5 and $5.0 trillion per year.

A cost estimate from 2020 stated that: "In developing countries, the [financial] gap is estimated to be US$ 2.5 trillion per year pre-COVID-19 pandemic, which was projected to have risen to US$ 4.2 trillion in 2020 alone." For example in Indonesia, the SDG financing gap (or costs to achieve the SDGs), was estimated in 2021 to be US$4.7 trillion. The same study explains that the SDGs are also an investable proposition. This means that the SDGs are also a business opportunity. The financial value of this opportunity amounts to "US$ 12 trillion per annum in four sectors alone – food, cities, energy and materials and health and well-being – with developing countries accounting for more than half the value of SDG business opportunities".

Sources of finance

There have been several processes and agendas at the United Nations level for financing the SDGs, for example the Addis Ababa Action Agenda on Financing for Development in 2015 (the Addis Ababa Action Agenda was the outcome of the 2015 Third International Conference on Financing for Development, held in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia) and the Secretary-General Strategy for Financing the 2030 Agenda in 2018. In 2017 the UN launched the Inter-agency Task Force on Financing for Development (UN IATF on FfD) that invited a public dialogue. Also, multilateral development banks initiated the agenda From Billions to Trillions: Transforming Development Finance in 2015.

The top-5 sources of financing for development were estimated in 2018 to be: Real new sovereign debt OECD countries, military expenditures, official increase sovereign debt OECD countries, remittances from expats to developing countries, official development assistance (ODA). Private finance or market-making processes are another option for development finance, for example green bonds and SDG bonds.

The Rockefeller Foundation asserted in 2017 that "The key to financing and achieving the SDGs lies in mobilizing a greater share of the $200+ trillion in annual private capital investment flows toward development efforts, and philanthropy has a critical role to play in catalyzing this shift." Large-scale funders participating in a Rockefeller Foundation-hosted design thinking workshop concluded that "while there is a moral imperative to achieve the SDGs, failure is inevitable if there aren't drastic changes to how we go about financing large scale change."

A meta-analysis published in 2022 found that there was scant evidence that governments have substantially reallocated funding to implement the SDGs, either for national implementation or for international cooperation. The SDGs do not seem to have changed public budgets and financial allocation mechanisms in any important way, except for some local governance contexts. National budgets cannot easily be reallocated.

SDG-driven investment

Capital stewardship is expected to play a crucial part in the progressive advancement of the SDG agenda to "shift the economic system towards sustainable investment by using the SDG framework across all asset classes." The notion of SDG Driven Investment gained further ground amongst institutional investors in 2019.

In 2017, 2018 and early 2019, the World Pensions Council (WPC) held a series of ESG-focused (Environmental, Social and Governance) discussions with pension board members (trustees) and senior investment executives from across G20 nations. Many pension investment executives and board members confirmed they were in the process of adopting or developing SDG-informed investment processes, with more ambitious investment governance requirements – notably when it comes to climate action, gender equality and social fairness.

Some studies, however, warn of selective implementation of SDGs and political risks linked to private investments in the context of continued shortage of public funding.

Results and outcomes

Most or all of the goals and targets are unlikely to be achieved by 2030. Countries are falling particularly short in efforts to reduce inequality (SDG 10), with inequality actually widening according to many indicators (as of 2023).

Of particular concern - which cut across many of the SDGs – are rising inequalities, ongoing climate change and increasing biodiversity loss. In addition, there is a trade-off between the planetary boundaries of Earth and the aspirations for wealth and well-being. This has been described as follows: "the world's social and natural biophysical systems cannot support the aspirations for universal human well-being embedded in the SDGs."

Due to various economic and social issues, many countries are seeing a major decline in the progress made. In Asia for example, data shows a loss of progress on goals 2, 8,10,11, and 15. Recommended approaches to still achieve the SDGs are: "Set priorities, focus on harnessing the environmental dimension of the SDGs, understand how the SDGs work as an indivisible system, and look for synergies."

Assessing the political impact of the SDGs

In 2022, a research project analyzed the political impacts of the SDGs as well as their "steering effects". The project was a "systematic meta-analysis of peer-reviewed academic literature". It reviewed over 3,000 scientific articles, mainly from the social sciences. These steering effects could be one of three types: discursive, normative or institutional effects. The presence of all three types of effects throughout a political system was defined as transformative impact, which is the eventual goal of the 2030 Agenda.

Discursive effects relate to changes in global and national debates that make them more aligned with the SDGs. Normative effects would be adjustments in legislative and regulatory frameworks and policies in line with, and because of, the SDGs. Institutional effects would be the creation of new departments, committees, offices or programs linked to the achievement of the SDGs or the realignment of existing institutions.

The review found that the SDGs have had only limited transformative political impact thus far. There have been some discursive impacts, like the broad uptake of the principle of leaving no one behind in pronouncements by policymakers and civil society activists. However, there is doubt that the SDGs can steer societies towards more ecological integrity at the planetary scale. This is because countries generally prioritize the socioeconomic SDGs (e.g. SDGs 8 to 12) over the environmentally oriented ones (e.g. SDGs 13 to 15), in alignment with their long-standing national development policies.

Impacts of COVID-19 pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic slowed progress towards achieving the SDGs. It was "the worst human and economic crisis in a lifetime." The pandemic threatened progress made in particular for SDG 3 (health), SDG 4 (education), SDG 6 (water and sanitation for all), SDG 10 (reduce inequality) and SDG 17 (partnerships).

At the UN High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development in July 2023, speakers remarked that the pandemic, and multiple worldwide crises such as climate change, threatened decades of progress on the SDGs.

Uneven priorities of goals

There is a risk of countries favoring (or cherry-picking) certain goals, thereby creating trade-offs and threatening policy coherence. As a result, some goals are "left behind" and hardly prioritized. For example, global and domestic inequality only barely made it into the final set of SDGs as SDG 10, and this goal is still poorly supported and often marginalized.

In 2020, researchers conducted a content analysis of the voluntary national reviews of 19 countries of varying income levels to find out which SDGs receive more attention than the others in national policies. They found that SDGs 1 and 8 (on poverty eradication and economic growth) are by far most widely prioritized. Some commentators argue that insufficient capacity of many countries to fully implement all SDGs makes prioritization inevitable or even necessary.

The practice of prioritizing certain SDGs by national governments is real and happening. Which SDGs are prioritized depends at least in part on the level of economic development of respective countries. The goals that are prioritized often correspond with what their existing priorities were before the SDGs came about. This implies the SDGs themselves do not directly steer national policies but rather the goals are used to legitimize existing priorities of national governments.

In 2019 five progress reports on the 17 SDGs were published. Three came from the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), one from the Bertelsmann Foundation and one from the European Union. A review of the five reports analyzed which of the 17 Goals were addressed in priority and which ones were left behind. In explanation of the findings, the Basel Institute of Commons and Economics said Biodiversity, Peace and Social Inclusion were "left behind" by quoting the official SDGs motto "Leaving no one behind."

| SDG topic | Rank | Average rank | Mentions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health | 1 | 3.2 | 1814 |

| Energy Climate Water |

2 | 4.0 | 1328 1328 1784 |

| Education | 3 | 4.6 | 1351 |

| Poverty | 4 | 6.2 | 1095 |

| Food | 5 | 7.6 | 693 |

| Economic Growth | 6 | 8.6 | 387 |

| Technology | 7 | 8.8 | 855 |

| Inequality | 8 | 9.2 | 296 |

| Gender Equality | 9 | 10.0 | 338 |

| Hunger | 10 | 10.6 | 670 |

| Justice | 11 | 10.8 | 328 |

| Governance | 12 | 11.6 | 232 |

| Decent Work | 13 | 12.2 | 277 |

| Peace | 14 | 12.4 | 282 |

| Clean Energy | 15 | 12.6 | 272 |

| Life on Land | 16 | 14.4 | 250 |

| Life below Water | 17 | 15.0 | 248 |

| Social Inclusion | 18 | 16.4 | 22 |

Monitoring progress

Voluntary national reviews

Countries can carry out voluntary national reviews (VNRs), thereby documenting their progress in achieving the SDGs and sharing their experiences with other interested parties. VNRs are loosely based on common guidelines that the UN published for VNRs which makes it relatively easy to compare them. For example, as part of these guidelines, countries are asked to include a separate chapter on Leave No One Behind in which they explain how the principle has been translated into concrete actions. Annual synthesis reports summarise the VNRs across a group of countries. For example, the ninth annual VNR Synthesis Report was published in 2024 and included notable experiences and trends from 36 countries.

Tools and websites

To facilitate monitoring of progress on SDG implementation, the online SDG Tracker was launched in June 2018 to present all available data across all indicators. It relies on the Our World in Data database and is also based at the University of Oxford. The publication has global coverage and tracks whether the world is making progress towards the SDGs. It aims to make the data on the 17 goals available and understandable to a wide audience. The SDG-Tracker highlights that the world is currently (early 2019) very far away from achieving the goals.

The Global SDG Index and Dashboards Report is the first publication to track countries' performance on all 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The annual publication, co-produced by Bertelsmann Stiftung and SDSN, includes a ranking and dashboards that show key challenges for each country in terms of implementing the SDGs. The publication also shows an analysis of government efforts to implement the SDGs.

UN High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF)

The SDGs are monitored by the United Nations' High-level Political Forum on Sustainable Development (HLPF), an annual forum held under the auspices of the United Nations Economic and Social Council. This subdivision should be a "regular meeting place for governments and non-state representatives to assess global progress towards sustainable development." High-level progress reports for all the SDGs are published in the form of reports by the United Nations Secretary General.

The HLPF has several problems due to a lack of political leadership and divergent national interests. It has not been able to promote system-wide coherence. Therefore, this reporting system is mainly just a platform for voluntary reporting and peer learning among governments.

Challenges

Too many goals and overall problems

Scholars have pointed out flaws in the design of the SDGs for the following aspects: "the number of goals, the structure of the goal framework (for example, the non-hierarchical structure), the coherence between the goals, the specificity or measurability of the targets, the language used in the text, and their reliance on neoliberal economic development-oriented sustainable development as their core orientation."

The SDGs may simply maintain the status quo and fall short of delivering an ambitious development agenda. The current status quo has been described as "separating human wellbeing and environmental sustainability, failing to change governance and to pay attention to trade-offs, root causes of poverty and environmental degradation, and social justice issues."

A commentary in The Economist in 2015 argued that 169 targets for the SDGs is too many, describing them as sprawling, misconceived and a mess compared to the eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

Problems with indicators

A concern has been raised over the large number of indicators and the associated cost of SDG monitoring, which is estimated to be in the billions of dollars. Investments in building statistical capacity in developing countries through training, resources, and support is needed. This burden, coupled with the fact that many indicators have been found to be inadequate measures of progress, has sparked debate among scholars. Some have called for reducing the number of indicators whereas others say more, and more diverse, indicators are needed.

Some indicators are controversial such as those based on gross domestic product (GDP). For example, GDP forms the basis of 17 indicators used to measure progress towards 9 goals and 15 targets, when most of these goals and targets do not include GDP in their wording. Scholars have suggested developing alternative indicators by creating of a new measure that could complement and eventually replace GDP. The SDG framework, specifically Target 17.19 of SDG 17, already provides a basis for organizing such an effort. This target highlights the need to move beyond indicators such as GDP and to embrace well-being, happiness, or life satisfaction as key measures.

Weak on environmental sustainability

Scholars have criticized that the SDGs "fail to recognize that planetary, people and prosperity concerns are all part of one earth system, and that the protection of planetary integrity should not be a means to an end, but an end in itself." The SDGs "remain fixated on the idea that economic growth is foundational to achieve all pillars of sustainable development." They do not prioritize environmental protection. In regions still dependent on fossil fuels, the rapid growth and profitability of AI infrastructure is creating economic incentives to invest in clean energy. However, AI-driven expansion has also led to higher emissions, revealing a tension between economic growth and sustainable goals.

The SDGs include three environment-focused SDGs, which are Goal 13, 14 and 15 (climate, land and oceans), but there is no overarching environmental or planetary goal. The SDGs do not pursue planetary integrity as such.

Environmental constraints and planetary boundaries are underrepresented within the SDGs. For instance, the way the current SDGs are structured leads to a negative correlation between environmental sustainability and SDGs, with most indicators within even the sustainability-focused goals focusing on social or economic outcomes. They could unintentionally promote environmental destruction in the name of sustainable development.

Certain studies also argue that the focus of the SDGs on neoliberal sustainable development is detrimental to planetary integrity and justice. Both of these ambitions (planetary integrity and justice) would require limits to economic growth.

Scientists have proposed several ways to address the weaknesses regarding environmental sustainability in the SDGs:

- The monitoring of essential variables to better capture the essence of coupled environmental and social systems that underpin sustainable development, helping to guide coordination and systems transformation.

- More attention to the context of the biophysical systems in different places (e.g., coastal river deltas, mountain areas)

- Better understanding of feedbacks across scales in space (e.g., through globalization) and time (e.g., affecting future generations) that could ultimately determine the success or failure of the SDGs.

Ethical aspects

There are concerns about the ethical orientation of the SDGs: they remain "underpinned by strong (Western) modernist notions of development: sovereignty of humans over their environment (anthropocentricism), individualism, competition, freedom (rights rather than duties), self-interest, belief in the market leading to collective welfare, private property (protected by legal systems), rewards based on merit, materialism, quantification of value, and instrumentalization of labor.".

A meta-analysis review study in 2022 found that: "There is even emerging evidence that the SDGs might have even adverse effects, by providing a "smokescreen of hectic political activity" that blurs a reality of stagnation, dead ends and business-as-usual."

Trade-offs and priorities

The trade-offs among the 17 SDGs might prevent their realization. For example, these are three difficult trade-offs to consider: "How can ending hunger be reconciled with environmental sustainability? (SDG targets 2.3 and 15.2) How can economic growth be reconciled with environmental sustainability? (SDG targets 9.2 and 9.4) How can income inequality be reconciled with economic growth? (SDG targets 10.1 and 8.1)."

The SDGs do not specifically address the tensions between economic growth and environmental sustainability. Instead, they emphasize "longstanding but dubious claims about decoupling and resource efficiency as technological solutions to the environmental crisis." For example, continued global economic growth of 3 percent (SDG 8) may not be reconcilable with ecological sustainability goals, because the required rate of absolute global eco-economic decoupling is far higher than any country has achieved in the past.

The SDGs are also said to be internally incoherent, with some inherently conflictive targets.

Examples of progress

A study in 2024 predicted SDG scores of regions until 2030 using machine learning models. The forecast results for 2030 show that "OECD countries" (80) (with a 2.8% change) and "Eastern Europe and Central Asia" (74) (with a 2.37% change) are expected to achieve the highest SDG scores. "Latin America and the Caribbean" (73) (with a 4.17% change), "East and South Asia" (69) (with a 2.64% change), "Middle East and North Africa" (68) (with a 2.32% change), and "Sub-Saharan Africa" (56) (with a 7.2% change) will display lower levels of SDG achievement, respectively.

Asia and Pacific

Australia

The Commonwealth of Australia was one of the 193 countries that adopted the 2030 Agenda in September 2015. Implementation of the agenda is led by the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) and the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (PM&C) with different federal government agencies responsible for each of the goals.

In November 2020, the Transforming Australia: SDG Progress Report stated that while Australia was performing well in health (SDG 3) and education (SDG 4) it was falling behind in the reduction of CO2 emissions (SDG 13), waste and environmental degradation (SDG 12, SDG 14 and SDG 15), and addressing economic inequality (SDG 10).China

UN Secretary General Guterres has praised China's Belt and Road Initiative for its capacity to advance the sustainable development goals. Institutional connections between the BRI and multiple UN bodies have also been established.

Africa

The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) has collected information to show how awareness about the SDGs among government officers, civil society and others has been created in many African countries.

Nigeria

Europe and the Middle East

Baltic nations, via the Council of the Baltic Sea States, have created the Baltic 2030 Action Plan.

Lebanon

Syria

Higher education in Syria began with sustainable development steps through Damascus University.