| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nanobiotechnology |

Nanobiotechnology, bionanotechnology, and nanobiology are terms that refer to the intersection of nanotechnology and biology. Given that the subject is one that has only emerged very recently, bionanotechnology and nanobiotechnology serve as blanket terms for various related technologies.

This discipline helps to indicate the merger of biological research with various fields of nanotechnology. Concepts that are enhanced through nanobiology include: nanodevices (such as biological machines), nanoparticles, and nanoscale phenomena that occurs within the discipline of nanotechnology. This technical approach to biology allows scientists to imagine and create systems that can be used for biological research. Biologically inspired nanotechnology uses biological systems as the inspirations for technologies not yet created. However, as with nanotechnology and biotechnology, bionanotechnology does have many potential ethical issues associated with it.

The most important objectives that are frequently found in nanobiology involve applying nanotools to relevant medical/biological problems and refining these applications. Developing new tools, such as peptoid nanosheets, for medical and biological purposes is another primary objective in nanotechnology. New nanotools are often made by refining the applications of the nanotools that are already being used. The imaging of native biomolecules, biological membranes, and tissues is also a major topic for nanobiology researchers. Other topics concerning nanobiology include the use of cantilever array sensors and the application of nanophotonics for manipulating molecular processes in living cells.

Recently, the use of microorganisms to synthesize functional nanoparticles has been of great interest. Microorganisms can change the oxidation state of metals. These microbial processes have opened up new opportunities for us to explore novel applications, for example, the biosynthesis of metal nanomaterials. In contrast to chemical and physical methods, microbial processes for synthesizing nanomaterials can be achieved in aqueous phase under gentle and environmentally benign conditions. This approach has become an attractive focus in current green bionanotechnology research towards sustainable development.

Terminology

The terms are often used interchangeably. When a distinction is intended, though, it is based on whether the focus is on applying biological ideas or on studying biology with nanotechnology. Bionanotechnology generally refers to the study of how the goals of nanotechnology can be guided by studying how biological "machines" work and adapting these biological motifs into improving existing nanotechnologies or creating new ones. Nanobiotechnology, on the other hand, refers to the ways that nanotechnology is used to create devices to study biological systems.

In other words, nanobiotechnology is essentially miniaturized biotechnology, whereas bionanotechnology is a specific application of nanotechnology. For example, DNA nanotechnology or cellular engineering would be classified as bionanotechnology because they involve working with biomolecules on the nanoscale. Conversely, many new medical technologies involving nanoparticles as delivery systems or as sensors would be examples of nanobiotechnology since they involve using nanotechnology to advance the goals of biology.

The definitions enumerated above will be utilized whenever a distinction between nanobio and bionano is made in this article. However, given the overlapping usage of the terms in modern parlance, individual technologies may need to be evaluated to determine which term is more fitting. As such, they are best discussed in parallel.

Concepts

Most of the scientific concepts in bionanotechnology are derived from other fields. Biochemical principles that are used to understand the material properties of biological systems are central in bionanotechnology because those same principles are to be used to create new technologies. Material properties and applications studied in bionanoscience include mechanical properties (e.g. deformation, adhesion, failure), electrical/electronic (e.g. electromechanical stimulation, capacitors, energy storage/batteries), optical (e.g. absorption, luminescence, photochemistry), thermal (e.g. thermomutability, thermal management), biological (e.g. how cells interact with nanomaterials, molecular flaws/defects, biosensing, biological mechanisms such as mechanosensation), nanoscience of disease (e.g. genetic disease, cancer, organ/tissue failure), as well as biological computing (e.g. DNA computing) and agriculture (target delivery of pesticides, hormones and fertilizers. The impact of bionanoscience, achieved through structural and mechanistic analyses of biological processes at nanoscale, is their translation into synthetic and technological applications through nanotechnology.

Nanobiotechnology takes most of its fundamentals from nanotechnology. Most of the devices designed for nano-biotechnological use are directly based on other existing nanotechnologies. Nanobiotechnology is often used to describe the overlapping multidisciplinary activities associated with biosensors, particularly where photonics, chemistry, biology, biophysics, nanomedicine, and engineering converge. Measurement in biology using wave guide techniques, such as dual-polarization interferometry, is another example.

Applications

Applications of bionanotechnology are extremely widespread. Insofar as the distinction holds, nanobiotechnology is much more commonplace in that it simply provides more tools for the study of biology. Bionanotechnology, on the other hand, promises to recreate biological mechanisms and pathways in a form that is useful in other ways.

Nanomedicine

Nanomedicine is a field of medical science whose applications are increasing.

- Nanobots

The field includes nanorobots and biological machines, which constitute a very useful tool to develop this area of knowledge. In the past years, researchers have made many improvements in the different devices and systems required to develop functional nanorobots – such as motion and magnetic guidance. This supposes a new way of treating and dealing with diseases such as cancer; thanks to nanorobots, side effects of chemotherapy could get controlled, reduced and even eliminated, so some years from now, cancer patients could be offered an alternative to treat such diseases instead of chemotherapy, which causes secondary effects such as hair loss, fatigue or nausea killing not only cancerous cells but also the healthy ones. Nanobots could be used for various therapies, surgery, diagnosis, and medical imaging – such as via targeted drug-delivery to the brain (similar to nanoparticles) and other sites. Programmability for combinations of features such as "tissue penetration, site-targeting, stimuli responsiveness, and cargo-loading" makes such nanobots promising candidates for "precision medicine".

At a clinical level, cancer treatment with nanomedicine would consist of the supply of nanorobots to the patient through an injection that will search for cancerous cells while leaving the healthy ones untouched. Patients that are treated through nanomedicine would thereby not notice the presence of these nanomachines inside them; the only thing that would be noticeable is the progressive improvement of their health. Nanobiotechnology may be useful for medicine formulation.

"Precision antibiotics" has been proposed to make use of bacteriocin-mechanisms for targeted antibiotics.

- Nanoparticles

Nanoparticles are already widely used in medicine. Its applications overlap with those of nanobots and in some cases it may be difficult to distinguish between them. They can be used to for diagnosis and targeted drug delivery, encapsulating medicine. Some can be manipulated using magnetic fields and, for example, experimentally, remote-controlled hormone release has been achieved this way.

One example advanced application under development are "Trojan horse" designer-nanoparticles that makes blood cells eat away – from the inside out – portions of atherosclerotic plaque that cause heart attacks and are the current most common cause of death globally.

- Artificial cells

Artificial cells such as synthetic red blood cells that have all or many of the natural cells' known broad natural properties and abilities could be used to load functional cargos such as hemoglobin, drugs, magnetic nanoparticles, and ATP biosensors which may enable additional non-native functionalities.

- Other

Nanofibers that mimic the matrix around cells and contain molecules that were engineered to wiggle was shown to be a potential therapy for spinal cord injury in mice.

Technically, gene therapy can also be considered to be a form of nanobiotechnology or to move towards it. An example of an area of genome editing related developments that is more clearly nanobiotechnology than more conventional gene therapies, is synthetic fabrication of functional materials in tissues. Researcher made C. elegans worms synthesize, fabricate, and assemble bioelectronic materials in its brain cells. They enabled modulation of membrane properties in specific neuron populations and manipulation of behavior in the living animals which might be useful in the study and treatments for diseases such as multiple sclerosis in specific and demonstrates the viability of such synthetic in vivo fabrication. Moreover, such genetically modified neurons may enable connecting external components – such as prosthetic limbs – to nerves.

Nanosensors based on e.g. nanotubes, nanowires, cantilevers, or atomic force microscopy could be applied to diagnostic devices/sensors

Nanobiotechnology

Nanobiotechnology (sometimes referred to as nanobiology) in medicine may be best described as helping modern medicine progress from treating symptoms to generating cures and regenerating biological tissues.

Three American patients have received whole cultured bladders with the help of doctors who use nanobiology techniques in their practice. Also, it has been demonstrated in animal studies that a uterus can be grown outside the body and then placed in the body in order to produce a baby. Stem cell treatments have been used to fix diseases that are found in the human heart and are in clinical trials in the United States. There is also funding for research into allowing people to have new limbs without having to resort to prosthesis. Artificial proteins might also become available to manufacture without the need for harsh chemicals and expensive machines. It has even been surmised that by the year 2055, computers may be made out of biochemicals and organic salts.

In vivo biosensors

Another example of current nanobiotechnological research involves nanospheres coated with fluorescent polymers. Researchers are seeking to design polymers whose fluorescence is quenched when they encounter specific molecules. Different polymers would detect different metabolites. The polymer-coated spheres could become part of new biological assays, and the technology might someday lead to particles which could be introduced into the human body to track down metabolites associated with tumors and other health problems. Another example, from a different perspective, would be evaluation and therapy at the nanoscopic level, i.e. the treatment of nanobacteria (25-200 nm sized) as is done by NanoBiotech Pharma.

In vitro biosensors

"Nanoantennas" made out of DNA – a novel type of nano-scale optical antenna – can be attached to proteins and produce a signal via fluorescence when these perform their biological functions, in particular for their distinct conformational changes. This could be used for further nanobiotechnology such as various types of nanomachines, to develop new drugs, for bioresearch and for new avenues in biochemistry.

Energy

It may also be useful in sustainable energy: in 2022, researchers reported 3D-printed nano-"skyscraper" electrodes – albeit micro-scale, the pillars had nano-features of porosity due to printed metal nanoparticle inks – (nanotechnology) that house cyanobacteria for extracting substantially more sustainable bioenergy from their photosynthesis (biotechnology) than in earlier studies.

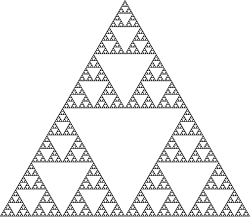

Nanobiology

While nanobiology is in its infancy, there are a lot of promising methods that may rely on nanobiology in the future. Biological systems are inherently nano in scale; nanoscience must merge with biology in order to deliver biomacromolecules and molecular machines that are similar to nature. Controlling and mimicking the devices and processes that are constructed from molecules is a tremendous challenge to face for the converging disciplines of nanobiotechnology. All living things, including humans, can be considered to be nanofoundries. Natural evolution has optimized the "natural" form of nanobiology over millions of years. In the 21st century, humans have developed the technology to artificially tap into nanobiology. This process is best described as "organic merging with synthetic". Colonies of live neurons can live together on a biochip device; according to research from Gunther Gross at the University of North Texas. Self-assembling nanotubes have the ability to be used as a structural system. They would be composed together with rhodopsins; which would facilitate the optical computing process and help with the storage of biological materials. DNA (as the software for all living things) can be used as a structural proteomic system – a logical component for molecular computing. Ned Seeman – a researcher at New York University – along with other researchers are currently researching concepts that are similar to each other.

Bionanotechnology

Distinction from nanobiotechnology

Broadly, bionanotechnology can be distinguished from nanobiotechnology in that it refers to nanotechnology that makes use of biological materials/components – it could in principle or does alternatively use abiotic components. It plays a smaller role in medicine (which is concerned with biological organisms). It makes use of natural or biomimetic systems or elements for unique nanoscale structures and various applications that may not be directionally associated with biology rather than mostly biological applications. In contrast, nanobiotechnology uses biotechnology miniaturized to nanometer size or incorporates nanomolecules into biological systems. In some future applications, both fields could be merged.

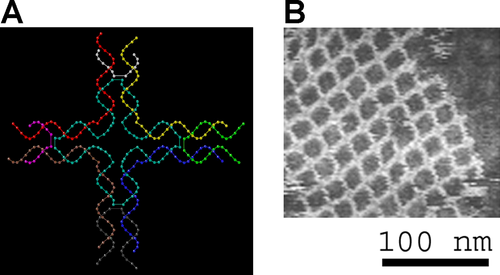

DNA

DNA nanotechnology is one important example of bionanotechnology. The utilization of the inherent properties of nucleic acids like DNA to create useful materials or devices – such as biosensors – is a promising area of modern research.

DNA digital data storage refers mostly to the use of synthesized but otherwise conventional strands of DNA to store digital data, which could be useful for e.g. high-density long-term data storage that isn't accessed and written to frequently as an alternative to 5D optical data storage or for use in combination with other nanobiotechnology.

Membrane materials

Another important area of research involves taking advantage of membrane properties to generate synthetic membranes. Proteins that self-assemble to generate functional materials could be used as a novel approach for the large-scale production of programmable nanomaterials. One example is the development of amyloids found in bacterial biofilms as engineered nanomaterials that can be programmed genetically to have different properties.

Lipid nanotechnology

Lipid nanotechnology is another major area of research in bionanotechnology, where physico-chemical properties of lipids such as their antifouling and self-assembly is exploited to build nanodevices with applications in medicine and engineering. Lipid nanotechnology approaches can also be used to develop next-generation emulsion methods to maximize both absorption of fat-soluble nutrients and the ability to incorporate them into popular beverages.

Computing

"Memristors" fabricated from protein nanowires of the bacterium Geobacter sulfurreducens which function at substantially lower voltages than previously described ones may allow the construction of artificial neurons which function at voltages of biological action potentials. The nanowires have a range of advantages over silicon nanowires and the memristors may be used to directly process biosensing signals, for neuromorphic computing (see also: wetware computer) and/or direct communication with biological neurons.

Other

Protein folding studies provide a third important avenue of research, but one that has been largely inhibited by our inability to predict protein folding with a sufficiently high degree of accuracy. Given the myriad uses that biological systems have for proteins, though, research into understanding protein folding is of high importance and could prove fruitful for bionanotechnology in the future.

Agriculture

In the agriculture industry, engineered nanoparticles have been serving as nano carriers, containing herbicides, chemicals, or genes, which target particular plant parts to release their content.

Previously nanocapsules containing herbicides have been reported to effectively penetrate through cuticles and tissues, allowing the slow and constant release of the active substances. Likewise, other literature describes that nano-encapsulated slow release of fertilizers has also become a trend to save fertilizer consumption and to minimize environmental pollution through precision farming. These are only a few examples from numerous research works which might open up exciting opportunities for nanobiotechnology application in agriculture. Also, application of this kind of engineered nanoparticles to plants should be considered the level of amicability before it is employed in agriculture practices. Based on a thorough literature survey, it was understood that there is only limited authentic information available to explain the biological consequence of engineered nanoparticles on treated plants. Certain reports underline the phytotoxicity of various origin of engineered nanoparticles to the plant caused by the subject of concentrations and sizes . At the same time, however, an equal number of studies were reported with a positive outcome of nanoparticles, which facilitate growth promoting nature to treat plant. In particular, compared to other nanoparticles, silver and gold nanoparticles based applications elicited beneficial results on various plant species with less and/or no toxicity. Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) treated leaves of Asparagus showed the increased content of ascorbate and chlorophyll. Similarly, AgNPs-treated common bean and corn has increased shoot and root length, leaf surface area, chlorophyll, carbohydrate and protein contents reported earlier. The gold nanoparticle has been used to induce growth and seed yield in Brassica juncea.

Nanobiotechnology is used in tissue cultures. The administration of micronutrients at the level of individual atoms and molecules allows for the stimulation of various stages of development, initiation of cell division, and differentiation in the production of plant material, which must be qualitatively uniform and genetically homogeneous. The use of nanoparticles of zinc (ZnO NPs) and silver (Ag NPs) compounds gives very good results in the micropropagation of chrysanthemums using the method of single-node shoot fragments.

Tools

This field relies on a variety of research methods, including experimental tools (e.g. imaging, characterization via AFM/optical tweezers etc.), x-ray diffraction based tools, synthesis via self-assembly, characterization of self-assembly (using e.g. MP-SPR, DPI, recombinant DNA methods, etc.), theory (e.g. statistical mechanics, nanomechanics, etc.), as well as computational approaches (bottom-up multi-scale simulation, supercomputing).

Risk management

As of 2009, the risks of nanobiotechnologies are poorly understood and in the U.S. there is no solid national consensus on what kind of regulatory policy principles should be followed. For example, nanobiotechnologies may have hard to control effects on the environment or ecosystems and human health. The metal-based nanoparticles used for biomedical prospectives are extremely enticing in various applications due to their distinctive physicochemical characteristics, allowing them to influence cellular processes at the biological level. The fact that metal-based nanoparticles have high surface-to-volume ratios makes them reactive or catalytic. Due to their small size, they are more likely to be able to penetrate biological barriers such as cell membranes and cause cellular dysfunction in living organisms. Indeed, the high toxicity of some transition metals can make it challenging to use mixed oxide NPs in biomedical uses. It triggers adverse effects on organisms, causing oxidative stress, stimulating the formation of ROS, mitochondrial perturbation, and the modulation of cellular functions, with fatal results in some cases.

Bonin notes that "Nanotechnology is not a specific determinate homogenous entity, but a collection of diverse capabilities and applications" and that nanobiotechnology research and development is – as one of many fields – affected by dual-use problems.