From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jupiter as seen by New Horizons spacecraft during its gravity assist in 2007

|

|||||||||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | |||||||||||||||

| Adjectives | Jovian | ||||||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[5][a] | |||||||||||||||

| Epoch J2000 | |||||||||||||||

| Aphelion | 5.458104 AU (816520800 km) | ||||||||||||||

| Perihelion | 4.950429 AU (740573600 km) | ||||||||||||||

| 5.204267 AU (778547200 km) | |||||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.048775 | ||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| 398.88 d[3] | |||||||||||||||

Average orbital speed

|

13.07 km/s[3] | ||||||||||||||

| 18.818° | |||||||||||||||

| Inclination |

|

||||||||||||||

| 100.492° | |||||||||||||||

| 275.066° | |||||||||||||||

| Known satellites | 67 (as of 2014[update]) | ||||||||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||||||||

Mean radius

|

69911±6 km[6][b] | ||||||||||||||

Equatorial radius

|

|||||||||||||||

Polar radius

|

|||||||||||||||

| Flattening | 0.06487±0.00015 | ||||||||||||||

| Volume | |||||||||||||||

| Mass | |||||||||||||||

Mean density

|

1.326 g/cm3[3][b] | ||||||||||||||

| 24.79 m/s2[3][b] 2.528 g |

|||||||||||||||

| 59.5 km/s[3][b] | |||||||||||||||

Sidereal rotation period

|

9.925 h[9] (9 h 55 m 30 s) | ||||||||||||||

Equatorial rotation velocity

|

12.6 km/s 45300 km/h |

||||||||||||||

| 3.13°[3] | |||||||||||||||

North pole right ascension

|

268.057° 17h 52m 14s[6] |

||||||||||||||

North pole declination

|

64.496°[6] | ||||||||||||||

| Albedo | 0.343 (Bond) 0.52 (geom.)[3] |

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||

| −1.6 to −2.94[3] | |||||||||||||||

| 29.8″ to 50.1″[3] | |||||||||||||||

| Atmosphere[3] | |||||||||||||||

Surface pressure

|

20–200 kPa[10] (cloud layer) | ||||||||||||||

| 27 km | |||||||||||||||

| Composition by volume | by volume:

|

||||||||||||||

Jupiter is primarily composed of hydrogen with a quarter of its mass being helium, although helium only comprises about a tenth of the number of molecules. It may also have a rocky core of heavier elements,[14] but like the other giant planets, Jupiter lacks a well-defined solid surface. Because of its rapid rotation, the planet's shape is that of an oblate spheroid (it possesses a slight but noticeable bulge around the equator). The outer atmosphere is visibly segregated into several bands at different latitudes, resulting in turbulence and storms along their interacting boundaries. A prominent result is the Great Red Spot, a giant storm that is known to have existed since at least the 17th century when it was first seen by telescope. Surrounding Jupiter is a faint planetary ring system and a powerful magnetosphere. Jupiter has at least 67 moons, including the four large Galilean moons discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Ganymede, the largest of these, has a diameter greater than that of the planet Mercury.

Jupiter has been explored on several occasions by robotic spacecraft, most notably during the early Pioneer and Voyager flyby missions and later by the Galileo orbiter. The most recent probe to visit Jupiter was the Pluto-bound New Horizons spacecraft in late February 2007. The probe used the gravity from Jupiter to increase its speed. Future targets for exploration in the Jovian system include the possible ice-covered liquid ocean on the moon Europa.

Structure

Jupiter is composed primarily of gaseous and liquid matter. It is the largest of the four giant planets in the Solar System and hence its largest planet. It has a diameter of 142,984 km (88,846 mi) at its equator. The density of Jupiter, 1.326 g/cm3, is the second highest of the giant planets, but lower than those of any of the four terrestrial planets.Composition

Jupiter's upper atmosphere is composed of about 88–92% hydrogen and 8–12% helium by percent volume of gas molecules. Because a helium atom has about four times as much mass as a hydrogen atom, the composition changes when described as the proportion of mass contributed by different atoms. Thus, the atmosphere is approximately 75% hydrogen and 24% helium by mass, with the remaining one percent of the mass consisting of other elements. The interior contains denser materials, such that the distribution is roughly 71% hydrogen, 24% helium and 5% other elements by mass. The atmosphere contains trace amounts of methane, water vapor, ammonia, and silicon-based compounds. There are also traces of carbon, ethane, hydrogen sulfide, neon, oxygen, phosphine, and sulfur. The outermost layer of the atmosphere contains crystals of frozen ammonia.[15][16] Through infrared and ultraviolet measurements, trace amounts of benzene and other hydrocarbons have also been found.[17]The atmospheric proportions of hydrogen and helium are close to the theoretical composition of the primordial solar nebula. Neon in the upper atmosphere only consists of 20 parts per million by mass, which is about a tenth as abundant as in the Sun.[18] Helium is also depleted, to about 80% of the Sun's helium composition. This depletion is a result of precipitation of these elements into the interior of the planet.[19] Abundances of heavier inert gases in Jupiter's atmosphere are about two to three times that of the Sun.

Based on spectroscopy, Saturn is thought to be similar in composition to Jupiter, but the other giant planets Uranus and Neptune have relatively much less hydrogen and helium.[20] Because of the lack of atmospheric entry probes, high-quality abundance numbers of the heavier elements are lacking for the outer planets beyond Jupiter.

Mass and size

Jupiter's diameter is one order of magnitude smaller (×0.10045) than the Sun, and one order of magnitude larger (×10.9733) than the Earth. The Great Red Spot has roughly the same size as the circumference of the Earth.

Jupiter's mass is 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined—this is so massive that its barycenter with the Sun lies above the Sun's surface at 1.068 solar radii from the Sun's center. Although this planet dwarfs the Earth with a diameter 11 times as great, it is considerably less dense. Jupiter's volume is that of about 1,321 Earths, but it is only 318 times as massive.[3][21] Jupiter's radius is about 1/10 the radius of the Sun,[22] and its mass is 0.001 times the mass of the Sun, so the density of the two bodies is similar.[23] A "Jupiter mass" (MJ or MJup) is often used as a unit to describe masses of other objects, particularly extrasolar planets and brown dwarfs. So, for example, the extrasolar planet HD 209458 b has a mass of 0.69 MJ, while Kappa Andromedae b has a mass of 12.8 MJ.[24]

Theoretical models indicate that if Jupiter had much more mass than it does at present, it would shrink.[25] For small changes in mass, the radius would not change appreciably, and above about 500 M⊕ (1.6 Jupiter masses)[25] the interior would become so much more compressed under the increased pressure that its volume would decrease despite the increasing amount of matter. As a result, Jupiter is thought to have about as large a diameter as a planet of its composition and evolutionary history can achieve.[26] The process of further shrinkage with increasing mass would continue until appreciable stellar ignition is achieved as in high-mass brown dwarfs having around 50 Jupiter masses.[27]

Although Jupiter would need to be about 75 times as massive to fuse hydrogen and become a star, the smallest red dwarf is only about 30 percent larger in radius than Jupiter.[28][29] Despite this, Jupiter still radiates more heat than it receives from the Sun; the amount of heat produced inside it is similar to the total solar radiation it receives.[30] This additional heat is generated by the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism through contraction. This process causes Jupiter to shrink by about 2 cm each year.[31]

When it was first formed, Jupiter was much hotter and was about twice its current diameter.[32]

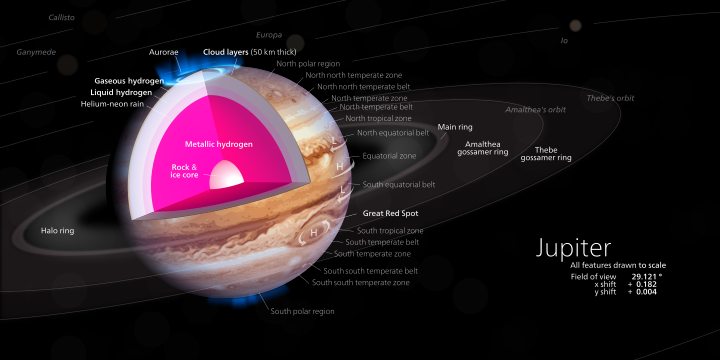

Internal structure

Jupiter is thought to consist of a dense core with a mixture of elements, a surrounding layer of liquid metallic hydrogen with some helium, and an outer layer predominantly of molecular hydrogen.[31]Beyond this basic outline, there is still considerable uncertainty. The core is often described as rocky, but its detailed composition is unknown, as are the properties of materials at the temperatures and pressures of those depths (see below). In 1997, the existence of the core was suggested by gravitational measurements,[31] indicating a mass of from 12 to 45 times the Earth's mass or roughly 4%–14% of the total mass of Jupiter.[30][33] The presence of a core during at least part of Jupiter's history is suggested by models of planetary formation that require the formation of a rocky or icy core massive enough to collect its bulk of hydrogen and helium from the protosolar nebula. Assuming it did exist, it may have shrunk as convection currents of hot liquid metallic hydrogen mixed with the molten core and carried its contents to higher levels in the planetary interior. A core may now be entirely absent, as gravitational measurements are not yet precise enough to rule that possibility out entirely.[31][34]

The uncertainty of the models is tied to the error margin in hitherto measured parameters: one of the rotational coefficients (J6) used to describe the planet's gravitational moment, Jupiter's equatorial radius, and its temperature at 1 bar pressure. The Juno mission, which launched in August 2011, is expected to better constrain the values of these parameters, and thereby make progress on the problem of the core.[35]

The core region is surrounded by dense metallic hydrogen, which extends outward to about 78% of the radius of the planet.[30] Rain-like droplets of helium and neon precipitate downward through this layer, depleting the abundance of these elements in the upper atmosphere.[19][36]

Above the layer of metallic hydrogen lies a transparent interior atmosphere of hydrogen. At this depth, the temperature is above the critical temperature, which for hydrogen is only 33 K[37] (see hydrogen). In this state, there are no distinct liquid and gas phases—hydrogen is said to be in a supercritical fluid state. It is convenient to treat hydrogen as gas in the upper layer extending downward from the cloud layer to a depth of about 1,000 km,[30] and as liquid in deeper layers. Physically, there is no clear boundary—the gas smoothly becomes hotter and denser as one descends.[38][39]

The temperature and pressure inside Jupiter increase steadily toward the core, due to the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism. At the "surface" pressure level of 10 bars, the temperature is around 340 K (67 °C; 152 °F). At the phase transition region where hydrogen—heated beyond its critical point—becomes metallic, it is believed the temperature is 10,000 K (9,700 °C; 17,500 °F) and the pressure is 200 GPa. The temperature at the core boundary is estimated to be 36,000 K (35,700 °C; 64,300 °F) and the interior pressure is roughly 3,000–4,500 GPa.[30]

This cut-away illustrates a model of the interior of Jupiter, with a rocky core overlaid by a deep layer of liquid metallic hydrogen.

Atmosphere

Jupiter has the largest planetary atmosphere in the Solar System, spanning over 5,000 km (3,107 mi) in altitude.[40][41] As Jupiter has no surface, the base of its atmosphere is usually considered to be the point at which atmospheric pressure is equal to 1 MPa (10 bar), or ten times surface pressure on Earth.[40]Cloud layers

This view of Jupiter's Great Red Spot and its surroundings was obtained by Voyager 1 on February 25, 1979, when the spacecraft was 9.2 million km (5.7 million mi) from Jupiter. The white oval storm directly below the Great Red Spot is approximately the same diameter as Earth.

Jupiter is perpetually covered with clouds composed of ammonia crystals and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide. The clouds are located in the tropopause and are arranged into bands of different latitudes, known as tropical regions. These are sub-divided into lighter-hued zones and darker belts. The interactions of these conflicting circulation patterns cause storms and turbulence. Wind speeds of 100 m/s (360 km/h) are common in zonal jets.[42] The zones have been observed to vary in width, color and intensity from year to year, but they have remained sufficiently stable for astronomers to give them identifying designations.[21]

This looping animation shows the movement of Jupiter's counter-rotating cloud bands. In this image, the planet's exterior is mapped onto a cylindrical projection. Animation at larger widths: 720 pixels, 1799 pixels.

The cloud layer is only about 50 km (31 mi) deep, and consists of at least two decks of clouds: a thick lower deck and a thin clearer region. There may also be a thin layer of water clouds underlying the ammonia layer, as evidenced by flashes of lightning detected in the atmosphere of Jupiter. This is caused by water's polarity, which makes it capable of creating the charge separation needed to produce lightning.[30] These electrical discharges can be up to a thousand times as powerful as lightning on the Earth.[43] The water clouds can form thunderstorms driven by the heat rising from the interior.[44]

The orange and brown coloration in the clouds of Jupiter are caused by upwelling compounds that change color when they are exposed to ultraviolet light from the Sun. The exact makeup remains uncertain, but the substances are believed to be phosphorus, sulfur or possibly hydrocarbons.[30][45] These colorful compounds, known as chromophores, mix with the warmer, lower deck of clouds. The zones are formed when rising convection cells form crystallizing ammonia that masks out these lower clouds from view.[46]

Jupiter's low axial tilt means that the poles constantly receive less solar radiation than at the planet's equatorial region. Convection within the interior of the planet transports more energy to the poles, balancing out the temperatures at the cloud layer.[21]

Great Red Spot and other vortices

The best known feature of Jupiter is the Great Red Spot, a persistent anticyclonic storm that is larger than Earth, located 22° south of the equator. Latest evidence by the Hubble Space Telescope shows there are three "red spots" adjacent to the Great Red Spot[48] It is known to have been in existence since at least 1831,[49] and possibly since 1665.[50][51] Mathematical models suggest that the storm is stable and may be a permanent feature of the planet.[52] The storm is large enough to be visible through Earth-based telescopes with an aperture of 12 cm or larger.[53]

Time-lapse sequence (over 1 month) from the approach of Voyager 1 to Jupiter, showing the motion of atmospheric bands, and circulation of the Great Red Spot.

Storms such as this are common within the turbulent atmospheres of giant planets. Jupiter also has white ovals and brown ovals, which are lesser unnamed storms. White ovals tend to consist of relatively cool clouds within the upper atmosphere. Brown ovals are warmer and located within the "normal cloud layer". Such storms can last as little as a few hours or stretch on for centuries.

Even before Voyager proved that the feature was a storm, there was strong evidence that the spot could not be associated with any deeper feature on the planet's surface, as the Spot rotates differentially with respect to the rest of the atmosphere, sometimes faster and sometimes more slowly. During its recorded history it has traveled several times around the planet relative to any possible fixed rotational marker below it.

In 2000, an atmospheric feature formed in the southern hemisphere that is similar in appearance to the Great Red Spot, but smaller. This was created when several smaller, white oval-shaped storms merged to form a single feature—these three smaller white ovals were first observed in 1938. The merged feature was named Oval BA, and has been nicknamed Red Spot Junior. It has since increased in intensity and changed color from white to red.[57][58][59]

Planetary rings

Magnetosphere

Aurora on Jupiter. Three bright dots are created by magnetic flux tubes that connect to the Jovian moons Io (on the left), Ganymede (on the bottom) and Europa (also on the bottom). In addition, the very bright almost circular region, called the main oval, and the fainter polar aurora can be seen.

Jupiter's magnetic field is 14 times as strong as the Earth's, ranging from 4.2 gauss (0.42 mT) at the equator to 10–14 gauss (1.0–1.4 mT) at the poles, making it the strongest in the Solar System (except for sunspots).[46] This field is believed to be generated by eddy currents—swirling movements of conducting materials—within the liquid metallic hydrogen core. The volcanoes on the moon Io emit large amounts of sulfur dioxide forming a gas torus along the moon's orbit. The gas is ionized in the magnetosphere producing sulfur and oxygen ions. They, together with hydrogen ions originating from the atmosphere of Jupiter, form a plasma sheet in Jupiter's equatorial plane. The plasma in the sheet co-rotates with the planet causing deformation of the dipole magnetic field into that of magnetodisk. Electrons within the plasma sheet generate a strong radio signature that produces bursts in the range of 0.6–30 MHz.[63]

At about 75 Jupiter radii from the planet, the interaction of the magnetosphere with the solar wind generates a bow shock. Surrounding Jupiter's magnetosphere is a magnetopause, located at the inner edge of a magnetosheath—a region between it and the bow shock. The solar wind interacts with these regions, elongating the magnetosphere on Jupiter's lee side and extending it outward until it nearly reaches the orbit of Saturn. The four largest moons of Jupiter all orbit within the magnetosphere, which protects them from the solar wind.[30]

The magnetosphere of Jupiter is responsible for intense episodes of radio emission from the planet's polar regions. Volcanic activity on the Jovian moon Io (see below) injects gas into Jupiter's magnetosphere, producing a torus of particles about the planet. As Io moves through this torus, the interaction generates Alfvén waves that carry ionized matter into the polar regions of Jupiter. As a result, radio waves are generated through a cyclotron maser mechanism, and the energy is transmitted out along a cone-shaped surface. When the Earth intersects this cone, the radio emissions from Jupiter can exceed the solar radio output.[64]

Orbit and rotation

Jupiter is the only planet that has a center of mass with the Sun that lies outside the volume of the Sun, though by only 7% of the Sun's radius.[65] The average distance between Jupiter and the Sun is 778 million km (about 5.2 times the average distance from the Earth to the Sun, or 5.2 AU) and it completes an orbit every 11.86 years. This is two-fifths the orbital period of Saturn, forming a 5:2 orbital resonance between the two largest planets in the Solar System.[66] The elliptical orbit of Jupiter is inclined 1.31° compared to the Earth. Because of an eccentricity of 0.048, the distance from Jupiter and the Sun varies by 75 million km between perihelion and aphelion, or the nearest and most distant points of the planet along the orbital path respectively.

The axial tilt of Jupiter is relatively small: only 3.13°. As a result this planet does not experience significant seasonal changes, in contrast to Earth and Mars for example.[67]

Jupiter's rotation is the fastest of all the Solar System's planets, completing a rotation on its axis in slightly less than ten hours; this creates an equatorial bulge easily seen through an Earth-based amateur telescope. The planet is shaped as an oblate spheroid, meaning that the diameter across its equator is longer than the diameter measured between its poles. On Jupiter, the equatorial diameter is 9,275 km (5,763 mi) longer than the diameter measured through the poles.[39]

Because Jupiter is not a solid body, its upper atmosphere undergoes differential rotation. The rotation of Jupiter's polar atmosphere is about 5 minutes longer than that of the equatorial atmosphere; three systems are used as frames of reference, particularly when graphing the motion of atmospheric features. System I applies from the latitudes 10° N to 10° S; its period is the planet's shortest, at 9h 50m 30.0s. System II applies at all latitudes north and south of these; its period is 9h 55m 40.6s. System III was first defined by radio astronomers, and corresponds to the rotation of the planet's magnetosphere; its period is Jupiter's official rotation.[68]

Observation

Jupiter is usually the fourth brightest object in the sky (after the Sun, the Moon and Venus);[46] at times Mars appears brighter than Jupiter. Depending on Jupiter's position with respect to the Earth, it can vary in visual magnitude from as bright as −2.9 at opposition down to −1.6 during conjunction with the Sun. The angular diameter of Jupiter likewise varies from 50.1 to 29.8 arc seconds.[3] Favorable oppositions occur when Jupiter is passing through perihelion, an event that occurs once per orbit. As Jupiter approached perihelion in March 2011, there was a favorable opposition in September 2010.[69]

Earth overtakes Jupiter every 398.9 days as it orbits the Sun, a duration called the synodic period. As it does so, Jupiter appears to undergo retrograde motion with respect to the background stars. That is, for a period Jupiter seems to move backward in the night sky, performing a looping motion.

Jupiter's 12-year orbital period corresponds to the dozen astrological signs of the zodiac, and may have been the historical origin of the signs.[21] That is, each time Jupiter reaches opposition it has advanced eastward by about 30°, the width of a zodiac sign.

Because the orbit of Jupiter is outside the Earth's, the phase angle of Jupiter as viewed from the Earth never exceeds 11.5°. That is, the planet always appears nearly fully illuminated when viewed through Earth-based telescopes. It was only during spacecraft missions to Jupiter that crescent views of the planet were obtained.[70] A small telescope will usually show Jupiter's four Galilean moons and the prominent cloud belts across Jupiter's atmosphere.[71] A large telescope will show Jupiter's Great Red Spot when it faces the Earth.

Research and exploration

Pre-telescopic research

The observation of Jupiter dates back to the Babylonian astronomers of the 7th or 8th century BC.[72] The Chinese historian of astronomy, Xi Zezong, has claimed that Gan De, a Chinese astronomer, made the discovery of one of Jupiter's moons in 362 BC with the unaided eye. If accurate, this would predate Galileo's discovery by nearly two millennia.[73][74] In his 2nd century work the Almagest, the Hellenistic astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus constructed a geocentric planetary model based on deferents and epicycles to explain Jupiter's motion relative to the Earth, giving its orbital period around the Earth as 4332.38 days, or 11.86 years.[75] In 499, Aryabhata, a mathematician-astronomer from the classical age of Indian mathematics and astronomy, also used a geocentric model to estimate Jupiter's period as 4332.2722 days, or 11.86 years.[76]

Ground-based telescope research

In 1610, Galileo Galilei discovered the four largest moons of Jupiter—Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto (now known as the Galilean moons)—using a telescope; thought to be the first telescopic observation of moons other than Earth's. Galileo's was also the first discovery of a celestial motion not apparently centered on the Earth. It was a major point in favor of Copernicus' heliocentric theory of the motions of the planets; Galileo's outspoken support of the Copernican theory placed him under the threat of the Inquisition.[77]During the 1660s, Cassini used a new telescope to discover spots and colorful bands on Jupiter and observed that the planet appeared oblate; that is, flattened at the poles. He was also able to estimate the rotation period of the planet.[16] In 1690 Cassini noticed that the atmosphere undergoes differential rotation.[30]

False-color detail of Jupiter's atmosphere, imaged by Voyager 1, showing the Great Red Spot and a passing white oval.

The Great Red Spot, a prominent oval-shaped feature in the southern hemisphere of Jupiter, may have been observed as early as 1664 by Robert Hooke and in 1665 by Giovanni Cassini, although this is disputed. The pharmacist Heinrich Schwabe produced the earliest known drawing to show details of the Great Red Spot in 1831.[78]

The Red Spot was reportedly lost from sight on several occasions between 1665 and 1708 before becoming quite conspicuous in 1878. It was recorded as fading again in 1883 and at the start of the 20th century.[79]

Both Giovanni Borelli and Cassini made careful tables of the motions of the Jovian moons, allowing predictions of the times when the moons would pass before or behind the planet. By the 1670s, it was observed that when Jupiter was on the opposite side of the Sun from the Earth, these events would occur about 17 minutes later than expected. Ole Rømer deduced that sight is not instantaneous (a conclusion that Cassini had earlier rejected),[16] and this timing discrepancy was used to estimate the speed of light.[80]

In 1892, E. E. Barnard observed a fifth satellite of Jupiter with the 36-inch (910 mm) refractor at Lick Observatory in California. The discovery of this relatively small object, a testament to his keen eyesight, quickly made him famous. The moon was later named Amalthea.[81] It was the last planetary moon to be discovered directly by visual observation.[82] An additional eight satellites were subsequently discovered before the flyby of the Voyager 1 probe in 1979.

In 1932, Rupert Wildt identified absorption bands of ammonia and methane in the spectra of Jupiter.[83]

Three long-lived anticyclonic features termed white ovals were observed in 1938. For several decades they remained as separate features in the atmosphere, sometimes approaching each other but never merging. Finally, two of the ovals merged in 1998, then absorbed the third in 2000, becoming Oval BA.[84]

Radiotelescope research

In 1955, Bernard Burke and Kenneth Franklin detected bursts of radio signals coming from Jupiter at 22.2 MHz.[30] The period of these bursts matched the rotation of the planet, and they were also able to use this information to refine the rotation rate. Radio bursts from Jupiter were found to come in two forms: long bursts (or L-bursts) lasting up to several seconds, and short bursts (or S-bursts) that had a duration of less than a hundredth of a second.[85]Scientists discovered that there were three forms of radio signals transmitted from Jupiter.

- Decametric radio bursts (with a wavelength of tens of meters) vary with the rotation of Jupiter, and are influenced by interaction of Io with Jupiter's magnetic field.[86]

- Decimetric radio emission (with wavelengths measured in centimeters) was first observed by Frank Drake and Hein Hvatum in 1959.[30] The origin of this signal was from a torus-shaped belt around Jupiter's equator. This signal is caused by cyclotron radiation from electrons that are accelerated in Jupiter's magnetic field.[87]

- Thermal radiation is produced by heat in the atmosphere of Jupiter.[30]

Exploration with space probes

Since 1973 a number of automated spacecraft have visited Jupiter, most notably the Pioneer 10 space probe, the first spacecraft to get close enough to Jupiter to send back revelations about the properties and phenomena of the Solar System's largest planet.[88][89] Flights to other planets within the Solar System are accomplished at a cost in energy, which is described by the net change in velocity of the spacecraft, or delta-v. Entering a Hohmann transfer orbit from Earth to Jupiter from low Earth orbit requires a delta-v of 6.3 km/s[90] which is comparable to the 9.7 km/s delta-v needed to reach low Earth orbit.[91] Fortunately, gravity assists through planetary flybys can be used to reduce the energy required to reach Jupiter, albeit at the cost of a significantly longer flight duration.[92]Flyby missions

| Spacecraft | Closest approach |

Distance |

|---|---|---|

| Pioneer 10 | December 3, 1973 | 130,000 km |

| Pioneer 11 | December 4, 1974 | 34,000 km |

| Voyager 1 | March 5, 1979 | 349,000 km |

| Voyager 2 | July 9, 1979 | 570,000 km |

| Ulysses | February 8, 1992[93] | 408,894 km |

| February 4, 2004[93] | 120,000,000 km | |

| Cassini | December 30, 2000 | 10,000,000 km |

| New Horizons | February 28, 2007 | 2,304,535 km |

Six years later, the Voyager missions vastly improved the understanding of the Galilean moons and discovered Jupiter's rings. They also confirmed that the Great Red Spot was anticyclonic. Comparison of images showed that the Red Spot had changed hue since the Pioneer missions, turning from orange to dark brown. A torus of ionized atoms was discovered along Io's orbital path, and volcanoes were found on the moon's surface, some in the process of erupting. As the spacecraft passed behind the planet, it observed flashes of lightning in the night side atmosphere.[15][21]

The next mission to encounter Jupiter, the Ulysses solar probe, performed a flyby maneuver to attain a polar orbit around the Sun. During this pass the spacecraft conducted studies on Jupiter's magnetosphere. Since Ulysses has no cameras, no images were taken. A second flyby six years later was at a much greater distance.[93]

In 2000, the Cassini probe, en route to Saturn, flew by Jupiter and provided some of the highest-resolution images ever made of the planet. On December 19, 2000, the spacecraft captured an image of the moon Himalia, but the resolution was too low to show surface details.[95]

The New Horizons probe, en route to Pluto, flew by Jupiter for gravity assist. Its closest approach was on February 28, 2007.[96] The probe's cameras measured plasma output from volcanoes on Io and studied all four Galilean moons in detail, as well as making long-distance observations of the outer moons Himalia and Elara.[97] Imaging of the Jovian system began September 4, 2006.[98][99]

Galileo mission

Jupiter as seen by the space probe Cassini.

So far the only spacecraft to orbit Jupiter is the Galileo orbiter, which went into orbit around Jupiter on December 7, 1995.[26] It orbited the planet for over seven years, conducting multiple flybys of all the Galilean moons and Amalthea. The spacecraft also witnessed the impact of Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 as it approached Jupiter in 1994, giving a unique vantage point for the event. While the information gained about the Jovian system from Galileo was extensive, its originally designed capacity was limited by the failed deployment of its high-gain radio transmitting antenna.[100]

A 340-kilogram titanium atmospheric probe was released from the spacecraft in July 1995, entering Jupiter's atmosphere on December 7.[26] It parachuted through 150 km (93 mi) of the atmosphere at speed of about 2,575 km/h (1600 mph)[26] and collected data for 57.6 minutes before it was crushed by the pressure (about 23 times Earth normal, at a temperature of 153 °C).[101] It would have melted thereafter, and possibly vaporized. The Galileo orbiter itself experienced a more rapid version of the same fate when it was deliberately steered into the planet on September 21, 2003, at a speed of over 50 km/s, to avoid any possibility of it crashing into and possibly contaminating Europa—a moon which has been hypothesized to have the possibility of harboring life.[100]

Data from this mission revealed that hydrogen composes up to 90% of Jupiter's atmosphere.[26] The temperatures data recorded was more than 300°C (>570°F) and the windspeed measured more than 644 kmph (>400 mph) before the probes vapourised.[26]

Future probes

NASA has a mission underway to study Jupiter in detail from a polar orbit. Named Juno, the spacecraft launched in August 2011, and will arrive in late 2016.[102] The next planned mission to the Jovian system will be the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE), due to launch in 2022.[103]Canceled missions

Because of the possibility of subsurface liquid oceans on Jupiter's moons Europa, Ganymede and Callisto, there has been great interest in studying the icy moons in detail. Funding difficulties have delayed progress. NASA's JIMO (Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter) was cancelled in 2005.[104] A subsequent proposal for a joint NASA/ESA mission, called EJSM/Laplace, was developed with a provisional launch date around 2020. EJSM/Laplace would have consisted of the NASA-led Jupiter Europa Orbiter, and the ESA-led Jupiter Ganymede Orbiter.[105] However by April 2011, ESA had formally ended the partnership citing budget issues at NASA and the consequences on the mission timetable. Instead ESA planned to go ahead with a European-only mission to compete in its L1 Cosmic Vision selection.[106]Moons

Jupiter has 67 natural satellites.[107] Of these, 51 are less than 10 kilometres in diameter and have only been discovered since 1975. The four largest moons, visible from Earth with binoculars on a clear night, known as the "Galilean moons", are Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

Galilean moons

The orbits of Io, Europa, and Ganymede, some of the largest satellites in the Solar System, form a pattern known as a Laplace resonance; for every four orbits that Io makes around Jupiter, Europa makes exactly two orbits and Ganymede makes exactly one. This resonance causes the gravitational effects of the three large moons to distort their orbits into elliptical shapes, since each moon receives an extra tug from its neighbors at the same point in every orbit it makes. The tidal force from Jupiter, on the other hand, works to circularize their orbits.[108]

The eccentricity of their orbits causes regular flexing of the three moons' shapes, with Jupiter's gravity stretching them out as they approach it and allowing them to spring back to more spherical shapes as they swing away. This tidal flexing heats the moons' interiors by friction. This is seen most dramatically in the extraordinary volcanic activity of innermost Io (which is subject to the strongest tidal forces), and to a lesser degree in the geological youth of Europa's surface (indicating recent resurfacing of the moon's exterior).

| Name | IPA | Diameter | Mass | Orbital radius | Orbital period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| km | % | kg | % | km | % | days | % | ||

| Io | ˈaɪ.oʊ | 3643 | 105 | 8.9×1022 | 120 | 421,700 | 110 | 1.77 | 7 |

| Europa | jʊˈroʊpə | 3122 | 90 | 4.8×1022 | 65 | 671,034 | 175 | 3.55 | 13 |

| Ganymede | ˈɡænimiːd | 5262 | 150 | 14.8×1022 | 200 | 1,070,412 | 280 | 7.15 | 26 |

| Callisto | kəˈlɪstoʊ | 4821 | 140 | 10.8×1022 | 150 | 1,882,709 | 490 | 16.69 | 61 |

Classification of moons

Before the discoveries of the Voyager missions, Jupiter's moons were arranged neatly into four groups of four, based on commonality of their orbital elements. Since then, the large number of new small outer moons has complicated this picture. There are now thought to be six main groups, although some are more distinct than others.

A basic sub-division is a grouping of the eight inner regular moons, which have nearly circular orbits near the plane of Jupiter's equator and are believed to have formed with Jupiter. The remainder of the moons consist of an unknown number of small irregular moons with elliptical and inclined orbits, which are believed to be captured asteroids or fragments of captured asteroids. Irregular moons that belong to a group share similar orbital elements and thus may have a common origin, perhaps as a larger moon or captured body that broke up.[109][110]

| Regular moons | |

|---|---|

| Inner group | The inner group of four small moons all have diameters of less than 200 km, orbit at radii less than 200,000 km, and have orbital inclinations of less than half a degree. |

| Galilean moons[111] | These four moons, discovered by Galileo Galilei and by Simon Marius in parallel, orbit between 400,000 and 2,000,000 km, and include some of the largest moons in the Solar System. |

| Irregular moons | |

| Themisto | This is a single moon belonging to a group of its own, orbiting halfway between the Galilean moons and the Himalia group. |

| Himalia group | A tightly clustered group of moons with orbits around 11,000,000–12,000,000 km from Jupiter. |

| Carpo | Another isolated case; at the inner edge of the Ananke group, it orbits Jupiter in prograde direction. |

| Ananke group | This retrograde orbit group has rather indistinct borders, averaging 21,276,000 km from Jupiter with an average inclination of 149 degrees. |

| Carme group | A fairly distinct retrograde group that averages 23,404,000 km from Jupiter with an average inclination of 165 degrees. |

| Pasiphaë group | A dispersed and only vaguely distinct retrograde group that covers all the outermost moons. |

Interaction with the Solar System

Along with the Sun, the gravitational influence of Jupiter has helped shape the Solar System. The orbits of most of the system's planets lie closer to Jupiter's orbital plane than the Sun's equatorial plane (Mercury is the only planet that is closer to the Sun's equator in orbital tilt), the Kirkwood gaps in the asteroid belt are mostly caused by Jupiter, and the planet may have been responsible for the Late Heavy Bombardment of the inner Solar System's history.[112]Along with its moons, Jupiter's gravitational field controls numerous asteroids that have settled into the regions of the Lagrangian points preceding and following Jupiter in its orbit around the Sun. These are known as the Trojan asteroids, and are divided into Greek and Trojan "camps" to commemorate the Iliad. The first of these, 588 Achilles, was discovered by Max Wolf in 1906; since then more than two thousand have been discovered.[113] The largest is 624 Hektor.

Most short-period comets belong to the Jupiter family—defined as comets with semi-major axes smaller than Jupiter's. Jupiter family comets are believed to form in the Kuiper belt outside the orbit of Neptune. During close encounters with Jupiter their orbits are perturbed into a smaller period and then circularized by regular gravitational interaction with the Sun and Jupiter.[114]

Impacts

Hubble image taken on July 23 showing a blemish of about 5,000 miles long left by the 2009 Jupiter impact.[115]

Jupiter has been called the Solar System's vacuum cleaner,[116] because of its immense gravity well and location near the inner Solar System. It receives the most frequent comet impacts of the Solar System's planets.[117] It was thought that the planet served to partially shield the inner system from cometary bombardment.[26] Recent computer simulations suggest that Jupiter does not cause a net decrease in the number of comets that pass through the inner Solar System, as its gravity perturbs their orbits inward in roughly the same numbers that it accretes or ejects them.[118] This topic remains controversial among astronomers, as some believe it draws comets towards Earth from the Kuiper belt while others believe that Jupiter protects Earth from the alleged Oort cloud.[119] Jupiter experiences about 200 times more asteroid and comet impacts than Earth.[26]

A 1997 survey of historical astronomical drawings suggested that the astronomer Cassini may have recorded an impact scar in 1690. The survey determined eight other candidate observations had low or no possibilities of an impact.[120] A fireball was photographed by Voyager 1 during its Jupiter encounter in March 1979.[121] During the period July 16, 1994, to July 22, 1994, over 20 fragments from the comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 (SL9, formally designated D/1993 F2) collided with Jupiter's southern hemisphere, providing the first direct observation of a collision between two Solar System objects. This impact provided useful data on the composition of Jupiter's atmosphere.[122][123]

On July 19, 2009, an impact site was discovered at approximately 216 degrees longitude in System 2.[124][125] This impact left behind a black spot in Jupiter's atmosphere, similar in size to Oval BA. Infrared observation showed a bright spot where the impact took place, meaning the impact warmed up the lower atmosphere in the area near Jupiter's south pole.[126]

A fireball, smaller than the previous observed impacts, was detected on June 3, 2010, by Anthony Wesley, an amateur astronomer in Australia, and was later discovered to have been captured on video by another amateur astronomer in the Philippines.[127] Yet another fireball was seen on August 20, 2010.[128]

On September 10, 2012, another fireball was detected.[121][129]

Possibility of life

In 1953, the Miller–Urey experiment demonstrated that a combination of lightning and the chemical compounds that existed in the atmosphere of a primordial Earth could form organic compounds (including amino acids) that could serve as the building blocks of life. The simulated atmosphere included water, methane, ammonia and molecular hydrogen; all molecules still found in the atmosphere of Jupiter. The atmosphere of Jupiter has a strong vertical air circulation, which would carry these compounds down into the lower regions. The higher temperatures within the interior of the atmosphere breaks down these chemicals, which would hinder the formation of Earth-like life.[130]It is considered highly unlikely that there is any Earth-like life on Jupiter, as there is only a small amount of water in the atmosphere and any possible solid surface deep within Jupiter would be under extraordinary pressures. In 1976, before the Voyager missions, it was hypothesized that ammonia or water-based life could evolve in Jupiter's upper atmosphere. This hypothesis is based on the ecology of terrestrial seas which have simple photosynthetic plankton at the top level, fish at lower levels feeding on these creatures, and marine predators which hunt the fish.[131][132]

The possible presence of underground oceans on some of Jupiter's moons has led to speculation that the presence of life is more likely there.

Mythology

The planet Jupiter has been known since ancient times. It is visible to the naked eye in the night sky and can occasionally be seen in the daytime when the Sun is low.[133] To the Babylonians, this object represented their god Marduk. They used the roughly 12-year orbit of this planet along the ecliptic to define the constellations of their zodiac.[21][134]

The Romans named it after Jupiter (Latin: Iuppiter, Iūpiter) (also called Jove), the principal god of Roman mythology, whose name comes from the Proto-Indo-European vocative compound *Dyēu-pəter (nominative: *Dyēus-pətēr, meaning "O Father Sky-God", or "O Father Day-God").[135] In turn, Jupiter was the counterpart to the mythical Greek Zeus (Ζεύς), also referred to as Dias (Δίας), the planetary name of which is retained in modern Greek.[136]

The astronomical symbol for the planet,

Jovian is the adjectival form of Jupiter. The older adjectival form jovial, employed by astrologers in the Middle Ages, has come to mean "happy" or "merry," moods ascribed to Jupiter's astrological influence.[138]

The Chinese, Korean and Japanese referred to the planet as the "wood star" (Chinese: 木星; pinyin: mùxīng), based on the Chinese Five Elements.[139] Chinese Taoism personified it as the Fu star. The Greeks called it Φαέθων, Phaethon, "blazing." In Vedic Astrology, Hindu astrologers named the planet after Brihaspati, the religious teacher of the gods, and often called it "Guru", which literally means the "Heavy One."[140] In the English language, Thursday is derived from "Thor's day", with Thor associated with the planet Jupiter in Germanic mythology.[141]

In the Central Asian-Turkic myths, Jupiter called as a "Erendiz/Erentüz", which means "eren(?)+yultuz(star)". There are many theories about meaning of "eren". Also, these peoples calculated the period of the orbit of Jupiter as 11 years and 300 days. They believed that some social and natural events connected to Erentüz's movements on the sky.[142]