Heavy metals is a controversial and ambiguous term for metallic elements with relatively high densities, atomic weights, or atomic numbers. The criteria used, and whether metalloids are included, vary depending on the author and context, and arguably, the term "heavy metal" should be avoided. A heavy metal may be defined on the basis of density, atomic number, or chemical behaviour. More specific definitions have been published, none of which has been widely accepted. The definitions surveyed in this article encompass up to 96 of the 118 known chemical elements; only mercury, lead, and bismuth meet all of them. Despite this lack of agreement, the term (plural or singular) is widely used in science. A density of more than 5 g/cm3 is sometimes quoted as a commonly used criterion and is used in the body of this article.

The earliest known metals—common metals such as iron, copper, and tin, and precious metals such as silver, gold, and platinum—are heavy metals. From 1809 onward, light metals, such as magnesium, aluminium, and titanium, were discovered, as well as less well-known heavy metals, including gallium, thallium, and hafnium.

Some heavy metals are either essential nutrients (typically iron, cobalt, copper, and zinc), or relatively harmless (such as ruthenium, silver, and indium), but can be toxic in larger amounts or certain forms. Other heavy metals, such as arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead, are highly poisonous. Potential sources of heavy-metal poisoning include mining, tailings, smelting, industrial waste, agricultural runoff, occupational exposure, paints, and treated timber.

Physical and chemical characterisations of heavy metals need to be treated with caution, as the metals involved are not always consistently defined. Heavy metals, as well as being relatively dense, tend to be less reactive than lighter metals, and have far fewer soluble sulfides and hydroxides. While distinguishing a heavy metal such as tungsten from a lighter metal such as sodium is relatively easy, a few heavy metals, such as zinc, mercury, and lead, have some of the characteristics of lighter metals, and lighter metals, such as beryllium, scandium, and titanium, have some of the characteristics of heavier metals.

Heavy metals are relatively rare in the Earth's crust, but are present in many aspects of modern life. They are used in, for example, golf clubs, cars, antiseptics, self-cleaning ovens, plastics, solar panels, mobile phones, and particle accelerators.

Definitions

Controversial terminology

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), which standardizes nomenclature, says "the term 'heavy metals' is both meaningless and misleading". The IUPAC report focuses on the legal and toxicological implications of describing "heavy metals" as toxins when no scientific evidence supports a connection. The density implied by the adjective "heavy" has almost no biological consequences, and pure metals are rarely the biologically active form. This characterization has been echoed by numerous reviews. The most widely used toxicology textbook, Casarett and Doull’s Toxicology uses "toxic metal", not "heavy metal". Nevertheless, there are scientific and science related articles which continue to use "heavy metal" as a term for toxic substances. To be an acceptable term in scientific papers, a strict definition has been encouraged.

Use outside toxicology

| Heat map of heavy metals in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | |||||||||||

| 1 | H | He | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | ||||||||||

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Tc | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||||||||||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | Po | At | Rn | ||||||||||

| 7 | Fr | Ra | Lr | Rf | Db | Sg | Bh | Hs | Mt | Ds | Rg | Cn | Nh | Fl | Mc | Lv | Ts | Og | ||||||||||

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Pm | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | |||||||||||||||

| Ac | Th | Pa | U | Np | Pu | Am | Cm | Bk | Cf | Es | Fm | Md | No | |||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| This

table shows the number of heavy metal criteria met by each metal, out

of the ten criteria listed in this section i.e. two based on density, three on atomic weight, two on atomic number, and three on chemical behaviour. It illustrates the lack of agreement surrounding the concept, with the possible exception of mercury, lead, and bismuth. Six elements near the end of periods (rows) 4 to 7 sometimes considered metalloids are treated here as metals: they are germanium (Ge), arsenic (As), selenium (Se), antimony (Sb), tellurium (Te), and astatine (At).Oganesson (Og) is treated as a nonmetal.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Even in applications other than toxicity, no widely agreed criterion-based definition of a heavy metal exists. Reviews have recommended that it not be used. Different meanings may be attached to the term, depending on the context. For example, a heavy metal may be defined on the basis of density, and the distinguishing criterion might be atomic number or chemical behaviour.

Density criteria range from above 3.5 g/cm3 to above 7 g/cm3. Atomic weight definitions can range from greater than sodium (atomic weight 22.98); greater than 40 (excluding s- and f-block metals, hence starting with scandium); or more than 200, i.e. from mercury onwards. Atomic numbers are sometimes capped at 92 (uranium). Definitions based on atomic number have been criticised for including metals with low densities. For example, rubidium in group (column) 1 of the periodic table has an atomic number of 37, but a density of only 1.532 g/cm3, which is below the threshold figure used by other authors. The same problem may occur with definitions which are based on atomic weight.

The United States Pharmacopeia includes a test for heavy metals that involves precipitating metallic impurities as their coloured sulfides. On the basis of this type of chemical test, the group would include the transition metals and post-transition metals.

A different chemistry-based approach advocates replacing the term "heavy metal" with two groups of metals and a gray area. Class A metal ions prefer oxygen donors; class B ions prefer nitrogen or sulfur donors; and borderline or ambivalent ions show either class A or B characteristics, depending on the circumstances. The distinction between the class A metals and the other two categories is sharp. The class A and class B terminology is analogous to the "hard acid" and "soft base" terminology sometimes used to refer to the behaviour of metal ions in inorganic systems. The system groups the elements by where is the metal ion electronegativity and is its ionic radius. This index gauges the importance of covalent interactions vs ionic interactions for a given metal ion. This scheme has been applied to analyze biologically active metals in sea water for example, but it has not been widely adopted.

Origins and use of the term

The heaviness of naturally occurring metals such as gold, copper, and iron may have been noticed in prehistory and, in light of their malleability, led to the first attempts to craft metal ornaments, tools, and weapons.

In 1817, German chemist Leopold Gmelin divided the elements into nonmetals, light metals, and heavy metals. Light metals had densities of 0.860–5.0 g/cm3; heavy metals 5.308–22.000. The term heavy metal is sometimes used interchangeably with the term "heavy element". For example, in discussing the history of nuclear chemistry, Magee noted that the actinides were once thought to represent a new heavy-element transition group, whereas Seaborg and co-workers "favoured ... a heavy metal rare-earth like series ...".

The counterparts to the heavy metals, the light metals, are defined by the Minerals, Metals and Materials Society as including "the traditional (aluminium, magnesium, beryllium, titanium, lithium, and other reactive metals) and emerging light metals (composites, laminates, etc.)"

Biological role

| Element | Milligrams | |

|---|---|---|

| Iron | 4000 | |

| Zinc | 2500 | |

| Lead | 120 | |

| Copper | 70 | |

| Tin | 30 | |

| Vanadium | 20 | |

| Cadmium | 20 | |

| Nickel | 15 | |

| Selenium | 14 | |

| Manganese | 12 | |

| Other | 200 | |

| Total | 7000 | |

Trace amounts of some heavy metals, mostly in period 4, are required for certain biological processes. These are iron and copper (oxygen and electron transport); cobalt (complex syntheses and cell metabolism); vanadium and manganese (enzyme regulation or functioning); chromium (glucose utilisation); nickel (cell growth); arsenic (metabolic growth in some animals and possibly in humans) and selenium (antioxidant functioning and hormone production). Periods 5 and 6 contain fewer essential heavy metals, consistent with the general pattern that heavier elements tend to be less abundant and that scarcer elements are less likely to be nutritionally essential. In period 5, molybdenum is required for the catalysis of redox reactions; cadmium is used by some marine diatoms for the same purpose; and tin may be required for growth in a few species. In period 6, tungsten is required by some archaea and bacteria for metabolic processes. A deficiency of any of these period 4–6 essential heavy metals may increase susceptibility to heavy metal poisoning (conversely, an excess may also have adverse biological effects).

An average 70 kg (150 lb) human body is about 0.01% heavy metals (~7 g (0.25 oz), equivalent to the weight of two dried peas, with iron at 4 g (0.14 oz), zinc at 2.5 g (0.088 oz), and lead at 0.12 g (0.0042 oz) comprising the three main constituents), 2% light metals (~1.4 kg (3.1 lb), the weight of a bottle of wine) and nearly 98% nonmetals (mostly water).

A few non-essential heavy metals have been observed to have biological effects. Gallium, germanium (a metalloid), indium, and most lanthanides can stimulate metabolism, and titanium promotes growth in plants (though it is not always considered a heavy metal).

Toxicity

Heavy metals are often assumed to be highly toxic or damaging to the environment and while some are, certain others are toxic only when taken in excess or encountered in certain forms. Inhalation of certain metals, either as fine dust or most commonly as fumes, can also result in a condition called metal fume fever.

Environmental heavy metals

Chromium, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, and lead have the greatest potential to cause harm on account of their extensive use, the toxicity of some of their combined or elemental forms, and their widespread distribution in the environment. Hexavalent chromium, for example, is highly toxic as are mercury vapour and many mercury compounds. These five elements have a strong affinity for sulfur; in the human body they usually bind, via thiol groups (–SH), to enzymes responsible for controlling the speed of metabolic reactions. The resulting sulfur-metal bonds inhibit the proper functioning of the enzymes involved; human health deteriorates, sometimes fatally. Chromium (in its hexavalent form) and arsenic are carcinogens; cadmium causes a degenerative bone disease; and mercury and lead damage the central nervous system.

-

Chromium crystals and 1 cm3 cube

-

Arsenic, sealed in a container to stop tarnishing

-

Cadmium bar and 1 cm3 cube

-

Mercury being poured into a petri dish

Lead is the most prevalent heavy metal contaminant. Levels in the aquatic environments of industrialised societies have

been estimated to be two to three times those of pre-industrial levels. As a component of tetraethyl lead, (CH

3CH

2)

4Pb, it was used extensively in gasoline from the 1930s until the 1970s. Although the use of leaded gasoline was largely phased out in North

America by 1996, soils next to roads built before this time retain high

lead concentrations. Later research demonstrated a statistically significant correlation

between the usage rate of leaded gasoline and violent crime in the

United States; taking into account a 22-year time lag (for the average

age of violent criminals), the violent crime curve virtually tracked the

lead exposure curve.

Other heavy metals noted for their potentially hazardous nature, usually as toxic environmental pollutants, include manganese (central nervous system damage); cobalt and nickel (carcinogens); copper (toxic for plants), zinc, selenium and silver (endocrine disruption, congenital disorders, or general toxic effects in fish, plants, birds, or other aquatic organisms); tin, as organotin (central nervous system damage); antimony (a suspected carcinogen); and thallium (central nervous system damage).

Other heavy metals

A few other non-essential heavy metals have one or more toxic forms. Kidney failure and fatalities have been recorded arising from the ingestion of germanium dietary supplements (~15 to 300 g in total consumed over a period of two months to three years). Exposure to osmium tetroxide (OsO4) may cause permanent eye damage and can lead to respiratory failure and death. Indium salts are toxic if more than few milligrams are ingested and will affect the kidneys, liver, and heart. Cisplatin (PtCl2(NH3)2), an important drug used to kill cancer cells, is also a kidney and nerve poison. Bismuth compounds can cause liver damage if taken in excess; insoluble uranium compounds, as well as the dangerous radiation they emit, can cause permanent kidney damage.

Exposure sources

Heavy metals can degrade air, water, and soil quality, and subsequently cause health issues in plants, animals, and people, when they become concentrated as a result of industrial activities. Common sources of heavy metals in this context include vehicle emissions; motor oil; fertilisers; glassworking; incinerators; treated timber; aging water supply infrastructure; and microplastics floating in the world's oceans. Recent examples of heavy metal contamination and health risks include the occurrence of Minamata disease, in Japan (1932–1968; lawsuits ongoing as of 2016); the Bento Rodrigues dam disaster in Brazil, high levels of lead in drinking water supplied to the residents of Flint, Michigan, in the north-east of the United States and 2015 Hong Kong heavy metal in drinking water incidents.

Formation, abundance, occurrence, and extraction

| Heavy metals in the Earth's crust: | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| abundance and main occurrence or source | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | ||

| 1 | H | He | |||||||||||||||||

| 2 | Li | Be | B | C | N | O | F | Ne | |||||||||||

| 3 | Na | Mg | Al | Si | P | S | Cl | Ar | |||||||||||

| 4 | K | Ca | Sc | Ti | V | Cr | Mn | Fe | Co | Ni | Cu | Zn | Ga | Ge | As | Se | Br | Kr | |

| 5 | Rb | Sr | Y | Zr | Nb | Mo | Ru | Rh | Pd | Ag | Cd | In | Sn | Sb | Te | I | Xe | ||

| 6 | Cs | Ba | Lu | Hf | Ta | W | Re | Os | Ir | Pt | Au | Hg | Tl | Pb | Bi | ||||

| 7 | |||||||||||||||||||

| La | Ce | Pr | Nd | Sm | Eu | Gd | Tb | Dy | Ho | Er | Tm | Yb | |||||||

| Th | U | ||||||||||||||||||

Most abundant (56,300 ppm by weight)

|

Rare (0.01–0.99 ppm)

| ||||||||||||||||||

Abundant (100–999 ppm)

|

Very rare (0.0001–0.0099 ppm)

| ||||||||||||||||||

Uncommon (1–99 ppm)

|

|||||||||||||||||||

| Heavy metals left of the dividing line occur (or are sourced) mainly as lithophiles; those to the right, as chalcophiles except gold (a siderophile) and tin (a lithophile). | |||||||||||||||||||

Heavy metals up to the vicinity of iron (in the periodic table) are largely made via stellar nucleosynthesis. In this process, lighter elements from hydrogen to silicon undergo successive fusion reactions inside stars, releasing light and heat and forming heavier elements with higher atomic numbers.

Heavier heavy metals are not usually formed this way since fusion reactions involving such nuclei would consume rather than release energy. Rather, they are largely synthesised (from elements with a lower atomic number) by neutron capture, with the two main modes of this repetitive capture being the s-process and the r-process. In the s-process ("s" stands for "slow"), singular captures are separated by years or decades, allowing the less stable nuclei to beta decay, while in the r-process ("rapid"), captures happen faster than nuclei can decay. Therefore, the s-process takes a more or less clear path: for example, stable cadmium-110 nuclei are successively bombarded by free neutrons inside a star until they form cadmium-115 nuclei which are unstable and decay to form indium-115 (which is nearly stable, with a half-life 30,000 times the age of the universe). These nuclei capture neutrons and form indium-116, which is unstable, and decays to form tin-116, and so on. In contrast, there is no such path in the r-process. The s-process stops at bismuth due to the short half-lives of the next two elements, polonium and astatine, which decay to bismuth or lead. The r-process is so fast it can skip this zone of instability and go on to create heavier elements such as thorium and uranium.

Heavy metals condense in planets as a result of stellar evolution and destruction processes. Stars lose much of their mass when it is ejected late in their lifetimes, and sometimes thereafter as a result of a neutron star merger, thereby increasing the abundance of elements heavier than helium in the interstellar medium. When gravitational attraction causes this matter to coalesce and collapse, new stars and planets are formed.

The Earth's crust is made of approximately 5% of heavy metals by weight, with iron comprising 95% of this quantity. Light metals (~20%) and nonmetals (~75%) make up the other 95% of the crust. Despite their overall scarcity, heavy metals can become concentrated in economically extractable quantities as a result of mountain building, erosion, or other geological processes.

Heavy metals are found primarily as lithophiles (rock-loving) or chalcophiles (ore-loving). Lithophile heavy metals are mainly f-block elements and the more reactive of the d-block elements. They have a strong affinity for oxygen and mostly exist as relatively low density silicate minerals. Chalcophile heavy metals are mainly the less reactive d-block elements, and period 4–6 p-block metals and metalloids. They are usually found in (insoluble) sulfide minerals. Being denser than the lithophiles, hence sinking lower into the crust at the time of its solidification, the chalcophiles tend to be less abundant than the lithophiles.

In contrast, gold is a siderophile, or iron-loving element. It does not readily form compounds with either oxygen or sulfur. At the time of the Earth's formation, and as the most noble (inert) of metals, gold sank into the core due to its tendency to form high-density metallic alloys. Consequently, it is a relatively rare metal. Some other (less) noble heavy metals—molybdenum, rhenium, the platinum group metals (ruthenium, rhodium, palladium, osmium, iridium, and platinum), germanium, and tin—can be counted as siderophiles but only in terms of their primary occurrence in the Earth (core, mantle and crust), rather the crust. These metals otherwise occur in the crust, in small quantities, chiefly as chalcophiles (less so in their native form).

Concentrations of heavy metals below the crust are generally higher, with most being found in the largely iron-silicon-nickel core. Platinum, for example, comprises approximately 1 part per billion of the crust whereas its concentration in the core is thought to be nearly 6,000 times higher. Recent speculation suggests that uranium (and thorium) in the core may generate a substantial amount of the heat that drives plate tectonics and (ultimately) sustains the Earth's magnetic field.

Broadly speaking, and with some exceptions, lithophile heavy metals can be extracted from their ores by electrical or chemical treatments, while chalcophile heavy metals are obtained by roasting their sulphide ores to yield the corresponding oxides, and then heating these to obtain the raw metals. Radium occurs in quantities too small to be economically mined and is instead obtained from spent nuclear fuels. The chalcophile platinum group metals (PGM) mainly occur in small (mixed) quantities with other chalcophile ores. The ores involved need to be smelted, roasted, and then leached with sulfuric acid to produce a residue of PGM. This is chemically refined to obtain the individual metals in their pure forms. Compared to other metals, PGM are expensive due to their scarcity and high production costs.

Gold, a siderophile, is most commonly recovered by dissolving the ores in which it is found in a cyanide solution. The gold forms a dicyanoaurate(I), for example: 2 Au + H2O +½ O2 + 4 KCN → 2 K[Au(CN)2] + 2 KOH. Zinc is added to the mix and, being more reactive than gold, displaces the gold: 2 K[Au(CN)2] + Zn → K2[Zn(CN)4] + 2 Au. The gold precipitates out of solution as a sludge, and is filtered off and melted.

Uses

Some common uses of heavy metals depend on the general characteristics of metals such as electrical conductivity and reflectivity or the general characteristics of heavy metals such as density, strength, and durability. Other uses depend on the characteristics of the specific element, such as their biological role as nutrients or poisons or some other specific atomic properties. Examples of such atomic properties include: partly filled d- or f- orbitals (in many of the transition, lanthanide, and actinide heavy metals) that enable the formation of coloured compounds; the capacity of heavy metal ions (such as platinum, cerium or bismuth) to exist in different oxidation states and are used in catalysts; strong exchange interactions in 3d or 4f orbitals (in iron, cobalt, and nickel, or the lanthanide heavy metals) that give rise to magnetic effects; and high atomic numbers and electron densities that underpin their nuclear science applications. Typical uses of heavy metals can be broadly grouped into the following categories.

Weight- or density-based

Some uses of heavy metals, including in sport, mechanical engineering, military ordnance, and nuclear science, take advantage of their relatively high densities. In underwater diving, lead is used as a ballast; in handicap horse racing each horse must carry a specified lead weight, based on factors including past performance, so as to equalize the chances of the various competitors. In golf, tungsten, brass, or copper inserts in fairway clubs and irons lower the centre of gravity of the club making it easier to get the ball into the air; and golf balls with tungsten cores are claimed to have better flight characteristics. In fly fishing, sinking fly lines have a PVC coating embedded with tungsten powder, so that they sink at the required rate. In track and field sport, steel balls used in the hammer throw and shot put events are filled with lead in order to attain the minimum weight required under international rules. Tungsten was used in hammer throw balls at least up to 1980; the minimum size of the ball was increased in 1981 to eliminate the need for what was, at that time, an expensive metal (triple the cost of other hammers) not generally available in all countries. Tungsten hammers were so dense that they penetrated too deeply into the turf.

The higher the projectile density, the more effectively it can penetrate heavy armor plate ... Os, Ir, Pt, and Re ... are expensive ... U offers an appealing combination of high density, reasonable cost and high fracture toughness.

Structure–property relations

in nonferrous metals (2005, p. 16)

Heavy metals are used for ballast in boats, aeroplanes, and motor vehicles; or in balance weights on wheels and crankshafts, gyroscopes, and propellers, and centrifugal clutches, in situations requiring maximum weight in minimum space (for example in watch movements).

In military ordnance, tungsten or uranium is used in armour plating and armour piercing projectiles, as well as in nuclear weapons to increase efficiency (by reflecting neutrons and momentarily delaying the expansion of reacting materials). In the 1970s, tantalum was found to be more effective than copper in shaped charge and explosively formed anti-armour weapons on account of its higher density, allowing greater force concentration, and better deformability. Less-toxic heavy metals, such as copper, tin, tungsten, and bismuth, and probably manganese (as well as boron, a metalloid), have replaced lead and antimony in the green bullets used by some armies and in some recreational shooting munitions. Doubts have been raised about the safety (or green credentials) of tungsten.

Biological and chemical

The biocidal effects of some heavy metals have been known since antiquity. Platinum, osmium, copper, ruthenium, and other heavy metals, including arsenic, are used in anti-cancer treatments, or have shown potential. Antimony (anti-protozoal), bismuth (anti-ulcer), gold (anti-arthritic), and iron (anti-malarial) are also important in medicine. Copper, zinc, silver, gold, or mercury are used in antiseptic formulations; small amounts of some heavy metals are used to control algal growth in, for example, cooling towers. Depending on their intended use as fertilisers or biocides, agrochemicals may contain heavy metals such as chromium, cobalt, nickel, copper, zinc, arsenic, cadmium, mercury, or lead.

Selected heavy metals are used as catalysts in fuel processing (rhenium, for example), synthetic rubber and fibre production (bismuth), emission control devices (palladium and platinum), and in self-cleaning ovens (where cerium(IV) oxide in the walls of such ovens helps oxidise carbon-based cooking residues). In soap chemistry, heavy metals form insoluble soaps that are used in lubricating greases, paint dryers, and fungicides (apart from lithium, the alkali metals and the ammonium ion form soluble soaps).

Colouring and optics

The colours of glass, ceramic glazes, paints, pigments, and plastics are commonly produced by the inclusion of heavy metals (or their compounds) such as chromium, manganese, cobalt, copper, zinc, zirconium, molybdenum, silver, tin, praseodymium, neodymium, erbium, tungsten, iridium, gold, lead, or uranium. Tattoo inks may contain heavy metals, such as chromium, cobalt, nickel, and copper. The high reflectivity of some heavy metals is important in the construction of mirrors, including precision astronomical instruments. Headlight reflectors rely on the excellent reflectivity of a thin film of rhodium.

Electronics, magnets, and lighting

Heavy metals or their compounds can be found in electronic components, electrodes, and wiring and solar panels. Molybdenum powder is used in circuit board inks. Home electrical systems, for the most part, are wired with copper wire for its good conducting properties. Silver and gold are used in electrical and electronic devices, particularly in contact switches, as a result of their high electrical conductivity and capacity to resist or minimise the formation of impurities on their surfaces. Heavy metals have been used in batteries for over 200 years, at least since Volta invented his copper and silver voltaic pile in 1800.

Magnets are often made of heavy metals such as manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, niobium, bismuth, praseodymium, neodymium, gadolinium, and dysprosium. Neodymium magnets are the strongest type of permanent magnet commercially available. They are key components of, for example, car door locks, starter motors, fuel pumps, and power windows.

Heavy metals are used in lighting, lasers, and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Fluorescent lighting relies on mercury vapour for its operation. Ruby lasers generate deep red beams by exciting chromium atoms in aluminum oxide; the lanthanides are also extensively employed in lasers. Copper, iridium, and platinum are used in organic LEDs.

Nuclear

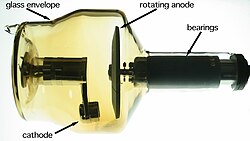

Because denser materials absorb more of certain types of radioactive emissions such as gamma rays than lighter ones, heavy metals are useful for radiation shielding and to focus radiation beams in linear accelerators and radiotherapy applications.

Niche uses of heavy metals with high atomic numbers occur in diagnostic imaging, electron microscopy, and nuclear science. In diagnostic imaging, heavy metals such as cobalt or tungsten make up the anode materials found in x-ray tubes. In electron microscopy, heavy metals such as lead, gold, palladium, platinum, or uranium have been used in the past to make conductive coatings and to introduce electron density into biological specimens by staining, negative staining, or vacuum deposition. In nuclear science, nuclei of heavy metals such as chromium, iron, or zinc are sometimes fired at other heavy metal targets to produce superheavy elements; heavy metals are also employed as spallation targets for the production of neutrons or isotopes of non-primordial elements such as astatine (using lead, bismuth, thorium, or uranium in the latter case).