From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In non-relativistic quantum mechanics, the propagator gives the probability amplitude for a

particle to travel from one spatial point at one time to another spatial point at a later time. It is the

Green's function (

fundamental solution) for the

Schrödinger equation. This means that, if a system has

Hamiltonian H, then the appropriate propagator is a function

satisfying

where

Hx denotes the Hamiltonian written in terms of the

x coordinates,

δ(x) denotes the

Dirac delta-function,

Θ(t) is the

Heaviside step function and

K(x, t ;x′, t′) is the

kernel of the differential operator in question, often referred to as the propagator instead of

G in this context, and henceforth in this article. This propagator can also be written as

where

Û(t, t′) is the

unitary time-evolution operator for the system taking states at time

t′ to states at time

t.

The quantum mechanical propagator may also be found by using a

path integral,

![{\displaystyle K(x,t;x',t')=\int \exp \left[{\frac {i}{\hbar }}\int _{t}^{t'}L({\dot {q}},q,t)\,dt\right]D[q(t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e955342647dcc12817f4053671bf1fce44f81416)

where the boundary conditions of the path integral include

q(t) = x, q(t′) = x′. Here

L denotes the

Lagrangian of the system. The paths that are summed over move only forwards in time, and are integrated with the differential

![{\displaystyle D[q(t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7702e95120aafa87851eca2a469c03b55f54d391)

which follows the path in time.

In non-relativistic

quantum mechanics,

the propagator lets you find the wave function of a system given an

initial wave function and a time interval. The new wave function is

given by the equation

If

K(x,t;x′,t′) only depends on the difference

x − x′, this is a

convolution of the initial wave function and the propagator. This kernel is the kernel of

integral transform.

Basic examples: propagator of free particle and harmonic oscillator

For a time-translationally invariant system, the propagator only depends on the time difference

t − t′, so it may be rewritten as

The

propagator of a one-dimensional free particle, with the far-right expression obtained via

saddle-point methods, is then

|

Similarly, the propagator of a one-dimensional

quantum harmonic oscillator is the

Mehler kernel,

[3][4]

|

The latter may be obtained from the previous free particle result upon making use of van Kortryk's SU(2) Lie-group identity,

-

valid for operators

and

satisfying the Heisenberg relation

![[{\mathsf {x}},{\mathsf {p}}]=i\hbar](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c34a6d2b647663cd1951f44edb2c69556a1c756a)

.

For the

N-dimensional case, the propagator can be simply obtained by the product

Relativistic propagators

In relativistic quantum mechanics and

quantum field theory the propagators are

Lorentz invariant. They give the amplitude for a

particle to travel between two

spacetime points.

Scalar propagator

In quantum field theory, the theory of a free (non-interacting)

scalar field is a useful and simple example which serves to illustrate the concepts needed for more complicated theories. It describes

spin zero particles. There are a number of possible propagators for free scalar field theory. We now describe the most common ones.

Position space

The position space propagators are

Green's functions for the

Klein–Gordon equation. This means they are functions

G(x, y) which satisfy

where:

(As typical in

relativistic quantum field theory calculations, we use units where the

speed of light,

c, and

Planck's reduced constant,

ħ, are set to unity.)

We shall restrict attention to 4-dimensional

Minkowski spacetime. We can perform a

Fourier transform of the equation for the propagator, obtaining

This equation can be inverted in the sense of

distributions noting that the equation

xf(x)=1 has the solution, (see

Sokhotski-Plemelj theorem)

with

ε implying the limit to zero. Below, we discuss the right choice of the sign arising from causality requirements.

The solution is

|

where

is the

4-vector inner product.

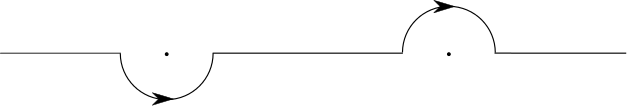

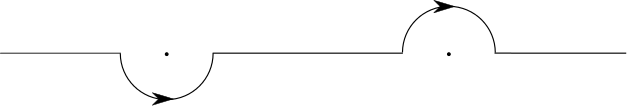

The different choices for how to deform the

integration contour in the above expression lead to various forms for the propagator. The choice of contour is usually phrased in terms of the

integral.

The integrand then has two poles at

so different choices of how to avoid these lead to different propagators.

Causal propagators

Retarded propagator

A contour going clockwise over both poles gives the

causal retarded propagator. This is zero if

x-y is spacelike or if

x ⁰< y ⁰ (i.e. if

y is to the future of

x).

This choice of contour is equivalent to calculating the

limit,

Here

is the

Heaviside step function and

is the

proper time from

x to

y and

is a

Bessel function of the first kind. The expression

means

y causally precedes x which, for Minkowski spacetime, means

and

and

This expression can be related to the

vacuum expectation value of the

commutator of the free scalar field operator,

![{\displaystyle G_{\text{ret}}(x,y)=i\langle 0|\left[\Phi (x),\Phi (y)\right]|0\rangle \Theta (x^{0}-y^{0})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/919d5e45fb1f438f28f4a192a3a521bd875ab1e0)

where

![\left[\Phi (x),\Phi (y)\right]:=\Phi (x)\Phi (y)-\Phi (y)\Phi (x)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dd5c193518649d1efcc53776f9bf57231459b668)

is the

commutator.

Advanced propagator

A contour going anti-clockwise under both poles gives the

causal advanced propagator. This is zero if

x-y is spacelike or if

x ⁰> y ⁰ (i.e. if

y is to the past of

x).

This choice of contour is equivalent to calculating the limit

This expression can also be expressed in terms of the

vacuum expectation value of the

commutator of the free scalar field.

In this case,

![{\displaystyle G_{\text{adv}}(x,y)=-i\langle 0|\left[\Phi (x),\Phi (y)\right]|0\rangle \Theta (y^{0}-x^{0})~.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/52c088b6e64f0a02c16f81454d3e5b1c71956360)

Feynman propagator

A contour going under the left pole and over the right pole gives the

Feynman propagator.

This choice of contour is equivalent to calculating the limit

[5]

Here

where

x and

y are two points in

Minkowski spacetime, and the dot in the exponent is a

four-vector inner product.

H1(2) is a

Hankel function and

K1 is a

modified Bessel function.

This expression can be derived directly from the field theory as the

vacuum expectation value of the

time-ordered product of the free scalar field, that is, the product always taken such that the time ordering of the spacetime points is the same,

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}G_{F}(x-y)&=-i\langle 0|T(\Phi (x)\Phi (y))|0\rangle \\[4pt]&=-i\left\langle 0|\left[\Theta (x^{0}-y^{0})\Phi (x)\Phi (y)+\Theta (y^{0}-x^{0})\Phi (y)\Phi (x)\right]|0\right\rangle .\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/464fd25d8ac399c3cdc9869a3ebb74e23bc6c607)

This expression is

Lorentz invariant, as long as the field operators commute with one another when the points

x and

y are separated by a

spacelike interval.

The usual derivation is to insert a complete set of

single-particle momentum states between the fields with Lorentz

covariant normalization, and to then show that the

Θ functions providing the causal time ordering may be obtained by a

contour integral

along the energy axis, if the integrand is as above (hence the

infinitesimal imaginary part), to move the pole off the real line.

The propagator may also be derived using the

path integral formulation of quantum theory.

Momentum space propagator

The

Fourier transform of the position space propagators can be thought of as propagators in

momentum space. These take a much simpler form than the position space propagators.

They are often written with an explicit

ε term although this is understood to be a reminder about which integration contour is appropriate (see above). This

ε term is included to incorporate boundary conditions and

causality (see below).

For a

4-momentum p the causal and Feynman propagators in momentum space are:

For purposes of Feynman diagram calculations, it is usually convenient to write these with an additional overall factor of

−i (conventions vary).

Faster than light?

The Feynman propagator has some properties that seem baffling at first. In particular, unlike the commutator, the propagator is

nonzero outside of the

light cone,

though it falls off rapidly for spacelike intervals. Interpreted as an

amplitude for particle motion, this translates to the virtual particle

travelling faster than light. It is not immediately obvious how this can

be reconciled with causality: can we use faster-than-light virtual

particles to send faster-than-light messages?

The answer is no: while in

classical mechanics

the intervals along which particles and causal effects can travel are

the same, this is no longer true in quantum field theory, where it is

commutators that determine which operators can affect one another.

So what

does the spacelike part of the propagator represent? In QFT the

vacuum is an active participant, and

particle numbers and field values are related by an

uncertainty principle; field values are uncertain even for particle number

zero. There is a nonzero

probability amplitude to find a significant fluctuation in the vacuum value of the field

Φ(x)

if one measures it locally (or, to be more precise, if one measures an

operator obtained by averaging the field over a small region). Furthermore, the dynamics of the fields tend to favor spatially

correlated fluctuations to some extent. The nonzero time-ordered product

for spacelike-separated fields then just measures the amplitude for a

nonlocal correlation in these vacuum fluctuations, analogous to an

EPR correlation. Indeed, the propagator is often called a

two-point correlation function for the

free field.

Since, by the postulates of quantum field theory, all

observable

operators commute with each other at spacelike separation, messages can

no more be sent through these correlations than they can through any

other EPR correlations; the correlations are in random variables.

Regarding virtual particles, the propagator at spacelike

separation can be thought of as a means of calculating the amplitude for

creating a virtual particle-

antiparticle pair that eventually disappears into the vacuum, or for detecting a virtual pair emerging from the vacuum. In

Feynman's

language, such creation and annihilation processes are equivalent to a

virtual particle wandering backward and forward through time, which can

take it outside of the light cone. However, no signaling back in time

is allowed.

Explanation using limits

This can be made clearer by writing the propagator in the following form for a massless photon,

This is the usual definition but normalised by a factor of

. Then the rule is that one only takes the limit

at the end of a calculation.

One sees that

if

if

and

if

if

Hence this means a single photon will always stay on the light cone.

It is also shown that the total probability for a photon at any time

must be normalised by the reciprocal of the following factor:

We see that the parts outside the light cone usually are zero in the limit and only are important in Feynman diagrams.

Propagators in Feynman diagrams

The most common use of the propagator is in calculating

probability amplitudes for particle interactions using

Feynman diagrams.

These calculations are usually carried out in momentum space. In

general, the amplitude gets a factor of the propagator for every

internal line,

that is, every line that does not represent an incoming or outgoing

particle in the initial or final state. It will also get a factor

proportional to, and similar in form to, an interaction term in the

theory's

Lagrangian for every internal vertex where lines meet. These prescriptions are known as

Feynman rules.

Internal lines correspond to virtual particles. Since the

propagator does not vanish for combinations of energy and momentum

disallowed by the classical equations of motion, we say that the virtual

particles are allowed to be

off shell. In fact, since the propagator is obtained by inverting the wave equation, in general, it will have singularities on the shell.

The energy carried by the particle in the propagator can even be

negative. This can be interpreted simply as the case in which, instead of a particle going one way, its

antiparticle is going the

other

way, and therefore carrying an opposing flow of positive energy. The

propagator encompasses both possibilities. It does mean that one has to

be careful about minus signs for the case of

fermions, whose propagators are not

even functions in the energy and momentum (see below).

Virtual particles conserve energy and momentum. However, since

they can be off the shell, wherever the diagram contains a closed

loop,

the energies and momenta of the virtual particles participating in the

loop will be partly unconstrained, since a change in a quantity for one

particle in the loop can be balanced by an equal and opposite change in

another. Therefore, every loop in a Feynman diagram requires an integral

over a continuum of possible energies and momenta. In general, these

integrals of products of propagators can diverge, a situation that must

be handled by the process of

renormalization.

Other theories

Spin 1⁄2

If the particle possesses

spin

then its propagator is in general somewhat more complicated, as it will

involve the particle's spin or polarization indices. The differential

equation satisfied by the propagator for a spin

1⁄2 particle is given by

[6]

where

I4 is the unit matrix in four dimensions, and employing the

Feynman slash notation. This is the Dirac equation for a delta function source in spacetime. Using the momentum representation,

![{\displaystyle S_{F}(x',x)=\int {\frac {d^{4}p}{(2\pi )^{4}}}\exp {\left[-ip\cdot (x'-x)\right]}{\tilde {S}}_{F}(p),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81a71c7f8b3f04f80e0b46f8ef96cc872982365b)

the equation becomes

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&(i\not \nabla '-m)\int {\frac {d^{4}p}{(2\pi )^{4}}}{\tilde {S}}_{F}(p)\exp {\left[-ip\cdot (x'-x)\right]}\\[6pt]={}&\int {\frac {d^{4}p}{(2\pi )^{4}}}(\not p-m){\tilde {S}}_{F}(p)\exp {\left[-ip\cdot (x'-x)\right]}\\[6pt]={}&\int {\frac {d^{4}p}{(2\pi )^{4}}}I_{4}\exp {\left[-ip\cdot (x'-x)\right]}\\[6pt]={}&I_{4}\delta ^{4}(x'-x),\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4770a7ba0dbc05aa4f9d98e0faa34cb1b94c9a51)

where on the right-hand side an integral representation of the four-dimensional delta function is used. Thus

By multiplying from the left with

(dropping unit matrices from the notation) and using properties of the

gamma matrices,

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\not p\not p&={\frac {1}{2}}(\not p\not p+\not p\not p)\\[6pt]&={\frac {1}{2}}(\gamma _{\mu }p^{\mu }\gamma _{\nu }p^{\nu }+\gamma _{\nu }p^{\nu }\gamma _{\mu }p^{\mu })\\[6pt]&={\frac {1}{2}}(\gamma _{\mu }\gamma _{\nu }+\gamma _{\nu }\gamma _{\mu })p^{\mu }p^{\nu }\\[6pt]&=g_{\mu \nu }p^{\mu }p^{\nu }=p_{\nu }p^{\nu }=p^{2},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/05528a1d6393d467a6668bc427befaffebb1a630)

the momentum-space propagator used in Feynman diagrams for a

Dirac field representing the

electron in

quantum electrodynamics is found to have form

The

iε downstairs is a prescription for how to handle the poles in the complex

p0-plane. It automatically yields the

Feynman contour of integration by shifting the poles appropriately. It is sometimes written

for short. It should be remembered that this expression is just shorthand notation for

(γμpμ − m)−1. "One over matrix" is otherwise nonsensical. In position space one has

This is related to the Feynman propagator by

where

.

Spin 1

The propagator for a

gauge boson in a

gauge theory depends on the choice of convention to fix the gauge. For the gauge used by Feynman and

Stueckelberg, the propagator for a

photon is

The propagator for a massive vector field can be derived from the

Stueckelberg Lagrangian. The general form with gauge parameter

λ reads

With this general form one obtains the propagator in unitary gauge for

λ = 0, the propagator in Feynman or 't Hooft gauge for

λ = 1 and in Landau or Lorenz gauge for

λ = ∞. There are also other notations where the gauge parameter is the inverse of

λ. The name of the propagator, however, refers to its final form and not necessarily to the value of the gauge parameter.

Unitary gauge:

Feynman ('t Hooft) gauge:

Landau (Lorenz) gauge:

Graviton propagator

The graviton propagator for

Minkowski space in

general relativity is

where

is the transverse and traceless

spin-2 projection operator and

is a spin-0 scalar

multiplet.

The graviton propagator for

(Anti) de Sitter space is

where

is the

Hubble constant. Note that upon taking the limit

, the AdS propagator reduces to the Minkowski propagator.

[7]

Related singular functions

The scalar propagators are Green's functions for the Klein–Gordon

equation. There are related singular functions which are important in

quantum field theory. We follow the notation in Bjorken and Drell.

[8] See also Bogolyubov and Shirkov (Appendix A). These functions are most simply defined in terms of the

vacuum expectation value of products of field operators.

Solutions to the Klein–Gordon equation

Pauli–Jordan function

The commutator of two scalar field operators defines the Pauli–Jordan function

by

[8]

![{\displaystyle \langle 0|\left[\Phi (x),\Phi (y)\right]|0\rangle =i\,\Delta (x-y)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ae71b05a978302792aa1c33fff1e4d96f5f2706b)

with

This satisfies

and is zero if

.

Positive and negative frequency parts (cut propagators)

We can define the positive and negative frequency parts of

, sometimes called cut propagators, in a relativistically invariant way.

This allows us to define the positive frequency part:

and the negative frequency part:

These satisfy

[8]

and

Auxiliary function

The anti-commutator of two scalar field operators defines

function by

with

This satisfies

Green's functions for the Klein–Gordon equation

The retarded, advanced and Feynman propagators defined above are all Green's functions for the Klein–Gordon equation.

They are related to the singular functions by

[8]

where

![{\displaystyle D[q(t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7702e95120aafa87851eca2a469c03b55f54d391) which follows the path in time.

which follows the path in time.

and

and  satisfying the Heisenberg relation

satisfying the Heisenberg relation ![[{\mathsf {x}},{\mathsf {p}}]=i\hbar](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c34a6d2b647663cd1951f44edb2c69556a1c756a) .

.

is the d'Alembertian operator acting on the x coordinates.

integral.

integral.

is a Bessel function of the first kind. The expression

is a Bessel function of the first kind. The expression  means y causally precedes x which, for Minkowski spacetime, means

means y causally precedes x which, for Minkowski spacetime, means

and

. Then the rule is that one only takes the limit

. Then the rule is that one only takes the limit  at the end of a calculation.

at the end of a calculation.

if

if

.

.

is the transverse and traceless spin-2 projection operator and

is the transverse and traceless spin-2 projection operator and  is a spin-0 scalar multiplet.

The graviton propagator for (Anti) de Sitter space is

is a spin-0 scalar multiplet.

The graviton propagator for (Anti) de Sitter space is

is the Hubble constant. Note that upon taking the limit

is the Hubble constant. Note that upon taking the limit  , the AdS propagator reduces to the Minkowski propagator.[7]

, the AdS propagator reduces to the Minkowski propagator.[7]

by[8]

by[8]

.

.

, sometimes called cut propagators, in a relativistically invariant way.

, sometimes called cut propagators, in a relativistically invariant way.

function by

function by

![{\displaystyle K(x,t;x',t')=\int \exp \left[{\frac {i}{\hbar }}\int _{t}^{t'}L({\dot {q}},q,t)\,dt\right]D[q(t)]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/e955342647dcc12817f4053671bf1fce44f81416)

![{\displaystyle G_{\text{ret}}(x,y)=i\langle 0|\left[\Phi (x),\Phi (y)\right]|0\rangle \Theta (x^{0}-y^{0})}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/919d5e45fb1f438f28f4a192a3a521bd875ab1e0)

![\left[\Phi (x),\Phi (y)\right]:=\Phi (x)\Phi (y)-\Phi (y)\Phi (x)](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/dd5c193518649d1efcc53776f9bf57231459b668)

![{\displaystyle G_{\text{adv}}(x,y)=-i\langle 0|\left[\Phi (x),\Phi (y)\right]|0\rangle \Theta (y^{0}-x^{0})~.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/52c088b6e64f0a02c16f81454d3e5b1c71956360)

![{\displaystyle S_{F}(x',x)=\int {\frac {d^{4}p}{(2\pi )^{4}}}\exp {\left[-ip\cdot (x'-x)\right]}{\tilde {S}}_{F}(p),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/81a71c7f8b3f04f80e0b46f8ef96cc872982365b)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}&(i\not \nabla '-m)\int {\frac {d^{4}p}{(2\pi )^{4}}}{\tilde {S}}_{F}(p)\exp {\left[-ip\cdot (x'-x)\right]}\\[6pt]={}&\int {\frac {d^{4}p}{(2\pi )^{4}}}(\not p-m){\tilde {S}}_{F}(p)\exp {\left[-ip\cdot (x'-x)\right]}\\[6pt]={}&\int {\frac {d^{4}p}{(2\pi )^{4}}}I_{4}\exp {\left[-ip\cdot (x'-x)\right]}\\[6pt]={}&I_{4}\delta ^{4}(x'-x),\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4770a7ba0dbc05aa4f9d98e0faa34cb1b94c9a51)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}\not p\not p&={\frac {1}{2}}(\not p\not p+\not p\not p)\\[6pt]&={\frac {1}{2}}(\gamma _{\mu }p^{\mu }\gamma _{\nu }p^{\nu }+\gamma _{\nu }p^{\nu }\gamma _{\mu }p^{\mu })\\[6pt]&={\frac {1}{2}}(\gamma _{\mu }\gamma _{\nu }+\gamma _{\nu }\gamma _{\mu })p^{\mu }p^{\nu }\\[6pt]&=g_{\mu \nu }p^{\mu }p^{\nu }=p_{\nu }p^{\nu }=p^{2},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/05528a1d6393d467a6668bc427befaffebb1a630)

![{\displaystyle \langle 0|\left[\Phi (x),\Phi (y)\right]|0\rangle =i\,\Delta (x-y)}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/ae71b05a978302792aa1c33fff1e4d96f5f2706b)