Flag of Scotland

| |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| c. 28 – c. 40 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 20–25 million (Scottish descent) 3,075,137 Scotch-Irish descent) | |

| 4,719,850 | |

| 2,023,474 | |

| 795,000 | |

| Northern Ireland | 760,620 |

| 100,000 | |

| 80,000 | |

| 45,000 | |

| 45,000 | |

| 15,000 | |

| 14,412 | |

| 11,160 (estimate) | |

| 2,403 | |

| 1,459 | |

| Languages | |

| English (Scottish English) Scottish Gaelic Scots | |

| Religion | |

| Presbyterianism, Roman Catholicism, Episcopalianism; other minority groups | |

In modern usage, "Scottish people" or "Scots" is used to refer to anyone whose linguistic, cultural, family ancestral or genetic origins are from Scotland. The Latin word Scoti originally referred to the Gaels, but came to describe all inhabitants of Scotland. Considered archaic or pejorative, the term Scotch has also been used for Scottish people, primarily outside Scotland. John Kenneth Galbraith in his book The Scotch (Toronto: MacMillan, 1964) documents the descendants of 19th-century Scottish pioneers who settled in Southwestern Ontario and affectionately referred to themselves as 'Scotch'. He states the book was meant to give a true picture of life in the community in the early decades of the 20th century.

People of Scottish descent live in many countries other than Scotland. Emigration, influenced by factors such as the Highland and Lowland Clearances, Scottish participation in the British Empire, and latterly industrial decline and unemployment, have resulted in Scottish people being found throughout the world. Scottish emigrants took with them their Scottish languages and culture. Large populations of Scottish people settled the new-world lands of North and South America, Australia and New Zealand. Canada has the highest level of Scottish descendants per capita in the world and the second-largest population of Scottish descendants, after the United States.

Scotland has seen migration and settlement of many peoples at different periods in its history. The Gaels, the Picts and the Britons have their respective origin myths, like most medieval European peoples. Germanic peoples, such as the Anglo-Saxons, arrived beginning in the 7th century, while the Norse settled parts of Scotland from the 8th century onwards. In the High Middle Ages, from the reign of David I of Scotland, there was some emigration from France, England and the Low Countries to Scotland. Some famous Scottish family names, including those bearing the names which became Bruce, Balliol, Murray and Stewart came to Scotland at this time. Today Scotland is one of the countries of the United Kingdom, and the majority of people living there are British citizens.

Ethnic groups of Scotland

Use of the Gaelic language spread throughout nearly the whole of Scotland by the 9th century, reaching a peak in the 11th to 13th centuries, but was never the language of the south-east of the country. King Edgar divided the Kingdom of Northumbria between Scotland and England; at least, most medieval historians now accept the 'gift' by Edgar, in any case, after the later Battle of Carham the Scottish kingdom encompassed many English people, with even more quite possibly arriving after the Norman invasion of England in 1066. South-east of the Firth of Forth, then in Lothian and the Borders (OE: Loðene), a northern variety of Old English, also known as Early Scots, was spoken.

St. Kildans sitting on the village street, 1886

As a result of David I, King of Scots' return from exile in England in 1113, ultimately to assume the throne in 1124 with the help of Norman military force, David invited Norman families from France and England to settle in lands he granted them to spread a ruling class loyal to him. This Davidian Revolution, as many historians call it, brought a European style of feudalism to Scotland along with an influx of people of Norman descent - by invitation, unlike England where it was by conquest. To this day, many of the common family names of Scotland can trace ancestry to Normans from this period, such as the Stewarts, the Bruces, the Hamiltons, the Wallaces, the Melvilles, some Browns and many others.

The Northern Isles and some parts of Caithness were Norn-speaking (the west of Caithness was Gaelic-speaking into the 20th Century, as were some small communities in parts of the Central Highlands). From 1200 to 1500 the Early Scots language spread across the lowland parts of Scotland between Galloway and the Highland line, being used by Barbour in his historical epic The Brus in the late 14th century in Aberdeen.

From 1500 on, Scotland was commonly divided by language into two groups of people, Gaelic-speaking "Highlanders" (the language formerly called Scottis by English speakers and known by many Lowlanders in the 18th century as "Irish") and the Inglis-speaking "Lowlanders" (a language later to be called Scots). Today, immigrants have brought other languages, but almost every adult throughout Scotland is fluent in the English language.

Scottish diaspora

| Number of the Scottish diaspora | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census Year | Population | % of the local population | |||

| 1,792,622 | 8.3 | ||||

| 708,872 | 1.34 | ||||

| 5,460,679 | 1.5 | ||||

| 3,257,161 | 1.1 | ||||

| 4,714,965 | 14.35 | ||||

United States

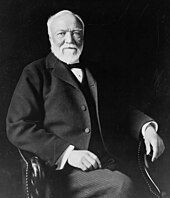

Scottish-born American industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie

In the 2013 American Community Survey 5,310,285 identified as Scottish and 2,976,878 as of Scots-Irish descent. Americans of Scottish descent outnumber the population of Scotland, where 4,459,071 or 88.09% of people identified as ethnic Scottish in the 2001 Census.

The number of Americans of Scottish descent today is estimated to be 20 to 25 million (up to 8.3% of the total US population), and Scotch-Irish, 27 to 30 million (up to 10% of the total US population), the subgroups overlapping and not always distinguishable because of their shared ancestral surnames. The majority of Scotch-Irish originally came from Lowland Scotland and Northern England before migrating to the province of Ulster in Ireland (see Plantation of Ulster) and thence, beginning about five generations later, to North America in large numbers during the eighteenth century.

Canada

As the third-largest ethnic group in Canada and amongst the first Europeans to settle in the country, Scottish people have made a large impact on Canadian culture since colonial times. According to the 2011 Census of Canada, the number of Canadians claiming full or partial Scottish descent is 4,714,970, or 15.10% of the nation's total population.Many respondents may have misunderstood the question and the numerous responses for "Canadian" does not give an accurate figure for numerous groups, particularly those of British Isles origins. Scottish-Canadians are the 3rd biggest ethnic group in Canada. Scottish culture has particularly thrived in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia (Latin for "New Scotland"). There, in Cape Breton, where both lowland and highland Scots settled in large numbers, Canadian Gaelic is still spoken by a small number of residents. Cape Breton is the home of the Gaelic College of Celtic Arts and Crafts. Glengarry County in present-day Eastern Ontario is a historic county that was set up as a settlement for Highland Scots, where many from the Highlands settled to preserve their culture in result of the Highland Clearances. Gaelic was the native language of the community since its settlement in the 18th century although the number of speakers decreased since as a result of English migration. As of the modern 21st century, there are still a few Gaelic speakers in the community.

Australia

The Australian city of Brisbane is named after Scotsman Thomas Brisbane.

By 1830, 15.11% of the colonies' total population were Scots, which increased by the middle of the century to 25,000, or 20-25% of the total population. The Australian Gold Rush of the 1850s provided a further impetus for Scottish migration: in the 1850s 90,000 Scots immigrated to Australia, far more than other British or Irish populations at the time. Literacy rates of the Scottish immigrants ran at 90-95%. By 1860, Scots made up 50% of the ethnic composition of Western Victoria, Adelaide, Penola and Naracoorte. Other settlements in New South Wales included New England, the Hunter Valley and the Illawarra.

Much settlement followed the Highland Potato Famine, Highland Clearances and the Lowland Clearances of the mid-19th century. In the 1840s, Scots-born immigrants constituted 12% of the Australian population. Out of the 1.3 million migrants from Britain to Australia in the period from 1861–1914, 13.5% were Scots. Just 5.3% of the convicts transported to Eastern Australia between 1789 and 1852 were Scots.

A steady rate of Scottish immigration continued into the 20th century and substantial numbers of Scots continued to arrive after 1945. From 1900 until the 1950s, Scots favoured New South Wales, as well as Western Australia and Southern Australia. A strong cultural Scottish presence is evident in the Highland Games, dance, Tartan Day celebrations, clan and Gaelic-speaking societies found throughout modern Australia.

According to the 2011 Australian census, 130,204 Australian residents were born in Scotland, while 1,792,600 claimed Scottish ancestry, either alone or in combination with another ancestry. This is the fourth most commonly nominated ancestry and represents over 8.9% of the total population of Australia.

New Zealand

Scottish Highland family migrating to New Zealand in 1844

Significant numbers of Scottish people also settled in New Zealand. Approximately 20 percent of the original European settler population of New Zealand came from Scotland, and Scottish influence is still visible around the country. The South Island city of Dunedin, in particular, is known for its Scottish heritage and was named as a tribute to Edinburgh by the city's Scottish founders.

Scottish migration to New Zealand dates back to the earliest period of European colonisation, with a large proportion of Pākehā New Zealanders being of Scottish descent. However, identification as "British" or "European" New Zealanders can sometimes obscure their origin. Many Scottish New Zealanders also have Māori or other non-European ancestry.

The majority of Scottish immigrants settled in the South Island. All over New Zealand, the Scots developed different means to bridge the old homeland and the new. Many Caledonian societies were formed, well over 100 by the early twentieth century, who helped maintain Scottish culture and traditions. From the 1860s, these societies organised annual Caledonian Games throughout New Zealand. The Games were sports meets that brought together Scottish settlers and the wider New Zealand public. In so doing, the Games gave Scots a path to cultural integration as Scottish New Zealanders. In the 1961 census there were 47,078 people living in New Zealand who were born in Scotland; in the 2013 census there were 25,953 in this category.

United Kingdom

Carol Ann Duffy, the first woman and the first Scottish person to be appointed the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom

Jackie Kay, Scotland's makar, or national poet

Many people of Scottish descent live in other parts of the United Kingdom. In Ulster particularly the colonial policies of James VI, known as the plantation of Ulster, resulted in a Presbyterian and Scottish society, which formed the Ulster-Scots community. The Protestant Ascendancy did not however benefit them much, as the English espoused the Anglican Church. The number of people of Scottish descent in England and Wales is difficult to quantify due to the many complex migrations on the island, and ancient migration patterns due to wars, famine and conquest. The 2011 Census recorded 708,872 people born in Scotland resident in England, 24,346 resident in Wales and 15,455 resident in Northern Ireland.

Rest of Europe

Other European countries have had their share of Scots immigrants. The Scots have emigrated to mainland Europe for centuries as merchants and soldiers. Many emigrated to France, Poland, Italy, Germany, Scandinavia, and the Netherlands. Recently some scholars suggested that up to 250,000 Russian nationals may have Scottish ancestry.Africa

Guy Scott, the 12th vice-president and acting president of Zambia from Oct 2014 – Jan 2015, is of Scottish descent.

A number of Scottish people settled in South Africa in the 1800s and were known for their road-building expertise, their farming experience, and architectural skills.

Latin America

The largest population of Scots in Latin America is found in Argentina, followed by Chile, Brazil, and Mexico.Scots in mainland Europe

Netherlands

It is said that the first people from the Low Countries to settle in Scotland came in the wake of Maud's marriage to the Scottish king, David I, during the Middle Ages. Craftsmen and tradesmen followed courtiers and in later centuries a brisk trade grew up between the two nations: Scotland's primary goods (wool, hides, salmon and then coal) in exchange for the luxuries obtainable in the Netherlands, one of the major hubs of European trade.By 1600, trading colonies had grown up on either side of the well-travelled shipping routes: the Dutch settled along the eastern seaboard of Scotland; the Scots congregating first in Campvere—where they were allowed to land their goods duty-free and run their own affairs—and then in Rotterdam, where Scottish and Dutch Calvinism coexisted comfortably. Besides the thousands (or, according to one estimate, over 1 million) of local descendants with Scots ancestry, both ports still show signs of these early alliances. Now a museum, 'The Scots House' in the town of Veere was the only place outwith Scotland where Scots Law was practised. In Rotterdam, meanwhile, the doors of the Scots International Church have remained open since 1643.

Russia

Patrick Gordon was a Russian General originally from Scotland and a friend of Peter the Great.

The first Scots to be mentioned in Russia's history were the Scottish soldiers in Muscovy referred to as early as in the 14th century. Among the 'soldiers of fortune' was the ancestor to famous Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov, called George Learmonth. A number of Scots gained wealth and fame in the times of Peter the Great and Catherine the Great. These include Patrick Gordon, Paul Menzies, Samuel Greig, Charles Baird, Charles Cameron, Adam Menelaws and William Hastie. Several doctors to the Russian court were from Scotland, the best known being James Wylie.

The next wave of migration established commercial links with Russia.

The 19th century witnessed the immense literary cross-references between Scotland and Russia.

A Russian scholar, Maria Koroleva, distinguishes between 'the Russian Scots' (properly assimilated) and 'Scots in Russia', who remained thoroughly Scottish.

There are several societies in contemporary Russia to unite the Scots. The Russian census lists does not distinguish Scots from other British people, so it is hard to establish reliable figures for the number of Scots living and working in modern Russia.

Poland

From as far back as the mid-16th century there were Scots trading and settling in Poland. A "Scotch Pedlar's Pack in Poland" became a proverbial expression. It usually consisted of cloths, woollen goods and linen kerchiefs (head coverings). Itinerants also sold tin utensils and ironware such as scissors and knives. Along with the protection offered by King Stephen in the Royal Grant of 1576, a district in Kraków was assigned to Scottish immigrants.Records from 1592 mention Scots settlers granted citizenship of Kraków, and give their employment as trader or merchant. Fees for citizenship ranged from 12 Polish florins to a musket and gunpowder, or an undertaking to marry within a year and a day of acquiring a holding.

By the 17th century, an estimated 30,000 to 40,000 Scots lived in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Many came from Dundee and Aberdeen. Scots could be found in Polish towns on the banks of the Vistula as far south as Kraków. Settlers from Aberdeenshire were mainly Episcopalians or Catholics, but there were also large numbers of Calvinists. As well as Scottish traders, there were also many Scottish soldiers in Poland. In 1656, a number of Scottish highlanders who were disenchanted with Oliver Cromwell's rule went to Poland to join the service of the King of Sweden in his war against it.

The Scots integrated well and many acquired great wealth. They contributed to many charitable institutions in the host country, but did not forget their homeland; for example, in 1701 when collections were made for the restoration fund of the Marischal College, Aberdeen, Scottish settlers in Poland gave generously.

Many royal grants and privileges were granted to Scottish merchants until the 18th century, at which time the settlers began to merge more and more into the native population. "Bonnie Prince Charlie" was half Polish, since he was the son of James Stuart, the "Old Pretender", and Clementina Sobieska, granddaughter of Jan Sobieski, King of Poland. In 1691, the City of Warsaw elected the Scottish immigrant Aleksander Czamer (Alexander Chalmers) as its mayor.

Italy

By 1592, the Scottish community in Rome was big enough to merit the building of Sant'Andrea degli Scozzesi (English: St Andrew of the Scots). It was constructed for the Scottish expatriate community in Rome, especially for those intended for priesthood. The adjoining hospice was a shelter for Catholic Scots who fled their country because of religious persecution. In 1615, Pope Paul V gave the hospice and the nearby Scottish Seminar to the Jesuits. It was rebuilt in 1645. The church and facilities became more important when James Francis Edward Stuart, the Old Pretender, set up residence in Rome in 1717, but were abandoned during the French occupation of Rome in the late 18th century. In 1820, although religious activity was resumed, it was no longer led by the Jesuits. Sant'Andrea degli Scozzesi was reconstructed in 1869 by Luigi Poletti. The church was deconsecrated in 1962 and incorporated into a bank (Cassa di Risparmio delle Province Lombarde). The Scottish Seminar also moved away. The Feast of St Andrew is still celebrated there on 30 November.Gurro in Italy is said to be populated by the descendants of Scottish soldiers. According to local legend, Scottish soldiers fleeing the Battle of Pavia who arrived in the area were stopped by severe blizzards that forced many, if not all, to give up their travels and settle in the town. To this day, the town of Gurro is still proud of its Scottish links. Many of the residents claim that their surnames are Italian translations of Scottish surnames. The town also has a Scottish museum.

Culture

Scottish Gaelic and English are both used on road signs – such as this one in the village of Mallaig – throughout the Highlands and Islands of Scotland

Geographic distribution of speakers of the two native Scottish languages, namely Scots and Scottish Gaelic

Robert Burns, considered by many to be the Scottish national poet

Scottish actor Sean Connery has been polled as "The Greatest Living Scot" and "Scotland's Greatest Living National Treasure".

James Watt, a Scottish mechanical engineer whose improvements in steam engine technology drove the Industrial Revolution.

Language

Historically, Scottish people have spoken many different languages and dialects. The Pictish language, Norse, Norman-French and Brythonic languages have been spoken by forebears of Scottish people. However, none of these are in use today. The remaining three major languages of the Scottish people are English, Scots (various dialects) and Gaelic. Of these three, English is the most common form as a first language. There are some other minority languages of the Scottish people, such as Spanish, used by the population of Scots in Argentina.The Norn language was spoken in the Northern Isles into the early modern period – the current dialects of Shetlandic and Orcadian are heavily influenced by it, to this day.

There is still debate whether Scots is a dialect or a language in its own right, as there is no clear line to define the two. Scots is usually regarded as a midway between the two, as it is highly mutually intelligible with English, particularly the dialects spoken in the North of England as well as those spoken in Scotland, but is treated as a language in some laws.

Scottish English

After the Union of Crowns in 1603, the Scottish Court moved with James VI & I to London and English vocabulary began to be used by the Scottish upper classes. With the introduction of the printing press, spellings became standardised. Scottish English, a Scottish variation of southern English English, began to replace the Scots language. Scottish English soon became the dominant language. By the end of the 17th century, Scots had practically ceased to exist, at least in literary form. While Scots remained a common spoken language, the southern Scottish English dialect was the preferred language for publications from the 18th century to the present day. Today most Scottish people speak Scottish English, which has some distinctive vocabulary and may be influenced to varying degrees by Scots.Scots

Lowland Scots, also known as Lallans or Doric, is a language of Germanic origin. It has its roots in Northern Middle English. After the wars of independence, the English used by Lowland Scots speakers evolved in a different direction from that of Modern English. Since 1424, this language, known to its speakers as Inglis, was used by the Scottish Parliament in its statutes. By the middle of the 15th century, the language's name had changed from Inglis to Scottis. The reformation, from 1560 onwards, saw the beginning of a decline in the use of Scots forms. With the establishment of the Protestant Presbyterian religion, and lacking a Scots translation of the Bible, they used the Geneva Edition. From that point on, God spoke English, not Scots. Scots continued to be used in official legal and court documents throughout the 18th century. However, due to the adoption of the southern standard by officialdom and the Education system the use of written Scots declined. Lowland Scots is still a popular spoken language with over 1.5 million Scots speakers in Scotland. Scots is used by about 30,000 Ulster Scots and is known in official circles as Ullans. In 1993, Ulster Scots was recognised, along with Scots, as a variety of the Scots language by the European Bureau for Lesser-Used Languages.Scottish Gaelic

Scottish Gaelic is a Celtic language with similarities to Irish. Scottish Gaelic comes from Old Irish. It was originally spoken by the Gaels of Dál Riata and the Rhinns of Galloway, later being adopted by the Pictish people of central and eastern Scotland. Gaelic (lingua Scottica, Scottis) became the de facto language of the whole Kingdom of Alba, giving its name to the country (Scotia, "Scotland"). Meanwhile, Gaelic independently spread from Galloway into Dumfriesshire. It is unclear if the Gaelic of 12th-century Clydesdale and Selkirkshire came from Galloway or Scotland-proper. The predominance of Gaelic began to decline in the 13th century, and by the end of the Middle Ages, Scotland was divided into two linguistic zones, the English/Scots-speaking Lowlands and the Gaelic-speaking Highlands and Galloway. Gaelic continued to be spoken widely throughout the Highlands until the 19th century. The Highland clearances actively discouraged the use of Gaelic, caused the numbers of Gaelic speakers to fall. Many Gaelic speakers emigrated to countries such as Canada or moved to the industrial cities of lowland Scotland. Communities where the language is still spoken natively are restricted to the west coast of Scotland; and especially the Hebrides. However, large proportions of Gaelic speakers also live in the cities of Glasgow and Edinburgh in Scotland. A report in 2005 by the Registrar General for Scotland based on the 2001 UK Census showed about 92,400 people or 1.9% of the population can speak Gaelic while the number of people able to read and write rose by 7.5% and 10% respectively. Outwith Scotland, there are communities of Scottish Gaelic speakers such as the Canadian Gaelic community; though their numbers have also been declining rapidly. Gaelic language is recognised as a minority Language by the European Union. The Scottish parliament is also seeking to increase the use of Gaelic in Scotland through the Gaelic Language (Scotland) Act 2005. Gaelic is now used as a first language in some schools and is prominently seen in use on dual language road signs throughout the Gaelic speaking parts of Scotland. It is recognised as an official language of Scotland with "equal respect" to English.Religion

The modern people of Scotland remain a mix of different religions and no religion. Christianity is the largest faith in Scotland. In the 2011 census, 53.8% of the Scottish population identified as Christian. The Protestant and Catholic divisions still remain in the society. In Scotland the main Protestant body is the Church of Scotland which is Presbyterian. The high kirk for Presbyterians is St Giles' Cathedral. In the United States, people of Scottish and Scots-Irish descent are chiefly Protestant, with many belonging to the Baptist or Methodist churches, or various Presbyterian denominations. According to the Social Scottish Attitudes research, 52% of Scottish people identified as having no religion in 2016. As a result, Scotland has thus become a secular and majority non-religious country, unique to the other UK countries.Science and engineering

Alexander Fleming. His discovery of penicillin had changed the world of modern medicine by introducing the age of antibiotics.

Sport

Massed pipebands at the Glengarry Highland Games, Ontario, Canada

The modern games of curling and golf originated in Scotland. Both sports are governed by bodies headquartered in Scotland, the World Curling Federation and the Royal and Ancient Golf Club of St Andrews respectively. Scots helped to popularise and spread the sport of association football; the first official international match was played in Glasgow between Scotland and England in 1872.

Clans

Map of Scottish highland clans and lowland families.

Campbell of Argyle. A romanticised Victorian-era illustration of a Clansman by R. R. McIan from The Clans of the Scottish Highlands published in 1845.

Anglicisation

Many Scottish surnames have become anglicised over the centuries. This reflected the gradual spread of English, also known as Early Scots, from around the 13th century onwards, through Scotland beyond its traditional area in the Lothians. It also reflected some deliberate political attempts to promote the English language in the outlying regions of Scotland, including following the Union of the Crowns under King James VI of Scotland and I of England in 1603, and then the Acts of Union of 1707 and the subsequent defeat of rebellions.However, many Scottish surnames have remained predominantly Gaelic albeit written according to English orthographic practice (as with Irish surnames). Thus MacAoidh in Gaelic is Mackay in English, and MacGill-Eain in Gaelic is MacLean and so on. Mac (sometimes Mc) is common as, effectively, it means "son of". MacDonald, MacAulay, Gilmore, Gilmour, MacKinley, Macintosh, MacKenzie, MacNeill, MacPherson, MacLear, MacAra, Craig, Lauder, Menzies, Galloway and Duncan are just a few of many examples of traditional Scottish surnames. There are, of course, also the many surnames, like Wallace and Morton, stemming from parts of Scotland which were settled by peoples other than the (Gaelic) Scots. The most common surnames in Scotland are Smith and Brown, which come from several origins each – e.g. Smith can be a translation of Mac a' Ghobhainn (thence also e.g. MacGowan), and Brown can refer to the colour, or be akin to MacBrayne.

Anglicisation is not restricted to language. In his Socialism: critical and constructive, published in 1921, future British Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald wrote: "The Anglification of Scotland has been proceeding apace to the damage of its education, its music, its literature, its genius, and the generation that is growing up under this influence is uprooted from its past, and, being deprived of the inspiration of its nationality, is also deprived of its communal sense."

Etymology

Originally the Romans used Scotia to refer to the Gaels living in Ireland. The Venerable Bede (c. 672 or 673 – 27 May, 735) uses the word Scottorum for the nation from Ireland who settled part of the Pictish lands: "Scottorum nationem in Pictorum parte recipit." This we can infer to mean the arrival of the people, also known as the Gaels, in the Kingdom of Dál Riata, in the western edge of Scotland. It is of note that Bede used the word natio (nation) for the Scots, where he often refers to other peoples, such as the Picts, with the word gens (race). In the 10th-century Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the word Scot is mentioned as a reference to the "Land of the Gaels". The word Scottorum was again used by an Irish king in 1005: Imperator Scottorum was the title given to Brian Bóruma by his notary, Mael Suthain, in the Book of Armagh. This style was subsequently copied by the Scottish kings. Basileus Scottorum appears on the great seal of King Edgar (1074–1107). Alexander I (c. 1078–1124) used the words Rex Scottorum on his great seal, as did many of his successors up to and including James VI.In modern times the words Scot and Scottish are applied mainly to inhabitants of Scotland. The possible ancient Irish connotations are largely forgotten. The language known as Ulster Scots, spoken in parts of northeastern Ireland, is the result of 17th and 18th century immigration to Ireland from Scotland.

In the English language, the word Scotch is a term to describe a thing from Scotland, such as Scotch whisky. However, when referring to people, the preferred term is Scots. Many Scottish people find the term Scotch to be offensive when applied to people. The Oxford Dictionary describes Scotch as an old-fashioned term for "Scottish".