From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Cancer immunotherapy |

|---|

|

Cancer immunotherapy (sometimes called

immuno-oncology) is the artificial stimulation of the

immune system to treat

cancer, improving on the system's natural ability to fight cancer. It is an application of the

fundamental research of

cancer immunology and a growing subspecialty of

oncology. It exploits the fact that

cancer cells often have

tumor antigens, molecules on their surface that can be detected by the

antibody proteins of the immune system, binding to them. The tumor

antigens are often

proteins or other macromolecules (e.g.

carbohydrates).

Normal antibodies bind to external pathogens, but the modified

immunotherapy antibodies bind to the tumor antigens marking and

identifying the cancer cells for the immune system to inhibit or kill.

Immunotherapy categories

A wide range of cancers can be treated by various immunotherapy

medicines that have been approved in many jurisdictions around the

world.

Cellular immunotherapy

Dendritic cell therapy

Blood

cells are removed from the body, incubated with tumour antigen(s) and

activated. Mature dendritic cells are then returned to the original

cancer-bearing donor to induce an immune response.

Dendritic cell therapy provokes anti-tumor responses by causing

dendritic cells to present tumor antigens to lymphocytes, which

activates them, priming them to kill other cells that present the

antigen. Dendritic cells are antigen presenting cells (APCs) in the

mammalian immune system. In cancer treatment they aid cancer antigen targeting. The only approved cellular cancer therapy based on dendritic cells is

sipuleucel-T.

One method of inducing dendritic cells to present tumor antigens is by vaccination with autologous tumor lysates

or short peptides (small parts of protein that correspond to the

protein antigens on cancer cells). These peptides are often given in

combination with

adjuvants (highly

immunogenic

substances) to increase the immune and anti-tumor responses. Other

adjuvants include proteins or other chemicals that attract and/or

activate dendritic cells, such as

granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF).

Dendritic cells can also be activated

in vivo

by making tumor cells express GM-CSF. This can be achieved by either

genetically engineering tumor cells to produce GM-CSF or by infecting

tumor cells with an

oncolytic virus that expresses GM-CSF.

Another strategy is to remove dendritic cells from the blood of a

patient and activate them outside the body. The dendritic cells are

activated in the presence of tumor antigens, which may be a single

tumor-specific peptide/protein or a tumor

cell lysate (a solution of broken down tumor cells). These cells (with optional adjuvants) are infused and provoke an immune response.

Dendritic cell therapies include the use of antibodies that bind

to receptors on the surface of dendritic cells. Antigens can be added to

the antibody and can induce the dendritic cells to mature and provide

immunity to the tumor. Dendritic cell receptors such as

TLR3,

TLR7,

TLR8 or

CD40 have been used as antibody targets.

Dendritic cell-NK cell interface also has an important role in

immunotherapy. The design of new dendritic cell-based vaccination

strategies should also encompass NK cell-stimulating potency. It is

critical to systematically incorporate NK cells monitoring as an outcome

in antitumor DC-based clinical trials.

Approved drugs

CAR-T cell therapy

The premise of CAR-T immunotherapy is to modify T cells to recognize

cancer cells in order to more effectively target and destroy them.

Scientists harvest T cells from people, genetically alter them to add a

chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) that specifically recognizes cancer

cells, then infuse the resulting CAR-T cells into patients to attack

their tumors.

Approved drugs

Antibody therapy

Many forms of antibodies can be engineered.

Antibodies are a key component of the

adaptive immune response,

playing a central role in both recognizing foreign antigens and

stimulating an immune response. Antibodies are Y-shaped proteins

produced by some

B cells and are composed of two regions: an

antigen-binding fragment (Fab), which binds to antigens, and a

Fragment crystallizable (Fc) region, which interacts with so-called

Fc receptors that are expressed on the surface of different immune cell types including

macrophages,

neutrophils and NK cells. Many immunotherapeutic regimens involve antibodies.

Monoclonal antibody

technology engineers and generates antibodies against specific

antigens, such as those present on tumor surfaces. These antibodies that

are specific to the antigens of the tumor, can then be injected into a

tumor

Antibody types

Conjugation

Two types are used in cancer treatments:

- Naked monoclonal antibodies are antibodies without added elements. Most antibody therapies use this antibody type.

- Conjugated monoclonal antibodies are joined to another molecule, which is either cytotoxic or radioactive. The toxic chemicals are those typically used as chemotherapy

drugs, but other toxins can be used. The antibody binds to specific

antigens on cancer cell surfaces, directing the therapy to the tumor.

Radioactive compound-linked antibodies are referred to as radiolabelled.

Chemolabelled or immunotoxins antibodies are tagged with

chemotherapeutic molecules or toxins, respectively.

Fc regions

Fc's ability to bind

Fc receptors

is important because it allows antibodies to activate the immune

system. Fc regions are varied: they exist in numerous subtypes and can

be further modified, for example with the addition of sugars in a

process called

glycosylation. Changes in the

Fc region

can alter an antibody's ability to engage Fc receptors and, by

extension, will determine the type of immune response that the antibody

triggers. Many cancer immunotherapy drugs, including

PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors, are antibodies. For example,

immune checkpoint blockers targeting PD-1 are antibodies designed to bind PD-1 expressed by T cells and reactivate these cells to eliminate

tumors.

Anti-PD-1 drugs

contain not only an Fab region that binds PD-1 but also an Fc region.

Experimental work indicates that the Fc portion of cancer immunotherapy

drugs can affect the outcome of treatment. For example, anti-PD-1 drugs

with Fc regions that bind inhibitory Fc receptors can have decreased

therapeutic efficacy.

Imaging studies have further shown that the Fc region of anti-PD-1

drugs can bind Fc receptors expressed by tumor-associated macrophages.

This process removes the drugs from their intended targets (i.e. PD-1

molecules expressed on the surface of T cells) and limits therapeutic

efficacy. Furthermore, antibodies targeting the co-stimulatory protein

CD40 require engagement with selective Fc receptors for optimal therapeutic efficacy. Together, these studies underscore the importance of Fc status in antibody-based

immune checkpoint targeting strategies.

Human/non-human balance

Antibodies

are also referred to as murine, chimeric, humanized and human. Murine

antibodies are from a different species and carry a risk of immune

reaction. Chimeric antibodies attempt to reduce murine antibodies'

immunogenicity

by replacing part of the antibody with the corresponding human

counterpart, known as the constant region. Humanized antibodies are

almost completely human; only the

complementarity determining regions of the

variable regions are derived from murine sources. Human antibodies have been produced using unmodified human DNA.

Antibody-dependent

cell-mediated cytotoxicity. When the Fc receptors on natural killer

(NK) cells interact with Fc regions of antibodies bound to cancer cells,

the NK cell releases perforin and granzyme, leading to cancer cell

apoptosis.

Cell death mechanisms

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC)

Antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity

(ADCC) requires antibodies to bind to target cell surfaces. Antibodies

are formed of a binding region (Fab) and the Fc region that can be

detected by immune system cells via their

Fc surface receptors.

Fc receptors are found on many immune system cells, including NK cells.

When NK cells encounter antibody-coated cells, the latter's Fc regions

interact with their Fc receptors, releasing

perforin and

granzyme B to kill the tumor cell. Examples include

Rituximab,

Ofatumumab

and Alemtuzumab. Antibodies under development have altered Fc regions

that have higher affinity for a specific type of Fc receptor, FcγRIIIA,

which can dramatically increase effectiveness.

Complement

The

complement system includes blood proteins that can cause cell death after an antibody binds to the cell surface (the

classical complement pathway,

among the ways of complement activation). Generally the system deals

with foreign pathogens, but can be activated with therapeutic antibodies

in cancer. The system can be triggered if the antibody is chimeric,

humanized or human; as long as it contains the

IgG1 Fc region. Complement can lead to cell death by activation of the

membrane attack complex, known as complement-dependent

cytotoxicity; enhancement of

antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity;

and CR3-dependent cellular cytotoxicity. Complement-dependent

cytotoxicity occurs when antibodies bind to the cancer cell surface, the

C1 complex binds to these antibodies and subsequently protein pores are

formed in the cancer

cell membrane.

FDA-approved antibodies

Alemtuzumab

Atezolizumab

Durvalumab

(Imfinzi) is a human immunoglobulin G1 kappa (IgG1κ) monoclonal

antibody that blocks the interaction of programmed cell death ligand 1

(PD-L1) with the PD-1 and CD80 (B7.1) molecules. Durvalumab is approved

for the treatment of patients with locally advanced or metastatic

urothelial carcinoma who:

- have disease progression during or following platinum-containing chemotherapy.

- have disease progression within 12 months of neoadjuvant or adjuvant treatment with platinum-containing chemotherapy.

Ipilimumab

Ipilimumab (Yervoy) is a human

IgG1 antibody that binds the surface protein

CTLA4. In normal physiology T-cells are activated by two signals: the

T-cell receptor binding to an

antigen-

MHC complex and T-cell surface receptor CD28 binding to

CD80 or

CD86

proteins. CTLA4 binds to CD80 or CD86, preventing the binding of CD28

to these surface proteins and therefore negatively regulates the

activation of T-cells.

Active

cytotoxic T-cells

are required for the immune system to attack melanoma cells. Normally

inhibited active melanoma-specific cytotoxic T-cells can produce an

effective anti-tumor response. Ipilumumab can cause a shift in the ratio

of

regulatory T-cells

to cytotoxic T-cells to increase the anti-tumor response. Regulatory

T-cells inhibit other T-cells, which may benefit the tumor.

Ofatumumab

Ofatumumab is a second generation human

IgG1 antibody that binds to

CD20. It is used in the treatment of

chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) because the cancerous cells of CLL are usually CD20-expressing B-cells. Unlike

rituximab,

which binds to a large loop of the CD20 protein, ofatumumab binds to a

separate, small loop. This may explain their different characteristics.

Compared to rituximab, ofatumumab induces complement-dependent

cytotoxicity at a lower dose with less

immunogenicity.

Pembrolizumab

Rituximab

Rituximab is a chimeric monoclonal IgG1 antibody specific for CD20, developed from its parent antibody

Ibritumomab.

As with ibritumomab, rituximab targets CD20, making it effective in

treating certain B-cell malignancies. These include aggressive and

indolent lymphomas such as

diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma and

leukemias such as B-cell

chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Although the function of CD20 is relatively unknown, CD20 may be a

calcium channel involved in B-cell activation. The antibody's mode of action is primarily through the induction of ADCC and

complement-mediated cytotoxicity. Other mechanisms include apoptosis and cellular growth arrest. Rituximab also increases the sensitivity of cancerous B-cells to chemotherapy.

Cytokine therapy

Cytokines

are proteins produced by many types of cells present within a tumor.

They can modulate immune responses. The tumor often employs them to

allow it to grow and reduce the immune response. These immune-modulating

effects allow them to be used as drugs to provoke an immune response.

Two commonly used cytokines are interferons and interleukins.

Interferon

Interferons

are produced by the immune system. They are usually involved in

anti-viral response, but also have use for cancer. They fall in three

groups:

type I (IFNα and IFNβ),

type II (IFNγ) and

type III (IFNλ). IFNα has been approved for use in

hairy-cell leukaemia, AIDS-related Kaposi's sarcoma, follicular lymphoma,

chronic myeloid leukaemia

and melanoma. Type I and II IFNs have been researched extensively and

although both types promote anti-tumor immune system effects, only type I

IFNs have been shown to be clinically effective. IFNλ shows promise for

its anti-tumor effects in

animal models.

Unlike type I IFNs,

Interferon gamma is not approved yet for the treatment of any cancer.However, improved survival was observed when

Interferon gamma was administrated to patients with

bladder carcinoma and

melanoma cancers. The most promising result was achieved in patients with stage 2 and 3 of

ovarian carcinoma.The

in vitro

study of IFN-gamma in cancer cells is more extensive and results

indicate anti-proliferative activity of IFN-gamma leading to the growth

inhibition or cell death, generally induced by

apoptosis but sometimes by

autophagy.

Interleukin

Combination immunotherapy

Combining various immunotherapies such as PD1 and CTLA4 inhibitors can enhance anti-tumor response leading to durable responses.

Combining checkpoint immunotherapies with pharmaceutical agents

has the potential to improve response, and such combination therapies

are a highly investigated area of clinical investigation. Immunostimulatory drugs such as

CSF-1R inhibitors and

TLR agonists have been particularly effective in this setting.

Polysaccharide-K

Genetic pre-testing for therapeutic significance

Because

of the high cost of many of the immunotherapy medications and the

reluctance of medical insurance companies to prepay for their

prescriptions various test methods have been proposed, to attempt to

forecast the effectiveness of these medications. The detection of

PD-L1

protein seemed to be an indication of cancer susceptible to several

immunotherapy medications, but research found that both the lack of this

protein or its inclusion in the cancerous tissue was inconclusive, due

to the little-understood varying quantities of the protein during

different times and locations within the infected cells and tissue.

In

2018 some genetic indications such as

Tumor Mutational Burden (TMB, the number of mutations within a targeted genetic region in the cancerous cell's DNA), and

Microsatellite instability

(MSI, the quantity of impaired DNA mismatch leading to probable

mutations), have been approved by the FDA as good indicators for the

probability of effective treatment of immunotherapy medication for

certain cancers, but research is still in progress.

In some cases the FDA has approved genetic tests for medication

that is specific to certain genetic markers. For example, the FDA

approved

BRAF associated medication for metastatic melanoma, to be administered to patients after testing for the BRAF genetic mutation.

Tests of this sort are being widely advertised for general cancer

treatment and are expensive. In the past, some genetic testing for

cancer treatment has been involved in scams such as the Duke University

Cancer Fraud scandal, or claimed to be hoaxes.

Research

Adoptive T-cell therapy

Cancer

specific T-cells can be obtained by fragmentation and isolation of

tumour infiltrating lymphocytes, or by genetically engineering cells

from peripheral blood. The cells are activated and grown prior to

transfusion into the recipient (tumor bearer).

Adoptive T cell therapy is a form of

passive immunization by the transfusion of T-cells (

adoptive cell transfer). They are found in

blood and tissue and usually activate when they find foreign

pathogens.

Specifically they activate when the T-cell's surface receptors

encounter cells that display parts of foreign proteins on their surface

antigens. These can be either infected cells, or

antigen presenting cells (APCs). They are found in normal tissue and in tumor tissue, where they are known as

tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). They are activated by the presence of APCs such as dendritic cells that present

tumor antigens.

Although these cells can attack the tumor, the environment within the

tumor is highly immunosuppressive, preventing immune-mediated tumour

death.

Multiple ways of producing and obtaining tumour targeted T-cells

have been developed. T-cells specific to a tumor antigen can be removed

from a tumor sample (TILs) or filtered from blood. Subsequent activation

and culturing is performed ex vivo, with the results reinfused. Activation can take place through gene therapy, or by exposing the T cells to tumor antigens.

As of 2014, multiple ACT clinical trials were underway.

Importantly, one study from 2018 showed that clinical responses can be

obtained in patients with metastatic melanoma resistant to multiple

previous immunotherapies.

Another approach is adoptive transfer of haploidentical

γδ T cells or

NK cells from a healthy donor. The major advantage of this approach is that these cells do not cause

GVHD. The disadvantage is frequently impaired function of the transferred cells.

Anti-CD47 therapy

Many tumor cells overexpress

CD47 to escape

immunosurveilance of host immune system. CD47 binds to its receptor

signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) and downregulate

phagocytosis of tumor cell.

Therefore, anti-CD47 therapy aims to restore clearance of tumor cells.

Additionally, growing evidence supports the employment of tumor

antigen-specific

T cell response in response to anti-CD47 therapy. A number of therapeutics is being developed, including anti-CD47

antibodies, engineered

decoy receptors, anti-SIRPα

antibodies and bispecific agents. As of 2017, wide range of solid and hematologic malignancies were being clinically tested.

Anti-GD2 antibodies

Carbohydrate antigens on the surface of cells can be used as targets for immunotherapy.

GD2 is a

ganglioside found on the surface of many types of cancer cell including

neuroblastoma,

retinoblastoma,

melanoma,

small cell lung cancer,

brain tumors,

osteosarcoma,

rhabdomyosarcoma,

Ewing’s sarcoma,

liposarcoma,

fibrosarcoma,

leiomyosarcoma and other

soft tissue sarcomas.

It is not usually expressed on the surface of normal tissues, making it

a good target for immunotherapy. As of 2014, clinical trials were

underway.

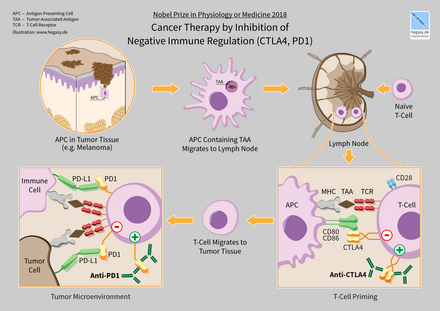

Immune checkpoints

Cancer therapy by inhibition of negative immune regulation (CTLA4, PD1)

Immune checkpoints

affect immune system function. Immune checkpoints can be stimulatory or

inhibitory. Tumors can use these checkpoints to protect themselves from

immune system attacks. Currently approved checkpoint therapies block

inhibitory checkpoint receptors. Blockade of negative feedback signaling

to immune cells thus results in an enhanced immune response against

tumors.

One ligand-receptor interaction under investigation is the interaction between the transmembrane

programmed cell death 1 protein (PDCD1, PD-1; also known as CD279) and its ligand,

PD-1 ligand 1

(PD-L1, CD274). PD-L1 on the cell surface binds to PD1 on an immune

cell surface, which inhibits immune cell activity. Among PD-L1 functions

is a key regulatory role on T cell activities. It appears that

(cancer-mediated) upregulation of PD-L1 on the cell surface may inhibit T

cells that might otherwise attack. PD-L1 on cancer cells also inhibits

FAS- and interferon-dependent apoptosis, protecting cells from cytotoxic

molecules produced by T cells. Antibodies that bind to either PD-1 or

PD-L1 and therefore block the interaction may allow the T-cells to

attack the tumor.

CTLA-4 blockade

The first checkpoint antibody approved by the FDA was ipilimumab, approved in 2011 for treatment of melanoma. It blocks the immune checkpoint molecule

CTLA-4.

Clinical trials have also shown some benefits of anti-CTLA-4 therapy on

lung cancer or pancreatic cancer, specifically in combination with

other drugs. In on-going trials the combination of CTLA-4 blockade with PD-1 or

PD-L1 inhibitors is tested on different types of cancer.

However, patients treated with check-point blockade (specifically

CTLA-4 blocking antibodies), or a combination of check-point blocking

antibodies, are at high risk of suffering from immune-related adverse

events such as dermatologic, gastrointestinal, endocrine, or hepatic

autoimmune reactions.

These are most likely due to the breadth of the induced T-cell

activation when anti-CTLA-4 antibodies are administered by injection in

the blood stream.

Using a mouse model of bladder cancer, researchers have found

that a local injection of a low dose anti-CTLA-4 in the tumour area had

the same tumour inhibiting capacity as when the antibody was delivered

in the blood.

At the same time the levels of circulating antibodies were lower,

suggesting that local administration of the anti-CTLA-4 therapy might

result in fewer adverse events.

PD-1 inhibitors

Initial clinical trial results with IgG4 PD1 antibody

Nivolumab were published in 2010.

It was approved in 2014. Nivolumab is approved to treat melanoma, lung

cancer, kidney cancer, bladder cancer, head and neck cancer, and

Hodgkin's lymphoma.

A 2016 clinical trial for non-small cell lung cancer failed to meet its

primary endpoint for treatment in the first line setting, but is FDA

approved in subsequent lines of therapy.

Pembrolizumab is another PD1 inhibitor that was approved by the FDA in 2014.

Keytruda (

Pembrolizumab) is approved to treat melanoma and lung cancer.

Antibody

BGB-A317 is a PD-1 inhibitor (designed to not bind Fc gamma receptor I) in early clinical trials.

PD-L1 inhibitors

In May 2016, PD-L1 inhibitor

atezolizumab was approved for treating bladder cancer.

Other

Other modes of enhancing [adoptive] immuno-therapy include targeting so-called

intrinsic checkpoint blockades e.g.

CISH.

A number of cancer patients do not respond to immune checkpoint

blockade. Response rate may be improved by combining immune checkpoint

blockade with additional rationally selected anticancer therapies (out

of which some may stimulate T cell infiltration into tumors). For

example, targeted therapies such, radiotherapy, vasculature targeting

agents, and immunogenic chemotherapy can improve immune checkpoint blockade response in animal models of cancer.

Oncolytic virus

An

oncolytic virus is a virus that preferentially infects and kills cancer cells. As the infected cancer cells are destroyed by

oncolysis,

they release new infectious virus particles or virions to help destroy

the remaining tumour. Oncolytic viruses are thought not only to cause

direct destruction of the tumour cells, but also to stimulate host

anti-tumour immune responses for long-term immunotherapy.

The potential of viruses as anti-cancer agents was first realized

in the early twentieth century, although coordinated research efforts

did not begin until the 1960s. A number of viruses including adenovirus,

reovirus, measles, herpes simplex, Newcastle disease virus and vaccinia

have now been clinically tested as oncolytic agents. T-Vec is the first

FDA-approved

oncolytic virus for the treatment of melanoma. A number of other oncolytic viruses are in Phase II-III development.

Polysaccharides

Neoantigens

Many

tumors express mutations. These mutations potentially create new

targetable antigens (neoantigens) for use in T cell immunotherapy. The

presence of CD8+ T cells in cancer lesions, as identified using RNA

sequencing data, is higher in tumors with a high

mutational burden.

The level of transcripts associated with cytolytic activity of natural

killer cells and T cells positively correlates with mutational load in

many human tumors. In non–small cell lung cancer patients treated with

lambrolizumab, mutational load shows a strong correlation with clinical

response. In melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab, long-term

benefit is also associated with a higher mutational load, although less

significantly. The predicted MHC binding neoantigens in patients with a

long-term clinical benefit were enriched for a series of

tetrapeptide motifs that were not found in tumors of patients with no or minimal clinical benefit. However, human neoantigens identified in other studies do not show the bias toward tetrapeptide signatures.