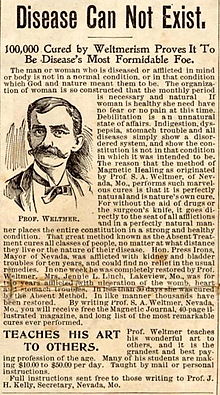

"Disease Can Not Exist", October 1899 advertisement in the People's Home Journal for Weltmerism, a form of "magnetic healing"

The history of alternative medicine refers to the history of a group of diverse medical practices that were collectively promoted as "alternative medicine"

beginning in the 1970s, to the collection of individual histories of

members of that group, or to the history of western medical practices

that were labeled "irregular practices" by the western medical

establishment. It includes the histories of complementary medicine and of integrative medicine.

"Alternative medicine" is a loosely defined and very diverse set of

products, practices, and theories that are perceived by its users to

have the healing effects of medicine, but do not originate from evidence gathered using the scientific method, are not part of biomedicine, or are contradicted by scientific evidence or established science. "Biomedicine" is that part of medical science that applies principles of anatomy, physics, chemistry, biology, physiology, and other natural sciences to clinical practice, using scientific methods to establish the effectiveness of that practice.

Much of what is now categorized as alternative medicine was

developed as independent, complete medical systems, was developed long

before biomedicine and use of scientific methods, and was developed in

relatively isolated regions of the world where there was little or no

medical contact with pre-scientific western medicine, or with each

other's systems. Examples are Traditional Chinese medicine and the Ayurvedic medicine of India. Other alternative medicine practices, such as homeopathy,

were developed in western Europe and in opposition to western medicine,

at a time when western medicine was based on unscientific theories that

were dogmatically imposed by western religious authorities. Homeopathy

was developed prior to discovery of the basic principles of chemistry,

which proved homeopathic remedies contained nothing but water. But

homeopathy, with its remedies made of water, was harmless compared to

the unscientific and dangerous orthodox western medicine practiced at

that time, which included use of toxins and draining of blood, often resulting in permanent disfigurement or death. Other alternative practices such as chiropractic and osteopathic manipulative medicine,

were developed in the United States at a time that western medicine was

beginning to incorporate scientific methods and theories, but the

biomedical model was not yet totally dominant. Practices such as

chiropractic and osteopathic, each considered to be irregular by the

medical establishment, also opposed each other, both rhetorically and

politically with licensing legislation. Osteopathic practitioners added

the courses and training of biomedicine to their licensing, and licensed

Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine holders began diminishing use of the

unscientific origins of the field, and without the original practices

and theories, is now considered the same as biomedicine.

Until the 1970s, western practitioners that were not part of the

medical establishment were referred to "irregular practitioners", and

were dismissed by the medical establishment as unscientific or quackery. Irregular practice became increasingly marginalized as quackery

and fraud, as western medicine increasingly incorporated scientific

methods and discoveries, and had a corresponding increase in success of

its treatments. In the 1970s, irregular practices were grouped with

traditional practices of nonwestern cultures and with other unproven or

disproven practices that were not part of biomedicine, with the group

promoted as being "alternative medicine". Following the counterculture movement

of the 1960s, misleading marketing campaigns promoting "alternative

medicine" as being an effective "alternative" to biomedicine, and with

changing social attitudes about not using chemicals, challenging the

establishment and authority of any kind, sensitivity to giving equal

measure to values and beliefs of other cultures and their practices

through cultural relativism, adding postmodernism and deconstructivism

to ways of thinking about science and its deficiencies, and with

growing frustration and desperation by patients about limitations and

side effects of science-based medicine,

use of alternative medicine in the west began to rise, then had

explosive growth beginning in the 1990s, when senior level political

figures began promoting alternative medicine, and began diverting

government medical research funds into research of alternative,

complementary, and integrative medicine.

Alternative medicine

The concept of alternative medicine is problematic as it cannot exist

autonomously as an object of study in its own right but must always be

defined in relation to a non-static and transient medical orthodoxy. It also divides medicine into two realms, a medical mainstream and fringe, which, in privileging orthodoxy,

presents difficulties in constructing an historical analysis

independent of the often biased and polemical views of regular medical

practitioners.

The description of non-conventional medicine as alternative reinforces

both its marginality and the centrality of official medicine. Although more neutral than either pejorative or promotional designations such as “quackery” or “natural medicine”, cognate terms like “unconventional”, “heterodox”, “unofficial”, “irregular”, "folk", "popular", "marginal", “complementary”, “integrative” or “unorthodox” define their object against the standard of conventional biomedicine, entail particular perspectives and judgements, often carry moral overtones, and can be inaccurate.

Conventional medical practitioners in the West have, since the

nineteenth century, used some of these and similar terms as a means of

defining the boundary of "legitimate" medicine, marking the division between that which is scientific and that which is not. The definition of mainstream medicine, generally understood to refer to a system of licensed medicine which enjoys state and legal protection in a jurisdiction, is also highly specific to time and place. In countries such as India and China traditional systems of medicine, in conjunction with Western biomedical science, may be considered conventional and mainstream. The shifting nature of these terms is underlined by recent efforts to demarcate between alternative treatments on the basis of efficacy

and safety and to amalgamate those therapies with scientifically

adjudged value into complementary medicine as a pluralistic adjunct to

conventional practice. This would introduce a new line of division based upon medical validity.

Before the "fringe"

"Marriage à la Mode, Plate 3, (The Scene with the Quack)" by William Hogarth, 1745

Prior to the nineteenth century European medical training and

practice was ostensibly self-regulated through a variety of antique

corporations, guilds or colleges. Among regular practitioners, university trained physicians formed a medical elite while provincial surgeons and apothecaries, who learnt their art through apprenticeship, made up the lesser ranks. In Old Regime France, licenses for medical practitioners were granted by the medical faculties

of the major universities, such as the Paris Faculty of Medicine.

Access was restricted and successful candidates, amongst other

requirements, had to pass examinations and pay regular fees. In the Austrian Empire medical licences were granted by the Universities of Prague and Vienna. Amongst the German states the top physicians were academically qualified and typically attached to medical colleges associated with the royal court. The theories and practices included the science of anatomy

and that the blood circulated by a pumping heart, and contained some

empirically gained information on progression of disease and about

surgery, but were otherwise unscientific, and were almost entirely

ineffective and dangerous.

Outside of these formal medical structures there were myriad

other medical practitioners, often termed irregulars, plying a range of

services and goods. The eighteenth-century medical marketplace, a period often referred to as the "Golden Age of quackery",

was a highly pluralistic one that lacked a well-defined and policed

division between "conventional" and "unconventional" medical

practitioners.

In much of continental Europe legal remedies served to control at least

the most egregious forms of "irregular" medical practice but the

medical market in both Britain and American was less restrained through

regulation. Quackery in the period prior to modern medical professionalisation

should not be considered equivalent to alternative medicine as those

commonly deemed quacks were not peripheral figures by default nor did

they necessarily promote oppositional and alternative medical systems.

Indeed, the charge of 'quackery', which might allege medical

incompetence, avarice or fraud, was levelled quite indiscriminately

across the varied classes of medical practitioners be they regular

medics, such as the hierarchical, corporate classes of physicians,

surgeons and apothecaries in England, or irregulars such as nostrum mongers, bonesetters and local wise-women.

Commonly, however, quackery was associated with a growing medical

entrepreneurship amongst both regular and irregular practitioners in the

provision of goods and services along with associated techniques of

advertisement and self-promotion in the medical marketplace. The constituent features of the medical marketplace during the eighteenth century were the development of medical consumerism

and a high degree of patient power and choice in the selection of

treatments, the limited efficacy of available medical therapies, and the absence of both medical professionalisation and enforced regulation of the market.

Medical professionalisation

In

the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries regular and irregular

medical practitioners became more clearly differentiated throughout much

of Europe. In part, this was achieved through processes of state-sanctioned medical regulation.

The different types of regulatory medical markets created across

nineteenth-century Europe and America reflected differing historical

patterns of state formation.

Where states had traditionally enjoyed strong, centralised power, such

as in the German states, government more easily assumed control of the

medical regulation. In states that had exercised weaker central power and adopted a free-market

model, such as in Britain, government gradually assumed greater control

over medical regulation as part of increasing state focus on issues of public health. This process was significantly complicated in Britain by the enduring existence of the historical medical colleges. A similar process is observable in America from the 1870s but this was facilitated by the absence of medical corporations.

Throughout the nineteenth century, however, most Western states

converged in the creation of legally delimited and semi-protected

medical markets. It is at this point that an "official" medicine, created in cooperation with the state and employing a scientific rhetoric of legitimacy, emerges as a recognisable entity and that the concept of alternative medicine as a historical category becomes tenable.

France provides perhaps one of the earliest examples of the

emergence of a state-sanctioned medical orthodoxy – and hence also of

the conditions for the development of forms of alternative medicine –

the beginnings of which can be traced to the late eighteenth century.

In addition to the traditional French medical faculties and the complex

hierarchies of practitioners over which they presided, the state

increasingly supported new institutions, such as the Société Royale de

Médecine (Royal Society of Medicine) which received its royal charter in 1778, that played a role in policing medical practice and the sale of medical nostrums. This system was radically transformed during the early phases of the French Revolution

when both the traditional faculties and the new institutions under

royal sponsorship were removed and an entirely unregulated medical

market was created.

This anarchic situation was reformed under the exigencies of war when

in 1793 the state established national control over medical education;

under Napoleon in 1803 state-control was extended over the licensing of medical practitioners. This latter reform introduced a new hierarchical division between practitioners in the creation of a medical élite of graduate physicians and surgeons, who were at liberty to practice throughout the state, and the lowly officiers de santé who received less training, could only offer their services to the poor, and were restricted in where they could practice. This national system of medical regulation under state-control, exported to regions of Napoleonic conquest such as Italy, the Rhineland and the Netherlands, became paradigmatic in the West and in countries adopting western medical systems. While offering state protection to licensed doctors and establishing a medical monopoly in principal it did not, however, remove competition from irregular practitioners.

Nineteenth-century non-conventional medicine

From

the late eighteenth century and more robustly from the mid-nineteenth

century a number of non-conventional medical systems developed in the

West which proposed oppositional medical systems, criticised orthodox

medical practitioners, emphasised patient-centredness, and offered

substitutes for the treatments offered by the medical mainstream.

While neither the medical marketplace nor irregular practitioners

disappeared during the nineteenth century, the proponents of alternative

medical systems largely differed from the entrepreneurial quacks of the

previous century in eschewing showy self-promotion and instead adopting

a more sober and serious self-presentation.

The relationship between medical orthodoxy and heterodoxy was complex,

both categories contained considerably variety, were subject to

substantial change throughout the period, and the divisions between the

two were frequently blurred.

Many alternative notions grew out of the Lebensreform

movement, which emphasized the goodness of nature, the harms to

society, people, and to nature caused by industrialization, the

importance of the whole person, body and mind, the power of the sun, and

the goodness of "the old ways".

The variety of alternative medical systems which developed during

this period can be approximately categorised according to the form of

treatment advocated. These were: those employing spiritual or

psychological therapies, such as hypnosis (mesmerism); nutritional therapies based upon special diets, such as medical botanism; drug and biological therapies such as homeopathy and hydrotherapy; and, manipulative physical therapies such as osteopathy and chiropractic massage. Non-conventional medicine might define health in terms of concepts of balance and harmony or espouse vitalistic doctrines of the body. Illness could be understood as due to the accretion of bodily toxins and impurities, to result from magical, spiritual,

or supernatural causes, or as arising from energy blockages in the body

such that healing actions might constitute energy transfer from

practitioner to patient.

Mesmerism

Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815)

Mesmerism is the medical system proposed in the late eighteenth century by the Viennese-trained physician, Franz Anton Mesmer (1734–1815), for whom it is named. The basis of this doctrine was Mesmer's claimed discovery of a new aetherial fluid, animal magnetism,

which, he contended, permeated the universe and the bodies of all

animate beings and whose proper balance was fundamental to health and

disease. Animal magnetism was but one of series of postulated subtle fluids and substances, such as caloric, phlogiston, magnetism, and electricity, which then suffused the scientific literature. It also reflected Mesmer's doctoral thesis, De Planatarum Influxu ("On the Influence of the Planets"), which had investigated the impact of the gravitational effect of planetary movements on fluid-filled bodily tissues. His focus on magnetism and the therapeutic potential of magnets was derived from his reading of Paracelsus, Athanasius Kircher and Johannes Baptista van Helmont.

The immediate impetus for his medical speculation, however, derived

from his treatment of a patient, Franzisca Oesterlin, who suffered from

episodic seizures and convulsions

which induced vomiting, fainting, temporary blindness and paralysis.

His cure consisted of placing magnets upon her body which consistently

produced convulsive episodes and a subsequent diminution of symptoms.

According to Mesmer, the logic of this cure suggested that health was

dependent upon the uninterrupted flow of a putative magnetic fluid and

that ill health was consequent to its blockage. His treatment methods

claimed to resolve this by either directly transferring his own

superabundant and naturally occurring animal magnetism to his patients

by touch or through the transmission of these energies from magnetic

objects.

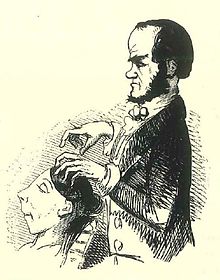

Caricature of a practitioner of animal magnetism treating a patient, c. 1780

By 1775 Mesmer's Austrian practice was prospering and he published the text Schrieben über die Magnetkur an einen auswärtigen Arzt which first outlined his thesis of animal magnetism.

In 1778, however, he became embroiled in a scandal resulting from his

treatment of a young, blind patient who was connected to the Viennese

court and relocated to Paris where he established a medical salon, "The

Society of Harmony", for the treatment of patients. Recruiting from a client-base drawn predominantly from society women of the middle- and upper-classes, Mesmer held group séances at his salubrious salon-clinic which was physically dominated by a large, lidded, wooden tank, known as the baquet, containing iron, glass and other material that Mesmer had magnetized and which was filled with "magnetized water".

At these sessions patients were enjoined to take hold of the metal rods

emanating from the tub which acted as a reservoir for the animal

magnetism derived from Mesmer and his clients.

Mesmer, through the apparent force of his will – not infrequently

assisted by an intense gaze or the administration of his wand – would

then direct these energies into the afflicted bodies of his patients

seeking to provoke either a "crisis" or a trance-like state; outcomes

which he believed essential for healing to occur.

Patient proclamations of cure ensured that Mesmer enjoyed considerable

and fashionable success in late-eighteenth-century Paris where he

occasioned something of a sensation and a scandal.

Popular caricature of mesmerism emphasised the eroticised nature

of the treatment as spectacle: "Here the physician in a coat of lilac or

purple, on which the most brilliant flowers have been painted in

needlework, speaks most consolingly to his patients: his arms softly

enfolding her sustain her in her spasms, and his tender burning eye

expresses his desire to comfort her". Responding chiefly to the hint of sexual impropriety and political radicalism imbuing these séances,

in 1784 mesmerism was subject to a commission of inquiry by a

royal-appointed scientific panel of the prestigious French Académie de

Médicine. Its findings were that animal magnetism had no basis in fact and that Mesmer's cures had been achieved through the power of suggestion.

The commission's report, if damaging to the personal status of Mesmer

and to the professional ambitions of those faculty physicians who had

adopted mesmeric practices,[n 5] did little to hinder the diffusion of the doctrine of animal magnetism.

1843 Punch magazine caricature depicting John Elliotson "playing the brain" of a working-class, mesmerised woman

In England mesmerism was championed by John Elliotson, Professor of Practical Medicine at University College London and the founder and president of the London Phrenological Society. A prominent and progressive orthodox physician, he was President of the Medico-Chirugical Society of London and an early adopter of the stethoscope in English medical practice.

He had been introduced to mesmerism in the summer of 1837 by the French

physician and former student of Mesmer, Dupotet, who is credited as the

most significant cross-channel influence on the development of

mesmerism in England.

Elliotson believed that animal magnetism provided the basis for a

consideration of the mind and will in material terms thus allowing for

their study as medical objects. Initially supported by The Lancet, a reformist medical journal,

he contrived to demonstrate the scientific properties of animal

magnetism as a physiological process on the predominantly female charity

patients under his care in the University College Hospital.

Working-class patients were preferred as experimental subjects to

exhibit the physical properties of mesmerism on the nervous system as,

being purportedly more animalistic and machine-like than their social

superiors, their personal characteristics were deemed less likely to

interfere with the experimental process.

He sought to reduce his subjects to the status of mechanical automata

claiming that he could, through the properties of animal magnetism and

the pacifying altered states of consciousness which it induced, "play"

their brains as if they were musical instruments.

Two Irish-born charity patients, the adolescent O'Key sisters,

emerged as particularly important to Elliotson's increasingly popular

and public demonstrations of mesmeric treatment. Initially, his

magnetising practices were used to treat the sisters' shared diagnosis

of hysteria and epilepsy in controlling or curtailing their convulsive

episodes. By the autumn of 1837 Elliotson had ceased to treat the O'Keys

merely as suitable objects for cure and instead sought to mobilise them

as diagnostic instruments.

When in states of mesmeric entrancement the O'Key sisters, due to the

apparent increased sensitization of their nervous system and sensory

apparatus, behaved as if they had the ability to see through solid

objects, including the human body, and thus aid in medical diagnosis. As

their fame rivalled that of Elliotson, however, the O'Keys behaved less

like human diagnostic machines and became increasingly intransigent to

medical authority and appropriated to themselves the power to examine,

diagnose, prescribe treatment and provide a prognosis.

The emergence of this threat to medical mastery in the form of a pair

of working-class, teenage girls without medical training aroused general

disquiet amongst the medical establishment and cost Elliotson one of

his early and influential supporters, the leading proponent of medical

reform, Thomas Wakley. Wakley, the editor of The Lancet,

had initially hoped that Elliotson's scientific experiments with animal

magnetism might further the agenda of medical reform in bolstering the

authority of the profession through the production of scientific truth

and, equally importantly in a period when the power-relations between

doctors and patients were being redefined, quiescent patient bodies.

Perturbed by the O'Key's provocative displays, Wakely convinced

Elliotson to submit his mesmeric practice to a trial in August 1838

before a jury of ten gentlemen during which he accused the sisters of

fraud and his colleague of gullibility.

Following a series of complaints issued to the Medical Committee of

University College Hospital they elected to discharge the O'Keys along

with other mesmeric subjects in the hospital and Elliotson resigned his

post in protest.

This set-back, while excluding Elliotson from the medical

establishment, ended neither his mesmeric career nor the career of

mesmerism in England. From 1842 he became an advocate of

phreno-mesmerism – an approach that amalgamated the tenets of phrenology with animal magnetism and that led to a split in the Phrenological Society. The following year he founded, together with the physician and then President of the Phrenological Society, William Collins Engledue, the principal journal on animal magnetism entitled The Zoist: A Journal of Cerebral Physiology and Mesmerism and their Application to Human Welfare, a quarterly publication which remained in print until its fifty-second issue in January 1856.

Mesmeric societies, frequently patronised by those among the scientific

and social elite were established in many major population centres in

Britain from the 1840s onwards.

Some sufficiently endowed societies, such as those in London, Bristol

and Dublin, Ireland, supported mesmeric infirmaries with permanent

mesmeric practitioners in their employ. Due to the competing rise of spiritualism and psychic research by the mid-1860s these mesmeric infirmaries had closed.

The First Operation under Ether,

painted by Robert Hinckley 1881–1896. This operation on the jaw of a

female patient took place in Boston on 19 October 1846. William Morton

acted as the anaesthetist and John Morrow was the surgeon

The 1840s in Britain also witnessed a deluge of travelling

magnetisers who put on public shows for paying audiences to demonstrate

their craft.

These mesmeric theatres, intended in part as a means of soliciting

profitable private clientele, functioned as public fora for debate

between skeptics and believers as to whether the performances were

genuine or constituted fraud.

In order to establish that the loss of sensation under mesmeric trance

was real, these itinerant mesmerists indulged in often quite violent

methods – including discharging firearms close to the ears of mesmerised

subjects, pricking them with needles, putting acid on their skin and

knives beneath their fingernails.

Such displays of the anaesthetic qualities of mesmerism inspired

some medical practitioners to attempt surgery on subjects under the

spell of magnetism.

In France, the first major operation of this kind had been trialled,

apparently successfully, as early as 1828 during a mastectomy procedure.

In Britain the first significant surgical procedure undertaken on a

patient while mesmerised occurred in 1842 when James Wombell, a labourer

from Nottingham, had his leg amputated.

Having been mesmerised for several days prior to the operation by a

barrister named William Topham, Wombell exhibited no signs of pain

during the operation and reported afterwards that the surgery had been

painless.

This account was disputed by many in the medical establishment who held

that Wombell had fraudulently concealed the pain of the amputation both

during and after the procedure. Undeterred, in 1843 Elliotson continued to advocate for the use of animal magnetism in surgery publishing Numerous Cases of Surgical Operation without Pain in the Mesmeric State.

This marked the beginning of a campaign by London mesmerists to gain a

foothold for the practice within British hospitals by convincing both

doctors and the general public of the value of surgical mesmerism.

Mesmeric surgery enjoyed considerable success in the years from 1842 to

1846 and colonial India emerged as a particular stronghold of the

practice; word of its success was propagated in Britain through the Zoist and the publication in 1846 of Mesmerism in India and its Practical Application in Surgery and Medicine

by James Esdaile, a Scottish surgeon with the East India Company and

the chief proponent of animal magnetism in the subcontinent.

Although a few surgeons and dentists had undertaken fitful

experiments with anaesthetic substances in the preceding years, it was

only in 1846 that use of ether in surgery was popularised amongst

orthodox medical practitioners.

This was despite the fact that the desensitising effects of widely

available chemicals like ether and nitrous oxide were commonly known and

had formed part of public and scientific displays over the previous

half-century.

A feature of the dissemination of magnetism in the New World was its increasing association with spiritualism. By the 1830s mesmerism was making headway in the United States amongst figures like the intellectual progenitor of the New Thought movement, Phineas Parkhurst Quimby, whose treatment combined verbal suggestion with touch. Quimby's most celebrated "disciple", Mary Baker Eddy, would go on to found the "medico-religious hybrid", Christian Science, in the latter half of the nineteenth century. In the 1840s the American spiritualist Andrew Jackson Davis

sought to combine animal magnetism with spiritual beliefs and

postulated that bodily health was dependent upon the unobstructed

movement of the "spirit", conceived as a fluid substance, throughout the

body. As with Quimby, Davis's healing practice involved the use of

touch.

Osteopathy and chiropractic manipulation

Deriving from the tradition of ‘bone-setting’ and a belief in the flow of supernatural energies in the body (vitalism), both osteopathy and chiropractic developed in the USA in the late 19th century. The British School of Osteopathy was established in 1917 but it was the 1960s before the first chiropractic college was established in the UK.

Chiropractic theories and methods (which are concerned with

subluxations or small displacements of the spine and other joints) do

not accord with orthodox medicine’s current knowledge of the

biomechanics of the spine. in addition to teaching osteopathic manipulative medicine

(OMM) and theory, osteopathic colleges in the US gradually came to have

the same courses and requirements as biomedical schools, whereby

osteopathic doctors (ODs) who did practice OMM were considered to be

practicing conventional biomedicine in the US. The passing of the

Osteopaths Act (1993) and the Chiropractors Act (1994), however, created

for the first time autonomous statutory regulation for two CAM

therapies in the UK.

History of chiropractic

Chiropractic began in the United States in 1895. when Daniel David Palmer

performed the first chiropractic adjustment on a partially deaf

janitor, who then claimed he could hear better as a result of the

manipulation. Palmer opened a school of chiropractic two years later. Chiropractic's early philosophy was rooted in vitalism, naturalism, magnetism, spiritualism and other unscientific constructs. Palmer claimed to merge science and metaphysics.

Palmer's first descriptions and underlying philosophy of chiropractic

described the body as a "machine" whose parts could be manipulated to

produce a drugless cure, that spinal manipulation could improve health,

and that the effects of chiropractic spinal manipulation as being

mediated primarily by the nervous system.

Despite their similarities, osteopathic practitioners sought to differentiate themselves by seeking regulation of the practices. In a 1907 test of the new law, a Wisconsin based chiropractor was charged with practicing osteopathic medicine without a license. Practicing medicine without a license led to many chiropractors, including D.D. Palmer, being jailed.

Chiropractors won their first test case, but prosecutions instigated

by state medical boards became increasingly common and successful.

Chiropractors responded with political campaigns for separate licensing

statutes, from osteopaths, eventually succeeding in all fifty states,

from Kansas in 1913 through Louisiana in 1974.

Divisions developed within the chiropractic profession, with "mixers" combining spinal adjustments with other treatments, and "straights" relying solely on spinal adjustments. A conference sponsored by the National Institutes of Health in 1975 spurred the development of chiropractic research. In 1987, the American Medical Association called chiropractic an "unscientific cult" and boycotted it until losing a 1987 antitrust case.

Histories of individual traditional medical systems

Ayurvedic medicine

Ayurveda or ayurvedic medicine

has more than 5,000 years of history, now re-emerging as texts become

increasingly accessible in modern English translations. These texts

attempt to translate the Sanskrit versions that have remained hidden in

India since British occupation from 1755–1947.

As modern archaeological evidence from Harappa and Mohenja-daro is

distributed, Ayurveda has now been accepted as the world's oldest

concept of health and disease discovered by man and the oldest

continuously practiced system of medicine. Ayurveda is a world view that

advocates man’s allegiance and surrender to the forces of Nature that

are increasingly revealed in modern physics, chemistry and biology. It

is based on an interpretation of disease and health that parallels the

forces of nature, observing the sun's fire and making analogies to the

fires of the body; observing the flows in Nature and describing flows in

the body, terming the principle as Vata; observing the transformations

in Nature and describing transformations in the body, terming the

principle as Pitta; and observing the stability in Nature and describing

stability in the body, terming the principle as Kapha.

Ayurveda can be defined as the system of medicine described in

the great medical encyclopedias associated with the names Caraka,

Suśruta, and Bheḷa, compiled and re-edited over several centuries from

about 200 BCE to about 500 CE and written in Sanskrit. These discursive writings were gathered and systematized in about 600 CE by Vāgbhaṭa, to produce the Aṣṭāṅgahṛdayasaṃhitā ('Heart of Medicine Compendium') that became the most popular and widely used textbook of ayurvedic medicine in history. Vāgbhaṭa's work was translated into many other languages and became influential throughout Asia.

Its prehistory goes back to Vedic culture and its proliferation in written form flourished in Buddhist times. Although the hymns of the Atharvaveda and the Ṛgveda

mention some herbal medicines, protective amulets, and healing prayers

that recur in the ciphered slokas of later ayurvedic treatises, the

earliest historical mention of the main structural and theoretical

categories of ayurvedic medicine occurs in the Buddhist Pāli Tripiṭaka, or Canon.

Ayurveda originally derived from the Vedas, as the name suggests,

and was first organized and captured in Sanskrit in ciphered form by

physicians teaching their students judicious practice of healing. These

ciphers are termed slokas and are purposefully designed to include

several meanings, to be interpreted appropriately, known as 'tantra

yukti' by the knowledgeable practitioner. Ayu means longevity or healthy

life, and veda means human-interpreted and observable truths and

provable science. The principles of Ayurveda include systematic means

for allowing evidence, including truth by observation and

experimentation, pratyaksha; attention to teachers with sufficient

experience, aptoupadesha; analogy to things seen in Nature, anumana; and

logical argument, yukti.

It was founded on several principles, including yama (time) and

niyama (self-regulation) and placed emphasis on routines and adherence

to cycles, as seen in Nature. For example, it directs that habits should

be regulated to coincide with the demands of the body rather than the

whimsical mind or evolving and changing nature of human intelligence.

Thus, for the follower of ayurvedic medicine, food should only be taken

when they are instinctively hungry rather than at an arbitrarily set

meal-time. Ayurveda also teaches that when a person is tired, it is not

wise to eat food or drink, but to rest, as the body's fire is low and

must gather energy in order to alight the enzymes that are required to

digest food. The same principles of regulated living, called Dinacharya,

direct that work is the justification for rest and in order to get

sufficient sleep, one should subject the body to rigorous exercise.

Periodic fasting, or abstaining from all food and drink for short

durations of one or two days helps regulate the elimination process and

prevents illness. It is only in later years that practitioners of this

system saw that people were not paying for their services, and in order

to get their clients to pay, they introduced herbal remedies to begin

with and later even started using metals and inorganic chemical

compositions in the form of pills or potions to deal with symptoms.

Emigration from the Indian sub-continent in the 1850s brought practitioners of Ayurveda (‘Science of Life’). a medical system dating back over 2,500 years,

its adoption outside the Asian communities was limited by its lack of

specific exportable skills and English-language reference books until

adapted and modernised forms, New Age Ayurveda and Maharishi Ayurveda,

came under the umbrella of CAM in the 1970s to Europe.

In Britain, Unani practitioners are known as hakims and Ayurvedic

practitioners are known as vaidyas. Having its origins in the Ayurveda, Indian Naturopathy

incorporates a variety of holistic practices and natural remedies and

became increasingly popular after the arrival of the post-Second World

War wave of Indian immigrants.[citation needed] The Persian work for Greek,Unani

medicines uses some similar materials as Ayurveda but are based on

philosophy closer to Greek and Arab sources than to Ayurveda.

Exiles fleeing the war between Yemen and Aden in the 1960s settled

nearby the ports of Cardiff and Liverpool and today practitioners of

this Middle Eastern medicine are known as vaids..

In the US, Ayurveda has increased popularity since the 1990s, as

Indian-Americans move into the mainstream media, and celebrities visit

India more frequently. In addition, many Americans go to India for

medical tourism to avail of reputed Ayurvedic medical centers that are

licensed and credentialed by the Indian government and widely legitimate

as a medical option for chronic medical conditions. AAPNA, the

Association of Ayurvedic Professionals of North America, www.aapna.org,

has over 600 medical professional members, including trained vaidyas

from accredited schools in India credentialed by the Indian government,

who are now working as health counselors and holistic practitioners in

the US. There are over 40 schools of Ayurveda throughout the US,

providing registered post-secondary education and operating mostly as

private ventures outside the legitimized medical system, as there is no

approval system yet in the US Dept of Education. Practitioners

graduating from these schools and arriving with credentials from India

practice legally through the Health Freedom Act, legalized in 13 states.

Credentialing and a uniform standard of education is being developed by

the international CAC, Council of Ayurvedic Credentialing,

www.cayurvedac.com,

in consideration of the licensed programs in Ayurveda operated under

the Government of India's Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Dept of

AYUSH. In India, there are over 600,000 practicing physicians of

Ayurveda. Ayurveda is a legal and legitimate medical system in many

countries of South Asia.

Chinese culture

Traditional Chinese medicine has more than 4,000 years of history as a system of medicine that is based on a philosophical concept of balance ( yin and yang, Qi, Blood, Jing, Bodily fluids, the Five Elements, the emotions, and the spirit) approach to health that is rooted in Taoist philosophy and Chinese culture. As such, the concept of it as an alternative form of therapeutic practise is only found in the Western world.

The arrival into Britain of thousands of Chinese in the 1970s introduced Traditional Chinese Medicine – a system dating back to the Bronze Age or earlier that used acupuncture, herbs, diet and exercise. Today there are more than 2,000 registered practitioners in the UK.

Since the 1970s

Until

the 1970s, western practitioners that were not part of the medical

establishment were referred to "irregular practitioners", and were

dismissed by the medical establishment as unscientific or quackery.[1] Irregular practice became increasingly marginalized as quackery

and fraud, as western medicine increasingly incorporated scientific

methods and discoveries, and had a corresponding increase in success of

its treatments. In the 1970s, irregular practices were grouped with

traditional practices of nonwestern cultures, and with other unproven or

disproven practices that were not part of biomedicine, and the entire

group began to be marketed and promoted as "alternative medicine". Following the counterculture movement

of the 1960s, misleading marketing campaigns promoting "alternative

medicine" as an effective "alternative" to biomedicine, and with

changing social attitudes about not using chemicals, challenging the

establishment and authority of any kind, sensitivity to giving equal

measure to values and beliefs of other cultures and their practices

through cultural relativism, adding postmodernism and deconstructivism

to ways of thinking about science and its deficiencies, and with

growing frustration and desperation by patients about limitations and

side effects of science-based medicine,

use of alternative medicine in the west began to rise, then had

explosive growth beginning in the 1990s, when senior level political

figures began promoting alternative medicine, and began diverting

government medical research funds into research of alternative,

complementary, and integrative medicine.

1970s through 1980s

1990s to present

Sen. Tom Harkin at a press conference.

In 1991, after United States Senator Thomas Harkin became convinced his allergies were cured by taking bee pollen

pills, he used $2 million of his discretionary funds to create the

Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM), to test the efficacy of

alternative medicine and alert the public as the results of testing its

efficacy.

The OAM mission statement was that it was “dedicated to exploring

complementary and alternative healing practices in the context of

rigorous science; training complementary and alternative medicine

researchers; and disseminating authoritative information to the public

and professionals.” Joseph M. Jacobs

was appointed the first director of the OAM in 1992. Jacobs' insistence

on rigorous scientific methodology caused friction with Senator Harkin.

Harkin criticized the "unbendable rules of randomized clinical trials"

and, citing his use of bee pollen to treat his allergies, stated: "It is

not necessary for the scientific community to understand the process

before the American public can benefit from these therapies."

Increasing political resistance to the use of scientific methodology

was publicly criticized by Dr. Jacobs and another OAM board member

complained that “nonsense has trickled down to every aspect of this

office”. In 1994, Senator Harkin responded by appearing on television

with cancer patients who blamed Dr. Jacobs for blocking their access to

untested cancer treatment, leading Jacobs to resign in frustration. The

OAM drew increasing criticism from eminent members of the scientific

community, from a Nobel laureate criticizing the degrading parts of the

NIH to the level a cover for quackery, and the president of the American Physical Society

criticizing spending on testing practices that “violate basic laws of

physics and more clearly resemble witchcraft”. In 1998, the President of

the North Carolina Medical Association publicly called for shutting down the OAM. The NIH Director placed the OAM under more strict scientific NIH control.

In 1998, Sen. Harkin responded to the criticism and stricter

scientific controls by the NIH, by raising the OAM to the level of an

independent center, increasing its budget to $90 million annually, and

renaming it to be the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine

(NCCAM). The United States Congress approved the appropriations without

dissent. NCCAM had a mandate to promote a more rigorous and scientific

approach to the study of alternative medicine, research training and

career development, outreach, and integration. In 2014 the agency was

renamed to the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health

(NCCIH). The NCCIH charter requires that 12 of the 18 council members

shall be selected with a preference to selecting leading representatives

of complementary and alternative medicine, 9 of the members must be

licensed practitioners of alternative medicine, 6 members must be

general public leaders in the fields of public policy, law, health

policy, economics, and management, and 3 members must represent the

interests of individual consumers of complementary and alternative

medicine.

By 2009, the NCCIH budget had grown from annual spending of about

$2 million at its inception, to $123 million annually. In 2009, after a

history of 17 years of government testing produced almost no clearly

proven efficacy of alternative therapies, Senator Harkin complained,

“One of the purposes of this center was to investigate and validate

alternative approaches. Quite frankly, I must say publicly that it has

fallen short. It think quite frankly that in this center and in the

office previously before it, most of its focus has been on disproving

things rather than seeking out and approving.”

Members of the scientific and biomedical communities complained that

after a history of 17 years of being tested, at a cost of over $2.5

Billion on testing scientifically and biologically implausible

practices, almost no alternative therapy showed clear efficacy.

From 1990 to 1997, use of alternative medicine in the US increased by 25%, with a corresponding 50% increase in expenditures. By 2013, 50% of Americans were using alternative medicine, and annual spending on CAM in the US was $34 Billion.

Other periods

The

terms ‘alternative’ and ‘complementary’ tend to be used interchangeably

to describe a wide diversity of therapies that attempt to use the

self-healing powers of the body by amplifying natural recuperative

processes to restore health. In ancient Greece the Hippocratic

movement, commonly regarded as the fathers of medicine, actually gave

rise to modern naturopathy and indeed much of today’s CAM.

They placed great emphasis on a good diet and healthy lifestyle to

restore equilibrium; drugs were used more to support healing than to

cure disease.

Complementary medicines have evolved through history and become

formalised from primitive practices; although many were developed during

the 19th century as alternatives to the sometimes harmful practices of

the time, such as blood-lettings and purgation. In the UK, the medical

divide between CAM and conventional medicine has been characterised by

conflict, intolerance and prejudice on both sides and during the early

20th century CAM was virtually outlawed in Britain: healers were seen as

freaks and hypnotherapists were subject to repeated attempts at legal

restriction.

The alternative health movement is now accepted as part of modern

life, having progressed from a grass-roots revival in the 1960s reacting

against environmental degradation, unhealthy diets and rampant

consumerism.

Until the arrival of the Romans in AD43, medical practices were

limited to a basic use of plant materials, prayers and incantations.

Having assimilated the corpus of Hippocrates, the Romans brought with

them a vast reparatory of herbal treatments and introduced the concept of the hospital as a centralised treatment centre. In Britain, hydrotherapy (the use of water either internally or externally to maintain health and prevent disease) can be traced back to Roman spas. This was augmented by practices from the Far East and China introduced by traders using the Silk Road.

During the Catholic and Protestant witch-hunts from the 14th to

the 17th centuries, the activities of traditional folk-healers were

severely curtailed and knowledge was often lost as it existed only as an

oral tradition. The widespread emigration from Europe to North America

in the 18th and 19th centuries included both the knowledge of herbalism

and some of the plants themselves. This was combined with Native

American medicine and then re-imported to the UK where it re-integrated

with the surviving herbal traditions to evolve as today’s medical herbalism movement.

The natural law of similia similibus curantur, or ‘like is cured

by like’, was recognised by Hippocrates but was only developed as a

practical healing system in the early 19th century by a German, Dr

Samuel Hahnemann. Homeopathy

was brought to the UK in the 1830s by a Dr Quinn who introduced it to

the British aristocracy, whose patronage continues to this day. Despite

arousing controversy in conventional medical circles, homeopathy is

available under the National Health Service, and in Scotland

approximately 25% of GPs hold qualifications in homeopathy or have

undergone some homeopathic training.

The impact on CAM of mass immigration into the UK is continuing into the 21st century. Originating in Japan, cryotherapy

has been developed by Polish researchers into a system that claims to

produce lasting relief from a variety of conditions such as rheumatism,

psoriasis and muscle pain. Patients spend a few minutes in a chamber cooled to −110 °C, during which skin temperature drops some 12 °C.

The use of CAM is widespread and increasing across the developed

world. The British are presented with a wide choice of treatments from

the traditional to the innovative and technological. Section 60 of the

Health Act 1999 allows for new health professions to be created by Order

rather than primary legislation.

This raises issues of public health policy which balance regulation,

training, research, evidence-base and funding against freedom of choice

in a culturally diverse society

Relativist perspective

The term alternative medicine refers to systems of medical thought and practice which function[citation needed] as alternatives to or subsist outside of conventional, mainstream medicine.

Alternative medicine cannot exist absent an established, authoritative

and stable medical orthodoxy to which it can function as an alternative.

Such orthodoxy was only established in the West during the nineteenth century through processes of regulation, association, institution building and systematised medical education.