Cell-count distribution featuring cellular differentiation for three types of cells (progenitor , osteoblast , and chondrocyte ) exposed to pro-osteoblast stimulus.

Cellular differentiation is the process where a cell changes from one cell type to another. Usually, the cell changes to a more specialized type. Differentiation occurs numerous times during the development of a multicellular organism as it changes from a simple zygote to a complex system of tissues and cell types. Differentiation continues in adulthood as adult stem cells divide and create fully differentiated daughter cells during tissue repair and during normal cell turnover. Some differentiation occurs in response to antigen exposure. Differentiation dramatically changes a cell's size, shape, membrane potential, metabolic activity, and responsiveness to signals. These changes are largely due to highly controlled modifications in gene expression and are the study of epigenetics. With a few exceptions, cellular differentiation almost never involves a change in the DNA sequence itself. Thus, different cells can have very different physical characteristics despite having the same genome.

A specialized type of differentiation, known as 'terminal

differentiation', is of importance in some tissues, for example

vertebrate nervous system, striated muscle, epidermis and gut. During

terminal differentiation, a precursor cell formerly capable of cell

division, permanently leaves the cell cycle, dismantles the cell cycle

machinery and often expresses a range of genes characteristic of the

cell's final function (e.g. myosin and actin for a muscle cell).

Differentiation may continue to occur after terminal differentiation if

the capacity and functions of the cell undergo further changes.

Among dividing cells, there are multiple levels of cell potency,

the cell's ability to differentiate into other cell types. A greater

potency indicates a larger number of cell types that can be derived. A

cell that can differentiate into all cell types, including the placental

tissue, is known as totipotent. In mammals, only the zygote and subsequent blastomeres

are totipotent, while in plants, many differentiated cells can become

totipotent with simple laboratory techniques. A cell that can

differentiate into all cell types of the adult organism is known as pluripotent. Such cells are called meristematic cells in higher plants and embryonic stem cells

in animals, though some groups report the presence of adult pluripotent

cells. Virally induced expression of four transcription factors Oct4, Sox2, c-Myc, and KIF4 (Yamanaka factors) is sufficient to create pluripotent (iPS) cells from adult fibroblasts. A multipotent cell is one that can differentiate into multiple different, but closely related cell types. Oligopotent cells are more restricted than multipotent, but can still differentiate into a few closely related cell types. Finally, unipotent cells can differentiate into only one cell type, but are capable of self-renewal. In cytopathology, the level of cellular differentiation is used as a measure of cancer progression. "Grade" is a marker of how differentiated a cell in a tumor is.

Mammalian cell types

Three basic categories of cells make up the mammalian body: germ cells, somatic cells, and stem cells. Each of the approximately 37.2 trillion (3.72x1013) cells in an adult human has its own copy or copies of the genome except certain cell types, such as red blood cells, that lack nuclei in their fully differentiated state. Most cells are diploid; they have two copies of each chromosome.

Such cells, called somatic cells, make up most of the human body, such

as skin and muscle cells. Cells differentiate to specialize for

different functions.

Germ line cells are any line of cells that give rise to gametes—eggs

and sperm—and thus are continuous through the generations. Stem cells,

on the other hand, have the ability to divide for indefinite periods and

to give rise to specialized cells. They are best described in the

context of normal human development.

Development begins when a sperm fertilizes an egg

and creates a single cell that has the potential to form an entire

organism. In the first hours after fertilization, this cell divides into

identical cells. In humans, approximately four days after fertilization

and after several cycles of cell division, these cells begin to

specialize, forming a hollow sphere of cells, called a blastocyst. The blastocyst has an outer layer of cells, and inside this hollow sphere, there is a cluster of cells called the inner cell mass.

The cells of the inner cell mass go on to form virtually all of the

tissues of the human body. Although the cells of the inner cell mass can

form virtually every type of cell found in the human body, they cannot

form an organism. These cells are referred to as pluripotent.

Pluripotent stem cells undergo further specialization into multipotent progenitor cells that then give rise to functional cells. Examples of stem and progenitor cells include:

- Radial glial cells (embryonic neural stem cells) that give rise to excitatory neurons in the fetal brain through the process of neurogenesis.

- Hematopoietic stem cells (adult stem cells) from the bone marrow that give rise to red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets

- Mesenchymal stem cells (adult stem cells) from the bone marrow that give rise to stromal cells, fat cells, and types of bone cells

- Epithelial stem cells (progenitor cells) that give rise to the various types of skin cells

- Muscle satellite cells (progenitor cells) that contribute to differentiated muscle tissue.

A pathway that is guided by the cell adhesion molecules consisting of four amino acids, arginine, glycine, asparagine, and serine, is created as the cellular blastomere differentiates from the single-layered blastula to the three primary layers of germ cells in mammals, namely the ectoderm, mesoderm and endoderm

(listed from most distal (exterior) to proximal (interior)). The

ectoderm ends up forming the skin and the nervous system, the mesoderm

forms the bones and muscular tissue, and the endoderm forms the internal

organ tissues.

Dedifferentiation

Micrograph of a liposarcoma

with some dedifferentiation, that is not identifiable as a liposarcoma,

(left edge of image) and a differentiated component (with lipoblasts and increased vascularity (right of image)). Fully differentiated (morphologically benign) adipose tissue (center of the image) has few blood vessels. H&E stain.

Dedifferentiation, or integration is a cellular process often seen in more basal life forms such as worms and amphibians in which a partially or terminally differentiated cell reverts to an earlier developmental stage, usually as part of a regenerative process. Dedifferentiation also occurs in plants. Cells in cell culture

can lose properties they originally had, such as protein expression, or

change shape. This process is also termed dedifferentiation.

Some believe dedifferentiation is an aberration of the normal development cycle that results in cancer, whereas others believe it to be a natural part of the immune response lost by humans at some point as a result of evolution.

A small molecule dubbed reversine, a purine analog, has been discovered that has proven to induce dedifferentiation in myotubes. These dedifferentiated cells could then redifferentiate into osteoblasts and adipocytes.

Diagram exposing several methods used to revert adult somatic cells to totipotency or pluripotency.

Mechanisms

Mechanisms of cellular differentiation.

Each specialized cell type in an organism expresses a subset of all the genes that constitute the genome of that species. Each cell type is defined by its particular pattern of regulated gene expression.

Cell differentiation is thus a transition of a cell from one cell type

to another and it involves a switch from one pattern of gene expression

to another. Cellular differentiation during development can be

understood as the result of a gene regulatory network.

A regulatory gene and its cis-regulatory modules are nodes in a gene

regulatory network; they receive input and create output elsewhere in

the network. The systems biology

approach to developmental biology emphasizes the importance of

investigating how developmental mechanisms interact to produce

predictable patterns (morphogenesis). (However, an alternative view has been proposed recently. Based on stochastic

gene expression, cellular differentiation is the result of a Darwinian

selective process occurring among cells. In this frame, protein and gene

networks are the result of cellular processes and not their cause.)

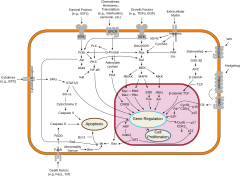

An overview of major signal transduction pathways.

A few evolutionarily

conserved types of molecular processes are often involved in the

cellular mechanisms that control these switches. The major types of

molecular processes that control cellular differentiation involve cell signaling.

Many of the signal molecules that convey information from cell to cell

during the control of cellular differentiation are called growth factors. Although the details of specific signal transduction

pathways vary, these pathways often share the following general steps.

A ligand produced by one cell binds to a receptor in the extracellular

region of another cell, inducing a conformational change in the

receptor. The shape of the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor changes,

and the receptor acquires enzymatic activity. The receptor then

catalyzes reactions that phosphorylate other proteins, activating them.

A cascade of phosphorylation reactions eventually activates a dormant

transcription factor or cytoskeletal protein, thus contributing to the

differentiation process in the target cell. Cells and tissues can vary in competence, their ability to respond to external signals.

Signal induction refers to cascades of signaling events, during which a cell or tissue signals to another cell or tissue to influence its developmental fate. Yamamoto and Jeffery investigated the role of the lens in eye formation in cave- and surface-dwelling fish, a striking example of induction. Through reciprocal transplants, Yamamoto and Jeffery

found that the lens vesicle of surface fish can induce other parts of

the eye to develop in cave- and surface-dwelling fish, while the lens

vesicle of the cave-dwelling fish cannot.

Other important mechanisms fall under the category of asymmetric cell divisions,

divisions that give rise to daughter cells with distinct developmental

fates. Asymmetric cell divisions can occur because of asymmetrically

expressed maternal cytoplasmic determinants or because of signaling. In the former mechanism, distinct daughter cells are created during cytokinesis

because of an uneven distribution of regulatory molecules in the parent

cell; the distinct cytoplasm that each daughter cell inherits results

in a distinct pattern of differentiation for each daughter cell. A

well-studied example of pattern formation by asymmetric divisions is body axis patterning in Drosophila. RNA

molecules are an important type of intracellular differentiation

control signal. The molecular and genetic basis of asymmetric cell

divisions has also been studied in green algae of the genus Volvox, a model system for studying how unicellular organisms can evolve into multicellular organisms. In Volvox carteri,

the 16 cells in the anterior hemisphere of a 32-cell embryo divide

asymmetrically, each producing one large and one small daughter cell.

The size of the cell at the end of all cell divisions determines whether

it becomes a specialized germ or somatic cell.

Epigenetic control

Since each cell, regardless of cell type, possesses the same genome, determination of cell type must occur at the level of gene expression. While the regulation of gene expression can occur through cis- and trans-regulatory elements including a gene's promoter and enhancers, the problem arises as to how this expression pattern is maintained over numerous generations of cell division. As it turns out, epigenetic

processes play a crucial role in regulating the decision to adopt a

stem, progenitor, or mature cell fate. This section will focus primarily

on mammalian stem cells.

In systems biology and mathematical modeling of gene regulatory

networks, cell-fate determination is predicted to exhibit certain

dynamics, such as attractor-convergence (the attractor can be an

equilibrium point, limit cycle or strange attractor) or oscillatory.

Importance of epigenetic control

The

first question that can be asked is the extent and complexity of the

role of epigenetic processes in the determination of cell fate. A clear

answer to this question can be seen in the 2011 paper by Lister R, et al. on aberrant epigenomic programming in human induced pluripotent stem cells. As induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) are thought to mimic embryonic stem cells

in their pluripotent properties, few epigenetic differences should

exist between them. To test this prediction, the authors conducted

whole-genome profiling of DNA methylation patterns in several human embryonic stem cell (ESC), iPSC, and progenitor cell lines.

Female adipose cells, lung fibroblasts, and foreskin fibroblasts were reprogrammed into induced pluripotent state with the OCT4, SOX2, KLF4, and MYC genes. Patterns of DNA methylation in ESCs, iPSCs, somatic cells were compared. Lister R, et al. observed significant resemblance in methylation levels between embryonic and induced pluripotent cells. Around 80% of CG dinucleotides

in ESCs and iPSCs were methylated, the same was true of only 60% of CG

dinucleotides in somatic cells. In addition, somatic cells possessed

minimal levels of cytosine methylation in non-CG dinucleotides, while

induced pluripotent cells possessed similar levels of methylation as

embryonic stem cells, between 0.5 and 1.5%. Thus, consistent with their

respective transcriptional activities, DNA methylation patterns, at least on the genomic level, are similar between ESCs and iPSCs.

However, upon examining methylation patterns more closely, the

authors discovered 1175 regions of differential CG dinucleotide

methylation between at least one ES or iPS cell line. By comparing these

regions of differential methylation with regions of cytosine

methylation in the original somatic cells, 44-49% of differentially

methylated regions reflected methylation patterns of the respective

progenitor somatic cells, while 51-56% of these regions were dissimilar

to both the progenitor and embryonic cell lines. In vitro-induced

differentiation of iPSC lines saw transmission of 88% and 46% of hyper

and hypo-methylated differentially methylated regions, respectively.

Two conclusions are readily apparent from this study. First,

epigenetic processes are heavily involved in cell fate determination, as

seen from the similar levels of cytosine methylation between induced

pluripotent and embryonic stem cells, consistent with their respective

patterns of transcription.

Second, the mechanisms of de-differentiation (and by extension,

differentiation) are very complex and cannot be easily duplicated, as

seen by the significant number of differentially methylated regions

between ES and iPS cell lines. Now that these two points have been

established, we can examine some of the epigenetic mechanisms that are

thought to regulate cellular differentiation.

Mechanisms of epigenetic regulation

Pioneer factor|Pioneering factors (Oct4, Sox2, Nanog)

Three transcription factors, OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG – the first two of which are used in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) reprogramming, along with Klf4 and c-Myc – are highly expressed in undifferentiated embryonic stem cells and are necessary for the maintenance of their pluripotency. It is thought that they achieve this through alterations in chromatin structure, such as histone modification

and DNA methylation, to restrict or permit the transcription of target

genes. While highly expressed, their levels require a precise balance to

maintain pluripotency, perturbation of which will promote

differentiation towards different lineages based on how the gene

expression levels change. Differential regulation of Oct-4 and SOX2 levels have been shown to precede germ layer fate selection. Increased levels of Oct4 and decreased levels of Sox2 promote a mesendodermal fate, with Oct4 actively suppressing genes associated with a neural ectodermal

fate. Similarly, Increased levels of Sox2 and decreased levels of Oct4

promote differentiation towards a neural ectodermal fate, with Sox2

inhibiting differentiation towards a mesendodermal fate. Regardless of

the lineage cells differentiate down, suppression of NANOG has been identified as a necessary prerequisite for differentiation.

Polycomb repressive complex (PRC2)

In the realm of gene silencing, Polycomb repressive complex 2, one of two classes of the Polycomb group (PcG) family of proteins, catalyzes the di- and tri-methylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27me2/me3).

By binding to the H3K27me2/3-tagged nucleosome, PRC1 (also a complex of

PcG family proteins) catalyzes the mono-ubiquitinylation of histone H2A

at lysine 119 (H2AK119Ub1), blocking RNA polymerase II activity and resulting in transcriptional suppression.

PcG knockout ES cells do not differentiate efficiently into the three

germ layers, and deletion of the PRC1 and PRC2 genes leads to increased

expression of lineage-affiliated genes and unscheduled differentiation. Presumably, PcG complexes are responsible for transcriptionally repressing differentiation and development-promoting genes.

Trithorax group proteins (TrxG)

Alternately,

upon receiving differentiation signals, PcG proteins are recruited to

promoters of pluripotency transcription factors. PcG-deficient ES cells

can begin differentiation but cannot maintain the differentiated

phenotype.

Simultaneously, differentiation and development-promoting genes are

activated by Trithorax group (TrxG) chromatin regulators and lose their

repression.

TrxG proteins are recruited at regions of high transcriptional

activity, where they catalyze the trimethylation of histone H3 lysine 4 (H3K4me3) and promote gene activation through histone acetylation.

PcG and TrxG complexes engage in direct competition and are thought to

be functionally antagonistic, creating at differentiation and

development-promoting loci what is termed a "bivalent domain" and

rendering these genes sensitive to rapid induction or repression.

DNA methylation

Regulation of gene expression is further achieved through DNA methylation, in which the DNA methyltransferase-mediated methylation of cytosine residues in CpG dinucleotides maintains heritable repression by controlling DNA accessibility.

The majority of CpG sites in embryonic stem cells are unmethylated and

appear to be associated with H3K4me3-carrying nucleosomes. Upon differentiation, a small number of genes, including OCT4 and NANOG,

are methylated and their promoters repressed to prevent their further

expression. Consistently, DNA methylation-deficient embryonic stem cells

rapidly enter apoptosis upon in vitro differentiation.

Nucleosome positioning

While the DNA sequence

of most cells of an organism is the same, the binding patterns of

transcription factors and the corresponding gene expression patterns are

different. To a large extent, differences in transcription factor

binding are determined by the chromatin accessibility of their binding

sites through histone modification and/or pioneer factors. In particular, it is important to know whether a nucleosome is covering a given genomic binding site or not. This can be determined using a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay.

Histone acetylation and methylation

DNA-nucleosome

interactions are characterized by two states: either tightly bound by

nucleosomes and transcriptionally inactive, called heterochromatin, or loosely bound and usually, but not always, transcriptionally active, called euchromatin.

The epigenetic processes of histone methylation and acetylation, and

their inverses demethylation and deacetylation primarily account for

these changes. The effects of acetylation and deacetylation are more

predictable. An acetyl group is either added to or removed from the

positively charged Lysine residues in histones by enzymes called histone acetyltransferases or histone deacteylases,

respectively. The acetyl group prevents Lysine's association with the

negatively charged DNA backbone. Methylation is not as straightforward,

as neither methylation nor demethylation consistently correlate with

either gene activation or repression. However, certain methylations have

been repeatedly shown to either activate or repress genes. The

trimethylation of lysine 4 on histone 3 (H3K4Me3) is associated with

gene activation, whereas trimethylation of lysine 27 on histone 3

represses genes.

In stem cells

During differentiation, stem cells

change their gene expression profiles. Recent studies have implicated a

role for nucleosome positioning and histone modifications during this

process.

There are two components of this process: turning off the expression of

embryonic stem cell (ESC) genes, and the activation of cell fate genes.

Lysine specific demethylase 1 (KDM1A) is thought to prevent the use of enhancer regions of pluripotency genes, thereby inhibiting their transcription. It interacts with Mi-2/NuRD complex (nucleosome remodelling and histone deacetylase) complex, giving an instance where methylation and acetylation are not discrete and mutually exclusive, but intertwined processes.

Role of signaling in epigenetic control

A final question to ask concerns the role of cell signaling

in influencing the epigenetic processes governing differentiation. Such

a role should exist, as it would be reasonable to think that extrinsic

signaling can lead to epigenetic remodeling, just as it can lead to

changes in gene expression through the activation or repression of

different transcription factors. Little direct data is available

concerning the specific signals that influence the epigenome,

and the majority of current knowledge about the subject consists of

speculations on plausible candidate regulators of epigenetic remodeling.

We will first discuss several major candidates thought to be involved

in the induction and maintenance of both embryonic stem cells and their

differentiated progeny, and then turn to one example of specific

signaling pathways in which more direct evidence exists for its role in

epigenetic change.

The first major candidate is Wnt signaling pathway.

The Wnt pathway is involved in all stages of differentiation, and the

ligand Wnt3a can substitute for the overexpression of c-Myc in the

generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. On the other hand, disruption of ß-catenin, a component of the Wnt signaling pathway, leads to decreased proliferation of neural progenitors.

Growth factors

comprise the second major set of candidates of epigenetic regulators of

cellular differentiation. These morphogens are crucial for development,

and include bone morphogenetic proteins, transforming growth factors (TGFs), and fibroblast growth factors (FGFs). TGFs and FGFs have been shown to sustain expression of OCT4, SOX2, and NANOG by downstream signaling to Smad proteins.

Depletion of growth factors promotes the differentiation of ESCs, while

genes with bivalent chromatin can become either more restrictive or

permissive in their transcription.

Several other signaling pathways are also considered to be primary candidates. Cytokine leukemia inhibitory factors

are associated with the maintenance of mouse ESCs in an

undifferentiated state. This is achieved through its activation of the

Jak-STAT3 pathway, which has been shown to be necessary and sufficient

towards maintaining mouse ESC pluripotency. Retinoic acid can induce differentiation of human and mouse ESCs, and Notch signaling is involved in the proliferation and self-renewal of stem cells. Finally, Sonic hedgehog,

in addition to its role as a morphogen, promotes embryonic stem cell

differentiation and the self-renewal of somatic stem cells.

The problem, of course, is that the candidacy of these signaling

pathways was inferred primarily on the basis of their role in

development and cellular differentiation. While epigenetic regulation is

necessary for driving cellular differentiation, they are certainly not

sufficient for this process. Direct modulation of gene expression

through modification of transcription factors plays a key role that must

be distinguished from heritable epigenetic changes that can persist

even in the absence of the original environmental signals. Only a few

examples of signaling pathways leading to epigenetic changes that alter

cell fate currently exist, and we will focus on one of them.

Expression of Shh (Sonic hedgehog) upregulates the production of BMI1, a component of the PcG complex that recognizes H3K27me3. This occurs in a Gli-dependent manner, as Gli1 and Gli2 are downstream effectors of the Hedgehog signaling pathway. In culture, Bmi1 mediates the Hedgehog pathway's ability to promote human mammary stem cell self-renewal.

In both humans and mice, researchers showed Bmi1 to be highly expressed

in proliferating immature cerebellar granule cell precursors. When Bmi1

was knocked out in mice, impaired cerebellar development resulted,

leading to significant reductions in postnatal brain mass along with

abnormalities in motor control and behavior.

A separate study showed a significant decrease in neural stem cell

proliferation along with increased astrocyte proliferation in Bmi null

mice.

A alternative model of cellular differentiation during

embryogenesis is that positional information is based on mechanical

signalling by the cytoskeleton using Embryonic differentiation waves.

The mechanical signal is then epigenetically transduced via signal

transduction systems (of which specific molecules such as Wnt are part)

to result in differential gene expression.

In summary, the role of signaling in the epigenetic control of

cell fate in mammals is largely unknown, but distinct examples exist

that indicate the likely existence of further such mechanisms.

Effect of matrix elasticity

In

order to fulfill the purpose of regenerating a variety of tissues,

adult stems are known to migrate from their niches, adhere to new

extracellular matrices (ECM) and differentiate. The ductility of these

microenvironments are unique to different tissue types. The ECM

surrounding brain, muscle and bone tissues range from soft to stiff. The

transduction of the stem cells into these cells types is not directed

solely by chemokine cues and cell to cell signaling. The elasticity of

the microenvironment can also affect the differentiation of mesenchymal

stem cells (MSCs which originate in bone marrow.) When MSCs are placed

on substrates of the same stiffness as brain, muscle and bone ECM, the

MSCs take on properties of those respective cell types.

Matrix sensing requires the cell to pull against the matrix at focal

adhesions, which triggers a cellular mechano-transducer to generate a

signal to be informed what force is needed to deform the matrix. To

determine the key players in matrix-elasticity-driven lineage

specification in MSCs, different matrix microenvironments were mimicked.

From these experiments, it was concluded that focal adhesions of the

MSCs were the cellular mechano-transducer sensing the differences of the

matrix elasticity. The non-muscle myosin IIa-c isoforms generates the

forces in the cell that lead to signaling of early commitment markers.

Nonmuscle myosin IIa generates the least force increasing to non-muscle

myosin IIc. There are also factors in the cell that inhibit non-muscle

myosin II, such as blebbistatin. This makes the cell effectively blind

to the surrounding matrix.

Researchers have obtained some success in inducing stem cell-like

properties in HEK 239 cells by providing a soft matrix without the use

of diffusing factors.

The stem-cell properties appear to be linked to tension in the cells'

actin network. One identified mechanism for matrix-induced

differentiation is tension-induced proteins, which remodel chromatin in

response to mechanical stretch. The RhoA pathway is also implicated in this process.