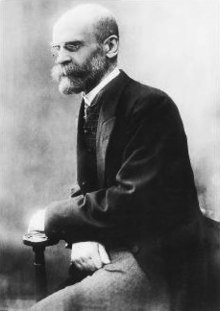

Émile Durkheim

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

David Émile Durkheim

15 April 1858 |

| Died | 15 November 1917 (aged 59) |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure |

| Known for | Sacred–profane dichotomy Collective consciousness Social fact Social integration Anomie Collective effervescence |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Philosophy, sociology, education, anthropology, religious studies |

| Institutions | University of Paris, University of Bordeaux |

| Influences | Immanuel Kant, René Descartes, Plato, Herbert Spencer, Aristotle, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Auguste Comte. William James, John Dewey, Fustel de Coulanges, Jean-Marie Guyau, Charles Bernard Renouvier, John Stuart Mill |

| Influenced | Marcel Mauss, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Talcott Parsons, Maurice Halbwachs, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, Bronisław Malinowski, Fernand Braudel, Pierre Bourdieu, Charles Taylor, Henri Bergson, Emmanuel Levinas, Steven Lukes, Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, E. E. Evans-Pritchard, Mary Douglas, Paul Fauconnet, Robert N. Bellah, Ziya Gökalp, David Bloor, Randall Collins |

David Émile Durkheim was a French sociologist. He formally established the academic discipline and—with W. E. B. Du Bois, Karl Marx and Max Weber—is commonly cited as the principal architect of modern social science.

Much of Durkheim's work was concerned with how societies could maintain their integrity and coherence in modernity, an era in which traditional social and religious ties are no longer assumed, and in which new social institutions have come into being. His first major sociological work was The Division of Labour in Society (1893). In 1895, he published The Rules of Sociological Method and set up the first European department of sociology, becoming France's first professor of sociology. In 1898, he established the journal L'Année Sociologique. Durkheim's seminal monograph, Suicide (1897), a study of suicide rates in Catholic and Protestant populations, pioneered modern social research and served to distinguish social science from psychology and political philosophy. The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912) presented a theory of religion, comparing the social and cultural lives of aboriginal and modern societies.

Durkheim was also deeply preoccupied with the acceptance of sociology as a legitimate science. He refined the positivism originally set forth by Auguste Comte, promoting what could be considered as a form of epistemological realism, as well as the use of the hypothetico-deductive model in social science. For him, sociology was the science of institutions, if this term is understood in its broader meaning as "beliefs and modes of behaviour instituted by the collectivity" and its aim being to discover structural social facts. Durkheim was a major proponent of structural functionalism, a foundational perspective in both sociology and anthropology. In his view, social science should be purely holistic; that is, sociology should study phenomena attributed to society at large, rather than being limited to the specific actions of individuals.

He remained a dominant force in French intellectual life until his death in 1917, presenting numerous lectures and published works on a variety of topics, including the sociology of knowledge, morality, social stratification, religion, law, education, and deviance. Durkheimian terms such as "collective consciousness" have since entered the popular lexicon.

Biography

Childhood and education

Emile Durkheim was born in Épinal in Lorraine, the son of Mélanie (Isidor) and Moïse Durkheim. He came from a long line of devout French Jews; his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had been rabbis.

He began his education in a rabbinical school, but at an early age, he

decided not to follow in his family's footsteps and switched schools.

Durkheim led a completely secular life. Much of his work was dedicated

to demonstrating that religious phenomena stemmed from social rather

than divine factors. While Durkheim chose not to follow in the family

tradition, he did not sever ties with his family or with the Jewish

community. Many of his most prominent collaborators and students were Jewish, and some were blood relations. Marcel Mauss, a notable social anthropologist of the pre-war era, was his nephew. One of his nieces was Claudette (née Raphael) Bloch, a marine biologist and mother of Maurice Bloch, who became a noted anthropologist.

A precocious student, Durkheim entered the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in 1879, at his third attempt. The entering class that year was one of the most brilliant of the nineteenth century and many of his classmates, such as Jean Jaurès and Henri Bergson, would go on to become major figures in France's intellectual history. At the ENS, Durkheim studied under the direction of Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, a classicist with a social scientific outlook, and wrote his Latin dissertation on Montesquieu. At the same time, he read Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer. Thus Durkheim became interested in a scientific approach to society very early on in his career. This meant the first of many conflicts with the French academic system, which had no social science curriculum at the time. Durkheim found humanistic studies uninteresting, turning his attention from psychology and philosophy to ethics and eventually, sociology. He obtained his agrégation in philosophy in 1882, though finishing next to last in his graduating class owing to serious illness the year before.

The opportunity for Durkheim to receive a major academic

appointment in Paris was inhibited by his approach to society. From 1882

to 1887 he taught philosophy at several provincial schools. In 1885 he decided to leave for Germany, where for two years he studied sociology at the universities of Marburg, Berlin and Leipzig. As Durkheim indicated in several essays, it was in Leipzig that he learned to appreciate the value of empiricism and its language of concrete, complex things, in sharp contrast to the more abstract, clear and simple ideas of the Cartesian method. By 1886, as part of his doctoral dissertation, he had completed the draft of his The Division of Labour in Society, and was working towards establishing the new science of sociology.

Academic career

A collection of Durkheim's courses on the origins of socialism (1896), edited and published by his nephew, Marcel Mauss, in 1928

Durkheim's period in Germany resulted in the publication of numerous

articles on German social science and philosophy; Durkheim was

particularly impressed by the work of Wilhelm Wundt. Durkheim's articles gained recognition in France, and he received a teaching appointment in the University of Bordeaux in 1887, where he was to teach the university's first social science course. His official title was Chargé d'un Cours de Science Sociale et de Pédagogie and thus he taught both pedagogy and sociology (the latter had never been taught in France before).

The appointment of the social scientist to the mostly humanistic

faculty was an important sign of the change of times, and also the

growing importance and recognition of the social sciences. From this position Durkheim helped reform the French school system

and introduced the study of social science in its curriculum. However,

his controversial beliefs that religion and morality could be explained

in terms purely of social interaction earned him many critics.

Also in 1887, Durkheim married Louise Dreyfus. They would have two children, Marie and André.

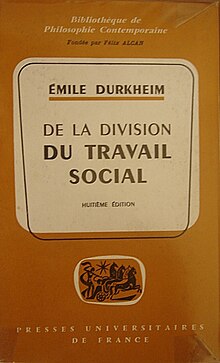

The 1890s were a period of remarkable creative output for Durkheim. In 1893, he published The Division of Labour in Society, his doctoral dissertation and fundamental statement of the nature of human society and its development. Durkheim's interest in social phenomena was spurred on by politics. France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War led to the fall of the regime of Napoleon III, which was then replaced by the Third Republic. This in turn resulted in a backlash against the new secular and republican rule, as many people considered a vigorously nationalistic

approach necessary to rejuvenate France's fading power. Durkheim, a Jew

and a staunch supporter of the Third Republic with a sympathy towards

socialism, was thus in the political minority, a situation that

galvanized him politically. The Dreyfus affair of 1894 only strengthened his activist stance.

In 1895, he published The Rules of Sociological Method, a manifesto stating what sociology is and how it ought to be done, and founded the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux. In 1898, he founded L'Année Sociologique, the first French social science journal.

Its aim was to publish and publicize the work of what was, by then, a

growing number of students and collaborators (this is also the name used

to refer to the group of students who developed his sociological

program). In 1897, he published Suicide, a case study that provided an example of what the sociological monograph might look like. Durkheim was one of the pioneers of the use of quantitative methods in criminology during his suicide case study.

By 1902, Durkheim had finally achieved his goal of attaining a prominent position in Paris when he became the chair of education at the Sorbonne.

Durkheim aimed for the Parisian position earlier, but the Parisian

faculty took longer to accept what some called "sociological

imperialism" and admit social science to their curriculum.

He became a full professor (Professor of the Science of Education)

there in 1906, and in 1913 he was named Chair in "Education and

Sociology". Because French universities

are technically institutions for training secondary school teachers,

this position gave Durkheim considerable influence—his lectures were the

only ones that were mandatory for the entire student body. Durkheim had

much influence over the new generation of teachers; around that time he

also served as an advisor to the Ministry of Education. In 1912, he published his last major work, The Elementary Forms of The Religious Life.

Death

Émile Durkheim's grave in Montparnasse Cemetery

The outbreak of World War I was to have a tragic effect on Durkheim's life. His leftism

was always patriotic rather than internationalist—he sought a secular,

rational form of French life. But the coming of the war and the

inevitable nationalist propaganda

that followed made it difficult to sustain this already nuanced

position. While Durkheim actively worked to support his country in the

war, his reluctance to give in to simplistic nationalist fervor

(combined with his Jewish background) made him a natural target of the

now-ascendant French Right.

Even more seriously, the generations of students that Durkheim had

trained were now being drafted to serve in the army, and many of them

perished in the trenches. Finally, Durkheim's own son, André, died on

the war front in December 1915—a loss from which Durkheim never

recovered. Emotionally devastated, Durkheim collapsed of a stroke in Paris on November 15, 1917. He was buried at the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.

Durkheim's thought

Throughout

his career, Durkheim was concerned primarily with three goals. First,

to establish sociology as a new academic discipline.

Second, to analyse how societies could maintain their integrity and

coherence in the modern era, when things such as shared religious and

ethnic background could no longer be assumed; to that end he wrote much

about the effect of laws, religion, education and similar forces on

society and social integration. Lastly, Durkheim was concerned with the practical implications of scientific knowledge. The importance of social integration is expressed throughout Durkheim's work:

For if society lacks the unity that derives from the fact that the relationships between its parts are exactly regulated, that unity resulting from the harmonious articulation of its various functions assured by effective discipline and if, in addition, society lacks the unity based upon the commitment of men's wills to a common objective, then it is no more than a pile of sand that the least jolt or the slightest puff will suffice to scatter.

— Émile Durkheim

Inspirations

During his university studies at the École, Durkheim was influenced by two neo-Kantian scholars, Charles Bernard Renouvier and Émile Boutroux. The principles Durkheim absorbed from them included rationalism, scientific study of morality, anti-utilitarianism and secular education. His methodology was influenced by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, a supporter of the scientific method.

A fundamental influence on Durkheim's thought was the sociological positivism of Auguste Comte, who effectively sought to extend and apply the scientific method found in the natural sciences to the social sciences. According to Comte, a true social science should stress for empirical facts, as well as induce general scientific laws

from the relationship among these facts. There were many points on

which Durkheim agreed with the positivist thesis. First, he accepted

that the study of society was to be founded on an examination of facts.

Second, like Comte, he acknowledged that the only valid guide to

objective knowledge was the scientific method. Third, he agreed with

Comte that the social sciences could become scientific only when they

were stripped of their metaphysical abstractions and philosophical speculation. At the same time, Durkheim believed that Comte was still too philosophical in his outlook.

A second influence on Durkheim's view of society beyond Comte's positivism was the epistemological outlook called social realism.

Although he never explicitly exposed it, Durkheim adopted a realist

perspective in order to demonstrate the existence of social realities

outside the individual and to show that these realities existed in the

form of the objective relations of society.

As an epistemology of science, realism can be defined as a perspective

that takes as its central point of departure the view that external

social realities exist in the outer world and that these realities are

independent of the individual's perception of them. This view opposes other predominant philosophical perspectives such as empiricism and positivism. Empiricists such as David Hume

had argued that all realities in the outside world are products of

human sense perception. According to empiricists, all realities are thus

merely perceived: they do not exist independently of our perceptions,

and have no causal power in themselves.

Comte's positivism went a step further by claiming that scientific laws

could be deduced from empirical observations. Going beyond this,

Durkheim claimed that sociology would not only discover "apparent" laws,

but would be able to discover the inherent nature of society.

Scholars also debate the exact influence of Jewish thought on

Durkheim's work. The answer remains uncertain; some scholars have argued

that Durkheim's thought is a form of secularized Jewish thought,

while others argue that proving the existence of a direct influence of

Jewish thought on Durkheim's achievements is difficult or impossible.

Establishing sociology

Durkheim authored some of the most programmatic statements on what sociology is and how it should be practiced. His concern was to establish sociology as a science. Arguing for a place for sociology among other sciences he wrote:

Sociology is, then, not an auxiliary of any other science; it is itself a distinct and autonomous science.

To give sociology a place in the academic world and to ensure that it

is a legitimate science, it must have an object that is clear and

distinct from philosophy or psychology, and its own methodology.

He argued, "There is in every society a certain group of phenomena

which may be differentiated from ....those studied by the other natural

sciences."

A fundamental aim of sociology is to discover structural "social facts".

Establishment of sociology as an independent, recognized academic

discipline is amongst Durkheim's largest and most lasting legacies. Within sociology, his work has significantly influenced structuralism or structural functionalism. Scholars inspired by Durkheim include Marcel Mauss, Maurice Halbwachs, Célestin Bouglé, Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, Talcott Parsons, Robert K. Merton, Jean Piaget, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Ferdinand de Saussure, Michel Foucault, Clifford Geertz, Peter Berger, Robert N. Bellah, social reformer Patrick Hunout and others.

Methodology

Cover of the French edition of The Rules of Sociological Method (1919)

In The Rules of Sociological Method (1895), Durkheim expressed his will to establish a method that would guarantee sociology's truly scientific character. One of the questions raised by the author concerns the objectivity

of the sociologist: how may one study an object that, from the very

beginning, conditions and relates to the observer? According to

Durkheim, observation

must be as impartial and impersonal as possible, even though a

"perfectly objective observation" in this sense may never be attained. A

social fact must always be studied according to its relation with other social facts, never according to the individual who studies it. Sociology should therefore privilege comparison rather than the study of singular independent facts.

Durkheim sought to create one of the first rigorous scientific approaches to social phenomena. Along with Herbert Spencer,

he was one of the first people to explain the existence and quality of

different parts of a society by reference to what function they served

in maintaining the quotidian (i.e. by how they make society "work"). He

also agreed with Spencer's organic analogy, comparing society to a living organism. Thus his work is sometimes seen as a precursor to functionalism. Durkheim also insisted that society was more than the sum of its parts.

Unlike his contemporaries Ferdinand Tönnies and Max Weber, he did not focus on what motivates the actions of individuals (an approach associated with methodological individualism), but rather on the study of social facts.

Social facts

A social fact is every way of acting, fixed or not, capable of exercising on the individual an external constraint; or again, every way of acting which is general throughout a given society, while at the same time existing in its own right independent of its individual manifestations.

— Émile Durkheim, The Rules of Sociological Method

Durkheim's work revolved around the study of social facts, a term he

coined to describe phenomena that have an existence in and of

themselves, are not bound to the actions of individuals, but have a

coercive influence upon them. Durkheim argued that social facts have, sui generis, an independent existence greater and more objective than the actions of the individuals that compose society. Only such social facts can explain the observed social phenomena. Being exterior to the individual person, social facts may thus also exercise coercive power

on the various people composing society, as it can sometimes be

observed in the case of formal laws and regulations, but also in

situations implying the presence of informal rules, such as religious

rituals or family norms. Unlike the facts studied in natural sciences, a "social" fact thus refers to a specific category of phenomena:

The determining cause of a social fact must be sought among the antecedent social facts and not among the states of the individual consciousness.

— Émile Durkheim, The Rules of Sociological Method

Such social facts are endowed with a power of coercion, by reason of which they may control individual behaviors. According to Durkheim, these phenomena cannot be reduced to biological or psychological grounds. Social facts can be material (physical objects) or immaterial (meanings, sentiments, etc.). The latter cannot be seen or touched, but they are external and coercive, and as such, they become real, gain "facticity".

Physical objects can represent both material and immaterial social

facts; for example a flag is a physical social fact that often has

various immaterial social facts (the meaning and importance of the flag)

attached to it.

Many social facts, however, have no material form.

Even the most "individualistic" or "subjective" phenomena, such as

love, freedom or suicide, would be regarded by Durkheim as objective

social facts.

Individuals composing society do not directly cause suicide: suicide,

as a social fact, exists independently in society, and is caused by

other social facts (such as rules governing behavior and group attachment), whether an individual likes it or not. Whether a person "leaves" a society does not alter the fact that this society will still contain

suicides. Suicide, like other immaterial social facts, exists

independently of the will of an individual, cannot be eliminated, and is

as influential – coercive – as physical laws such as gravity.

Sociology's task thus consists of discovering the qualities and

characteristics of such social facts, which can be discovered through a quantitative or experimental approach (Durkheim extensively relied on statistics).

Society, collective consciousness and culture

Cover of the French edition of The Division of Labour in Society

Regarding the society itself, like social institutions in general, Durkheim saw it as a set of social facts.

Even more than "what society is", Durkheim was interested in answering

"how is a society created" and "what holds a society together". In The Division of Labour in Society, Durkheim attempted to answer the question of what holds the society together. He assumes that humans are inherently egoistic, but norms, beliefs and values (collective consciousness) form the moral basis of the society, resulting in social integration. Collective consciousness is of key importance to the society, its requisite function without which the society cannot survive.

Collective consciousness produces the society and holds it together,

and at the same time individuals produce collective consciousness

through their interactions. Through collective consciousness human beings become aware of one another as social beings, not just animals.

The totality of beliefs and sentiments common to the average members of a society forms a determinate system with a life of its own. It can be termed the collective or common consciousness.

— Emile Durkheim

In particular, the emotional part of the collective consciousness overrides our egoism: as we are emotionally bound to culture, we act socially because we recognize it is the responsible, moral way to act. A key to forming society is social interaction, and Durkheim believes that human beings, when in a group, will inevitably act in such a way that a society is formed.

The importance of another key social fact: the culture. Groups, when interacting, create their own culture and attach powerful emotions to it. He was one of the first scholars to consider the question of culture so intensely. Durkheim was interested in cultural diversity, and how the existence of diversity nonetheless fails to destroy a society.

To that, Durkheim answered that any apparent cultural diversity is

overridden by a larger, common, and more generalized cultural system,

and the law.

In a socioevolutionary approach, Durkheim described the evolution of societies from mechanical solidarity to organic solidarity (one rising from mutual need). As the societies become more complex, evolving from mechanical to organic solidarity, the division of labour is counteracting and replacing collective consciousness.

In the simpler societies, people are connected to others due to

personal ties and traditions; in the larger, modern society they are

connected due to increased reliance on others with regard to them

performing their specialized tasks needed for the modern, highly complex

society to survive.

In mechanical solidarity, people are self-sufficient, there is little

integration and thus there is the need for use of force and repression

to keep society together. Also, in such societies, people have much fewer options in life. In organic solidarity, people are much more integrated and interdependent and specialisation and cooperation is extensive. Progress from mechanical to organic solidarity is based first on population growth and increasing population density, second on increasing "morality density" (development of more complex social interactions) and thirdly, on the increasing specialisation in workplace.

One of the ways mechanical and organic societies differ is the function

of law: in mechanical society the law is focused on its punitive

aspect, and aims to reinforce the cohesion of the community, often by

making the punishment public and extreme; whereas in the organic society

the law focuses on repairing the damage done and is more focused on

individuals than the community.

One of the main features of the modern, organic society is the importance, sacredness even, given to the concept – social fact – of the individual.

The individual, rather than the collective, becomes the focus of rights

and responsibilities, the center of public and private rituals holding

the society together – a function once performed by the religion. To stress the importance of this concept, Durkheim talked of the "cult of the individual":

Thus very far from there being the antagonism between the individual and society which is often claimed, moral individualism, the cult of the individual, is in fact the product of society itself. It is society that instituted it and made of man the god whose servant it is.

— Émile Durkheim

Durkheim saw the population density and growth as key factors in the evolution of the societies and advent of modernity. As the number of people in a given area increase, so does the number of interactions, and the society becomes more complex. Growing competition between the more numerous people also leads to further division of labour.

In time, the importance of the state, the law and the individual

increases, while that of the religion and moral solidarity decreases.

In another example of evolution of culture, Durkheim pointed to fashion, although in this case he noted a more cyclical phenomenon. According to Durkheim, fashion serves to differentiate between lower classes and upper classes,

but because lower classes want to look like the upper classes, they

will eventually adapt the upper class fashion, depreciating it, and

forcing the upper class to adopt a new fashion.

Social pathologies and crime

As the society, Durkheim noted there are several possible pathologies that could lead to a breakdown of social integration and disintegration of the society: the two most important ones are anomie and forced division of labour; lesser ones include the lack of coordination and suicide.

By anomie Durkheim means a state when too rapid population growth

reduces the amount of interaction between various groups, which in turn

leads to a breakdown of understanding (norms, values, and so on).[62] By forced division of labour Durkheim means a situation where power holders, driven by their desire for profit (greed), results in people doing the work they are unsuited for. Such people are unhappy, and their desire to change the system can destabilize the society.

Durkheim's views on crime were a departure from conventional

notions. He believed that crime is "bound up with the fundamental

conditions of all social life" and serves a social function.

He stated that crime implies "not only that the way remains open to

necessary changes but that in certain cases it directly prepares these

changes". Examining the trial of Socrates,

he argues that "his crime, namely, the independence of his thought,

rendered a service not only to humanity but to his country" as "it

served to prepare a new morality and faith that the Athenians needed". As such, his crime "was a useful prelude to reforms".

In this sense, he saw crime as being able to release certain social

tensions and so have a cleansing or purging effect in society. He

further stated that "the authority which the moral conscience

enjoys must not be excessive; otherwise, no-one would dare to criticize

it, and it would too easily congeal into an immutable form. To make

progress, individual originality must be able to express itself...[even]

the originality of the criminal... shall also be possible".

Suicide

In Suicide (1897), Durkheim explores the differing suicide rates among Protestants and Catholics, arguing that stronger social control among Catholics results in lower suicide rates. According to Durkheim, Catholic society has normal levels of integration while Protestant society has low levels. Overall, Durkheim treated suicide as a social fact,

explaining variations in its rate on a macro level, considering

society-scale phenomena such as lack of connections between people

(group attachment) and lack of regulations of behavior, rather than

individuals' feelings and motivations.

Durkheim believed there was more to suicide than extremely

personal individual life circumstances: for example, a loss of a job,

divorce, or bankruptcy. Instead, he took suicide and explained it as a

social fact instead of a result of one's circumstances. Durkheim

believed that suicide was an instance of social deviance. Social

deviance being any transgression of socially established norms. He

created a normative theory of suicide focusing on the conditions of

group life. The four different types of suicide that he proposed are

egoistic, altruistic, anomic, and fatalistic. He began by plotting

social regulation on the x-axis of his chart, and social integration on

the y-axis. Egoistic suicide corresponds to a low level of social

integration. When one is not well integrated into a social group it can

lead to a feeling that he or she has not made a difference in anyone's

lives. On the other hand, too much social integration would be

altruistic suicide. This occurs when a group dominates the life of an

individual to a degree where they feel meaningless to society. Anomic

suicide occurs when one has an insufficient amount of social regulation.

This stems from the sociological term anomie meaning a sense of

aimlessness or despair that arises from the inability to reasonably

expect life to be predictable. Lastly, there is fatalistic suicide,

which results from too much social regulation. An example of this would

be when one follows the same routine day after day. This leads to he or

she believing there is nothing good to look forward to. Durkheim

suggested this was the most popular form of suicide for prisoners.

This study has been extensively discussed by later scholars and

several major criticisms have emerged. First, Durkheim took most of his

data from earlier researchers, notably Adolph Wagner and Henry Morselli,

who were much more careful in generalizing from their own data. Second,

later researchers found that the Protestant–Catholic differences in

suicide seemed to be limited to German-speaking Europe and thus may have always been the spurious reflection of other factors. Durkheim's study of suicide has been criticized as an example of the logical error termed the ecological fallacy. However, diverging views have contested whether Durkheim's work really contained an ecological fallacy. More recent authors such as Berk (2006) have also questioned the micro–macro relations underlying Durkheim's work. Some, such as Inkeles (1959), Johnson (1965), and Gibbs (1968), have claimed that Durkheim's only intent was to explain suicide sociologically within a holistic perspective, emphasizing that "he intended his theory to explain variation among social environments in the incidence of suicide, not the suicides of particular individuals".

Despite its limitations, Durkheim's work on suicide has influenced proponents of control theory, and is often mentioned as a classic sociological study. The book pioneered modern social research and served to distinguish social science from psychology and political philosophy.

Religion

In The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life,

Durkheim's first purpose was to identify the social origin and function

of religion as he felt that religion was a source of camaraderie and

solidarity.

His second purpose was to identify links between certain religions in

different cultures, finding a common denominator. He wanted to

understand the empirical, social aspect of religion that is common to

all religions and goes beyond the concepts of spirituality and God.

Durkheim defined religion as

A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, i.e., things set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite in one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them.

— Émile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, Book 1, Ch. 1

In this definition, Durkheim avoids references to supernatural or God.

Durkheim argued that the concept of supernatural is relatively new,

tied to the development of science and separation of supernatural—that

which cannot be rationally explained—from natural, that which can. Thus, according to Durkheim, for early humans, everything was supernatural. Similarly, he points out that religions that give little importance to the concept of god exist, such as Buddhism, where the Four Noble Truths are much more important than any individual deity. With that, Durkheim argues, we are left with the following three concepts: the sacred (the ideas that cannot be properly explained, inspire awe and are considered worthy of spiritual respect or devotion), the beliefs and practices (which create highly emotional state—collective effervescence—and invest symbols with sacred importance), and the moral community (a group of people sharing a common moral philosophy). Out of those three concepts, Durkheim focused on the sacred, noting that it is at the very core of a religion. He defined sacred things as:

...simply collective ideals that have fixed themselves on material objects... they are only collective forces hypostasized, that is to say, moral forces; they are made up of the ideas and sentiments awakened in us by the spectacle of society, and not of sensations coming from the physical world.

— Émile Durkheim

Durkheim saw religion as the most fundamental social institution of humankind, and one that gave rise to other social forms. It was the religion that gave humanity the strongest sense of collective consciousness. Durkheim saw the religion as a force that emerged in the early hunter and gatherer

societies, as the emotions collective effervescence run high in the

growing groups, forcing them to act in a new ways, and giving them a

sense of some hidden force driving them.

Over time, as emotions became symbolized and interactions ritualized,

religion became more organized, giving a rise to the division between

the sacred and the profane. However, Durkheim also believed that religion was becoming less important, as it was being gradually superseded by science and the cult of an individual.

Thus there is something eternal in religion that is destined to outlive the succession of particular symbols in which religious thought has clothed itself.

— Émile Durkheim

However, even if the religion was losing its importance for Durkheim,

it still laid the foundation of modern society and the interactions

that governed it.

And despite the advent of alternative forces, Durkheim argued that no

replacement for the force of religion had yet been created. He expressed

his doubt about modernity, seeing the modern times as "a period of

transition and moral mediocrity".

Durkheim also argued that our primary categories for understanding the world have their origins in religion. It is religion, Durkheim writes, that gave rise to most if not all other social constructs, including the larger society. Durkheim argued that categories are produced by the society, and thus are collective creations.

Thus as people create societies, they also create categories, but at

the same time, they do so unconsciously, and the categories are prior to

any individual's experience. In this way Durkheim attempted to bridge the divide between seeing categories as constructed out of human experience and as logically prior to that experience. Our understanding of the world is shaped by social facts; for example the notion of time is defined by being measured through a calendar,

which in turn was created to allow us to keep track of our social

gatherings and rituals; those in turn on their most basic level

originated from religion. In the end, even the most logical and rational pursuit of science can trace its origins to religion. Durkheim states that, "Religion gave birth to all that is essential in the society.

In his work, Durkheim focused on totemism, the religion of the aboriginal Australians and Native Americans.

Durkheim saw totemism as the most ancient religion, and focused on it

as he believed its simplicity would ease the discussion of the essential

elements of religion.

Now the totem is the flag of the clan. It is therefore natural that the impressions aroused by the clan in individual minds— impressions of dependence and of increased vitality—should fix themselves to the idea of the totem rather than that of the clan : for the clan is too complex a reality to be represented clearly in all its complex unity by such rudimentary intelligences.

— Émile Durkheim,

Durkheim's work on religion was criticized on both empirical and

theoretical grounds by specialists in the field. The most important

critique came from Durkheim's contemporary, Arnold van Gennep,

an expert on religion and ritual, and also on Australian belief

systems. Van Gennep argued that Durkheim's views of primitive peoples

and simple societies were "entirely erroneous". Van Gennep further

argued that Durkheim demonstrated a lack of critical stance towards his

sources, collected by traders and priests, naively accepting their

veracity, and that Durkheim interpreted freely from dubious data. At the

conceptual level, van Gennep pointed out Durkheim's tendency to press

ethnography into a prefabricated theoretical scheme.

Despite such critiques, Durkheim's work on religion has been

widely praised for its theoretical insight and whose arguments and

propositions, according to Robert Alun Jones, "have stimulated the

interest and excitement of several generations of sociologists

irrespective of theoretical 'school' or field of specialization".

Sociology and philosophy

Sociology of knowledge

While Durkheim's work deals with a number of subjects, including suicide, the family, social structures, and social institutions, a large part of his work deals with the sociology of knowledge.

While publishing short articles on the subject earlier in his career (for example the essay De quelques formes primitives de classification written in 1902 with Marcel Mauss), Durkheim's definitive statement concerning the sociology of knowledge comes in his 1912 magnum opus The Elementary Forms of Religious Life.

This book has as its goal not only the elucidation of the social

origins and function of religion, but also the social origins and impact

of society on language and logical thought. Durkheim worked largely out

of a Kantian framework and sought to understand how the concepts and

categories of logical thought could arise out of social life. He argued,

for example, that the categories of space and time were not a priori.

Rather, the category of space depends on a society's social grouping

and geographical use of space, and a group's social rhythm that

determines our understanding of time. In this Durkheim sought to combine elements of rationalism and empiricism,

arguing that certain aspects of logical thought common to all humans

did exist, but that they were products of collective life (thus

contradicting the tabla rasa empiricist understanding whereby categories

are acquired by individual experience alone), and that they were not

universal a priori's (as Kant argued) since the content of the categories differed from society to society.

Another key elements to Durkheim's theory of knowledge is his concept of représentations collectives (collective representations), which is outlined in The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Représentations collectives

are the symbols and images that come to represent the ideas, beliefs,

and values elaborated by a collectivity and are not reducible to

individual constituents. They can include words, slogans, ideas, or any

number of material items that can serve as a symbol, such as a cross, a

rock, a temple, a feather etc. As Durkheim elaborates, représentations collectives

are created through intense social interaction and are products of

collective activity. As such these representations have the particular,

and somewhat contradictory, aspect that they exist externally to the

individual (since they are created and controlled not by the individual

but by society as a whole), and yet simultaneously within each

individual of the society (by virtue of that individual's participation

within society).

Arguably the most important "représentation collective" is language,

which according to Durkheim is a product of collective action. And

because language is a collective action, language contains within it a

history of accumulated knowledge and experience that no individual would

be capable of creating on their own. As Durkheim says, 'représentations

collectives', and language in particular:

... add to that which we can learn by our own personal experience all that wisdom and science which the group has accumulated in the course of centuries. Thinking by concepts, is not merely seeing reality on its most general side, but it is projecting a light upon the sensation which illuminates it, penetrates it and transforms it.

As such, language, as a social product, literally structures and

shapes our experience of reality. This discursive approach to language

and society would be developed by later French philosophers, such as Michel Foucault.

Morality

Durkheim defines morality as "a system of rules for conduct". His analysis of morality is strongly marked by Immanuel Kant

and his notion of duty. While Durkheim was influenced by Kant, he was

highly critical of aspects of the latter's moral theory and developed

his own positions.

Durkheim agrees with Kant that within morality, there is an

element of obligation, "a moral authority which, by manifesting itself

in certain precepts particularly important to it, confers upon [moral

rules] an obligatory character".

Morality tells us how to act from a position of superiority. There

exists a certain, pre-established moral norm to which we must conform.

It is through this view that Durkheim makes a first critique of Kant in

saying that moral duties originate in society, and are not to be found

in some universal moral concept such as the categorical imperative.

Durkheim also argues that morality is characterized not just by this

obligation, but is also something that is desired by the individual. The

individual believes that by adhering to morality, they are serving the

common Good, and for this reason, the individual submits voluntarily to the moral commandment.

However, in order to accomplish its aims, morality must be

legitimate in the eyes of those to whom it speaks. As Durkheim argues,

this moral authority is primarily to be located in religion, which is

why in any religion one finds a code of morality. For Durkheim, it is

only society that has the resources, the respect, and the power to

cultivate within an individual both the obligatory and the desirous

aspects of morality.

Deviance

How many times, indeed, it [crime] is only an anticipation of future morality - a step toward what will be! — Émile Durkheim, 'Division of Labour in Society',

Durkheim thought that deviance was an essential component of a functional society.

He believed that deviance had three possible effects on society. First,

Durkheim thought that deviance could challenge the perspective and

thoughts of the general population, leading to social change by pointing

out a flaw in society. Secondly, deviant acts could also support existing social norms and beliefs by evoking the population to discipline the actors.

Finally, Durkheim believed that reactions to deviant activity could

increase camaraderie and social support among the population affected by

the activity. Durkheim's thoughts on deviance contributed to Robert Merton's Strain Theory

Influences and legacy

Durkheim

had an important impact on the development of Anthropology and

Sociology, influencing thinkers from his school of sociology, such as Marcel Mauss, but also later thinkers, such as Maurice Halbwachs, Talcott Parsons, Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, and Claude Lévi-Strauss. More recently, Durkheim has influenced sociologists such as Steven Lukes, Robert N. Bellah, and Pierre Bourdieu. His description of collective consciousness also deeply influenced the Turkish nationalism of Ziya Gökalp, the founding father of Turkish sociology.[96] Randall Collins has developed a theory of what he calls interaction ritual chains, which is a synthesis of Durkheim's work on religion with Erving Goffman's micro-sociology. Goffman himself was also deeply influenced by Durkheim in his development of the interaction order.

Outside of sociology, he influenced philosophers Henri Bergson and Emmanuel Levinas, and his ideas can be found latently in the work of certain structuralist thinkers of the 60s, such as Alain Badiou, Louis Althusser, and Michel Foucault.

Durkheim contra Searle

Much of Durkheim's work, however, remains unacknowledged in philosophy, despite its direct relevance. As proof one can look to John Searle, who wrote a book The Construction of Social Reality,

in which he elaborates a theory of social facts and collective

representations that he believed to be a landmark work that would bridge

the gap between analytic and continental philosophy. Neil Gross

however, demonstrates how Searle's views on society are more or less a

reconstitution of Durkheim's theories of social facts, social

institutions, collective representations and the like. Searle's ideas

are thus open to the same criticisms as Durkheim's.

Searle responded by saying that Durkheim's work was worse than he had

originally believed, and, admitting that he had not read much of

Durkheim's work, said that, "Because Durkheim’s account seemed so

impoverished I did not read any further in his work."

Stephen Lukes, however, responded to Searle's response to Gross and

refutes point by point the allegations that Searle makes against

Durkheim, essentially upholding the argument of Gross, that Searle's

work bears great resemblance to that of Durkheim's. Lukes attributes

Searle's miscomprehension of Durkheim's work to the fact that Searle,

quite simply, never read Durkheim.

Gilbert pro Durkheim

A

contemporary philosopher of social phenomena who has offered a

sympathetic close reading of Durkheim's discussion of social facts in

chapter 1 and the prefaces of The Rules of Sociological Method is Margaret Gilbert. In chapter 4, section 2, of her 1989 book On Social Facts

(whose title may represent an homage to Durkheim, alluding to his

"faits sociaux") Gilbert argues that some of his statements that may

seem to be philosophically untenable are important and fruitful.

Selected works

- Montesquieu's contributions to the formation of social science (1892)

- The Division of Labour in Society (1893)

- The Rules of Sociological Method (1895)

- On the Normality of Crime (1895)

- Suicide (1897)

- The Prohibition of Incest and its Origins (1897), published in L'Année Sociologique, vol. 1, pp. 1–70

- Sociology and its Scientific Domain (1900), translation of an Italian text entitled "La sociologia e il suo dominio scientifico"

- Primitive Classification (1903), in collaboration with Marcel Mauss

- The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912)

- Who Wanted War? (1914), in collaboration with Ernest Denis

- Germany Above All (1915)

Published posthumously:

- Education and Sociology (1922)

- Sociology and Philosophy (1924)

- Moral Education (1925)

- Socialism (1928)

- Pragmatism and Sociology (1955)