Accumulation in the atmosphere of greenhouse gases, especially those resulting from humans burning fossil fuels, has been found to be the predominant cause of global warming and climate change.

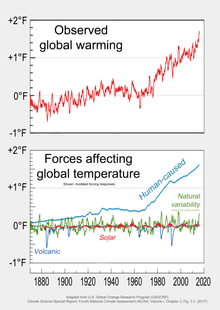

Attribution of recent climate change is the effort to scientifically ascertain mechanisms responsible for recent global warming and related climate changes on Earth. The effort has focused on changes observed during the period of instrumental temperature record, particularly in the last 50 years. This is the period when human activity has grown fastest and observations of the atmosphere above the surface have become available. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), it is "extremely likely" that human influence was the dominant cause of global warming between 1951 and 2010. The best estimate is that observed warming since 1951 has been entirely human caused.

Some of the main human activities that contribute to global warming are:

- increasing atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases, for a warming effect

- global changes to land surface, such as deforestation, for a warming effect

- increasing atmospheric concentrations of aerosols, mainly for a cooling effect

In addition to human activities, some natural mechanisms can also cause climate change, including for example, climate oscillations, changes in solar activity, and volcanic activity.

Multiple lines of evidence support attribution of recent climate change to human activities:

- A physical understanding of the climate system: greenhouse gas concentrations have increased and their warming properties are well-established.

- Historical estimates of past climate changes suggest that the recent changes in global surface temperature are unusual.

- Computer-based climate models are unable to replicate the observed warming unless human greenhouse gas emissions are included.

- Natural forces alone (such as solar and volcanic activity) cannot explain the observed warming.

The IPCC's attribution of recent global warming to human activities is a view shared by the scientific community, and is also supported by 196 other scientific organizations worldwide.

Background

The Keeling Curve shows the long-term increase of atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO

2) concentrations from 1958–2018. Monthly CO

2 measurements display seasonal oscillations in an upward trend. Each year's maximum occurs during the Northern Hemisphere's late spring.

2) concentrations from 1958–2018. Monthly CO

2 measurements display seasonal oscillations in an upward trend. Each year's maximum occurs during the Northern Hemisphere's late spring.

Factors affecting Earth's climate can be broken down into feedbacks and forcings. A forcing is something that is imposed externally on the climate system. External forcings include natural phenomena such as volcanic eruptions and variations in the sun's output. Human activities can also impose forcings, for example, through changing the composition of the atmosphere.

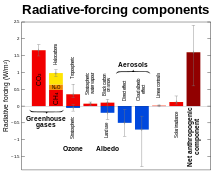

Radiative forcing is a measure of how various factors alter the energy balance of the Earth's atmosphere.

A positive radiative forcing will tend to increase the energy of the

Earth-atmosphere system, leading to a warming of the system. Between the

start of the Industrial Revolution in 1750, and the year 2005, the increase in the atmospheric concentration of carbon dioxide (chemical formula: CO

2) led to a positive radiative forcing, averaged over the Earth's surface area, of about 1.66 watts per square metre (abbreviated W m−2).

2) led to a positive radiative forcing, averaged over the Earth's surface area, of about 1.66 watts per square metre (abbreviated W m−2).

Climate feedbacks can either amplify or dampen the response of the climate to a given forcing.

There are many feedback mechanisms in the climate system that can either amplify (a positive feedback) or diminish (a negative feedback) the effects of a change in climate forcing.

The climate system will vary in response to changes in forcings.

The climate system will show internal variability both in the presence

and absence of forcings imposed on it, (see images opposite). This

internal variability is a result of complex interactions between

components of the climate system, such as the coupling between the atmosphere and ocean (see also the later section on Internal climate variability and global warming). An example of internal variability is the El Niño–Southern Oscillation.

Detection vs. attribution

Probability density function (PDF) of fraction of surface temperature trends since 1950 attributable to human activity, based on IPCC AR5 10.5

In detection and attribution, the natural factors considered usually include changes in the Sun's output and volcanic eruptions, as well as natural modes of variability such as El Niño and La Niña. Human factors include the emissions of heat-trapping "greenhouse" gases and particulates as well as clearing of forests and other land-use changes. Figure source: NOAA NCDC.

Detection and attribution of climate signals, as well as its

common-sense meaning, has a more precise definition within the climate

change literature, as expressed by the IPCC. Detection of a climate signal does not always imply significant attribution. The IPCC's Fourth Assessment Report says "it is extremely likely

that human activities have exerted a substantial net warming influence

on climate since 1750," where "extremely likely" indicates a probability

greater than 95%. Detection of a signal requires demonstrating that an observed change is statistically significantly different from that which can be explained by natural internal variability

.

Attribution requires demonstrating that a signal is:

- unlikely to be due entirely to internal variability;

- consistent with the estimated responses to the given combination of anthropogenic and natural forcing

- not consistent with alternative, physically plausible explanations of recent climate change that exclude important elements of the given combination of forcings.

Key attributions

Greenhouse gases

Carbon dioxide is the primary greenhouse gas that is contributing to recent climate change. CO

2 is absorbed and emitted naturally as part of the carbon cycle, through animal and plant respiration, volcanic eruptions, and ocean-atmosphere exchange. Human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels and changes in land use (see below), release large amounts of carbon to the atmosphere, causing CO

2 concentrations in the atmosphere to rise.

2 is absorbed and emitted naturally as part of the carbon cycle, through animal and plant respiration, volcanic eruptions, and ocean-atmosphere exchange. Human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels and changes in land use (see below), release large amounts of carbon to the atmosphere, causing CO

2 concentrations in the atmosphere to rise.

The high-accuracy measurements of atmospheric CO

2 concentration, initiated by Charles David Keeling in 1958, constitute the master time series documenting the changing composition of the atmosphere. These data have iconic status in climate change science as evidence of the effect of human activities on the chemical composition of the global atmosphere.

2 concentration, initiated by Charles David Keeling in 1958, constitute the master time series documenting the changing composition of the atmosphere. These data have iconic status in climate change science as evidence of the effect of human activities on the chemical composition of the global atmosphere.

In May 2019 the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere reached

415 PPM. The last time when it reached this level was 2.6 - 5.3 million

years ago. Without human intervention, it would be 280 PPM

.

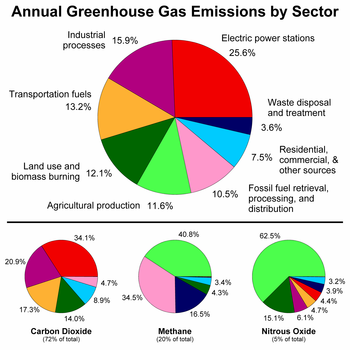

Along with CO

2, methane and to a lesser extent nitrous oxide are also major forcing contributors to the greenhouse effect. The Kyoto Protocol lists these together with hydrofluorocarbon (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), which are entirely artificial gases, as contributors to radiative forcing. The chart at right attributes anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions to eight main economic sectors, of which the largest contributors are power stations (many of which burn coal or other fossil fuels), industrial processes, transportation fuels (generally fossil fuels), and agricultural by-products (mainly methane from enteric fermentation and nitrous oxide from fertilizer use).

2, methane and to a lesser extent nitrous oxide are also major forcing contributors to the greenhouse effect. The Kyoto Protocol lists these together with hydrofluorocarbon (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6), which are entirely artificial gases, as contributors to radiative forcing. The chart at right attributes anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions to eight main economic sectors, of which the largest contributors are power stations (many of which burn coal or other fossil fuels), industrial processes, transportation fuels (generally fossil fuels), and agricultural by-products (mainly methane from enteric fermentation and nitrous oxide from fertilizer use).

Water vapor

Emission Database for Global Atmospheric Research version 4.2, fast track 2010 project

Water vapor is the most abundant greenhouse gas and is the largest

contributor to the natural greenhouse effect, despite having a short

atmospheric lifetime (about 10 days).

Some human activities can influence local water vapor levels. However,

on a global scale, the concentration of water vapor is controlled by

temperature, which influences overall rates of evaporation and precipitation. Therefore, the global concentration of water vapor is not substantially affected by direct human emissions.

Land use

Climate change is attributed to land use for two main reasons. Between 1750 and 2007, about two-thirds of anthropogenic CO

2 emissions were produced from burning fossil fuels, and about one-third of emissions from changes in land use, primarily deforestation. Deforestation both reduces the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by deforested regions and releases greenhouse gases directly, together with aerosols, through biomass burning that frequently accompanies it.

2 emissions were produced from burning fossil fuels, and about one-third of emissions from changes in land use, primarily deforestation. Deforestation both reduces the amount of carbon dioxide absorbed by deforested regions and releases greenhouse gases directly, together with aerosols, through biomass burning that frequently accompanies it.

Some of the causes of climate change are, generally, not

connected with it directly in the media coverage. For example, the harm

done by humans to the populations of Elephants and Monkeys contributes to deforestation therefore to climate change.

A second reason that climate change has been attributed to land use is that the terrestrial albedo is often altered by use, which leads to radiative forcing. This effect is more significant locally than globally.

Livestock and land use

Worldwide, livestock production occupies 70% of all land used for agriculture, or 30% of the ice-free land surface of the Earth.

More than 18% of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions are attributed

to livestock and livestock-related activities such as deforestation and

increasingly fuel-intensive farming practices. Specific attributions to the livestock sector include:

- 9% of global anthropogenic carbon dioxide emissions

- 35–40% of global anthropogenic methane emissions (chiefly due to enteric fermentation and manure)

- 64% of global anthropogenic nitrous oxide emissions, chiefly due to fertilizer use.[29]

Aerosols

With virtual certainty, scientific consensus has attributed various forms of climate change, chiefly cooling effects, to aerosols, which are small particles or droplets suspended in the atmosphere.

Key sources to which anthropogenic aerosols are attributed include:

- biomass burning such as slash-and-burn deforestation. Aerosols produced are primarily black carbon.

- industrial air pollution, which produces soot and airborne sulfates, nitrates, and ammonium

- dust produced by land use effects such as desertification

Attribution of 20th century climate change

One global climate model's

reconstruction of temperature change during the 20th century as the

result of five studied forcing factors and the amount of temperature

change attributed to each.

Over the past 150 years human activities have released increasing quantities of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. This has led to increases in mean global temperature, or global warming. Other human effects are relevant—for example, sulphate aerosols are believed to have a cooling effect. Natural factors also contribute. According to the historical temperature record of the last century, the Earth's near-surface air temperature has risen around 0.74 ± 0.18 °Celsius (1.3 ± 0.32 °Fahrenheit).

A historically important question in climate change research has regarded the relative importance of human activity and non-anthropogenic causes during the period of instrumental record. In the 1995 Second Assessment Report (SAR), the IPCC

made the widely quoted statement that "The balance of evidence suggests

a discernible human influence on global climate". The phrase "balance

of evidence" suggested the (English) common-law standard of proof

required in civil as opposed to criminal courts: not as high as "beyond

reasonable doubt". In 2001 the Third Assessment Report

(TAR) refined this, saying "There is new and stronger evidence that

most of the warming observed over the last 50 years is attributable to

human activities". The 2007 Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) strengthened this finding:

- "Anthropogenic warming of the climate system is widespread and can be detected in temperature observations taken at the surface, in the free atmosphere and in the oceans. Evidence of the effect of external influences, both anthropogenic and natural, on the climate system has continued to accumulate since the TAR."

Other findings of the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report include:

- "It is extremely unlikely (<5 and="" be="" being="" can="" century="" during="" explained="" external="" forcing="" global="" half="" i.e.="" i="" inconsistent="" internal="" is="" it="" of="" past="" pattern="" result="" that="" the="" variability="" warming="" with="" without="">very unlikely

Over the past five decades there has been a global warming of approximately 0.65 °C (1.17 °F) at the Earth's surface (see historical temperature record).

Among the possible factors that could produce changes in global mean

temperature are internal variability of the climate system, external

forcing, an increase in concentration of greenhouse gases, or any

combination of these. Current studies indicate that the increase in

greenhouse gases, most notably CO

2, is mostly responsible for the observed warming. Evidence for this conclusion includes:

2, is mostly responsible for the observed warming. Evidence for this conclusion includes:

- Estimates of internal variability from climate models, and reconstructions of past temperatures, indicate that the warming is unlikely to be entirely natural.

- Climate models forced by natural factors and increased greenhouse gases and aerosols reproduce the observed global temperature changes; those forced by natural factors alone do not.

- "Fingerprint" methods (see below) indicate that the pattern of change is closer to that expected from greenhouse gas-forced change than from natural change.

- The plateau in warming from the 1940s to 1960s can be attributed largely to sulphate aerosol cooling.

Details on attribution

For

Northern Hemisphere temperature, recent decades appear to be the

warmest since at least about 1000AD, and the warming since the late 19th

century is unprecedented over the last 1000 years. Older data are insufficient to provide reliable hemispheric temperature estimates.

Recent scientific assessments find that most of the warming of the

Earth's surface over the past 50 years has been caused by human

activities.

This conclusion rests on multiple lines of evidence. Like the warming

"signal" that has gradually emerged from the "noise" of natural climate

variability, the scientific evidence for a human influence on global

climate has accumulated over the past several decades, from many

hundreds of studies. No single study is a "smoking gun."

Nor has any single study or combination of studies undermined the large

body of evidence supporting the conclusion that human activity is the

primary driver of recent warming.

The first line of evidence is based on a physical understanding

of how greenhouse gases trap heat, how the climate system responds to

increases in greenhouse gases, and how other human and natural factors

influence climate. The second line of evidence is from indirect

estimates of climate changes over the last 1,000 to 2,000 years. These

records are obtained from living things and their remains (like tree rings and corals) and from physical quantities (like the ratio between lighter and heavier isotopes of oxygen in ice cores),

which change in measurable ways as climate changes. The lesson from

these data is that global surface temperatures over the last several

decades are clearly unusual, in that they were higher than at any time

during at least the past 400 years. For the Northern Hemisphere, the recent temperature rise is clearly unusual in at least the last 1,000 years (see graph opposite).

The third line of evidence is based on the broad, qualitative

consistency between observed changes in climate and the computer model

simulations of how climate would be expected to change in response to

human activities. For example, when climate models are run with

historical increases in greenhouse gases, they show gradual warming of

the Earth and ocean surface, increases in ocean heat content and the

temperature of the lower atmosphere, a rise in global sea level, retreat of sea ice and snow cover, cooling of the stratosphere, an increase in the amount of atmospheric water vapor, and changes in large-scale precipitation and pressure patterns. These and other aspects of modelled climate change are in agreement with observations.

"Fingerprint" studies

Reconstructions

of global temperature that include greenhouse gas increases and other

human influences (red line, based on many models) closely match measured

temperatures (dashed line). Those that only include natural influences (blue line, based on many models) show a slight cooling, which has not occurred.

The ability of models to generate reasonable histories of global

temperature is verified by their response to four 20th-century volcanic

eruptions: each eruption caused brief cooling that appeared in observed

as well as modeled records.

Finally, there is extensive statistical

evidence from so-called "fingerprint" studies. Each factor that affects

climate produces a unique pattern of climate response, much as each

person has a unique fingerprint. Fingerprint studies exploit these

unique signatures, and allow detailed comparisons of modelled and

observed climate change patterns. Scientists rely on such studies to

attribute observed changes in climate to a particular cause or set of

causes. In the real world, the climate changes that have occurred since

the start of the Industrial Revolution

are due to a complex mixture of human and natural causes. The

importance of each individual influence in this mixture changes over

time. Of course, there are not multiple Earths, which would allow an

experimenter to change one factor at a time on each Earth, thus helping

to isolate different fingerprints. Therefore, climate models are used to

study how individual factors affect climate. For example, a single

factor (like greenhouse gases) or a set of factors can be varied, and

the response of the modelled climate system to these individual or

combined changes can thus be studied.

For example, when climate model simulations of the last century

include all of the major influences on climate, both human-induced and

natural, they can reproduce many important features of observed climate

change patterns. When human influences are removed from the model

experiments, results suggest that the surface of the Earth would

actually have cooled slightly over the last 50 years (see graph,

opposite). The clear message from fingerprint studies is that the

observed warming over the last half-century cannot be explained by

natural factors, and is instead caused primarily by human factors.

Another fingerprint of human effects on climate has been

identified by looking at a slice through the layers of the atmosphere,

and studying the pattern of temperature changes from the surface up

through the stratosphere (see the section on solar activity).

The earliest fingerprint work focused on changes in surface and

atmospheric temperature. Scientists then applied fingerprint methods to a

whole range of climate variables, identifying human-caused climate

signals in the heat content of the oceans, the height of the tropopause (the boundary between the troposphere and stratosphere, which has shifted upward by hundreds of feet in recent decades), the geographical patterns of precipitation, drought, surface pressure, and the runoff from major river basins.

Studies published after the appearance of the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report in 2007 have also found human fingerprints in the increased levels of atmospheric moisture (both close to the surface and over the full extent of the atmosphere), in the decline of Arctic sea ice extent, and in the patterns of changes in Arctic and Antarctic surface temperatures.

The message from this entire body of work is that the climate

system is telling a consistent story of increasingly dominant human

influence – the changes in temperature, ice extent, moisture, and circulation patterns fit together in a physically consistent way, like pieces in a complex puzzle.

Increasingly, this type of fingerprint work is shifting its

emphasis. As noted, clear and compelling scientific evidence supports

the case for a pronounced human influence on global climate. Much of the

recent attention is now on climate changes at continental and regional

scales, and on variables that can have large impacts on societies. For

example, scientists have established causal links between human

activities and the changes in snowpack, maximum and minimum (diurnal) temperature, and the seasonal timing of runoff over mountainous regions of the western United States. Human activity is likely to have made a substantial contribution to ocean surface temperature changes in hurricane

formation regions. Researchers are also looking beyond the physical

climate system, and are beginning to tie changes in the distribution and

seasonal behaviour of plant and animal species to human-caused changes

in temperature and precipitation.

For over a decade, one aspect of the climate change story seemed

to show a significant difference between models and observations. In the

tropics,

all models predicted that with a rise in greenhouse gases, the

troposphere would be expected to warm more rapidly than the surface.

Observations from weather balloons, satellites, and surface thermometers

seemed to show the opposite behaviour (more rapid warming of the

surface than the troposphere). This issue was a stumbling block in

understanding the causes of climate change. It is now largely resolved.

Research showed that there were large uncertainties in the satellite and weather balloon

data. When uncertainties in models and observations are properly

accounted for, newer observational data sets (with better treatment of

known problems) are in agreement with climate model results.

This

set of graphs shows the estimated contribution of various natural and

human factors to changes in global mean temperature between 1889–2006. Estimated contributions are based on multivariate analysis rather than model simulations.

The graphs show that human influence on climate has eclipsed the

magnitude of natural temperature changes over the past 120 years.

Natural influences on temperature—El Niño, solar variability, and

volcanic aerosols—have varied approximately plus and minus 0.2 °C

(0.4 °F), (averaging to about zero), while human influences have

contributed roughly 0.8 °C (1 °F) of warming since 1889.

This does not mean, however, that all remaining differences between

models and observations have been resolved. The observed changes in some

climate variables, such as Arctic sea ice, some aspects of

precipitation, and patterns of surface pressure, appear to be proceeding

much more rapidly than models have projected. The reasons for these

differences are not well understood. Nevertheless, the bottom-line

conclusion from climate fingerprinting is that most of the observed

changes studied to date are consistent with each other, and are also

consistent with our scientific understanding of how the climate system

would be expected to respond to the increase in heat-trapping gases

resulting from human activities.

Extreme weather events

Frequency

of occurrence (vertical axis) of local June–July–August temperature

anomalies (relative to 1951–1980 mean) for Northern Hemisphere land in

units of local standard deviation (horizontal axis). According to Hansen et al. (2012),

the distribution of anomalies has shifted to the right as a consequence

of global warming, meaning that unusually hot summers have become more

common. This is analogous to the rolling of a dice: cool summers now

cover only half of one side of a six-sided die, white covers one side,

red covers four sides, and an extremely hot (red-brown) anomaly covers

half of one side.

One of the subjects discussed in the literature is whether or not

extreme weather events can be attributed to human activities.

Seneviratne et al. (2012)

stated that attributing individual extreme weather events to human

activities was challenging. They were, however, more confident over

attributing changes in long-term trends of extreme weather. For example,

Seneviratne et al. (2012)

concluded that human activities had likely led to a warming of extreme

daily minimum and maximum temperatures at the global scale.

Another way of viewing the problem is to consider the effects of

human-induced climate change on the probability of future extreme

weather events. Stott et al. (2003), for example, considered whether or not human activities had increased the risk of severe heat waves in Europe, like the one experienced in 2003. Their conclusion was that human activities had very likely more than doubled the risk of heat waves of this magnitude.

An analogy can be made between an athlete on steroids and human-induced climate change.

In the same way that an athlete's performance may increase from using

steroids, human-induced climate change increases the risk of some

extreme weather events.

Hansen et al. (2012)

suggested that human activities have greatly increased the risk of

summertime heat waves. According to their analysis, the land area of the

Earth affected by very hot summer temperature anomalies has greatly

increased over time. In the base period

1951-1980, these anomalies covered a few tenths of 1% of the global land

area. In recent years, this has increased to around 10% of the global land area. With high confidence, Hansen et al. (2012) attributed the 2010 Moscow and 2011 Texas heat waves to human-induced global warming.

An earlier study by Dole et al. (2011) concluded that the 2010 Moscow heatwave was mostly due to natural weather variability. While not directly citing Dole et al. (2011), Hansen et al. (2012) rejected this type of explanation. Hansen et al. (2012)

stated that a combination of natural weather variability and

human-induced global warming was responsible for the Moscow and Texas

heat waves.

Scientific literature and opinion

There are a number of examples of published and informal support for

the consensus view. As mentioned earlier, the IPCC has concluded that

most of the observed increase in globally averaged temperatures since

the mid-20th century is "very likely" due to human activities. The IPCC's conclusions are consistent with those of several reports produced by the US National Research Council.

A report published in 2009 by the U.S. Global Change Research Program concluded that "[global] warming is unequivocal and primarily human-induced."

A number of scientific organizations have issued statements that support the consensus view. Two examples include:

- a joint statement made in 2005 by the national science academies of the G8, and Brazil, China and India;

- a joint statement made in 2008 by the Network of African Science Academies.

Detection and attribution studies

This image shows three examples of internal climate variability measured between 1950 and 2012: the El Niño–Southern oscillation, the Arctic oscillation, and the North Atlantic oscillation.

The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (2007), concluded that attribution

was possible for a number of observed changes in the climate.

However, attribution was found to be more difficult when assessing

changes over smaller regions (less than continental scale) and over

short time periods (less than 50 years).

Over larger regions, averaging reduces natural variability of the climate, making detection and attribution easier.

- In 1996, in a paper in Nature titled "A search for human influences on the thermal structure of the atmosphere", Benjamin D. Santer et al. wrote: "The observed spatial patterns of temperature change in the free atmosphere from 1963 to 1987 are similar to those predicted by state-of-the-art climate models incorporating various combinations of changes in carbon dioxide, anthropogenic sulphate aerosol and stratospheric ozone concentrations. The degree of pattern similarity between models and observations increases through this period. It is likely that this trend is partially due to human activities, although many uncertainties remain, particularly relating to estimates of natural variability."

- A 2002 paper in the Journal of Geophysical Research says "Our analysis suggests that the early twentieth century warming can best be explained by a combination of warming due to increases in greenhouse gases and natural forcing, some cooling due to other anthropogenic forcings, and a substantial, but not implausible, contribution from internal variability. In the second half of the century we find that the warming is largely caused by changes in greenhouse gases, with changes in sulphates and, perhaps, volcanic aerosol offsetting approximately one third of the warming."

- A 2005 review of detection and attribution studies by the International Ad Hoc Detection and Attribution Group found that "natural drivers such as solar variability and volcanic activity are at most partially responsible for the large-scale temperature changes observed over the past century, and that a large fraction of the warming over the last 50 yr can be attributed to greenhouse gas increases. Thus, the recent research supports and strengthens the IPCC Third Assessment Report conclusion that 'most of the global warming over the past 50 years is likely due to the increase in greenhouse gases.'"

- Barnett and colleagues (2005) say that the observed warming of the oceans "cannot be explained by natural internal climate variability or solar and volcanic forcing, but is well simulated by two anthropogenically forced climate models," concluding that "it is of human origin, a conclusion robust to observational sampling and model differences".

- Two papers in the journal Science in August 2005 resolve the problem, evident at the time of the TAR, of tropospheric temperature trends (see also the section on "fingerprint" studies) . The UAH version of the record contained errors, and there is evidence of spurious cooling trends in the radiosonde record, particularly in the tropics. See satellite temperature measurements for details; and the 2006 US CCSP report.

- Multiple independent reconstructions of the temperature record of the past 1000 years confirm that the late 20th century is probably the warmest period in that time (see the preceding section -details on attribution).

Reviews of scientific opinion

- An essay in Science surveyed 928 abstracts related to climate change, and concluded that most journal reports accepted the consensus. This is discussed further in scientific consensus on climate change.

- A 2010 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences found that among a pool of roughly 1,000 researchers who work directly on climate issues and publish the most frequently on the subject, 97% agree that anthropogenic climate change is happening.

- A 2011 paper from George Mason University published in the International Journal of Public Opinion Research, "The Structure of Scientific Opinion on Climate Change," collected the opinions of scientists in the earth, space, atmospheric, oceanic or hydrological sciences. The 489 survey respondents—representing nearly half of all those eligible according to the survey's specific standards – work in academia, government, and industry, and are members of prominent professional organizations. The study found that 97% of the 489 scientists surveyed agreed that global temperatures have risen over the past century. Moreover, 84% agreed that "human-induced greenhouse warming" is now occurring." Only 5% disagreed with the idea that human activity is a significant cause of global warming.

As described above, a small minority of scientists do disagree with the consensus: see list of scientists opposing global warming consensus. For example, Willie Soon and Richard Lindzen

say that there is insufficient proof for anthropogenic attribution.

Generally this position requires new physical mechanisms to explain the

observed warming.

Solar activity

Solar irradiance (yellow) plotted together with temperature (red) over 1880 to 2018.

Modelled

simulation of the effect of various factors (including GHGs, Solar

irradiance) singly and in combination, showing in particular that solar

activity produces a small and nearly uniform warming, unlike what is

observed.

Solar sunspot maximum occurs when the magnetic field of the sun collapses and reverse as part of its average 11 year solar cycle (22 years for complete North to North restoration).

The role of the sun in recent climate change has been looked at by climate scientists. Since 1978, output from the Sun has been measured by satellites significantly more accurately than was previously possible from the surface. These measurements indicate that the Sun's total solar irradiance

has not increased since 1978, so the warming during the past 30 years

cannot be directly attributed to an increase in total solar energy

reaching the Earth (see graph above, left). In the three decades since

1978, the combination of solar and volcanic activity probably had a slight cooling influence on the climate.

Climate models have been used to examine the role of the sun in recent climate change.

Models are unable to reproduce the rapid warming observed in recent

decades when they only take into account variations in total solar

irradiance and volcanic activity. Models are, however, able to simulate

the observed 20th century changes in temperature when they include all

of the most important external forcings, including human influences and

natural forcings. As has already been stated, Hegerl et al.

(2007) concluded that greenhouse gas forcing had "very likely" caused

most of the observed global warming since the mid-20th century. In

making this conclusion, Hegerl et al. (2007) allowed for the possibility that climate models had been underestimated the effect of solar forcing.

The role of solar activity in climate change has also been calculated over longer time periods using "proxy" datasets, such as tree rings.

Models indicate that solar and volcanic forcings can explain periods of relative warmth and cold between A.D. 1000 and 1900, but human-induced forcings are needed to reproduce the late-20th century warming.

Another line of evidence against the sun having caused recent

climate change comes from looking at how temperatures at different

levels in the Earth's atmosphere have changed.

Models and observations (see figure above, middle) show that greenhouse

gas results in warming of the lower atmosphere at the surface (called

the troposphere) but cooling of the upper atmosphere (called the stratosphere). Depletion of the ozone layer by chemical refrigerants

has also resulted in a cooling effect in the stratosphere. If the sun

was responsible for observed warming, warming of the troposphere at the

surface and warming at the top of the stratosphere would be expected as

increase solar activity would replenish ozone and oxides of nitrogen.

The stratosphere has a reverse temperature gradient than the

troposphere so as the temperature of the troposphere cools with

altitude, the stratosphere rises with altitude. Hadley cells

are the mechanism by which equatorial generated ozone in the tropics

(highest area of UV irradiance in the stratosphere) is moved poleward.

Global climate models suggest that climate change may widen the Hadley

cells and push the jetstream northward thereby expanding the tropics

region and resulting in warmer, dryer conditions in those areas overall.

Non-consensus views

Contribution of natural factors and human activities to radiative forcing of climate change. Radiative forcing values are for the year 2005, relative to the pre-industrial era (1750).

The contribution of solar irradiance to radiative forcing is 5% the

value of the combined radiative forcing due to increases in the

atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide.

Habibullo Abdussamatov (2004), head of space research at St. Petersburg's Pulkovo Astronomical Observatory in Russia, has argued that the sun is responsible for recently observed climate change. Journalists for news sources canada.com (Solomon, 2007b), National Geographic News (Ravillious, 2007), and LiveScience (Than, 2007) reported on the story of warming on Mars.

In these articles, Abdussamatov was quoted. He stated that warming on

Mars was evidence that global warming on Earth was being caused by

changes in the sun.

Ravillious (2007) quoted two scientists who disagreed with Abdussamatov: Amato Evan, a climate scientist at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, in the US, and Colin Wilson, a planetary physicist at Oxford University in the UK. According to Wilson, "Wobbles in the orbit of Mars are the main cause of its climate change in the current era" (see also orbital forcing). Than (2007) quoted Charles Long, a climate physicist at Pacific Northwest National Laboratories in the US, who disagreed with Abdussamatov.

Than (2007) pointed to the view of Benny Peiser, a social anthropologist at Liverpool John Moores University in the UK. In his newsletter, Peiser had cited a blog that had commented on warming observed on several planetary bodies in the Solar system. These included Neptune's moon Triton, Jupiter, Pluto and Mars. In an e-mail interview with Than (2007), Peiser stated that:

"I think it is an intriguing coincidence that warming trends have been observed on a number of very diverse planetary bodies in our solar system, (...) Perhaps this is just a fluke."

Than (2007) provided alternative explanations of why warming had occurred on Triton, Pluto, Jupiter and Mars.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA, 2009) responded to public comments on climate change attribution.

A number of commenters had argued that recent climate change could be

attributed to changes in solar irradiance. According to the US EPA

(2009), this attribution was not supported by the bulk of the scientific literature.

Citing the work of the IPCC (2007), the US EPA pointed to the low

contribution of solar irradiance to radiative forcing since the start of

the Industrial Revolution in 1750. Over this time period (1750 to

2005),

the estimated contribution of solar irradiance to radiative forcing was

5% the value of the combined radiative forcing due to increases in the

atmospheric concentrations of carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide

(see graph opposite).

Effect of cosmic rays

Henrik Svensmark has suggested that the magnetic activity of the sun deflects cosmic rays, and that this may influence the generation of cloud condensation nuclei, and thereby have an effect on the climate. The website ScienceDaily reported on a 2009 study that looked at how past changes in climate have been affected by the Earth's magnetic field.

Geophysicist Mads Faurschou Knudsen, who co-authored the study, stated

that the study's results supported Svensmark's theory. The authors of

the study also acknowledged that CO

2 plays an important role in climate change.

2 plays an important role in climate change.

Consensus view on cosmic rays

The view that cosmic rays could provide the mechanism by which changes

in solar activity affect climate is not supported by the literature. Solomon et al. (2007) state:

[..] the cosmic ray time series does not appear to correspond to global total cloud cover after 1991 or to global low-level cloud cover after 1994. Together with the lack of a proven physical mechanism and the plausibility of other causal factors affecting changes in cloud cover, this makes the association between galactic cosmic ray-induced changes in aerosol and cloud formation controversial

Studies by Lockwood and Fröhlich (2007) and Sloan and Wolfendale (2008) found no relation between warming in recent decades and cosmic rays. Pierce and Adams (2009)

used a model to simulate the effect of cosmic rays on cloud properties.

They concluded that the hypothesized effect of cosmic rays was too

small to explain recent climate change. Pierce and Adams (2009)

noted that their findings did not rule out a possible connection

between cosmic rays and climate change, and recommended further

research.

Erlykin et al. (2009)

found that the evidence showed that connections between solar variation

and climate were more likely to be mediated by direct variation of

insolation rather than cosmic rays, and concluded: "Hence within our

assumptions, the effect of varying solar activity, either by direct

solar irradiance or by varying cosmic ray rates, must be less than 0.07

°C since 1956, i.e. less than 14% of the observed global warming."

Carslaw (2009) and Pittock (2009)

review the recent and historical literature in this field and continue

to find that the link between cosmic rays and climate is tenuous, though

they encourage continued research. US EPA (2009) commented on research by Duplissy et al. (2009):

The CLOUD experiments at CERN are interesting research but do not provide conclusive evidence that cosmic rays can serve as a major source of cloud seeding. Preliminary results from the experiment (Duplissy et al., 2009) suggest that though there was some evidence of ion mediated nucleation, for most of the nucleation events observed the contribution of ion processes appeared to be minor. These experiments also showed the difficulty in maintaining sufficiently clean conditions and stable temperatures to prevent spurious aerosol bursts. There is no indication that the earlier Svensmark experiments could even have matched the controlled conditions of the CERN experiment. We find that the Svensmark results on cloud seeding have not yet been shown to be robust or sufficient to materially alter the conclusions of the assessment literature, especially given the abundance of recent literature that is skeptical of the cosmic ray-climate linkage