From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

Tevatron, a

synchrotron collider type particle accelerator at

Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory

(Fermilab), Batavia, Illinois, USA. Shut down in 2011, until 2007 it

was the most powerful particle accelerator in the world, accelerating

protons to an energy of over 1

TeV

(tera electron volts). Beams of circulating protons in the two circular

vacuum chambers in the two rings visible collided at their intersection

point.

Animation showing the operation of a

linear accelerator, widely used in both physics research and cancer treatment.

A particle accelerator is a machine that uses electromagnetic fields to propel charged particles to very high speeds and energies, and to contain them in well-defined beams.

Large accelerators are used for basic research in particle physics. The largest accelerator currently operating is the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) near Geneva, Switzerland, operated by the CERN. It is a collider accelerator, which can accelerate two beams of protons to an energy of 6.5 TeV and cause them to collide head-on, creating center-of-mass energies of 13 TeV. Other powerful accelerators are, RHIC at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York and, formerly, the Tevatron at Fermilab, Batavia, Illinois. Accelerators are also used as synchrotron light sources for the study of condensed matter physics. Smaller particle accelerators are used in a wide variety of applications, including particle therapy for oncological purposes, radioisotope production for medical diagnostics, ion implanters for manufacture of semiconductors, and accelerator mass spectrometers for measurements of rare isotopes such as radiocarbon. There are currently more than 30,000 accelerators in operation around the world.

There are two basic classes of accelerators: electrostatic and electrodynamic (or electromagnetic) accelerators. Electrostatic accelerators use static electric fields to accelerate particles. The most common types are the Cockcroft–Walton generator and the Van de Graaff generator. A small-scale example of this class is the cathode ray tube in an ordinary old television set. The achievable kinetic energy for particles in these devices is determined by the accelerating voltage, which is limited by electrical breakdown. Electrodynamic or electromagnetic accelerators, on the other hand, use changing electromagnetic fields (either magnetic induction or oscillating radio frequency

fields) to accelerate particles. Since in these types the particles can

pass through the same accelerating field multiple times, the output

energy is not limited by the strength of the accelerating field. This

class, which was first developed in the 1920s, is the basis for most

modern large-scale accelerators.

Rolf Widerøe, Gustav Ising, Leó Szilárd, Max Steenbeck, and Ernest Lawrence are considered pioneers of this field, conceiving and building the first operational linear particle accelerator, the betatron, and the cyclotron.

Because the target of the particle beams of early accelerators

was usually the atoms of a piece of matter, with the goal being to

create collisions with their nuclei in order to investigate nuclear

structure, accelerators were commonly referred to as atom smashers in the 20th century. The term persists despite the fact that many modern accelerators create collisions between two subatomic particles, rather than a particle and an atomic nucleus.

Uses

Building covering the 2 mile (3.2 km) beam tube of the

Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC) at Menlo Park, California, the second most powerful linac in the world.

Beams of high-energy particles are useful for fundamental and applied

research in the sciences, and also in many technical and industrial

fields unrelated to fundamental research. It has been estimated that

there are approximately 30,000 accelerators worldwide. Of these, only

about 1% are research machines with energies above 1 GeV, while about 44% are for radiotherapy, 41% for ion implantation, 9% for industrial processing and research, and 4% for biomedical and other low-energy research.

High-energy physics

For

the most basic inquiries into the dynamics and structure of matter,

space, and time, physicists seek the simplest kinds of interactions at

the highest possible energies. These typically entail particle energies

of many GeV, and interactions of the simplest kinds of particles: leptons (e.g. electrons and positrons) and quarks for the matter, or photons and gluons for the field quanta. Since isolated quarks are experimentally unavailable due to color confinement, the simplest available experiments involve the interactions of, first, leptons with each other, and second, of leptons with nucleons,

which are composed of quarks and gluons. To study the collisions of

quarks with each other, scientists resort to collisions of nucleons,

which at high energy may be usefully considered as essentially 2-body interactions

of the quarks and gluons of which they are composed. This elementary

particle physicists tend to use machines creating beams of electrons,

positrons, protons, and antiprotons, interacting with each other or with the simplest nuclei (e.g., hydrogen or deuterium) at the highest possible energies, generally hundreds of GeV or more.

The largest and highest-energy particle accelerator used for elementary particle physics is the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at CERN, operating since 2009.

Nuclear physics and isotope production

Nuclear physicists and cosmologists may use beams of bare atomic nuclei, stripped of electrons, to investigate the structure, interactions, and properties of the nuclei themselves, and of condensed matter at extremely high temperatures and densities, such as might have occurred in the first moments of the Big Bang. These investigations often involve collisions of heavy nuclei – of atoms like iron or gold – at energies of several GeV per nucleon. The largest such particle accelerator is the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

Particle accelerators can also produce proton beams, which can produce proton-rich medical or research isotopes as opposed to the neutron-rich ones made in fission reactors; however, recent work has shown how to make 99Mo, usually made in reactors, by accelerating isotopes of hydrogen, although this method still requires a reactor to produce tritium. An example of this type of machine is LANSCE at Los Alamos.

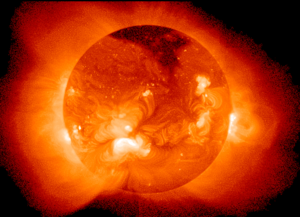

Synchrotron radiation

Electrons propagating through a magnetic field emit very bright and coherent photon beams via synchrotron radiation.

It has numerous uses in the study of atomic structure, chemistry,

condensed matter physics, biology, and technology. A large number of synchrotron light sources exist worldwide. Examples in the U.S. are SSRL at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, APS at Argonne National Laboratory, ALS at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, and NSLS at Brookhaven National Laboratory. In Europe, there are MAX IV in Lund, Sweden, BESSY in Berlin, Germany, Diamond in Oxfordshire, UK, ESRF in Grenoble, France, the latter has been used to extract detailed 3-dimensional images of insects trapped in amber.

Free-electron lasers (FELs) are a special class of light sources based on synchrotron radiation that provides shorter pulses with higher temporal coherence. A specially designed FEL is the most brilliant source of x-rays in the observable universe. The most prominent examples are the LCLS in the U.S. and European XFEL in Germany. More attention is being drawn towards soft x-ray lasers, which together with pulse shortening opens up new methods for attosecond science. Apart from x-rays, FELs are used to emit terahertz light, e.g. FELIX in Nijmegen, Netherlands, TELBE in Dresden, Germany and NovoFEL in Novosibirsk, Russia.

Thus there is a great demand for electron accelerators of moderate (GeV) energy, high intensity and high beam quality to drive light sources.

Low-energy machines and particle therapy

Everyday examples of particle accelerators are cathode ray tubes found in television sets and X-ray generators. These low-energy accelerators use a single pair of electrodes with a DC

voltage of a few thousand volts between them. In an X-ray generator,

the target itself is one of the electrodes. A low-energy particle

accelerator called an ion implanter is used in the manufacture of integrated circuits.

At lower energies, beams of accelerated nuclei are also used in medicine as particle therapy, for the treatment of cancer.

DC accelerator types capable of accelerating particles to speeds sufficient to cause nuclear reactions are Cockcroft-Walton generators or voltage multipliers, which convert AC to high voltage DC, or Van de Graaff generators that use static electricity carried by belts.

Radiation sterilization of medical devices

Electron beam processing is commonly used for sterilization. Electron beams are an on-off technology that provide a much higher dose rate than gamma or X-rays emitted by radioisotopes like cobalt-60 (60Co) or caesium-137 (137Cs). Due to the higher dose rate, less exposure time is required and polymer degradation is reduced. Because electrons carry a charge, electron beams are less penetrating than both gamma and X-rays.

Electrostatic particle accelerators

A 1960s single stage 2 MeV linear Van de Graaff accelerator, here opened for maintenance

Historically, the first accelerators used simple technology of a

single static high voltage to accelerate charged particles. The charged

particle was accelerated through an evacuated tube with an electrode at

either end, with the static potential across it. Since the particle

passed only once through the potential difference, the output energy was

limited to the accelerating voltage of the machine. While this method

is still extremely popular today, with the electrostatic accelerators

greatly out-numbering any other type, they are more suited to lower

energy studies owing to the practical voltage limit of about 1 MV for

air insulated machines, or 30 MV when the accelerator is operated in a

tank of pressurized gas with high dielectric strength, such as sulfur hexafluoride. In a tandem accelerator

the potential is used twice to accelerate the particles, by reversing

the charge of the particles while they are inside the terminal. This is

possible with the acceleration of atomic nuclei by using anions (negatively charged ions),

and then passing the beam through a thin foil to strip electrons off

the anions inside the high voltage terminal, converting them to cations

(positively charged ions), which are accelerated again as they leave the

terminal.

The two main types of electrostatic accelerator are the Cockcroft-Walton accelerator, which uses a diode-capacitor voltage multiplier to produce high voltage, and the Van de Graaff accelerator,

which uses a moving fabric belt to carry charge to the high voltage

electrode. Although electrostatic accelerators accelerate particles

along a straight line, the term linear accelerator is more often used

for accelerators that employ oscillating rather than static electric

fields.

Electrodynamic (electromagnetic) particle accelerators

Due

to the high voltage ceiling imposed by electrical discharge, in order

to accelerate particles to higher energies, techniques involving dynamic

fields rather than static fields are used. Electrodynamic acceleration

can arise from either of two mechanisms: non-resonant magnetic induction, or resonant circuits or cavities excited by oscillating RF fields.

Electrodynamic accelerators can be linear, with particles accelerating in a straight line, or circular, using magnetic fields to bend particles in a roughly circular orbit.

Magnetic induction accelerators

Magnetic

induction accelerators accelerate particles by induction from an

increasing magnetic field, as if the particles were the secondary

winding in a transformer. The increasing magnetic field creates a

circulating electric field which can be configured to accelerate the

particles. Induction accelerators can be either linear or circular.

Linear induction accelerators

Linear induction accelerators utilize ferrite-loaded, non-resonant

induction cavities. Each cavity can be thought of as two large

washer-shaped disks connected by an outer cylindrical tube. Between the

disks is a ferrite toroid. A voltage pulse applied between the two

disks causes an increasing magnetic field which inductively couples

power into the charged particle beam.

The linear induction accelerator was invented by Christofilos in the 1960s.

Linear induction accelerators are capable of accelerating very high

beam currents (>1000 A) in a single short pulse. They have been used

to generate X-rays for flash radiography (e.g. DARHT at LANL), and have been considered as particle injectors for magnetic confinement fusion and as drivers for free electron lasers.

Betatrons

The Betatron is a circular magnetic induction accelerator, invented by Donald Kerst in 1940 for accelerating electrons. The concept originates ultimately from Norwegian-German scientist Rolf Widerøe.

These machines, like synchrotrons, use a donut-shaped ring magnet (see

below) with a cyclically increasing B field, but accelerate the

particles by induction from the increasing magnetic field, as if they

were the secondary winding in a transformer, due to the changing

magnetic flux through the orbit.

Achieving constant orbital radius while supplying the proper

accelerating electric field requires that the magnetic flux linking the

orbit be somewhat independent of the magnetic field on the orbit,

bending the particles into a constant radius curve. These machines have

in practice been limited by the large radiative losses suffered by the

electrons moving at nearly the speed of light in a relatively small

radius orbit.

Linear accelerators

In a linear particle accelerator

(linac), particles are accelerated in a straight line with a target of

interest at one end. They are often used to provide an initial

low-energy kick to particles before they are injected into circular

accelerators. The longest linac in the world is the Stanford Linear Accelerator, SLAC, which is 3 km (1.9 mi) long. SLAC is an electron-positron collider.

Linear high-energy accelerators use a linear array of plates (or

drift tubes) to which an alternating high-energy field is applied. As

the particles approach a plate they are accelerated towards it by an

opposite polarity charge applied to the plate. As they pass through a

hole in the plate, the polarity

is switched so that the plate now repels them and they are now

accelerated by it towards the next plate. Normally a stream of "bunches"

of particles are accelerated, so a carefully controlled AC voltage is

applied to each plate to continuously repeat this process for each

bunch.

As the particles approach the speed of light the switching rate of the electric fields becomes so high that they operate at radio frequencies, and so microwave cavities are used in higher energy machines instead of simple plates.

Linear accelerators are also widely used in medicine, for radiotherapy and radiosurgery. Medical grade linacs accelerate electrons using a klystron and a complex bending magnet arrangement which produces a beam of 6-30 MeV energy. The electrons can be used directly or they can be collided with a target to produce a beam of X-rays. The reliability, flexibility and accuracy of the radiation beam produced has largely supplanted the older use of cobalt-60 therapy as a treatment tool.

Circular or cyclic RF accelerators

In

the circular accelerator, particles move in a circle until they reach

sufficient energy. The particle track is typically bent into a circle

using electromagnets. The advantage of circular accelerators over linear accelerators (linacs)

is that the ring topology allows continuous acceleration, as the

particle can transit indefinitely. Another advantage is that a circular

accelerator is smaller than a linear accelerator of comparable power

(i.e. a linac would have to be extremely long to have the equivalent

power of a circular accelerator).

Depending on the energy and the particle being accelerated,

circular accelerators suffer a disadvantage in that the particles emit synchrotron radiation. When any charged particle is accelerated, it emits electromagnetic radiation and secondary emissions.

As a particle traveling in a circle is always accelerating towards the

center of the circle, it continuously radiates towards the tangent of

the circle. This radiation is called synchrotron light

and depends highly on the mass of the accelerating particle. For this

reason, many high energy electron accelerators are linacs. Certain

accelerators (synchrotrons) are however built specially for producing synchrotron light (X-rays).

Since the special theory of relativity requires that matter always travels slower than the speed of light in a vacuum,

in high-energy accelerators, as the energy increases the particle speed

approaches the speed of light as a limit, but never attains it.

Therefore, particle physicists do not generally think in terms of speed,

but rather in terms of a particle's energy or momentum, usually measured in electron volts (eV). An important principle for circular accelerators, and particle beams in general, is that the curvature

of the particle trajectory is proportional to the particle charge and

to the magnetic field, but inversely proportional to the (typically relativistic) momentum.

Cyclotrons

The earliest operational circular accelerators were cyclotrons, invented in 1929 by Ernest Lawrence at the University of California, Berkeley. Cyclotrons have a single pair of hollow "D"-shaped plates to accelerate the particles and a single large dipole magnet

to bend their path into a circular orbit. It is a characteristic

property of charged particles in a uniform and constant magnetic field B

that they orbit with a constant period, at a frequency called the cyclotron frequency, so long as their speed is small compared to the speed of light c.

This means that the accelerating D's of a cyclotron can be driven at a

constant frequency by a radio frequency (RF) accelerating power source,

as the beam spirals outwards continuously. The particles are injected in

the center of the magnet and are extracted at the outer edge at their

maximum energy.

Cyclotrons reach an energy limit because of relativistic effects

whereby the particles effectively become more massive, so that their

cyclotron frequency drops out of sync with the accelerating RF.

Therefore, simple cyclotrons can accelerate protons only to an energy of

around 15 million electron volts (15 MeV, corresponding to a speed of

roughly 10% of c), because the protons get out of phase with the

driving electric field. If accelerated further, the beam would continue

to spiral outward to a larger radius but the particles would no longer

gain enough speed to complete the larger circle in step with the

accelerating RF. To accommodate relativistic effects the magnetic field

needs to be increased to higher radii as is done in isochronous cyclotrons. An example of an isochronous cyclotron is the PSI Ring cyclotron

in Switzerland, which provides protons at the energy of 590 MeV which

corresponds to roughly 80% of the speed of light. The advantage of such a

cyclotron is the maximum achievable extracted proton current which is

currently 2.2 mA. The energy and current correspond to 1.3 MW beam power

which is the highest of any accelerator currently existing.

Synchrocyclotrons and isochronous cyclotrons

A classic cyclotron can be modified to increase its energy limit. The historically first approach was the synchrocyclotron, which accelerates the particles in bunches. It uses a constant magnetic field  ,

but reduces the accelerating field's frequency so as to keep the

particles in step as they spiral outward, matching their mass-dependent cyclotron resonance

frequency. This approach suffers from low average beam intensity due to

the bunching, and again from the need for a huge magnet of large radius

and constant field over the larger orbit demanded by high energy.

,

but reduces the accelerating field's frequency so as to keep the

particles in step as they spiral outward, matching their mass-dependent cyclotron resonance

frequency. This approach suffers from low average beam intensity due to

the bunching, and again from the need for a huge magnet of large radius

and constant field over the larger orbit demanded by high energy.

The second approach to the problem of accelerating relativistic particles is the isochronous cyclotron.

In such a structure, the accelerating field's frequency (and the

cyclotron resonance frequency) is kept constant for all energies by

shaping the magnet poles so to increase magnetic field with radius.

Thus, all particles get accelerated in isochronous

time intervals. Higher energy particles travel a shorter distance in

each orbit than they would in a classical cyclotron, thus remaining in

phase with the accelerating field. The advantage of the isochronous

cyclotron is that it can deliver continuous beams of higher average

intensity, which is useful for some applications. The main disadvantages

are the size and cost of the large magnet needed, and the difficulty in

achieving the high magnetic field values required at the outer edge of

the structure.

Synchrocyclotrons have not been built since the isochronous cyclotron was developed.

Synchrotrons

Aerial photo of the

Tevatron at

Fermilab,

which resembles a figure eight. The main accelerator is the ring above;

the one below (about half the diameter, despite appearances) is for

preliminary acceleration, beam cooling and storage, etc.

To reach still higher energies, with relativistic mass approaching or

exceeding the rest mass of the particles (for protons, billions of

electron volts or GeV), it is necessary to use a synchrotron.

This is an accelerator in which the particles are accelerated in a ring

of constant radius. An immediate advantage over cyclotrons is that the

magnetic field need only be present over the actual region of the

particle orbits, which is much narrower than that of the ring. (The

largest cyclotron built in the US had a 184-inch-diameter (4.7 m) magnet

pole, whereas the diameter of synchrotrons such as the LEP and LHC

is nearly 10 km. The aperture of the two beams of the LHC is of the

order of a centimeter.) The LHC contains 16 RF cavities, 1232

superconducting dipole magnets for beam steering, and 24 quadrupoles for

beam focusing.

Even at this size, the LHC is limited by its ability to steer the

particles without them going adrift. This limit is theorized to occur at

14TeV.

However, since the particle momentum increases during

acceleration, it is necessary to turn up the magnetic field B in

proportion to maintain constant curvature of the orbit. In consequence,

synchrotrons cannot accelerate particles continuously, as cyclotrons

can, but must operate cyclically, supplying particles in bunches, which

are delivered to a target or an external beam in beam "spills" typically

every few seconds.

Since high energy synchrotrons do most of their work on particles that are already traveling at nearly the speed of light c, the time to complete one orbit of the ring is nearly constant, as is the frequency of the RF cavity resonators used to drive the acceleration.

In modern synchrotrons, the beam aperture is small and the

magnetic field does not cover the entire area of the particle orbit as

it does for a cyclotron, so several necessary functions can be

separated. Instead of one huge magnet, one has a line of hundreds of

bending magnets, enclosing (or enclosed by) vacuum connecting pipes. The

design of synchrotrons was revolutionized in the early 1950s with the

discovery of the strong focusing concept. The focusing of the beam is handled independently by specialized quadrupole magnets, while the acceleration itself is accomplished in separate RF sections, rather similar to short linear accelerators.

Also, there is no necessity that cyclic machines be circular, but

rather the beam pipe may have straight sections between magnets where

beams may collide, be cooled, etc. This has developed into an entire

separate subject, called "beam physics" or "beam optics".

More complex modern synchrotrons such as the Tevatron, LEP, and LHC may deliver the particle bunches into storage rings

of magnets with a constant magnetic field, where they can continue to

orbit for long periods for experimentation or further acceleration. The

highest-energy machines such as the Tevatron and LHC are actually

accelerator complexes, with a cascade of specialized elements in series,

including linear accelerators for initial beam creation, one or more

low energy synchrotrons to reach intermediate energy, storage rings

where beams can be accumulated or "cooled" (reducing the magnet aperture

required and permitting tighter focusing; see beam cooling), and a last large ring for final acceleration and experimentation.

Segment of an electron synchrotron at

DESYElectron synchrotrons

Circular electron accelerators fell somewhat out of favor for particle physics around the time that SLAC's

linear particle accelerator was constructed, because their synchrotron

losses were considered economically prohibitive and because their beam

intensity was lower than for the unpulsed linear machines. The Cornell Electron Synchrotron,

built at low cost in the late 1970s, was the first in a series of

high-energy circular electron accelerators built for fundamental

particle physics, the last being LEP, built at CERN, which was used from 1989 until 2000.

A large number of electron synchrotrons have been built in the past two decades, as part of synchrotron light sources that emit ultraviolet light and X rays; see below.

Storage rings

For some applications, it is useful to store beams of high energy particles for some time (with modern high vacuum technology, up to many hours) without further acceleration. This is especially true for colliding beam accelerators, in which two beams moving in opposite directions are made to collide with each other, with a large gain in effective collision energy.

Because relatively few collisions occur at each pass through the

intersection point of the two beams, it is customary to first accelerate

the beams to the desired energy, and then store them in storage rings,

which are essentially synchrotron rings of magnets, with no significant

RF power for acceleration.

Synchrotron radiation sources

Some circular accelerators have been built to deliberately generate radiation (called synchrotron light) as X-rays also called synchrotron radiation, for example the Diamond Light Source which has been built at the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in England or the Advanced Photon Source at Argonne National Laboratory in Illinois, USA. High-energy X-rays are useful for X-ray spectroscopy of proteins or X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS), for example.

Synchrotron radiation is more powerfully emitted by lighter particles, so these accelerators are invariably electron accelerators. Synchrotron radiation allows for better imaging as researched and developed at SLAC's SPEAR.

Fixed-Field Alternating Gradient Accelerators

Fixed-Field Alternating Gradient accelerators (FFA)s, in which a magnetic field which is fixed in time, but with a radial variation to achieve strong focusing,

allows the beam to be accelerated with a high repetition rate but in a

much smaller radial spread than in the cyclotron case. Isochronous FFAs,

like isochronous cyclotrons, achieve continuous beam operation, but

without the need for a huge dipole bending magnet covering the entire

radius of the orbits. Some new developments in FFAs are covered in.

History

Ernest Lawrence's first cyclotron was a mere 4 inches (100 mm) in

diameter. Later, in 1939, he built a machine with a 60-inch diameter

pole face, and planned one with a 184-inch diameter in 1942, which was, however, taken over for World War II-related work connected with uranium isotope separation; after the war it continued in service for research and medicine over many years.

The first large proton synchrotron was the Cosmotron at Brookhaven National Laboratory, which accelerated protons to about 3 GeV (1953–1968). The Bevatron at Berkeley, completed in 1954, was specifically designed to accelerate protons to sufficient energy to create antiprotons, and verify the particle-antiparticle symmetry of nature, then only theorized. The Alternating Gradient Synchrotron (AGS) at Brookhaven (1960–) was the first large synchrotron with alternating gradient, "strong focusing"

magnets, which greatly reduced the required aperture of the beam, and

correspondingly the size and cost of the bending magnets. The Proton Synchrotron, built at CERN (1959–), was the first major European particle accelerator and generally similar to the AGS.

The Stanford Linear Accelerator,

SLAC, became operational in 1966, accelerating electrons to 30 GeV in a

3 km long waveguide, buried in a tunnel and powered by hundreds of

large klystrons.

It is still the largest linear accelerator in existence, and has been

upgraded with the addition of storage rings and an electron-positron

collider facility. It is also an X-ray and UV synchrotron photon source.

The Fermilab Tevatron

has a ring with a beam path of 4 miles (6.4 km). It has received

several upgrades, and has functioned as a proton-antiproton collider

until it was shut down due to budget cuts on September 30, 2011. The

largest circular accelerator ever built was the LEP synchrotron at CERN with a circumference 26.6 kilometers, which was an electron/positron collider. It achieved an energy of 209 GeV before it was dismantled in 2000 so that the tunnel could be used for the Large Hadron Collider

(LHC). The LHC is a proton collider, and currently the world's largest

and highest-energy accelerator, achieving 6.5 TeV energy per beam (13

TeV in total).

The aborted Superconducting Super Collider (SSC) in Texas

would have had a circumference of 87 km. Construction was started in

1991, but abandoned in 1993. Very large circular accelerators are

invariably built in tunnels a few metres wide to minimize the disruption

and cost of building such a structure on the surface, and to provide

shielding against intense secondary radiations that occur, which are

extremely penetrating at high energies.

Current accelerators such as the Spallation Neutron Source, incorporate superconducting cryomodules. The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider, and Large Hadron Collider also make use of superconducting magnets and RF cavity resonators to accelerate particles.

Targets

The

output of a particle accelerator can generally be directed towards

multiple lines of experiments, one at a given time, by means of a

deviating electromagnet.

This makes it possible to operate multiple experiments without needing

to move things around or shutting down the entire accelerator beam.

Except for synchrotron radiation sources, the purpose of an accelerator

is to generate high-energy particles for interaction with matter.

This is usually a fixed target, such as the phosphor coating on the back of the screen in the case of a television tube; a piece of uranium

in an accelerator designed as a neutron source; or a tungsten target

for an X-ray generator. In a linac, the target is simply fitted to the

end of the accelerator. The particle track in a cyclotron is a spiral

outwards from the centre of the circular machine, so the accelerated

particles emerge from a fixed point as for a linear accelerator.

For synchrotrons, the situation is more complex. Particles are

accelerated to the desired energy. Then, a fast acting dipole magnet is

used to switch the particles out of the circular synchrotron tube and

towards the target.

A variation commonly used for particle physics research is a collider, also called a storage ring collider.

Two circular synchrotrons are built in close proximity – usually on top

of each other and using the same magnets (which are then of more

complicated design to accommodate both beam tubes). Bunches of particles

travel in opposite directions around the two accelerators and collide

at intersections between them. This can increase the energy enormously;

whereas in a fixed-target experiment the energy available to produce new

particles is proportional to the square root of the beam energy, in a

collider the available energy is linear.

Higher energies

A

Livingston

chart depicting progress in collision energy through 2010. The LHC is

the largest collision energy to date, but also represents the first

break in the

log-linear trend.

At present the highest energy accelerators are all circular

colliders, but both hadron accelerators and electron accelerators are

running into limits. Higher energy hadron and ion cyclic accelerators

will require accelerator tunnels of larger physical size due to the

increased beam rigidity.

For cyclic electron accelerators, a limit on practical bend

radius is placed by synchrotron radiation losses and the next generation

will probably be linear accelerators 10 times the current length. An

example of such a next generation electron accelerator is the proposed

40 km long International Linear Collider.

It is believed that plasma wakefield acceleration

in the form of electron-beam "afterburners" and standalone laser

pulsers might be able to provide dramatic increases in efficiency over

RF accelerators within two to three decades. In plasma wakefield

accelerators, the beam cavity is filled with a plasma (rather than

vacuum). A short pulse of electrons or laser light either constitutes or

immediately precedes the particles that are being accelerated. The

pulse disrupts the plasma, causing the charged particles in the plasma

to integrate into and move toward the rear of the bunch of particles

that are being accelerated. This process transfers energy to the

particle bunch, accelerating it further, and continues as long as the

pulse is coherent.

Energy gradients as steep as 200 GeV/m have been achieved over millimeter-scale distances using laser pulsers

and gradients approaching 1 GeV/m are being produced on the

multi-centimeter-scale with electron-beam systems, in contrast to a

limit of about 0.1 GeV/m for radio-frequency acceleration alone.

Existing electron accelerators such as SLAC

could use electron-beam afterburners to greatly increase the energy of

their particle beams, at the cost of beam intensity. Electron systems in

general can provide tightly collimated, reliable beams; laser systems

may offer more power and compactness. Thus, plasma wakefield

accelerators could be used – if technical issues can be resolved – to

both increase the maximum energy of the largest accelerators and to

bring high energies into university laboratories and medical centres.

Higher than 0.25 GeV/m gradients have been achieved by a dielectric laser accelerator, which may present another viable approach to building compact high-energy accelerators.

Using femtosecond duration laser pulses, an electron accelerating

gradient 0.69 Gev/m was recorded for dielectric laser accelerators. Higher gradients of the order of 1 to 6 GeV/m are anticipated after further optimizations.

Black hole production and public safety concerns

In the future, the possibility of a black hole production at the

highest energy accelerators may arise if certain predictions of superstring theory are accurate. This and other possibilities have led to public safety concerns that have been widely reported in connection with the LHC,

which began operation in 2008. The various possible dangerous scenarios

have been assessed as presenting "no conceivable danger" in the latest

risk assessment produced by the LHC Safety Assessment Group. If black holes are produced, it is theoretically predicted that such small black holes should evaporate extremely quickly via Bekenstein-Hawking radiation, but which is as yet experimentally unconfirmed. If colliders can produce black holes, cosmic rays (and particularly ultra-high-energy cosmic rays, UHECRs) must have been producing them for eons, but they have yet to harm anybody.

It has been argued that to conserve energy and momentum, any black

holes created in a collision between an UHECR and local matter would

necessarily be produced moving at relativistic speed with respect to the

Earth, and should escape into space, as their accretion and growth rate

should be very slow, while black holes produced in colliders (with

components of equal mass) would have some chance of having a velocity

less than Earth escape velocity, 11.2 km per sec, and would be liable to

capture and subsequent growth. Yet even on such scenarios the

collisions of UHECRs with white dwarfs and neutron stars would lead to

their rapid destruction, but these bodies are observed to be common

astronomical objects. Thus if stable micro black holes should be

produced, they must grow far too slowly to cause any noticeable

macroscopic effects within the natural lifetime of the solar system.

Accelerator operator

The

use of non-standard technologies such as superconductivity, cryogenics

and radiofrequency pose challenges for the safe operation of accelerator

facilities. An

accelerator operator

controls the operation of a particle accelerator used in research

experiments, reviews an experiment schedule to determine experiment

parameters specified by an experimenter (

physicist), adjust particle beam parameters such as

aspect ratio,

current intensity, and position on target, communicates with and

assists accelerator maintenance personnel to ensure readiness of support

systems, such as

vacuum,

magnet power supplies and controls,

low conductivity water (LCW) cooling, and

radiofrequency power supplies and controls. Additionally, the accelerator operator maintains a record of accelerator related events.