Effects of climate change on oceans provides information on the various effects that climate change has on oceans. Climate change can affect sea levels, coastlines, ocean acidification, ocean currents, seawater, sea surface temperatures, tides, the sea floor, weather, and trigger several changes in ocean bio-geochemistry; all of these affect the functioning of a society.

Sea level

Coasts

There are a number of factors affecting rising sea levels, including the thermal expansion of seawater, the melting of glaciers and ice sheets on land, and possibly human changes to groundwater storage.

The consensus of many studies of coastal tide gauge records is that during the past century sea level has risen worldwide at an average rate of 1–2 mm/yr reflecting a net flux of heat into the surface of the land and oceans. Corresponding studies based on satellite altimetry shows that this rate has increased to closer to 3 mm/yr during the more completely monitored past 20 years. A recent review of the literature suggests that 30% of the sea level rise since 1993 is due to thermal expansion and 55% due to continental ice melt, both resulting from warming global temperatures. In another study, results estimate the heat content of the ocean in the upper 700 meters has increased significantly from 1955–2010. It has to be reminded that in this context the usage of the word heat is extremely improper, as heat cannot be stored in a body but only exchanged between bodies. Observations of the changes in "heat content" of the ocean are important for providing realistic estimates of how the ocean is changing with global warming. An even more recent study of the contributions to global sea level due to melting of the two large ice sheets based on satellite measurements of gravity fluctuations suggests that the melting of these alone are causing global sea level to about 1 mm/yr. In a recent modeling study, scientists used an earth system model to study several variables of the ocean, one of which was the "heat content" of the oceans over the past several hundred years. The earth system model incorporated the atmosphere, land surface processes, and other earth components to make it more realistic and similar to observations. Results of their model simulation showed that since 1500, the ocean "heat content" of the upper 500 m has increased.

The connection between sea level rise and ocean thermal expansion follows from Charles's law (also known as the law of volumes) put simply states that the volume of a given mass is proportional to its temperature. This contribution to sea level is monitored by oceanographers using a succession of temperature measuring profiling instruments, which is then compiled at national data centers such as the United States National Oceanographic Data Center. The International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Fifth Assessment Report estimates that the upper ocean (surface to 750 m deep) has warmed by 0.09 to 0.13 degrees C per decade over the past 40 years. Other processes important in influencing global sea level include changes to groundwater storage including dams and reservoirs.

Global warming also has an enormous impact with respect to melting glaciers and ice sheets. Higher global temperatures melt glaciers such as the one in Greenland, which flow into the oceans, adding to the amount of seawater. A large rise (on the order of several feet) in global sea levels poses many threats. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “such a rise would inundate coastal wetlands and lowlands, erode beaches, increase the risk of flooding, and increase the salinity of estuaries, aquifers, and wetlands.” The seasonal cycles are closely linked with the seasonal changes in sea ice and sea surface temperatures. The timing and amplitude of the seasonal cycle has been altered by global warming.

Superimposed on the global rise in sea level, is strong regional and decadal variability which may cause sea level along a particular coastline to decline with time (for example along the Canadian eastern seaboard), or to rise faster than the global average. Regions that have shown a rapid rise in sea level during the past two decades include the western tropical Pacific and the United States northeastern seaboard. These regional variations in sea level are the result of many factors, such as local sedimentation rates, geomorphology, post-glacial rebound, and coastal erosion. Large storm events, such as Hurricane Sandy in the eastern Atlantic, can dramatically alter coastlines and affect sea level rise as well.

Coastal regions would be most affected by rising sea levels. The increase in sea level along the coasts of continents, especially North America are much more significant than the global average. According to 2007 estimates by the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), “global average sea level will rise between 0.6 and 2 feet (0.18 to 0.59 meters) in the next century. Along the U.S. Mid-Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, however, sea level rose in the last century 5 to 6 inches more than the global average. This is due to the subsiding of coastal lands. The sea level along the U.S. Pacific coast has also increased more than the global average but less than along the Atlantic coast. This can be explained by the varying continental margins along both coasts; the Atlantic type continental margin is characterized by a wide, gently sloping continental shelf, while the Pacific type continental margin incorporates a narrow shelf and slope descending into a deep trench. Since low-sloping coastal regions should retreat faster than higher-sloping regions, the Atlantic coast is more vulnerable to sea level rise than the Pacific coast.

Society

The rise in sea level along coastal regions carries implications for a wide range of habitats and inhabitants. Firstly, rising sea levels will have a serious impact on beaches— a place which humans love to visit recreationally and a prime location for real estate. It is ideal to live on the coast, due to a more moderate climate and pleasant scenery, but beachfront property is at risk from eroding land and rising sea levels. Since the threat posed by rising sea levels has become more prominent, property owners and local government have taken measures to prepare for the worst. For example, “Maine has enacted a policy declaring that shorefront buildings will have to be moved to enable beaches and wetlands to migrate inland to higher ground.” Additionally, many coastal states add sand to their beaches to offset shore erosion, and many property owners have elevated their structures in low-lying areas. As a result of the erosion and ruin of properties by large storms on coastal lands, governments have looked into buying land and having residents relocate further inland. The seas now absorb much of human-generated carbon dioxide, which then affects temperature change. The oceans store 93 percent of that energy which helps keep the planet livable by moderating temperatures.

Another important coastal habitat that is threatened by sea level rise is wetlands, which “occur along the margins of estuaries and other shore areas that are protected from the open ocean and include swamps, tidal flats, coastal marshes and bayous.” Wetlands are extremely vulnerable to rising sea levels, since they are within several feet of sea level. The threat posed to wetlands is serious, due to the fact that they are highly productive ecosystems, and they have an enormous impact on the economy of surrounding areas. Wetlands in the U.S. are rapidly disappearing due to an increase in housing, industry, and agriculture, and rising sea levels contribute to this dangerous trend. As a result of rising sea levels, the outer boundaries of wetlands tend to erode, forming new wetlands more inland. According to the EPA, “the amount of newly created wetlands, however, could be much smaller than the lost area of wetlands— especially in developed areas protected with bulkheads, dikes, and other structures that keep new wetlands from forming inland.” When estimating a sea level rise within the next century of 50 cm (20 inches), the U.S. would lose 38% to 61% of its existing coastal wetlands.

A rise in sea level will have a negative impact not only on coastal property and economy but on our supply of fresh water. According to the EPA, “Rising sea level increases the salinity of both surface water and ground water through salt water intrusion.” Coastal estuaries and aquifers, therefore, are at a high risk of becoming too saline from rising sea levels. With respect to estuaries, an increase in salinity would threaten aquatic animals and plants that cannot tolerate high levels of salinity. Aquifers often serve as a primary water supply to surrounding areas, such as Florida's Biscayne aquifer, which receives freshwater from the Everglades and then supplies water to the Florida Keys. Rising sea levels would submerge low-lying areas of the Everglades, and salinity would greatly increase in portions of the aquifer. The considerable rise in sea level and the decreasing amounts of freshwater along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts would make those areas rather uninhabitable. Many economists predict that global warming will be one of the main economic threats to the West Coast, specifically in California. "Low-lying coastal areas, such as along the Gulf Coast, are particularly vulnerable to sea-level rise and stronger storms—and those risks are reflected in rising insurance rates and premiums. In Florida, for example, the average price of a homeowners’ policy increased by 77 percent between 2001 and 2006."

Global issue

Since rising sea levels present a pressing problem not only to coastal communities but to the whole global population as well, much scientific research has been performed to analyze the causes and consequences of a rise in sea level. The U.S. Geological Survey has conducted such research, addressing coastal vulnerability to sea level rise and incorporating six physical variables to analyze the changes in sea level: geomorphology; coastal slope (percent); rate of relative sea level rise (mm/yr); shoreline erosion and acceleration rates (m/yr); mean tidal range (m); and mean wave height (m). The research was conducted on the various coasts of the U.S., and the results are very useful for future reference. Along the Pacific coast, the most vulnerable areas are low-lying beaches, and “their susceptibility is primarily a function of geomorphology and coastal slope.” With regard to research performed along the Atlantic coast, the most vulnerable areas to sea level rise were found to be along the Mid-Atlantic coast (Maryland to North Carolina) and Northern Florida, since these are “typically high-energy coastlines where the regional coastal slope is low and where the major landform type is a barrier island.” For the Gulf coast, the most vulnerable areas are along the Louisiana-Texas coast. According to the results, “the highest-vulnerability areas are typically lower-lying beach and marsh areas; their susceptibility is primarily a function of geomorphology, coastal slope and rate of relative sea-level rise.”

Many humanitarians and environmentalists believe that political policy needs to have a bigger role in carbon dioxide reduction. Humans have a substantial influence on the rise of sea level because we emit increasing levels of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere through automobile use and industry. A higher amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere leads to higher global temperatures, which then results in thermal expansion of seawater and melting of glaciers and ice sheets.

Ocean currents

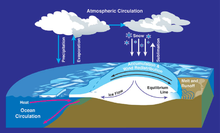

The currents in the world's oceans are a result of varying temperatures associated with the changing latitudes of our planet. As the atmosphere is warmed nearest the equator, the hot air at the surface of our planet is heated, causing it to rise and draw in cooler air to take its place, creating what is known as circulation cells. This ultimately causes the air to be significantly colder near the poles than at the equator.

Wind patterns associated with these circulation cells drive surface currents which push the surface water to the higher latitudes where the air is colder. This cools the water down enough to where it is capable of dissolving more gasses and minerals, causing it to become very dense in relation to lower latitude waters, which in turn causes it to sink to the bottom of the ocean, forming what is known as North Atlantic Deep Water (NADW) in the north and Antarctic Bottom Water (AABW) in the south. Driven by this sinking and the upwelling that occurs in lower latitudes, as well as the driving force of the winds on surface water, the ocean currents act to circulate water throughout the entire sea. When global warming is added into the equation, changes occur, especially in the regions where deep water is formed. With the warming of the oceans and subsequent melting of glaciers and the polar ice caps, more and more fresh water is released into the high latitude regions where deep water is formed. This extra water that gets thrown into the chemical mix dilutes the contents of the water arriving from lower latitudes, reducing the density of the surface water. Consequently, the water sinks more slowly than it normally would.

It is important to note that ocean currents provide the necessary nutrients for life to sustain itself in the lower latitudes. Should the currents slow down, fewer nutrients would be brought to sustain ocean life resulting in a crumbling of the food chain and irreparable damage to the marine ecosystem. Slower currents would also mean less carbon fixation. Naturally, the ocean is the largest sink within which carbon is stored. When waters become saturated with carbon, excess carbon has nowhere to go, because the currents are not bringing up enough fresh water to fix the excess. This causes a rise in atmospheric carbon which in turn causes positive feedback that can lead to a runaway greenhouse effect.

Ocean acidification

The oceans cover approximately 71 percent of the Earth's surface and support a diverse range of ecosystems, which are home to over 50 percent of all the species on the planet. Oceans regulate climate and weather as well as providing nutrition for a vast variety of species, humans included. Covering such an extensive part of the planet has allowed the oceans to absorb a large portion of the carbon dioxide (CO

2) from the atmosphere. This process is part of the carbon cycle in which the fluxes of carbon dioxide (CO

2) in Earth's atmosphere, biosphere and lithosphere are described. Humans have drastically added to the amount of carbon dioxide (CO

2) in the atmosphere through the burning of fossil fuels and the process of deforestation. Oceans work as a sink absorbing excess anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO

2). As the oceans absorb anthropogenic carbon dioxide (CO

2) it breaks down into carbonic acid, a mild acid, this neutralizes the normally alkaline ocean water. As a result, the pH in the oceans is declining (ocean acidification).

In the research surrounding global climate change we are only just

beginning to realize that our oceans can sequester a finite amount of CO

2

before we start seeing impacts on marine life that could lead to

devastating losses. Acidification of our oceans has the potential to

drastically alter life as we know it - from extreme weather patterns and food scarcity to a loss of millions of species from the planet.

The rate at which ocean acidification will occur may be influenced by the rate of surface ocean warming, because the chemical equilibria that govern seawater pH are temperature-dependent. Greater seawater warming could lead to a smaller change in pH for a given increase in CO2.

Another effect of global warming on the carbon cycle is ocean acidification. The ocean and the atmosphere constantly act to maintain a state of equilibrium, so a rise in atmospheric carbon naturally leads to a rise in oceanic carbon. When carbon dioxide is dissolved in water it forms hydrogen and bicarbonate ions, which in turn breaks down to hydrogen and carbonate ions. All these extra hydrogen ions increase the acidity of the ocean and make survival harder for planktonic organisms that depend on calcium carbonate to form their shells. A decrease in the base of the food chain will, once again, be destructive to the ecosystems to which they belong. With fewer of these photosynthetic organisms present at the surface of the ocean, less carbon dioxide will be converted to oxygen, thereby allowing the greenhouse gasses to go unchecked.

Steps are being taken to combat the potentially devastating effects of ocean acidification, and scientists worldwide are coming together to solve the problem that is known as “global warming’s evil twin”.

Between 1750 and 2000, surface-ocean pH has decreased by about 0.1, from about 8.2 to about 8.1. Surface-ocean pH has probably not been below 8.1 during the past 2 million years. Projections suggest that surface-ocean pH could decrease by an additional 0.3–0.4 units by 2100. Ocean acidification could threaten coral reefs, fisheries, protected species, and other natural resources of value to society.

Effects of acidification

The effects of ocean acidification can already be seen and have been happening since the start of the industrial revolution, with pH levels of the ocean dropping by 0.1 since the pre-industrial revolution times. An effect called coral bleaching can be seen on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, where ocean acidification's effects are already taking place. Coral bleaching is when unicellular organisms that help make up the coral begin to die off and leave the coral giving it a white appearance. These unicellular organisms are important for the coral to feed and get the proper nutrition that is necessary to survive, leaving the coral weak and malnourished. This results in weaker coral that can die more easily and offer less protection to the organisms that depend on coral for shelter and protection. Increased acidity can also dissolve an organism's shell, threatening entire groups of shellfish and zooplankton and in turn, presenting a threat to the food chain and ecosystem.

Without strong shells, surviving and growing becomes more of a challenge for marine life that depend on calcified shells. The populations of these animals becomes smaller and individual members of the species turn weaker. The fish that rely on these smaller shell constructing animals for food now have a decreased supply, and animals that need coral reefs for shelter now have less protection. The effects of ocean acidification decrease population sizes of marine life and may cause an economic disruption if enough fish die off, which can seriously harm the global economy as the fishing industry makes a lot of money worldwide.

Ocean acidification can also have affects on marine fish larvae. It internally affects their olfactory systems, which is a crucial part of their development, especially in the beginning stage of their life. Orange clownfish larvae mostly live on oceanic reefs that are surrounded by vegetative islands. With the use of their sense of smell, larvae are known to be able to detect the differences between reefs surrounded by vegetative islands and reefs not surrounded by vegetative islands. Clownfish larvae need to be able to distinguish between these two destinations to have the ability to locate an area that is satisfactory for their growth. Another use for marine fish olfactory systems is to help in determining the difference between their parents and other adult fish in order to avoid inbreeding.

At James Cook University's experimental aquarium facility, clownfish were sustained in non-manipulated seawater that obtained a pH of 8.15 ± 0.07 which is similar to our current ocean's pH. To test for effects of different pH levels, seawater was manipulated to three different pH levels, including the non-manipulated pH. The two opposing pH levels correspond with climate change models that predict future atmospheric CO2 levels. In the year 2100 the model predicts that we could potentially acquire CO2 levels at 1,000 ppm, which correlates with the pH of 7.8 ± 0.05. Continuing even further into the next century, we could have CO2 levels at 1,700 ppm, which correlates with a pH of 7.6 ± 0.05.

Results of this experiment show that when larvae is exposed to a pH of 7.8 ± 0.05 their reaction to environmental cues differs drastically to larvae's reaction to cues in a non-manipulated pH. Not only did if effect their reaction to environmental cues but their reaction to parental cues was also skewed compared to the larvae reared in a non-manipulated pH of 8.15 ± 0.07. At the pH of 7.6 ± 0.05 larvae had no reaction to any type of cue. These results display the negative outcomes that could possibly be the future for marine fish larvae.

Oxygen depletion

Ocean deoxygenation is projected to increase hypoxia by 10%, and triple suboxic waters (oxygen concentrations 98% less than the mean surface concentrations), for each 1 °C of upper ocean warming.

Marine life

Research indicates that increasing ocean temperatures are taking a toll on the marine ecosystem. A study on phytoplankton changes in the Indian Ocean indicates a decline of up to 20% in marine phytoplankton during the past six decades. During the summer, the western Indian Ocean is home to one of the largest concentrations of marine phytoplankton blooms in the world when compared to other oceans in the tropics. Increased warming in the Indian Ocean enhances ocean stratification, which prevents nutrient mixing in the euphotic zone where there is ample light available for photosynthesis. Thus, primary production is constrained and the region's entire food web is disrupted. If rapid warming continues, experts predict that the Indian Ocean will transform into an ecological desert and will no longer be productive. The same study also addresses the abrupt decline of tuna catch rates in the Indian Ocean during the past half century. This decrease is mostly due to increased industrial fisheries, with ocean warming adding further stress to the fish species. These rates show a 50-90% decrease over 5 decades.

A study that describes climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean productivity looked at global-ocean net primary production (NPP) changes detected from satellite measurements of ocean color from 1997 to 2006. These measurements can be used to quantify ocean productivity on a global scale and relate changes to environmental factors. They found an initial increase in NPP from 1997 to 1999 followed by a continuous decrease in productivity after 1999. These trends are propelled by the expansive stratified low-latitude oceans and are closely linked to climate variability. This relationship between the physical environment and ocean biology effects the availability of nutrients for phytoplankton growth since these factors influence variations in upper-ocean temperature and stratification. The downward trends of ocean productivity after 1999 observed in this study can give insight into how climate change can affect marine life in the future.

Effects of Marine Life Danger in Society.

As stated before, marine life has been decreasing in percentage as the time goes on due to the increase in ocean pollution being the main component plastic that is eaten by marine animals. Along with marine life, humans are also being affected by ocean pollution. One of the biggest animal protein industries, as it is the seafood industry, is affected since marine life has been decreasing and it is predicted that if they continue using the harmful techniques that are being used, by 2048 there is the possibility of an ocean without fish. The seafood industry has a big impact in the world’s food industry, proving food for approximately 3 billion people. One of the many famous and trending diets that are out there are the pescatarian diet, in which vegetarian diets followers add fish or other types of seafood in order to obtain the nutrients from the fish. If it comes to the point in which the seafood industry keep growing, as more people are joining this type of food trends and eating more fish (more demand means more production), and using techniques that deteriorate the marine life beyond catching the animals we will end up at the point of no return: where the marine life is extinct and we as humans will not be able to consume such as good source of protein in order to meet the required necessities. The ocean pollution does not mean that only marine life is being damaged, but also that we as humans will deprive ourselves from a great privilege as it is seafood and marine life.

Weather

Global warming also affects weather patterns as they pertain to cyclones. Scientists have found that although there have been fewer cyclones than in the past, the intensity of each cyclone has increased. A simplified definition of what global warming means for the planet is that colder regions would get warmer and warmer regions would get much warmer. However, there is also speculation that the complete opposite could be true. A warmer earth could serve to moderate temperatures worldwide. There is still much that is not understood about the earth's climate, because it is very difficult to make climate models. As such, predicting the effects that global warming might have on our planet is still an inexact science. Global warming is also causing the amount of hazards on the ocean to increase. It has increased the amount of fog at sea level, making it harder for ships to navigate without crashing into other boats or other objects in the ocean. The warmness and dampness of the ground is causing the fog to come closer to the surface level of the ocean. As the rain falls it makes the ground wet, then the warm air rises leaving a layer of cold air that turns into fog causing an unsafe ocean for travel and for working conditions on the ocean. It is also causing the ocean to create more floods due to the fact that it is warming up and the glaciers from the ice age are now melting causing the sea levels to rise, which causes the ocean to take over part of the land and beaches. Glaciers are melting at an alarming rate which is causing the ocean to rise faster than predicted. Inside of this ice there are traces of bubbles that are filled with CO2 that are then released into the atmosphere when they melt causing the greenhouse effect to grow at an even faster rate.

Regional weather patterns across the globe are also changing due to tropical ocean warming. The Indo-Pacific warm pool has been warming rapidly and expanding during the recent decades, largely in response to increased carbon emissions from fossil fuel burning. The warm pool expanded to almost double its size, from an area of 22 million km2 during 1900–1980, to an area of 40 million km2 during 1981–2018. This expansion of the warm pool has altered global rainfall patterns, by changing the life cycle of the Madden Julian Oscillation (MJO), which is the most dominant mode of weather fluctuation originating in the tropics.

Seafloor

It is known that climate affects the ocean and the ocean affects the climate. Due to climate change, as the ocean gets warmer this too has an effect on the seafloor. Because of greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide, this warming will have an effect on the bicarbonate buffer of the ocean. The bicarbonate buffer is the concentration of bicarbonate ions that keeps the ocean's acidity balanced within a pH range of 7.5–8.4. Addition of carbon dioxide to the ocean water makes the oceans more acidic. Increased ocean acidity is not good for the planktonic organisms that depend on calcium to form their shells. Calcium dissolves with very weak acids and any increase in the ocean's acidity will be destructive for the calcareous organisms. Increased ocean acidity will lead to decreased Calcite Compensation Depth (CCD), causing calcite to dissolve in shallower waters. This will then have a great effect on the calcareous ooze in the ocean, because the sediment itself would begin to dissolve.

Predictions

A temperature rise of 1.5°C above preindustrial levels is projected to make existence impossible for 10% of fishes in their typical geographical range. A temperature rise of 5°C above this level is projected to make existence impossible for 60% of fishes in their geographical range. The main reason is Oxygen depletion as one of the consequences of the rise in temperature. Further, the change in temperature and decrease in oxygen is expected to occur too quickly for effective adaptation of affected species. Fishes can migrate to cooler places, but there are not always appropriate spawning sites.

If ocean temperatures rise it will have an effect right beneath the ocean floor and it will allow the addition of another greenhouse gas, methane gas. Methane gas has been found under methane hydrate, frozen methane and water, beneath the ocean floor. With the ocean warming, this methane hydrate will begin to melt and release methane gas, contributing to global warming. However, recent research has found that CO2 uptake outpaces methane release in these areas of the ocean causing overall decreases in global warming. Increase of water temperature will also have a devastating effect on different oceanic ecosystems like coral reefs. The direct effect is the coral bleaching of these reefs, which live within a narrow temperature margin, so a small increase in temperature would have a drastic effects in these environments. When corals bleach it is because the coral loses 60–90% of their zooxanthellae due to various stressors, ocean temperature being one of them. If the bleaching is prolonged, the coral host would die.

Although uncertain, another effect of climate change may be the growth, toxicity, and distribution of harmful algal blooms. These algal blooms have serious effects on not only marine ecosystems, killing sea animals and fish with their toxins, but also for humans as well. Some of these blooms deplete the oxygen around them to levels low enough to kill fish.