First edition cover | |

| Author | George Orwell |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Michael Kennar |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Dystopian, political fiction, social science fiction |

| Set in | London, Airstrip One, Oceania |

| Publisher | Secker & Warburg |

Publication date | 8 June 1949 |

| Media type | Print (hardback and paperback) |

| Pages | 328 |

| OCLC | 470015866 |

| 823.912 | |

| Preceded by | Animal Farm |

Nineteen Eighty-Four (also stylised as 1984) is a dystopian social science fiction novel and cautionary tale written by English writer George Orwell. It was published on 8 June 1949 by Secker & Warburg as Orwell's ninth and final book completed in his lifetime. Thematically, it centres on the consequences of totalitarianism, mass surveillance and repressive regimentation of people and behaviours within society. Orwell, a democratic socialist, modelled the totalitarian government in the novel after Stalinist Russia and Nazi Germany. More broadly, the novel examines the role of truth and facts within politics and the ways in which they are manipulated.

The story takes place in an imagined future, the year 1984, when much of the world has fallen victim to perpetual war, omnipresent government surveillance, historical negationism, and propaganda. Great Britain, known as Airstrip One, has become a province of the totalitarian superstate Oceania, ruled by the Party, who employ the Thought Police to persecute individuality and independent thinking. Big Brother, the dictatorial leader of Oceania, enjoys an intense cult of personality, manufactured by the party's excessive brainwashing techniques. The protagonist, Winston Smith, is a diligent and skillful rank-and-file worker and Outer Party member who secretly hates the Party and dreams of rebellion. He enters into a forbidden relationship with his colleague Julia and starts to remember what life was like before the Party came to power.

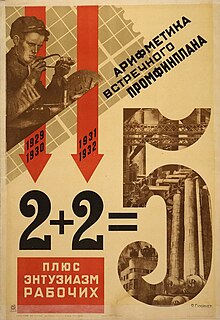

Nineteen Eighty-Four has become a classic literary example of political and dystopian fiction. It also popularised the term "Orwellian" as an adjective, with many terms used in the novel entering common usage, including "Big Brother", "doublethink", "Thought Police", "thoughtcrime", "Newspeak", and "2 + 2 = 5". Parallels have been drawn between the novel's subject matter and real life instances of totalitarianism, mass surveillance, and violations of freedom of expression among other themes. Time included the novel on its list of the 100 best English-language novels from 1923 to 2005, and it was placed on the Modern Library's 100 Best Novels list, reaching number 13 on the editors' list and number 6 on the readers' list. In 2003, it was listed at number eight on The Big Read survey by the BBC.

Background and title

In 1944, Orwell began work which "encapsulate[d] the thesis at the heart of his... novel", which explored the consequences of dividing the world up into zones of influence, as conjured by the recent Tehran Conference. Three years later, he wrote most of the actual book on the Scottish island of Jura from 1947 to 1948 despite being seriously ill with tuberculosis. On 4 December 1948, he sent the final manuscript to the publisher Secker and Warburg, and Nineteen Eighty-Four was published on 8 June 1949.

The Last Man in Europe was an early title for the novel, but in a letter dated 22 October 1948 to his publisher Fredric Warburg, eight months before publication, Orwell wrote about hesitating between that title and Nineteen Eighty-Four. Warburg suggested choosing the latter, which he took to be a more commercially viable choice for the main title.

The introduction to the Houghton Mifflin Harcourt edition of Animal Farm and 1984 (2003) claims that the title 1984 was chosen simply as an inversion of the year 1948, the year in which it was being completed, and that the date was meant to give an immediacy and urgency to the menace of totalitarian rule. This is disputed:

There's a very popular theory—so popular that many people don't realize it is just a theory—that Orwell's title was simply a satirical inversion of 1948, but there is no evidence for this whatsoever. This idea, first suggested by Orwell's US publisher, seems far too cute for such a serious book. [...] Scholars have raised other possibilities. [His wife] Eileen wrote a poem for her old school's centenary called "End of the Century: 1984." G. K. Chesterton's 1904 political satire The Napoleon of Notting Hill, which mocks the art of prophecy, opens in 1984. The year is also a significant date in The Iron Heel. But all of these connections are exposed as no more than coincidences by the early drafts of the novel Orwell was still calling The Last Man in Europe. First he wrote 1980, then 1982, and only later 1984. The most fateful date in literature was a late amendment.

— Dorian Lynskey, The Ministry of Truth: The Biography of George Orwell's 1984 (2019)

Throughout its publication history, Nineteen Eighty-Four has been either banned or legally challenged as subversive or ideologically corrupting, like the dystopian novels We (1924) by Yevgeny Zamyatin, Brave New World (1932) by Aldous Huxley, Darkness at Noon (1940) by Arthur Koestler, Kallocain (1940) by Karin Boye, and Fahrenheit 451 (1953) by Ray Bradbury.

Some writers consider Zamyatin's We to have influenced Nineteen Eighty-Four. The novel also bears significant similarities in plot and characters to Koestler's Darkness at Noon, which Orwell had reviewed and highly praised.

The original manuscript for Nineteen Eighty-Four is Orwell's only surviving literary manuscript. It is presently held at the John Hay Library at Brown University.

Plot

In 1984, civilisation has been ravaged by world war, civil conflict, and revolution. Airstrip One (formerly known as Great Britain) is a province of Oceania, one of the three totalitarian super-states that rule the world. It is ruled by "The Party" under the ideology of "Ingsoc" (a Newspeak shortening of "English Socialism") and the mysterious leader Big Brother, who has an intense cult of personality. The Party brutally purges out anyone who does not fully conform to their regime using the Thought Police and constant surveillance through telescreens (two-way televisions), cameras, and hidden microphones. Those who fall out of favour with the Party become "unpersons", disappearing with all evidence of their existence destroyed.

In London, Winston Smith is a member of the Outer Party, working at the Ministry of Truth, where he rewrites historical records to conform to the state's ever-changing version of history. Winston revises past editions of The Times, while the original documents are destroyed after being dropped into ducts leading to the memory hole. He secretly opposes the Party's rule and dreams of rebellion, despite knowing that he is already a "thoughtcriminal" and is likely to be caught one day.

While in a prole (Proletariat) neighbourhood, he meets Mr. Charrington, the owner of an antiques shop, and buys a diary where he writes criticisms of the Party and Big Brother. To his dismay, when he visits a prole quarter he discovers they have no political consciousness. As he works in the Ministry of Truth, he observes Julia, a young woman maintaining the novel-writing machines at the ministry, whom Winston suspects of being a spy, and develops an intense hatred of her. He vaguely suspects that his superior, an Inner Party official O'Brien, is part of an enigmatic underground resistance movement known as the Brotherhood, formed by Big Brother's reviled political rival Emmanuel Goldstein.

One day, Julia secretly hands Winston a love note, and the two begin a secret affair. Julia explains that she also loathes the Party, but Winston observes that she is politically apathetic and uninterested in overthrowing the regime. Initially meeting in the country, they later meet in a rented room above Mr. Charrington's shop. During the affair, Winston remembers the disappearance of his family during the civil war of the 1950s and his tense relationship with his estranged wife Katharine. Weeks later, O'Brien invites Winston to his flat, where he introduces himself as a member of the Brotherhood and sends Winston a copy of The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism by Goldstein. Meanwhile, during the nation's Hate Week, Oceania's enemy suddenly changes from Eurasia to Eastasia, which goes mostly unnoticed. Winston is recalled to the Ministry to help make the necessary revisions of the records. Winston and Julia read parts of Goldstein's book, which explains how the Party maintains power, the true meanings of its slogans, and the concept of perpetual war. It argues that the Party can be overthrown if proles rise up against it. However, Winston feels that it does not answer 'why' the Party is motivated to maintain power.

Winston and Julia are captured when Mr. Charrington is revealed to be a Thought Police agent, and imprisoned at the Ministry of Love. O'Brien arrives, also revealing himself as a Thought Police agent. O'Brien tells Winston that he will never know whether the Brotherhood actually exists and that Emmanuel Goldstein's book was written collaboratively by O'Brien and other Party members. Over several months, Winston is starved and tortured to bring his beliefs in line with the Party. O'Brien reveals that the Party "seeks power for its own sake."

O'Brien takes Winston to Room 101 for the final stage of re-education, which contains each prisoner's worst fear. When confronted with a cage holding frenzied rats, Winston betrays Julia by wishing the torture upon her instead. Winston is released back into public life and continues to frequent the Chestnut Tree Café. One day, Winston encounters Julia, who was also tortured. Both reveal that they have betrayed the other and no longer have feelings for each other. Back in the café, a news alert celebrates Oceania's supposed massive victory over Eurasian armies in Africa. Winston finally accepts that he loves Big Brother.

Characters

Main characters

- Winston Smith – the protagonist who is a phlegmatic everyman and is curious about the past before the Revolution.

- Julia – Winston's lover who is a covert "rebel from the waist downwards" who publicly espouses Party doctrine as a member of the fanatical Junior Anti-Sex League.

- O'Brien – a member of the Inner Party who poses as a member of The Brotherhood, the counter-revolutionary resistance, a spy intending to deceive, trap, and capture Winston and Julia. O'Brien has a servant named Martin.

Secondary characters

- Aaronson, Jones, and Rutherford – former members of the Inner Party whom Winston vaguely remembers as among the original leaders of the Revolution, long before he had heard of Big Brother. They confessed to treasonable conspiracies with foreign powers and were then executed in the political purges of the 1960s. In between their confessions and executions, Winston saw them drinking in the Chestnut Tree Café—with broken noses, suggesting that their confessions had been obtained by torture. Later, in the course of his editorial work, Winston sees newspaper evidence contradicting their confessions, but drops it into a memory hole. Eleven years later, he is confronted with the same photograph during his interrogation.

- Ampleforth – Winston's one-time Records Department colleague who was imprisoned for leaving the word "God" in a Kipling poem as he could not find another rhyme for "rod"; Winston encounters him at the Miniluv. Ampleforth is a dreamer and intellectual who takes pleasure in his work, and respects poetry and language, traits which cause him disfavour with the Party.

- Charrington – an officer of the Thought Police posing as a sympathetic antiques dealer amongst the proles.

- Katharine Smith – the emotionally indifferent wife whom Winston "can't get rid of". Despite disliking sexual intercourse, Katharine married Winston because it was their "duty to the Party". Although she was a "goodthinkful" ideologue, they separated because the couple could not conceive children. Divorce is not permitted, but couples who cannot have children may live separately. For much of the story Winston lives in vague hope that Katharine may die or could be "got rid of" so that he may marry Julia. He regrets not having killed her by pushing her over the edge of a quarry when he had the chance many years previously.

- Tom Parsons – Winston's naïve neighbour, and an ideal member of the Outer Party: an uneducated, suggestible man who is utterly loyal to the Party, and fully believes in its perfect image. He is socially active and participates in the Party activities for his social class. He is friendly towards Smith, and despite his political conformity punishes his bullying son for firing a catapult at Winston. Later, as a prisoner, Winston sees Parsons is in the Ministry of Love, as his daughter had reported him to the Thought Police, saying she heard him speak against Big Brother in his sleep. Even this does not dampen his belief in the Party, and he states he could do "good work" in the hard labour camps.

- Mrs. Parsons – Parsons's wife is a wan and hapless woman who is intimidated by her own children.

- The Parsons children – a nine-year-old son and seven-year-old daughter. Both are members of the Spies, a youth organization that focuses on indoctrinating children with Party ideals and training them to report any suspected incidents of unorthodoxy. They represent the new generation of Oceanian citizens, without memory of life before Big Brother, and without family ties or emotional sentiment; the model society envisioned by the Inner Party.

- Syme – Winston's colleague at the Ministry of Truth, a lexicographer involved in compiling a new edition of the Newspeak dictionary. Although he is enthusiastic about his work and support for the Party, Winston notes, "He is too intelligent. He sees too clearly and speaks too plainly." Winston predicts, correctly, that Syme will become an unperson.

Additionally, the following characters, mentioned in the novel, play a significant role in the world-building of 1984. Whether these characters are real or fabrications of Party propaganda is something that neither Winston nor the reader is permitted to know:

- Big Brother – the leader and figurehead of the Party that rules Oceania. A deep cult of personality is formed around him.

- Emmanuel Goldstein – ostensibly a former leading figure in the Party who became the counter-revolutionary leader of the Brotherhood, and author of the book The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism. Goldstein is the symbolic enemy of the state—the national nemesis who ideologically unites the people of Oceania with the Party, especially during the Two Minutes Hate and other forms of fearmongering.

Setting

History of the world

The Revolution

Many of Orwell's earlier writings clearly indicate that he originally welcomed the prospect of a Socialist revolution in the UK, and indeed hoped to himself take part in such a revolution. The concept of "English Socialism" first appeared in Orwell's 1941 "The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius", where Orwell outlined a relatively humane revolution — establishing a revolutionary regime which "will shoot traitors, but give them a solemn trial beforehand, and occasionally acquit them" and which "will crush any open revolt promptly and cruelly, but will interfere very little with the spoken and written word"; the "English Socialism" which Orwell foresaw in 1941 would even "abolish the House of Lords, but retain the Monarchy". However, at some time between 1941 and 1948 Orwell evidently became disillusioned and came to the conclusion that also his cherished English Socialism would be perverted into an oppressive totalitarian dictatorship, as bad as Stalin's Soviet Union. Such is the revolution described in Nineteen Eighty-Four.

Winston Smith's memories and his reading of the proscribed book, The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism by Emmanuel Goldstein, reveal that after the Second World War, the United Kingdom became involved in a war during the early 1950s in which nuclear weapons destroyed hundreds of cities in Europe, western Russia and North America. Colchester was destroyed, and London also suffered widespread aerial raids, leading Winston's family to take refuge in a London Underground station. The United States absorbed the British Commonwealth and Latin America, resulting in the superstate of Oceania. The new nation fell into civil war, but who fought whom is left unclear (there is a reference to the child Winston having seen rival militias in the streets, each one having a shirt of a distinct color for its members). It is also unclear what The Party's name was while there were more than one, and whether it was a radical faction of the British Labour Party or a new formation arising during the turbulent 1950s. Eventually, Ingsoc won and gradually formed a totalitarian government across Oceania. Another point left completely unexplained is how the US came to regard "English Socialism" as its ruling ideology; while a Socialist revolution in the UK was a concrete possibility, taken seriously for much of the Twentieth Century, in the United States Socialism of any kind had always been a marginal phenomenon.

Meanwhile, Eurasia was formed when the Soviet Union conquered Mainland Europe, creating a single state stretching from Portugal to the Bering Strait, under a Neo-Stalinist regime. In effect, the situation of 1940–1944 — the UK facing an enemy-held Europe across the Channel — was recreated, and this time permanently — neither side contemplating an invasion, their wars held in other parts of the world. Eastasia, the last superstate established, emerged only after "a decade of confused fighting". It includes the Asian lands conquered by China and Japan. (The book was written before the 1949 victory of Mao Tse-tung's Chinese Communist Party in the Civil War). Although Eastasia is prevented from matching Eurasia's size, its larger populace compensates for that handicap.

While citizens in each state are trained to despise the ideologies of the other two as uncivilised and barbarous, Goldstein's book explains that in fact the superstates' ideologies are practically identical and that the public's ignorance of this fact is imperative so that they might continue believing otherwise. The only references to the exterior world for the Oceanian citizenry are propaganda and (probably fake) maps fabricated by the Ministry of Truth to ensure people's belief in "the war".

However, due to the fact that Winston only barely remembers these events as well as the Party's constant manipulation of historical records, the continuity and accuracy of these events are unknown, and exactly how the superstates' ruling parties managed to gain their power is also left unclear. Winston notes that the Party has claimed credit for inventing helicopters and aeroplanes, while Julia theorises that the perpetual bombing of London is merely a false-flag operation designed to convince the populace that a war is occurring. If the official account was accurate, Smith's strengthening memories and the story of his family's dissolution suggest that the atomic bombings occurred first, followed by civil war featuring "confused street fighting in London itself" and the societal postwar reorganisation, which the Party retrospectively calls "the Revolution".

It is very difficult to trace the exact chronology, but most of the global societal reorganisation occurred between 1945 and the early 1960s. Winston and Julia meet in the ruins of a church that was destroyed in a nuclear attack "thirty years" earlier, which suggests 1954 as the year of the atomic war that destabilised society and allowed the Party to seize power. It is stated in the novel that the "fourth quarter of 1983" was "also the sixth quarter of the Ninth Three-Year Plan", which implies that the first three-year plan began in 1958. By that same year, the Party had apparently gained control of Oceania.

Among other things, the Revolution completely obliterates all religion. While the underground "Brotherhood" might or might not exist, there is no suggestion of any clergy trying to keep any religion alive underground. It is noted that, since the Party does not really care what the proles think or do, they might have been permitted to have religious worship had they wanted to — but they show no such inclination. Among the manifestly absurd "confessions" extracted from "thought criminals" they have to admit being a religious believer — however, no one takes this seriously. Churches have been demolished or converted to other uses — St Martin-in-the-Fields had become a military museum, while Saint Clement Danes, destroyed in a WWII bombing, was in this future simply never rebuilt. The idea of a revolutionary regime totally destroying religion, with relative ease, is shared with the otherwise very different future of H.G.Wells' The Shape of Things to Come.

The War

In 1984, there is a perpetual war between Oceania, Eurasia and Eastasia, the superstates that emerged from the global atomic war. The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism, by Emmanuel Goldstein, explains that each state is so strong that it cannot be defeated, even with the combined forces of two superstates, despite changing alliances. To hide such contradictions, the superstates' governments rewrite history to explain that the (new) alliance always was so; the populaces are already accustomed to doublethink and accept it. The war is not fought in Oceanian, Eurasian or Eastasian territory but in the Arctic wastes and a disputed zone comprising the sea and land from Tangiers (Northern Africa) to Darwin (Australia). At the start, Oceania and Eastasia are allies fighting Eurasia in northern Africa and the Malabar Coast.

That alliance ends, and Oceania, allied with Eurasia, fights Eastasia, a change occurring on Hate Week, dedicated to creating patriotic fervour for the Party's perpetual war. The public are blind to the change; in mid-sentence, an orator changes the name of the enemy from "Eurasia" to "Eastasia" without pause. When the public are enraged at noticing that the wrong flags and posters are displayed, they tear them down; the Party later claims to have captured the whole of Africa.

Goldstein's book explains that the purpose of the unwinnable, perpetual war is to consume human labour and commodities so that the economy of a superstate cannot support economic equality, with a high standard of life for every citizen. By using up most of the produced goods, the proles are kept poor and uneducated, and the Party hopes that they will neither realise what the government is doing nor rebel. Goldstein also details an Oceanian strategy of attacking enemy cities with atomic rockets before invasion but dismisses it as unfeasible and contrary to the war's purpose; despite the atomic bombing of cities in the 1950s, the superstates stopped it for fear that it would imbalance the powers. The military technology in the novel differs little from that of World War II, but strategic bomber aeroplanes are replaced with rocket bombs, helicopters were heavily used as weapons of war (they did not figure in World War II in any form but prototypes) and surface combat units have been all but replaced by immense and unsinkable Floating Fortresses (island-like contraptions concentrating the firepower of a whole naval task force in a single, semi-mobile platform; in the novel, one is said to have been anchored between Iceland and the Faroe Islands, suggesting a preference for sea lane interdiction and denial).

Claude Rozenhof notes that:

None of the war news in Nineteen Eighty-Four can be in any way trusted as a report of something which actually happened (within the frame of the book's plot). Winston Smith himself is depicted as inventing a war hero who never existed and attributing to him various acts which never took place. After Oceania's shift of alliance, fighting Eastasia rather than Eurasia, the entire Ministry of Truth staff is engaged in an intensive effort to eradicate all reports of the war with Eurasia and "move the war to another part of the world" — so we do know for a fact that all records of the previous five years of war are henceforward false, depicting battles which never happened in places where there had been no war — but it might well be that the earlier records of a war with Eurasia, which were destroyed and eradicated, had been just as false.(...) The same doubts apply also to the major piece of war news in the final chapter — a titanic battle engulfing the entire continent of Africa, won by Oceania due to a brilliant piece of strategic surprise and finally proving to Smith the genius of Big Brother. There is no way of knowing whether any such battle "really" took place in Africa. Nor can we know if this piece of spectacular war news was broadcast all over Oceania, or whether it was an exclusive "show" broadcast solely into the telescreen in the Chestnut Tree Cafe, with the sole purpose of having on Winston Smith exactly the psychological effect which it did have. Indeed, there is the passage where Julia doubts that any war is taking place at all, and suspects that the rockets falling occasionally on London are fired by the government of Oceania itself, to keep the population on their toes — though Winston does not let his doubts of the official propaganda go that far. (...) And how much can we, living in a supposedly free and democratic society, objectively check the verity of what our supposedly Free press tells us?

Political geography

Three perpetually warring totalitarian superstates control the world in the novel:

- Oceania (ideology: Ingsoc, known in Oldspeak as English Socialism), whose core territories are "the Americas, the Atlantic Islands, including the British Isles, Australasia and the southern portion of Africa."

- Eurasia (ideology: Neo-Bolshevism), whose core territories are "the whole of the northern part of the European and Asiatic landmass from Portugal to the Bering Strait."

- Eastasia (ideology: Obliteration of the Self, also known as Death-Worship), whose core territories are "China and the countries south to it, the Japanese islands, and a large but fluctuating portion of Manchuria, Mongolia and Tibet."

The perpetual war is fought for control of the "disputed area" lying between the frontiers of the superstates, which forms "a rough quadrilateral with its corners at Tangier, Brazzaville, Darwin and Hong Kong", which includes Equatorial Africa, the Middle East, India and Indonesia. The disputed area is where the superstates capture slave labour. Fighting also takes place between Eurasia and Eastasia in Manchuria, Mongolia and Central Asia, and between Eurasia and Oceania over various islands in the Indian and Pacific Ocean.

Oceania

Ingsoc (English Socialism) is the predominant ideology and philosophy of Oceania, and Newspeak is the official language of official documents. Orwell depicts the Party's ideology as an oligarchical worldview that "rejects and vilifies every principle for which the Socialist movement originally stood, and it does so in the name of Socialism."

Ministries of Oceania

In London, the capital city of Airstrip One, Oceania's four government ministries are in pyramids (300 m high), the façades of which display the Party's three slogans - "WAR IS PEACE", "FREEDOM IS SLAVERY", "IGNORANCE IS STRENGTH". As mentioned, the ministries are deliberately named after the opposite (doublethink) of their true functions: "The Ministry of Peace concerns itself with war, the Ministry of Truth with lies, the Ministry of Love with torture and the Ministry of Plenty with starvation." (Part II, Chapter IX – The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism).

While a ministry is supposedly headed by a minister, the ministers heading these four ministries are never mentioned. They seem to be completely out of the public view, Big Brother being the only, ever-present public face of the government.

Ministry of Peace

The Ministry of Peace supports Oceania's perpetual war against either of the two other superstates:

The primary aim of modern warfare (in accordance with the principles of doublethink, this aim is simultaneously recognised and not recognised by the directing brains of the Inner Party) is to use up the products of the machine without raising the general standard of living. Ever since the end of the nineteenth century, the problem of what to do with the surplus of consumption goods has been latent in industrial society. At present, when few human beings even have enough to eat, this problem is obviously not urgent, and it might not have become so, even if no artificial processes of destruction had been at work.

Ministry of Plenty

The Ministry of Plenty rations and controls food, goods, and domestic production; every fiscal quarter, it claims to have raised the standard of living, even during times when it has, in fact, reduced rations, availability, and production. The Ministry of Truth substantiates the Ministry of Plenty's claims by manipulating historical records to report numbers supporting the claims of "increased rations". The Ministry of Plenty also runs the national lottery as a distraction for the proles; Party members understand it to be a sham process in which winnings are never paid out.

Ministry of Truth

The Ministry of Truth controls information: news, entertainment, education, and the arts. Winston Smith works in the Records Department, "rectifying" historical records to accord with Big Brother's current pronouncements so that everything the Party says appears to be true.

Ministry of Love

The Ministry of Love identifies, monitors, arrests and converts real and imagined dissidents. This is also the place where the Thought Police beat and torture dissidents, after which they are sent to Room 101 to face "the worst thing in the world"—until love for Big Brother and the Party replaces dissension.

Major concepts

Big Brother

The Big Brother is a fictional character and symbol in the novel. He is ostensibly the leader of Oceania, a totalitarian state wherein the ruling party Ingsoc wields total power "for its own sake" over the inhabitants. In the society that Orwell describes, every citizen is under constant surveillance by the authorities, mainly by telescreens (with the exception of the proles). The people are constantly reminded of this by the slogan "Big Brother is watching you": a maxim that is ubiquitously on display.

In modern culture, the term "Big Brother" has entered the lexicon as a synonym for abuse of government power, particularly in respect to civil liberties, often specifically related to mass surveillance.

Doublethink

The keyword here is blackwhite. Like so many Newspeak words, this word has two mutually contradictory meanings. Applied to an opponent, it means the habit of impudently claiming that black is white, in contradiction of the plain facts. Applied to a Party member, it means a loyal willingness to say that black is white when Party discipline demands this. But it means also the ability to believe that black is white, and more, to know that black is white, and to forget that one has ever believed the contrary. This demands a continuous alteration of the past, made possible by the system of thought which really embraces all the rest, and which is known in Newspeak as doublethink. Doublethink is basically the power of holding two contradictory beliefs in one's mind simultaneously, and accepting both of them.

— Part II, Chapter IX – The Theory and Practice of Oligarchical Collectivism

Newspeak

The Principles of Newspeak is an academic essay appended to the novel. It describes the development of Newspeak, an artificial, minimalistic language designed to ideologically align thought with the principles of Ingsoc by stripping down the English language in order to make the expression of "heretical" thoughts (i.e. thoughts going against Ingsoc's principles) impossible. The idea that a language's structure can be used to influence thought is known as linguistic relativity.

Whether or not the Newspeak appendix implies a hopeful end to Nineteen Eighty-Four remains a critical debate. Many claim that it does, citing the fact that it is in standard English and is written in the past tense: "Relative to our own, the Newspeak vocabulary was tiny, and new ways of reducing it were constantly being devised" (p. 422). Some critics (Atwood, Benstead, Milner, Pynchon) claim that for Orwell, Newspeak and the totalitarian governments are all in the past.

Thoughtcrime

Thoughtcrime describes a person's politically unorthodox thoughts, such as unspoken beliefs and doubts that contradict the tenets of Ingsoc (English Socialism), the dominant ideology of Oceania. In the official language of Newspeak, the word crimethink describes the intellectual actions of a person who entertains and holds politically unacceptable thoughts; thus the government of the Party controls the speech, the actions, and the thoughts of the citizens of Oceania. In contemporary English usage, the word thoughtcrime describes beliefs that are contrary to accepted norms of society, and is used to describe theological concepts, such as disbelief and idolatry, and the rejection of an ideology.

Themes

Nationalism

Nineteen Eighty-Four expands upon the subjects summarised in Orwell's essay "Notes on Nationalism" about the lack of vocabulary needed to explain the unrecognised phenomena behind certain political forces. In Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Party's artificial, minimalist language 'Newspeak' addresses the matter.

- Positive nationalism: For instance, Oceanians' perpetual love for Big Brother. Orwell argues in the essay that ideologies such as Neo-Toryism and Celtic nationalism are defined by their obsessive sense of loyalty to some entity.

- Negative nationalism: For instance, Oceanians' perpetual hatred for Emmanuel Goldstein. Orwell argues in the essay that ideologies such as Trotskyism and Antisemitism are defined by their obsessive hatred of some entity.

- Transferred nationalism: For instance, when Oceania's enemy changes, an orator makes a change mid-sentence, and the crowd instantly transfers its hatred to the new enemy. Orwell argues that ideologies such as Stalinism and redirected feelings of racial animus and class superiority among wealthy intellectuals exemplify this. Transferred nationalism swiftly redirects emotions from one power unit to another. In the novel, it happens during Hate Week, a Party rally against the original enemy. The crowd goes wild and destroys the posters that are now against their new friend, and many say that they must be the act of an agent of their new enemy and former friend. Many of the crowd must have put up the posters before the rally but think that the state of affairs had always been the case.

O'Brien concludes: "The object of persecution is persecution. The object of torture is torture. The object of power is power."

Futurology

In the book, Inner Party member O'Brien describes the Party's vision of the future:

There will be no curiosity, no enjoyment of the process of life. All competing pleasures will be destroyed. But always—do not forget this, Winston—always there will be the intoxication of power, constantly increasing and constantly growing subtler. Always, at every moment, there will be the thrill of victory, the sensation of trampling on an enemy who is helpless. If you want a picture of the future, imagine a boot stamping on a human face—forever.

— Part III, Chapter III, Nineteen Eighty-Four

Censorship

One of the most notable themes in Nineteen Eighty-Four is censorship, especially in the Ministry of Truth, where photographs and public archives are manipulated to rid them of "unpersons" (people who have been erased from history by the Party). On the telescreens, almost all figures of production are grossly exaggerated or simply fabricated to indicate an ever-growing economy, even during times when the reality is the opposite. One small example of the endless censorship is Winston being charged with the task of eliminating a reference to an unperson in a newspaper article. He also proceeds to write an article about Comrade Ogilvy, a made-up party member who allegedly "displayed great heroism by leaping into the sea from a helicopter so that the dispatches he was carrying would not fall into enemy hands."

Surveillance

In Oceania, the upper and middle classes have very little true privacy. All of their houses and apartments are equipped with telescreens so that they may be watched or listened to at any time. Similar telescreens are found at workstations and in public places, along with hidden microphones. Written correspondence is routinely opened and read by the government before it is delivered. The Thought Police employ undercover agents, who pose as normal citizens and report any person with subversive tendencies. Children are encouraged to report suspicious persons to the government, and some denounce their parents. Citizens are controlled, and the smallest sign of rebellion, even something as small as a suspicious facial expression, can result in immediate arrest and imprisonment. Thus, citizens are compelled to obedience.

Poverty and inequality

According to Goldstein's book, almost the entire world lives in poverty; hunger, thirst, disease, and filth are the norms. Ruined cities and towns are common: the consequence of wars and false flag operations. Social decay and wrecked buildings surround Winston; aside from the ministries' pyramids, little of London was rebuilt. Middle class citizens and proles consume synthetic foodstuffs and poor-quality "luxuries" such as oily gin and loosely-packed cigarettes, distributed under the "Victory" brand, a parody of the low-quality Indian-made "Victory" cigarettes, widely smoked in Britain and by British soldiers during World War II.

Winston describes something as simple as the repair of a broken window as requiring committee approval that can take several years and so most of those living in one of the blocks usually do the repairs themselves (Winston himself is called in by Mrs. Parsons to repair her blocked sink). All upper-class and middle-class residences include telescreens that serve both as outlets for propaganda and surveillance devices that allow the Thought Police to monitor them; they can be turned down, but the ones in middle-class residences cannot be turned off.

In contrast to their subordinates, the upper class of Oceanian society reside in clean and comfortable flats in their own quarters, with pantries well-stocked with foodstuffs such as wine, real coffee, real tea, real milk, and real sugar, all denied to the general populace. Winston is astonished that the lifts in O'Brien's building work, the telescreens can be completely turned off, and O'Brien has an Asian manservant, Martin. All upper class citizens are attended to by slaves captured in the "disputed zone", and "The Book" suggests that many have their own cars or even helicopters. Nonetheless, "The Book" makes clear that even the conditions enjoyed by the Inner Party are only "relatively" comfortable, and standards would be regarded as austere by those of the pre-revolutionary élite.

The proles live in poverty and are kept sedated with alcohol, pornography, and a national lottery whose winnings are rarely paid out; which fact is obscured by propaganda and the lack of communication within Oceania. At the same time, the proles are freer and less intimidated than the upper classes: they are not expected to be particularly patriotic and the levels of surveillance that they are subjected to are very low. They lack telescreens in their own homes and often jeer at the telescreens that they see. "The Book" indicates that because the middle class, not the lower class, traditionally starts revolutions, the model demands tight control of the middle class, with ambitious Outer-Party members neutralised via promotion to the Inner Party or "reintegration" by the Ministry of Love, and proles can be allowed intellectual freedom because they are deemed to lack intellect. Winston nonetheless believes that "the future belonged to the proles".

The standard of living of the populace is extremely low overall. Consumer goods are scarce, and those available through official channels are of low quality; for instance, despite the Party regularly reporting increased boot production, more than half of the Oceanian populace goes barefoot. The Party claims that poverty is a necessary sacrifice for the war effort, and "The Book" confirms that to be partially correct since the purpose of perpetual war is to consume surplus industrial production.

Sources for literary motifs

Nineteen Eighty-Four uses themes from life in the Soviet Union and wartime life in Great Britain as sources for many of its motifs. Some time at an unspecified date after the first American publication of the book, producer Sidney Sheldon wrote to Orwell interested in adapting the novel to the Broadway stage. Orwell sold the American stage rights to Sheldon, explaining that his basic goal with Nineteen Eighty-Four was imagining the consequences of Stalinist government ruling British society:

[Nineteen Eighty-Four] was based chiefly on communism, because that is the dominant form of totalitarianism, but I was trying chiefly to imagine what communism would be like if it were firmly rooted in the English speaking countries, and was no longer a mere extension of the Russian Foreign Office.

According to Orwell biographer D. J. Taylor, the author's A Clergyman's Daughter (1935) has "essentially the same plot of Nineteen Eighty-Four ... It's about somebody who is spied upon, and eavesdropped upon, and oppressed by vast exterior forces they can do nothing about. It makes an attempt at rebellion and then has to compromise".

The statement "2 + 2 = 5", used to torment Winston Smith during his interrogation, was a communist party slogan from the second five-year plan, which encouraged fulfilment of the five-year plan in four years. The slogan was seen in electric lights on Moscow house-fronts, billboards and elsewhere.

The switch of Oceania's allegiance from Eastasia to Eurasia and the subsequent rewriting of history ("Oceania was at war with Eastasia: Oceania had always been at war with Eastasia. A large part of the political literature of five years was now completely obsolete"; ch 9) is evocative of the Soviet Union's changing relations with Nazi Germany. The two nations were open and frequently vehement critics of each other until the signing of the 1939 Treaty of Non-Aggression. Thereafter, and continuing until the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941, no criticism of Germany was allowed in the Soviet press, and all references to prior party lines stopped—including in the majority of non-Russian communist parties who tended to follow the Russian line. Orwell had criticised the Communist Party of Great Britain for supporting the Treaty in his essays for Betrayal of the Left (1941). "The Hitler-Stalin pact of August 1939 reversed the Soviet Union's stated foreign policy. It was too much for many of the fellow-travellers like Gollancz [Orwell's sometime publisher] who had put their faith in a strategy of construction Popular Front governments and the peace bloc between Russia, Britain and France."

The description of Emmanuel Goldstein, with a "small, goatee beard", evokes the image of Leon Trotsky. The film of Goldstein during the Two Minutes Hate is described as showing him being transformed into a bleating sheep. This image was used in a propaganda film during the Kino-eye period of Soviet film, which showed Trotsky transforming into a goat. Goldstein's book is similar to Trotsky's highly critical analysis of the USSR, The Revolution Betrayed, published in 1936.

The omnipresent images of Big Brother, a man described as having a moustache, bears resemblance to the cult of personality built up around Joseph Stalin.

The news in Oceania emphasised production figures, just as it did in the Soviet Union, where record-setting in factories (by "Heroes of Socialist Labour") was especially glorified. The best known of these was Alexey Stakhanov, who purportedly set a record for coal mining in 1935.

The tortures of the Ministry of Love evoke the procedures used by the NKVD in their interrogations, including the use of rubber truncheons, being forbidden to put your hands in your pockets, remaining in brightly lit rooms for days, torture through the use of their greatest fear, and the victim being shown a mirror after their physical collapse.

The random bombing of Airstrip One is based on the Buzz bombs and the V-2 rocket, which struck England at random in 1944–1945.

The Thought Police is based on the NKVD, which arrested people for random "anti-soviet" remarks. The Thought Crime motif is drawn from Kempeitai, the Japanese wartime secret police, who arrested people for "unpatriotic" thoughts.

The confessions of the "Thought Criminals" Rutherford, Aaronson, and Jones are based on the show trials of the 1930s, which included fabricated confessions by prominent Bolsheviks Nikolai Bukharin, Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev to the effect that they were being paid by the Nazi government to undermine the Soviet regime under Leon Trotsky's direction.

The song "Under the Spreading Chestnut Tree" ("Under the spreading chestnut tree, I sold you, and you sold me") was based on an old English song called "Go no more a-rushing" ("Under the spreading chestnut tree, Where I knelt upon my knee, We were as happy as could be, 'Neath the spreading chestnut tree."). The song was published as early as 1891. The song was a popular camp song in the 1920s, sung with corresponding movements (like touching one's chest when singing "chest", and touching one's head when singing "nut"). Glenn Miller recorded the song in 1939.

The "Hates" (Two Minutes Hate and Hate Week) were inspired by the constant rallies sponsored by party organs throughout the Stalinist period. These were often short pep-talks given to workers before their shifts began (Two Minutes Hate), but could also last for days, as in the annual celebrations of the anniversary of the October revolution (Hate Week).

Orwell fictionalised "newspeak", "doublethink", and "Ministry of Truth" based on the Soviet press. In particular, he adapted Soviet ideological discourse constructed to ensure that public statements could not be questioned.

Winston Smith's job, "revising history" (and the "unperson" motif) are based on censorship of images in the Soviet Union, which airbrushed images of "fallen" people from group photographs and removed references to them in books and newspapers. In one well-known example, the Soviet encyclopaedia had an article about Lavrentiy Beria. When he fell in 1953, and was subsequently executed, institutes that had the encyclopaedia were sent an article about the Bering Strait, with instructions to paste it over the article about Beria.

Big Brother's "Orders of the Day" were inspired by Stalin's regular wartime orders, called by the same name. A small collection of the more political of these have been published (together with his wartime speeches) in English as "On the Great Patriotic War of the Soviet Union" By Joseph Stalin. Like Big Brother's Orders of the day, Stalin's frequently lauded heroic individuals, like Comrade Ogilvy, the fictitious hero Winston Smith invented to "rectify" (fabricate) a Big Brother Order of the day.

The Ingsoc slogan "Our new, happy life", repeated from telescreens, evokes Stalin's 1935 statement, which became a CPSU slogan, "Life has become better, Comrades; life has become more cheerful."

In 1940, Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges published "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius", which describes the invention by a "benevolent secret society" of a world that would seek to remake human language and reality along human-invented lines. The story concludes with an appendix describing the success of the project. Borges' story addresses similar themes of epistemology, language and history to 1984.

During World War II, Orwell believed that British democracy as it existed before 1939 would not survive the war. The question being "Would it end via Fascist coup d'état from above or via Socialist revolution from below?" Later, he admitted that events proved him wrong: "What really matters is that I fell into the trap of assuming that 'the war and the revolution are inseparable'."

Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) and Animal Farm (1945) share themes of the betrayed revolution, the individual's subordination to the collective, rigorously enforced class distinctions (Inner Party, Outer Party, proles), the cult of personality, concentration camps, Thought Police, compulsory regimented daily exercise, and youth leagues. Oceania resulted from the US annexation of the British Empire to counter the Asian peril to Australia and New Zealand. It is a naval power whose militarism venerates the sailors of the floating fortresses, from which battle is given to recapturing India, the "Jewel in the Crown" of the British Empire. Much of Oceanic society is based upon the USSR under Joseph Stalin—Big Brother. The televised Two Minutes Hate is ritual demonisation of the enemies of the State, especially Emmanuel Goldstein (viz Leon Trotsky). Altered photographs and newspaper articles create unpersons deleted from the national historical record, including even founding members of the regime (Jones, Aaronson, and Rutherford) in the 1960s purges (viz the Soviet Purges of the 1930s, in which leaders of the Bolshevik Revolution were similarly treated). A similar thing also happened during the French Revolution's Reign of Terror in which many of the original leaders of the Revolution were later put to death, for example Danton who was put to death by Robespierre, and then later Robespierre himself met the same fate.

In his 1946 essay "Why I Write", Orwell explains that the serious works he wrote since the Spanish Civil War (1936–39) were "written, directly or indirectly, against totalitarianism and for democratic socialism".[3][69] Nineteen Eighty-Four is a cautionary tale about revolution betrayed by totalitarian defenders previously proposed in Homage to Catalonia (1938) and Animal Farm (1945), while Coming Up for Air (1939) celebrates the personal and political freedoms lost in Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949). Biographer Michael Shelden notes Orwell's Edwardian childhood at Henley-on-Thames as the golden country; being bullied at St Cyprian's School as his empathy with victims; his life in the Indian Imperial Police in Burma and the techniques of violence and censorship in the BBC as capricious authority.

Other influences include Darkness at Noon (1940) and The Yogi and the Commissar (1945) by Arthur Koestler; The Iron Heel (1908) by Jack London; 1920: Dips into the Near Future by John A. Hobson; Brave New World (1932) by Aldous Huxley; We (1921) by Yevgeny Zamyatin which he reviewed in 1946; and The Managerial Revolution (1940) by James Burnham predicting perpetual war among three totalitarian superstates. Orwell told Jacintha Buddicom that he would write a novel stylistically like A Modern Utopia (1905) by H. G. Wells.

Extrapolating from World War II, the novel's pastiche parallels the politics and rhetoric at war's end—the changed alliances at the "Cold War's" (1945–91) beginning; the Ministry of Truth derives from the BBC's overseas service, controlled by the Ministry of Information; Room 101 derives from a conference room at BBC Broadcasting House; the Senate House of the University of London, containing the Ministry of Information is the architectural inspiration for the Minitrue; the post-war decrepitude derives from the socio-political life of the UK and the US, i.e., the impoverished Britain of 1948 losing its Empire despite newspaper-reported imperial triumph; and war ally but peace-time foe, Soviet Russia became Eurasia.

The term "English Socialism" has precedents in Orwell's wartime writings; in the essay "The Lion and the Unicorn: Socialism and the English Genius" (1941), he said that "the war and the revolution are inseparable... the fact that we are at war has turned Socialism from a textbook word into a realisable policy"—because Britain's superannuated social class system hindered the war effort and only a socialist economy would defeat Adolf Hitler. Given the middle class's grasping this, they too would abide socialist revolution and that only reactionary Britons would oppose it, thus limiting the force revolutionaries would need to take power. An English Socialism would come about which "will never lose touch with the tradition of compromise and the belief in a law that is above the State. It will shoot traitors, but it will give them a solemn trial beforehand and occasionally it will acquit them. It will crush any open revolt promptly and cruelly, but it will interfere very little with the spoken and written word."

In the world of Nineteen Eighty-Four, "English Socialism" (or "Ingsoc" in Newspeak) is a totalitarian ideology unlike the English revolution he foresaw. Comparison of the wartime essay "The Lion and the Unicorn" with Nineteen Eighty-Four shows that he perceived a Big Brother regime as a perversion of his cherished socialist ideals and English Socialism. Thus Oceania is a corruption of the British Empire he believed would evolve "into a federation of Socialist states, like a looser and freer version of the Union of Soviet Republics".

Critical reception

When it was first published, Nineteen Eighty-Four received critical acclaim. V. S. Pritchett, reviewing the novel for the New Statesman stated: "I do not think I have ever read a novel more frightening and depressing; and yet, such are the originality, the suspense, the speed of writing and withering indignation that it is impossible to put the book down." P. H. Newby, reviewing Nineteen Eighty-Four for The Listener magazine, described it as "the most arresting political novel written by an Englishman since Rex Warner's The Aerodrome." Nineteen Eighty-Four was also praised by Bertrand Russell, E. M. Forster and Harold Nicolson. On the other hand, Edward Shanks, reviewing Nineteen Eighty-Four for The Sunday Times, was dismissive; Shanks claimed Nineteen Eighty-Four "breaks all records for gloomy vaticination". C. S. Lewis was also critical of the novel, claiming that the relationship of Julia and Winston, and especially the Party's view on sex, lacked credibility, and that the setting was "odious rather than tragic". On 5 November 2019, the BBC named Nineteen Eighty-Four on its list of the 100 most influential novels.

Adaptations in other media

In the same year as the novel's publishing, a one-hour radio adaptation was aired on the United States' NBC radio network as part of the NBC University Theatre series. The first television adaptation appeared as part of CBS's Studio One series in September 1953. BBC Television broadcast an adaptation by Nigel Kneale in December 1954. The first feature film adaptation, 1984, was released in 1956. A second feature-length adaptation, Nineteen Eighty-Four, followed in 1984; it received critical acclaim for its reasonably faithful adaptation of the novel. The story has been adapted several other times to radio, television, and film; other media adaptations include theater (a musical and a play), opera, and ballet.

Translations

The first Simplified Chinese version was published in 1979. It was first available to the general public in China in 1985, as previously it was only in portions of libraries and bookstores open to a limited number of people. Amy Hawkins and Jeffrey Wasserstrom of The Atlantic stated in 2019 that the book is widely available in Mainland China for several reasons: the general public by and large no longer reads books; because the elites who do read books feel connected to the ruling party anyway; and because the Communist Party sees being too aggressive in blocking cultural products as a liability. The authors stated "It was—and remains—as easy to buy 1984 and Animal Farm in Shenzhen or Shanghai as it is in London or Los Angeles." They also stated that "The assumption is not that Chinese people can’t figure out the meaning of 1984, but that the small number of people who will bother to read it won’t pose much of a threat."

By 1989, Nineteen Eighty-Four had been translated into 65 languages, more than any other novel in English at that time.

Cultural impact

The effect of Nineteen Eighty-Four on the English language is extensive; the concepts of Big Brother, Room 101, the Thought Police, thoughtcrime, unperson, memory hole (oblivion), doublethink (simultaneously holding and believing contradictory beliefs) and Newspeak (ideological language) have become common phrases for denoting totalitarian authority. Doublespeak and groupthink are both deliberate elaborations of doublethink, and the adjective "Orwellian" means similar to Orwell's writings, especially Nineteen Eighty-Four. The practice of ending words with "-speak" (such as mediaspeak) is drawn from the novel. Orwell is perpetually associated with 1984; in July 1984, an asteroid was discovered by Antonín Mrkos and named after Orwell.

- In 1955, an episode of BBC's The Goon Show, 1985, was broadcast, written by Spike Milligan and Eric Sykes and based on Nigel Kneale's television adaptation. It was re-recorded about a month later with the same script but a slightly different cast. 1985 parodies many of the main scenes in Orwell's novel.

- In 1970, the American rock group Spirit released the song "1984" based on Orwell's novel.

- In 1973, ex-Soft Machine bassist Hugh Hopper released an album called 1984 on the Columbia label (UK), consisting of instrumentals with Orwellian titles such as “Miniluv,” “Minipax,” “Minitrue,” and so forth.

- In 1974, David Bowie released the album Diamond Dogs, which is thought to be loosely based on the novel Nineteen Eighty-Four. It includes the tracks "We Are The Dead", "1984" and "Big Brother". Before the album was made, Bowie's management (MainMan) had planned for Bowie and Tony Ingrassia (MainMan's creative consultant) to co-write and direct a musical production of Orwell's Nineteen Eighty-Four, but Orwell's widow refused to give MainMan the rights.

- In 1977, the British rock band The Jam released the album This Is the Modern World, which includes the track "Standards" by Paul Weller. This track concludes with the lyrics "...and ignorance is strength, we have God on our side, look, you know what happened to Winston."

- In 1984, Ridley Scott directed a television commercial, "1984", to launch Apple's Macintosh computer. The advert stated, "1984 won't be like 1984", suggesting that the Apple Mac would be freedom from Big Brother; i.e., the IBM PC.

- An episode of Doctor Who, called "The God Complex", depicts an alien ship disguised as a hotel containing Room 101-like spaces, and quotes the nursery rhyme as well.

- The two part episode Chain of Command on Star Trek: The Next Generation bears some resemblances to the novel.

- Radiohead’s 2003 single “2 + 2 = 5”, from their album Hail to the Thief, is Orwellian by title and content. Thom Yorke states, “I was listening to a lot of political programs on BBC Radio 4. I found myself writing down little nonsense phrases, those Orwellian euphemisms that [the British and American governments] are so fond of. They became the background of the record.”

- In September 2009, the English progressive rock band Muse released The Resistance, which included songs influenced by Nineteen Eighty-Four.

- In Marilyn Manson’s autobiography The Long Hard Road Out of Hell, he states: "I was thoroughly terrified by the idea of the end of the world and the Antichrist. So I became obsessed with it... reading prophetic books like... 1984 by George Orwell..."

- In 2012, the film Cloud Atlas depicts a dark, dystopian future where a global world government is in power. A captured political prisoner is interrogated by a government official and warned not to use Korean, referred to as subspeak. Similarly in the book, English is no longer in use having been diluted into Newspeak, an ideological language designed to support the party line, curtailing illegal thoughts and even preventing their formation.

References to the themes, concepts and plot of Nineteen Eighty-Four have appeared frequently in other works, especially in popular music and video entertainment. An example is the worldwide hit reality television show Big Brother, in which a group of people live together in a large house, isolated from the outside world but continuously watched by television cameras.

- In November 2011, the US government argued before the US Supreme Court that it wants to continue utilising GPS tracking of individuals without first seeking a warrant. In response, Justice Stephen Breyer questioned what that means for a democratic society by referencing Nineteen Eighty-Four. Justice Breyer asked, "If you win this case, then there is nothing to prevent the police or the government from monitoring 24 hours a day the public movement of every citizen of the United States. So if you win, you suddenly produce what sounds like Nineteen Eighty-Four... "

The book touches on the invasion of privacy and ubiquitous surveillance. From mid-2013 it was publicised that the NSA has been secretly monitoring and storing global internet traffic, including the bulk data collection of email and phone call data. Sales of Nineteen Eighty-Four increased by up to seven times within the first week of the 2013 mass surveillance leaks. The book again topped the Amazon.com sales charts in 2017 after a controversy involving Kellyanne Conway using the phrase "alternative facts" to explain discrepancies with the media.

The book also shows mass media as a catalyst for the intensification of destructive emotions and violence. Since the 20th century, news and other forms of media have been publicising violence more often. In 2013, Nottingham Playhouse, the Almeida Theatre and Headlong staged a successful new adaptation (by Robert Icke and Duncan Macmillan), which twice toured the UK and played an extended run in London's West End. The play opened on Broadway in New York in 2017. A version of the production played on an Australian tour in 2017.

Nineteen Eighty-Four was number three on the list of "Top Check Outs Of All Time" by the New York Public Library.

In accordance with copyright law, Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm both entered the public domain on January 1, 2021 in most of the world, 70 calendar years after Orwell died. The US copyright expiration is different for both novels: 95 years after publication.

Brave New World comparisons

In October 1949, after reading Nineteen Eighty-Four, Huxley sent a letter to Orwell in which he argued that it would be more efficient for rulers to stay in power by the softer touch by allowing citizens to seek pleasure to control them rather than use brute force. He wrote,

Whether in actual fact the policy of the boot-on-the-face can go on indefinitely seems doubtful. My own belief is that the ruling oligarchy will find less arduous and wasteful ways of governing and of satisfying its lust for power, and these ways will resemble those which I described in Brave New World.

...

Within the next generation I believe that the world's rulers will discover that infant conditioning and narco-hypnosis are more efficient, as instruments of government, than clubs and prisons, and that the lust for power can be just as completely satisfied by suggesting people into loving their servitude as by flogging and kicking them into obedience.

In the decades since the publication of Nineteen Eighty-Four, there have been numerous comparisons to Huxley's Brave New World, which had been published 17 years earlier, in 1932. They are both predictions of societies dominated by a central government and are both based on extensions of the trends of their times. However, members of the ruling class of Nineteen Eighty-Four use brutal force, torture and mind control to keep individuals in line, while rulers in Brave New World keep the citizens in line by addictive drugs and pleasurable distractions. Regarding censorship, in Nineteen Eighty-Four the government tightly controls information to keep the population in line, but in Huxley's world, so much information is published that readers do not know which information is relevant, and what can be disregarded.

Elements of both novels can be seen in modern-day societies, with Huxley's vision being more dominant in the West and Orwell's vision more prevalent with dictatorships, including those in communist countries (such as in modern-day China and North Korea), as is pointed out in essays that compare the two novels, including Huxley's own Brave New World Revisited.

Comparisons with other dystopian novels like The Handmaid's Tale, Virtual Light, The Private Eye and The Children of Men have also been drawn.