| Mexican–American War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

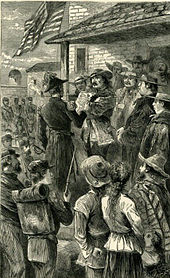

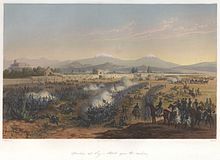

Clockwise from top Battle of Resaca de la Palma, U.S. victory at Churubusco outside of Mexico City, marines storming Chapultepec castle under a large U.S. flag, Battle of Cerro Gordo | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| 73,532 | 82,000 | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| 4,000 civilians killed | |||||||||

| Including civilians killed by violence, military deaths from disease and accidental deaths, the Mexican death toll may have reached 25,000 and the American death toll exceeded 13,283. | |||||||||

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the Intervención estadounidense en México (U.S. intervention in Mexico), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1845 U.S. annexation of Texas, which Mexico considered Mexican territory since the Mexican government did not recognize the Velasco treaty signed by Mexican General Antonio López de Santa Anna when he was a prisoner of the Texian Army during the 1836 Texas Revolution. The Republic of Texas was de facto an independent country, but most of its citizens wished to be annexed by the United States. Domestic sectional politics in the U.S. were preventing annexation since Texas would have been a slave state, upsetting the balance of power between Northern free states and Southern slave states. In the 1844 United States presidential election, Democrat James K. Polk was elected on a platform of expanding U.S. territory in Oregon and Texas. Polk advocated expansion by either peaceful means or armed force, with the 1845 annexation of Texas furthering that goal by peaceful means. However, the boundary between Texas and Mexico was disputed, with the Republic of Texas and the U.S. asserting it to be the Rio Grande River and Mexico claiming it to be the more-northern Nueces River. Both Mexico and the U.S. claimed the disputed area and sent troops. Polk sent U.S. Army troops to the area; he also sent a diplomatic mission to Mexico to try to negotiate the sale of territory. U.S. troops' presence was designed to lure Mexico into starting the conflict, putting the onus on Mexico and allowing Polk to argue to Congress that a declaration of war should be issued. Mexican forces attacked U.S. forces, and the United States Congress declared war.

Beyond the disputed area of Texas, U.S. forces quickly occupied the regional capital of Santa Fe de Nuevo México along the upper Rio Grande, which had trade relations with the U.S. via the Santa Fe Trail between Missouri and New Mexico. U.S. forces also moved against the province of Alta California and then moved south. The Pacific Squadron of the U.S. Navy blockaded the Pacific coast farther south in the lower Baja California Territory. The Mexican government refused to be pressured into signing a peace treaty at this point, making the U.S. invasion of the Mexican heartland under Major General Winfield Scott and its capture of the capital Mexico City a strategy to force peace negotiations. Although Mexico was defeated on the battlefield, politically its government's negotiating a treaty remained a fraught issue, with some factions refusing to consider any recognition of its loss of territory. Although Polk formally relieved his peace envoy, Nicholas Trist, of his post as negotiator, Trist ignored the order and successfully concluded the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. It ended the war, and Mexico recognized the Mexican Cession, areas not part of disputed Texas but conquered by the U.S. Army. These were northern territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México. The U.S. agreed to pay $15 million for the physical damage of the war and assumed $3.25 million of debt already owed by the Mexican government to U.S. citizens. Mexico acknowledged the independence of what became the State of Texas and accepted the Rio Grande as its northern border with the United States.

The victory and territorial expansion Polk envisioned inspired patriotism among some sections of the United States, but the war and treaty drew fierce criticism for the casualties, monetary cost, and heavy-handedness, particularly early on. The question of how to treat the new acquisitions also intensified the debate over slavery in the United States. Although the Wilmot Proviso that explicitly forbade the extension of slavery into conquered Mexican territory was not adopted by Congress, debates about it heightened sectional tensions. Some scholars see the Mexican–American War as leading to the American Civil War, with many officers trained at West Point, who saw action in Mexico, playing prominent leadership roles on each side during the conflict.

In Mexico, the war worsened domestic political turmoil. Since the war was fought on home ground, Mexico suffered a large loss of life of both its soldiers and its civilian population. The nation's financial foundations were undermined, territory was lost, and national prestige left it in what a group of Mexican writers including Ramón Alcaraz and José María del Castillo Velasco called a "state of degradation and ruin...” This group did not acknowledge Mexico’s refusal to admit the independence of Texas as a cause of the war, instead proclaiming “[As for] the true origin of the war, it is sufficient to say that the insatiable ambition of the United States, favored by our weakness, caused it."

Background

Mexico after independence

Mexico obtained independence from the Spanish Empire with the Treaty of Córdoba in 1821 after a decade of conflict between the royal army and insurgents for independence, with no foreign intervention. The conflict ruined the silver-mining districts of Zacatecas and Guanajuato, so that Mexico began as a sovereign nation with its future financial stability from its main export destroyed. Mexico briefly experimented with monarchy, but became a republic in 1824. This government was characterized by instability, leaving it ill-prepared for a major international conflict when war broke out with the U.S. in 1846. Mexico had successfully resisted Spanish attempts to reconquer its former colony in the 1820s and resisted the French in the so-called Pastry War of 1838, but the secessionists' success in Texas and the Yucatan against the centralist government of Mexico showed the weakness of the Mexican government, which changed hands multiple times. The Mexican military and the Catholic Church in Mexico, both privileged institutions with conservative political views, were stronger politically than the Mexican state.

U.S. expansionism

Since the early 19th century, the U.S. sought to expand its territory. Jefferson's Louisiana Purchase from France in 1803 gave Spain and the U.S. an undefined border. The young and weak U.S. fought the War of 1812 with Britain, with the U.S. launching an unsuccessful invasion of British Canada and Britain launching an equally unsuccessful counter-invasion. Some boundary issues were solved between the U.S. and Spain with the Adams-Onis Treaty of 1818. U.S. negotiator John Quincy Adams wanted clear possession of East Florida and establishment of U.S. claims above the 42nd parallel, while Spain sought to limit U.S. expansion into what is now the American Southwest. The U.S. then sought to purchase territory from Mexico, starting in 1825. U.S. President Andrew Jackson made a sustained effort to acquire northern Mexican territory, with no success.

Historian Peter Guardino states that in the war "the greatest advantage the United States had was its prosperity." Economic prosperity contributed to political stability in the U.S. Unlike Mexico's financial precariousness, the U.S. was a prosperous country with major resource endowments that Mexico lacked. Its war of independence had taken place generations earlier and was a relatively short conflict that ended with French intervention on the side of the 13 colonies. After independence, the U.S. grew rapidly and expanded westward, marginalizing and displacing Native Americans as settlers cleared land and established farms. With the Industrial Revolution across the Atlantic increasing the demand for cotton for textile factories, there was a large external market of a valuable commodity produced by slave labor in the southern states. This demand helped fuel expansion into northern Mexico. Although there were political conflicts in the U.S., they were largely contained by the framework of the constitution and did not result in revolution or rebellion by 1846, but rather by sectional political conflicts. The expansionism of the U.S. was driven in part by the need to acquire new territory for economic reasons, in particular, as cotton exhausted the soil in areas of the south, new lands had to be brought under cultivation to supply the demand for it. Northerners in the U.S. sought to develop the country's existing resources and expand the industrial sector without expanding the nation's territory. The existing balance of sectional interests would be disrupted by the expansion of slavery into new territory. The Democratic Party strongly supported expansion, so it is not by chance that the U.S. went to war with Mexico under Democratic President James K. Polk.

Instability in northern Mexico

Neither colonial Mexico nor the newly sovereign Mexican state effectively controlled Mexico's far north and west. Mexico's military and diplomatic capabilities declined after it attained independence from Spain in 1821 and left the northern one-half of the country vulnerable to attacks by Comanche, Apache, and Navajo Native Americans. The Comanche, in particular, took advantage of the weakness of the Mexican state to undertake large-scale raids hundreds of miles into the country to acquire livestock for their own use and to supply an expanding market in Texas and the U.S.

The northern area of Mexico was sparsely settled because of its climate and topography. It was mainly desert with little rainfall so that sedentary agriculture never developed there during the pre-Hispanic or colonial periods. During the colonial era (1521–1821) it had not been well controlled politically. After independence, Mexico contended with internal struggles that sometimes verged on civil war, and the situation on the northern frontier was not a high priority for the government in central Mexico. In northern Mexico, the end of Spanish rule was marked by the end of financing for presidios and for gifts to Native Americans to maintain the peace. The Comanche and Apache were successful in raiding for livestock and looting much of northern Mexico outside the scattered cities. The raids after 1821 resulted in the death of many Mexicans, halted most transportation and communications, and decimated the ranching industry that was a mainstay of the northern economy. As a result, the demoralized civilian population of northern Mexico put up little resistance to the invading U.S. army.

Distance and hostile activity from Native Americans also made communications and trade between the heartland of Mexico and provinces such as Alta California and New Mexico difficult. As a result, New Mexico was dependent on the overland Santa Fe Trail trade with the United States at the outbreak of the war.

The Mexican government's policy of settlement of U.S. citizens in its province of Tejas was aimed at expanding control into Comanche lands, the Comancheria. But, instead of settling in the dangerous central and western parts of the province, people settled in East Texas, which held rich farmland contiguous to the southern U.S. slave states. As settlers poured in from the U.S., the Mexican government discouraged further settlement with its 1829 abolition of slavery.

Foreign designs on California

During the Spanish colonial era, the Californias (i.e., the Baja California peninsula and Alta California) were sparsely settled. After Mexico became independent, it shut down the missions and reduced its military presence. In 1842, the U.S. minister in Mexico, Waddy Thompson Jr., suggested Mexico might be willing to cede Alta California to the U.S. to settle debts, saying: "As to Texas, I regard it as of very little value compared with California, the richest, the most beautiful, and the healthiest country in the world ... with the acquisition of Upper California we should have the same ascendency on the Pacific ... France and England both have had their eyes upon it."

U.S. President John Tyler's administration suggested a tripartite pact to settle the Oregon boundary dispute and provide for the cession of the port of San Francisco from Mexico. Lord Aberdeen declined to participate but said Britain had no objection to U.S. territorial acquisition there. The British minister in Mexico, Richard Pakenham, wrote in 1841 to Lord Palmerston urging "to establish an English population in the magnificent Territory of Upper California", saying that "no part of the World offering greater natural advantages for the establishment of an English colony ... by all means desirable ... that California, once ceasing to belong to Mexico, should not fall into the hands of any power but England ... there is some reason to believe that daring and adventurous speculators in the United States have already turned their thoughts in this direction." By the time the letter reached London, though, Sir Robert Peel's Tory government, with its Little England policy, had come to power and rejected the proposal as expensive and a potential source of conflict.

A significant number of influential Californios supported annexation, either by the United States or by the United Kingdom. Pío de Jesús Pico IV, the last governor of Alta California, supported British annexation.

Texas revolution, republic, and U.S. annexation

In 1800, Spain's colonial province of Texas (Tejas) had few inhabitants, with only about 7,000 non-Indian settlers. The Spanish crown developed a policy of colonization to more effectively control the territory. After independence, the Mexican government implemented the policy, granting Moses Austin, a banker from Missouri, a large tract of land in Texas. Austin died before he could bring his plan of recruiting American settlers for the land to fruition, but his son, Stephen F. Austin, brought over 300 American families into Texas. This started the steady trend of migration from the United States into the Texas frontier. Austin's colony was the most successful of several colonies authorized by the Mexican government. The Mexican government intended the new settlers to act as a buffer between the Tejano residents and the Comanches, but the non-Hispanic colonists tended to settle in areas with decent farmland and trade connections with Louisiana rather than farther west where they would have been an effective buffer against the Indians.

In 1829, because of the large influx of American immigrants, the non-Hispanic outnumbered native Spanish speakers in Texas. President Vicente Guerrero, a hero of Mexican independence, moved to gain more control over Texas and its influx of non-Hispanic colonists from the southern U.S. and discourage further immigration by abolishing slavery in Mexico. The Mexican government also decided to reinstate the property tax and increase tariffs on shipped American goods. The settlers and many Mexican businessmen in the region rejected the demands, which led to Mexico closing Texas to additional immigration, which continued from the United States into Texas illegally.

In 1834, Mexican conservatives seized the political initiative, and General Antonio López de Santa Anna became the centralist president of Mexico. The conservative-dominated Congress abandoned the federal system, replacing it with a unitary central government that removed power from the states. Leaving politics to those in Mexico City, General Santa Anna led the Mexican army to quash the semi-independence of Texas. He had done that in Coahuila (in 1824, Mexico had merged Texas and Coahuila into the enormous state of Coahuila y Tejas). Austin called Texians to arms and they declared independence from Mexico in 1836. After Santa Anna defeated the Texians in the Battle of the Alamo, he was defeated by the Texian Army commanded by General Sam Houston and was captured at the Battle of San Jacinto; he signed a treaty with Texas President David Burnet to allow Texas to plead its case for independence with the Mexican government but did not commit himself or Mexico to anything beyond that. He negotiated under duress and as a captive, and therefore had no standing to commit Mexico to a treaty. The Mexican Congress did not ratify it. Although Mexico did not recognize Texas independence, Texas consolidated its status as an independent republic and received official recognition from Britain, France, and the United States, which all advised Mexico not to try to reconquer the new nation. Most Texians wanted to join the United States, but the annexation of Texas was contentious in the U.S. Congress, where Whigs and Abolitionists were largely opposed, although neither group went so far as to deny funds for the war. In 1845, Texas agreed to the offer of annexation by the U.S. Congress and became the 28th state on December 29, 1845, which set the stage for the conflict with Mexico.

Prelude

Nueces Strip

By the Treaties of Velasco made after Texans captured General Santa Ana after the Battle of San Jacinto, the southern border of Texas was placed at the "Rio Grande del Norte." The Texans claimed this placed the southern border at the modern Rio Grande. The Mexican government disputed this placement on two grounds: first, it rejected the idea of Texas independence; and second, it claimed that the Rio Grande in the treaty was actually the Nueces River, since the current Rio Grande has always been called "Rio Bravo" in Mexico. The latter claim belied the full name of the river in Mexico, however: "Rio Bravo del Norte." The ill-fated Texan Santa Fe Expedition of 1841 attempted to realize the claim to New Mexican territory east of the Rio Grande, but its members were captured by the Mexican Army and imprisoned. Reference to the Rio Grande boundary of Texas was omitted from the U.S. Congress's annexation resolution to help secure passage after the annexation treaty failed in the Senate. President Polk claimed the Rio Grande boundary, and when Mexico sent forces over the Rio Grande, this provoked a dispute.

Polk's gambits

In July 1845, Polk sent General Zachary Taylor to Texas, and by October, Taylor commanded 3,500 Americans on the Nueces River, ready to take by force the disputed land. Polk wanted to protect the border and also coveted for the U.S. the continent clear to the Pacific Ocean. At the same time, Polk wrote to the American consul in the Mexican territory of Alta California, disclaiming American ambitions in California but offering to support independence from Mexico or voluntary accession to the United States, and warning that the United States would oppose any European attempts to take over.

To end another war scare with the United Kingdom over the Oregon Country, Polk signed the Oregon Treaty dividing the territory, angering Northern Democrats who felt he was prioritizing Southern expansion over Northern expansion.

In the winter of 1845–46, the federally commissioned explorer John C. Frémont and a group of armed men appeared in Alta California. After telling the Mexican governor and the American Consul Larkin he was merely buying supplies on the way to Oregon, he instead went to the populated area of California and visited Santa Cruz and the Salinas Valley, explaining he had been looking for a seaside home for his mother. Mexican authorities became alarmed and ordered him to leave. Frémont responded by building a fort on Gavilan Peak and raising the American flag. Larkin sent word that Frémont's actions were counterproductive. Frémont left California in March but returned to California and took control of the California Battalion following the outbreak of the Bear Flag Revolt in Sonoma.

In November 1845, Polk sent John Slidell, a secret representative, to Mexico City with an offer to the Mexican government of $25 million for the Rio Grande border in Texas and Mexico's provinces of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México. U.S. expansionists wanted California to thwart any British interests in the area and to gain a port on the Pacific Ocean. Polk authorized Slidell to forgive the $3 million owed to U.S. citizens for damages caused by the Mexican War of Independence and pay another $25 to $30 million for the two territories.

Mexico's response

Mexico was neither inclined nor able to negotiate. In 1846 alone, the presidency changed hands four times, the war ministry six times, and the finance ministry sixteen times. Despite that, Mexican public opinion and all political factions agreed that selling the territories to the United States would tarnish the national honor. Mexicans who opposed direct conflict with the United States, including President José Joaquín de Herrera, were viewed as traitors. Military opponents of de Herrera, supported by populist newspapers, considered Slidell's presence in Mexico City an insult. When de Herrera considered receiving Slidell to settle the problem of Texas annexation peacefully, he was accused of treason and deposed. After a more nationalistic government under General Mariano Paredes y Arrillaga came to power, it publicly reaffirmed Mexico's claim to Texas; Slidell, convinced that Mexico should be "chastised", returned to the U.S.

Preparation for war

Challenges in Mexico

Mexican Army

The Mexican Army emerged from the war of independence as a weak and divided force. Only 7 of the 19 states that formed the Mexican federation sent soldiers, armament, and money for the war effort, as the young Republic had not yet developed a sense of a unifying, national identity. Mexican soldiers were not easily melded into an effective fighting force. Santa Anna said, "the leaders of the army did their best to train the rough men who volunteered, but they could do little to inspire them with patriotism for the glorious country they were honored to serve." According to the leading Mexican conservative politician, Lucas Alamán, the "money spent on arming Mexican troops merely enabled them to fight each other and 'give the illusion' that the country possessed an army for its defense." However, an officer criticized Santa Anna's training of troops, "The cavalry was drilled only in regiments. The artillery hardly ever maneuvered and never fired a blank shot. The general in command was never present on the field of maneuvers, so that he was unable to appreciate the respective qualities of the various bodies under his command ... If any meetings of the principal commanding officers were held to discuss the operations of the campaign, it was not known, nor was it known whether any plan of campaign had been formed."

At the beginning of the war, Mexican forces were divided between the permanent forces (permanentes) and the active militiamen (activos). The permanent forces consisted of 12 regiments of infantry (of two battalions each), three brigades of artillery, eight regiments of cavalry, one separate squadron and a brigade of dragoons. The militia amounted to nine infantry and six cavalry regiments. In the northern territories, presidial companies (presidiales) protected the scattered settlements. Since Mexico fought the war on its home territory, a traditional support system for troops were women, known as soldaderas. They did not participate in conventional fighting on battlefields, but some soldaderas joined the battle alongside the men. These women were involved in fighting during the defense of Mexico City and Monterey. Some women such as Dos Amandes and María Josefa Zozaya would be remembered as heroes.

The Mexican army was using surplus British muskets (such as the Brown Bess), left over from the Napoleonic Wars. While at the beginning of the war most American soldiers were still equipped with the very similar Springfield 1816 flintlock muskets, more reliable caplock models gained large inroads within the rank and file as the conflict progressed. Some U.S. troops carried radically modern weapons that gave them a significant advantage over their Mexican counterparts, such as the Springfield 1841 rifle of the Mississippi Rifles and the Colt Paterson revolver of the Texas Rangers. In the later stages of the war, the U.S. Mounted Rifles were issued Colt Walker revolvers, of which the U.S. Army had ordered 1,000 in 1846. Most significantly, throughout the war, the superiority of the U.S. artillery often carried the day. While technologically Mexican and American artillery operated on the same plane, U.S. army training, as well as the quality and reliability of their logistics, gave U.S. guns and cannoneers a significant edge.

In his 1885 memoirs, former U.S. President Ulysses Grant (himself a veteran of the Mexican war) attributed Mexico's defeat to the poor quality of their army, writing:

"The Mexican army of that day was hardly an organization. The private soldier was picked from the lower class of the inhabitants when wanted; his consent was not asked; he was poorly clothed, worse fed, and seldom paid. He was turned adrift when no longer wanted. The officers of the lower grades were but little superior to the men. With all this I have seen as brave stands made by some of these men as I have ever seen made by soldiers. Now Mexico has a standing army larger than the United States. They have a military school modeled after West Point. Their officers are educated and, no doubt, very brave. The Mexican war of 1846–8 would be an impossibility in this generation."

Political divisions

There were significant political divisions in Mexico, but Mexicans were united in their opposition to the foreign aggression and stood for Mexico. Political differences seriously impeded Mexicans in the conduct of the war, but there was no disunity on their national stance. Inside Mexico, the conservative centralistas and liberal federalists vied for power, and at times these two factions inside Mexico's military fought each other rather than the invading U.S. Army. Santa Anna bitterly remarked, "However shameful it may be to admit this, we have brought this disgraceful tragedy upon ourselves through our interminable in-fighting."

During the conflict, presidents held office for a period of months, sometimes just weeks, or even days. Just before the outbreak of the war, liberal General José Joaquín de Herrera was president (December 1844 – December 1845) and willing to engage in talks so long as he did not appear to be caving to the U.S., but he was accused by many Mexican factions of selling out his country (vendepatria) for considering it. He was overthrown by Conservative Mariano Paredes (December 1845 – July 1846), who left the presidency to fight the invading U.S. Army and was replaced by his vice president Nicolás Bravo (July 28, 1846 – August 4, 1846). The conservative Bravo was overthrown by federalist liberals who re-established the federal Constitution of 1824. José Mariano Salas (August 6, 1846 – December 23, 1846) served as president and held elections under the restored federalist system. General Antonio López de Santa Anna won those elections, but as was his practice, he left the administration to his vice president, who was again liberal Valentín Gómez Farías (December 23, 1846 – March 21, 1847). In February 1847, conservatives rebelled against the liberal government's attempt to take Church property to fund the war effort. In the Revolt of the Polkos, the Catholic Church and conservatives paid soldiers to rise against the liberal government. Santa Anna had to leave his campaign to return to the capital to sort out the political mess.

Santa Anna briefly held the presidency again, from March 21, 1847 – April 2, 1847. His troops were deprived of support that would allow them to continue the fight. The conservatives demanded the removal of Gómez Farías, and this was accomplished by abolishing the office of vice president. Santa Anna returned to the field, replaced in the presidency by Pedro María de Anaya (April 2, 1847 – May 20, 1847). Santa Anna returned to the presidency on May 20, 1847, when Anaya left to fight the invasion, serving until September 15, 1847. Preferring the battlefield to administration, Santa Anna left office again, leaving the office to Manuel de la Peña y Peña (September 16, 1847 – November 13, 1847).

With U.S. forces occupying the Mexican capital and much of the heartland, negotiating a peace treaty was an exigent matter, and Peña y Peña left office to do that. Pedro María Anaya returned to the presidency on November 13, 1847 – January 8, 1848. Anaya refused to sign any treaty that ceded land to the U.S., despite the situation on the ground with Americans occupying the capital, Peña y Peña resumed the presidency January 8, 1848 – June 3, 1848, during which time the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed, bringing the war to an end.

Challenges in the United States

United States Army

Polk had pledged to seek expanded territory in Oregon and Texas, as part of his campaign in 1844, but the regular army was not sufficiently large to sustain extended conflicts on two fronts. The Oregon dispute with Britain was settled peaceably by treaty, allowing U.S. forces to concentrate on the southern border.

The war was fought by regiments of regulars and various regiments, battalions, and companies of volunteers from the different states of the Union as well as Americans and some Mexicans in California and New Mexico. On the West Coast, the U.S. Navy fielded a battalion of sailors, in an attempt to recapture Los Angeles. Although the U.S. Army and Navy were not large at the outbreak of the war, the officers were generally well trained and the numbers of enlisted men fairly large compared to Mexico's. At the beginning of the war, the U.S. Army had eight regiments of infantry (three battalions each), four artillery regiments and three mounted regiments (two dragoons, one of mounted rifles). These regiments were supplemented by 10 new regiments (nine of infantry and one of cavalry) raised for one year of service by the act of Congress from February 11, 1847. A large portion of this fighting force consisted of recent immigrants. According to Tyler V. Johnson, foreign-born men amounted to 47 percent of General Taylor's total forces. In addition to a large contingent of Irish- and German-born soldiers, nearly all European states and principalities were represented. It is estimated that the U.S. Army further included 1,500 men from British North America, including French Canadians.

Although Polk hoped to avoid a protracted war over Texas, the extended conflict stretched regular army resources, necessitating the recruitment of volunteers with short-term enlistments. Some enlistments were for a year, but others were for 3 or 6 months. The best volunteers signed up for a year's service in the summer of 1846, with their enlistments expiring just when General Winfield Scott's campaign was poised to capture Mexico City. Many did not re-enlist, deciding that they would rather return home than place themselves in harm's way of disease, threat of death or injury on the battlefield, or in guerrilla warfare. Their patriotism was doubted by some in the U.S., but they were not counted as deserters. The volunteers were far less disciplined than the regular army, with many committing attacks on the civilian population, sometimes stemming from anti-Catholic and anti-Mexican racial bias. Soldiers' memoirs describe cases of looting and murder of Mexican civilians, mostly by volunteers. One officer's diary records: "We reached Burrita about 5 pm, many of the Louisiana volunteers were there, a lawless drunken rabble. They had driven away the inhabitants, taken possession of their houses, and were emulating each other in making beasts of themselves." John L. O'Sullivan, a vocal proponent of Manifest Destiny, later recalled "The regulars regarded the volunteers with importance and contempt ... [The volunteers] robbed Mexicans of their cattle and corn, stole their fences for firewood, got drunk, and killed several inoffensive inhabitants of the town in the streets." Many of the volunteers were unwanted and considered poor soldiers. The expression "Just like Gaines's army" came to refer to something useless, the phrase having originated when a group of untrained and unwilling Louisiana troops was rejected and sent back by General Taylor at the beginning of the war.

In his 1885 memoirs, Ulysses Grant assesses the U.S. armed forces facing Mexico more favorably.

The victories in Mexico were, in every instance, over vastly superior numbers. There were two reasons for this. Both General Scott and General Taylor had such armies as are not often got together. At the battles of Palo Alto and Resaca-de-la-Palma, General Taylor had a small army, but it was composed exclusively of regular troops, under the best of drill and discipline. Every officer, from the highest to the lowest, was educated in his profession, not at West Point necessarily, but in the camp, in garrison, and many of them in Indian wars. The rank and file were probably inferior, as material out of which to make an army, to the volunteers that participated in all the later battles of the war; but they were brave men, and then drill and discipline brought out all there was in them. A better army, man for man, probably never faced an enemy than the one commanded by General Taylor in the earliest two engagements of the Mexican war. The volunteers who followed were of better material, but without drill or discipline at the start. They were associated with so many disciplined men and professionally educated officers, that when they went into engagements it was with a confidence they would not have felt otherwise. They became soldiers themselves almost at once. All these conditions we would enjoy again in case of war.

Political divisions

The U.S. had been an independent country since the American Revolution, and it was a strongly divided country along sectional lines. Enlarging the country, particularly through armed combat against a sovereign nation, deepened sectional divisions. Polk had narrowly won the popular vote in the 1844 presidential election and decisively won the Electoral College, but with the annexation of Texas in 1845 and the outbreak of war in 1846, Polk's Democrats lost the House of Representatives to the Whig Party, which opposed the war. Unlike Mexico, which had weak formal institutions of governance, frequent changes in government, and a military that regularly intervened in politics, the U.S. generally kept its political divisions within the bounds of the institutions of governance.

Outbreak of hostilities

Texas Campaign

Thornton Affair

President Polk ordered General Taylor and his forces south to the Rio Grande. Taylor ignored Mexican demands to withdraw to the Nueces. He constructed a makeshift fort (later known as Fort Brown/Fort Texas) on the banks of the Rio Grande opposite the city of Matamoros, Tamaulipas.

The Mexican forces prepared for war. On April 25, 1846, a 2,000-man Mexican cavalry detachment attacked a 70-man U.S. patrol commanded by Captain Seth Thornton, which had been sent into the contested territory north of the Rio Grande and south of the Nueces River. In the Thornton Affair, the Mexican cavalry routed the patrol, killing 11 American soldiers and capturing 52.

Siege of Fort Texas

A few days after the Thornton Affair, the Siege of Fort Texas began on May 3, 1846. Mexican artillery at Matamoros opened fire on Fort Texas, which replied with its own guns. The bombardment continued for 160 hours and expanded as Mexican forces gradually surrounded the fort. Thirteen U.S. soldiers were injured during the bombardment, and two were killed. Among the dead was Jacob Brown, after whom the fort was later named.

Battle of Palo Alto

On May 8, 1846, Zachary Taylor and 2,400 troops arrived to relieve the fort. However, General Arista rushed north with a force of 3,400 and intercepted him about 5 miles (8 km) north of the Rio Grande River, near modern-day Brownsville, Texas. The U.S. Army employed "flying artillery", their term for horse artillery, a mobile light artillery mounted on horse carriages with the entire crew riding horses into battle. The fast-firing artillery and highly mobile fire support had a devastating effect on the Mexican army. In contrast to the "flying artillery" of the Americans, the Mexican cannons at the Battle of Palo Alto had lower-quality gunpowder that fired at velocities slow enough to make it possible for American soldiers to dodge artillery rounds. The Mexicans replied with cavalry skirmishes and their own artillery. The U.S. flying artillery somewhat demoralized the Mexican side, and seeking terrain more to their advantage, the Mexicans retreated to the far side of a dry riverbed (resaca) during the night and prepared for the next battle. It provided a natural fortification, but during the retreat, Mexican troops were scattered, making communication difficult.

Battle of Resaca de la Palma

During the Battle of Resaca de la Palma on May 9, 1846, the two sides engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat. The U.S. Cavalry managed to capture the Mexican artillery, causing the Mexican side to retreat—a retreat that turned into a rout. Fighting on unfamiliar terrain, his troops fleeing in retreat, Arista found it impossible to rally his forces. Mexican casualties were significant, and the Mexicans were forced to abandon their artillery and baggage. Fort Brown inflicted additional casualties as the withdrawing troops passed by the fort, and additional Mexican soldiers drowned trying to swim across the Rio Grande. Taylor crossed the Rio Grande and began his series of battles in Mexican territory.

Declarations of war, May 1846

Polk received word of the Thornton Affair, which, added to the Mexican government's rejection of Slidell, Polk believed, constituted a casus belli. His message to Congress on May 11, 1846, claimed that "Mexico has passed the boundary of the United States, has invaded our territory and shed American blood upon American soil."

The U.S. Congress approved the declaration of war on May 13, 1846, after a few hours of debate, with southern Democrats in strong support. Sixty-seven Whigs voted against the war on a key slavery amendment, but on the final passage only 14 Whigs voted no, including Rep. John Quincy Adams. Later, a freshman Whig Congressman from Illinois, Abraham Lincoln, challenged Polk's assertion that American blood had been shed on American soil, calling it "a bold falsification of history."

Regarding the beginning of the war, Ulysses S. Grant, who had opposed the war but served as an army lieutenant in Taylor's Army, claims in his Personal Memoirs (1885) that the main goal of the U.S. Army's advance from Nueces River to the Rio Grande was to provoke the outbreak of war without attacking first, to debilitate any political opposition to the war.

The presence of United States troops on the edge of the disputed territory farthest from the Mexican settlements, was not sufficient to provoke hostilities. We were sent to provoke a fight, but it was essential that Mexico should commence it. It was very doubtful whether Congress would declare war; but if Mexico should attack our troops, the Executive could announce, "Whereas, war exists by the acts of, etc.," and prosecute the contest with vigor. Once initiated there were, but few public men who would have the courage to oppose it. ... Mexico showing no willingness to come to the Nueces to drive the invaders from her soil, it became necessary for the "invaders" to approach to within a convenient distance to be struck. Accordingly, preparations were begun for moving the army to the Rio Grande, to a point near Matamoras [sic]. It was desirable to occupy a position near the largest centre of population possible to reach, without absolutely invading territory to which we set up no claim whatever.

In Mexico, although President Paredes issued a manifesto on May 23, 1846, and a declaration of a defensive war on April 23, both of which are considered by some the de facto start of the war, Mexico officially declared war by Congress on July 7, 1846.

General Santa Anna's return

Mexico's defeats at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma set the stage for the return of Santa Anna, who at the outbreak of the war, was in exile in Cuba. He wrote to the government in Mexico City, stating he did not want to return to the presidency, but he would like to come out of exile in Cuba to use his military experience to reclaim Texas for Mexico. President Farías was driven to desperation. He accepted the offer and allowed Santa Anna to return. Unbeknownst to Farías, Santa Anna had secretly been dealing with U.S. representatives to discuss a sale of all contested territory to the U.S. at a reasonable price, on the condition that he be allowed back in Mexico through the U.S. naval blockades. Polk sent his own representative to Cuba, Alexander Slidell MacKenzie, to negotiate directly with Santa Anna. The negotiations were secret and there are no written records of the meetings, but there was some understanding that came out of the meetings. Polk asked Congress for $2 million to be used in negotiating a treaty with Mexico. The U.S. allowed Santa Anna to return to Mexico, lifting the Gulf Coast naval blockade. However, in Mexico, Santa Anna denied all knowledge of meeting with the U.S. representative or any offers or transactions. Rather than being Polk's ally, he pocketed any money given him and began to plan the defense of Mexico. The Americans were dismayed, including General Scott, as this was an unexpected result. "Santa Anna gloated over his enemies' naïveté: 'The United States was deceived in believing that I would be capable of betraying my mother country.'" Santa Anna avoided getting involved in politics, dedicating himself to Mexico's military defense. While politicians attempted to reset the governing framework to a federal republic, Santa Anna left for the front to retake lost northern territory. Although Santa Anna was elected president in 1846, he refused to govern, leaving that to his vice president, while he sought to engage with Taylor's forces. With the restored federal republic, some states refused to support the national military campaign led by Santa Anna, who had fought with them directly in the previous decade. Santa Anna urged Vice President Gómez Farías to act as a dictator to get the men and materiel needed for the war. Gómez Farías forced a loan from the Catholic Church, but the funds were not available in time to support Santa Anna's army.

Reaction in the United States

Opposition to the war

In the United States, increasingly divided by sectional rivalry, the war was a partisan issue and an essential element in the origins of the American Civil War. Most Whigs in the North and South opposed it; most Democrats supported it. Southern Democrats, animated by a popular belief in Manifest Destiny, supported it in hope of adding slave-owning territory to the South and avoiding being outnumbered by the faster-growing North. John L. O'Sullivan, editor of the Democratic Review, coined this phrase in its context, stating that it must be "our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions."

Northern antislavery elements feared the expansion of the Southern Slave Power; Whigs generally wanted to strengthen the economy with industrialization, not expand it with more land. Among the most vocal opposing the war in the House of Representatives was former U.S. President John Quincy Adams, a representative of Massachusetts. Adams had first voiced concerns about expanding into Mexican territory in 1836 when he opposed Texas annexation following its de facto independence from Mexico. He continued this argument in 1846 for the same reason. War with Mexico would add new slavery territory to the nation. When the question to go to war with Mexico came to a vote on May 13, 1846, Adams spoke a resounding "No!" in the chamber. Only 13 others followed his lead. Despite that opposition, he later voted for war appropriations.

Ex-slave Frederick Douglass opposed the war and was dismayed by the weakness of the anti-war movement. "The determination of our slave holding president, and the probability of his success in wringing from the people, men and money to carry it on, is made evident by the puny opposition arrayed against him. None seem willing to take their stand for peace at all risks."

Polk was generally able to manipulate Whigs into supporting appropriations for the war but only once it had already started and then "clouding the situation with a number of false statements about Mexican actions." Not everyone went along. Joshua Giddings led a group of dissenters in Washington D.C. He called the war with Mexico "an aggressive, unholy, and unjust war" and voted against supplying soldiers and weapons. He said: "In the murder of Mexicans upon their own soil, or in robbing them of their country, I can take no part either now or hereafter. The guilt of these crimes must rest on others. I will not participate in them."

Fellow Whig Abraham Lincoln contested Polk's causes for the war. Polk had said that Mexico had "shed American blood upon American soil". Lincoln submitted eight "Spot Resolutions", demanding that Polk state the exact spot where Thornton had been attacked and American blood shed, and to clarify whether that location was American soil or if it had been claimed by Spain and Mexico. Lincoln, too, did not actually stop money for men or supplies in the war effort.

Whig Senator Thomas Corwin of Ohio gave a long speech indicting presidential war in 1847. In the Senate February 11, 1847, Whig leader Robert Toombs of Georgia declared: "This war is nondescript ... We charge the President with usurping the war-making power ... with seizing a country ... which had been for centuries, and was then in the possession of the Mexicans. ... Let us put a check upon this lust of dominion. We had territory enough, Heaven knew." Democratic Representative David Wilmot introduced the Wilmot Proviso, which would prohibit slavery in new territory acquired from Mexico. Wilmot's proposal passed the House but not the Senate.

Northern abolitionists attacked the war as an attempt by slave-owners to strengthen the grip of slavery and thus ensure their continued influence in the federal government. Prominent artists and writers opposed the war, including James Russell Lowell, whose works on the subject "The Present Crisis" and the satirical The Biglow Papers were immediately popular. Transcendentalist writers Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson also criticized the war. Thoreau, who served jail time for refusing to pay a tax that would support the war effort, turned a lecture into an essay now known as Civil Disobedience. Emerson was succinct, predicting that, "The United States will conquer Mexico, but it will be as a man who swallowed the arsenic which brings him down in turn. Mexico will poison us." Events proved him right, in a fashion, as arguments over the expansion of slavery in the lands seized from Mexico would fuel the drift to civil war just a dozen years later. The New England Workingmen's Association condemned the war, and some Irish and German immigrants defected from the U.S. Army and formed the Saint Patrick's Battalion to fight for Mexico.

Support of the war

Besides alleging that the actions of Mexican military forces within the disputed boundary lands north of the Rio Grande constituted an attack on American soil, the war's advocates viewed the territories of New Mexico and California as only nominally Mexican possessions with very tenuous ties to Mexico. They saw the territories as unsettled, ungoverned, and unprotected frontier lands, whose non-aboriginal population represented a substantial American component. Moreover, the territories were feared by Americans to be under imminent threat of acquisition by America's rival on the continent, the British.

President Polk reprised these arguments in his Third Annual Message to Congress on December 7, 1847. He scrupulously detailed his administration's position on the origins of the conflict, the measures the U.S. had taken to avoid hostilities, and the justification for declaring war. He also elaborated upon the many outstanding financial claims by American citizens against Mexico and argued that, in view of the country's insolvency, the cession of some large portion of its northern territories was the only indemnity realistically available as compensation. This helped to rally congressional Democrats to his side, ensuring passage of his war measures and bolstering support for the war in the U.S.

U.S. journalism during the war

The Mexican–American War was the first U.S. war that was covered by mass media, primarily the penny press, and was the first foreign war covered primarily by U.S. correspondents. Press coverage in the United States was characterized by support for the war and widespread public interest and demand for coverage of the conflict. Mexican coverage of the war (both written by Mexicans and Americans based in Mexico) was affected by press censorship, first by the Mexican government and later by the American military.

Walt Whitman enthusiastically endorsed the war in 1846 and showed his disdainful attitude toward Mexico and boosterism for Manifest Destiny: "What has miserable, inefficient Mexico—with her superstition, her burlesque upon freedom, her actual tyranny by the few over the many—what has she to do with the great mission of peopling the new world with a noble race? Be it ours, to achieve that mission!"

The coverage of the war was an important development in the U.S., with journalists as well as letter-writing soldiers giving the public in the U.S. "their first-ever independent news coverage of warfare from home or abroad." During the war, inventions such as the telegraph created new means of communication that updated people with the latest news from the reporters on the scene. The most important of these was George Wilkins Kendall, a Northerner who wrote for the New Orleans Picayune, and whose collected Dispatches from the Mexican War constitute an important primary source for the conflict. With more than a decade's experience reporting urban crime, the "penny press" realized the public's voracious demand for astounding war news. Moreover, Shelley Streetby demonstrates that the print revolution, which preceded the U.S.-Mexican War, made it possible for the distribution of cheap newspapers throughout the country. This was the first time in U.S. history that accounts by journalists instead of opinions of politicians had great influence in shaping people's opinions about and attitudes toward a war. Along with written accounts of the war, war artists provided a visual dimension to the war at the time and immediately afterward. Carl Nebel's visual depictions of the war are well known.

By getting constant reports from the battlefield, Americans became emotionally united as a community. News about the war caused extraordinary popular excitement. In the spring of 1846, news about Taylor's victory at Palo Alto brought up a large crowd that met in the cotton textile town of Lowell, Massachusetts. In Chicago, a large concourse of citizens gathered in April 1847 to celebrate the victory of Buena Vista. New York celebrated the twin victories at Veracruz and Buena Vista in May 1847. Generals Taylor and Scott became heroes for their people and later became presidential candidates. Polk had pledged to be a one-term president, but his last official act was to attend Taylor's inauguration as president.

U.S. invasions on Mexico's periphery

New Mexico campaign

After the declaration of war on May 13, 1846, United States Army General Stephen W. Kearny moved southwest from Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in June 1846 with about 1,700 men in his Army of the West. Kearny's orders were to secure the territories Nuevo México and Alta California.

In Santa Fe, Governor Manuel Armijo wanted to avoid battle, but on August 9, Colonel Diego Archuleta and militia officers Manuel Chaves and Miguel Pino forced him to muster a defense. Armijo set up a position in Apache Canyon, a narrow pass about 10 miles (16 km) southeast of the city. However, on August 14, before the American army was even in view, he decided not to fight. An American named James Magoffin claimed he had convinced Armijo and Archuleta to follow this course; an unverified story says he bribed Armijo. When Pino, Chaves, and some of the militiamen insisted on fighting, Armijo ordered the cannon pointed at them. The New Mexican army retreated to Santa Fe, and Armijo fled to Chihuahua.

Kearny and his troops encountered no Mexican forces when they arrived on August 15. Kearny and his force entered Santa Fe and claimed the New Mexico Territory for the United States without a shot fired. Kearny declared himself the military governor of the New Mexico Territory on August 18 and established a civilian government. American officers drew up a temporary legal system for the territory called the Kearny Code.

Kearny then took the remainder of his army west to Alta California; he left Colonel Sterling Price in command of U.S. forces in New Mexico. He appointed Charles Bent as New Mexico's first territorial governor. Following Kearny's departure, dissenters in Santa Fe plotted a Christmas uprising. When the plans were discovered by the U.S. authorities, the dissenters postponed the uprising. They attracted numerous Indian allies, including Puebloans, who also wanted to push the Americans from the territory. On the morning of January 19, 1847, the insurrectionists began the revolt in Don Fernando de Taos, present-day Taos, New Mexico, which later gave it the name the Taos Revolt. They were led by Pablo Montoya, a New Mexican, and Tomás Romero, a Taos pueblo Indian also known as Tomasito (Little Thomas).

Romero led a Native American force to the house of Governor Charles Bent, where they broke down the door, shot Bent with arrows, and scalped him in front of his family. They moved on, leaving Bent still alive. With his wife Ignacia and children, and the wives of friends Kit Carson and Thomas Boggs, the group escaped by digging through the adobe walls of their house into the one next door. When the insurgents discovered the party, they killed Bent but left the women and children unharmed.

The next day a large armed force of approximately 500 New Mexicans and Pueblo attacked and laid siege to Simeon Turley's mill in Arroyo Hondo, several miles outside of Taos. Charles Autobees, an employee at the mill, saw the men coming. He rode to Santa Fe for help from the occupying U.S. forces. Eight to ten mountain men were left at the mill for defense. After a day-long battle, only two of the mountain men survived, John David Albert and Thomas Tate Tobin, Autobees' half-brother. Both escaped separately on foot during the night. The same day New Mexican insurgents killed seven American traders passing through the village of Mora. At most, 15 Americans were killed in both actions on January 20.

The U.S. military moved quickly to quash the revolt; Colonel Price led more than 300 U.S. troops from Santa Fe to Taos, together with 65 volunteers, including a few New Mexicans, organized by Ceran St. Vrain, the business partner of William and Charles Bent. Along the way, the combined forces beat back a force of some 1,500 New Mexicans and Pueblo at Santa Cruz de la Cañada and at Embudo Pass. The insurgents retreated to Taos Pueblo, where they took refuge in the thick-walled adobe church. During the ensuing battle, the U.S. breached a wall of the church and directed cannon fire into the interior, inflicting many casualties and killing about 150 rebels. They captured 400 more men after close hand-to-hand fighting. Only seven Americans died in the battle.

A separate force of U.S. troops under captains Israel R. Hendley and Jesse I. Morin campaigned against the rebels in Mora. The First Battle of Mora ended in a New Mexican victory. The Americans attacked again in the Second Battle of Mora and won, which ended their operations against Mora. New Mexican rebels engaged U.S. forces three more times in the following months. The actions are known as the Battle of Red River Canyon, the Battle of Las Vegas, and the Battle of Cienega Creek. After the U.S. forces won each battle, the New Mexicans and Indians ended open warfare.

California campaign

Word of Congress' declaration of war reached California by August 1846. American consul Thomas O. Larkin, stationed in Monterey, worked successfully during the events in that vicinity to avoid bloodshed between Americans and the Mexican military garrison commanded by General José Castro, the senior military officer in California.

Captain John C. Frémont, leading a U.S. Army topographical expedition to survey the Great Basin, entered Sacramento Valley in December 1845. Frémont's party was at Upper Klamath Lake in the Oregon Territory when it received word that war between Mexico and the U.S. was imminent; the party then returned to California.

Mexico had issued a proclamation that unnaturalized foreigners were no longer permitted to have land in California and were subject to expulsion. With rumors swirling that General Castro was massing an army against them, American settlers in the Sacramento Valley banded together to meet the threat. On June 14, 1846, 34 American settlers seized control of the undefended Mexican government outpost of Sonoma to forestall Castro's plans. One settler created the Bear Flag and raised it over Sonoma Plaza. Within a week, 70 more volunteers joined the rebels' force, which grew to nearly 300 in early July. This event, led by William B. Ide, became known as the Bear Flag Revolt.

On June 25, Frémont's party arrived to assist in an expected military confrontation. San Francisco, then called Yerba Buena, was occupied by the Bear Flaggers on July 2. On July 5, Frémont's California Battalion was formed by combining his forces with many of the rebels.

Commodore John D. Sloat, commander of the U.S. Navy's Pacific Squadron, near Mazatlan, Mexico, had received orders to seize San Francisco Bay and blockade California ports when he was positive that war had begun. Sloat set sail for Monterey, reaching it on July 1. Sloat, upon hearing of the events in Sonoma and Frémont's involvement, erroneously believed Frémont to be acting on orders from Washington and ordered his forces to occupy Monterey on July 7 and raise the U.S. flag. On July 9, 70 sailors and Marines landed at Yerba Buena and raised the American flag. Later that day in Sonoma, the Bear Flag was lowered, and the American flag was raised in its place.

On Sloat's orders, Frémont brought 160 volunteers to Monterey, in addition to the California Battalion. On July 15, Sloat transferred his command of the Pacific Squadron to Commodore Robert F. Stockton, who was more militarily aggressive. He mustered the willing members of the California Battalion into military service with Frémont in command. Stockton ordered Frémont to San Diego to prepare to move northward to Los Angeles. As Frémont landed, Stockton's 360 men arrived in San Pedro. General Castro and Governor Pío Pico wrote farewells and fled separately to the Mexican state of Sonora.

Stockton's army entered Los Angeles unopposed on August 13, whereupon he sent a report to the secretary of state that "California is entirely free from Mexican dominion." Stockton, however, left a tyrannical officer in charge of Los Angeles with a small force. The Californios under the leadership of José María Flores, acting on their own and without federal help from Mexico, in the Siege of Los Angeles, forced the American garrison to retreat on September 29. They also forced small U.S. garrisons in San Diego and Santa Barbara to flee.

Captain William Mervine landed 350 sailors and Marines at San Pedro on October 7. They were ambushed and repulsed at the Battle of Dominguez Rancho by Flores' forces in less than an hour. Four Americans died, with 8 severely injured. Stockton arrived with reinforcements at San Pedro, which increased the American forces there to 800. He and Mervine then set up a base of operations at San Diego.

Meanwhile, Kearny and his force of about 115 men, who had performed a grueling march across the Sonoran Desert, crossed the Colorado River in late November 1846. Stockton sent a 35-man patrol from San Diego to meet them. On December 7, 100 lancers under General Andrés Pico (brother of the governor), tipped off and lying in wait, fought Kearny's army of about 150 at the Battle of San Pasqual, where 22 of Kearny's men (one of whom later died of wounds), including three officers, were killed in 30 minutes of fighting. The wounded Kearny and his bloodied force pushed on until they had to establish a defensive position on "Mule Hill". However, General Pico kept the hill under siege for four days until a 215-man American relief force arrived.

Frémont and the 428-man California Battalion arrived in San Luis Obispo on December 14 and Santa Barbara on December 27. On December 28, a 600-man American force under Kearny began a 150-mile march to Los Angeles. Flores then moved his ill-equipped 500-man force to a 50-foot-high bluff above the San Gabriel River. On January 8, 1847, the Stockton-Kearny army defeated the Californio force in the two-hour Battle of Rio San Gabriel. That same day, Frémont's force arrived at San Fernando. The next day, January 9, the Stockton-Kearny forces fought and won the Battle of La Mesa. On January 10, the U.S. Army entered Los Angeles to no resistance.

On January 12, Frémont and two of Pico's officers agreed to terms for a surrender. Articles of Capitulation were signed on January 13 by Frémont, Andrés Pico and six others at a ranch at Cahuenga Pass (modern-day North Hollywood). This became known as the Treaty of Cahuenga, which marked the end of armed resistance in California.

Pacific Coast campaign

Entering the Gulf of California, Independence, Congress, and Cyane seized La Paz, then captured and burned the small Mexican fleet at Guaymas on October 19, 1847. Within a month, they cleared the gulf of hostile ships, destroying or capturing 30 vessels. Later, their sailors and Marines captured the port of Mazatlán on November 11, 1847. After upper California was secure, most of the Pacific Squadron proceeded down the California coast, capturing all major cities of the Baja California Territory and capturing or destroying nearly all Mexican vessels in the Gulf of California.

A Mexican campaign under Manuel Pineda Muñoz to retake the various captured ports resulted in several small clashes and two sieges in which the Pacific Squadron ships provided artillery support. U.S. garrisons remained in control of the ports. Following reinforcement, Lt. Col. Henry S. Burton marched out. His forces rescued captured Americans, captured Pineda, and on March 31 defeated and dispersed remaining Mexican forces at the Skirmish of Todos Santos, unaware that the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo had been signed in February 1848 and a truce agreed to on March 6. When the U.S. garrisons were evacuated to Monterey following the treaty ratification, many Mexicans went with them: those who had supported the U.S. cause and had thought Lower California would also be annexed along with Upper California.

Northeastern Mexico

- Battle of Monterrey

Led by Zachary Taylor, 2,300 U.S. troops crossed the Rio Grande after some initial difficulties in obtaining river transport. His soldiers occupied the city of Matamoros, then Camargo (where the soldiery suffered the first of many problems with disease) and then proceeded south and besieged the city of Monterrey, Nuevo León. The hard-fought Battle of Monterrey resulted in serious losses on both sides. The U.S. light artillery was ineffective against the stone fortifications of the city, as the American forces attacked in frontal assaults. The Mexican forces under General Pedro de Ampudia repulsed Taylor's best infantry division at Fort Teneria.

American soldiers, including many West Point graduates, had never engaged in urban warfare before, and they marched straight down the open streets, where they were annihilated by Mexican defenders well-hidden in Monterrey's thick adobe homes. They quickly learned, and two days later, they changed their urban warfare tactics. Texan soldiers had fought in a Mexican city before (the Siege of Béxar in December 1835) and advised Taylor's generals that the Americans needed to "mouse hole" through the city's homes. They needed to punch holes in the side or roofs of the homes and fight hand to hand inside the structures. Mexicans called the Texas soldiers the Diabólicos Tejanos (the Devil Texans). This method proved successful. Eventually, these actions drove and trapped Ampudia's men into the city's central plaza, where howitzer shelling forced Ampudia to negotiate. Taylor agreed to allow the Mexican Army to evacuate and to an eight-week armistice in return for the surrender of the city. Taylor broke the armistice and occupied the city of Saltillo, southwest of Monterrey. Santa Anna blamed the loss of Monterrey and Saltillo on Ampudia and demoted him to command a small artillery battalion. Similarly, Polk blamed Taylor both for suffering heavy losses and failing to imprison Ampudia's entire force. Taylor's army was subsequently stripped of most of its troops in order to support the coming coastal operations by Scott against Veracruz and the Mexican heartland.

- Battle of Buena Vista

On February 22, 1847, having heard of this weakness from the written orders found on an ambushed U.S. scout, Santa Anna seized the initiative and marched Mexico's entire army north to fight Taylor with 20,000 men, hoping to win a smashing victory before Scott could invade from the sea. The two armies met and fought the largest battle of the war at the Battle of Buena Vista. Taylor, with 4,600 men, had entrenched at a mountain pass called La Angostura, or "the narrows", several miles south of Buena Vista ranch. Santa Anna, having little logistics to supply his army, suffered desertions all the long march north and arrived with only 15,000 men in a tired state.

Having demanded and been refused the surrender of the U.S. Army, Santa Anna's army attacked the next morning, using a ruse in the battle with the U.S forces. Santa Anna flanked the U.S. positions by sending his cavalry and some of his infantry up the steep terrain that made up one side of the pass, while a division of infantry attacked frontally to distract and draw out the U.S. forces along the road leading to Buena Vista. Furious fighting ensued, during which the U.S. troops were nearly routed, but managed to cling to their entrenched position, thanks to the Mississippi Rifles, a volunteer regiment led by Jefferson Davis, who formed them into a defensive V formation. The Mexicans had nearly broken the American lines at several points, but their infantry columns, navigating the narrow pass, suffered heavily from the American horse artillery, which fired point-blank canister shots to break up the attacks.

Initial reports of the battle, as well as propaganda from the Santanistas, credited the victory to the Mexicans, much to the joy of the Mexican populace, but rather than attack the next day and finish the battle, Santa Anna retreated, losing men along the way, having heard word of rebellion and upheaval in Mexico City. Taylor was left in control of part of northern Mexico, and Santa Anna later faced criticism for his withdrawal. Mexican and American military historians alike agree that the U.S. Army could likely have been defeated if Santa Anna had fought the battle to its finish.

Polk mistrusted Taylor, who he felt had shown incompetence in the Battle of Monterrey by agreeing to the armistice. Taylor later used the Battle of Buena Vista as the centerpiece of his successful 1848 presidential campaign.

Northwestern Mexico

Northwestern Mexico was essentially tribal Indian territory, but on November 21, 1846, the Bear Springs Treaty was signed, ending a large-scale insurrection by the Ute, Zuni, Moquis, and Navajo tribes. In December 1846, after the successful conquest of New Mexico, part of Kearney's Army of the West, the First Missouri Mounted Volunteers, moved into modern-day northwest Mexico. They were led by Alexander W. Doniphan, continuing what ended up being a year-long 5,500 mile campaign. It was described as rivaling Xenophon's march across Anatolia during the Greco-Persian Wars.

On Christmas day, they won the Battle of El Brazito, outside the modern-day El Paso, Texas. On March 1, 1847, Doniphan occupied Chihuahua City. British consul John Potts did not want to allow Doniphan to search Governor Trías's mansion and unsuccessfully asserted it was under British protection. American merchants in Chihuahua wanted the American force to stay in order to protect their business. Major William Gilpin advocated a march on Mexico City and convinced a majority of officers, but Doniphan subverted this plan. Then in late April, Taylor ordered the First Missouri Mounted Volunteers to leave Chihuahua and join him at Saltillo. The American merchants either followed or returned to Santa Fe. Along the way, the townspeople of Parras enlisted Doniphan's aid against an Indian raiding party that had taken children, horses, mules, and money. The Missouri Volunteers finally made their way to Matamoros, from which they returned to Missouri by water.

The civilian population of northern Mexico offered little resistance to the American invasion, possibly because the country had already been devastated by Comanche and Apache Indian raids. Josiah Gregg, who was with the American army in northern Mexico, said "the whole country from New Mexico to the borders of Durango is almost entirely depopulated. The haciendas and ranchos have been mostly abandoned, and the people chiefly confined to the towns and cities."

Southern Mexico

Southern Mexico had a large indigenous population and was geographically distant from the capital, over which the central government had weak control. Yucatán in particular had closer ties to Cuba and to the United States than it did to central Mexico. On a number of occasions in the early era of the Mexican Republic, Yucatán seceded from the federation. There were also rivalries between regional elites, with one faction based in Mérida and the other in Campeche. These issues factored into the Mexican–American War, as the U. S. had designs on this part of the coast.

The U.S. Navy contributed to the war by controlling the coast and clearing the way for U.S. troops and supplies, especially to Mexico's main port of Veracruz. Even before hostilities began in the disputed northern region, the U.S. Navy created a blockade. Given the shallow waters of that portion of the coast, the U.S. Navy needed ships with a shallow draft rather than large frigates. Since the Mexican Navy was almost non-existent, the U.S. Navy could operate unimpeded in gulf waters. The U.S. fought two battles in Tabasco in October 1846 and in June 1847.

In 1847, the Maya revolted against the Mexican elites of the peninsula in a caste war known as the Caste War of Yucatan. Jefferson Davis, then a senator from Mississippi, argued in Congress that the president needed no further powers to intervene in Yucatan since the war with Mexico was underway. Davis's concern was strategic and part of his vision of Manifest Destiny, considering the Gulf of Mexico "a basin of water belonging to the United States" and "the cape of Yucatan and the island of Cuba must be ours". In the end, the U.S. did not intervene in Yucatán, but it had figured in congressional debates about the Mexican–American War. At one point, the government of Yucatán petitioned the U.S. for protection during the Caste War, but the U.S. did not respond.

Scott's invasion of Mexico's heartland

Landings and siege of Veracruz

Rather than reinforce Taylor's army for a continued advance, President Polk sent a second army under General Winfield Scott. Polk had decided that the way to bring the war to an end was to invade the Mexican heartland from the coast. General Scott's army was transported to the port of Veracruz by sea to begin an invasion to take the Mexican capital. On March 9, 1847, Scott performed the first major amphibious landing in U.S. history in preparation for a siege. A group of 12,000 volunteer and regular soldiers successfully offloaded supplies, weapons, and horses near the walled city using specially designed landing crafts. Included in the invading force were several future generals: Robert E. Lee, George Meade, Ulysses S. Grant, James Longstreet, and Thomas "Stonewall" Jackson.

Veracruz was defended by Mexican General Juan Morales with 3,400 men. Mortars and naval guns under Commodore Matthew C. Perry were used to reduce the city walls and harass defenders. The bombardment on March 24, 1847, opened in the walls of Veracruz a thirty-foot gap. The defenders in the city replied with their own artillery, but the extended barrage broke the will of the Mexicans, who faced a numerically superior force, and they surrendered the city after 12 days under siege. U.S. troops suffered 80 casualties, while the Mexicans had around 180 killed and wounded, with hundreds of civilians killed. During the siege, the U.S. soldiers began to fall victim to yellow fever.

Advance on Puebla

Santa Anna allowed Scott's army to march inland, counting on yellow fever and other tropical diseases to take their toll before Santa Anna chose a place to engage the enemy. Mexico had used this tactic before, including when Spain attempted to reconquer Mexico in 1829. Disease could be a decisive factor in the war. Santa Anna was from Veracruz, so he was on his home territory, knew the terrain, and had a network of allies. He could draw on local resources to feed his hungry army and gain intelligence on the enemy's movements. From his experience in the northern battles on open terrain, Santa Anna sought to negate the U.S. Army's primary advantage, its use of artillery.

Santa Anna chose Cerro Gordo as the place to engage the U.S. troops, calculating the terrain would offer the maximum advantage for the Mexican forces. Scott marched westward on April 2, 1847, toward Mexico City with 8,500 initially healthy troops, while Santa Anna set up a defensive position in a canyon around the main road and prepared fortifications. Santa Anna had entrenched with what the U.S. Army believed were 12,000 troops but in fact was around 9,000. He had artillery trained on the road where he expected Scott to appear. However, Scott had sent 2,600 mounted dragoons ahead, and they reached the pass on April 12. The Mexican artillery prematurely fired on them and therefore revealed their positions, beginning the skirmish.

Instead of taking the main road, Scott's troops trekked through the rough terrain to the north, setting up his artillery on the high ground and quietly flanking the Mexicans. Although by then aware of the positions of U.S. troops, Santa Anna and his troops were unprepared for the onslaught that followed. In the battle fought on April 18, the Mexican army was routed. The U.S. Army suffered 400 casualties, while the Mexicans suffered over 1,000 casualties with 3,000 taken prisoner. In August 1847, Captain Kirby Smith, of Scott's 3rd Infantry, reflected on the resistance of the Mexican army:

They can do nothing and their continued defeats should convince them of it. They have lost six great battles; we have captured six hundred and eight cannon, nearly one hundred thousand stands of arms, made twenty thousand prisoners, have the greatest portion of their country and are fast advancing on their Capital which must be ours,—yet they refuse to treat [i.e., negotiate terms]!

The U.S. Army had expected a quick collapse of the Mexican forces. Santa Anna, however, was determined to fight to the end, and Mexican soldiers continued to regroup after battles to fight yet again.

Pause at Puebla

On May 1, 1847, Scott pushed on to Puebla, the second-largest city in Mexico. The city capitulated without resistance. The Mexican defeat at Cerro Gordo had demoralized Puebla's inhabitants, and they worried about harm to their city and inhabitants. It was standard practice in Western warfare for victorious soldiers to be let loose to inflict horrors on civilian populations if they resisted; the threat of this was often used as a bargaining tool to secure surrender without a fight. Scott had orders which aimed to prevent his troops from such violence and atrocities. Puebla's ruling elite also sought to prevent violence, as did the Catholic Church, but Puebla's poor and working-class wanted to defend the city. U.S. Army troops who strayed outside at night were often killed. Enough Mexicans were willing to sell supplies to the U.S. Army to make local provisioning possible. During the following months, Scott gathered supplies and reinforcements at Puebla and sent back units whose enlistments had expired. Scott also made strong efforts to keep his troops disciplined and treat the Mexican people under occupation justly, to keep good order and prevent any popular uprising against his army.

Advance on Mexico City and its capture

With guerrillas harassing his line of communications back to Veracruz, Scott decided not to weaken his army to defend Puebla but, leaving only a garrison at Puebla to protect the sick and injured recovering there, advanced on Mexico City on August 7 with his remaining force. The capital was laid open in a series of battles around the right flank of the city defenses, the Battle of Contreras and Battle of Churubusco. After Churubusco, fighting halted for an armistice and peace negotiations, which broke down on September 6, 1847. With the subsequent battles of Molino del Rey and of Chapultepec, and the storming of the city gates, the capital was occupied. Scott became military governor of occupied Mexico City. His victories in this campaign made him an American national hero.