The social determinants of health (SDOH) are the economic and social conditions that influence individual and group differences in health status. They are the health promoting factors found in one's living and working conditions (such as the distribution of income, wealth, influence, and power), rather than individual risk factors (such as behavioral risk factors or genetics) that influence the risk for a disease, or vulnerability to disease or injury. The distributions of social determinants are often shaped by public policies that reflect prevailing political ideologies of the area.

The World Health Organization says that "the social determinants can be more important than health care or lifestyle choices in influencing health." and "This unequal distribution of health-damaging experiences is not in any sense a 'natural' phenomenon but is the result of a toxic combination of poor social policies, unfair economic arrangements [where the already well-off and healthy become even richer and the poor who are already more likely to be ill become even poorer], and bad politics."

Issues of particular focus are social determinants of mental health, social determinants of health in poverty and social determinants of obesity.

Historical development

Starting in the early 2000s, the World Health Organization facilitated the academic and political work on social determinants in a way that provided a deep understanding of health disparities in a global perspective.

In 2003, the World Health Organization (WHO) Europe suggested that the social determinants of health included: the social gradient, stress, early life, social exclusion, work, unemployment, social support, addiction, food, and transportation.

In 2008, the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health published a report entitled "Closing the Gap in a Generation", which aimed to understand, from a social justice perspective, how health inequity could be remedied, and what actions could combat factors that exacerbated injustices. The work of the commission was based on development goals, and thus, connected SDH (social determinants of health) discourse to economic growth and bridging gaps in the healthcare system. This report identified two broad areas of social determinants of health that needed to be addressed. The first area was daily living conditions, which included healthy physical environments, fair employment, and decent work, social protection across the lifespan, and access to health care. The second major area was distribution of power, money, and resources, including equity in health programs, public financing of action on the social determinants, economic inequalities, resource depletion, healthy working conditions, gender equity, political empowerment, and a balance of power and prosperity of nations.

The 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) established by the Obama administration in the United States, embodied the ideas put in place by the WHO by bridging the gap between community-based health and healthcare as a medical treatment, meaning that a larger consideration of social determinants of health was emerging in the policy. The ACA established community change through initiatives like providing Community Transformation Grants to community organizations, which opened up further debates and talks about increased integration of policies to create change on a larger scale.

The 2011 World Conference on Social Determinants of Health, in which 125 delegations participated, created the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health. With a series of affirmations and announcements, the Declaration aimed to communicate that the social conditions in which an individual exists were key to understanding health disparities that individual may face, and it called for new policies across the world to fight health disparities, along with global collaborations.

Commonly accepted social determinants

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines social determinants of health as "life-enhancing resources, such as food supply, housing, economic and social relationships, transportation, education, and health care, whose distribution across populations effectively determines length and quality of life." These include access to care and resources such as food, insurance coverage, income, housing, and transportation.

According to a report by the Center for Migration Studies of New York, the different social determinants of health are strongly correlated. People living in an area with one identified determinant also tend to be affected by other determinants. Social determinants of health influence health-promoting behaviors, and health equity among the population is not possible without equitable distribution of social determinants among groups.

A commonly used model that illustrate the relationship between biological, individual, community, and societal determinants is Whitehead and Dahlgren's model originally presented in 1991 and has been adapted by the CDC. Additionally, within the United States, the Healthy People 2030 is an objective-driven framework which can guide public health practitioners and healthcare providers on how to address social determinants of health at the community level.

In Canada, these social determinants of health have gained wide usage: Income and income distribution; Education; Unemployment and job security; Employment and working conditions; Early childhood development; Food insecurity; Housing; Social exclusion/inclusion; Social safety network; Health services; Aboriginal status; Gender; Race; Disability.

The list of social determinants of health can be much longer. A recently published article identified several other social determinants. Unfortunately, there is no agreed taxonomy or criteria as to what should be considered a social determinant of health. In the literature, a subjective assessment—whether social factors impacting health are avoidable through structural changes in policy and practice—seems to be the dominant way of identifying a social determinant of health. The increase of artificial intelligence (AI) being used in clinical care raises numerous opportunities for addressing health equity issues, yet clear models and procedures for data characteristics and design have not been embraced consistently across health systems and providers.

Gender

The World Health Organization (WHO) has defined health as "a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity." Identified by the 2012 World Development Report as one of two key human capital endowments, health can influence an individual's ability to reach his or her full potential in society. Yet while gender equality has made the most progress in areas such as education and labor force participation, health inequality between men and women continues to harm many societies to this day.

While both males and females face health disparities, women have historically experienced a disproportionate amount of health inequity. This stems from the fact that many cultural ideologies and practices have created a structured patriarchal society where women are vulnerable to abuse and mistreatment. Additionally, women are typically restricted from receiving certain opportunities such as education and paid labor that can help improve their accessibility to better health care resources. Females are also frequently underrepresented or excluded from mixed-sex clinical trials and therefore subjected to physician bias in diagnosis and treatment.Race

Race and health refers to how being identified with a specific race influences health. Race is a complex concept that has changed across chronological eras and depends on both self-identification and social recognition. In the study of race and health, scientists organize people in racial categories depending on different factors such as: phenotype, ancestry, social identity, genetic makeup and lived experience. "Race" and ethnicity often remain undifferentiated in health research.

Differences in health status, health outcomes, life expectancy, and many other indicators of health in different racial and ethnic groups are well documented. Epidemiological data indicate that racial groups are unequally affected by diseases, in terms or morbidity and mortality. Some individuals in certain racial groups receive less care, have less access to resources, and live shorter lives in general. Overall, racial health disparities appear to be rooted in social disadvantages associated with race such as implicit stereotyping and average differences in socioeconomic status.

Health disparities are defined as "preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by socially disadvantaged populations". According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, they are intrinsically related to the "historical and current unequal distribution of social, political, economic and environmental resources".

The relationship between race and health has been studied from multidisciplinary perspectives, with increasing focus on how racism influences health disparities, and how environmental and physiological factors respond to one another and to genetics.Ongoing debates

Steven H. Woolf, MD of the Virginia Commonwealth University Center on Human Needs states, "The degree to which social conditions affect health is illustrated by the association between education and mortality rates." Reports in 2005 revealed the mortality rate was 206.3 per 100,000 for adults aged 25 to 64 years with little education beyond high school, but was twice as great (477.6 per 100,000) for those with only a high school education and three times as great (650.4 per 100,000) for those less educated. Based on the data collected, the social conditions such as education, income, and race were dependent on one another, but these social conditions also apply to independent health influences.

Marmot and Bell of the University College London found that in wealthy countries, income and mortality are correlated as a marker of relative position within society, and this relative position is related to social conditions that are important for health including good early childhood development, access to high quality education, rewarding work with some degree of autonomy, decent housing, and a clean and safe living environment. The social condition of autonomy, control, and empowerment turns are important influences on health and disease, and individuals who lack social participation and control over their lives are at a greater risk for heart disease and mental illness.

Early childhood development can be promoted or disrupted as a result of the social and environmental factors effecting the mother, while the child is still in the womb. Janet Currie's research finds that women in New York City receiving assistance from the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), in comparison to their previous or future childbirth, are 5.6% less likely to give birth to a child who is underweight, an indication that a child will have better short term, and long term physical, and cognitive development.

Several other social determinants are related to health outcomes and public policy, and are easily understood by the public to impact health. They tend to cluster together – for example, those living in poverty experience a number of negative health determinants.

International health inequalities

Even in the wealthiest countries, there are health inequalities between the rich and the poor. Researchers Labonte and Schrecker from the Department of Epidemiology and Community Medicine at the University of Ottawa emphasize that globalization is key to understanding the social determinants of health, and as Bushra (2011) posits, the impacts of globalization are unequal. Globalization has caused an uneven distribution of wealth and power both within and across national borders, and where and in what situation a person is born has an enormous impact on their health outcomes. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development found significant differences among developed nations in health status indicators such as life expectancy, infant mortality, incidence of disease, and death from injuries. Migrants and their family members also experience significant negatives health impacts.

These inequalities may exist in the context of the health care system, or in broader social approaches. According to the WHO's Commission on Social Determinants of Health, access to health care is essential for equitable health, and it argued that health care should be a common good rather than a market commodity. However, there is substantial variation in health care systems and coverage from country to country. The commission also calls for government action on such things as access to clean water and safe, equitable working conditions, and it notes that dangerous working conditions exist even in some wealthy countries. In the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health, several key areas of action were identified to address inequalities, including promotion of participatory policy-making processes, strengthening global governance and collaboration, and encouraging developed countries to reach a target of 0.7% of gross national product (GNP) for official development assistance.

Theoretical approaches

The UK Black and The Health Divide reports considered two primary mechanisms for understanding how social determinants influence health: cultural/behavioral and materialist/structuralist The cultural/behavioral explanation is that individuals' behavioral choices (e.g., tobacco and alcohol use, diet, physical activity, etc.) were responsible for their development and deaths from a variety of diseases. However, both the Black and Health Divide reports found that behavioral choices are determined by one's material conditions of life, and these behavioral risk factors account for a relatively small proportion of variation in the incidence and death from various diseases.

The materialist/structuralist explanation emphasizes the people's material living conditions. These conditions include availability of resources to access the amenities of life, working conditions, and quality of available food and housing among others. Within this view, three frameworks have been developed to explain how social determinants influence health. These frameworks are: (a) materialist; (b) neo-materialist; and (c) psychosocial comparison. The materialist view explains how living conditions – and the social determinants of health that constitute these living conditions – shape health. The neo-materialist explanation extends the materialist analysis by asking how these living conditions occur. The psychosocial comparison explanation considers whether people compare themselves to others and how these comparisons affect health and wellbeing.

A nation's wealth is a strong indicator of the health of its population. Within nations, however, individual socio-economic position is a powerful predictor of health. Material conditions of life determine health by influencing the quality of individual development, family life and interaction, and community environments. Material conditions of life lead to differing likelihood of physical (infections, malnutrition, chronic disease, and injuries), developmental (delayed or impaired cognitive, personality, and social development), educational (learning disabilities, poor learning, early school leaving), and social (socialization, preparation for work, and family life) problems. Material conditions of life also lead to differences in psychosocial stress. When the fight-or-flight reaction is chronically elicited in response to constant threats to income, housing, and food availability, the immune system is weakened, insulin resistance is increased, and lipid and clotting disorders appear more frequently. The effects of chronic fight-or-flight is described in the allostatic load model.

The materialist approach offers insight into the sources of health inequalities among individuals and nations. Adoption of health-threatening behaviors is also influenced by material deprivation and stress. Environments influence whether individuals take up tobacco, use alcohol, consume poor diets, and have low levels of physical activity. Tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, and carbohydrate-dense diets are also used to cope with difficult circumstances. The materialist approach seeks to understand how these social determinants occur.

The neo-materialist approach is concerned with how nations, regions, and cities differ on how economic and other resources are distributed among the population. This distribution of resources can vary widely from country to country. The neo-materialist view focuses on both the social determinants of health and the societal factors that determine the distribution of these social determinants, and especially emphasizes how resources are distributed among members of a society.

The social comparison approach holds that the social determinants of health play their role through citizens' interpretations of their standings in the social hierarchy. There are two mechanisms by which this occurs. At the individual level, the perception and experience of one's status in unequal societies lead to stress and poor health. Feelings of shame, worthlessness, and envy can lead to harmful effects upon neuro-endocrine, autonomic and metabolic, and immune systems. Comparisons to those of a higher social class can also lead to attempts to alleviate such feelings by overspending, taking on additional employment that threaten health, and adopting health-threatening coping behaviors such as overeating and using alcohol and tobacco. At the communal level, widening and strengthening of hierarchy weakens social cohesion, which is a determinant of health. The social comparison approach directs attention to the psychosocial effects of public policies that weaken the social determinants of health. However, these effects may be secondary to how societies distribute material resources and provide security to its citizens, which are described in the materialist and neo-materialist approaches.

Life-course perspective

Life-course approaches emphasize the accumulated effects of experience across the life span in understanding the maintenance of health and the onset of disease. The economic and social conditions – the social determinants of health – under which individuals live their lives have a cumulative effect upon the probability of developing any number of diseases, including heart disease and stroke. Studies into the childhood and adulthood antecedents of adult-onset diabetes show that adverse economic and social conditions across the life span predispose individuals to this disorder.

Hertzman outlines three health effects that have relevance for a life-course perspective. Latent effects are biological or developmental early life experiences that influence health later in life. Low birth weight, for instance, is a reliable predictor of incidence of cardiovascular disease and adult-onset diabetes in later life. Nutritional deprivation during childhood has lasting health effects as well.

Pathway effects are experiences that set individuals onto trajectories that influence health, well-being, and competence over the life course. As one example, children who enter school with delayed vocabulary are set upon a path that leads to lower educational expectations, poor employment prospects, and greater likelihood of illness and disease across the lifespan. Deprivation associated with poor-quality neighborhoods, schools, and housing sets children off on paths that are not conducive to health and well-being.

Cumulative effects are the accumulation of advantage or disadvantage over time that manifests itself in poor health, in particular between women and men. These involve the combination of latent and pathways effects. Adopting a life-course perspective directs attention to how social determinants of health operate at every level of development – in utero, infancy, early childhood, childhood, adolescence, and adulthood – to both immediately influence health and influence it in the future.

Chronic stress and health

Stress is hypothesized to be a major influence in the social determinants of health. There is a relationship between experience of chronic stress and negative health outcomes. This relationship is explained through both direct and indirect effects of chronic stress on health outcomes.

The direct relationship between stress and health outcomes is the effect of stress on human physiology. The long term stress hormone, cortisol, is believed to be the key driver in this relationship. Chronic stress has been found to be significantly associated with chronic low-grade inflammation, slower wound healing, increased susceptibility to infections, and poorer responses to vaccines. Meta-analysis of healing studies has found that there is a robust relationship between elevated stress levels and slower healing for many different acute and chronic conditions However, it is also important to note that certain factors, such as coping styles and social support, can mitigate the relationship between chronic stress and health outcomes.

Stress can also be seen to have an indirect effect on health status. One way this happens is due to the strain on the psychological resources of the stressed individual. Chronic stress is common in those of a low socio-economic status, who are having to balance worries about financial security, how they will feed their families, housing status, and many other concerns. Therefore, individuals with these kinds of worries may lack the emotional resources to adopt positive health behaviors. Chronically stressed individuals may therefore be less likely to prioritize their health.

In addition to this, the way that an individual responds to stress can influence their health status. Often, individuals responding to chronic stress will develop potentially positive or negative coping behaviors. People who cope with stress through positive behaviors such as exercise or social connections may not be as affected by the relationship between stress and health, whereas those with a coping style more prone to over-consumption (i.e. emotional eating, drinking, smoking or drug use) are more likely to be see negative health effects of stress. Vape shops are also found more in low socioeconomic status areas. The owners target these areas in particular to gain profit. Since people with low-income status are not highly educated, they are more prone to make poor health behavior choices. Socioeconomic status also has a huge impact in lives of people of color. According to Kids Count Data Center, Children in Poverty 2014, in the United States 39% of African American children and adolescents, and 33% of Latino children and adolescents are living in poverty (Kids Count Data Center, Children in Poverty 2014). The stress these racial groups with low socioeconomic status face, is higher than the same race group from a high-income community. According to the research done on socioeconomic disparities in vape shop density and proximity to public schools, the researchers found that vape shops were located a lot more in the areas with schools where African-Americans/Latinos/Hispanic students were in higher population than the areas with schools where White population was more.

The detrimental effects of stress on health outcomes are hypothesized to partly explain why countries that have high levels of income inequality have poorer health outcomes compared to more equal countries. Wilkinson and Picket hypothesized in their book The Spirit Level that the stressors associated with low social status are amplified in societies where others are clearly far better off.

A landmark study conducted by the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization found that exposure to long working hours, operating through psychosocial stress, is the occupational risk factor with the largest attributable burden of disease, i.e. an estimated 745,000 fatalities from ischemic heart disease and stroke events in 2016.

Improving health conditions worldwide

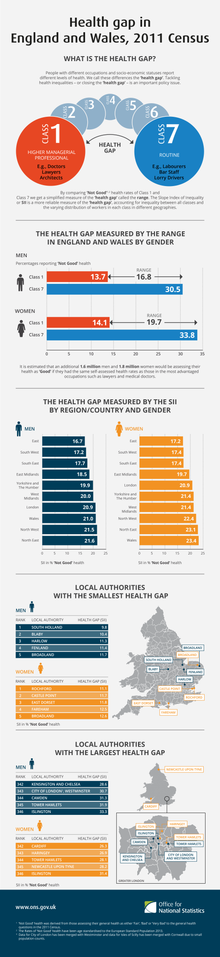

Reducing the health gap requires that governments build systems that allow a healthy standard of living for every resident.

Interventions

Three common interventions for improving social determinant outcomes as identified by the WHO are education, social security and urban development. However, evaluation of interventions has been difficult due to the nature of the interventions, their impact and the fact that the interventions strongly affect children's health outcomes.

- Education: Many scientific studies have been conducted and strongly suggests that increased quantity and quality of education leads to benefits to both the individual and society (e.g. improved labor productivity). Health and economic outcome improvements can be seen in health measures such as blood pressure, crime, and market participation trends. Examples of interventions include decreasing size of classes and providing additional resources to low-income school districts. However, there is currently insufficient evidence to support education as a social determinants intervention with a cost-benefit analysis.

- Social Protection: Interventions such as “health-related cash transfers”, maternal education, and nutrition-based social protections have been shown to have a positive impact on health outcomes. However, the full economic costs and impacts generated of social security interventions are difficult to evaluate, especially as many social protections primarily affect children of recipients. The landmark Cochrane Collaboration Review of the health impact of unconditional cash transfers in low- and middle-income countries found a large body of evidence that these cash transfers clinically meaningfully reduce in the likelihood of being sick (by an estimated 27%), may also improve food security and dietary diversity, and may also reduce extreme poverty and improve school attendance, as well as increase healthcare spending.

- Urban Development: Urban development interventions include a wide variety of potential targets such as housing, transportation, and infrastructure improvements. The health benefits are considerable (especially for children), because housing improvements such as smoke alarm installation, concrete flooring, removal of lead paint, etc. can have a direct impact on health. In addition, there is a fair amount of evidence to prove that external urban development interventions such as transportation improvements or improved walkability of neighborhoods (which is highly effective in developed countries) can have health benefits. Affordable housing options (including public housing) can make large contributions to both social determinants of health, as well as the local economy, and access to public natural areas -including green and blue spaces- is also associated with improved health benefits.

The Commission on Social Determinants of Health made recommendations in 2005 for action to promote health equity based on three principles: "improve the circumstances in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age; tackle the inequitable distribution of power, money, and resources, the structural drivers of conditions of daily life, globally, nationally, and locally; and measure the problem, evaluate action, and expand the knowledge base." These recommendations would involve providing resources such as quality education, decent housing, access to affordable health care, access to healthy food, and safe places to exercise for everyone despite gaps in affluence. Expansion of knowledge of the social determinants of health, including among healthcare workers, can improve the quality and standard of care for people who are marginalized, poor or living in developing nations by preventing early death and disability while working to improve quality of life.

Challenges of measuring value of interventions

Many economic studies have been conducted to measure the effectiveness and value of social determinant interventions but are unable to accurately reflect effects on public health due to the multi-faceted nature of the topic. While neither cost-effectiveness nor cost-utility analysis is able to be used on social determinant interventions, cost-benefit analysis is able to better capture the effects of an intervention on multiple sectors of the economy. For example, tobacco interventions have shown to decrease tobacco use, but also prolong lifespans, increasing lifetime healthcare costs and is therefore marked as a failed intervention by cost-effectiveness, but not cost-benefit. Another issue with research in this area is that most of the current scientific papers focus on rich, developed countries, and there is a lack of research in developing countries.

Policy changes that affect children also present the challenge that it takes a significant amount of time to gather this type of data. In addition, policies to reduce child poverty are particularly important, as elevated stress hormones in children interfere with the development of brain circuitry and connections, causing long term chemical damage. In most wealthy countries, the relative child poverty rate is 10 percent or less; in the United States, it is 21.9 percent. The lowest poverty rates are more common in smaller well-developed and high-spending welfare states like Sweden and Finland, with about 5 or 6 percent. Middle-level rates are found in major European countries where unemployment compensation is more generous and social policies provide more generous support to single mothers and working women (through paid family leave, for example), and where social assistance minimums are high. For instance, the Netherlands, Austria, Belgium and Germany have poverty rates that are in the 7 to 8 percent range.

Within clinical settings

Connecting patients with the necessary social services during their visits to hospitals or medical clinics is an important factor in preventing patients from experiencing decreased health outcomes as a result of social or environmental factors.

A clinical study done by researchers at the University of California San Francisco, indicated that connecting patients with the resources to utilize and contact social services during clinical visits, significantly decreased families social needs and significantly improved children's overall health.

In addition, within the clinical setting, it was noted that in order to better health outcomes for the patients in any clinical setting, a collection of SHD data should be documented. This helps maintain the connection between healthcare systems and organizations that address these needs that were documented.

Public policy

The Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health embraces a transparent, participatory model of policy development that, among other things, addresses the social determinants of health leading to persistent health inequalities for indigenous peoples. In 2017, citing the need for accountability for the pledges made by countries in the Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health, the World Health Organization and United Nations Children's Fund called for the monitoring of intersectoral interventions on the social determinants of health that improve health equity.

The United States Department of Health and Human Services includes social determinants in its model of population health, and one of its missions is to strengthen policies which are backed by the best available evidence and knowledge in the field. Social determinants of health do not exist in a vacuum. Their quality and availability to the population are usually a result of public policy decisions made by governing authorities. For example, early life is shaped by availability of sufficient material resources that assure adequate educational opportunities, food, and housing among others. Much of this has to do with the employment security and the quality of working conditions and wages. The availability of quality, regulated childcare is an especially important policy option in support of early life. These are not issues that usually come under individual control but rather they are socially constructed conditions which require institutional responses. A policy-oriented approach places such findings within a broader policy context. In this context, Health in All Policies has seen as a response to incorporate health and health equity into all public policies as means to foster synergy between sectors and ultimately promote health.

Yet it is not uncommon to see governmental and other authorities individualize these issues. Governments may view early life as being primarily about parental behaviors towards their children. They then focus upon promoting better parenting, assist in having parents read to their children, or urge schools to foster exercise among children rather than raising the amount of financial or housing resources available to families. Indeed, for every social determinant of health, an individualized manifestation of each is available. There is little evidence to suggest the efficacy of such approaches in improving the health status of those most vulnerable to illness in the absence of efforts to modify their adverse living conditions.

A team of the Cochrane Collaboration conducted the first comprehensive systematic review of the health impact of unconditional cash transfers, as an increasingly common up-stream, structural social determinant of health. The review of 21 studies, including 16 randomized controlled trials, found that unconditional cash transfers may not improve health services use. However, they lead to a large, clinically meaningful reduction in the likelihood of being sick by an estimated 27%. Unconditional cash transfers may also improve food security and dietary diversity. Children in recipient families are more likely to attend school, and the cash transfers may increase money spent on health care.

One of the recommendations by the Commission on the Social Determinants of Health is expanding knowledge – particularly to health care workers.

Although not addressed by the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health, sexual orientation and gender identity are increasingly recognized as social determinants of health.

With all the different health inequities and differences in quality of care addressed in social determinants of health, the American Hospital Association created the Value Initiative project which helps make healthcare more affordable to people of all types. It does this four different ways:

- It frames issues regarding the healthcare system and its pricing and affordability.

- It provides knowledge, resources, and tools for hospitals to supply affordable healthcare and increase value.

- The initiative collects data of hospital experiences to develop new federal policy solutions.

- Builds a platform for the American Hospital Association to discuss with policymakers to find solutions to the lack of affordable care.

This initiative educates the public and makes sure there is transparency in pricing of hospital bills, making sure patients are not billed more than they should be. It also addresses the cost drivers in the healthcare system, and urges for legislators to take action to make healthcare affordable and to prioritize health over profit. This organization asks congress to control the rising costs of pharmaceuticals by encouraging competition between manufacturers, and improving transparency in drug pricing. In this value initiative, they have started the Affordability Advocacy Agenda (AAA) which improves the ongoing policy and advocacy activities. With the Covid-19 pandemic health care spending increased and there was a rise in hospitalizations and therefore a rise in demand for health care providers. The price for care has increased and there aren't enough workers to meet the demand for care. The AAA and congress are working together to provide relief from the pandemic in order to make healthcare more affordable to all.

As of January 1, 2022 there are regulations placed for healthcare providers about no surprise billing. This is the "No Surprises Act" of division BB of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2021 and this rule was made by the Biden-Harris administration. Patients should not be billed more than they expected to pay, it is often noticed with emergency services and this rule will stop patients from getting worried about any bills out of their budget, and they will be able to get the proper care they need for their health with peace of mind. The act was passed by congress at the end of 2020 and offers protection against insured Americans getting surprise bills from out-of-network providers. They struggled to find an amount that an insurer should pay to the out-of-network provider, but eventually found an amount and the law is now in effect as of January 2022. When it comes to out-of-network providers, patients often rely on these services in an emergency and then get stuck with the bill afterwards. Air Ambulance bills are a big problem for consumers, not just because they are out of network and cost a lot, but also for their lack of billing transparency. Since the Airline Deregulation Act, which allows air ambulance to make their own prices, federal solutions to this increasing cost of emergency care is needed. A possible solution is to allow air ambulance services to be administered and financed in a way that combines competitive bidding and public utility regulation.