American Indian boarding schools, also known more recently as American Indian residential schools, were established in the United States from the mid-17th to the early 20th centuries with a primary objective of "civilizing" or assimilating Native American children and youth into European American culture. In the process, these schools denigrated Native American culture and made children give up their languages and religion. At the same time the schools provided a basic Western education. These boarding schools were first established by Christian missionaries of various denominations. The missionaries were often approved by the federal government to start both missions and schools on reservations, especially in the lightly populated areas of the West. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries especially, the government paid religious orders to provide basic education to Native American children on reservations, and later established its own schools on reservations. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) also founded additional off-reservation boarding schools based on the assimilation model. These sometimes drew children from a variety of tribes. In addition, religious orders established off-reservation schools.

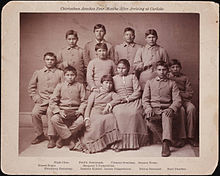

Children were typically immersed in European American culture. Schools forced removal of indigenous cultural signifiers: cutting the children's hair, having them wear American-style uniforms, forbidding them from speaking their mother tongues, and replacing their tribal names with English language names (saints names under some religious orders) for use at the schools, as part of assimilation and to Christianize them. The schools were usually harsh, especially for younger children who had been forcibly separated from their families and forced to abandon their Native American identities and cultures. Children sometimes died in the school system due to infectious disease. Investigations of the later 20th century revealed cases of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse occurring mostly in church-run schools.

Summarizing recent scholarship from Native perspectives, Dr. Julie Davis said:

Boarding schools embodied both victimization and agency for Native people and they served as sites of both cultural loss and cultural persistence. These institutions, intended to assimilate Native people into mainstream society and eradicate Native cultures, became integral components of American Indian identities and eventually fueled the drive for political and cultural self-determination in the late 20th century.

Since those years, tribal nations have carried out political activism and gained legislation and federal policy that gives them the power to decide how to use federal education funds, how they educate their children, and the authority to establish their own community-based schools. Tribes have also founded numerous tribal colleges and universities on reservations. Tribal control over their schools has been supported by federal legislation and changing practices by the BIA. By 2007, most of the boarding schools had been closed down, and the number of Native American children in boarding schools had declined to 9,500.

Although there are hundreds of deceased Indigenous children yet to be found, investigations are increasing across the United States.

History of education of Native Americans by Europeans

... instead of exterminating a part of the human race ... we had persevered ... and at last had imparted our Knowledge of cultivating and the arts, to the Aboriginals of the Country ... But it has been conceived to be impracticable to civilize the Indians of North America – This opinion is probably more convenient than just.

— Henry Knox to George Washington, 1789.

In the late eighteenth century, reformers starting with President George Washington and Henry Knox, in efforts to "civilize" or otherwise assimilate Native Americans, adopted the practice of assimilating Native American children in current American culture. At the time the society was dominated by agriculture, with many yeomen subsistence farmers, and rural society made up of some small towns and few large cities. The Civilization Fund Act of 1819 promoted this policy by providing funding to societies (mostly religious missionaries) who worked on Native American education, often at schools established in or near Native American communities. The reformers believed this policy would help the Indians survive increasing contact with European-American settlers who were moving west into their territories.

Moses Tom sent his children to an Indian boarding school.

I rejoice, brothers, to hear you propose to become cultivators of the earth for the maintenance of your families. Be assured you will support them better and with less labor, by raising stock and bread, and by spinning and weaving clothes, than by hunting. A little land cultivated, and a little labor, will procure more provisions than the most successful hunt; and a woman will clothe more by spinning and weaving, than a man by hunting. Compared with you, we are but as of yesterday in this land. Yet see how much more we have multiplied by industry, and the exercise of that reason which you possess in common with us. Follow then our example, brethren, and we will aid you with great pleasure ...

— President Thomas Jefferson, Brothers of the Choctaw Nation, December 17, 1803

Early mission schools

In 1634, Fr. Andrew White of the English Province of the Society of Jesus established a mission in what is now Southern Maryland. He said the purpose of the mission, as an interpreter told the chief of a Native American tribe there, was "to extend civilization and instruction to his ignorant race, and show them the way to heaven." The mission's annual records report that by 1640, they had founded a community they named St. Mary's. Native Americans were sending their children there to be educated, including the daughter of Tayac, the Pascatoe chief. She was likely an exception because of her father's status, as girls were generally not educated with boys in English Catholic schools of the period. Other students discussed in the records were male.

The same records report that in 1677,

"a school for humanities was opened by our Society in the centre of Maryland, directed by two of the Fathers; and the native youth, applying themselves assiduously to study, made good progress. Maryland and the recently established school sent two boys to St. Omer who yielded in abilities to few Europeans, when competing for the honour of being first in their class. So that not gold, nor silver, nor the other products of the earth alone, but men also are gathered from thence to bring those regions, which foreigners have unjustly called ferocious, to a higher state of virtue and cultivation."

In the mid-1600s, Harvard College had an "Indian College" on its campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts Bay Colony, supported by the Anglican Society for Propagation of the Gospel. Its few Native American students came from New England. In this period higher education was very limited for all classes, and most 'colleges' taught at a level more similar to today's high schools. In 1665, Caleb Cheeshahteaumuck, "from the Wampanoag...did graduate from Harvard, the first Indian to do so in the colonial period".

In the early colonial years, other Indian schools were created by local New England communities, as with the Indian school in Hanover, New Hampshire, in 1769. This gradually developed as Dartmouth College, which has retained some programs for Native Americans. Other schools were also created in the East, such as in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania by Moravian missionaries. Religious missionaries from various denominations developed the first schools as part of their missions near indigenous settlements, believing they could extend education and Christianity to Native Americans. East of the Appalachian Mountains, most Indians had been forced off their traditional lands before the American Revolutionary War. They had few reservations.

In the early nineteenth century, the new republic continued to deal with questions about how Native American peoples would live. The Foreign Mission School, a Protestant-backed institution that opened in Cornwall, Connecticut in 1816, was set up for male students from a variety of non-Christian peoples, mostly abroad. Native Hawaiians, Muslim and Hindu students from India and Southeast Asia were among the nearly 100 total who attended during its decade of operation. Also enrolled were Native American students from the Cherokee and Choctaw tribes (among the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast), as well as Lenape (a mid-Atlantic tribe) and Osage students. It was intended to train young people as missionaries, interpreters, translators, etc. who could help guide their peoples.

Nationhood, Indian Wars, and western settlement

Through the 19th century, the encroachment of European Americans on Indian lands continued. From the 1830s, tribes from both the Southeast and the Great Lakes areas were pushed west of the Mississippi, forced off their lands to Indian Territory. As part of the treaties signed for land cessions, the United States was supposed to provide education to the tribes on their reservations. Some religious orders and organizations established missions in Kansas and what later became Oklahoma to work on these new reservations. Some of the Southeast tribes established their own schools, as the Choctaw did for both girls and boys.

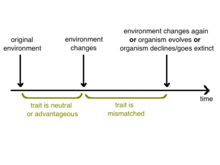

After the Civil War and decades of Indian Wars in the West, more tribes were forced onto reservations after ceding vast amounts of land to the US. With the goal of assimilation, believed necessary so that tribal Indians could survive to become part of American society, the government increased its efforts to provide education opportunities. Some of this was related to the progressive movement, which believed the only way for the tribal peoples to make their way was to become assimilated, as American society was rapidly changing and urbanizing.

Following the Indian Wars, missionaries founded additional schools in the West with boarding facilities. Given the vast areas and isolated populations, they could support only a limited number of schools. Some children necessarily had to attend schools that were distant from their communities. Initially under President Ulysses S. Grant, only one religious organization or order was permitted on any single reservation. The various denominations lobbied the government to be permitted to set up missions, even in competition with each other.

Assimilation-era day schools

Day schools were also created to implement federal mandates. Compared to boarding schools, day schools were a less expensive option that usually received less parental pushback.

One example is the Fallon Indian Day School opened on the Stillwater Indian Reservation in 1908. Even after the process of closing boarding schools started, day schools remained open.

Carlisle Indian Industrial School

After the Indian Wars, Lieutenant Richard Henry Pratt was assigned to supervise Native prisoners of war at Fort Marion which was located in St. Augustine, Florida. The United States Army sent seventy-two warriors from the Cheyenne, Kiowa, Comanche and Caddo nations, to exile in St. Augustine, Florida. They were used as hostages to encourage their peoples in the West to remain peaceful.

Pratt began to work with them on education in European-American culture, essentially a kind of immersion. While he required changes: the men had to cut their hair and wear common uniforms rather than their traditional clothes, he also granted them increased autonomy and the ability to govern themselves within the prison. Pleased by his success, he was said to have supported the motto, "Kill the Indian, Save the Man." Pratt said in a speech in 1892:

"A great general has said that the only good Indian is a dead one. In a sense, I agree with the sentiment, but only in this: that all the Indian there is in the race should be dead."

Pratt provided for some of the younger men to pursue more education at the Hampton Institute, a historically black college founded in 1868 for the education of freedmen by biracial representatives of the American Missionary Association soon after the Civil War. Following Pratt's sponsored students, Hampton in 1875 developed a program for Native American students.

Pratt continued the assimilation model in developing the Carlisle Indian Industrial School. Pratt felt that within one generation Native children could be integrated into Euro-American culture. With this perspective he proposed an expensive experiment to the federal government. Pratt wanted the government to fund a school that would require Native children to move away from their homes to attend a school far away. The Carlisle Indian school, which became the template for over 300 schools across the United States, opened in 1879. Carlisle Barracks an abandoned Pennsylvanian military base was used for the school. It became the first school that was not on a reservation.

The Carlisle curriculum was heavy based on the culture and society of rural America. The classes included vocational training for boys and domestic science for girls. Students worked to carry out chores that helped sustain the farm and food production for the self-supporting school. They were also able to produce goods to sell at the market. Carlisle students produced a newspaper, had a well-regarded chorus and orchestra, and developed sports programs. In the summer students often lived with local farm families and townspeople, reinforcing their assimilation, and providing labor at low cost to the families..

Federally supported boarding schools

Carlisle and its curriculum became the model for the Bureau of Indian Affairs. By 1902 it authorized 25 federally funded off-reservation schools in 15 states and territories, with a total enrollment of over 6,000 students. Federal legislation required Native American children to be educated according to Anglo-American standards. Parents had to authorize their children's attendance at boarding schools and, if they refused, officials could use coercion to gain a quota of students from any given reservation.

Boarding schools were also established on reservations, where they were often operated by religious missions or institutes, which were generally independent of the local diocese, in the case of Catholic orders. Because of the distances, often Native American children were separated from their families and tribes when they attended such schools on other reservations. At the peak of the federal program, the BIA supported 350 boarding schools.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when students arrived at boarding schools, their lives altered dramatically. They were given short haircuts (a source of shame for boys of many tribes, who considered long hair part of their maturing identity), required to wear uniforms, and to take English names for use at the school. Sometimes the names were based on their own; other times they were assigned at random. The children were not allowed to speak their own languages, even between each other. They were required to attend church services and were often baptized as Christians. As was typical of the time, discipline was stiff in many schools. It often included assignment of extra chores for punishment, solitary confinement and corporal punishment, including beatings by teachers using sticks, rulers and belts.

Anna Moore said, regarding the Phoenix Indian School:

If we were not finished [scrubbing the dining room floors] when the 8 a.m. whistle sounded, the dining room matron would go around strapping us while we were still on our hands and knees.

Abuse in the boarding schools

The children who were admitted into boarding schools experienced several forms of abuse. They were given white names, forced to speak English, and were not allowed to practice their culture. They took classes on how to conduct manual labor such as farming and housekeeping. When they were not in class, they were expected to maintain the upkeep of the schools. Unclean and overpopulated living conditions led to the spread of disease and many students did not receive enough food. Bounties were offered for students who tried to run away and many students committed suicide. Students who died were sometimes placed in coffins and buried in the school cemetery by their own classmates.

Indigenous children were forcibly removed from their families and admitted to these boarding schools. Their cultural traditions were discarded when they were taught about American ideas of refinement and civilization. This forced assimilation increased substance abuse and suicides among these students as they suffered mental illnesses such as depression and PTSD. These illnesses also increased the risk of developing cardiovascular diseases.

The sexual abuse of indigenous children in boarding schools was perpetrated by the administrators of these programs. Teachers, nuns, and priests performed these acts upon their students. Children were touched and molested to be used as pleasure by these mentors who were supposed to educate them. Several mentors considered these students as objects and sexually abused them by forming rotations to switch in and out whenever they were done sexually tormenting the next student. These adults also used sexual abuse as a form of embarrassment towards each other. In tracing the path of violence, several students experienced an assault that, "can only be described as unconscionable, it was a violation not only of a child's body but an assault on their spirit". This act created a majority among the children who were victims in silence. This recurred in boarding schools across the nation in different scenarios. These include boys being sexually assaulted on their 13th birthdays to girls being forcibly taken at night by the priest to be used as objects.

As claimed by Dr. Jon Reyhner, he described methods of discipline by mentioning that: "The boys were laid on an empty barrel and whipped with a long leather strap". Methods such as these have left physical injuries and made the institutions dangerous for these children as they lived in fear of violence. Many children did not recover from their wounds caused by abuse from as they were often left untreated.

Legality and policy

In 1776, the Continental Congress authorized the Indian commissioners to engage ministers as teachers to work with Indians. This movement increased after the War of 1812.

In 1819, Congress appropriated $10,000 to hire teachers and maintain schools. These resources were allocated to the missionary church schools because the government had no other mechanism to educate the Indian population.

In 1887, to provide funding for more boarding schools, Congress passed the Compulsory Indian Education Act.

In 1891, a compulsory attendance law enabled federal officers to forcibly take Native American children from their homes and reservations. The American government believed they were rescuing these children from a world of poverty and depression and teaching them "life skills".

Tabatha Toney Booth of the University of Central Oklahoma wrote in her paper, Cheaper Than Bullets,

"Many parents had no choice but to send their kids, when Congress authorized the Commissioner of Indian Affairs to withhold rations, clothing, and annuities of those families that refused to send students. Some agents even used reservation police to virtually kidnap youngsters, but experienced difficulties when the Native police officers would resign out of disgust, or when parents taught their kids a special "hide and seek" game. Sometimes resistant fathers found themselves locked up for refusal. In 1895, nineteen men of the Hopi Nation were imprisoned to Alcatraz because they refused to send their children to boarding school.

Between 1778 and 1871, the federal government signed 389 treaties with American Indian tribes. Most of these treaties contained provisions that the federal government would provide education and other services in exchange for land. The last of these treaties, the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, established the Great Sioux Reservation. One particular article in the Fort Laramie Treaty illustrates the attention the federal government paid to the "civilizing" nature of education: "Article 7. In order to insure the civilization of the Indians entering int this treaty the necessity of education is admitted, especially of such of them as are or may be settled on said agricultural reservations, and they therefore pledge themselves to compel their children, male and female, between the ages of six and sixteen years to attend school"

Use of the English language in the education of American Indian children was first mentioned in the report of the Indian Peace Commission, a body appointed by an act of Congress in 1867. The report stated that the difference of languages was a major problem and advocated elimination of Indian languages and replacement of them with English. This report created a controversy in Indian education because the missionaries who had been responsible for educating Native youth used a bilingual instructional policy. In 1870, President Grant criticized this beginning a new policy with eradication of Native languages as a major goal

In 1871, the United States government prohibited further treaties with Indian nations and also passed the Appropriations Act for Indian Education requiring the establishment of day schools on reservations.

In 1873, the Board of Indian Commissions argued in a Report to Congress that days schools were ineffective at teach Indian children English because they spent 20 hours per day at home speaking their native language. The Senate and House Indian Affairs committees joined in the criticism of day schools a year later arguing that they operated too much to perpetuate "the Indian as special-status individual rather than preparing for him independent citizenship"

"The boarding school movement began after the Civil War, when reformers turned their attention to the plight of Indian people and advocated for proper education and treatment so that Indians could become like other citizens. One of the first efforts to accomplish this goal was the establishment of the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, founded in 1879." The leader of the school, General Pratt also employed the "outing system" which placed Indians in non-Indian homes during the summers and for three years following high school to learn non-Indian culture (ibid). Government subsidies were made to participating families. Pratt believed that this was both educating American Indians and making them Americans. In 1900, 1,880 Carlisle students participated in this system, each with his or her own bank account.

In the late 1800s, the federal government pursued a policy of total assimilation of the American Indian into mainstream American society.

In 1918, Carlisle boarding school was closed because Pratt's method of assimilating American Indian students through off-reservation boarding schools was perceived as outdated. That same year Congress passed new Indian education legislation, the Act of May 25, 1918. It generally forbade expenditures for separate education of children less than 1/4 Indian whose parents are citizens of the United States when they live in an area where adequate free public schools are provided.

Meriam Report of 1928

In 1926, the Department of the Interior (DOI) commissioned the Brookings Institution to conduct a survey of the overall conditions of American Indians and to assess federal programs and policies. The Meriam Report, officially titled The Problem of Indian Administration, was submitted February 21, 1928, to Secretary of the Interior Hubert Work. Related to education of Native American children, it recommended that the government:

- Abolish The Uniform Course of Study, which taught only European-American cultural values;

- Educate younger children at community schools near home, and have older children attend non-reservation schools for higher grade work;

- Have the Indian Service (now Bureau of Indian Affairs) provide American Indians the education and skills they need to adapt both in their own communities and United States society.

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934

The Indian Reorganization Act of 1934 ended the allotment period of history, confirmed the rights to Indian self-government, and made Indians eligible to hold Bureau of Indian Affairs posts, which encouraged Indians to attend vocational schools and colleges." During this period there was an effort to encourage the development of community day schools; however, public school attendance for Indian children was also encouraged. In the same year, the Johnson–O'Malley Act (JOM) was passed, which provided for the reimbursement of states for the cost of educating Indian students in public schools. This federal-state contract provided that a specified sum be paid by the federal government and held the state responsible for the education and welfare of Indians within its boundaries. Funds made available from the O'Malley act were designated to assist in reducing the enrollment of Indian boarding schools, placing them in public schools instead.

The termination period

In 1953, Congress passed House Concurrent Resolution 108, which set a new direction in federal policy toward Indians. The major spokesperson for the resolution Senator Arthur Watkins (Utah), stated: "As rapidly as possible, we should end the status of Indians as wards of the government and grant them all the rights and prerogatives pertaining to American citizenship" The federal government implemented another new policy, aimed at relocating Indian people to urban cities and away from the reservations, terminating the tribes as separate entities. There were sixty-one tribes terminated during that period.

1968 onward

In 1968, President Lyndon B. Johnson ended this practice and the termination period. He also directed the Secretary of the Interior to establish Indian School boards for federal Indian schools to be comprised by members of the communities.

Major legislation aimed at improving Indian education occurred in the 1970s. In 1972, Congress passed the Indian Education Act, which established a comprehensive approach to meeting the unique needs of American Indians and Alaska Native students. This Act recognizes that American Indians have unique educational and culturally related academic needs and distinct language and cultural needs. The most far-reaching legislation to be signed during the 1970s, however, was the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975, which guaranteed tribes the opportunity to determine their own futures and the education of their children through funds allocated to and administrated by individual tribes.

Disease and death

Given the lack of public sanitation and the often crowded conditions at boarding schools in the early 20th-century, students were at risk for infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, measles, and trachoma. None of these diseases was yet treatable by antibiotics or controlled by vaccines, and epidemics swept schools as they did cities.

The overcrowding of the schools contributed to the rapid spread of disease within the schools. "An often-underpaid staff provided irregular medical care. And not least, apathetic boarding school officials frequently failed to heed their own directions calling for the segregation of children in poor health from the rest of the student body". Tuberculosis was especially deadly among students. Many children died while in custody at Indian schools. Often students were prevented from communicating with their families, and parents were not notified when their children fell ill; the schools also failed sometimes to notify them when a child died. "Many of the Indian deaths during the great influenza pandemic of 1918–1919, which hit the Native American population hard, took place in boarding schools."

The 1928 Meriam Report noted that infectious disease was often widespread at the schools due to malnutrition, overcrowding, poor sanitary conditions, and students weakened by overwork. The report said that death rates for Native American students were six and a half times higher than for other ethnic groups. A report regarding the Phoenix Indian School said, "In December of 1899, measles broke out at the Phoenix Indian School, reaching epidemic proportions by January. In its wake, 325 cases of measles, 60 cases of pneumonia, and 9 deaths were recorded in a 10-day period."

Implications of assimilation

From 1810 to 1917, the U.S. federal government subsidized mission and boarding schools. By 1885, 106 Indian schools had been established, many of them on abandoned military installations. Using military personnel and Indian prisoners, boarding schools were seen as a means for the government to achieve assimilation of Native Americans into mainstream American culture. Assimilation efforts included forcibly removing Native Americans from their families, converting them to Christianity, preventing them from learning or practicing indigenous culture and customs, and living in a strict military fashion.

When students arrived at boarding schools, the routine was typically the same. First, the students were forced to give up their tribal clothing and their hair was cut. Second, "[t]o instill the necessary discipline, the entire school routine was organized in martial fashion, and every facet of student life followed a strict timetable".

One student recalled the routine in the 1890s:

A small bell was tapped, and each of the pupils drew a chair from under the table. Supposing this act meant that they were to be seated, I pulled out mine and at once slipped into it from one side. But when I turned my head, I saw that I was the only one seated, and all the rest at our table remained standing. Just as I began to rise, looking shyly around to see how chairs were to be used, a second bell was sounded. All were seated at last, and I had to crawl back into my chair again. I heard a man's voice at one end of the hall, and I looked around to see him. But all the others hung their heads over their plates. As I glanced at the long chain of tables, I cause the eyes of a paleface woman upon me. Immediately I dropped my eyes, wondering why I was so keenly watched by the strange woman. The man ceased his mutterings, and then a third bell was tapped. Everyone picked up his knife and fork and began eating. I began crying instead, for by this time I was afraid to venture anything more.

Besides mealtime routines, administrators "educated" Indigenous students on how to farm using European-based methods, which they considered superior to indigenous methods. Given the constraints of rural locations and limited budgets, boarding schools often operated supporting farms, raising livestock and produced their vegetables and fruit.

From the moment students arrived at school, they could not "be Indian" in any way. Boarding school administrators "forbade, whether in school or on reservation, tribal singing and dancing, along with the wearing of ceremonial and 'savage' clothes, the practice of native religions, the speaking of tribal languages, the acting out of traditional gender roles". School administrators argued that young women needed to be specifically targeted due to their important place in continuing assimilation education in their future homes. Educational administrators and teachers were instructed that "Indian girls were to be assured that, because their grandmothers did things in a certain way, there was no reason for them to do the same".

Removal to reservations in the West in the early part of the century and the enactment of the Dawes Act in 1887 eventually took nearly 50 million acres of land from Indian control. On-reservation schools were either taken over by Anglo leadership or destroyed. Indian-controlled school systems became non-existent while "the Indians [were] made captives of federal or mission education".

Although schools did use verbal correction to enforce assimilation, more violent measures were also used, as corporal punishment was common in European American society. Archuleta et al. (2000) noted cases where students had "their mouths washed out with lye soap when they spoke their native languages; they could be locked up in the guardhouse with only bread and water for other rule violations; and they faced corporal punishment and other rigid discipline on a daily basis". Beyond physical and mental abuse, some school authorities sexually abused students as well.

One former student recounted,

Intimidation and fear were very much present in our daily lives. For instance, we would cower from the abusive disciplinary practices of some superiors, such as the one who yanked my cousin's ear hard enough to tear it. After a nine-year-old girl was raped in her dormitory bed during the night, we girls would be so scared that we would jump into each other's bed as soon as the lights went out. The sustained terror in our hearts further tested our endurance, as it was better to suffer with a full bladder and be safe than to walk through the dark, seemingly endless hallway to the bathroom. When we were older, we girls anguished each time we entered the classroom of a certain male teacher who stalked and molested girls.

Girls and young women taken from their families and placed into boarding schools, such as the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, were urged to accomplish the U.S. federal government's vision of "educating Indian girls in the hope that women trained as good housewives would help their mates assimilate" into U.S. mainstream culture.

Historian Brenda Child asserts that boarding schools cultivated pan-Indian-ism and made possible cross-tribal coalitions that helped many different tribes collaborate in the later 20th century. She argues:

People formerly separated by language, culture, and geography lived and worked together in residential schools. Students formed close bonds and enjoyed a rich cross-cultural change. Graduates of government schools often married former classmates, found employment in the Indian Service, migrated to urban areas, returned to their reservations and entered tribal politics. Countless new alliances, both personal and political, were forged in government boarding schools.

Jacqueline Emery, introducing an anthology of boarding school writings, suggests that these writings prove that the children showed a cultural and personal resilience "more common among boarding school students than one might think". Although school authorities censored the material, it demonstrates multiple methods of resistance to school regimes. Several students educated in boarding schools, such as Gertrude Bonnin, Angel De Cora, Francis La Flesche, and Laura Cornelius Kellogg, became highly educated and were precursors to modern Indigenous activists.

After release or graduation from Indian boarding schools, students were expected to return to their tribes and induce European assimilation there. Many students who returned to their reservations experienced alienation, language and cultural barriers, and confusion, in addition to posttraumatic stress disorder and the legacy of trauma from abuse. They struggled to respect elders, but also met resistance from family and friends when trying to initiate Anglo-American changes.

Everyone in these boarding schools faced hardship but that did not stop them from building their foundation of resistance. Native students utilized what was taught at school to speak up and perform activism. They were very intelligent and resourceful to become knowledgeable in activist and political works. Forcibly being removed from their families, many put up a stance to refuse their kids to be kidnapped from them by hiding them and encouraging them to run away. It has not always been successful but it was a form of resistance that was present during this period.

As mentioned by historians Brian Klopotek and Brenda Child, "A remote Indian population living in Northern Minnesota who, in 1900, took a radical position against the construction of a government school." This Indigenous population is rather known as the Ojibwe people showed hostility to construction happening on their land by expressing armed resistance. The Ojibwe men stood as armed guards surrounding the construction workers and their building indicating the workmen were not welcomed to build on their region of living. This type of armed resistance was common throughout Native society during the boarding school period. Many indigenous communities expressed this rebellion throughout their stolen land.

A famous resistance tactic used by these students in boarding schools was speaking and responding back in their mother tongue. These schools stressed the importance of enforcing the extinction of their first language and adapting to English. Speaking their language symbolized a bond that strictly attached them closer still to their culture. Speaking their mother tongue resulted in physical abuse which was feared but resistance continued in this form to cause frustration. They wanted to show that their roots are deeply rooted in them and cannot be replaced with force. Another form of resistance they used was misbehavior, giving their staff a very hard time. This meant acting very foolish making it hard for them to be handled. Misbehaving meant consistently breaking the rules, acting out of character, and starting fires or fights. This was all an act and a habit to be kicked out of the boarding school and in hopes to be sent home. They wanted to be a huge headache enough to not suffer abuse but to be expelled. Resistance was a form of courage used to go against these boarding schools. These efforts were inspired by each other and from times of colonization. It was a way to keep their mother tongue, culture, and Native identities still attached and restored to civilization. Using resistance tactics helped slow down the intelligence of American culture being understood and taught.

The ongoing effects this event had brought within indigenous communities was hardly forgivable by these various groups. "According to Mary Annette Pember, whose mother was forced to attend St. Mary's Catholic Boarding school in Wisconsin, her mother often recollected, "the beatings, the shaming, and the withholding of food (P.15)." done by the nuns. Thus her mothers lasting effects, the traumatic effects that boarding schools have had continue for generations of Native people who never attended the schools such as families members with surviving and missing loved ones.

When faculty visited former students, they rated their success based on the following criteria: "orderly households, 'citizen's dress', Christian weddings, 'well-kept' babies, land in severalty, children in school, industrious work habits, and leadership roles in promoting the same 'civilized' lifestyles among family and tribe". Many students returned to the boarding schools. General Richard Henry Pratt, an administrator who had founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, began to believe that "[t]o civilize the Indian, get him into civilization. To keep him civilized, let him stay."

Schools in mid-20th century and later changes

Attendance in Indian boarding schools generally increased throughout the first half of the 20th century, doubling by the 1960s. In 1969, the BIA operated 226 schools in 17 states, including on reservations and in remote geographical areas. Some 77 were boarding schools. A total of 34,605 children were enrolled in the boarding schools; 15,450 in BIA day schools; and 3854 were housed in dormitories "while attending public schools with BIA financial support. In addition, 62,676 Indian youngsters attend public schools supported by the Johnson-O'Malley Act, which is administered by BIA."

Enrollment reached its highest point in the 1970s. In 1973, 60,000 American Indian children are estimated to have been enrolled in an Indian boarding school.

The rise of pan-Indian activism, tribal nations' continuing complaints about the schools, and studies in the late 1960s and mid-1970s (such as the Kennedy Report of 1969 and the National Study of American Indian Education) led to passage of the Indian Self-Determination and Education Assistance Act of 1975. This emphasized authorizing tribes to contract with federal agencies in order to take over management of programs such as education. It also enabled the tribes to establish community schools for their children on their reservations.

In 1978, Congress passed and the President signed the Indian Child Welfare Act, giving Native American parents the legal right to refuse their child's placement in a school. Damning evidence related to years of abuses of students in off-reservation boarding schools contributed to the enactment of the Indian Child Welfare Act. Congress approved this act after hearing testimony about life in Indian boarding schools.

As a result of these changes, many large Indian boarding schools closed in the 1980s and early 1990s.[citation needed] Some located on reservations were taken over by tribes. By 2007, the number of American Indian children living in Indian boarding school dormitories had declined to 9,500. This figure includes those in 45 on-reservation boarding schools, seven off-reservation boarding schools, and 14 peripheral dormitories. From 1879 to the present day, it is estimated that hundreds of thousands of Native Americans attended Indian boarding schools as children.

In the early 21st century, about two dozen off-reservation boarding schools still operate, but funding for them has declined.

Native American tribes developed one of the first women's colleges.

21st century

Circa 2020, the Bureau of Indian Education operates approximately 183 schools, primarily non-boarding, and primarily located on reservations. The schools have 46,000 students. Modern criticisms focus on the quality of education provided and compliance with federal education standards. In March 2020 the BIA finalized a rule to create Standards, Assessments and Accountability System (SAAS) for all BIA schools. The motivation behind the rule is to prepare BIA students to be ready for college and careers.

Books about Native American boarding schools

- Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928, author David Wallace Adams (1995)

- Indian Horse, author Richard Wagamese (Ojibwe) (2012)

Movies and documentaries about Native American boarding schools

- Our Spirits Don't Speak English: Indian Boarding School, Documentary produced by Rich-Heape Films (2008)

- The Only Good Indian, 2009 film starring Wes Studi

- Playing for the World, Documentary produced by Montana PBS (2010)

- Our Fires Still Burn, Documentary produced by Audrey Geyer (2013)

- Unspoken: America's Native American Boarding Schools, Documentary produced by KUED (2016)

- Indian Horse, based on the book with the same name written by Richard Wagamese (Ojibwe), produced by Devonshire Productions and Screen Siren Pictures (2017)