From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A high-ranking male

mandrill advertises his status with bright facial coloration.

In biology, a dominance hierarchy (formerly and colloquially called a pecking order) is a type of social hierarchy that arises when members of animal social groups interact, creating a ranking system. A dominant higher-ranking individual is sometimes called an alpha, and the submissive lower-ranking individual a beta.

Different types of interactions can result in dominance depending on

the species, including ritualized displays of aggression or direct

physical violence. In social living groups, members are likely to compete for access to limited resources and mating opportunities.

Rather than fighting each time they meet, relative rank is established

between individuals of the same sex, with higher-ranking individuals

often gaining more access to resources and mates. Based on repetitive

interactions, a social order is created that is subject to change each

time a dominant animal is challenged by a subordinate one.

Definitions

Dominance

is an individual's preferential access to resources over another based

on coercive capacity based on strength, threat, and intimidation,

compared to prestige (persuasive capacity based on skills, abilities,

and knowledge). A dominant animal is one whose sexual,

feeding, aggressive, and other behaviour patterns subsequently occur

with relatively little influence from other group members. Subordinate animals are opposite; their behaviour is submissive, and can be relatively easily influenced or inhibited by other group members.

Dominance

For many animal societies, an individual's position in the dominance

hierarchy corresponds with their opportunities to reproduce.

In hierarchically social animals, dominant individuals may exert

control over others. For example, in a herd of feral goats it is a large

male that is dominant and maintains discipline and coherence of the

flock. He leads the group but shares leadership on a foraging expedition

with a mature she-goat who will normally outlast a succession of

dominant males. However, earlier work showed that leadership orders in goats were not related to age or dominance.

In sheep, position in a moving flock is highly correlated with social

dominance, but there is no definite study to show consistent voluntary

leadership by an individual.

In birds, dominant individuals preferentially select higher perches to

put themselves in the best position to detect and avoid predators, as

well as to display their dominance to other members of their own

species. It has been suggested that decision-taking about the actions of the group is commonly dissociated from social dominance.

When individuals seek high rank

Given

the benefits and costs of possessing a high rank within a hierarchical

group, there are certain characteristics of individuals, groups, and

environments that determine whether an individual will benefit from a

high rank. These include whether or not high rank gives them access to

valuable resources such as mates and food. Age, intelligence,

experience, and physical fitness can influence whether or not an

individual deems it worthwhile to pursue a higher ranking in the

hierarchy, which often comes at the expense of conflict. Hierarchy

results from interactions, group dynamics, and sharing of resources, so

group size and composition affect the dominance decisions of

high-ranking individuals. For example, in a large group with many males,

it may be difficult for the highest-ranking male to dominate all the

mating opportunities, so some mate sharing probably exists. These

opportunities available to subordinates reduce the likelihood of a

challenge to the dominant male: mating is no longer an all-or-nothing

game and the sharing is enough to placate most subordinates. Another

aspect that can determine dominance hierarchies is the environment. In

populations of Kenyan vervet monkeys,

high-ranking females have higher foraging success when the food

resources are clumped, but when food is distributed throughout an area

they lose their advantage, because subordinate females can acquire food

with less risk of encountering a dominant female.

Benefits

Foraging success

A benefit to high-ranking individuals is increased foraging

success and access to food resources. During times of water shortage

the highest-ranking vervet females have greater access than subordinates

females to water in tree holes. In chacma baboons,

the high-ranking males have the first access to vertebrate prey that

has been caught by the group, and in yellow baboons the dominant males

feed for longer without being interrupted.

In many bird species, the dominant individuals have higher rates of food intake. Such species include dark-eyed juncos and oystercatchers.

The dominant individuals in these groups fill themselves up first and

fill up more quickly, so they spend less time foraging, which reduces

the risk of predation. Thus they have increased survival because of

increased nutrition and decreased predation.

Reproductive success

In primates, a well-studied group, high rank brings reproductive success, as seen in a 1991 meta-analysis of 32 studies.

A 2016 study determined that higher status increased reproductive

success amongst men, and that this did not vary by type of subsistence

(foraging, horticulture, pastoralism, agriculture). This contradicts the

"egalitarian hypothesis", which predicts that status would affect

reproductive success more amongst foragers than amongst nonforagers.

High-ranking bonnet macaque

males have more access to fertile females and consequently partake in

most of the matings within the group; in one population, three males

were responsible for over 75% of matings. In this population, males

often vary in rank. As their rank improves, they gain more exclusive

time with fertile females; when their rank decreases, they get less

time. In many primates, including bonnet macaques and rhesus monkeys,

the offspring of high-ranking individuals have better fitness and thus

an increased rate of survival. This is most likely a function of two

factors: The first is that high-ranking males mate with high-ranking

females. Assuming their high rank is correlated with higher fitness and

fighting ability, this trait will be conferred to their offspring. The

second factor is that higher-ranking parents probably provide better

protection to their offspring and thus ensure higher survival rates.

Amongst rhesus macaques, higher-ranking males sired more offspring,

though the alpha male was never the one to sire the most offspring, with

that instead being a high-ranking but not top male. The complex

relationship between rank and reproduction in this species is likely

explained by the fact that rhesus macaques queue, rather than fight, for

dominance, meaning that the alpha male is not necessarily the strongest

or most attractive male.

In rodents, the highest-ranking male frequently sires the most

offspring. The same pattern is found in most carnivores, such as the dwarf mongoose.

The dwarf mongoose lives in a social system with one dominant pair. The

dominant female produces all or almost all of the offspring in the

living group, and the dominant male has first access to her during her

oestrus period. In red deer, the males who experienced winter dominance,

resulting from greater access to preferred foraging sites, had higher

ability to get and maintain larger harems during the mating season.

In many monogamous bird species, the dominant pairs tend to get

the best territories, which in turn promote offspring survival and adult

health. In dunnocks, a species of bird that experiences many mating

systems, sometimes individuals will form a group that will have one

dominant male who achieves all of the mating in the group.

In the monogynous bee species Melipona subnitida,

the queen seeks to maintain reproductive success by preventing workers

from caring for their cells, pushing or hitting them using her antennae.

Workers display aggression towards males, claiming priority over the

cells when males try to use them to place eggs.

Costs of being dominant

There

are costs to being of a high rank in a hierarchical group which offset

the benefits. The most common costs to high-ranking individuals are

higher metabolic rates and higher levels of stress hormones. In great tits and pied flycatchers,

high-ranking individuals experience higher resting metabolic rates and

therefore need to consume more food in order to maintain fitness and

activity levels compared to subordinates in their groups. The energetic

costs of defending territory, mates, and other resources can be very

consuming and cause high-ranking individuals, who spend more time in

these activities, to lose body mass over long periods of dominance.

Therefore, their physical condition decreases the longer they spend

partaking in these high-energy activities, and they lose rank as a

function of age.

In wild male baboons, the highest-ranking male, also known as the

alpha, experiences high levels of both testosterone and glucocorticoid,

which indicates that high-ranking males undergo higher levels of stress

which reduces fitness. Reduced health and longevity occurs because

these two hormones have immunosuppressant activity, which reduces

survival and presents opportunities for parasitic infestation and other

health risks. This reduced fitness due to the alpha position results in

individuals maintaining high rank for shorter periods of time and having

an overall reduced health and longevity from the physical strain and

costs of the position.

Interpersonal complementarity hypothesis

The interpersonal complementarity hypothesis suggests that obedience

and authority are reciprocal, complementary processes. That is, it

predicts that one group member's behaviours will elicit a predictable

set of actions from other group members. Friendly behaviours are

predicted to be met with friendly behaviours, and hostile behaviours are

predicted to be reciprocated with similar, hostile behaviours. When an

individual acts in a dominant, authoritative manner in a group, this

behaviour tends to prompt submissive responses from other group members.

Similarly, when group members display submissive behaviour, others feel

inclined to display dominant behaviours in return. Tiedens and Fragale

(2003) found that hierarchical differentiation plays a significant role

in liking behaviour in groups. Individuals prefer to interact with other

group members whose power, or status behaviour complements their own.

That is to say, group members who behave submissively when talking to

someone who appears to be in control are better liked, and similarly

individuals who display dominant behaviours (e.g., taking charge,

issuing orders) are more liked when interacting with docile, subservient

individuals.

Subordinance

Benefits

Being

subordinate offers a number of benefits. Subordination is beneficial in

agonistic conflicts where rank predicts the outcome of a fight. Less

injury will occur if subordinate individuals avoid fighting with

higher-ranking individuals who would win a large percentage of the time —

knowledge of the pecking order keeps both parties from incurring the

costs of a prolonged fight. In hens, it has been observed that both

dominants and subordinates benefit from a stable hierarchical

environment, because fewer challenges means more resources can be

dedicated to laying eggs. In groups of highly related individuals, kin

selection may influence the stability of hierarchical dominance. A

subordinate individual closely related to the dominant individual may

benefit more genetically by assisting the dominant individual to pass on

their genes.

Alpha male savanna baboons have high levels of testosterone

and stress; over a long period of time, this can lead to decreased

fitness. The lowest-ranking males also had high stress levels,

suggesting that it is the beta males that gain the most fitness,

avoiding stress but receiving some of the benefits of moderate rank.

The mating tactics of savanna baboons are correlated with their age.

Older, subordinate males form alliances to combat higher-ranking males

and get access to females.

Fighting with dominant males is a risky behavior that may result in defeat, injury or even death. In bighorn sheep,

however, subordinates occasionally win a fight for a female, and they

father 44% of the lambs born in the population. These sheep live in

large flocks, and dominance hierarchies are often restructured each

breeding season.

Burying beetles,

which have a social order involving one dominant male controlling most

access to mates, display a behavior known as sneak copulation. While one

male at a carcass has a 5:1 mating advantage, subordinate males will

tempt females away from the carcass with pheromones and attempt to copulate before the dominant male can drive them forcefully away. In flat lizards,

young males take advantage of their underdeveloped secondary sex

characteristics to engage in sneak copulations. These young males mimic

all the visual signs of a female lizard in order to successfully

approach a female and copulate without detection by the dominant male.

This strategy does not work at close range because the chemical signals

given off by the sneaky males reveal their true nature, and they are

chased out by the dominant.

Costs to subordinates

Subordinate

individuals suffer a range of costs from dominance hierarchies, one of

the most notable being reduced access to food sources. When a resource

is obtained, dominant individuals are first to feed as well as taking

the longest time. Subordinates also lose out in shelter and nesting

sites. Brown hyenas,

which display defined linear dominance in both sexes, allow subordinate

males and females decreased time of feeding at a carcass. In toque monkeys

subordinates are often displaced from feeding sites by dominant males.

Additionally, they are excluded from sleeping sites, and they suffer

reduced growth and increased mortality.

Subordinate individuals often demonstrate a huge reproductive

disadvantage in dominance hierarchies. Among brown hyenas, subordinate

females have less opportunity to rear young in the communal den, and

thus had decreased survival of offspring when compared to high-ranking

individuals. Subordinate males have far less copulations with females

compared to the high-ranking males. In African wild dogs

which live in social packs separated into male and female hierarchies,

top-ranking alpha females have been observed to produce 76–81% of all

litters.

Mitigating the costs

Subordinate

animals engage in a number of behaviors in order to outweigh the costs

of low rank. Dispersal is often associated with increased mortality and

subordination may decrease the potential benefits of leaving the group.

In the red fox

it has been shown that subordinate individuals, given the opportunity

to desert, often do not due to the risk of death and the low possibility

that they would establish themselves as dominant members in a new

group.

Conflict over dominance

Animal

decisions regarding involvement in conflict are defined by the

interplay between the costs and benefits of agonistic behaviors. When

initially developed, game theory,

the study of optimal strategies during pair-wise conflict, was grounded

in the false assumption that animals engaged in conflict were of equal

fighting ability. Modifications, however, have provided increased focus

on the differences between the fighting capabilities of animals and

raised questions about their evolutionary development. These differences

are believed to determine the outcomes of fights, their intensity, and

animal decisions to submit or continue fighting. The influence of

aggression, threats, and fighting on the strategies of individuals

engaged in conflict has proven integral to establishing social

hierarchies reflective of dominant-subordinate interactions.

The asymmetries between individuals have been categorized into three types of interactions:

- Resource-holding potential: Animals that are better able to defend resources often win without much physical contact.

- Resource value: Animals more invested in a resource are likely to

invest more in the fight despite potential for incurring higher costs.

- Intruder retreats: When participants are of equal fighting ability and competing for a certain territory,

the resident of the territory is likely to end as the victor because he

values the territory more. This can be explained further by looking at

the example of the common shrews.

If one participant believes he is the resident of the territory, he

will win when the opponent is weaker or food is scarce. However, if both

shrews believe they are the true territory holder, the one with the

greater need for food, and therefore, the one that values the resource

more, is most likely to win.

As expected, the individual who emerges triumphant is rewarded with

the dominant status, having demonstrated their physical superiority.

However, the costs incurred to the defeated, which include loss of

reproductive opportunities and quality food, can hinder the individual's

fitness. In order to minimize these losses, animals generally retreat

from fighting or displaying fighting ability unless there are obvious

cues indicating victory. These often involve characteristics that

provide an advantage during agonistic behavior, such as size of body,

displays, etc. Red stags, for example, engage in exhausting roaring contests to exhibit their strength.

However, such an activity would impose more costs than benefits for

unfit stags, and compel them to retreat from the contest. Larger stags

have also been known to make lower-frequency threat signals, acting as

indicators of body size, strength, and dominance.

Engaging in agonistic behavior can be very costly and thus there

are many examples in nature of animals who achieve dominance in more

passive ways. In some, the dominance status of an individual is clearly

visible, eliminating the need for agonistic behavior. In wintering bird

flocks, white-crowned sparrows

display a unique white plumage; the higher the percentage of the crown

that consists of white feathers, the higher the status of the

individual.

For other animals, the time spent in the group serves as a determinant

of dominance status. Rank may also be acquired from maternal dominance

rank. In rhesus monkeys,

offspring gain dominance status based on the rank of the mother—the

higher ranked the mother, the higher ranked the offspring will be

(Yahner). Similarly, the status of a male Canada goose

is determined by the rank of his family. Although dominance is

determined differently in each case, it is influenced by the

relationships between members of social groups.

Regulation mechanisms

Individuals with greater hierarchical status tend to displace those ranked lower from access to space, to food and to mating opportunities. Thus, individuals with higher social status tend to have greater reproductive success by mating more often and having more resources to invest in the survival of offspring.

Hence, hierarchy serves as an intrinsic factor for population control,

ensuring adequate resources for the dominant individuals and thus

preventing widespread starvation. Territorial behavior enhances this effect.

In eusocial animals

The suppression of reproduction by dominant individuals is the most common mechanism that maintains the hierarchy. In eusocial mammals

this is mainly achieved by aggressive interactions between the

potential reproductive females. In eusocial insects, aggressive

interactions are common determinants of reproductive status, such as in

the bumblebee Bombus bifarius, the paper wasp Polistes annularis and in the ants Dinoponera australis and D. quadriceps.

In general, aggressive interactions are ritualistic and involve

antennation (drumming), abdomen curling and very rarely mandible bouts

and stinging. The winner of the interaction may walk over the

subordinated, that in turn assumes a prostrated posture. To be

effective, these regulatory mechanisms must include traits that make an

individual rank position readily recognizable by its nestmates. The

composition of the lipid layer on the cuticle

of social insects is the clue used by nestmates to recognize each other

in the colony, and to discover each insect's reproductive status (and

rank). Visual cues may also transmit the same information. Paper wasps Polistes dominulus

have individual "facial badges" that permit them to recognize each

other and to identify the status of each individual. Individuals whose

badges were modified by painting were aggressively treated by their

nestmates; this makes advertising a false ranking status costly, and may

help to suppress such advertising.

Other behaviors are involved in maintaining reproductive status in social insects. The removal of a thoracic sclerite in Diacamma

ants inhibits ovary development; the only reproductive individual of

this naturally queenless genus is the one that retains its sclerite

intact. This individual is called a gamergate, and is responsible for mutilating all the newly emerged females, to maintain its social status. Gamergates of Harpegnathos saltator arise from aggressive interactions, forming a hierarchy of potential reproductives.

In the honey bee Apis mellifera, a pheromone produced by the queen mandibular glands is responsible for inhibiting ovary development in the worker caste. "Worker policing" is an additional mechanism that prevents reproduction by workers, found in bees and ants. Policing may involve oophagy and immobilization of workers who lay eggs. In some ant species such as the carpenter ant Camponotus floridanus,

eggs from queens have a peculiar chemical profile that workers can

distinguish from worker laid eggs. When worker-laid eggs are found, they

are eaten. In some species, such as Pachycondyla obscuricornis, workers may try to escape policing by shuffling their eggs within the egg pile laid by the queen.

Hormonal control

Modulation of hormone levels after hibernation may be associated with dominance hierarchies in the social order of the paper wasp (Polistes dominulus).

This depends on the queen (or foundress), possibly involving specific

hormones. Laboratory experiments have shown that when foundresses are

injected with juvenile hormone,

responsible for regulating growth and development in insects including

wasps, the foundresses exhibit an increase in dominance. Further, foundresses with larger corpora allata,

a region of the female wasp brain responsible for the synthesis and

secretion of juvenile hormone, are naturally more dominant.

A follow-up experiment utilized 20-hydroxyecdysone, an ecdysone known to enhance maturation and size of oocytes. The size of the oocytes plays a significant role in establishing dominance in the paper wasp.

Foundresses treated with 20-hydroxyecdysone showed increased dominance

compared to those treated with juvenile hormone, so 20-hydroxyecdysone

may play a larger role in establishing dominance (Roseler et al.,

1984). Subsequent research however, suggests that juvenile hormone is

implicated, though only on certain individuals. When injected with

juvenile hormone, larger foundresses showed more mounting behaviors than

smaller ones, and more oocytes in their ovaries.

Naked mole-rats (Heterocephalus glaber)

similarly have a dominance hierarchy dependent on the highest ranking

female (queen) and her ability to suppress critically important

reproductive hormones in male and female sub-dominants. In sub-dominant

males, it appears that luteinizing hormone and testosterone are suppressed, while in females it appears that the suppression involves the entire suppression of the ovarian cycle. This suppression reduces sexual virility and behavior and thus redirects the sub-dominant's behavior into helping the queen with her offspring, though the mechanisms of how this is accomplished are debated. Former research suggests that primer pheromones

secreted by the queen cause direct suppression of these vital

reproductive hormones and functions however current evidence suggests

that it is not the secretion of pheromones which act to suppress

reproductive function but rather the queen's extremely high levels of

circulating testosterone, which cause her to exert intense dominance and

aggressiveness on the colony and thus "scare" the other mole-rats into submission.

Research has shown that removal of the queen from the colony allows the

reestablishment of reproductive function in sub-dominant individuals.

To see if a priming pheromone secreted by the queen was indeed causing

reproductive suppression, researchers removed the queen from the colony

but did not remove her bedding. They reasoned that if a primer

pheromones were on the bedding then the sub-dominant's reproductive

function should continue to be suppressed. Instead however, they found

that the sub-dominants quickly regained reproductive function even in

the presence of the queen's bedding and thus it was concluded that

primer pheromones do not seem to play a role in suppressing reproductive

function.

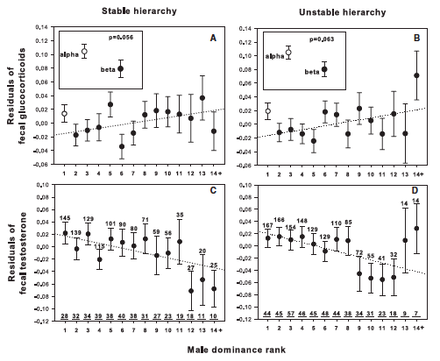

Glucocorticoids, signaling molecules which stimulate the fight or flight response,

may be implicated in dominance hierarchies. Higher ranking individuals

tend to have much higher levels of circulating glucocorticoids than subdominant individuals, the opposite of what had been expected. Two core hypotheses attempt to explain this.

The first suggests that higher ranking individuals exert more energy and thus need higher levels of glucocorticoids to mobilize glycogen for energy use. This is supported by the fact that when food availability is low, cortisol levels increase within the dominant male. The second suggests that elevated stress hormones

are a result of social factors, particularly when the hierarchy is in

transition, perhaps resulting in increased aggression and confrontation.

As a result, the dominant individual fights more and has elevated

glucocorticoids during this period. Field studies of olive baboons in Kenya

seem to support this, as dominant individuals had lower cortisol levels

in a stable hierarchy than did subdominant individuals, but the reverse

was true at unstable times.

Brain pathways and hierarchy

Several

areas of the brain contribute to hierarchical behavior in animals. One

of the areas that has been linked with this behavior is the prefrontal cortex,

a region involved with decision making and social behavior. High social

rank in a hierarchical group of mice has been associated with increased

excitability in the medial prefrontal cortex of pyramidal neurons, the primary excitatory cell type of the brain. High ranking macaques have a larger rostral prefrontal cortex in large social groups. Neuroimaging studies with computer stimulated hierarchal conditions showed increased activity in the ventral and dorsolateral

prefrontal cortex, one processing judgment cues and the other

processing status of an individual. Other studies have determined that

lesions to the prefrontal cortex (when the area is severed to disrupt

functioning to observe its role in behavior) led to deficits in

processing social hierarchy cues, suggesting this area is important in

regulating this information.

Although the prefrontal cortex has been implicated, there are other

downstream targets of the prefrontal cortex that have also been linked

in maintaining this behavior. This includes the amygdala

through lesion studies in rats and primates which led to disruption in

hierarchy, and can affect the individual negatively or positively

depending on the subnuclei that is targeted. Additionally, the dorsal

medial PFC-medial dorsal thalamus connection has been linked with maintenance of rank in mice. Another area that has been associated is the dorsal raphe nucleus, the primary serotonergic

nuclei (a neurotransmitter involved with many behaviors including

reward and learning). In manipulation studies of this region, there were

changes in fighting and affiliative behavior in primates and

crustaceans.

In specific groups

Female dominance in mammals

The

bonobo is one of the few mammals with female-biased dominance.

Female-biased dominance occurs rarely in mammals. It occurs when all

adult males exhibit submissive behavior to adult females in social

settings. These social settings are usually related to feeding,

grooming, and sleeping site priority. It is observed consistently in hyenas, lemurs and the bonobo. The ring-tailed lemur is observed to be the most prominent model of female dominance.

There are three basic proposals for the evolution of female dominance:

- The Energy Conservation Hypothesis: males subordinate to females

to conserve energy for intense male-male competition experienced during

very short breeding seasons

- Female behavioral strategy: dominance helps females deal with the

unusually high reproductive demands; they prevail in more social

conflicts because they have more at stake in terms of fitness.

- Male behavioral strategy: males defer as a parental investment

because it ensures more resources in a harsh unpredictable climate for

the female, and thus, the male's future offspring.

In lemurs, no single hypothesis fully explains female social dominance at this time and all three are likely to play a role. Adult female lemurs have increased concentrations of androgens when they transition from non-breeding to breeding seasons, increasing female aggression.

Androgens are greater in pregnant female lemurs, which suggests that

organizational androgens might influence the developing offspring. Organizational androgens play a role in "explaining female social dominance" in ring-tailed lemurs, as androgens are associated with aggressive behavior in young females.

Females that were "exposed to greater concentrations of maternal

[androstenedione] late in fetal development were less likely to be

aggressed against postnatally, whereas females that were...exposed to

greater concentrations of maternal [testosterone]...were more likely to

receive aggression postnatally." Dominance rank in female chimpanzees is correlated with reproductive success. Although a high rank is an advantage for females, clear linear hierarchies in female chimpanzees have not been detected. In "masculinized" female mammals like the spotted hyena (Crocuta crocuta),

androgens (i.e. specifically, androstenedione and testosterone) are

"implicated in the organization and activation of...nonreproductive

behavioral traits, including aggression, social dominance,

rough-and-tumble play, and scent marking" For aggressively dominant female meerkats (Suricata suricatta), they have "exceptionally high concentrations" of androgens, "particularly during gestation".

Birds

Bottom-rank

chicken showing feather damage from pecking by other hens

The concept of dominance, originally called "pecking order", was described in birds by Thorleif Schjelderup-Ebbe in 1921 under the German terms Hackordnung or Hackliste and introduced into English in 1927. In his 1924 German-language article, he noted that "defense and aggression in the hen is accomplished with the beak".

This emphasis on pecking led many subsequent studies on fowl behaviour

to use it as a primary observation; however, it has been noted that roosters tend to leap and use their claws in conflicts.

Wild and feral chickens form relatively small groups, usually

including no more than 10 to 20 individuals. It has been shown that in

larger groups, which is common in farming, the dominance hierarchy

becomes less stable and aggression increases.

Dominance hierarchies are found in many species of bird. For example, the blue-footed booby

brood of two chicks always has a dominance hierarchy due to the

asynchronous hatching of the eggs. One egg is laid four days before the

other, and incubation starts immediately after laying, so the elder

chick is hatched four days before the younger chick and has a four-day

head start on growth. The elder, stronger chick almost always becomes

the dominant chick. During times of food shortage, the dominant chick

often kills the subordinate chick by either repeatedly pecking or by

ousting the younger chick from the nest. The brood hierarchy makes it

easier for the subordinate chick to die quietly in times of food

scarcity, which provides an efficient system for booby parents to

maximize their investment.

Eusocial insects

In insect societies,

only one to few individuals members of a colony can reproduce, whereas

the other colony members have their reproductive capabilities

suppressed. This conflict over reproduction in some cases results in a

dominance hierarchy. Dominant individuals in this case are known as

queens and have the obvious advantage of performing reproduction and

benefiting from all the tasks performed by their subordinates, the

worker caste (foraging, nest maintenance, nest defense, brood care and

thermal regulation). According to Hamilton's rule,

the reproduction costs of the worker caste are compensated by the

contribution of workers to the queen's reproductive success, with which

they share genes. This is true not only for the popular social insects (ants, termites, some bees and wasps), but also for the naked mole-rat Heterocephalus glaber. In a laboratory experiment, Clarke and Faulkes (1997) demonstrated that reproductive status in a colony of H. glaber

was correlated with the individual's ranking position within a

dominance hierarchy, but aggression between potential reproductives only

started after the queen was removed.

The social insects mentioned above, excluding termites, are haplodiploid. Queen and workers are diploid, but males develop from haploid genotypes. In some species, suppression of ovary development is not totally achieved in the worker caste, which opens the possibility of reproduction by workers. Since nuptial flights are seasonal and workers are wingless, workers are almost always non-breeders, and (as gamergate ants or laying worker bees)

can only lay unfertilised eggs. These eggs are in general viable,

developing into males. A worker that performs reproduction is considered

a "cheater" within the colony, because its success in leaving

descendants becomes disproportionally larger, compared to its sisters

and mother. The advantage of remaining functionally sterile is only

accomplished if every worker assume this "compromise". When one or more

workers start reproducing, the "social contract" is destroyed and the

colony cohesion is dissolved. Aggressive behavior derived from this

conflict may result in the formation of hierarchies, and attempts of

reproduction by workers are actively suppressed. In some wasps, such as Polistes fuscatus,

instead of not laying eggs, the female workers begin being able to

reproduce, but once being under the presence of dominant females, the

subordinate female workers can no longer reproduce.

In some wasp species such as Liostenogaster flavolineata

there are many possible queens that inhabit a nest, but only one can be

queen at a time. When a queen dies the next queen is selected by an

age-based dominance hierarchy. This is also true in the species Polistes instabilis, where the next queen is selected based on age rather than size. Polistes exclamans also exhibits this type of hierarchy. Within the dominance hierarchies of the Polistes versicolor,

however, the dominant-subordinate context in the yellow paper wasps is

directly related to the exchange of food. Future foundresses within the

nest compete over the shared resources of nourishment, such as protein.

Unequal nourishment is often what leads to the size differences that

result in dominant-subordinate position rankings. Therefore, if during

the winter aggregate, the female is able to obtain greater access to

food, the female could thus reach a dominant position.

In some species, especially in ants, more than one queen can be found in the same colony, a condition called polygyny.

In this case, another advantage of maintaining a hierarchy is to

prolong the colony lifespan. The top ranked individuals may die or lose

fertility and "extra queens" may benefit from starting a colony in the

same site or nest. This advantage is critical in some ecological

contexts, such as in situations where nesting sites are limited or

dispersal of individuals is risky due to high rates of predation. This

polygynous behavior has also been observed in some eusocial bees such as

Schwarziana quadripunctata. In this species, multiple queens of varying sizes are present. The larger, physogastric, queens typically control the nest, though a "dwarf" queen will take its place in the case of a premature death.

Variations

Spectrum of social systems

Dominance hierarchies emerge as a result of intersexual and intrasexual

selection within groups, where competition between individuals results

in differential access to resources and mating opportunities. This can

be mapped across a spectrum of social organization ranging from

egalitarian to despotic, varying across multiple dimensions of

cooperation and competition in between.

Conflict can be resolved in multiple ways, including aggression,

tolerance, and avoidance. These are produced by social decision-making,

described in the "relational model" created by the zoologist Frans De Waal.

In systems where competition between and within the sexes is low,

social behaviour gravitates towards tolerance and egalitarianism, such

as that found in woolley spider monkeys. In despotic systems where competition is high, one or two members are

dominant while all other members of the living group are equally

submissive, as seen in Japanese and rhesus macaques, leopard geckos, dwarf hamsters, gorillas, the cichlid Neolamprologus pulcher, and African wild dog.

Linear ranking systems, or "pecking orders", which tend to fall in

between egalitarianism and despotism, follow a structure where every

member of the group is recognized as either dominant or submissive

relative to every other member. This results in a linear distribution of

rank, as seen in spotted hyenas and brown hyenas.

Context dependency

Eringer cattle competing for dominance.

Dominance and its organisation can be highly variable depending on the context or individuals involved. In European badgers,

dominance relationships may vary with time as individuals age, gain or

lose social status, or change their reproductive condition. Dominance may also vary across space in territorial

animals as territory owners are often dominant over all others in their

own territory but submissive elsewhere, or dependent on the resource.

Even with these factors held constant, perfect dominance hierarchies are

rarely found in groups of any great size, at least in the wild.

Dominance hierarchies in small herds of domestic horses are generally

linear hierarchies whereas in large herds the relationships are

triangular. Dominance hierarchies can be formed at a very early age. Domestic piglets are highly precocious

and, within minutes of being born, or sometimes seconds, will attempt

to suckle. The piglets are born with sharp teeth and fight to develop a

teat order as the anterior teats produce a greater quantity of milk. Once established, this teat order remains stable with each piglet tending to feed from a particular teat or group of teats. Dominance–subordination relationships can vary markedly between breeds of the same species. Studies on Merinos and Border Leicesters

sheep revealed an almost linear hierarchy in the Merinos but a less

rigid structure in the Border Leicesters when a competitive feeding

situation was created.

Species with egalitarian/non-linear hierarchies

Although

many group-living animal species have a hierarchy of some form, some

species have more fluid and flexible social groupings, where rank does

not need to be rigidly enforced, and low-ranking group members may enjoy

a wider degree of social flexibility. Some animal societies are

"democratic", with low-ranking group members being able to influence

which group member is leader and which one is not. Sometimes dominant

animals must maintain alliances with subordinates and grant them favours

to receive their support in order to retain their dominant rank. In

chimpanzees, the alpha male may need to tolerate lower-ranking group

members hovering near fertile females or taking portions of his meals.

Other examples can include Muriqui monkeys. Within their groups, there

is abundant food and females will mate promiscuously. Because of this,

males gain very little in fighting over females, who are, in turn, too

large and strong for males to monopolize or control, so males do not

appear to form especially prominent ranks between them, with several

males mating with the same female in view of each other. This type of mating style is also present in manatees, removing their need to engage in serious fighting.

Among female elephants, leadership roles are not acquired by sheer

brute force, but instead through seniority, and other females can

collectively show preferences for where the herd can travel. In hamadryas baboons, several high-ranking males will share a similar rank, with no single male being an absolute leader. Female bats also have a somewhat fluid social structure, in which rank is not strongly enforced.

Bonobos are matriarchal, yet their social groups are also generally

quite flexible, and serious aggression is quite rare between them.

In olive baboons, certain animals are dominant in certain contexts, but

not in others. Prime age male olive baboons claim feeding priority, yet

baboons of any age or sex can initiate and govern the group's

collective movements.