Protectionism, sometimes referred to as trade protectionism, is the economic policy of restricting imports from other countries through methods such as tariffs on imported goods, import quotas, and a variety of other government regulations. Proponents argue that protectionist policies shield the producers, businesses, and workers of the import-competing sector in the country from foreign competitors. Opponents argue that protectionist policies reduce trade and adversely affect consumers in general (by raising the cost of imported goods) as well as the producers and workers in export sectors, both in the country implementing protectionist policies and, in the countries, protected against.

Protectionism is advocated mainly by parties that hold economic nationalist or left-wing positions (although paleoconservatives have also supported the practice), while economically right-wing political parties generally support free trade.

There is a consensus among economists that protectionism has a negative effect on economic growth and economic welfare, while free trade and the reduction of trade barriers have a significantly positive effect on economic growth. Some scholars, such as Douglas Irwin, have implicated protectionism as the cause of some economic crises, most notably the Great Depression. Although trade liberalization can sometimes result in large and unequally distributed losses and gains, and can, in the short run, cause significant economic dislocation of workers in import-competing sectors, free trade has advantages of lowering costs of goods and services for both producers and consumers.

Protectionist policies

A variety of policies have been used to achieve protectionist goals. These include:

- Tariffs and import quotas are the most common types of protectionist policies. A tariff is an excise tax levied on imported goods. Originally imposed to raise government revenue, modern tariffs are now used primarily to protect domestic producers and wage rates from lower-priced importers. An import quota is a limit on the volume of a good that may be legally imported, usually established through an import licensing regime.

- Protection of technologies, patents, technical and scientific knowledge.

- Restrictions on foreign direct investment, such as restrictions on the acquisition of domestic firms by foreign investors.

- Administrative barriers: Countries are sometimes accused of using their various administrative rules (e.g., regarding food safety, environmental standards, electrical safety, etc.) as a way to introduce barriers to imports.

- Anti-dumping legislation: "Dumping" is the practice of firms selling to export markets at lower prices than are charged in domestic markets. Supporters of anti-dumping laws argue that they prevent the import of cheaper foreign goods that would cause local firms to close down. However, in practice, anti-dumping laws are usually used to impose trade tariffs on foreign exporters.

- Direct subsidies: Government subsidies (in the form of lump-sum payments or cheap loans) are sometimes given to local firms that cannot compete well against imports. These subsidies are purported to "protect" local jobs and to help local firms adjust to the world markets.

- Export subsidies: Export subsidies are often used by governments to increase exports. Export subsidies have the opposite effect of export tariffs because exporters get payment, which is a percentage or proportion of the value of exported. Export subsidies increase the amount of trade, and in a country with floating exchange rates, have effects similar to import subsidies.

- Exchange rate control: A government may intervene in the foreign exchange market to lower the value of its currency by selling its currency in the foreign exchange market. Doing so will raise the cost of imports and lower the cost of exports, leading to an improvement in its trade balance. However, such a policy is only effective in the short run, as it will lead to higher inflation in the country in the long run, which will, in turn, raise the real cost of exports, and reduce the relative price of imports.

- International patent systems: There is an argument for viewing national patent systems as a cloak for protectionist trade policies at a national level. Two strands of this argument exist: one when patents held by one country form part of a system of exploitable relative advantage in trade negotiations against another, and a second where adhering to a worldwide system of patents confers "good citizenship" status despite 'de facto protectionism'. Peter Drahos explains that "States realized that patent systems could be used to cloak protectionist strategies. There were also reputational advantages for states to be seen to be sticking to intellectual property systems. One could attend the various revisions of the Paris and Berne conventions, participate in the cosmopolitan moral dialogue about the need to protect the fruits of authorial labor and inventive genius...knowing all the while that one's domestic intellectual property system was a handy protectionist weapon."

- Political campaigns advocating domestic consumption (e.g. the "Buy American" campaign in the United States, which could be seen as an extra-legal promotion of protectionism.)

- Preferential governmental spending, such as the Buy American Act, federal legislation which called upon the United States government to prefer US-made products in its purchases.

In the modern trade arena, many other initiatives besides tariffs have been called protectionist. For example, some commentators, such as Jagdish Bhagwati, see developed countries' efforts in imposing their own labor or environmental standards as protectionism. Also, the imposition of restrictive certification procedures on imports is seen in this light.

Further, others point out that free trade agreements often have protectionist provisions such as intellectual property, copyright, and patent restrictions that benefit large corporations. These provisions restrict trade in music, movies, pharmaceuticals, software, and other manufactured items to high-cost producers with quotas from low-cost producers set to zero.

History

In the 18th century, Adam Smith famously warned against the "interested sophistry" of industry, seeking to gain an advantage at the cost of the consumers. Friedrich List saw Adam Smith's views on free trade as disingenuous, believing that Smith advocated for free trade so that British industry could lock out underdeveloped foreign competition.

Some have argued that no major country has ever successfully industrialized without some form of economic protection. Economic historian Paul Bairoch wrote that "historically, free trade is the exception and protectionism the rule".

According to economic historians Douglas Irwin and Kevin O'Rourke, "shocks that emanate from brief financial crises tend to be transitory and have a little long-run effect on trade policy, whereas those that play out over longer periods (the early 1890s, early 1930s) may give rise to protectionism that is difficult to reverse. Regional wars also produce transitory shocks that have little impact on long-run trade policy, while global wars give rise to extensive government trade restrictions that can be difficult to reverse."

One study shows that sudden shifts in comparative advantage for specific countries have led some countries to become protectionist: "The shift in comparative advantage associated with the opening up of New World frontiers, and the subsequent “grain invasion” of Europe, led to higher agricultural tariffs from the late 1870s onwards, which as we have seen reversed the move toward freer trade that had characterized mid-nineteenth-century Europe. In the decades after World War II, Japan's rapid rise led to trade friction with other countries. Japan's recovery was accompanied by a sharp increase in its exports of certain product categories: cotton textiles in the 1950s, steel in the 1960s, automobiles in the 1970s, and electronics in the 1980s. In each case, the rapid expansion in Japan's exports created difficulties for its trading partners and the use of protectionism as a shock absorber."

In the United States

According to economic historian Douglas Irwin, a common myth about US trade policy is that low tariffs harmed American manufacturers in the early 19th century and then that high tariffs made the United States into a great industrial power in the late 19th century. A review by The Economist of Irwin's 2017 book Clashing over Commerce: A History of US Trade Policy states:

Political dynamics would lead people to see a link between tariffs and the economic cycle that was not there. A boom would generate enough revenue for tariffs to fall, and when the bust came pressure would build to raise them again. By the time that happened, the economy would be recovering, giving the impression that tariff cuts caused the crash and the reverse generated the recovery. 'Mr. Irwin' also attempts to debunk the idea that protectionism made America a great industrial power, a notion believed by some to offer lessons for developing countries today. As its share of global manufacturing powered from 23% in 1870 to 36% in 1913, the admittedly high tariffs of the time came with a cost, estimated at around 0.5% of GDP in the mid-1870s. In some industries, they might have sped up development by a few years. But American growth during its protectionist period was more to do with its abundant resources and openness to people and ideas.

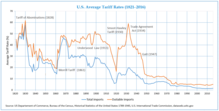

According to Irwin, tariffs have serve three primary purposes in the United States: "to raise revenue for the government, to restrict imports and protect domestic producers from foreign competition, and to reach reciprocity agreements that reduce trade barriers." From 1790 to 1860, average tariffs increased from 20 percent to 60 percent before declining again to 20 percent. From 1861 to 1933, which Irwin characterizes as the "restriction period", the average tariffs increased to 50 percent and remained at that level for several decades. From 1934 onwards, which Irwin characterizes as the "reciprocity period", the average tariff declined substantially until it leveled off at 5 percent.

Economist Paul Bairoch documented that the United States imposed among the highest rates in the world from around the founding of the country until the World War II period, describing the United States as "the mother country and bastion of modern protectionism" since the end of the 18th century and until the post-World War II period. Alexander Hamilton, the first United States Secretary of the Treasury, was of the view, as articulated most famously in his "Report on Manufactures", that developing an industrialized economy was impossible without protectionism because import duties are necessary to shelter domestic "infant industries" until they could achieve economies of scale. The industrial takeoff of the United States occurred under protectionist policies 1816–1848 and under moderate protectionism 1846–1861, and continued under strict protectionist policies 1861–1945. In the late 19th century, higher tariffs were introduced on the grounds that they were needed to protect American wages and to protect American farmers. Between 1824 and the 1940s, the U.S. imposed much higher average tariff rates on manufactured products than did Britain or any other European country, with the exception for a period of time of Spain and Russia. Up until the end of World War II, the United States had the most protectionist economy on Earth.

The Bush administration implemented tariffs on Chinese steel in 2002; according to a 2005 review of existing research on the tariff, all studies found that the tariffs caused more harm than gains to the US economy and employment. The Obama administration implemented tariffs on Chinese tires between 2009 and 2012 as an anti-dumping measure; a 2016 study found that these tariffs had no impact on employment and wages in the US tire industry.

In 2018, EU Trade Commissioner Cecilia Malmström stated that the US was "playing a dangerous game" in applying tariffs on steel and aluminum imports from most countries and stated that she saw the Trump administration's decision to do so as both "pure protectionist" and "illegal".

The tariffs imposed by the Trump administration during the China-United States trade war led to a reduction in the United States trade deficit with China.

In Europe

Europe became increasingly protectionist during the eighteenth century. Economic historians Findlay and O'Rourke write that in "the immediate aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, European trade policies were almost universally protectionist," with the exceptions being smaller countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark.

Europe increasingly liberalized its trade during the 19th century. Countries such as Britain, the Netherlands, Denmark, Portugal and Switzerland, and arguably Sweden and Belgium, had fully moved towards free trade prior to 1860. Economic historians see the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 as the decisive shift toward free trade in Britain. A 1990 study by the Harvard economic historian Jeffrey Williamson showed that the Corn Laws (which imposed restrictions and tariffs on imported grain) substantially increased the cost of living for British workers, and hampered the British manufacturing sector by reducing the disposable incomes that British workers could have spent on manufactured goods. The shift towards liberalization in Britain occurred in part due to "the influence of economists like David Ricardo", but also due to "the growing power of urban interests".

Findlay and O'Rourke characterize 1860 Cobden Chevalier treaty between France and the United Kingdom as "a decisive shift toward European free trade." This treaty was followed by numerous free trade agreements: "France and Belgium signed a treaty in 1861; a Franco-Prussian treaty was signed in 1862; Italy entered the “network of Cobden-Chevalier treaties” in 1863 (Bairoch 1989, 40); Switzerland in 1864; Sweden, Norway, Spain, the Netherlands, and the Hanseatic towns in 1865; and Austria in 1866. By 1877, less than two decades after the Cobden Chevalier treaty and three decades after British Repeal, Germany “had virtually become a free trade country” (Bairoch, 41). Average duties on manufactured products had declined to 9–12% on the Continent, a far cry from the 50% British tariffs, and numerous prohibitions elsewhere, of the immediate post-Waterloo era (Bairoch, table 3, p. 6, and table 5, p. 42)."

Some European powers did not liberalize during the 19th century, such as the Russian Empire and Austro-Hungarian Empire which remained highly protectionist. The Ottoman Empire also became increasingly protectionist. In the Ottoman Empire's case, however, it previously had liberal free trade policies during the 18th to early 19th centuries, which British prime minister Benjamin Disraeli cited as "an instance of the injury done by unrestrained competition" in the 1846 Corn Laws debate, arguing that it destroyed what had been "some of the finest manufacturers of the world" in 1812.

The countries of Western Europe began to steadily liberalize their economies after World War II and the protectionism of the interwar period.

In Canada

Since 1971 Canada has protected producers of eggs, milk, cheese, chicken, and turkey with a system of supply management. Though prices for these foods in Canada exceed global prices, the farmers and processors have had the security of a stable market to finance their operations. Doubts about the safety of bovine growth hormone, sometimes used to boost dairy production, led to hearings before the Senate of Canada, resulting in a ban in Canada. Thus, supply management of milk products is consumer protection of Canadians.

In Latin America

Most Latin American Countries became independent in the early 19th century. They revolted against their colonizers (primarily Spain, France, and Portugal) and set off on their own. Following the achievement of their independence, most of the Latin American countries adopted protectionism. They both feared that any foreign competition would stomp out their newly created state and figured that lack of outside resources would drive domestic production.

Another reason for protectionism was that Latin America was frequently attacked by outsiders. Spain, the United States of America, France, and Texas had all invaded or attempted to invade Latin America by the year 1880. It could be said that Latin America was essentially hiding in its shell trying just to survive in the 19th century.

Yet the protectionist behavior continued up until and during the World Wars. No Latin American countries got seriously involved with either side. Rather, they just kept harvesting their crops (mostly fruits, tobacco, and sugar) and increasing their exports under an ever-growing tariff rate. During World War 2, Latin America had, on average, the highest tariffs in the world.

There was a slight decrease in Latin American tariffs after World War 2, when Asia started to become very protectionist in order to rebuild yet the Latin Americans were still there. To this day, there are countries that only trade freely with other Latin American countries.

Impact

There is a broad consensus among economists that protectionism has a negative effect on economic growth and economic welfare, while free trade and the reduction of trade barriers has a positive effect on economic growth.

Protectionism is frequently criticized by economists as harming the people it is meant to help. Mainstream economists instead support free trade. The principle of comparative advantage shows that the gains from free trade outweigh any losses as free trade creates more jobs than it destroys because it allows countries to specialize in the production of goods and services in which they have a comparative advantage. Protectionism results in deadweight loss; this loss to overall welfare gives no-one any benefit, unlike in a free market, where there is no such total loss. According to economist Stephen P. Magee, the benefits of free trade outweigh the losses by as much as 100 to 1.

Living standards

A 2016 study found that "trade typically favors the poor", as they spend a greater share of their earnings on goods, as free trade reduces the costs of goods. Other research found that China's entry to the WTO benefitted US consumers, as the price of Chinese goods were substantially reduced. Harvard economist Dani Rodrik argues that while globalization and free trade does contribute to social problems, "a serious retreat into protectionism would hurt the many groups that benefit from trade and would result in the same kind of social conflicts that globalization itself generates. We have to recognize that erecting trade barriers will help in only a limited set of circumstances and that trade policy will rarely be the best response to the problems [of globalization]".

Growth

According to economic historians Findlay and O'Rourke, there is a consensus in the economics literature that protectionist policies in the interwar period "hurt the world economy overall, although there is a debate about whether the effect was large or small."

Economic historian Paul Bairoch argued that economic protection was positively correlated with economic and industrial growth during the 19th century. For example, GNP growth during Europe's "liberal period" in the middle of the century (where tariffs were at their lowest), averaged 1.7% per year, while industrial growth averaged 1.8% per year. However, during the protectionist era of the 1870s and 1890s, GNP growth averaged 2.6% per year, while industrial output grew at 3.8% per year, roughly twice as fast as it had during the liberal era of low tariffs and free trade. One study found that tariffs imposed on manufactured goods increase economic growth in developing countries, and this growth impact remains even after the tariffs are repealed. However, another study examining the tariff variation across the Australian colonies prior to Federation did not find any association between tariffs and growth.

According to Dartmouth economist Douglas Irwin, "that there is a correlation between high tariffs and growth in the late nineteenth century cannot be denied. But correlation is not causation... there is no reason for necessarily thinking that import protection was a good policy just because the economic outcome was good: the outcome could have been driven by factors completely unrelated to the tariff, or perhaps could have been even better in the absence of protection." Irwin furthermore writes that "few observers have argued outright that the high tariffs caused such growth."

According to Oxford economic historian Kevin O'Rourke, "It seems clear that protection was important for the growth of US manufacturing in the first half of the 19th century; but this does not necessarily imply that the tariff was beneficial for GDP growth. Protectionists have often pointed to German and American industrialization during this period as evidence in favor of their position, but economic growth is influenced by many factors other than trade policy, and it is important to control for these when assessing the links between tariffs and growth."

A prominent 1999 study by Jeffrey A. Frankel and David H. Romer found, contrary to free trade skeptics' claims, while controlling for relevant factors, that trade does indeed have a positive impact on growth and incomes.

Economist Arvind Panagariya criticizes the view that protectionism is good for growth. Such arguments, according to him, arise from "revisionist interpretation" of East Asian "tigers"' economic history. The Asian tigers achieved a rapid increase in per capita income without any "redistributive social programs", through free trade, which advanced Western economies took a century to achieve.

Developing world

There is broad consensus among economists that free trade helps workers in developing countries, even though they are not subject to the stringent health and labor standards of developed countries. This is because "the growth of manufacturing—and of the myriad other jobs that the new export sector creates—has a ripple effect throughout the economy" that creates competition among producers, lifting wages and living conditions. The Nobel laureates, Milton Friedman and Paul Krugman, have argued for free trade as a model for economic development. Alan Greenspan, former chair of the American Federal Reserve, has criticized protectionist proposals as leading "to an atrophy of our competitive ability. ... If the protectionist route is followed, newer, more efficient industries will have less scope to expand, and overall output and economic welfare will suffer."

Protectionists postulate that new industries may require protection from entrenched foreign competition in order to develop. Mainstream economists do concede that tariffs can in the short-term help domestic industries to develop but are contingent on the short-term nature of the protective tariffs and the ability of the government to pick the winners. The problems are that protective tariffs will not be reduced after the infant industry reaches a foothold, and that governments will not pick industries that are likely to succeed. Economists have identified a number of cases across different countries and industries where attempts to shelter infant industries failed.

Economists such as Paul Krugman have speculated that those who support protectionism ostensibly to further the interests of workers in the least developed countries are in fact being disingenuous, seeking only to protect jobs in developed countries. Additionally, workers in the least developed countries only accept jobs if they are the best on offer, as all mutually consensual exchanges must be of benefit to both sides, or else they wouldn't be entered into freely. That they accept low-paying jobs from companies in developed countries shows that their other employment prospects are worse. A letter reprinted in the May 2010 edition of Econ Journal Watch identifies a similar sentiment against protectionism from 16 British economists at the beginning of the 20th century.

Conflict

Protectionism has also been accused of being one of the major causes of war. Proponents of this theory point to the constant warfare in the 17th and 18th centuries among European countries whose governments were predominantly mercantilist and protectionist, the American Revolution, which came about ostensibly due to British tariffs and taxes, as well as the protective policies preceding both World War I and World War II. According to a slogan of Frédéric Bastiat (1801–1850), "When goods cannot cross borders, armies will."

Current world trends

Certain policies of First World governments have been criticized as protectionist, however, such as the Common Agricultural Policy in the European Union, longstanding agricultural subsidies and proposed "Buy American" provisions in economic recovery packages in the United States.

Heads of the G20 meeting in London on 2 April 2009 pledged "We will not repeat the historic mistakes of protectionism of previous eras". Adherence to this pledge is monitored by the Global Trade Alert, providing up-to-date information and informed commentary to help ensure that the G20 pledge is met by maintaining confidence in the world trading system, deterring beggar-thy-neighbor acts and preserving the contribution that exports could play in the future recovery of the world economy.

Although they were reiterating what they had already committed to, last November in Washington, 17 of these 20 countries were reported by the World Bank as having imposed trade restrictive measures since then. In its report, the World Bank says most of the world's major economies are resorting to protectionist measures as the global economic slowdown begins to bite. Economists who have examined the impact of new trade-restrictive measures using detailed bilaterally monthly trade statistics estimated that new measures taken through late 2009 were distorting global merchandise trade by 0.25% to 0.5% (about $50 billion a year).

Since then, however, President Donald Trump announced in January 2017 the U.S. was abandoning the TPP (Trans-Pacific Partnership) deal, saying, “We’re going to stop the ridiculous trade deals that have taken everybody out of our country and taken companies out of our country, and it’s going to be reversed.”