The eradication of infectious diseases is the reduction of the prevalence of an infectious disease in the global host population to zero.

Two infectious diseases have successfully been eradicated: smallpox in humans, and rinderpest in ruminants. There are four ongoing programs, targeting the human diseases poliomyelitis (polio), yaws, dracunculiasis (Guinea worm), and malaria. Five more infectious diseases have been identified as of April 2008 as potentially eradicable with current technology by the Carter Center International Task Force for Disease Eradication — measles, mumps, rubella, lymphatic filariasis (elephantiasis) and cysticercosis (pork tapeworm).

The concept of disease eradication is sometimes confused with disease elimination, which is the reduction of an infectious disease's prevalence in a regional population to zero, or the reduction of the global prevalence to a negligible amount. Further confusion arises from the use of the term 'eradication' to refer to the total removal of a given pathogen from an individual (also known as clearance of an infection), particularly in the context of HIV and certain other viruses where such cures are sought.

The targeting of infectious diseases for eradication is based on narrow criteria, as both biological and technical features determine whether a pathogenic organism is (at least potentially) eradicable. The targeted pathogen must not have a significant non-human (or non-human-dependent) reservoir (or, in the case of animal diseases, the infection reservoir must be an easily identifiable species, as in the case of rinderpest). This requires sufficient understanding of the life cycle and transmission of the pathogen. An efficient and practical intervention (such as a vaccine or antibiotic) must be available to interrupt transmission. Studies of measles in the pre-vaccination era led to the concept of the critical community size, the minimal size of the population below which a pathogen ceases to circulate. The use of vaccination programs before the introduction of an eradication campaign can reduce the susceptible population. The disease to be eradicated should be clearly identifiable, and an accurate diagnostic tool should exist. Economic considerations, as well as societal and political support and commitment, are other crucial factors that determine eradication feasibility.

Eradicated diseases

So far, only two diseases have been successfully eradicated—one specifically affecting humans (smallpox) and one affecting cattle (rinderpest).

Smallpox

Smallpox is the first disease, and so far the only infectious disease of humans, to be eradicated by deliberate intervention. It became the first disease for which there was an effective vaccine in 1798 when Edward Jenner showed the protective effect of inoculation (vaccination) of humans with material from cowpox lesions.

Smallpox (variola) occurred in two clinical varieties: variola major, with a mortality rate of up to 40 percent, and variola minor, also known as alastrim, with a mortality rate of less than one percent. The last naturally occurring case of variola major was diagnosed in October 1975 in Bangladesh. The last naturally occurring case of smallpox (variola minor) was diagnosed on 26 October 1977, in Ali Maow Maalin, in the Merca District, of Somalia. The source of this case was an outbreak in the nearby district of Kurtunwarey. All 211 contacts were traced, revaccinated, and kept under surveillance.

After two years' detailed analysis of national records, the global eradication of smallpox was certified by an international commission of smallpox clinicians and medical scientists on 9 December 1979, and endorsed by the General Assembly of the World Health Organization on 8 May 1980. However, there is an ongoing debate regarding the continued storage of the smallpox virus by labs in the US and Russia, as any accidental or deliberate release could create a new epidemic in people born since the late 1980s due to the cessation of vaccinations against the smallpox virus.

Rinderpest

During the twentieth century, there were a series of campaigns to eradicate rinderpest, a viral disease that infected cattle and other ruminants and belonged to the same family as measles, primarily through the use of a live attenuated vaccine. The final, successful campaign was led by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. On 14 October 2010, with no diagnoses for nine years, the FAO announced that the disease had been completely eradicated, making this the first (and so far the only) disease of livestock to have been eradicated by human undertakings.

Global eradication underway

Poliomyelitis (polio)

| Year | Estimated | Recorded |

|---|---|---|

| 1975 | — | 49,293 |

| 1980 | 400,000 | 52,552 |

| 1985 | — | 38,637 |

| 1988 | 350,000 | 35,251 |

| 1990 | — | 23,484 |

| 1993 | 100,000 | 10,487 |

| 1995 | — | 7,035 |

| 2000 | — | 2,971 |

| 2005 | — | 1,998 |

| 2010 | — | 1,352 |

| 2011 | — | 650 |

| 2012 | — | 222 |

| 2013 | — | 385 |

| 2014 | — | 359 |

| 2015 | — | 74 |

| 2016 | — | 37 |

| 2017 | — | 22 |

| 2018 | — | 33 |

| 2019 | — | 176 |

| 2020 | — | 140 |

| 2021 | — | 6 |

| 2022 | — | 30 |

| 2023 | — | 12 |

A dramatic reduction of the incidence of poliomyelitis in industrialized countries followed the development of a vaccine in the 1950s. In 1960, Czechoslovakia became the first country certified to have eliminated polio.

In 1988, the World Health Organization (WHO), Rotary International, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), and the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) passed the Global Polio Eradication Initiative. Its goal was to eradicate polio by the year 2000. The updated strategic plan for 2004–2008 expects to achieve global eradication by interrupting poliovirus transmission, using the strategies of routine immunization, supplementary immunization campaigns, and surveillance of possible outbreaks. The WHO estimates that global savings from eradication, due to forgone treatment and disability costs, could exceed one billion U.S. dollars per year.

The following world regions have been declared polio-free:

- The Americas (1994)

- Western Pacific region, including China (2000)

- Europe (2002)

- Southeast Asia region (2014), including India

- Africa (2020)

The lowest annual wild polio prevalence seen so far was in 2017, with only 22 reported cases, although there were more total reported cases (including circulated vaccine-derived cases) than in 2016, mainly due to reporting of circulated vaccine-derived cases in Syria, where it likely had already been circulating, but gone unreported, presumably due to the civil war. Only two or three countries remain in which poliovirus transmission may never have been interrupted: Pakistan, Afghanistan, and maybe Nigeria. (There have been no cases caused by wild strains of poliovirus in Nigeria since August 2016, though cVDPV2 was detected in environmental samples in 2017.) Nigeria was removed from the WHO list of polio-endemic countries in September 2015 but added back in 2016, and India was removed in 2014 after no new cases were reported for one year.

On 20 September 2015, the World Health Organization announced that wild poliovirus type 2 had been eradicated worldwide, as it has not been seen since 1999. On 24 October 2019, the World Health Organization announced that wild poliovirus type 3 had also been eradicated worldwide. This leaves only wild poliovirus type 1 and vaccine-derived polio circulating in a few isolated pockets, with all wild polio cases after August 2016 in Afghanistan and Pakistan.

Dracunculiasis

| Year | Reported cases | Countries |

|---|---|---|

| 1989 | 892,055 | 16 |

| 1995 | 129,852 | 19 |

| 2000 | 75,223 | 16 |

| 2005 | 10,674 | 12 |

| 2010 | 1,797 | 6 |

| 2011 | 1,060 | 4 |

| 2012 | 542 | 4 |

| 2013 | 148 | 5 |

| 2014 | 126 | 4 |

| 2015 | 22 | 4 |

| 2016 | 25 | 3 |

| 2017 | 30 | 2 |

| 2018 | 28 | 3 |

| 2019 | 54 | 4 |

| 2020 | 27 | 6 |

| 2021 | 15 | 4 |

| 2022 | 12 | 3 |

Dracunculiasis, also called Guinea worm disease, is a painful and disabling parasitic disease caused by the nematode Dracunculus medinensis. It is spread through consumption of drinking water infested with copepods hosting Dracunculus larvae. The Carter Center has led the effort to eradicate the disease, along with the CDC, the WHO, UNICEF, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Unlike diseases such as smallpox and polio, there is no vaccine or drug therapy for guinea worm. Eradication efforts have been based on making drinking water supplies safer (e.g. by provision of borehole wells, or through treating the water with larvicide), on containment of infection and on education for safe drinking water practices. These strategies have produced many successes: two decades of eradication efforts have reduced Guinea worm's global incidence dramatically from over 100,000 in 1995 to less than 100 cases since 2015. While success has been slower than was hoped (the original goal for eradication was 1995), the WHO has certified 180 countries free of the disease, and in 2020 six countries—South Sudan, Ethiopia, Mali, Angola, Cameroon and Chad—reported cases of guinea worm. As of 2010, the WHO predicted it would be "a few years yet" before eradication is achieved, on the basis that it took 6–12 years for the countries that have so far eliminated guinea worm transmission to do so after reporting a similar number of cases to that reported by Sudan in 2009. Nonetheless, the last 1% of the effort may be the hardest, with cases not substantially decreasing from 2015 (22) to 2020 (24). As a result of missing the 2020 target, the WHO has revised its target for eradication to 2030. The worm is now understood to be able to infect dogs, domestic cats and baboons as well as humans, providing a natural reservoir for the pathogen and thus complicating eradication efforts. In response, the eradication effort is now also targeting animals (especially wild dogs) for treatment and isolation since animal infections far outnumber human infections now (in 2020 Chad reported 1570 animal infections and 12 human infections).

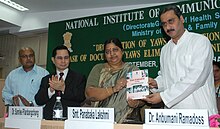

Yaws

Yaws is a rarely fatal but highly disfiguring disease caused by the spiral-shaped bacterium (spirochete) Treponema pallidum pertenue, a close relative of the syphilis bacterium Treponema pallidum pallidum, spread through skin to skin contact with infectious lesions. The global prevalence of this disease and the other endemic treponematoses, bejel and pinta, was reduced by the Global Control of Treponematoses programme between 1952 and 1964 from about 50 million cases to about 2.5 million (a 95% reduction). However, following the cessation of this program these diseases remained at a low prevalence in parts of Asia, Africa and the Americas with sporadic outbreaks. In 2012, the WHO targeted the disease for eradication by 2020, a goal that was missed.

As of 2020, there were 15 countries known to be endemic for yaws, with the recent discovery of endemic transmission in Liberia and the Philippines. In 2020, 82,564 cases of yaws were reported to the WHO and 153 cases were confirmed. The majority of the cases are reported from Papua New Guinea and with over 80% of all cases coming from one of three countries in the 2010-2013 period: Papua New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Ghana. A WHO meeting report in 2018 estimated the total cost of elimination to be US$175 million (excluding Indonesia). In the South-East Asian Regional Office of the WHO, the eradication efforts are focused on the remaining endemic countries in this region (Indonesia and East Timor) after India was declared free of yaws in 2016.

The discovery that oral antibiotic azithromycin can be used instead of the previous standard, injected penicillin, was tested on Lihir Island from 2013 to 2014; a single oral dose of the macrolide antibiotic reduced disease prevalence from 2.4% to 0.3% at 12 months. The WHO now recommends both treatment courses (oral azithromycin and injected penicillin), with oral azithromycin being the preferred treatment.

Malaria

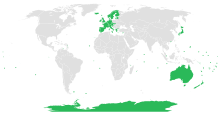

Malaria has been eliminated from most of Europe, North America, Australia, North Africa and the Caribbean, and parts of South America, Asia and Southern Africa. The WHO defines "elimination" (or "malaria free") as having no domestic transmission (indigenous cases) for the past three years. They also define "pre-elimination" and "elimination" stages when a country has fewer than 5 or 1, respectively, cases per 1000 people at risk per year.

In 1955, WHO launched the Global Malaria Eradication Program. Support waned, and the program was suspended in 1969. Since 2000, support for eradication has increased, although some actors in the global health community (including voices within the WHO) thought that eradication as goal was premature and that setting strict deadlines for eradication may be counterproductive as they are likely to be missed.

According to the WHO's World Malaria Report 2015, the global mortality rate for malaria fell by 60% between 2000 and 2015. The WHO targeted a further 90% reduction between 2015 and 2030, with a 40% reduction and eradication in 10 countries by 2020. However, the 2020 goal was missed with a slight increase in cases compared to 2015.

While 31 out of 92 endemic countries were estimated to be on track with the WHO goals for 2020, 15 countries reported an increase of 40% or more between 2015 and 2020. Between 2000 and 30 June 2021, twelve countries were certified by the WHO as being malaria-free. Argentina and Algeria were declared free of malaria in 2019. El Salvador and China were declared malaria free in the first half of 2021.

Regional disparities were evident: Southeast Asia was on track to meet WHO's 2020 goals, while Africa, Americas, Eastern Mediterranean and West Pacific regions were off-track. The six Greater Mekong Subregion countries aim for elimination of P. falciparum transmitted malaria by 2025 and elimination of all malaria by 2030, having achieved a 97% and 90% reduction of cases respectively since 2000. Ahead of World Malaria Day, 25 April 2021, WHO named 25 countries in which it is working to eliminate malaria by 2025 as part of its E-2025 initiative.

A major challenge to malaria elimination is the persistence of malaria in border regions, making international cooperation crucial.

Lymphatic filariasis

Lymphatic filariasis is an infection of the lymph system by mosquito-borne microfilarial worms which can cause elephantiasis. Studies have demonstrated that transmission of the infection can be broken when a single dose of combined oral medicines is consistently maintained annually for approximately seven years. The strategy for eliminating transmission of lymphatic filariasis is mass distribution of medicines that kill the microfilariae and stop transmission of the parasite by mosquitoes in endemic communities. In sub-Saharan Africa, albendazole is being used with ivermectin to treat the disease, whereas elsewhere in the world albendazole is used with diethylcarbamazine. Using a combination of treatments better reduces the number of microfilariae in blood. Avoiding mosquito bites, such as by using insecticide-treated mosquito bed nets, also reduces the transmission of lymphatic filariasis. In the Americas, 95% of the burden of lymphatic filariasis is on the island of Hispaniola (comprising Haiti and the Dominican Republic). An elimination effort to address this is currently under way alongside the malaria effort described above; both countries intend to eliminate the disease by 2020.

As of October 2008, the efforts of the Global Programme to Eliminate LF are estimated to have already prevented 6.6 million new filariasis cases from developing in children, and to have stopped the progression of the disease in another 9.5 million people who have already contracted it. Overall, of 83 endemic countries, mass treatment has been rolled out in 48, and elimination of transmission reportedly achieved in 21.

Regional elimination established or underway

Some diseases have already been eliminated from large regions of the world, and/or are currently being targeted for regional elimination. This is sometimes described as "eradication", although technically the term only applies when this is achieved on a global scale. Even after regional elimination is successful, interventions often need to continue to prevent a disease becoming re-established. Three of the diseases here listed (lymphatic filariasis, measles, and rubella) are among the diseases believed to be potentially eradicable by the International Task Force for Disease Eradication, and if successful, regional elimination programs may yet prove a stepping stone to later global eradication programs. This section does not cover elimination where it is used to mean control programs sufficiently tight to reduce the burden of an infectious disease or other health problem to a level where they may be deemed to have little impact on public health, such as the leprosy, neonatal tetanus, or obstetric fistula campaigns.

Other worm infections

Other than Dracunculiasis and lymphatic filariasis, there is no global commitment to eliminate helminthiasis (worm infections); however, the London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases and the WHO aim to control worm infections, including schistosomiasis and soil-transmitted helminthiasis (which are caused by roundworms, whipworms and hookworms). It is estimated that between 576 and 740 million individuals are infected with hookworm. Of these infected individuals, about 80 million are severely affected.

Soil-transmitted helminthiasis

The current WHO goals are to control soil-transmitted helminthiasis (STH) by 2020 to a point where it does not pose a serious public health problem any more in children and 75% of children have received deworming interventions. By 2018, an average of 60% of school children were reached, however only 16 countries reached more than 75% coverage of pre-school children and 28 countries reached over 75% coverage of school-age children. In 2018, the number of countries with endemic STH was estimated to be 96 (down from 112 in 2010). Sizeable donations of a total of 3.3 billion deworming tablets by GlaxoSmithKline and Johnson & Johnson since 2010 to the WHO allowed progress on its goals. In 2019, the WHO targets were updated to eliminate morbidity of STH by 2030, with less than 2% of all children being infected by that date in all 98 currently endemic countries.

Schistosomiasis

The WHO set a goal to control morbidity of schistosomiasis by 2020 and eliminate the public health problems associated with it by 2025 (bringing infections down to less than 1% of the population). The effort is assisted by the Schistosomiasis Control Initiative. In 2018, a total of 63% of all school age children were treated.

Hookworm

In North American countries, such as the United States, elimination of hookworm had been attained due to scientific advances. Despite the United States declaring that it had eliminated hookworm decades ago, a 2017 study showed it was present in Lowndes County, Alabama. The Rockefeller Foundation's hookworm campaign in the 1920s was supposed to focus on the eradication of hookworm infections for those living in Mexico and other rural areas. However, the campaign was politically influenced, causing it to be less successful, and regions such as Mexico still deal with these infections from parasitic worms. This use of health campaigns by political leaders for political and economic advantages has been termed the science-politics paradox.

Measles

As of 2018, all six WHO regions have goals to eliminate measles, and at the 63rd World Health Assembly in May 2010, delegates agreed to move towards eventual eradication, although no specific global target date has yet been agreed. The Americas set a goal in 1994 to eliminate measles and rubella transmission by 2000, and successfully achieved to reduce cases from over 250,000 in 1990 to only 105 cases in 2003. However, while eradication in the Americas was certified in 2015, the certification was lost in 2018 due to endemic measles transmission in Venezuela and subsequent spread to Brazil and Colombia; while additional limited outbreaks have occurred elsewhere as well. Europe had set a goal to eliminate measles transmission by 2010, which was missed due to the MMR vaccine controversy and by low uptake in certain groups, and despite achieving low levels by 2008, European countries have since experienced a small resurgence in cases. The Eastern Mediterranean also had goals to eliminate measles by 2010 (later revised to 2015), the Western Pacific aims to eliminate the disease by 2012, and in 2009 the regional committee for Africa agreed a goal of measles elimination by 2020. In 2019, the WHO South-East Asian region has set a target to eliminate measles by 2023. As of September 2019, a total of 82 countries were certified to have eliminated endemic measle transmission.

In 2005, a global target was agreed for a 90% reduction in measles deaths by 2010 from the 757,000 deaths in 2000 (later updated to 95% by 2015). Estimates in 2008 showed a 78% decline to 164,000 deaths, further declining to 145,700 in 2013. however, progress has since stalled since and both the 2010 and 2015 target were missed: in 2018, still over 140,000 deaths were reported. As of 2018, global vaccination efforts have reached 86% coverage of the first dose of the measles vaccine and 68% coverage of the second dose.[]

The WHO region of the Americas declared on 27 September 2016 it had eliminated measles. The last confirmed endemic case of measles in the Americas was in Brazil in July 2015. May 2017 saw a return of measles to the US after an outbreak in Minnesota among unvaccinated children. Another outbreak occurred in the state of New York between 2018 and 2019, causing over 200 confirmed measles cases in mostly ultra-Orthodox Jewish communities. Subsequent outbreaks occurred in New Jersey and Washington state with over 30 cases reported in the Pacific Northwest.

The WHO European region missed its elimination target of 2010 as well as the new target of 2015 despite overall coverage of 90% of the first dose of the measles vaccine. In 2018, 84,000 cases were reported in the European region (an increase from 25,000 in 2017); with the majority of cases originating from Ukraine.

By the end of 2021, WHO's European regional office considered the endemic measles eliminated in 33 out of 53 member states, with the transmission interrupted in one more and re-established in five others.

Rubella

Four out of six WHO regions have goals to eliminate rubella, with the WHO recommending using existing measles programmes for vaccination with combined vaccines such as the MMR vaccine. The number of reported cases dropped from 670,000 in the year 2000 to below 15,000 in 2018, and the global coverage of rubella vaccination was estimated at 69% in 2018 by the WHO. The WHO region of the Americas declared on 29 April 2015 it had eliminated rubella and congenital rubella syndrome. The last confirmed endemic case of rubella in the Americas was in Argentina in February 2009. Australia achieved eradication in 2018. As of September 2019, 82 countries were certified to have eliminated rubella.

The WHO European region missed its elimination target of 2010 as well as the new target of 2015 due to undervaccination in Central and Western Europe. As of 2018, 39 countries out of 53 European countries have eliminated endemic Rubella and three additional ones that have interrupted transmission; a total of 850 confirmed rubella cases were reported in the European region in 2018 with 438 of these in Poland. European countries with endemic Rubella in 2018 were: Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Turkey and Ukraine. The disease remains problematic in other regions as well; the WHO regions of Africa and South-East Asia have the highest rates of congenital rubella syndrome and a 2013 outbreak of rubella in Japan resulted in 15,000 cases.

Onchocerciasis

Onchocerciasis (river blindness) is the world's second leading cause of infectious blindness. It is caused by the nematode Onchocerca volvulus, which is transmitted to people via the bite of a black fly. The current WHO goal is to increase the number of countries free of transmission from 4 (in 2020) to 12 in 2030. Elimination of this disease is under way in the region of the Americas, where this disease was endemic to Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico and Venezuela. The principal tool being used is mass ivermectin treatment. If successful, the only remaining endemic locations would be in Africa and Yemen. In Africa, it is estimated that greater than 102 million people in 19 countries are at high risk of onchocerciasis infection, and in 2008, 56.7 million people in 15 of these countries received community-directed treatment with ivermectin. Since adopting such treatment measures in 1997, the African Programme for Onchocerciasis Control reports a reduction in the prevalence of onchocerciasis in the countries under its mandate from a pre-intervention level of 46.5% in 1995 to 28.5% in 2008. Some African countries, such as Uganda, are also attempting elimination and successful elimination was reported in 2009 from two endemic foci in Mali and Senegal.

On 29 July 2013, the Pan American Health Organization (PAHO) announced that after 16 years of efforts, Colombia had become the first country in the world to eliminate the parasitic disease onchocerciasis. It has also been eliminated in Ecuador (2014), Mexico (2015), and Guatemala (2016). The only remaining countries in America in which the disease is endemic are Brazil and Venezuela as of 2021.

Prion diseases

Following an epidemic of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease in the UK in the 1990s, there have been campaigns to eliminate bovine spongiform encephalopathy in cattle across the European Union and beyond which have achieved large reductions in the number of cattle with this disease. Cases of variant Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease have also fallen since then, from an annual peak of 29 cases in 2000 to five in 2008 and none in 2012. Two cases were reported in both 2013 and 2014: two in France; one in the United Kingdom and one in the United States.

Following the ongoing eradication effort, only seven cases of bovine spongiform encephalopathy were reported worldwide in 2013: three in the United Kingdom, two in France, one in Ireland and one in Poland. This is the lowest number of cases since at least 1988. In 2015, there were at least six reported cases (three of the atypical H-type). Four cases were reported globally in 2017, and the condition is considered to be nearly eradicated.

With the cessation of cannibalism among the Fore people, the last known victims of kuru died in 2005 or 2009, but the disease has a very long incubation period.

Syphilis

In 2007, the WHO launched a roadmap for the elimination of congenital syphilis (mother to child transmission). In 2015, Cuba became the first country in the world to eliminate mother-to-child syphilis. In 2017 the WHO declared that Antigua and Barbuda, Saint Kitts and Nevis and four British Overseas Territories—Anguilla, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, and Montserrat—have been certified that they have ended transmission of mother-to-child syphilis and HIV. In 2018, Malaysia also achieved certification. Nevertheless, eradication of syphilis by all transmission methods remains unresolved and many questions about the eradication effort remain to be answered.

African trypanosomiasis

Early planning by the WHO for the eradication of African trypanosomiasis, also known as sleeping sickness, is underway as the rate of reported cases continues to decline and passive treatment is continued. The WHO aims to eliminate transmission of the Trypanosoma brucei gambiense parasite by 2030, though it acknowledges that this goal "leaves no room for complacency." The eradication and control efforts have been progressing well, with the number of reported cases dropping below 10,000 in 2009 for the first time; with only 992 cases reported in 2019 and 565 cases in 2020. The vast majority of the 565 cases in 2020 (over 60%) were recorded in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. However, some researchers have argued that total elimination may not be achievable due to human asymptomatic carriers of T. b. gambiense and non-tsetse modes of transmission.

The Pan African Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Eradication Campaign (PATTEC) works to eradicate the vector (the tsetse fly) population levels and subsequently the protozoan disease, by use of insecticide-impregnated targets, fly traps, insecticide-treated cattle, ultra-low dose aerial/ground spraying (SAT) of tsetse resting sites and the sterile insect technique (SIT). The use of SIT in Zanzibar proved effective in eliminating the entire population of tsetse flies but was expensive and is relatively impractical to use in many of the endemic countries afflicted with African trypanosomiasis.

Rabies

Because the rabies virus is almost always caught from animals, rabies eradication has focused on reducing the population of wild and stray animals, controls and compulsory quarantine on animals entering the country, and vaccination of pets and wild animals. Many island nations, including Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Malta, and the United Kingdom, managed to eliminate rabies during the twentieth century, and more recently much of continental Europe has been declared rabies-free.

Chagas disease

Chagas disease is caused by Trypanosoma cruzi and is mostly spread by Triatominae. It is endemic to 21 countries in Latin America. There are over 30,000 new cases per year and 12,000 deaths due to the disease. Eradication efforts focus on the elimination of vector-borne transmission and the elimination of the vectors themselves.

Leprosy

Since the introduction of multi-drug therapy in 1981, the prevalence of leprosy has been reduced by over 95%. The success of the treatment has prompted the WHO in 1991 to set a target of less than one case per 10,000 people (eliminate the disease as a public health risk) which was achieved in 2000. The elimination of transmission of leprosy is part of the WHO "Towards zero leprosy" strategy to be implemented until 2030. It aims to reduce transmission to zero in 120 countries and reduce the number of new cases to about 60,000 per year (from ca. 200,000 cases in 2019). These goals are supported by the Global Partnership for Zero Leprosy (GPZL) and the London Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases. However, a lack of understanding of the disease and its transmission, and the long incubation period of the M. leprae pathogen have so far prevented the formulation of a full-scale eradication strategy.

Eradicable diseases in animals

Following rinderpest, many experts believe that ovine rinderpest, or peste des petits ruminants (PPR), is the next disease amenable to global eradication. PPR is a highly contagious viral disease of goats and sheep characterized by fever, painful sores in the mouth, tongue and feet, diarrhea, pneumonia and death, especially in young animals. It is caused by a virus of the genus Morbillivirus that is related to rinderpest, measles and canine distemper.

The World Organisation for Animal Health (WOAH) prioritises African swine fever, bovine tuberculosis, foot and mouth disease, and PPR.