DNA computing is an emerging branch of unconventional computing which uses DNA, biochemistry, and molecular biology hardware, instead of the traditional electronic computing. Research and development in this area concerns theory, experiments, and applications of DNA computing. Although the field originally started with the demonstration of a computing application by Len Adleman in 1994, it has now been expanded to several other avenues such as the development of storage technologies, nanoscale imaging modalities, synthetic controllers and reaction networks, etc.

History

Leonard Adleman of the University of Southern California initially developed this field in 1994. Adleman demonstrated a proof-of-concept use of DNA as a form of computation which solved the seven-point Hamiltonian path problem. Since the initial Adleman experiments, advances have occurred and various Turing machines have been proven to be constructible.

Since then the field has expanded into several avenues. In 1995, the idea for DNA-based memory was proposed by Eric Baum who conjectured that a vast amount of data can be stored in a tiny amount of DNA due to its ultra-high density. This expanded the horizon of DNA computing into the realm of memory technology although the in vitro demonstrations were made after almost a decade.

The field of DNA computing can be categorized as a sub-field of the broader DNA nanoscience field started by Ned Seeman about a decade before Len Adleman's demonstration. Ned's original idea in the 1980s was to build arbitrary structures using bottom-up DNA self-assembly for applications in crystallography. However, it morphed into the field of structural DNA self-assembly which as of 2020 is extremely sophisticated. Self-assembled structure from a few nanometers tall all the way up to several tens of micrometers in size have been demonstrated in 2018.

In 1994, Prof. Seeman's group demonstrated early DNA lattice structures using a small set of DNA components. While the demonstration by Adleman showed the possibility of DNA-based computers, the DNA design was trivial because as the number of nodes in a graph grows, the number of DNA components required in Adleman's implementation would grow exponentially. Therefore, computer scientists and biochemists started exploring tile-assembly where the goal was to use a small set of DNA strands as tiles to perform arbitrary computations upon growth. Other avenues that were theoretically explored in the late 90's include DNA-based security and cryptography, computational capacity of DNA systems, DNA memories and disks, and DNA-based robotics.

Before 2002, Lila Kari showed that the DNA operations performed by genetic recombination in some organisms are Turing complete.

In 2003, John Reif's group first demonstrated the idea of a DNA-based walker that traversed along a track similar to a line follower robot. They used molecular biology as a source of energy for the walker. Since this first demonstration, a wide variety of DNA-based walkers have been demonstrated.

Applications, examples, and recent developments

In 1994 Leonard Adleman presented the first prototype of a DNA computer. The TT-100 was a test tube filled with 100 microliters of a DNA solution. He managed to solve an instance of the directed Hamiltonian path problem. In Adleman's experiment, the Hamiltonian Path Problem was implemented notationally as the "travelling salesman problem". For this purpose, different DNA fragments were created, each one of them representing a city that had to be visited. Every one of these fragments is capable of a linkage with the other fragments created. These DNA fragments were produced and mixed in a test tube. Within seconds, the small fragments form bigger ones, representing the different travel routes. Through a chemical reaction, the DNA fragments representing the longer routes were eliminated. The remains are the solution to the problem, but overall, the experiment lasted a week. However, current technical limitations prevent the evaluation of the results. Therefore, the experiment isn't suitable for the application, but it is nevertheless a proof of concept.

Combinatorial problems

First results to these problems were obtained by Leonard Adleman.

- In 1994: Solving a Hamiltonian path in a graph with seven summits.

- In 2002: Solving a NP-complete problem as well as a 3-SAT problem with 20 variables.

Tic-tac-toe game

In 2002, J. Macdonald, D. Stefanović and M. Stojanović created a DNA computer able to play tic-tac-toe against a human player. The calculator consists of nine bins corresponding to the nine squares of the game. Each bin contains a substrate and various combinations of DNA enzymes. The substrate itself is composed of a DNA strand onto which was grafted a fluorescent chemical group at one end, and the other end, a repressor group. Fluorescence is only active if the molecules of the substrate are cut in half. The DNA enzymes simulate logical functions. For example, such a DNA will unfold if two specific types of DNA strand are introduced to reproduce the logic function AND.

By default, the computer is considered to have played first in the central square. The human player starts with eight different types of DNA strands corresponding to the eight remaining boxes that may be played. To play box number i, the human player pours into all bins the strands corresponding to input #i. These strands bind to certain DNA enzymes present in the bins, resulting, in one of these bins, in the deformation of the DNA enzymes which binds to the substrate and cuts it. The corresponding bin becomes fluorescent, indicating which box is being played by the DNA computer. The DNA enzymes are divided among the bins in such a way as to ensure that the best the human player can achieve is a draw, as in real tic-tac-toe.

Neural network based computing

Kevin Cherry and Lulu Qian at Caltech developed a DNA-based artificial neural network that can recognize 100-bit hand-written digits. They achieved this by programming on a computer in advance with the appropriate set of weights represented by varying concentrations weight molecules which are later added to the test tube that holds the input DNA strands.

Improved speed with Localized (cache-like) Computing

One of the challenges of DNA computing is its slow speed. While DNA is a biologically compatible substrate, i.e., it can be used at places where silicon technology cannot, its computational speed is still very slow. For example, the square-root circuit used as a benchmark in the field takes over 100 hours to complete. While newer ways with external enzyme sources are reporting faster and more compact circuits, Chatterjee et al. demonstrated an interesting idea in the field to speed up computation through localized DNA circuits, a concept being further explored by other groups. This idea, while originally proposed in the field of computer architecture, has been adopted in this field as well. In computer architecture, it is very well-known that if the instructions are executed in sequence, having them loaded in the cache will inevitably lead to fast performance, also called the principle of localization. This is because with instructions in fast cache memory, there is no need swap them in and out of main memory, which can be slow. Similarly, in localized DNA computing, the DNA strands responsible for computation are fixed on a breadboard-like substrate ensuring physical proximity of the computing gates. Such localized DNA computing techniques have been shown to potentially reduce the computation time by orders of magnitude.

Renewable (or reversible) DNA computing

Subsequent research on DNA computing has produced reversible DNA computing, bringing the technology one step closer to the silicon-based computing used in (for example) PCs. In particular, John Reif and his group at Duke University have proposed two different techniques to reuse the computing DNA complexes. The first design uses dsDNA gates, while the second design uses DNA hairpin complexes. While both designs face some issues (such as reaction leaks), this appears to represent a significant breakthrough in the field of DNA computing. Some other groups have also attempted to address the gate reusability problem.

Using strand displacement reactions (SDRs), reversible proposals are presented in the "Synthesis Strategy of Reversible Circuits on DNA Computers" paper for implementing reversible gates and circuits on DNA computers by combining DNA computing and reversible computing techniques. This paper also proposes a universal reversible gate library (URGL) for synthesizing n-bit reversible circuits on DNA computers with an average length and cost of the constructed circuits better than the previous methods.

Methods

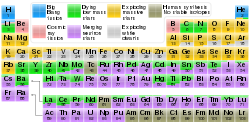

There are multiple methods for building a computing device based on DNA, each with its own advantages and disadvantages. Most of these build the basic logic gates (AND, OR, NOT) associated with digital logic from a DNA basis. Some of the different bases include DNAzymes, deoxyoligonucleotides, enzymes, and toehold exchange.

Strand displacement mechanisms

The most fundamental operation in DNA computing and molecular programming is the strand displacement mechanism. Currently, there are two ways to perform strand displacement:

- Toehold mediated strand displacement (TMSD)

- Polymerase-based strand displacement (PSD)

Toehold exchange

Besides simple strand displacement schemes, DNA computers have also been constructed using the concept of toehold exchange. In this system, an input DNA strand binds to a sticky end, or toehold, on another DNA molecule, which allows it to displace another strand segment from the molecule. This allows the creation of modular logic components such as AND, OR, and NOT gates and signal amplifiers, which can be linked into arbitrarily large computers. This class of DNA computers does not require enzymes or any chemical capability of the DNA.

Chemical reaction networks (CRNs)

The full stack for DNA computing looks very similar to a traditional computer architecture. At the highest level, a C-like general purpose programming language is expressed using a set of chemical reaction networks (CRNs). This intermediate representation gets translated to domain-level DNA design and then implemented using a set of DNA strands. In 2010, Erik Winfree's group showed that DNA can be used as a substrate to implement arbitrary chemical reactions. This opened the way to design and synthesis of biochemical controllers since the expressive power of CRNs is equivalent to a Turing machine. Such controllers can potentially be used in vivo for applications such as preventing hormonal imbalance.

DNAzymes

Catalytic DNA (deoxyribozyme or DNAzyme) catalyze a reaction when interacting with the appropriate input, such as a matching oligonucleotide. These DNAzymes are used to build logic gates analogous to digital logic in silicon; however, DNAzymes are limited to one-, two-, and three-input gates with no current implementation for evaluating statements in series.

The DNAzyme logic gate changes its structure when it binds to a matching oligonucleotide and the fluorogenic substrate it is bonded to is cleaved free. While other materials can be used, most models use a fluorescence-based substrate because it is very easy to detect, even at the single molecule limit. The amount of fluorescence can then be measured to tell whether or not a reaction took place. The DNAzyme that changes is then "used", and cannot initiate any more reactions. Because of this, these reactions take place in a device such as a continuous stirred-tank reactor, where old product is removed and new molecules added.

Two commonly used DNAzymes are named E6 and 8-17. These are popular because they allow cleaving of a substrate in any arbitrary location. Stojanovic and MacDonald have used the E6 DNAzymes to build the MAYA I and MAYA II machines, respectively; Stojanovic has also demonstrated logic gates using the 8-17 DNAzyme. While these DNAzymes have been demonstrated to be useful for constructing logic gates, they are limited by the need of a metal cofactor to function, such as Zn2+ or Mn2+, and thus are not useful in vivo.

A design called a stem loop, consisting of a single strand of DNA which has a loop at an end, are a dynamic structure that opens and closes when a piece of DNA bonds to the loop part. This effect has been exploited to create several logic gates. These logic gates have been used to create the computers MAYA I and MAYA II which can play tic-tac-toe to some extent.

Enzymes

Enzyme-based DNA computers are usually of the form of a simple Turing machine; there is analogous hardware, in the form of an enzyme, and software, in the form of DNA.

Benenson, Shapiro and colleagues have demonstrated a DNA computer using the FokI enzyme and expanded on their work by going on to show automata that diagnose and react to prostate cancer: under expression of the genes PPAP2B and GSTP1 and an over expression of PIM1 and HPN. Their automata evaluated the expression of each gene, one gene at a time, and on positive diagnosis then released a single strand DNA molecule (ssDNA) that is an antisense for MDM2. MDM2 is a repressor of protein 53, which itself is a tumor suppressor. On negative diagnosis it was decided to release a suppressor of the positive diagnosis drug instead of doing nothing. A limitation of this implementation is that two separate automata are required, one to administer each drug. The entire process of evaluation until drug release took around an hour to complete. This method also requires transition molecules as well as the FokI enzyme to be present. The requirement for the FokI enzyme limits application in vivo, at least for use in "cells of higher organisms". It should also be pointed out that the 'software' molecules can be reused in this case.

Algorithmic self-assembly

DNA nanotechnology has been applied to the related field of DNA computing. DNA tiles can be designed to contain multiple sticky ends with sequences chosen so that they act as Wang tiles. A DX array has been demonstrated whose assembly encodes an XOR operation; this allows the DNA array to implement a cellular automaton which generates a fractal called the Sierpinski gasket. This shows that computation can be incorporated into the assembly of DNA arrays, increasing its scope beyond simple periodic arrays.

Capabilities

DNA computing is a form of parallel computing in that it takes advantage of the many different molecules of DNA to try many different possibilities at once. For certain specialized problems, DNA computers are faster and smaller than any other computer built so far. Furthermore, particular mathematical computations have been demonstrated to work on a DNA computer.

DNA computing does not provide any new capabilities from the standpoint of computability theory, the study of which problems are computationally solvable using different models of computation. For example, if the space required for the solution of a problem grows exponentially with the size of the problem (EXPSPACE problems) on von Neumann machines, it still grows exponentially with the size of the problem on DNA machines. For very large EXPSPACE problems, the amount of DNA required is too large to be practical.

Alternative technologies

A partnership between IBM and Caltech was established in 2009 aiming at "DNA chips" production. A Caltech group is working on the manufacturing of these nucleic-acid-based integrated circuits. One of these chips can compute whole square roots. A compiler has been written in Perl.

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {n} ~\ {}+{}\mathrm {e} {\vphantom {A}}^{+}{}\mathrel {\longrightleftharpoons } {}{\overline {\nu }}{\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{e}}{}+{}\mathrm {p} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/28070a0758f3087bba3ae4250d2f51c97d78ab42)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {n} ~\ {}+{}\mathrm {\nu } {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{e}}{}\mathrel {\longrightleftharpoons } {}\mathrm {p} {}+{}\mathrm {e} {\vphantom {A}}^{-}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/c7f892298b08d9cd8861e592bd4d6b862ef5e886)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {p} {}+{}\mathrm {n} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} {}+{}\mathrm {\gamma } }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8edd66ec4ae73efa54a5da37e478d861a5324e97)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {p} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {\gamma } }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/78555c3239ce867ce71b9210ec4f53a08d632c52)

![{\displaystyle {{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {n} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/bf7e4f10126617c70cc314355bb411ce9e0bd4f3)

![{\displaystyle {{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {H} {}+{}\mathrm {p} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f544ed27e3ebbcdb4aed17d69966b0b39b5cbf21)

![{\displaystyle {{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {4}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {4}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {p} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/191b50329eb344d90115627d24fd3f680858baf7)

![{\displaystyle {{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {3}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {3}}}\mathrm {H} {}+{}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {2}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {2}}}\mathrm {H} {}\mathrel {\longrightarrow } {}{\vphantom {A}}_{\hphantom {}}^{\hphantom {4}}{\mkern {-1.5mu}}{\vphantom {A}}_{{\vphantom {2}}{\llap {\smash[{t}]{}}}}^{{\smash[{t}]{\vphantom {2}}}{\llap {4}}}\mathrm {He} {}+{}\mathrm {n} }}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/5121e978f2e5f9ef2a9072e80959a470c68ac04d)