Artist's impression of the Deep Impact space probe after deployment of the Impactor.

| |

| Mission type | Flyby · impactor (9P/Tempel) |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA · JPL |

| COSPAR ID | 2005-001A |

| SATCAT no. | 28517 |

| Website | www |

| Mission duration | Final: 8 years, 6 months, 26 days |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Manufacturer | Ball Aerospace · University of Maryland |

| Launch mass | Spacecraft: 601 kg (1,325 lb) Impactor: 372 kg (820 lb) |

| Dimensions | 3.3 × 1.7 × 2.3 m (10.8 × 5.6 × 7.5 ft) |

| Power | 92 W (solar array / NiH 2 battery) |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | January 12, 2005, 18:47:08 UTC |

| Rocket | Delta II 7925 |

| Launch site | Cape Canaveral SLC-17B |

| Contractor | Boeing |

| End of mission | |

| Disposal | Contact lost |

| Last contact | August 8, 2013 |

| Flyby of Tempel 1 | |

| Closest approach | July 4, 2005, 06:05 UTC |

| Distance | ~500 km (310 mi) |

| Tempel 1 impactor | |

| Impact date | July 4, 2005, 05:52 UTC |

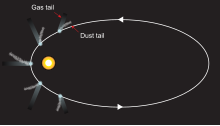

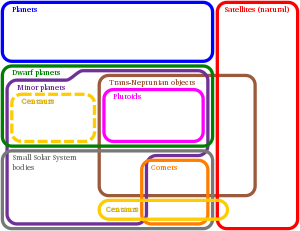

Deep Impact was a NASA space probe launched from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station on January 12, 2005. It was designed to study the interior composition of the comet Tempel 1 (9P/Tempel), by releasing an impactor into the comet. At 05:52 UTC on July 4, 2005, the Impactor successfully collided with the comet's nucleus. The impact excavated debris from the interior of the nucleus, forming an impact crater. Photographs taken by the spacecraft showed the comet to be more dusty and less icy than had been expected. The impact generated an unexpectedly large and bright dust cloud, obscuring the view of the impact crater.

Previous space missions to comets, such as Giotto, Deep Space 1, and Stardust, were fly-by missions. These missions were able to photograph and examine only the surfaces of cometary nuclei, and even then from considerable distances. The Deep Impact mission was the first to eject material from a comet's surface, and the mission garnered considerable publicity from the media, international scientists, and amateur astronomers alike.

Upon the completion of its primary mission, proposals were made to further utilize the spacecraft. Consequently, Deep Impact flew by Earth on December 31, 2007 on its way to an extended mission, designated EPOXI, with a dual purpose to study extrasolar planets and comet Hartley 2 (103P/Hartley). Communication was unexpectedly lost in September 2013 while the craft was heading for another asteroid flyby.

Scientific goals

The Deep Impact

mission was planned to help answer fundamental questions about comets,

which included what makes up the composition of the comet's nucleus,

what depth the crater would reach from the impact, and where the comet

originated in its formation.

By observing the composition of the comet, astronomers hoped to

determine how comets form based on the differences between the interior

and exterior makeup of the comet. Observations of the impact and its aftermath would allow astronomers to attempt to determine the answers to these questions.

The mission's Principal Investigator was Michael A'Hearn, an astronomer at the University of Maryland. He led the science team, which included members from Cornell University, University of Maryland, University of Arizona, Brown University, Belton Space Exploration Initiatives, JPL, University of Hawaii, SAIC, Ball Aerospace, and Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik.

Spacecraft design and instrumentation

Spacecraft overview

The spacecraft

consists of two main sections, the 372-kilogram (820 lb) copper-core

"Smart Impactor" that impacted the comet, and the 601 kg (1,325 lb)

"Flyby" section, which imaged the comet from a safe distance during the

encounter with Tempel 1.

The Flyby spacecraft is about 3.3 meters (10.8 ft) long, 1.7 meters (5.6 ft) wide and 2.3 meters (7.5 ft) high. It includes two solar panels, a debris shield, and several science instruments for imaging, infrared spectroscopy, and optical navigation to its destination near the comet. The spacecraft also carried two cameras, the High Resolution Imager

(HRI), and the Medium Resolution Imager (MRI). The HRI is an imaging

device that combines a visible-light camera with a filter wheel, and an

imaging infrared spectrometer

called the "Spectral Imaging Module" or SIM that operates on a spectral

band from 1.05 to 4.8 micrometres. It has been optimized for observing

the comet's nucleus. The MRI is the backup device, and was used

primarily for navigation during the final 10-day approach. It also has a

filter wheel, with a slightly different set of filters.

The Impactor section of the spacecraft contains an instrument

that is optically identical to the MRI, called the Impactor Targeting

Sensor (ITS), but without the filter wheel. Its dual purpose was to

sense the Impactor's trajectory, which could then be adjusted up to four

times between release and impact, and to image the comet from close

range. As the Impactor neared the comet's surface, this camera took

high-resolution pictures of the nucleus (as good as 0.2 meters per pixel

[7.9 in/px]) that were transmitted in real-time to the Flyby spacecraft

before it and the Impactor were destroyed. The final image taken by the

Impactor was snapped only 3.7 seconds before impact.

The Impactor's payload, dubbed the "Cratering Mass", was 100% copper, with a weight of 100 kg. Including this cratering mass, copper formed 49% of total mass of the Impactor (with aluminium at 24% of the total mass);

this was to minimize interference with scientific measurements. Since

copper was not expected to be found on a comet, scientists could ignore

copper's signature in any spectrometer readings. Instead of using explosives, it was also cheaper to use copper as the payload.

Explosives would also have been superfluous. At its closing

velocity of 10.2 km/s, the Impactor's kinetic energy was equivalent to

4.8 metric tons of TNT, considerably more than its actual mass of only

372 kg.

The mission coincidentally shared its name with the 1998 film, Deep Impact, in which a comet strikes the Earth.

Mission profile

Cameras of the Flyby spacecraft, HRI at right, MRI at left

Deep Impact prior to launch on a Delta II rocket

Following its launch from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station pad SLC-17B at 18:47 UTC on January 12, 2005, the Deep Impact

spacecraft traveled 429 million km (267 million mi) in 174 days to

reach comet Tempel 1 at a cruising speed of 28.6 km/s (103,000 km/h;

64,000 mph).

Once the spacecraft reached the vicinity of the comet on July 3, 2005,

it separated into the Impactor and Flyby sections. The Impactor used its

thrusters to move into the path of the comet, impacting 24 hours later

at a relative speed of 10.3 km/s (37,000 km/h; 23,000 mph). The Impactor delivered 1.96×1010 joules of kinetic energy—the equivalent of 4.7 tons of TNT.

Scientists believed that the energy of the high-velocity collision

would be sufficient to excavate a crater up to 100 m (330 ft) wide,

larger than the bowl of the Roman Colosseum. The size of the crater was still not known one year after the impact. The 2007 Stardust spacecraft's NExT mission determined the crater's diameter to be 150 meters (490 ft).

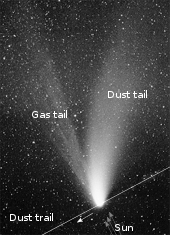

Just minutes after the impact, the Flyby probe passed by the

nucleus at a close distance of 500 km (310 mi), taking pictures of the

crater position, the ejecta plume, and the entire cometary nucleus. The entire event was also photographed by Earth-based telescopes and orbital observatories, including Hubble, Chandra, Spitzer, and XMM-Newton. The impact was also observed by cameras and spectroscopes on board Europe's Rosetta spacecraft, which was about 80 million km (50 million mi) from the comet at the time of impact. Rosetta determined the composition of the gas and dust cloud that was kicked up by the impact.

Mission events

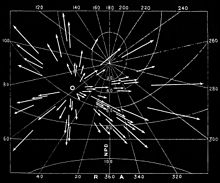

Animation of Deep Impact's trajectory from January 12, 2005, to August 8, 2013

Deep Impact · Tempel 1 · Earth · 103P/Hartley

Deep Impact · Tempel 1 · Earth · 103P/Hartley

Before launch

A

comet-impact mission was first proposed to NASA in 1996, but at the

time, NASA engineers were skeptical that the target could be hit. In 1999, a revised and technologically upgraded mission proposal, dubbed Deep Impact, was accepted and funded as part of NASA's Discovery Program of low-cost spacecraft. The two spacecraft (Impactor and Flyby) and the three main instruments were built and integrated by Ball Aerospace & Technologies in Boulder, Colorado.

Developing the software for the spacecraft took 18 months and the

application code consisted of 20,000 lines and 19 different application

threads. The total cost of developing the spacecraft and completing its mission reached US$330 million.

Launch and commissioning phase

The

probe was originally scheduled for launch on December 30, 2004, but

NASA officials delayed its launch, in order to allow more time for

testing the software. It was successfully launched from Cape Canaveral on January 12, 2005 at 1:47 pm EST (1847 UTC) by a Delta II rocket.

Deep Impact's

state of health was uncertain during the first day after launch.

Shortly after entering orbit around the Sun and deploying its solar

panels, the probe switched itself to safe mode. The cause of the problem was simply an incorrect temperature limit in the fault protection logic for the spacecraft's RCS thruster

catalyst beds. The spacecraft's thrusters were used to detumble the

spacecraft following third stage separation. On January 13, 2005, NASA

announced that the probe was out of safe mode and healthy.

On February 11, 2005, Deep Impact's

rockets were fired as planned to correct the spacecraft's course. This

correction was so precise that the next planned correction maneuver on

March 31, 2005, was unnecessary and canceled. The "commissioning phase"

verified that all instruments were activated and checked out. During

these tests it was found that the HRI images were not in focus after it

underwent a bake-out period.

After mission members investigated the problem, on June 9, 2005, it was

announced that by using image processing software and the mathematical

technique of deconvolution, the HRI images could be corrected to restore much of the resolution anticipated.

Cruise phase

Comet Tempel 1 imaged on April 25 by the Deep Impact spacecraft

The "cruise phase" began on March 25, 2005, immediately after the

commissioning phase was completed. This phase continued until about 60

days before the encounter with comet Tempel 1. On April 25, 2005, the

probe acquired the first image of its target at a distance of

64 million km (40 million mi).

On May 4, 2005, the spacecraft executed its second trajectory

correction maneuver. Burning its rocket engine for 95 seconds, the

spacecraft speed was changed by 18.2 km/h (11.3 mph).

Rick Grammier, the project manager for the mission at NASA's Jet

Propulsion Laboratory, reacted to the maneuver stating that "spacecraft

performance has been excellent, and this burn was no different... it was

a textbook maneuver that placed us right on the money."

Approach phase

The

approach phase extended from 60 days before encounter (May 5, 2005)

until five days before encounter. Sixty days out was the earliest time

that the Deep Impact spacecraft was expected to detect the comet

with its MRI camera. In fact, the comet was spotted ahead of schedule,

69 days before impact (see Cruise phase

above). This milestone marks the beginning of an intensive period of

observations to refine knowledge of the comet's orbit and study the

comet's rotation, activity, and dust environment.

On June 14 and 22, 2005, Deep Impact observed two outbursts of activity from the comet, the latter being six times larger than the former. The spacecraft studied the images of various distant stars to determine its current trajectory and position.

Don Yeomans, a mission co-investigator for JPL pointed out that "it

takes 7½ minutes for the signal to get back to Earth, so you cannot

joystick this thing. You have to rely on the fact that the Impactor is a

smart spacecraft as is the Flyby spacecraft. So you have to build in

the intelligence ahead of time and let it do its thing."

On June 23, 2005, the first of the two final trajectory correct

maneuvers (targeting maneuver) was successfully executed. A 6 m/s

(20 ft/s) velocity change was needed to adjust the flight path towards

the comet and target the Impactor at a window in space about 100

kilometers (62 mi) wide.

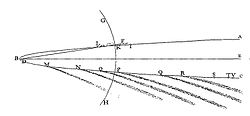

Impact phase

Deep Impact comet encounter sequence

Impact phase began nominally on June 29, 2005, five days before

impact. The Impactor successfully separated from the Flyby spacecraft on

July 3 at 6:00 UTC (6:07 UTC ERT). The first images from the instrumented Impactor were seen two hours after separation.

The Flyby spacecraft performed one of two divert maneuvers to

avoid damage. A 14-minute burn was executed which slowed down the

spacecraft. It was also reported that the communication link between the

Flyby and the Impactor was functioning as expected. The Impactor executed three correction maneuvers in the final two hours before impact.

The Impactor was maneuvered to plant itself in front of the comet, so that Tempel 1 would collide with it. Impact occurred at 05:45 UTC (05:52 UTC ERT,

+/- up to three minutes, one-way light time = 7m 26s) on the morning of

July 4, 2005, within one second of the expected time for impact.

The impactor returned images as late as three seconds before

impact. Most of the data captured was stored on board the Flyby

spacecraft, which radioed approximately 4,500 images from the HRI, MRI,

and ITS cameras to Earth over the next few days. The energy from the collision was similar in size to exploding five tons of dynamite and the comet shone six times brighter than normal.

A mission timeline is located at Impact Phase Timeline (NASA).

Results

Mission team members celebrate after the impact with the comet

Mission control did not become aware of the Impactor's success until five minutes later at 05:57 UTC. Don Yeomans confirmed the results for the press, "We hit it just exactly where we wanted to" and JPL Director Charles Elachi stated "The success exceeded our expectations."

In the post-impact briefing on July 4, 2005, at 08:00 UTC, the first processed images revealed existing craters

on the comet. NASA scientists stated they could not see the new crater

that had formed from the Impactor, but it was later discovered to be

about 100 meters wide and up to 30 meters (98 ft) deep.

Lucy McFadden, one of the co-investigators of the impact, stated "We

didn't expect the success of one part of the mission [bright dust cloud]

to affect a second part [seeing the resultant crater]. But that is part

of the fun of science, to meet with the unexpected." Analysis of data from the Swift X-ray telescope

showed that the comet continued outgassing from the impact for 13 days,

with a peak five days after impact. A total of 5 million kg

(11 million lb) of water and between 10 and 25 million kg (22 and 55 million lb) of dust were lost from the impact.

Initial results were surprising as the material excavated by the

impact contained more dust and less ice than had been expected. The only

models of cometary structure astronomers could positively rule out were

the very porous ones which had comets as loose aggregates of material.

In addition, the material was finer than expected; scientists compared

it to talcum powder rather than sand. Other materials found while studying the impact included clays, carbonates, sodium, and crystalline silicates which were found by studying the spectroscopy of the impact. Clays and carbonates usually require liquid water to form and sodium is rare in space.

Observations also revealed that the comet was about 75% empty space,

and one astronomer compared the outer layers of the comet to the same

makeup of a snow bank.

Astronomers have expressed interest in more missions to different

comets to determine if they share similar compositions or if there are

different materials found deeper within comets that were produced at the

time of the Solar System's formation.

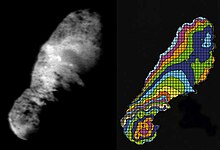

'Before and after' comparison images from Deep Impact and Stardust, showing the crater formed by Deep Impact on the right hand image.

Astronomers hypothesized, based on its interior chemistry, that the comet formed in the Uranus and Neptune Oort cloud

region of the Solar System. A comet which forms farther from the Sun is

expected to have greater amounts of ices with low freezing

temperatures, such as ethane,

which was present in Tempel 1. Astronomers believe that other comets

with compositions similar to Tempel 1 are likely to have formed in the

same region.

Crater

Because the quality of the images of the crater formed during the Deep Impact

collision was not satisfactory, on July 3, 2007, NASA approved the New

Exploration of Tempel 1 (or NExT) mission. The mission utilized the

already existing Stardust spacecraft, which had studied Comet Wild 2 in 2004. Stardust

was placed into a new orbit so that it passed by Tempel 1 at a distance

of approximately 200 km (120 mi) on February 15, 2011, at 04:42 UTC. This was the first time that a comet was visited by two probes on separate occasions (1P/Halley

had been visited by several probes within a few weeks in 1986), and it

provided an opportunity to better observe the crater that was created by

Deep Impact as well as observing the changes caused by the comet's latest close approach to the Sun.

On February 15, NASA scientists identified the crater formed by Deep Impact in images from Stardust.

The crater is estimated to be 150 meters (490 ft) in diameter, and has a

bright mound in the center likely created when material from the impact

fell back into the crater.

Public interest

Media coverage

The image of the impact which was widely circulated in the media

The impact was a substantial news event reported and discussed

online, in print, and on television. There was a genuine suspense

because experts held widely differing opinions over the result of the

impact. Various experts debated whether the Impactor would go straight

through the comet and out the other side, would create an impact crater,

would open up a hole in the interior of the comet, and other theories.

However, twenty-four hours before impact, the flight team at JPL began

privately expressing a high level of confidence that, barring any

unforeseen technical glitches, the spacecraft would intercept Tempel 1.

One senior personnel member stated "All we can do now is sit back and

wait. Everything we can technically do to ensure impact has been done."

In the final minutes as the Impactor hit the comet, more than 10,000

people watched the collision on a giant movie screen at Hawaii's Waikīkī Beach.

Experts came up with a range of soundbites to summarize the mission to the public. Iwan Williams of Queen Mary University of London, said "It was like a mosquito hitting a 747. What we've found is that the mosquito didn't splat on the surface; it's actually gone through the windscreen."

One day after the impact Marina Bay, a Russian astrologer, sued NASA for US$300 million for the impact which "ruin[ed] the natural balance of forces in the universe."

Her lawyer asked the public to volunteer to help in the claim by

declaring "The impact changed the magnetic properties of the comet, and

this could have affected mobile telephony here on Earth. If your phone

went down this morning, ask yourself Why? and then get in touch with

us."

On August 9, 2005 the Presnensky Court of Moscow ruled against Bay,

although she did attempt to appeal the result. One Russian physicist

said that the impact had no effect on Earth and "the change to the orbit

of the comet after the collision was only about 10 cm (3.9 in)."

Send Your Name To A Comet campaign

The CD containing the 625,000 names is added to the Impactor

The mission was notable for one of its promotional campaigns, "Send Your Name To A Comet!". Visitors to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory's

website were invited to submit their name between May 2003 and January

2004, and the names gathered—some 625,000 in all—were then burnt onto a

mini-CD, which was attached to the Impactor.

Dr. Don Yeomans, a member of the spacecraft's scientific team, stated

"this is an opportunity to become part of an extraordinary space

mission ... when the craft is launched in December 2004, yours and the

names of your loved-ones can hitch along for the ride and be part of

what may be the best space fireworks show in history." The idea was credited with driving interest in the mission.

Reaction from China

Chinese researchers used the Deep Impact

mission as an opportunity to highlight the efficiency of American

science because public support ensured the possibility of funding

long-term research. By contrast, "in China, the public usually has no

idea what our scientists are doing, and limited funding for the

promotion of science weakens people's enthusiasm for research."

Two days after the U.S. mission succeeded in having a probe

collide with a comet, China revealed a plan for what it called a "more

clever" version of the mission: landing a probe on a small comet or asteroid to push it off course. China said it would begin the mission after sending a probe to the Moon.

Contributions from amateur astronomers

Deep Impact participation certificate of Maciej Szczepańczyk

Since observing time on large, professional telescopes such as Keck or Hubble is always scarce, the Deep Impact scientists called upon "advanced amateur, student, and professional astronomers"

to use small telescopes to make long-term observations of the target

comet before and after impact. The purpose of these observations was to

look for "volatile outgassing, dust coma development and dust production

rates, dust tail development, and jet activity and outbursts." By mid-2007, amateur astronomers had submitted over a thousand CCD images of the comet.

One notable amateur observation was by students from schools in

Hawaii, working with US and UK scientists, who during the press

conference took live images using the Faulkes Automatic Telescope

in Hawaii (the students operated the telescope over the Internet) and

were one of the first groups to get images of the impact. One amateur

astronomer reported seeing a structureless bright cloud around the

comet, and an estimated 2 magnitude increase in brightness after the impact. Another amateur published a map of the crash area from NASA images.

Musical tribute

The Deep Impact mission coincided with celebrations in the Los Angeles area marking the 50th anniversary of "Rock Around the Clock" by Bill Haley & His Comets becoming the first rock and roll

single to reach No. 1 on the recording sales charts. Within 24 hours of

the mission's success, a 2-minute music video produced by Martin Lewis had been created using images of the impact itself combined with computer animation of the Deep Impact

probe in flight, interspersed with footage of Bill Haley & His

Comets performing in 1955 and the surviving original members of The

Comets performing in March 2005. The video was posted to NASA's website for a couple of weeks afterwards.

On July 5, 2005, the surviving original members of The Comets

(ranging in age from 71–84) performed a free concert for hundreds of

employees of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory to help them celebrate the

mission's success. This event received worldwide press attention. In February 2006, the International Astronomical Union citation that officially named asteroid 79896 Billhaley included a reference to the JPL concert.

Extended mission

Deep Impact embarked on an extended mission designated EPOXI (Extrasolar Planet Observation and Deep Impact Extended Investigation) to visit other comets, after being put to sleep in 2005 upon completion of the Tempel 1 mission.

Comet Boethin plan

Its first extended visit was to do a flyby of Comet Boethin, but with some complications. On July 21, 2005, Deep Impact

executed a trajectory correction maneuver that allows the spacecraft to

use Earth's gravity to begin a new mission in a path towards another

comet.

The original plan was for a December 5, 2008, flyby of Comet

Boethin, coming within 700 kilometers (430 mi) of the comet. Michael

A'Hearn, the Deep Impact team leader, explained "We propose to

direct the spacecraft for a flyby of Comet Boethin to investigate

whether the results found at Comet Tempel 1 are unique or are also found

on other comets." The $40 million mission would provide about half of the information as the collision of Tempel 1 but at a fraction of the cost. Deep Impact would use its spectrometer to study the comet's surface composition and its telescope for viewing the surface features.

However, as the December 2007 Earth gravity assist approached, astronomers were unable to locate Comet Boethin, which may have broken up into pieces too faint to be observed. Consequently, its orbit could not be calculated with sufficient precision to permit a flyby.

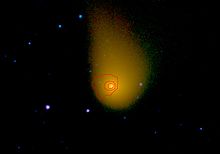

Flyby of Comet Hartley 2

Comet Hartley 2 on November 4, 2010

In November 2007 the JPL team targeted Deep Impact toward Comet Hartley 2. However, this would require an extra two years of travel for Deep Impact (including earth gravity assists in December 2007 and December 2008).

On May 28, 2010, a burn of 11.3 seconds was conducted, to enable the

June 27 Earth fly-by to be optimized for the transit to Hartley 2 and

fly-by on November 4. The velocity change was 0.1 m/s (0.33 ft/s).

On November 4, 2010, the Deep Impact extended mission (EPOXI) returned images from comet Hartley 2.

EPOXI came within 700 kilometers (430 mi) of the comet, returning

detailed photographs of the "peanut" shaped cometary nucleus and several

bright jets. The probe's medium-resolution instrument captured the

photographs.

Comet Garradd (C/2009 P1)

Deep Impact observed Comet Garradd (C/2009 P1)

from February 20 to April 8, 2012, using its Medium Resolution

Instrument, through a variety of filters. The comet was 1.75–2.11 AU (262–316 million km) from the Sun and 1.87–1.30 AU

(280–194 million km) from the spacecraft. It was found that the

outgassing from the comet varies with a period of 10.4 hours, which is

presumed to be due to the rotation of its nucleus. The dry ice content

of the comet was measured and found to be about ten percent of its water

ice content by number of molecules.

Possible mission to asteroid (163249) 2002 GT

At the end of 2011, Deep Impact was re-targeted towards asteroid (163249) 2002 GT

which it would reach in January 2020. At the time of re-targeting,

whether or not a related science mission would be carried out in 2020

was yet to be determined, based on NASA's budget and the health of the

probe. A 71-second engine burn on October 4, 2012, changed the probe's velocity by 2 m/s (6.6 ft/s) to keep the mission on track.

Comet C/2012 S1 (ISON)

In February 2013, Deep Impact observed Comet ISON. The comet remained observable until March 2013.

Contact lost and end of mission

On

September 3, 2013, a mission update was posted to the EPOXI mission

status website, stating "Communication with the spacecraft was lost some

time between August 11 and August 14 ... The last communication was on

August 8. ... the team on August 30 determined the cause of the problem.

The team is now trying to determine how best to try to recover

communication."

On September 10, 2013, a Deep Impact mission status report

explained that mission controllers believe the computers on the

spacecraft are continuously rebooting themselves and so are unable to

issue any commands to the vehicle's thrusters. As a result of this

problem, communication with the spacecraft was explained to be more

difficult, as the orientation of the vehicle's antennas is unknown.

Additionally, the solar panels on the vehicle may no longer be

positioned correctly for generating power.

On September 20, 2013, NASA abandoned further attempts to contact the craft. According to A'Hearn, the most probable reason of software malfunction was a Y2K-like problem. August 11, 2013, 00:38:49, was 232

of one-tenth seconds from January 1, 2000, leading to speculation that a

system on the craft tracked time in one-tenth second increments since

January 1, 2000, and stored it in a signed 32-bit integer, which then overflowed at this time, similar to the Year 2038 problem.