From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

DNA damage resulting in multiple broken chromosomes

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a

cell identifies and corrects damage to the

DNA molecules that encode its

genome. In human cells, both normal

metabolic activities and environmental factors such as

radiation can cause DNA damage, resulting in as many as 1

million individual

molecular lesions per cell per day. Many of these lesions cause structural damage to the DNA molecule and can alter or eliminate the cell's ability to

transcribe the

gene that the affected DNA encodes. Other lesions induce potentially harmful

mutations in the cell's genome, which affect the survival of its daughter cells after it undergoes

mitosis.

As a consequence, the DNA repair process is constantly active as it

responds to damage in the DNA structure. When normal repair processes

fail, and when cellular

apoptosis does not occur, irreparable DNA damage may occur, including double-strand breaks and

DNA crosslinkages (interstrand crosslinks or ICLs). This can eventually lead to malignant tumors, or

cancer as per the

two hit hypothesis.

The rate of DNA repair is dependent on many factors, including

the cell type, the age of the cell, and the extracellular environment. A

cell that has accumulated a large amount of DNA damage, or one that no

longer effectively repairs damage incurred to its DNA, can enter one of

three possible states:

- an irreversible state of dormancy, known as senescence

- cell suicide, also known as apoptosis or programmed cell death

- unregulated cell division, which can lead to the formation of a tumor that is cancerous

The DNA repair ability of a cell is vital to the integrity of its

genome and thus to the normal functionality of that organism. Many genes

that were initially shown to influence

life span have turned out to be involved in DNA damage repair and protection.

Paul Modrich talks about himself and his work in DNA repair.

DNA damage

DNA damage, due to environmental factors and normal

metabolic processes inside the cell, occurs at a rate of 10,000 to 1,000,000 molecular lesions per cell per day.

While this constitutes only 0.000165% of the human genome's

approximately 6 billion bases (3 billion base pairs), unrepaired lesions

in critical genes (such as

tumor suppressor genes) can impede a cell's ability to carry out its function and appreciably increase the likelihood of

tumor formation and contribute to

tumour heterogeneity.

The vast majority of DNA damage affects the

primary structure

of the double helix; that is, the bases themselves are chemically

modified. These modifications can in turn disrupt the molecules' regular

helical structure by introducing non-native chemical bonds or bulky

adducts that do not fit in the standard double helix. Unlike

proteins and

RNA, DNA usually lacks

tertiary structure and therefore damage or disturbance does not occur at that level. DNA is, however,

supercoiled and wound around "packaging" proteins called

histones (in eukaryotes), and both superstructures are vulnerable to the effects of DNA damage.

Sources

DNA damage can be subdivided into two main types:

- endogenous damage such as attack by reactive oxygen species produced from normal metabolic byproducts (spontaneous mutation), especially the process of oxidative deamination

- also includes replication errors

- exogenous damage caused by external agents such as

- ultraviolet [UV 200–400 nm] radiation from the sun or other artificial light sources

- other radiation frequencies, including x-rays and gamma rays

- hydrolysis or thermal disruption

- certain plant toxins

- human-made mutagenic chemicals, especially aromatic compounds that act as DNA intercalating agents

- viruses

The replication of damaged DNA before cell division can lead to the

incorporation of wrong bases opposite damaged ones. Daughter cells that

inherit these wrong bases carry mutations from which the original DNA

sequence is unrecoverable (except in the rare case of a

back mutation, for example, through

gene conversion).

Types

There are several types of damage to DNA due to endogenous cellular processes:

- oxidation of bases [e.g. 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-oxoG)] and generation of DNA strand interruptions from reactive oxygen species,

- alkylation of bases (usually methylation), such as formation of 7-methylguanosine, 1-methyladenine, 6-O-Methylguanine

- hydrolysis of bases, such as deamination, depurination, and depyrimidination.

- "bulky adduct formation" (e.g., benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide-dG adduct, aristolactam I-dA adduct)

- mismatch of bases, due to errors in DNA replication,

in which the wrong DNA base is stitched into place in a newly forming

DNA strand, or a DNA base is skipped over or mistakenly inserted.

- Monoadduct damage cause by change in single nitrogenous base of DNA

- Diadduct damage

Damage caused by exogenous agents comes in many forms. Some examples are:

- UV-B light causes crosslinking between adjacent cytosine and thymine bases creating pyrimidine dimers. This is called direct DNA damage.

- UV-A light creates mostly free radicals. The damage caused by free radicals is called indirect DNA damage.

- Ionizing radiation such as that created by radioactive decay or in cosmic rays

causes breaks in DNA strands. Intermediate-level ionizing radiation

may induce irreparable DNA damage (leading to replicational and

transcriptional errors needed for neoplasia or may trigger viral

interactions) leading to pre-mature aging and cancer.

- Thermal disruption at elevated temperature increases the rate of depurination (loss of purine bases from the DNA backbone) and single-strand breaks. For example, hydrolytic depurination is seen in the thermophilic bacteria, which grow in hot springs at 40–80 °C. The rate of depurination (300 purine

residues per genome per generation) is too high in these species to be

repaired by normal repair machinery, hence a possibility of an adaptive response cannot be ruled out.

- Industrial chemicals such as vinyl chloride and hydrogen peroxide, and environmental chemicals such as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

found in smoke, soot and tar create a huge diversity of DNA adducts-

ethenobases, oxidized bases, alkylated phosphotriesters and crosslinking of DNA, just to name a few.

UV damage, alkylation/methylation, X-ray damage and oxidative damage

are examples of induced damage. Spontaneous damage can include the loss

of a base, deamination, sugar

ring puckering

and tautomeric shift. Constitutive (spontaneous) DNA damage caused by

endogenous oxidants can be detected as a low level of histone H2AX

phosphorylation in untreated cells.

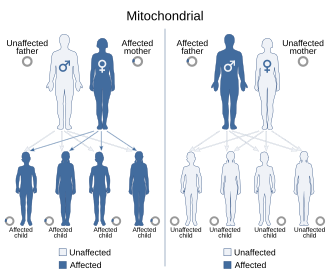

Nuclear versus mitochondrial

In human cells, and

eukaryotic cells in general, DNA is found in two cellular locations – inside the

nucleus and inside the

mitochondria. Nuclear DNA (nDNA) exists as

chromatin during non-replicative stages of the

cell cycle and is condensed into aggregate structures known as

chromosomes during

cell division. In either state the DNA is highly compacted and wound up around bead-like proteins called

histones.

Whenever a cell needs to express the genetic information encoded in its

nDNA the required chromosomal region is unravelled, genes located

therein are expressed, and then the region is condensed back to its

resting conformation. Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) is located inside

mitochondria

organelles,

exists in multiple copies, and is also tightly associated with a number

of proteins to form a complex known as the nucleoid. Inside

mitochondria,

reactive oxygen species (ROS), or

free radicals, byproducts of the constant production of

adenosine triphosphate (ATP) via

oxidative phosphorylation,

create a highly oxidative environment that is known to damage mtDNA. A

critical enzyme in counteracting the toxicity of these species is

superoxide dismutase, which is present in both the mitochondria and

cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells.

Senescence and apoptosis

Senescence, an irreversible process in which the cell no longer

divides, is a protective response to the shortening of the

chromosome ends. The telomeres are long regions of repetitive

noncoding DNA that cap chromosomes and undergo partial degradation each time a cell undergoes division (see

Hayflick limit). In contrast,

quiescence is a reversible state of cellular dormancy that is unrelated to genome damage.

Senescence in cells may serve as a functional alternative to apoptosis

in cases where the physical presence of a cell for spatial reasons is

required by the organism,

which serves as a "last resort" mechanism to prevent a cell with

damaged DNA from replicating inappropriately in the absence of

pro-growth

cellular signaling. Unregulated cell division can lead to the formation of a tumor,

which is potentially lethal to an organism. Therefore, the induction of

senescence and apoptosis is considered to be part of a strategy of

protection against cancer.

Mutation

It is

important to distinguish between DNA damage and mutation, the two major

types of error in DNA. DNA damage and mutation are fundamentally

different. Damage results in physical abnormalities in the DNA, such as

single- and double-strand breaks,

8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine

residues, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon adducts. DNA damage can

be recognized by enzymes, and thus can be correctly repaired if

redundant information, such as the undamaged sequence in the

complementary DNA strand or in a homologous chromosome, is available for

copying. If a cell retains DNA damage, transcription of a gene can be

prevented, and thus translation into a protein will also be blocked.

Replication may also be blocked or the cell may die.

In contrast to DNA damage, a mutation is a change in the base

sequence of the DNA. A mutation cannot be recognized by enzymes once the

base change is present in both DNA strands, and thus a mutation cannot

be repaired. At the cellular level, mutations can cause alterations in

protein function and regulation. Mutations are replicated when the cell

replicates. In a population of cells, mutant cells will increase or

decrease in frequency according to the effects of the mutation on the

ability of the cell to survive and reproduce.

Although distinctly different from each other, DNA damage and

mutation are related because DNA damage often causes errors of DNA

synthesis during replication or repair; these errors are a major source

of mutation.

Given these properties of DNA damage and mutation, it can be seen

that DNA damage is a special problem in non-dividing or slowly-dividing

cells, where unrepaired damage will tend to accumulate over time. On

the other hand, in rapidly-dividing cells, unrepaired DNA damage that

does not kill the cell by blocking replication will tend to cause

replication errors and thus mutation. The great majority of mutations

that are not neutral in their effect are deleterious to a cell's

survival. Thus, in a population of cells composing a tissue with

replicating cells, mutant cells will tend to be lost. However,

infrequent mutations that provide a survival advantage will tend to

clonally expand at the expense of neighboring cells in the tissue. This

advantage to the cell is disadvantageous to the whole organism, because

such mutant cells can give rise to cancer. Thus, DNA damage in

frequently dividing cells, because it gives rise to mutations, is a

prominent cause of cancer. In contrast, DNA damage in

infrequently-dividing cells is likely a prominent cause of aging.

Mechanisms

Cells cannot function if DNA damage corrupts the integrity and accessibility of essential information in the

genome

(but cells remain superficially functional when non-essential genes are

missing or damaged). Depending on the type of damage inflicted on the

DNA's double helical structure, a variety of repair strategies have

evolved to restore lost information. If possible, cells use the

unmodified complementary strand of the DNA or the sister

chromatid

as a template to recover the original information. Without access to a

template, cells use an error-prone recovery mechanism known as

translesion synthesis as a last resort.

Damage to DNA alters the spatial configuration of the helix, and

such alterations can be detected by the cell. Once damage is localized,

specific DNA repair molecules bind at or near the site of damage,

inducing other molecules to bind and form a complex that enables the

actual repair to take place.

Direct reversal

Cells

are known to eliminate three types of damage to their DNA by chemically

reversing it. These mechanisms do not require a template, since the

types of damage they counteract can occur in only one of the four bases.

Such direct reversal mechanisms are specific to the type of damage

incurred and do not involve breakage of the phosphodiester backbone. The

formation of

pyrimidine dimers upon irradiation with UV light results in an abnormal covalent bond between adjacent pyrimidine bases. The

photoreactivation process directly reverses this damage by the action of the enzyme

photolyase, whose activation is obligately dependent on energy absorbed from

blue/UV light (300–500 nm

wavelength) to promote catalysis. Photolyase, an old enzyme present in

bacteria,

fungi, and most

animals no longer functions in humans, who instead use

nucleotide excision repair

to repair damage from UV irradiation. Another type of damage,

methylation of guanine bases, is directly reversed by the protein methyl

guanine methyl transferase (MGMT), the bacterial equivalent of which is

called

ogt. This is an expensive process because each MGMT molecule can be used only once; that is, the reaction is

stoichiometric rather than

catalytic. A generalized response to methylating agents in bacteria is known as the

adaptive response and confers a level of resistance to alkylating agents upon sustained exposure by upregulation of alkylation repair enzymes. The third type of DNA damage reversed by cells is certain methylation of the bases cytosine and adenine.

Single-strand damage

Structure of the base-excision repair enzyme

uracil-DNA glycosylase excising a hydrolytically-produced uracil residue from DNA. The uracil residue is shown in yellow.

When only one of the two strands of a double helix has a defect, the

other strand can be used as a template to guide the correction of the

damaged strand. In order to repair damage to one of the two paired

molecules of DNA, there exist a number of

excision repair

mechanisms that remove the damaged nucleotide and replace it with an

undamaged nucleotide complementary to that found in the undamaged DNA

strand.

- Base excision repair

(BER): damaged single bases or nucleotides are most commonly repaired

by removing the base or the nucleotide involved and then inserting the

correct base or nucleotide. In base excision repair, a glycosylase

enzyme removes the damaged base from the DNA by cleaving the bond

between the base and the deoxyribose. These enzymes remove a single base

to create an apurinic or apyrimidinic site (AP site). Enzymes called AP endonucleases nick

the damaged DNA backbone at the AP site. DNA polymerase then removes

the damaged region using its 5’ to 3’ exonuclease activity and

correctly synthesizes the new strand using the complementary strand as a

template. The gap is then sealed by enzyme DNA ligase.

- Nucleotide excision repair (NER): bulky, helix-distorting damage, such as pyrimidine dimerization

caused by UV light is usually repaired by a three-step process. First

the damage is recognized, then 12-24 nucleotide-long strands of DNA are

removed both upstream and downstream of the damage site by endonucleases, and the removed DNA region is then resynthesized. NER is a highly evolutionarily conserved repair mechanism and is used in nearly all eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells. In prokaryotes, NER is mediated by Uvr proteins. In eukaryotes, many more proteins are involved, although the general strategy is the same.

- Mismatch repair systems are present in essentially all cells to correct errors that are not corrected by proofreading.

These systems consist of at least two proteins. One detects the

mismatch, and the other recruits an endonuclease that cleaves the newly

synthesized DNA strand close to the region of damage. In E. coli ,

the proteins involved are the Mut class proteins: MutS, MutL, and MutH.

In most Eukaryotes, the analog for MutS is MSH and the analog for MutL

is MLH. MutH is only present in bacteria. This is followed by removal of

damaged region by an exonuclease, resynthesis by DNA polymerase, and

nick sealing by DNA ligase.

Double-strand breaks

Double-strand break repair pathway models

Double-strand breaks, in which both strands in the double helix are

severed, are particularly hazardous to the cell because they can lead to

genome rearrangements. In fact, when a double-strand break is

accompanied by a cross-linkage joining the two strands at the same

point, neither strand can be used as a template for the repair

mechanisms, so that the cell will not be able to complete mitosis when

it next divides, and will either die or, in rare cases, undergo a

mutation. Three mechanisms exist to repair double-strand breaks (DSBs):

non-homologous end joining (NHEJ),

microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ), and

homologous recombination (HR). In an

in vitro system, MMEJ occurred in mammalian cells at the levels of 10–20% of HR when both HR and NHEJ mechanisms were also available.

DNA

ligase, shown above repairing chromosomal damage, is an enzyme that

joins broken nucleotides together by catalyzing the formation of an

internucleotide

ester bond between the phosphate backbone and the deoxyribose nucleotides.

In NHEJ,

DNA Ligase IV, a specialized

DNA ligase that forms a complex with the cofactor

XRCC4, directly joins the two ends.

To guide accurate repair, NHEJ relies on short homologous sequences

called microhomologies present on the single-stranded tails of the DNA

ends to be joined. If these overhangs are compatible, repair is usually

accurate.

NHEJ can also introduce mutations during repair. Loss of damaged

nucleotides at the break site can lead to deletions, and joining of

nonmatching termini forms insertions or translocations. NHEJ is

especially important before the cell has replicated its DNA, since there

is no template available for repair by homologous recombination. There

are "backup" NHEJ pathways in higher

eukaryotes. Besides its role as a genome caretaker, NHEJ is required for joining hairpin-capped double-strand breaks induced during

V(D)J recombination, the process that generates diversity in

B-cell and

T-cell receptors in the

vertebrate immune system.

Homologous recombination requires the presence of an identical or

nearly identical sequence to be used as a template for repair of the

break. The enzymatic machinery responsible for this repair process is

nearly identical to the machinery responsible for

chromosomal crossover during meiosis. This pathway allows a damaged chromosome to be repaired using a sister

chromatid (available in G2 after DNA replication) or a

homologous chromosome

as a template. DSBs caused by the replication machinery attempting to

synthesize across a single-strand break or unrepaired lesion cause

collapse of the

replication fork and are typically repaired by recombination.

MMEJ starts with short-range

end resection by

MRE11 nuclease on either side of a double-strand break to reveal microhomology regions. In further steps,

Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) is required and may be an early step in MMEJ. There is pairing of microhomology regions followed by recruitment of

flap structure-specific endonuclease 1 (FEN1) to remove overhanging flaps. This is followed by recruitment of

XRCC1–

LIG3

to the site for ligating the DNA ends, leading to an intact DNA. MMEJ

is always accompanied by a deletion, so that MMEJ is a mutagenic pathway

for DNA repair.

Topoisomerases introduce both single- and double-strand breaks in the course of changing the DNA's state of

supercoiling,

which is especially common in regions near an open replication fork.

Such breaks are not considered DNA damage because they are a natural

intermediate in the topoisomerase biochemical mechanism and are

immediately repaired by the enzymes that created them.

Translesion synthesis

Translesion synthesis (TLS) is a DNA damage tolerance process that allows the

DNA replication machinery to replicate past DNA lesions such as

thymine dimers or

AP sites. It involves switching out regular

DNA polymerases

for specialized translesion polymerases (i.e. DNA polymerase IV or V,

from the Y Polymerase family), often with larger active sites that can

facilitate the insertion of bases opposite damaged nucleotides. The

polymerase switching is thought to be mediated by, among other factors,

the post-translational modification of the replication

processivity factor

PCNA.

Translesion synthesis polymerases often have low fidelity (high

propensity to insert wrong bases) on undamaged templates relative to

regular polymerases. However, many are extremely efficient at inserting

correct bases opposite specific types of damage. For example,

Pol η mediates error-free bypass of lesions induced by

UV irradiation, whereas

Pol ι introduces mutations at these sites. Pol η is known to add the first adenine across the

T^T photodimer using

Watson-Crick base pairing and the second adenine will be added in its syn conformation using

Hoogsteen base pairing. From a cellular perspective, risking the introduction of

point mutations

during translesion synthesis may be preferable to resorting to more

drastic mechanisms of DNA repair, which may cause gross chromosomal

aberrations or cell death. In short, the process involves specialized

polymerases

either bypassing or repairing lesions at locations of stalled DNA

replication. For example, Human DNA polymerase eta can bypass complex

DNA lesions like guanine-thymine intra-strand crosslink, G[8,5-Me]T,

although it can cause targeted and semi-targeted mutations. Paromita Raychaudhury and Ashis Basu studied the toxicity and mutagenesis of the same lesion in

Escherichia coli by replicating a G[8,5-Me]T-modified plasmid in

E. coli

with specific DNA polymerase knockouts. Viability was very low in a

strain lacking pol II, pol IV, and pol V, the three SOS-inducible DNA

polymerases, indicating that translesion synthesis is conducted

primarily by these specialized DNA polymerases.

A bypass platform is provided to these polymerases by

Proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA). Under normal circumstances, PCNA bound to polymerases replicates the DNA. At a site of

lesion, PCNA is ubiquitinated, or modified, by the RAD6/

RAD18 proteins to provide a platform for the specialized polymerases to bypass the lesion and resume DNA replication.

After translesion synthesis, extension is required. This extension can

be carried out by a replicative polymerase if the TLS is error-free, as

in the case of Pol η, yet if TLS results in a mismatch, a specialized

polymerase is needed to extend it;

Pol ζ.

Pol ζ is unique in that it can extend terminal mismatches, whereas more

processive polymerases cannot. So when a lesion is encountered, the

replication fork will stall, PCNA will switch from a processive

polymerase to a TLS polymerase such as Pol ι to fix the lesion, then

PCNA may switch to Pol ζ to extend the mismatch, and last PCNA will

switch to the processive polymerase to continue replication.

Global response to DNA damage

Cells exposed to

ionizing radiation,

ultraviolet light

or chemicals are prone to acquire multiple sites of bulky DNA lesions

and double-strand breaks. Moreover, DNA damaging agents can damage other

biomolecules such as

proteins,

carbohydrates,

lipids, and

RNA. The accumulation of damage, to be specific, double-strand breaks or adducts stalling the

replication forks, are among known stimulation signals for a global response to DNA damage.

The global response to damage is an act directed toward the cells' own

preservation and triggers multiple pathways of macromolecular repair,

lesion bypass, tolerance, or

apoptosis. The common features of global response are induction of multiple

genes,

cell cycle arrest, and inhibition of

cell division.

Initial steps

The packaging of eukaryotic DNA into

chromatin

presents a barrier to all DNA-based processes that require recruitment

of enzymes to their sites of action. To allow DNA repair, the chromatin

must be

remodeled. In eukaryotes,

ATP dependent

chromatin remodeling complexes and

histone-modifying enzymes are two predominant factors employed to accomplish this remodeling process.

Chromatin relaxation occurs rapidly at the site of a DNA damage. In one of the earliest steps, the stress-activated protein kinase,

c-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), phosphorylates

SIRT6 on serine 10 in response to double-strand breaks or other DNA damage. This

post-translational modification

facilitates the mobilization of SIRT6 to DNA damage sites, and is

required for efficient recruitment of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1

(PARP1) to DNA break sites and for efficient repair of DSBs.

PARP1

protein starts to appear at DNA damage sites in less than a second,

with half maximum accumulation within 1.6 seconds after the damage

occurs. PARP1 synthesizes

polymeric adenosine diphosphate ribose (poly (ADP-ribose) or PAR) chains on itself. Next the chromatin remodeler

ALC1

quickly attaches to the product of PARP1 action, a poly-ADP ribose

chain, and ALC1 completes arrival at the DNA damage within 10 seconds of

the occurrence of the damage. About half of the maximum chromatin relaxation, presumably due to action of ALC1, occurs by 10 seconds. This then allows recruitment of the DNA repair enzyme

MRE11, to initiate DNA repair, within 13 seconds.

γH2AX, the phosphorylated form of

H2AX is also involved in the early steps leading to chromatin decondensation after DNA double-strand breaks. The

histone variant H2AX constitutes about 10% of the H2A histones in human chromatin.

γH2AX (H2AX phosphorylated on serine 139) can be detected as soon as

20 seconds after irradiation of cells (with DNA double-strand break

formation), and half maximum accumulation of γH2AX occurs in one minute. The extent of chromatin with phosphorylated γH2AX is about two million base pairs at the site of a DNA double-strand break. γH2AX does not, itself, cause chromatin decondensation, but within 30 seconds of irradiation,

RNF8 protein can be detected in association with γH2AX. RNF8 mediates extensive chromatin decondensation, through its subsequent interaction with

CHD4, a component of the nucleosome remodeling and deacetylase complex

NuRD.

DDB2 occurs in a heterodimeric complex with

DDB1. This complex further complexes with the

ubiquitin ligase protein

CUL4A and with

PARP1.

This larger complex rapidly associates with UV-induced damage within

chromatin, with half-maximum association completed in 40 seconds. The PARP1 protein, attached to both DDB1 and DDB2, then

PARylates (creates a poly-ADP ribose chain) on DDB2 that attracts the DNA remodeling protein

ALC1. Action of ALC1 relaxes the chromatin at the site of UV damage to DNA. This relaxation allows other proteins in the

nucleotide excision repair pathway to enter the chromatin and repair UV-induced

cyclobutane pyrimidine dimer damages.

After rapid

chromatin remodeling,

cell cycle checkpoints are activated to allow DNA repair to occur before the cell cycle progresses. First, two

kinases,

ATM and

ATR

are activated within 5 or 6 minutes after DNA is damaged. This is

followed by phosphorylation of the cell cycle checkpoint protein

Chk1, initiating its function, about 10 minutes after DNA is damaged.

DNA damage checkpoints

After DNA damage,

cell cycle checkpoints

are activated. Checkpoint activation pauses the cell cycle and gives

the cell time to repair the damage before continuing to divide. DNA

damage checkpoints occur at the

G1/

S and

G2/

M boundaries. An intra-

S checkpoint also exists. Checkpoint activation is controlled by two master

kinases,

ATM and

ATR. ATM responds to DNA double-strand breaks and disruptions in chromatin structure, whereas ATR primarily responds to stalled

replication forks. These kinases

phosphorylate downstream targets in a

signal transduction cascade, eventually leading to cell cycle arrest. A class of checkpoint mediator proteins including

BRCA1,

MDC1, and

53BP1 has also been identified. These proteins seem to be required for transmitting the checkpoint activation signal to downstream proteins.

DNA damage checkpoint is a

signal transduction pathway that blocks

cell cycle progression in G1, G2 and

metaphase and slows down the rate of S phase progression when

DNA is damaged. It leads to a pause in cell cycle allowing the cell time to repair the damage before continuing to divide.

Checkpoint Proteins can be separated into four groups:

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-like

protein kinase,

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

(PCNA)-like group, two serine/threonine(S/T) kinases and their

adaptors. Central to all DNA damage induced checkpoints responses is a

pair of large protein kinases belonging to the first group of PI3K-like

protein kinases-the ATM (

Ataxia telangiectasia mutated)

and ATR (Ataxia- and Rad-related) kinases, whose sequence and functions

have been well conserved in evolution. All DNA damage response requires

either ATM or ATR because they have the ability to bind to the

chromosomes

at the site of DNA damage, together with accessory proteins that are

platforms on which DNA damage response components and DNA repair

complexes can be assembled.

The prokaryotic SOS response

The

SOS response is the changes in

gene expression in

Escherichia coli and other bacteria in response to extensive DNA damage. The

prokaryotic SOS system is regulated by two key proteins:

LexA and

RecA. The LexA

homodimer is a

transcriptional repressor that binds to

operator sequences commonly referred to as SOS boxes. In

Escherichia coli it is known that LexA regulates transcription of approximately 48 genes including the lexA and recA genes. The SOS response is known to be widespread in the Bacteria domain, but it is mostly absent in some bacterial phyla, like the

Spirochetes.

The most common cellular signals activating the SOS response are regions of single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), arising from stalled

replication forks or double-strand breaks, which are processed by

DNA helicase to separate the two DNA strands. In the initiation step, RecA protein binds to ssDNA in an

ATP hydrolysis driven reaction creating RecA–ssDNA filaments. RecA–ssDNA filaments activate LexA auto

protease

activity, which ultimately leads to cleavage of LexA dimer and

subsequent LexA degradation. The loss of LexA repressor induces

transcription of the SOS genes and allows for further signal induction,

inhibition of cell division and an increase in levels of proteins

responsible for damage processing.

In

Escherichia coli, SOS boxes are 20-nucleotide long sequences near promoters with

palindromic

structure and a high degree of sequence conservation. In other classes

and phyla, the sequence of SOS boxes varies considerably, with different

length and composition, but it is always highly conserved and one of

the strongest short signals in the genome.

The high information content of SOS boxes permits differential binding

of LexA to different promoters and allows for timing of the SOS

response. The lesion repair genes are induced at the beginning of SOS

response. The error-prone translesion polymerases, for example, UmuCD'2

(also called DNA polymerase V), are induced later on as a last resort.

Once the DNA damage is repaired or bypassed using polymerases or

through recombination, the amount of single-stranded DNA in cells is

decreased, lowering the amounts of RecA filaments decreases cleavage

activity of LexA homodimer, which then binds to the SOS boxes near

promoters and restores normal gene expression.

Eukaryotic transcriptional responses to DNA damage

Eukaryotic

cells exposed to DNA damaging agents also activate important defensive

pathways by inducing multiple proteins involved in DNA repair,

cell cycle checkpoint

control, protein trafficking and degradation. Such genome wide

transcriptional response is very complex and tightly regulated, thus

allowing coordinated global response to damage. Exposure of

yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae to DNA damaging agents results in overlapping but distinct transcriptional profiles. Similarities to environmental

shock response

indicates that a general global stress response pathway exist at the

level of transcriptional activation. In contrast, different human cell

types respond to damage differently indicating an absence of a common

global response. The probable explanation for this difference between

yeast and human cells may be in the

heterogeneity of

mammalian

cells. In an animal different types of cells are distributed among

different organs that have evolved different sensitivities to DNA

damage.

In general global response to DNA damage involves expression of multiple genes responsible for

postreplication repair, homologous recombination, nucleotide excision repair,

DNA damage checkpoint,

global transcriptional activation, genes controlling mRNA decay, and

many others. A large amount of damage to a cell leaves it with an

important decision: undergo apoptosis and die, or survive at the cost of

living with a modified genome. An increase in tolerance to damage can

lead to an increased rate of survival that will allow a greater

accumulation of mutations. Yeast Rev1 and human polymerase η are members

of [Y family translesion DNA

polymerases

present during global response to DNA damage and are responsible for

enhanced mutagenesis during a global response to DNA damage in

eukaryotes.

Aging

Pathological effects of poor DNA repair

DNA repair rate is an important determinant of cell pathology

Experimental animals with genetic deficiencies in DNA repair often show decreased life span and increased cancer incidence. For example, mice deficient in the dominant NHEJ pathway and in telomere maintenance mechanisms get

lymphoma and infections more often, and, as a consequence, have shorter lifespans than wild-type mice.

In similar manner, mice deficient in a key repair and transcription

protein that unwinds DNA helices have premature onset of aging-related

diseases and consequent shortening of lifespan.

However, not every DNA repair deficiency creates exactly the predicted

effects; mice deficient in the NER pathway exhibited shortened life span

without correspondingly higher rates of mutation.

If the rate of DNA damage exceeds the capacity of the cell to

repair it, the accumulation of errors can overwhelm the cell and result

in early senescence, apoptosis, or cancer. Inherited diseases associated

with faulty DNA repair functioning result in premature aging, increased sensitivity to carcinogens, and correspondingly increased cancer risk (see

below). On the other hand, organisms with enhanced DNA repair systems, such as

Deinococcus radiodurans, the most radiation-resistant known organism, exhibit remarkable resistance to the double-strand break-inducing effects of

radioactivity, likely due to enhanced efficiency of DNA repair and especially NHEJ.

Longevity and caloric restriction

Most life span influencing genes affect the rate of DNA damage

A number of individual genes have been identified as influencing

variations in life span within a population of organisms. The effects of

these genes is strongly dependent on the environment, in particular, on

the organism's diet.

Caloric restriction reproducibly results in extended lifespan in a variety of organisms, likely via

nutrient sensing pathways and decreased

metabolic rate. The molecular mechanisms by which such restriction results in lengthened lifespan are as yet unclear; however, the behavior of many genes known to be

involved in DNA repair is altered under conditions of caloric

restriction. Several agents reported to have anti-aging properties have

been shown to attenuate constitutive level of

mTOR signaling, an evidence of reduction of

metabolic activity, and concurrently to reduce constitutive level of

DNA damage induced by endogenously generated reactive oxygen species.

For example, increasing the

gene dosage of the gene SIR-2, which regulates DNA packaging in the nematode worm

Caenorhabditis elegans, can significantly extend lifespan.

The mammalian homolog of SIR-2 is known to induce downstream DNA repair

factors involved in NHEJ, an activity that is especially promoted under

conditions of caloric restriction. Caloric restriction has been closely linked to the rate of base excision repair in the nuclear DNA of rodents, although similar effects have not been observed in mitochondrial DNA.

The

C. elegans gene AGE-1, an upstream effector of DNA

repair pathways, confers dramatically extended life span under

free-feeding conditions but leads to a decrease in reproductive fitness

under conditions of caloric restriction. This observation supports the

pleiotropy theory of the

biological origins of aging,

which suggests that genes conferring a large survival advantage early

in life will be selected for even if they carry a corresponding

disadvantage late in life.

Medicine and DNA repair modulation

Hereditary DNA repair disorders

Defects in the NER mechanism are responsible for several genetic disorders, including:

Mental retardation often accompanies the latter two disorders, suggesting increased vulnerability of developmental neurons.

Other DNA repair disorders include:

All of the above diseases are often called "segmental

progerias" ("

accelerated aging diseases")

because their victims appear elderly and suffer from aging-related

diseases at an abnormally young age, while not manifesting all the

symptoms of old age.

Cancer

Because

of inherent limitations in the DNA repair mechanisms, if humans lived

long enough, they would all eventually develop cancer. There are at least 34

Inherited human DNA repair gene mutations that increase cancer risk. Many of these mutations cause DNA repair to be less effective than normal. In particular,

Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) is strongly associated with specific mutations in the DNA mismatch repair pathway.

BRCA1 and

BRCA2, two important genes whose mutations confer a hugely increased risk of breast cancer on carriers, are both associated with a large number of DNA repair pathways, especially NHEJ and homologous recombination.

Cancer therapy procedures such as

chemotherapy and

radiotherapy

work by overwhelming the capacity of the cell to repair DNA damage,

resulting in cell death. Cells that are most rapidly dividing – most

typically cancer cells – are preferentially affected. The side-effect is

that other non-cancerous but rapidly dividing cells such as progenitor

cells in the gut, skin, and hematopoietic system are also affected.

Modern cancer treatments attempt to localize the DNA damage to cells and

tissues only associated with cancer, either by physical means

(concentrating the therapeutic agent in the region of the tumor) or by

biochemical means (exploiting a feature unique to cancer cells in the

body). In the context of therapies targeting DNA damage response genes,

the latter approach has been termed 'synthetic lethality'.

Perhaps the most well-known of these 'synthetic lethality' drugs is the poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (

PARP1) inhibitor

olaparib,

which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2015 for the

treatment in women of BRCA-defective ovarian cancer. Tumor cells with

partial loss of DNA damage response (specifically,

homologous recombination

repair) are dependent on another mechanism – single-strand break repair

– which is a mechanism consisting, in part, of the PARP1 gene product.

Olaparib

is combined with chemotherapeutics to inhibit single-strand break

repair induced by DNA damage caused by the co-administered chemotherapy.

Tumor cells relying on this residual DNA repair mechanism are unable to

repair the damage and hence are not able to survive and proliferate,

whereas normal cells can repair the damage with the functioning

homologous recombination mechanism.

Many other drugs for use against other residual DNA repair

mechanisms commonly found in cancer are currently under investigation.

However, synthetic lethality therapeutic approaches have been questioned

due to emerging evidence of acquired resistance, achieved through

rewiring of DNA damage response pathways and reversion of

previously-inhibited defects.

DNA repair defects in cancer

It

has become apparent over the past several years that the DNA damage

response acts as a barrier to the malignant transformation of

preneoplastic cells. Previous studies have shown an elevated DNA damage response in cell-culture models with oncogene activation and preneoplastic colon adenomas.

DNA damage response mechanisms trigger cell-cycle arrest, and attempt

to repair DNA lesions or promote cell death/senescence if repair is not

possible. Replication stress is observed in preneoplastic cells due to

increased proliferation signals from oncogenic mutations.

Replication stress

is characterized by: increased replication initiation/origin firing;

increased transcription and collisions of transcription-replication

complexes; nucleotide deficiency; increase in reactive oxygen species

(ROS).

Replication stress, along with the selection for inactivating

mutations in DNA damage response genes in the evolution of the tumor,

leads to downregulation and/or loss of some DNA damage response

mechanisms, and hence loss of DNA repair and/or senescence/programmed

cell death. In experimental mouse models, loss of DNA damage

response-mediated cell senescence was observed after using a

short hairpin RNA (shRNA) to inhibit the double-strand break response kinase ataxia telangiectasia (

ATM), leading to increased tumor size and invasiveness. Humans born with inherited defects in DNA repair mechanisms (for example,

Li-Fraumeni syndrome) have a higher cancer risk.

The prevalence of DNA damage response mutations differs across

cancer types; for example, 30% of breast invasive carcinomas have

mutations in genes involved in homologous recombination.

In cancer, downregulation is observed across all DNA damage response

mechanisms (base excision repair (BER), nucleotide excision repair

(NER), DNA mismatch repair (MMR), homologous recombination repair (HR),

non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) and translesion DNA synthesis (TLS). As well as mutations to DNA damage repair genes, mutations also arise in the genes responsible for arresting the

cell cycle

to allow sufficient time for DNA repair to occur, and some genes are

involved in both DNA damage repair and cell cycle checkpoint control,

for example ATM and checkpoint kinase 2 (CHEK2) – a tumor suppressor

that is often absent or downregulated in non-small cell lung cancer.

|

HR |

NHEJ |

SSA |

FA |

BER |

NER |

MMR

|

|---|

| ATM |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

| ATR |

x |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

| PAXIP |

x |

x |

|

|

|

|

|

| RPA |

x |

|

x |

|

|

x |

|

| BRCA1 |

x |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

| BRCA2 |

x |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

| RAD51 |

x |

|

|

x |

|

|

|

| RFC |

x |

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| XRCC1 |

|

|

|

|

x |

x |

|

| PCNA |

|

|

|

|

x |

x |

x

|

| PARP1 |

|

x |

|

|

x |

|

|

| ERCC1 |

x |

|

x |

x |

|

x |

|

| MSH3 |

x |

|

x |

|

|

|

x

|

Table: Genes involved in DNA damage response pathways and frequently

mutated in cancer (HR = homologous recombination; NHEJ = non-homologous

end joining; SSA = single-strand annealing; FA = fanconi anemia pathway;

BER = base excision repair; NER = nucleotide excision repair; MMR =

mismatch repair)

Epigenetic DNA repair defects in cancer

Classically,

cancer has been viewed as a set of diseases that are driven by

progressive genetic abnormalities that include mutations in

tumour-suppressor genes and oncogenes, and chromosomal aberrations.

However, it has become apparent that cancer is also driven by

epigenetic alterations.

Epigenetic alterations refer to functionally relevant

modifications to the genome that do not involve a change in the

nucleotide sequence. Examples of such modifications are changes in

DNA methylation (hypermethylation and hypomethylation) and

histone modification, changes in chromosomal architecture (caused by inappropriate expression of proteins such as

HMGA2 or

HMGA1) and changes caused by

microRNAs. Each of these epigenetic alterations serves to regulate gene expression without altering the underlying

DNA sequence. These changes usually remain through

cell divisions, last for multiple cell generations, and can be considered to be epimutations (equivalent to mutations).

While large numbers of epigenetic alterations are found in

cancers, the epigenetic alterations in DNA repair genes, causing reduced

expression of DNA repair proteins, appear to be particularly important.

Such alterations are thought to occur early in progression to cancer

and to be a likely cause of the

genetic instability characteristic of cancers.

Reduced expression of DNA repair genes causes deficient DNA

repair. When DNA repair is deficient DNA damages remain in cells at a

higher than usual level and these excess damages cause increased

frequencies of mutation or epimutation. Mutation rates increase

substantially in cells defective in

DNA mismatch repair or in

homologous recombinational repair (HRR). Chromosomal rearrangements and aneuploidy also increase in HRR defective cells.

Higher levels of DNA damage not only cause increased mutation,

but also cause increased epimutation. During repair of DNA double strand

breaks, or repair of other DNA damages, incompletely cleared sites of

repair can cause epigenetic gene silencing.

Deficient expression of DNA repair proteins due to an inherited

mutation can cause increased risk of cancer. Individuals with an

inherited impairment in any of 34 DNA repair genes have an increased risk of cancer, with some defects causing up to a 100% lifetime chance of cancer (e.g. p53 mutations).

However, such germline mutations (which cause highly penetrant cancer

syndromes) are the cause of only about 1 percent of cancers.

Frequencies of epimutations in DNA repair genes

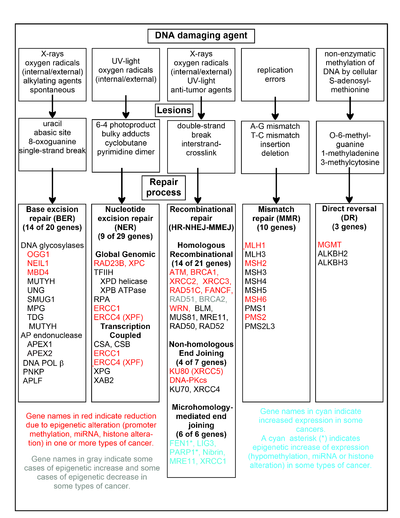

A

chart of common DNA damaging agents, examples of lesions they cause in

DNA, and pathways used to repair these lesions. Also shown are many of

the genes in these pathways, an indication of which genes are

epigenetically regulated to have reduced (or increased) expression in

various cancers. It also shows genes in the error prone

microhomology-mediated end joining pathway with increased expression in

various cancers.

Deficiencies in DNA repair enzymes are occasionally caused by a newly

arising somatic mutation in a DNA repair gene, but are much more

frequently caused by epigenetic alterations that reduce or silence

expression of DNA repair genes. For example, when 113 colorectal cancers

were examined in sequence, only four had a

missense mutation in the DNA repair gene

MGMT, while the majority had reduced MGMT expression due to methylation of the MGMT promoter region (an epigenetic alteration).

Five different studies found that between 40% and 90% of colorectal

cancers have reduced MGMT expression due to methylation of the MGMT

promoter region.

Similarly, out of 119 cases of mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancers that lacked DNA repair gene

PMS2

expression, PMS2 was deficient in 6 due to mutations in the PMS2 gene,

while in 103 cases PMS2 expression was deficient because its pairing

partner

MLH1 was repressed due to promoter methylation (PMS2 protein is unstable in the absence of MLH1). In the other 10 cases, loss of PMS2 expression was likely due to epigenetic overexpression of the

microRNA,

miR-155, which down-regulates MLH1.

In a further example, epigenetic defects were found in various

cancers (e.g. breast, ovarian, colorectal and head and neck). Two or

three deficiencies in the expression of

ERCC1,

XPF or PMS2 occur simultaneously in the majority of 49 colon cancers evaluated by Facista et al.

The chart in this section shows some frequent DNA damaging

agents, examples of DNA lesions they cause, and the pathways that deal

with these DNA damages. At least 169 enzymes are either directly

employed in DNA repair or influence DNA repair processes. Of these, 83 are directly employed in repairing the 5 types of DNA damages illustrated in the chart.

Some of the more well studied genes central to these repair

processes are shown in the chart. The gene designations shown in red,

gray or cyan indicate genes frequently epigenetically altered in various

types of cancers. Wikipedia articles on each of the genes highlighted

by red, gray or cyan describe the epigenetic alteration(s) and the

cancer(s) in which these epimutations are found. Review articles, and broad experimental survey articles also document most of these epigenetic DNA repair deficiencies in cancers.

Red-highlighted genes are frequently reduced or silenced by

epigenetic mechanisms in various cancers. When these genes have low or

absent expression, DNA damages can accumulate. Replication errors past

these damages can lead to increased mutations and, ultimately, cancer. Epigenetic repression of DNA repair genes in

accurate DNA repair pathways appear to be central to

carcinogenesis.

The two gray-highlighted genes

RAD51 and

BRCA2, are required for

homologous recombinational

repair. They are sometimes epigenetically over-expressed and sometimes

under-expressed in certain cancers. As indicated in the Wikipedia

articles on

RAD51 and

BRCA2,

such cancers ordinarily have epigenetic deficiencies in other DNA

repair genes. These repair deficiencies would likely cause increased

unrepaired DNA damages. The over-expression of

RAD51 and

BRCA2 seen in these cancers may reflect selective pressures for compensatory

RAD51 or

BRCA2

over-expression and increased homologous recombinational repair to at

least partially deal with such excess DNA damages. In those cases where

RAD51 or

BRCA2 are under-expressed, this would itself lead to increased unrepaired DNA damages. Replication errors past these damages could cause increased mutations and cancer, so that under-expression of

RAD51 or

BRCA2 would be carcinogenic in itself.

Cyan-highlighted genes are in the

microhomology-mediated end joining (MMEJ) pathway and are up-regulated in cancer. MMEJ is an additional error-prone

inaccurate

repair pathway for double-strand breaks. In MMEJ repair of a

double-strand break, an homology of 5–25 complementary base pairs

between both paired strands is sufficient to align the strands, but

mismatched ends (flaps) are usually present. MMEJ removes the extra

nucleotides (flaps) where strands are joined, and then ligates the

strands to create an intact DNA double helix. MMEJ almost always

involves at least a small deletion, so that it is a mutagenic pathway.

FEN1,

the flap endonuclease in MMEJ, is epigenetically increased by promoter

hypomethylation and is over-expressed in the majority of cancers of the

breast, prostate, stomach, neuroblastomas, pancreas, and lung. PARP1 is also over-expressed when its promoter region

ETS site is

epigenetically hypomethylated, and this contributes to progression to endometrial cancer and BRCA-mutated serous ovarian cancer. Other genes in the

MMEJ pathway are also over-expressed in a number of cancers (see

MMEJ for summary), and are also shown in cyan.

Genome-wide distribution of DNA repair in human somatic cells

Differential

activity of DNA repair pathways across various regions of the human

genome causes mutations to be very unevenly distributed within tumor

genomes.

In particular, the gene-rich, early-replicating regions of the human

genome exhibit lower mutation frequencies than the gene-poor,

late-replicating

heterochromatin. One mechanism underlying this involves the

histone modification H3K36me3, which can recruit

mismatch repair proteins, thereby lowering mutation rates in

H3K36me3-marked regions. Another important mechanism concerns

nucleotide excision repair, which can be recruited by the transcription machinery, lowering somatic mutation rates in active genes and other open chromatin regions.

Evolution

The basic processes of DNA repair are highly

conserved among both

prokaryotes and

eukaryotes and even among

bacteriophages (

viruses which infect

bacteria); however, more complex organisms with more complex genomes have correspondingly more complex repair mechanisms. The ability of a large number of protein

structural motifs

to catalyze relevant chemical reactions has played a significant role

in the elaboration of repair mechanisms during evolution. For an

extremely detailed review of hypotheses relating to the evolution of DNA

repair, see.

The

fossil record indicates that single-cell life began to proliferate on the planet at some point during the

Precambrian period, although exactly when recognizably modern life first emerged is unclear.

Nucleic acids

became the sole and universal means of encoding genetic information,

requiring DNA repair mechanisms that in their basic form have been

inherited by all extant life forms from their common ancestor. The

emergence of Earth's oxygen-rich atmosphere (known as the "

oxygen catastrophe") due to

photosynthetic organisms, as well as the presence of potentially damaging

free radicals in the cell due to

oxidative phosphorylation, necessitated the evolution of DNA repair mechanisms that act specifically to counter the types of damage induced by

oxidative stress.

Rate of evolutionary change

On

some occasions, DNA damage is not repaired, or is repaired by an

error-prone mechanism that results in a change from the original

sequence. When this occurs,

mutations may propagate into the genomes of the cell's progeny. Should such an event occur in a

germ line cell that will eventually produce a

gamete, the mutation has the potential to be passed on to the organism's offspring. The rate of

evolution

in a particular species (or, in a particular gene) is a function of the

rate of mutation. As a consequence, the rate and accuracy of DNA repair

mechanisms have an influence over the process of evolutionary change.

DNA damage protection and repair does not influence the rate of

adaptation by gene regulation and by recombination and selection of

alleles. On the other hand, DNA damage repair and protection does

influence the rate of accumulation of irreparable, advantageous, code

expanding, inheritable mutations, and slows down the evolutionary

mechanism for expansion of the genome of organisms with new

functionalities. The tension between evolvability and mutation repair

and protection needs further investigation.

Technology

A technology named clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (shortened to

CRISPR-Cas9)

was discovered in 2012. The new technology allows anyone with

molecular biology training to alter the genes of any species with

precision, by inducing DNA damage at a specific point and then altering

DNA repair mechanisms to insert new genes.

It is cheaper, more efficient, and more precise than other

technologies. With the help of CRISPR–Cas9, parts of a genome can be

edited by scientists by removing, adding, or altering parts in a DNA

sequence.