From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Adultery (from Latin adulterium) is extramarital sex that is considered objectionable on social, religious, moral, or legal grounds. Although the sexual activities

that constitute adultery vary, as well as the social, religious, and

legal consequences, the concept exists in many cultures and is similar

in Christianity, Islam, and Judaism.

A single act of sexual intercourse is generally sufficient to

constitute adultery, and a more long-term sexual relationship is

sometimes referred to as an affair.

Historically, many cultures considered adultery a very serious crime, some subject to severe punishment, usually for the woman and sometimes for the man, with penalties including capital punishment, mutilation, or torture. Such punishments have gradually fallen into disfavor, especially in Western countries from the 19th century. In countries where adultery is still a criminal offense, punishments range from fines to caning

and even capital punishment. Since the 20th century, criminal laws

against adultery have become controversial, with most Western countries

decriminalising adultery.

However, even in jurisdictions that have decriminalised adultery,

it may still have legal consequences, particularly in jurisdictions

with fault-based divorce laws, where adultery almost always constitutes a ground for divorce and may be a factor in property settlement, the custody of children, the denial of alimony, etc. Adultery is not a ground for divorce in jurisdictions which have adopted a no-fault divorce model.

International organizations have called for the decriminalisation of adultery, especially in the light of several high-profile stoning

cases that have occurred in some countries. The head of the United

Nations expert body charged with identifying ways to eliminate laws that

discriminate against women or are discriminatory to them in terms of

implementation or impact, Kamala Chandrakirana, has stated that: "Adultery must not be classified as a criminal offence at all".

A joint statement by the United Nations Working Group on discrimination

against women in law and in practice states that: "Adultery as a

criminal offence violates women’s human rights".

In Muslim countries that follow Sharia law for criminal justice, the punishment for adultery may be stoning. There are fifteen

countries in which stoning is authorized as lawful punishment, though

in recent times it has been legally carried out only in Iran and

Somalia. Most countries that criminalize adultery are those where the dominant religion is Islam, and several Sub-Saharan African

Christian-majority countries, but there are some notable exceptions to

this rule, namely Philippines, and several U.S. states. In some

jurisdictions, having sexual relations with the king's wife or the wife

of his eldest son constitutes treason.

Overview

Public punishment of adulterers in Venice, 17th century

The term adultery refers to sexual acts between a married person and someone who is not that person's spouse. It may arise in a number of contexts. In criminal law, adultery was a criminal offence in many countries in the past, and is still a crime in some countries today. In family law, adultery may be a ground for divorce, with the legal definition of adultery being "physical contact with an alien and unlawful organ",

while in some countries today, adultery is not in itself grounds for

divorce. Extramarital sexual acts not fitting this definition are not

"adultery" though they may constitute "unreasonable behavior", also a

ground of divorce.

Another issue is the issue of paternity of a child. The

application of the term to the act appears to arise from the idea that

"criminal intercourse with a married woman ... tended to adulterate the

issue [children] of an innocent husband ... and to expose him to support

and provide for another man's [children]". Thus, the "purity" of the children of a marriage is corrupted, and the inheritance is altered.

Some adultery laws differentiate based on the sex of the

participants, and as a result such laws are often seen as

discriminatory, and in some jurisdictions they have been struck down by

courts, usually on the basis that they discriminated against women.

The term adultery, rather than extramarital sex,

implies a moral condemnation of the act; as such it is usually not a

neutral term because it carries an implied judgment that the act is

wrong.

Adultery refers to sexual relations which are not officially

legitimized; for example it does not refer to having sexual intercourse

with multiple partners in the case of polygamy (when a man is married to more than one wife at a time, called polygyny; or when a woman is married to more than one husband at a time, called polyandry).

Tort of criminal conversation

In archaic law, there was a common law tort of criminal conversation

arising from adultery, "conversation" being an archaic euphemism for

sexual intercourse. It was a tort action brought by a husband against a

third party (“the other man”) who interfered with the marriage

relationship. This tort has been abolished in almost all jurisdictions,

but continues to apply, for example, in some states in the United States, most notably in North Carolina.

Defence of provocation

Marital infidelity has been used, especially in the past, as a legal defence of provocation to a criminal charge, such as murder or assault. In some jurisdictions, the defence of provocation has been replaced by a partial defence or provocation or the behaviour of the victim can be invoked as a mitigating factor in sentencing.

Definitions and legal constructs

Anne Boleyn

was found guilty of adultery and treason and executed in 1536. There is

controversy among historians as to whether she had actually committed

adultery.

Le supplice des adultères, by Jules Arsène Garnier, showing two adulterers being punished

In the traditional English common law, adultery was a felony. Although the legal definition of adultery differs in nearly every legal system, the common theme is sexual relations outside of marriage, in one form or another.

Traditionally, many cultures, particularly Latin American ones, had strong double standards regarding male and female adultery, with the latter being seen as a much more serious violation.

Adultery involving a married woman and a man other than her

husband was considered a very serious crime. In 1707, English Lord Chief

Justice John Holt stated that a man having sexual relations with

another man's wife was "the highest invasion of property" and claimed,

in regard to the aggrieved husband, that "a man cannot receive a higher

provocation" (in a case of murder or manslaughter).

The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert, Vol. 1 (1751), also equated adultery to theft

writing that, "adultery is, after homicide, the most punishable of all

crimes, because it is the most cruel of all thefts, and an outrage

capable of inciting murders and the most deplorable excesses."

Legal definitions of adultery vary. For example, New York defines an adulterer as a person who "engages in sexual intercourse with another person at a time when he has a living spouse, or the other person has a living spouse."

North Carolina defines adultery as occurring when any man and woman "lewdly and lasciviously associate, bed, and cohabit together."

Minnesota

law provides: "when a married woman has sexual intercourse with a man

other than her husband, whether married or not, both are guilty of

adultery." In the 2003 New Hampshire Supreme Court case Blanchflower v. Blanchflower, it was held that female same-sex sexual relations did not constitute sexual intercourse, based on a 1961 definition from Webster's Third New International Dictionary; and thereby an accused wife in a divorce case was found not guilty of adultery. In 2001, Virginia prosecuted an attorney, John R. Bushey, for adultery, a case that ended in a guilty plea and a $125 fine. Adultery is against the governing law of the U.S. military.

In common-law countries, adultery was also known as criminal conversation. This became the name of the civil tort arising from adultery, being based upon compensation for the other spouse's injury. Criminal conversation was usually referred to by lawyers as crim. con., and was abolished in England in 1857, and the Republic of Ireland in 1976. Another tort, alienation of affection, arises when one spouse deserts the other for a third person. This act was also known as desertion, which was often a crime as well. A small number of jurisdictions still allow suits for criminal conversation and/or alienation of affection. In the United States, six states still maintain this tort.

A marriage in which both spouses agree ahead of time to accept

sexual relations by either partner with others is sometimes referred to

as an open marriage or the swinging lifestyle. Polyamory,

meaning the practice, desire, or acceptance of intimate relationships

that are not exclusive with respect to other sexual or intimate

relationships, with knowledge and consent of everyone involved,

sometimes involves such marriages. Swinging and open marriages are both a

form of non-monogamy,

and the spouses would not view the sexual relations as objectionable.

However, irrespective of the stated views of the partners, extra-marital

relations could still be considered a crime in some legal jurisdictions

which criminalize adultery.

In Canada, though the written definition in the Divorce Act refers to extramarital relations with someone of the opposite sex, a British Columbia judge used the Civil Marriage Act

in a 2005 case to grant a woman a divorce from her husband who had

cheated on her with another man, which the judge felt was equal

reasoning to dissolve the union.

In the United Kingdom, case law restricts the definition of

adultery to penetrative sexual intercourse between a man and a woman, no

matter the gender of the spouses in the marriage, although infidelity

with a person of the same gender can be grounds for a divorce as

unreasonable behavior; this situation was discussed at length during

debates on the Marriage (Same-Sex Couples) Bill.

In India, adultery

is the sexual intercourse of a man with a married woman without the

consent of her husband when such sexual intercourse does not amount to

rape. It was a non-cognizable, non-bailable criminal offence, until the

relevant law was overturned by the Supreme Court of India on 27

September 2018.

Punishment

In jurisdictions where adultery is illegal, punishments vary from fines (for example in the US state of Rhode Island) to caning in parts of Asia. In fifteen countries the punishment includes stoning, although in recent times it has been legally enforced only in Iran and Somalia. Most stoning cases are the result of mob violence,

and while technically illegal, no action is usually taken against

perpetrators. Sometimes such stonings are ordered by informal village

leaders who have de facto power in the community. Adultery may have consequences under civil law even in countries where it is not outlawed by the criminal law. For instance it may constitute fault in countries where the divorce law is fault based or it may be a ground for tort.

In some jurisdictions, the "intruder" (the third party) is

punished, rather than the adulterous spouse. For instance art 266 of the

Penal Code of South Sudan reads: "Whoever, has consensual sexual

intercourse with a man or woman who is and whom he or she has reason

to believe to be the spouse of another person, commits the offence of

adultery [...]". Similarly, under the adultery law in India

(Section 497 of the Indian Penal Code, until overturned by the Supreme

Court in 2018) it was a criminal offense for a man to have consensual

sexual intercourse with a married woman, without the consent of her

husband (no party was criminally punished in case of adultery between a

married man and an unmarried woman).

Legal issues regarding paternity

Historically, paternity of children born out of adultery has been seen as a major issue. Modern advances such as reliable contraception and paternity testing

have changed the situation (in Western countries). Most countries

nevertheless have a legal presumption that a woman's husband is the

father of her children who were born during that marriage. Although this

is often merely a rebuttable presumption,

many jurisdictions have laws which restrict the possibility of legal

rebuttal (for instance by creating a legal time limit during which

paternity may be challenged – such as a certain number of years from the

birth of the child). Establishing correct paternity may have major legal implications, for instance in regard to inheritance.

Children born out of adultery suffered, until recently, adverse legal and social consequences. In France,

for instance, a law that stated that the inheritance rights of a child

born under such circumstances were, on the part of the married parent,

half of what they would have been under ordinary circumstances, remained

in force until 2001, when France was forced to change it by a ruling of

the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) (and in 2013, the ECtHR also ruled that the new 2001 regulations must be also applied to children born before 2001).

There has been, in recent years, a trend of legally favoring the

right to a relation between the child and its biological father, rather

than preserving the appearances of the 'social' family. In 2010, the

ECtHR ruled in favor of a German man who had fathered twins with a

married woman, granting him right of contact with the twins, despite the

fact that the mother and her husband had forbidden him from seeing the

children.

Prevalence

Durex's Global Sex Survey found that worldwide 22% of people surveyed admitted to have had extramarital sex.

In the United States Alfred Kinsey found in his studies that 50% of males and 26% of females had extramarital sex at least once during their lifetime. Depending on studies, it was estimated that 22.7% of men and 11.6% of women, had extramarital sex. Other authors say that between 20% and 25% of Americans had sex with someone other than their spouse.

Three 1990s studies in the United States, using nationally

representative samples, have found that about 10–15% of women and 20–25%

of men admitted to having engaged in extramarital sex.

The Standard Cross-Cultural Sample

described the occurrence of extramarital sex by gender in over 50

pre-industrial cultures. The occurrence of extramarital sex by men is

described as "universal" in 6 cultures, "moderate" in 29 cultures,

"occasional" in 6 cultures, and "uncommon" in 10 cultures. The

occurrence of extramarital sex by women is described as "universal" in 6

cultures, "moderate" in 23 cultures, "occasional" in 9 cultures, and

"uncommon" in 15 cultures.

Cultural and religious traditions

Man and woman undergoing public exposure for adultery in Japan, around 1860

Greco-Roman world

In the Greco-Roman world, there were stringent laws against adultery, but these applied to sexual intercourse with a married woman. In the early Roman Law, the jus tori

belonged to the husband. It was therefore not a crime against the wife

for a husband to have sex with a slave or an unmarried woman.

The Roman husband often took advantage of his legal immunity. Thus we are told by the historian Spartianus that Verus, the imperial colleague of Marcus Aurelius, did not hesitate to declare to his reproaching wife: "Uxor enim dignitatis nomen est, non voluptatis." ('Wife' connotes rank, not sexual pleasure, or more literally "Wife is the name of dignity, not bliss") (Verus, V).

Later in Roman history, as William E.H. Lecky has shown, the idea

that the husband owed a fidelity similar to that demanded of the wife

must have gained ground, at least in theory. Lecky gathers from the legal maxim of Ulpian: "It seems most unfair for a man to require from a wife the chastity he does not himself practice".

According to Plutarch, the lending of wives practiced among some people was also encouraged by Lycurgus,

though from a motive other than that which actuated the practice

(Plutarch, Lycurgus, XXIX). The recognized license of the Greek husband

may be seen in the following passage of the pseudo-Demosthenic Oration Against Neaera:

- We keep mistresses for our pleasures, concubines for constant

attendance, and wives to bear us legitimate children and to be our

faithful housekeepers. Yet, because of the wrong done to the husband

only, the Athenian lawgiver Solon allowed any man to kill an adulterer

whom he had taken in the act. (Plutarch, Solon)

The Roman Lex Julia, Lex Iulia de Adulteriis Coercendis (17 BC), punished adultery with banishment. The two guilty parties were sent to different islands ("dummodo in diversas insulas relegentur"), and part of their property was confiscated.

Fathers were permitted to kill daughters and their partners in

adultery. Husbands could kill the partners under certain circumstances

and were required to divorce adulterous wives.

Abrahamic religions

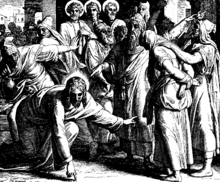

Biblical sources

Both Judaism and Christianity base their attitudes to adultery on passages in the Hebrew Bible (Old Testament in Christianity), which firstly prohibits adultery in the Seventh Commandment: "Thou shalt not commit adultery." (Exodus 20:12). Leviticus 20:10 subsequently prescribes capital punishment for adultery, but refers to adultery between a man and a married woman:

And the man that committeth adultery with another man's wife, even he

that committeth adultery with his neighbour's wife, the adulterer and

the adulteress shall surely be put to death.

Significantly, the biblical penalty does not apply to sex if the

woman is unmarried, otherwise it applies irrespective of the marital

status of the man. That is, if the man was married while the woman was

not, there would not be a death penalty for adultery under these

passages.

Judaism

Though

Leviticus 20:10 prescribes the death penalty for adultery, the legal

procedural requirements were very exacting and required the testimony of

two eyewitnesses of good character for conviction. The defendant also

must have been warned immediately before performing the act. A death sentence could be issued only during the period when the Holy Temple stood, and only so long as the Supreme Torah Court convened in its chamber within the Temple complex. Today, therefore, no death penalty applies.

The death penalty for adultery was strangulation,

except in the case of a woman who was the daughter of a Kohain (Aaronic

priestly caste), which was specifically mentioned by Scripture by the

death penalty of burning (pouring molten lead down the throat).

Ipso facto, there never was mentioned in Pharisaic or Rabbinic Judaism

sources a punishment of stoning for adulterers as mentioned in John 8:5-7.

At the civil level, however, Jewish law

(halakha) forbids a man to continue living with an adulterous wife, and

he is obliged to divorce her. Also, an adulteress is not permitted to

marry the adulterer, but, to avoid any doubt as to her status as being

free to marry another or that of her children, many authorities say he

must give her a divorce as if they were married.

According to Judaism, the Seven laws of Noah apply to all of humankind; these laws prohibit adultery with another man's wife.

The Ten Commandments were meant exclusively for Jewish males. Michael Coogan

writes that according to the text the wives are the property of their

man, marriage meaning transfer of property (from father to husband), and women are less valuable than real estate, being mentioned after real estate. Adultery is violating the property right of a man. Coogan's book was criticized by Phyllis Trible, who argues that he failed to note that patriarchy was not decreed, but only described by God, patriarchy being specific to people after the fall. She states that Paul the Apostle made the same mistake as Coogan.

Sexual intercourse between an Israelite man, married or not, and a woman who was neither married nor betrothed was not considered adultery.

This concept of adultery stems from the economic aspect of Israelite

marriage whereby the husband has an exclusive right to his wife, whereas

the wife, as the husband's possession, did not have an exclusive right

to her husband.

David's sexual intercourse with Bathsheba, the wife of Uriah, did not count as adultery. According to Jennifer Wright Knust, this was because Uriah was no Jew, and only Jewish men were protected by the legal code from Sinai. However, according to the Babylonian Talmud, Uriah was indeed Jewish and wrote a provisional bill of divorce

prior to going out to war, specifying that if he fell in battle, the

divorce would take effect from the time the writ was issued.

Christianity

'Thou shalt not commit adultery' (Nathan confronts David); bronze bas-relief on the door of the

La Madeleine, Paris,

Paris.

Adultery is considered by Christians immoral and a sin, based primarily on passages like Exodus 20:14 and 1 Corinthians 6:9–10. Although 1 Corinthians 6:11 does say that "and that is what some of you were. But you were washed", it still acknowledges adultery to be immoral and a sin.

Catholicism ties fornication with breaking the sixth commandment in its Catechism.

Until a few decades ago, adultery was a criminal offense in many countries where the dominant religion is Christianity, especially in Roman Catholic countries (see also the section on Europe). Adultery was decriminalized in Argentina in 1995, and in Brazil in 2005; but in some predominantly Catholic countries, such as the Philippines, it remains illegal. The Book of Mormon also prohibits adultery. For instance, Abinadi cites the Ten Commandments when he accuses King Noah's priests of sexual immorality. When Jesus Christ visits the Americas he reinforces the law and teaches them the higher law (also found in the New Testament):

- Behold, it is written by them of old time, that thou shalt

not commit adultery; but I say unto you, that whosoever looketh on a

woman, to lust after her, hath committed adultery already in his heart.

Some churches such as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints have interpreted "adultery" to include all sexual relationships outside of marriage, regardless of the marital status of the participants. Book of Mormon prophets and civil leaders often list adultery as an illegal activity along with murder, robbing, and stealing.

Islam

Zina'

is an Arabic term for illegal intercourse, premarital or extramarital.

Various conditions and punishments have been attributed to adultery.

Under

Islamic law,

adultery in general is sexual intercourse by a person (whether man or

woman) with someone to whom they are not married. Adultery is a

violation of the marital contract and one of the major sins condemned by

Allah in the

Qur'an:

Qur'anic verses prohibiting adultery include:

- "Do not go near to adultery. Surely it is a shameful deed and evil, opening roads (to other evils)."[Quran 17:32]

- "Say, 'Verily, my Lord has prohibited the shameful deeds, be it

open or secret, sins and trespasses against the truth and reason.'"[Quran 7:33]

Punishments are reserved to the legal authorities and false accusations are to be punished severely. It has been said that these legal procedural requirements were instituted to protect women from slander

and false accusations: i.e. four witnesses of good character are

required for conviction, who were present at that time and saw the deed

taking place; and if they saw it they were not of good moral character,

as they were looking at naked adults; thus no one can be convicted of

adultery unless both of the accused also agree and give their confession

under oath four times.

According to ahadith

attributed to Muhammad, an unmarried person who commits adultery or

fornication is punished by flogging 100 times; a married person will

then be stoned to death. A survey conducted by the Pew Research Center found support for stoning as a punishment for adultery mostly in Arab countries; it was supported in Egypt (82% of respondents in favor of the punishment) and Jordan (70% in favor), as well as Pakistan (82% favor), whereas in Nigeria (56% in favor) and in Indonesia (42% in favor) opinion is more divided, perhaps due to diverging traditions and differing interpretations of Sharia.

Eastern religions

Hinduism

The Hindu Sanskrit texts present a range of views on adultery, offering widely differing positions. The hymn 4.5.5 of the Rigveda calls adultery as pāpa (evil, sin). Other Vedic texts state adultery to be a sin, just like murder, incest, anger, evil thoughts and trickery. The Vedic texts, including the Rigveda, the Atharvaveda and the Upanishads,

also acknowledge the existence of male lovers and female lovers as a

basic fact of human life, followed by the recommendation that one should

avoid such extra marital sex during certain ritual occasions (yajna).

A number of simile in the Rigveda, a woman's emotional eagerness to

meet her lover is described, and one hymn prays to the gods that they

protect the embryo of a pregnant wife as she sleeps with her husband and

other lovers.

Adultery and similar offenses are discussed under one of the eighteen vivādapadas (titles of laws) in the Dharma literature of Hinduism. Adultery is termed as Strisangrahana in dharmasastra texts. These texts generally condemn adultery, with some exceptions involving consensual sex and niyoga (levirate conception) in order to produce an heir. According to Apastamba Dharmasutra,

the earliest dated Hindu law text, cross-varna adultery is a punishable

crime, where the adulterous man receives a far more severe punishment

than the adulterous arya woman. In Gautama Dharmasutra, the adulterous arya woman is liable to harsh punishment for the cross-class adultery. While Gautama Dharmasutra reserves the punishment in cases of cross-class adultery, it seems to have been generalized by Vishnu Dharmasastra and Manusmiriti. The recommended punishments in the text also vary between these texts.

The Manusmriti, also known as the Laws of Manu, deals with this in greater detail. When translated, verse 4.134 of the book declares adultery to be a heinous offense. The Manusmriti does not include adultery as a "grievous sin", but includes it as a "secondary sin" that leads to a loss of caste.

In the book, the intent and mutual consent are a part that determine

the recommended punishment. Rape is not considered as adultery for the

woman, while the rapist is punished severely. Lesser punishment is

recommended for consensual adulterous sex. Death penalty is mentioned by Manu, as well as "penance" for the sin of adultery. even in cases of repeated adultery with a man of the same caste.

In verses 8.362-363, the author states that sexual relations with the

wife of traveling performer is not a sin, and exempts such sexual

liaisons.

The book offers two views on adultery. It recommends a new married

couple to remain sexually faithful to each other for life. It also

accepts that adulterous relationships happen, children are born from

such relationships and then proceeds to reason that the child belongs to

the legal husband of the pregnant woman, and not to the biological

father.

Other dharmasastra texts describe adultery as a punishable crime but offer differing details. According to Naradasmriti (12.61-62), it is an adulterous act if a man has sexual intercourse with the woman who is protected by another man. The term adultery in Naradasmriti

is not confined to the relationship of a married man with another man's

wife. It includes sex with any woman who is protected, including wives,

daughters, other relatives, and servants. Adultery is not a punishable

offence for a man if "the woman's husband has abandoned her because she

is wicked, or he is eunuch, or of a man who does not care, provided the

wife initiates it of her own volition".

Brihaspati-smriti mention, among other things, adulterous local customs

in ancient India and then states, "for such practices these (people)

incur neither penance nor secular punishment". Kautilya's Arthashastra

includes an exemption that in case the husband forgives his adulterous

wife, the woman and her lover should be set free. If the offended

husband does not forgive, the Arthashastra recommends the adulterous woman's nose and ears be cut off, while her lover be executed.

The Kamasutra discusses adultery and Vatsyayana devotes "not less than fifteen sutras (1.5.6–20) to enumerating the reasons (karana) for which a man is allowed to seduce a married woman". According to Wendy Doniger, the Kamasutra

teaches adulterous sexual liaison as a means for a man to predispose

the involved woman in assisting him, working against his enemies and

facilitating his successes. It also explains the many signs and reasons a

woman wants to enter into an adulterous relationship and when she does

not want to commit adultery. The Kamasutra

teaches strategies to engage in adulterous relationships, but concludes

its chapter on sexual liaison stating that one should not commit

adultery because adultery pleases only one of two sides in a marriage,

hurts the other, it goes against both dharma and artha.

According to Werner Menski, the Sanskrit texts take "widely

different positions on adultery", with some considering it a minor

offense that can be addressed with penance, but others treat it as a

severe offense that depending on the caste deserves the death penalty

for the man or the woman.

According to Ramanathan and Weerakoon, in Hinduism, the sexual matters

are left to the judgment of those involved and not a matter to be

imposed through law.

According to Carl Olsen, the classical Hindu society considered

adultery as a sexual transgression but treated it with a degree of

tolerance. It is described as a minor transgression in Naradasmriti and other texts, one that a sincere penance could atone.

Penance is also recommended to a married person who does not actually

commit adultery, but carries adulterous thoughts for someone else or is

thinking of committing adultery.

Other Hindu texts present a more complex model of behavior and

mythology where gods commit adultery for various reasons. For example, Krishna commits adultery and the Bhagavata Purana justifies it as something to be expected when Vishnu took a human form, just like sages become uncontrolled. According to Tracy Coleman, Radha and other gopis are indeed lovers of Krishna, but this is prema

or "selfless, true love" and not carnal craving. In Hindu texts, this

relationship between gopis and Krishna involves secret nightly

rendezvous. Some texts state it to be divine adultery, others as a

symbolism of spiritual dedication and religious value.

The example of Krishna's adulterous behavior has been used by Sahajiyas

Hindus of Bengal to justify their own behavior that is contrary to the

mainstream Hindu norm, according to Doniger.

Other Hindu texts state that Krishna's adultery is not a license for

other men to do the same, in the same way that men should not drink

poison just because Rudra-Shiva drank poison during the Samudra Manthan. A similar teaching is found in Mahayana Buddhism, states Doniger.

Buddhism

Buddhist texts such as Digha Nikāya

describe adultery as a form of sexual wrongdoing that is one link in a

chain of immorality and misery. According to Wendy Doniger, this view of

adultery as evil is postulated in early Buddhist texts as having

originated from greed in a previous life. This idea combines Hindu and Buddhist thoughts then prevalent. Sentient beings without body, state the canonical texts,

are reborn on earth due to their greed and craving, some people become

beautiful and some ugly, some become men and some women. The ugly envy

the beautiful and this triggers the ugly to commit adultery with the

wives of the beautiful. Like in Hindu mythology, states Doniger, Buddhist texts explain adultery as a result from sexual craving; it initiates a degenerative process.

Buddhism considers celibacy as the monastic ideal. For he who

feels that he cannot live in celibacy, it recommends that he never

commit adultery with another's wife.

Engaging in sex outside of marriage, with the wife of another man, with

a girl who is engaged to be married, or a girl protected by her

relatives (father or brother), or extramarital sex with prostitutes,

ultimately causes suffering to other human beings and oneself. It should

be avoided, state the Buddhist canonical texts.

Buddhist Pali texts narrate legends where the Buddha explains the

karmic consequences of adultery. For example, states Robert Goldman,

one such story is of Thera Soreyya.

Buddha states in the Soreyya story that "men who commit adultery suffer

hell for hundreds of thousands of years after rebirth, then are reborn a

hundred successive times as women on earth, must earn merit by "utter

devotion to their husbands" in these lives, before they can be reborn

again as men to pursue a monastic life and liberation from samsara.

There are some differences between the Buddhist texts and the

Hindu texts on the identification and consequences of adultery.

According to José Ignacio Cabezón, for example, the Hindu text Naradasmriti

considers consensual extra-marital sex between a man and a woman in

certain circumstances (such as if the husband has abandoned the woman)

as not a punishable crime, but the Buddhist texts "nowhere exculpate"

any adulterous relationship. The term adultery in Naradasmriti is

broader in scope than the one in Buddhist sources. In the text, various

acts such as secret meetings, exchange of messages and gifts,

"inappropriate touching" and a false accusation of adultery, are deemed

adulterous, while Buddhist texts do not recognize these acts under

adultery. Later texts such as the Dhammapada, Pancasiksanusamsa Sutra

and a few Mahayana sutras state that "heedless man who runs after other

men's wife" acquire demerit, blame, discomfort and are reborn in hell. Other Buddhist texts make no mention of legal punishments for adultery.

Other historical practices

After being accused of adultery,

Cunigunde of Luxembourg proved her innocence by walking over red-hot ploughshares.

In some Native American cultures, severe penalties could be imposed

on an adulterous wife by her husband. In many instances she was made to

endure a bodily mutilation which would, in the mind of the aggrieved

husband, prevent her from ever being a temptation to other men again. Among the Aztecs, wives caught in adultery were occasionally impaled, although the more usual punishment was to be stoned to death.

The Code of Hammurabi, a well-preserved Babylonian law code of ancient Mesopotamia, dating back to about 1772 BC, provided drowning as punishment for adultery.

Amputation of the nose – rhinotomy –

was a punishment for adultery among many civilizations, including

ancient India, ancient Egypt, among Greeks and Romans, and in Byzantium

and among the Arabs.

In the tenth century, the Arab explorer Ibn Fadlan noted that adultery was unknown among the pagan Oghuz Turks.

Ibn Fadlan writes that "adultery is unknown among them; but whomsoever

they find by his conduct that he is an adulterer, they tear him in two.

This comes about so: they bring together the branches of two trees, tie

him to the branches and then let both trees go, so that he is torn in

two."

In medieval Europe, early Jewish law mandated stoning for an adulterous wife and her partner.

In England and its successor states, it has been high treason

to engage in adultery with the King's wife, his eldest son's wife and

his eldest unmarried daughter. The jurist Sir William Blackstone writes

that "the plain intention of this law is to guard the Blood Royal from

any suspicion of bastardy, whereby the succession to the Crown might be

rendered dubious." Adultery was a serious issue when it came to

succession to the crown. Philip IV of France had all three of his daughters-in-law imprisoned, two (Margaret of Burgundy and Blanche of Burgundy) on the grounds of adultery and the third (Joan of Burgundy)

for being aware of their adulterous behaviour. The two brothers accused

of being lovers of the king's daughters-in-law were executed

immediately after being arrested. The wife of Philip IV's eldest son

bore a daughter, the future Joan II of Navarre, whose paternity and succession rights were disputed all her life.

The christianization of Europe

came to mean that, in theory, and unlike with the Romans, there was

supposed to be a single sexual standard, where adultery was a sin and

against the teachings of the church, regardless of the sex of those

involved. In practice, however, the church seemed to have accepted the

traditional double standard which punished the adultery of the wife more

harshly than that of the husband.

Among Germanic tribes, each tribe had its own laws for adultery, and

many of them allowed the husband to "take the law in his hands" and

commit acts of violence against a wife caught committing adultery. In the Middle Ages, adultery in Vienna was punishable by death through impalement. Austria was one of the last Western countries to decriminalize adultery, in 1997.

The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert, Vol. 1 (1751) noted the legal double standard from that period, it wrote:

"Furthermore, although the husband who violates conjugal trust is

guilty as well as the woman, it is not permitted for her to accuse him,

nor to pursue him because of this crime".

Adultery and the law

Historically, many cultures considered adultery a very serious crime,

some subject to severe punishment, especially for the married woman and

sometimes for her sex partner, with penalties including capital punishment, mutilation, or torture. Such punishments have gradually fallen into disfavor, especially in Western countries from the 19th century. In countries where adultery is still a criminal offense, punishments range from fines to caning

and even capital punishment. Since the 20th century, such laws have

become controversial, with most Western countries repealing them.

However, even in jurisdictions that have decriminalised adultery,

adultery may still have legal consequences, particularly in

jurisdictions with fault-based divorce laws, where adultery almost always constitutes a ground for divorce and may be a factor in property settlement, the custody of children, the denial of alimony, etc. Adultery is not a ground for divorce in jurisdictions which have adopted a no-fault divorce model, but may still be a factor in child custody and property disputes.

International organizations have called for the decriminalising of adultery, especially in the light of several high-profile stoning

cases that have occurred in some countries. The head of the United

Nations expert body charged with identifying ways to eliminate laws that

discriminate against women or are discriminatory to them in terms of

implementation or impact, Kamala Chandrakirana, has stated that: "Adultery must not be classified as a criminal offence at all".

A joint statement by the United Nations Working Group on discrimination

against women in law and in practice states that: "Adultery as a

criminal offence violates women’s human rights".

In Muslim countries that follow Sharia law for criminal justice, the punishment for adultery may be stoning. There are fifteen

countries in which stoning is authorized as lawful punishment, though

in recent times it has been legally carried out only in Iran and

Somalia. Most countries that criminalize adultery are those where the dominant religion is Islam, and several Sub-Saharan African Christian-majority countries, but there are some notable exceptions to this rule, namely Philippines and several U.S. states.

Asia

Adultery is a crime in the Philippines.

In the Philippines, the law differentiates based on the gender of the

spouse. A wife can be charged with adultery, while a husband can only be

charged with the related crime of concubinage, which is more loosely

defined (it requires either keeping the mistress in the family home, or

cohabiting with her, or having sexual relations under scandalous

circumstances). There are currently proposals to decriminalize adultery in the Philippines.

Adultery was a crime in Japan until 1947, in South Korea until 2015, and in Taiwan until 2020.

In 2015, South Korea's Constitutional Court overturned the country's law against adultery.

Previously, adultery was criminalized in 1953, and violators were

subject to two years in prison, with the aim of protecting women from

divorce. The law was overturned because the court found that adultery is

a private matter in which the state should not intervene.

In China, punishments for adultery were differentiated based on gender of the spouse until 1935. Adultery is no longer a crime in the People's Republic of China, but is a ground for divorce.

In Taiwan, adultery was a criminal offense before 2020. The law was challenged in 2002 when it was upheld by the Constitutional Court. Arguments were heard again by the court in March 2020, and the court ruled the law unconstitutional on 29 May 2020. Twelve of fifteen justices issued a concurring opinion, two others concurred in part, and one dissented.

During Qing rule in Taiwan,

the husband or his relatives could bring charges. The standard sentence

was ninety lashes for each of the accused. The woman could be sold or

divorced. The matter could be settled out of court, with bodily harm to

the accused or assorted punishments affecting his social standing. Under

Japanese rule, only the husband could bring charges. The accused could be sentenced to two years imprisonment. Wife selling became illegal, although private settlements still occurred.

In Pakistan, adultery is a crime under the Hudood Ordinance, promulgated in 1979. The Ordinance sets a maximum penalty of death. The Ordinance has been particularly controversial because it requires a woman making an accusation of rape

to provide extremely strong evidence to avoid being charged with

adultery herself. A conviction for rape is only possible with evidence

from no fewer than four witnesses. In recent years high-profile rape

cases in Pakistan have given the Ordinance more exposure than similar

laws in other countries. Similar laws exist in some other Muslim countries, such as Saudi Arabia and Brunei.

On 27 September 2018, the Supreme Court of India ruled that adultery is not a crime. Before 2018, adultery was defined as sex between a man and a woman without the consent of the woman's husband.

The man was prosecutable and could be sentenced for up to five years

(even if he himself was unmarried) whereas the married woman couldn't be

jailed. Men have called the law gender discrimination in that women cannot be prosecuted for adultery

and the National Commission of Women has criticized the British era law

of being anti-feminist as it treats women as the property of their

husbands and has consequently recommended deletion of the law or

reducing it to a civil offense.

Extramarital sex without the consent of one's partner can be a valid

grounds for monetary penalty on government employees, as ruled by the

Central Administrative Tribunal.

In Southwest Asia, adultery has attracted severe sanctions, including the death penalty. In some places, such as Saudi Arabia, the method of punishment for adultery is stoning

to death. Proving adultery under Muslim law can be a very difficult

task as it requires the accuser to produce four eyewitnesses to the act

of sexual intercourse, each of whom should have a good reputation for

truthfulness and honesty. The criminal standards do not apply in the

application of social and family consequences of adultery, where the

standards of proof are not as exacting. Sandra Mackey, author of The Saudis: Inside the Desert Kingdom,

stated in 1987 that in Saudi Arabia, "unlike the tribal rights of a

father to put to death a daughter who has violated her chastity, death

sentences under Koranic law [for adultery] are extremely rare."

In regions of Iraq and Syria under ISIL, there have been reports

of floggings as well as execution of people who engaged in adultery. The

method of execution was typically by stoning.

ISIL would not merely oppose adultery but also oppose behavior that

from their point of view could lead to adultery, such as women not being

covered, people of the opposite sex socializing with one another, or

even female mannequins in store windows.

Europe

Adultery is no longer a crime in any European country.

Adultery in English law

was not a criminal offence in secular law from the later twelfth

century until the seventeenth century. It was punishable under

ecclesiastical law from the twelfth century until jurisdiction over

adultery by ecclesiastical courts in England and Wales was abolished in

England and Wales (and some British territories of the British Empire)

by the Matrimonial Causes Act 1857. However, in English and Welsh common law of tort it was possible from the early seventeenth century for a spouse to prosecute an adulterer for damages on the grounds of loss of consortium until the Law Reform (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1970. Adultery was also illegal under secular statute law for the decade in which the Commonwealth (Adultery) Act (1650) was in force.

Among the last Western European countries to decriminalised adultery were Italy (1969), Malta (1973), Luxembourg (1974), France (1975), Spain (1978), Portugal (1982), Greece (1983), Belgium (1987), Switzerland (1989), and Austria (1997).

In most Communist countries adultery was not a crime. Romania was an exception, where adultery was a crime until 2006,

though the crime of adultery had a narrow definition, excluding

situations where the other spouse encouraged the act or when the act

happened at a time the couple was living separate and apart; and in practice prosecutions were extremely rare.

In Turkey

adultery laws were held to be invalid in 1996/1998 because the law was

deemed discriminatory as it differentiated between women and men. In

2004, there were proposals to introduce a gender-neutral adultery law.

The plans were dropped, and it has been suggested that the objections

from the European Union played a role.

Before the 20th century, adultery was often punished harshly. In

Scandinavia, in the 17th century, adultery and bigamy were subject to

the death penalty, although few people were actually executed. Examples of women who have been executed for adultery in Medieval and Early Modern Europe include Maria of Brabant, Duchess of Bavaria (in 1256), Agnese Visconti (in 1391), Beatrice Lascaris di Tenda (in 1418), Anne Boleyn (in 1536), and Catherine Howard

(in 1542). The enforcement of adultery laws varied by jurisdiction. In

England, the last execution for adultery is believed to have taken place

in 1654, when a woman named Susan Bounty was hanged.

The European Court of Human Rights

(ECHR) has had the opportunity to rule in recent years on several cases

involving the legitimacy of firing a person from their job due to

adultery. These cases dealt with people working for religious

organizations and raised the question of the balancing of the right of a

person to respect for their private life (recognized in the EU) and the

right of religious communities to be protected against undue

interference by the State (recognized also in the EU). These situations

must be analyzed with regard to their specific circumstances, in each

case. The ECtHR had ruled both in favor of the religious organization

(in the case of Obst) and in favor of the fired person (in the case of

Schüth).

Latin America

Until

the 1990s, most Latin American countries had laws against adultery.

Adultery has been decriminalized in most of these countries, including Paraguay (1990), Chile (1994), Argentina (1995), Nicaragua (1996), Dominican Republic (1997), Brazil (2005), and Haiti (2005). In some countries, adultery laws have been struck down by courts on the ground that they discriminated against women, such as Guatemala (1996), where the Guatemalan Constitutional Court struck down the adultery law based both on the Constitution's gender equality clause and on human rights treaties including CEDAW. The adultery law of the Federal Criminal Code of Mexico was repealed in 2011.

Australia

Adultery

is not a crime in Australia. Under federal law enacted in 1994, sexual

conduct between consenting adults (18 years of age or older) is their

private matter throughout Australia,

irrespective of marital status. Australian states and territories had

previously repealed their respective adultery criminal laws. Australia

changed to no-fault divorce in 1975, abolishing adultery as a ground for divorce.

United States

The United States is one of few industrialized countries to have laws criminalizing adultery.

In the United States, laws vary from state to state. Until the mid 20th

century most U.S. states (especially Southern and Northeastern states)

had laws against fornication, adultery or cohabitation. These laws have

gradually been abolished or struck down by courts as unconstitutional.

State criminal laws against adultery are rarely enforced. Federal

appeals courts have ruled inconsistently as to whether these laws are

unconstitutional (especially after the 2003 Supreme Court decision Lawrence v. Texas) and as of 2019 the Supreme Court has not ruled directly on the issue.

As of 2019, adultery is a criminal offense in 19 states, but prosecutions are rare. Pennsylvania abolished its fornication and adultery laws in 1973. States which have decriminalised adultery in recent years include West Virginia (2010), Colorado (2013), New Hampshire (2014), Massachusetts (2018), and Utah (2019).

In the last conviction for adultery in Massachusetts in 1983, it was

held that the statute was constitutional and that "no fundamental

personal privacy right implicit in the concept of ordered liberty

guaranteed by the United States Constitution bars the criminal

prosecution of such persons [adulterers]."

Although adultery laws are mostly found in the conservative states (especially Southern states), there are some notable exceptions such as New York. Idaho, Oklahoma, Michigan, and Wisconsin, where adultery is a felony, while in the other states it is a misdemeanor. It is a Class B misdemeanor in New York and a Class I felony in Wisconsin. Penalties vary from a $10 fine (Maryland) to four years in prison (Michigan).

In South Carolina,

the fine for adultery is up to $500 and/or imprisonment for no more

than one year (South Carolina code 16-15-60), and South Carolina divorce

laws deny alimony to the adulterous spouse. South Carolina's adultery law came into spotlight in 2009, when then governor Mark Sanford

admitted to his extramarital affair. He was not prosecuted for it; it

is not clear whether South Carolina could prosecute a crime that

occurred in another jurisdiction (Argentina in this case); furthermore,

under South Carolina law adultery involves either "the living together

and carnal intercourse with each other" or, if those involved do not

live together "habitual carnal intercourse with each other" which is more difficult to prove.

In Florida

adultery ("Living in open adultery", Art 798.01) is illegal; while

cohabitation of unmarried couples was decriminalized in 2016.

In Alabama adultery is a Class B misdemeanor.

Adultery is a crime in Virginia, so that persons in divorce proceedings may use the Fifth Amendment.

Any criminal convictions for adultery can determine alimony and asset

distribution. In 2016 there was a bill in Virginia to decriminalize

adultery and make it only a civil offense, but the Virginia Senate did not advance the bill.

In the U.S. military, adultery is a potential court-martial offense. The enforceability of adultery laws in the United States is unclear following Supreme Court decisions since 1965 relating to privacy and sexual intimacy of consenting adults. However, occasional prosecutions do occur.

Six U.S. states (Hawaii, North Carolina, Mississippi, New Mexico, South Dakota, and Utah) allow the possibility of the tort action of alienation of affections (brought by a deserted spouse against a third party alleged to be responsible for the failure of the marriage). In a highly publicized case in 2010, a woman in North Carolina won a $9 million suit against her husband's mistress.

Criticism of adultery laws

Political arguments

Laws against adultery have been named as invasive and incompatible with principles of limited government

(see Dennis J. Baker, The Right Not to be Criminalized: Demarcating

Criminal Law's Authority (Ashgate) chapter 2). Much of the criticism

comes from libertarianism,

the consensus among whose adherents is that government must not intrude

into daily personal lives and that such disputes are to be settled

privately rather than prosecuted and penalized by public entities. It is also argued that adultery laws are rooted in religious doctrines; which should not be the case for laws in a secular state.

Opponents of adultery laws regard them as painfully archaic,

believing they represent sanctions reminiscent of nineteenth-century

novels. They further object to the legislation of morality, especially a

morality so steeped in religious doctrine. Support for the preservation

of the adultery laws comes from religious groups and from political

parties who feel quite independent of morality, that the government has

reason to concern itself with the consensual sexual activity of its

citizens … The crucial question is: when, if ever, is the government

justified to interfere in consensual bedroom affairs?

There is a history of adultery laws being abused. In Somerset, England, a somewhat common practice was for husbands to encourage their wives to seduce another man, who they would then sue or blackmail, under laws (for examples see Criminal conversation) prohibiting men from having sex with women married to other men.

Historical context

Historically, in most cultures, laws against adultery were enacted

only to prevent women—and not men—from having sexual relations with

anyone other than their spouses, since women were deemed their husbands' property, with adultery being often defined as sexual intercourse between a married woman and a man other than her husband. Among many cultures the penalty was—and to this day still is, as noted below—capital punishment. At the same time, men were free to maintain sexual relations with any women (polygyny) provided that the women did not already have husbands or "owners". Indeed, בעל (ba`al), Hebrew for husband, used throughout the Bible, is synonymous with owner. These laws were enacted in fear of cuckoldry and thus sexual jealousy. Many indigenous customs, such as female genital mutilation and even menstrual taboos,

have been theorized to have originated as preventive measures against

cuckolding. This arrangement has been deplored by many modern

intellectuals.

Discrimination against women

Opponents

of adultery laws argue that these laws maintain social norms which

justify violence, discrimination and oppression of women; in the form of

state sanctioned forms of violence such as stoning, flogging or hanging for adultery; or in the form of individual acts of violence committed against women by husbands or relatives, such as honor killings, crimes of passion, and beatings. UN Women has called for the decriminalization of adultery. A Joint Statement by the United Nations Working Group on discrimination against women in law and in practice in 2012, stated:

The United Nations Working Group on discrimination

against women in law and in practice is deeply concerned at the

criminalization and penalization of adultery whose enforcement leads to

discrimination and violence against women.

Concerns exist that the existence of "adultery" as a criminal offense

(and even in family law) can affect the criminal justice process in

cases of domestic assaults and killings, in particular by mitigating murder to manslaughter,

or otherwise proving for partial or complete defenses in case of

violence. These concerns have been officially raised by the Council of

Europe and the UN in recent years. The Council

of Europe Recommendation Rec(2002)5 of the Committee of Ministers to

member states on the protection of women against violence states that member states should: (...) "57. preclude adultery as an excuse for violence within the family". UN Women has also stated in regard to the defense of provocation

and other similar defenses that "laws should clearly state that these

defenses do not include or apply to crimes of 'honour', adultery, or

domestic assault or murder."

Use of limited resources of the criminal law enforcement

An

argument against the criminal status of adultery is that the resources

of the law enforcement are limited, and that they should be used

carefully; by investing them in the investigation and prosecution of

adultery (which is very difficult) the curbing of serious violent crimes

may suffer.

The importance of consent as the basis of sexual offenses legislation

Human rights organizations have stated that legislation on sexual crimes must be based on consent,

and must recognize consent as central, and not trivialize its

importance; doing otherwise can lead to legal, social or ethical abuses.

Amnesty International, when condemning stoning legislation that targets

adultery, among other acts, has referred to "acts which should never be

criminalized in the first place, including consensual sexual relations

between adults".

Salil Shetty, Amnesty International's Secretary General, said: "It is

unbelievable that in the twenty-first century some countries are

condoning child marriage and marital rape while others are outlawing abortion, sex outside marriage and same-sex sexual activity – even punishable by death." The My Body My Rights

campaign has condemned state control over individual sexual and

reproductive decisions; stating "All over the world, people are coerced,

criminalized and discriminated against, simply for making choices about

their bodies and their lives".

Consequences

General

For various reasons, most couples who marry do so with the expectation of fidelity. Adultery is often seen as a breach of trust and of the commitment that had been made during the act of marriage. Adultery can be emotionally traumatic for both spouses and often results in divorce.

Adultery may lead to ostracization from certain religious or social groups.

Adultery can also lead to feelings of guilt and jealousy in the

person with whom the affair is being committed. In some cases, this

"third person" may encourage divorce (either openly or subtly).

If the cheating spouse has hinted at divorce in order to continue the

affair, the third person may feel deceived if that does not happen.

They may simply withdraw with ongoing feelings of guilt, carry on an

obsession with their lover, may choose to reveal the affair, or in rare

cases commit violence or other crimes.

While there is correlation, there is no evidence that divorces causes children to have struggles in later life.

If adultery leads to divorce, it also carries higher financial burdens. For example, living expenses and taxes are generally cheaper for married couples than for divorced couples. Legal fees can add up into the tens of thousands of dollars. Divorced spouses may not qualify for benefits such as health insurance, which must then be paid out-of-pocket.

Depending on jurisdiction, adultery may negatively affect the outcome

of the divorce for the "guilty" spouse, even if adultery is not a

criminal offense.

Sexually transmitted infections

Like any sexual contact, extramarital sex opens the possibility of

the introduction of sexually-transmitted diseases (STDs) into a

marriage. Since most married couples do not routinely use barrier contraceptives, STDs can be introduced to a marriage partner by a spouse engaging in unprotected extramarital sex. This can be a public health

issue in regions of the world where STDs are common, but addressing

this issue is very difficult due to legal and social barriers – to

openly talk about this situation would mean to acknowledge that adultery

(often) takes place, something that is taboo in certain cultures,

especially those strongly influenced by religion. In addition, dealing

with the issue of barrier contraception in marriage in cultures where

women have very few rights is difficult: the power of women to negotiate

safer sex (or sex in general) with their husbands is often limited. The World Health Organization (WHO) found that women in violent relations were at increased risk of HIV/AIDS,

because they found it very difficult to negotiate safe sex with their

partners, or to seek medical advice if they thought they have been

infected.

Violence

Historically, female adultery often resulted in extreme violence, including murder (of the woman, her lover, or both, committed by her husband). Today, domestic violence is outlawed in most countries.

Honor killing

Honor killings are often connected to accusations of adultery. Honor killings continue to be practiced in some parts of the world,

particularly (but not only) in parts of South Asia and the Middle East.

Honor killings are treated leniently in some legal systems.

Honor killings have also taken place in immigrant communities in

Europe, Canada and the U.S. In some parts of the world, honor killings

enjoy considerable public support: in one survey, 33.4% of teenagers in

Jordan's capital city, Amman, approved of honor killings. A survey in Diyarbakir,

Turkey, found that, when asked the appropriate punishment for a woman

who has committed adultery, 37% of respondents said she should be

killed, while 21% said her nose or ears should be cut off.

Until 2009, in Syria, it was legal for a husband to kill or injure his wife or his female relatives caught in flagrante delicto

committing adultery or other illegitimate sexual acts. The law has

changed to allow the perpetrator to only "benefit from the attenuating

circumstances, provided that he serves a prison term of no less than two

years in the case of killing."

Other articles also provide for reduced sentences. Article 192 states

that a judge may opt for reduced punishments (such as short-term

imprisonment) if the killing was done with an honorable intent. Article

242 says that a judge may reduce a sentence for murders that were done

in rage and caused by an illegal act committed by the victim.

In recent years, Jordan has amended its Criminal Code to modify its

laws which used to offer a complete defense for honor killings.

According to the UN in 2002:

- "The report of the Special Rapporteur

... concerning cultural practices in the family that are violent

towards women (E/CN.4/2002/83), indicated that honour killings had been

reported in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon, Morocco, Pakistan, the Syrian Arab Republic, Turkey, Yemen,

and other Mediterranean and Persian Gulf countries, and that they had

also taken place in western countries such as France, Germany and the

United Kingdom, within migrant communities."

Crimes of passion

Crimes of passion are often triggered by jealousy, and, according to Human Rights Watch,

"have a similar dynamic [to honor killings] in that the women are

killed by male family members and the crimes are perceived as excusable

or understandable."

Stoning

Stoning, or lapidation, refers to a form of capital punishment

whereby an organized group throws stones at an individual until the

person dies, or the condemned person is pushed from a platform set high

enough above a stone floor that the fall would probably result in

instantaneous death.

Stoning continues to be practiced today, in parts of the world.

Recently, several people have been sentenced to death by stoning after

being accused of adultery in Iran, Somalia, Afghanistan, Sudan, Mali,

and Pakistan by tribal courts.

Flogging

In some jurisdictions flogging is a punishment for adultery.

There are also incidents of extrajudicial floggings, ordered by

informal religious courts. In 2011, a 14-year-old girl in Bangladesh

died after being publicly lashed, when she was accused of having an

affair with a married man. Her punishment was ordered by villagers under

Sharia law.

Violence between the partners of an adulterous couple

Married

people who form relations with extramarital partners or people who

engage in relations with partners married to somebody else may be

subjected to violence in these relations.

Because of the nature of adultery – illicit or illegal in many

societies – this type of intimate partner violence may go underreported

or may not be prosecuted when it is reported; and in some jurisdictions

this type of violence is not covered by the specific domestic violence laws meant to protect persons in 'legitimate' couples.

In fiction

The theme of adultery has been used in many literary works, and has served as a theme for notable books such as Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, Lady Chatterley's Lover, The Scarlet Letter and Adultery. It has also been the theme of many movies.