National Government Den nasjonale regjering | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942–1945 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Puppet state in German-occupied Norway | ||||||||

| Capital | Oslo | ||||||||

| Common languages | Norwegian | ||||||||

| Religion | Lutheranism | ||||||||

| Government | Nazi one-party totalitarian duumvirate | ||||||||

| Reichskommissar | |||||||||

• 1940–1945 | Josef Terboven | ||||||||

• 1945 | Franz Böhme (acting) | ||||||||

| Minister President | |||||||||

• 1942–1945 | Vidkun Quisling | ||||||||

| Historical era | World War II | ||||||||

• Proclamation | 1 February 1942 | ||||||||

• German capitulation | 9 May 1945 | ||||||||

| Currency | Norwegian krone (NOK) | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||

The Quisling regime or Quisling government are common names used to refer to the fascist collaborationist government led by Vidkun Quisling in German-occupied Norway during the Second World War. The official name of the regime from 1 February 1942 until its dissolution in May 1945 was Den nasjonale regjering (English: the National Government). Actual executive power was retained by the Reichskommissariat Norwegen, headed by Josef Terboven.

Given the use of the term quisling, the name Quisling regime can also be used as a derogatory term referring to political regimes perceived as treasonous puppet governments imposed by occupying foreign enemies.

1940 coup

Vidkun Quisling, Fører of the Nasjonal Samling party, had first tried to carry out a coup against the Norwegian government on 9 April 1940, the day of the German invasion of Norway. At 7:32 p.m., Quisling visited the studios of the Norwegian Broadcasting Corporation and made a radio broadcast proclaiming himself Prime Minister and ordering all resistance to halt at once. He announced that he and Nasjonal Samling were taking power due to Nygaardsvold's Cabinet having "raised armed resistance and promptly fled". He further declared that in the present situation it was "the duty and the right of the movement of Nasjonal Samling to take over governmental power". Quisling claimed that the Nygaardsvold Cabinet had given up power despite that it had only moved to Elverum, which is some 50 km (31 mi) from Oslo, and was carrying out negotiations with the Germans.

The next day, German ambassador Curt Bräuer traveled to Elverum and demanded King Haakon VII return to Oslo and formally appoint Quisling as prime minister. Haakon stalled for time, telling the ambassador that Norwegian kings could not make political decisions on their own authority. At a Cabinet meeting later that night, Haakon said that he could not in good conscience appoint Quisling as prime minister because he knew neither the people nor the Storting had confidence in him. Haakon further stated that he would abdicate rather than appoint a government headed by Quisling. By this time, news of Quisling's attempted coup had reached Elverum. Negotiations promptly collapsed, and the government unanimously advised Haakon not to appoint Quisling as prime minister.

Quisling tried to have the Nygaardsvold Cabinet arrested, but the officer he instructed to carry out the arrest ignored the warrant. Attempts at gaining control over the police force in Oslo by issuing orders to the chief of police Kristian Welhaven also failed. The coup failed after six days, despite German support for the first three days, and Quisling had to step aside in the occupied parts of Norway in favour of the Administrative Council (Administrasjonsrådet). The Administrative Council was formed on 15 April by members of the Supreme Court and supported by Norwegian business leaders as well as Bräuer as an alternative to Quisling's Nasjonal Samling in the occupied areas.

Provisional Councillors of State

On 25 September 1940, German Reichskommissar Josef Terboven, who on 24 April 1940 had replaced Curt Bräuer as the top civilian commander in Norway, proclaimed the deposition of King Haakon VII and the Nygaardsvold Cabinet, banning all political parties other than Nasjonal Samling. Terboven then appointed a group of 11 kommissariske statsråder (English: provisional councillors of state) from Nasjonal Samling to help him in governing Norway. Although the provisional councillors of state did not form a government, the intention of the Germans was to use them to prepare the way for a Nasjonal Samling take-over of power in the future. Vidkun Quisling was made the political head of the councillors and all members of Nasjonal Samling had to swear a personal oath of allegiance to him. Most of the councillors worked diligently at introducing Nasjonal Samling ideals and politics. Amongst the schemes introduced during the council period was the introduction of labour duty, reforms of the labour market, the penal code and the system of justice, a reorganization of the police and the introduction of national socialist ideals in the Norwegian culture scene. The provisional councillors of state were intended as a temporary system while Nasjonal Samling built up its organization in preparation for assuming full governmental powers. On 25 September 1941, the one-year anniversary of the councillors, Terboven gave them the title of "ministers".

Government

With the establishment of Quisling's national government, Quisling, as minister-president, temporarily assumed the authority of both the King and the Parliament.

In 1942, after two years of direct civilian administration by the Germans (which continued de facto until 1945), he was finally put in charge of a collaborationist government, which was officially proclaimed on 1 February 1942. The official name of the government was "Den nasjonale regjering" (English: the National Government). The original intention of the Germans had been to hand over the sovereignty of Norway to the new government, but by mid-January 1942 Hitler decided to retain the civilian Reichskommissariat Norwegen under Terboven. The Quisling government was instead given the role of an occupying authority with wide-ranging authorisations. Quisling himself viewed the creation of his government as a "decisive step on the road towards the complete independence of Norway". Although having only temporarily assumed the King's authority, Quisling still made efforts to distance his regime from the exiled monarchy. After Quisling moved into the Royal Palace he took back into use the official seal of Norway, changing the wording from "Haakon VII Norges konge" to "Norges rikes segl" (in English translation, from "Haakon VII King of Norway" to "The Seal of the Norwegian Realm"). After establishing national government Quisling claimed to hold "the authority that according to the Constitution belonged to the King and Parliament".

Other important ministers of the collaborationist government were Jonas Lie (also head of the Norwegian wing of the SS from 1941) as Minister of the Police, Dr. Gulbrand Lunde as Minister of Culture and Enlightenment, as well as the opera singer Albert Viljam Hagelin, who was Minister of the Interior.

Politics

One of Quisling's first actions was to reintroduce the prohibition of Jews entering Norway, which was formerly a part of the Constitution's §2 from 1814 to 1851.

Two of the early laws of the Quisling regime, Lov om nasjonal ungdomstjeneste (English: 'Law on national youth service') and Lov om Norges Lærersamband (English: 'The Norges Teacher Liaison'), both signed 5 February 1942, led to massive protests from parents, serious clashes with the teachers, and an escalating conflict with the Church of Norway. Schools were closed for one month, and in March 1942 around 1,100 teachers were arrested by the Norwegian police and sent to German prisons and concentration camps, and about 500 of the teachers were forced to Kirkenes as construction workers for the German occupants.

Goal of independence

Even after the official creation of the Quisling government, Josef Terboven still ruled Norway as a dictator, taking orders from no-one but Hitler. Quisling's regime was a puppet government, although Quisling wanted independence and the recall of Terboven, something he constantly lobbied Hitler for, without success. Quisling wanted to achieve independence for Norway under his rule, with an end to the German occupation of Norway through a peace treaty and the recognition of Norway's sovereignty by Germany. He further wanted to ally Norway to Germany and join the Anti-Comintern Pact. After a reintroduction of national service in Norway, Norwegian troops were to fight with the Axis powers in the Second World War.

Quisling also fronted the idea of a pan-European union led, but not dominated, by Germany, with a common currency and a common market. Quisling presented his plans to Hitler repeatedly in memos and talks with the German dictator, the first time 13 February 1942 in the Reich Chancellery in Berlin and the last time on 28 January 1945, again in the Reich Chancellery. All of Quisling's ideas were rejected by Hitler, who did not want any permanent agreements before the war had been concluded, while also desiring Norway's outright annexation into Germany as the northernmost province of a Greater Germanic Reich. Hitler did, however, in an April 1943 meeting promise Quisling that once the war was over Norway would regain her independence. This is the only known case of Hitler making such a promise to an occupied country.

The word Quisling has become synonymous with treachery and collaboration with the enemy.

Territorial claims

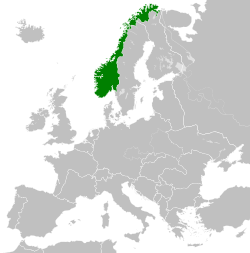

The regime looked nostalgically to the High Middle Ages of the country's history, known in Norwegian historiography as Norgesveldet, during which Norwegian territory extended beyond its current borders. Quisling envisioned an extension of the Norwegian state by its annexation of the Kola peninsula with its small Norwegian minority, so a Greater Norway spanning the entire North European coastline could be created. Further expansion was expected in Northern Finland, to link the Kola peninsula with Finnmark: Nasjonal Samling leaders had mixed views on the post-war Finnish-Norwegian border, but the potential Norwegian annexation of at least the Finnish municipalities of Petsamo (Norwegian: Petsjenga) and Inari (Norwegian: Enare) was under consideration.

Nasjonal Samling publications called for the annexation of the historically Norwegian Swedish provinces of Jämtland (Norwegian: Jemtland), Härjedalen (Norwegian: Herjedalen, see also Øst-Trøndelag) and Bohuslän (Norwegian: Båhuslen) In March 1944, Quisling met with Wehrmacht general Rudolf Bamler, and urged the Germans to invade Sweden from Finnish Lapland (using the forces delegated to the German Lapland Army) and through the Baltic as a preemptive strike against Sweden joining the war on the Allied side. Quisling's proposal was sent to both OKW chief Alfred Jodl and SS leader Heinrich Himmler.

Quisling and Jonas Lie, leader of the Germanic SS in Norway, also furthered irredentist Norwegian claims to the Faroes (Norwegian: Færøyene), Iceland (Norwegian: Island), Orkney (Norwegian: Orknøyene), Shetland (Norwegian: Hjaltland), the Outer Hebrides (historically a part of the Norse Kingdom of Mann and the Isles under the name Sørøyene, "South Islands") and Franz Josef Land (earlier claimed by Norway under the name Fridtjof Nansen Land), most of which were former Norwegian territories passed on to Danish rule after the dissolution of Denmark-Norway in 1814, while the rest were former Viking Age settlements. Norway had already claimed a part of Eastern Greenland in 1931 (under the name Eirik Raudes Land), but the claim was extended during the occupation period to cover Greenland as a whole. During the spring of 1941, Quisling laid out plans to "reconquer" the island using a task force of a hundred men, but the Germans deemed this plan unfeasible. In the person of propaganda minister Gulbrand Lunde the Norwegian puppet government further lay claim to the North and South Poles. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Norway had gained prestige as a nation active in polar expedition: the South Pole was first reached by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen in 1911, and in 1939 Norway had claimed a region of Antarctica under the name Queen Maud Land (Norwegian: Dronning Maud Land).

After Germany's invasion of the Soviet Union preparations were made for establishing Norwegian colonies in Northern Russia. Quisling designated the area reserved for Norwegian colonization as Bjarmeland, a reference to the name featured in the Norse sagas for Northern Russia.

Dissolution

Quisling's regime ceased to exist in 1945, with the end of World War II in Europe. Norway was still under occupation in May 1945, but Vidkun Quisling and most of his ministers surrendered at Møllergata 19 police station on 9 May, one day after Germany's surrender. The new Norwegian unification government tried him on 20 August for numerous crimes; he was convicted on 10 September and was executed by firing squad on 24 October 1945. Other Nazi collaborators, as well as Germans accused of war crimes, were also arrested and tried during this legal purge.

Ministers of the Quisling regime

The ministers of the Quisling regime in 1942 were:

- Eivind Blehr (Minister of Trade and Minister of Supplies)

- Thorstein Fretheim (Minister of Agriculture)

- Rolf Jørgen Fuglesang (Minister of Party Affairs)

- Albert Viljam Hagelin (Minister of Domestic Affairs)

- Tormod Hustad (Minister of Labour)

- Kjeld Stub Irgens (Minister of Shipping)

- Jonas Lie (Minister of Police)

- Johan Andreas Lippestad (Minister of Social Affairs)

- Gulbrand Lunde (Minister of Culture)

- Frederik Prytz (Minister of Finance)

- Sverre Riisnæs (Minister of Justice)

- Ragnar Skancke (Minister for Church and Educational Affairs)

- Axel Heiberg Stang (Minister of the Labour Service and Sports)

The Quisling regime's leadership saw significant reshuffling and replacements during its existence. When Gulbrand Lunde died in 1942, Rolf Jørgen Fuglesang took over his ministry as well as retaining his own. Eivind Blehr's two ministries were merged in 1943 as the Ministry of Commerce. On 4 November 1943 Alf Whist joined the government as a minister without portfolio.

Tormod Hustad was replaced by Hans Skarphagen on 1 February 1944. Both Kjeld Stub Irgens and Eivind Blehr were fired in June 1944. Their former ministries were merged and placed under the control of Alf Whist as Minister of Commerce. On 8 November 1944, Albert Viljam Hagelin was fired from his position and replaced by Arnvid Vasbotten. When Frederik Prytz died in February 1945, he was replaced by Per von Hirsch. Thorstein Fretheim was fired on 21 April 1945, to be replaced by Trygve Dehli Laurantzon.