How brand new science will manage the fourth industrial revolution – “Managing the Machines”

It’s

about artificial intelligence, data, and things like quantum computing

and nanotechnology. Australian National University’s 3A Institute is

creating a new discipline to manage this revolution and its impact on

humanity.

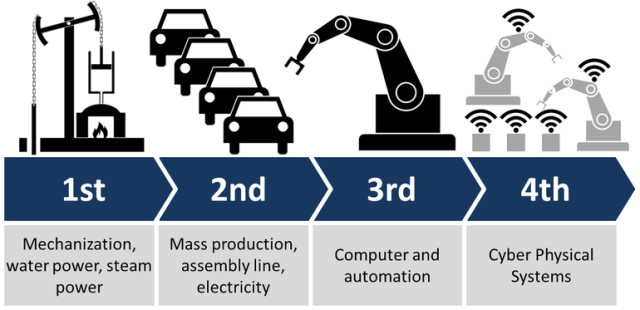

Image: Diagram by Christoph Roser at AllAboutLean.com (CC BY-SA 4.0))

Diagrams explaining the fourth industrial revolution,

like this one by Christoph Roser, are OK as far as they go. Apart from

the term “cyber physical systems”. Ugh. What they mean is that physical

systems are becoming digital. Think of the Internet of Things (IoT)

supercharged by artificial intelligence (AI).

But

according to Distinguished Professor Genevieve Bell, these diagrams are

missing something rather important: Humans and their social structures.

“Now

for those of us who’ve come out of the social sciences and humanities,

this is an excellent chart because of the work it does in tidying up

history,” Bell said in her lecture at the Trinity Long Room Hub at

Trinity College Dublin in July.

“It

doesn’t help if what you want to think about was what else was going

on. Each one of those technological transformations was also about

profound shifts in cultural practice, social structure, social

organisations, profoundly different ideas about citizenship, governance,

regulation, ideas of civil and civic society.”

Another problem with this simplistic view is the way the Industry 4.0 folks

attach dates to this chart. Steam power and mechanisation in 1760-1820

or so. Mass production from maybe 1870, but the most famous chapter

being Henry Ford’s work in 1913. Then computers and automation started

being used to manage manufacturing from 1950.

“That

time scheme works really well if you’re in the West. It doesn’t hold if

you’re in China or India or Latin America or Africa, where most of

those things happened in the 20th century, many of them since 1945,”

Bell said.

Bell wants to know what we can learn from those first three revolutions. She heads the 3A Institute at the Australian National University, which was launched in September 2017 and is working out how we should respond to, and perhaps even direct, the fourth revolution.

Take

the steam engines of the first industrial revolution. They were built

by blacksmiths and ironmongers, who knew what they needed to build the

engines. But they didn’t know how to shape the industries the engines

could power, or how to house them, or about the safety systems they’d

need. These and other problems generated the new applied science of

engineering. The first school of engineering, the École Polytechnique,

was established in Paris in 1794.

The

large-scale factories and railway systems of the second industrial

revolution needed massive amounts of money. Raising and managing that

money literally led to capitalism, and concepts like common stock

companies and futures trading. And the first business school with

funding from industry.

Early

in the computer revolution, the US government had a problem. Nearly all

of its computers relied on proprietary software from companies like IBM

and Honeywell. So it asked Stanford University mathematician George

Forsythe to create an abstract language for all computers. Two years

later, his team developed a thing called computer science, and issued a

standard 10-page curriculum. An updated version is still used globally

today.

“So,

engineering, business, and computer science: Three completely different

applied sciences, emerging from three completely different technical

regimes, with different impulses,” Bell said.

“Each

starts out incredibly broad in terms of the ideas it draws on, rapidly

narrows to a very clear set of theoretical tools and an idea about

practice, then is scaled very quickly.”

With

this in mind, Bell said that the fourth industrial revolution needs its

own applied science, so that’s exactly what the 3A Institute is going

to build — as the website puts it, “a new applied science around the

management of artificial intelligence, data, and technology and of their

impact on humanity”.

And the 3A Institute plans to do it by 2022.

Nine months into this grand project, it’s identified five sets of questions that this new science needs to answer.

First is Autonomy

If

autonomous systems are operating without prewritten rules, how do we

stop them turning evil, as so many fictional robots do? How do different

autonomous systems interact? How do we regulate those interactions? How

do you secure those systems and make them safe? How do the rules change

when the systems cross national boundaries?

Or,

as Bell asked, “What will it mean to live in a world where objects act

without reference to us? And how do we know what they’re doing? And do

we need to care?”

Second is Agency,

which is really about the limits to an object’s autonomy. With an

autonomous vehicle, for example, does it have to stop at the border? If

so, which border? Determined by whom? Under what circumstances?

“Does your car then have to be updated because of Brexit, and if so how would you do that?” Bell asked.

If

autonomous vehicles are following rules, how are those rules litigated?

Do the rules sit on the object, or somewhere else? If there’s some

network rule that gets vehicles off the road to let emergency vehicles

through, who decides that and how? If you have multiple objects with

different rule sets, how do they engage each other?

Third is Assurance,

and as Bell explained, “sitting under it [is] a whole series of other

words. Safety, security, risk, trust, liability, explicability,

manageability.”

Fourth is Metrics

“The

industrial revolution thus far has proceeded on the notion that the

appropriate metric was an increase in productivity or efficiency. So

machines did what humans couldn’t, faster, without lunch breaks,

relentlessly,” Bell said.

Doing

it over again, we might have done things differently, she said. We

might have included environmental sustainability as a metric.

“What

you measure is what you make, and so imagining that we put our metrics

up at the front would be a really interesting way of thinking about

this.”

Metrics for fourth revolution systems might include safety, quality of decision-making, and quality of data collection.

Some

AI techniques, including deep learning, are energy intensive. Around 10

percent of the world’s energy already goes into running server farms.

Maybe an energy efficiency metric would mean that some tasks would be

done more efficiently by a human.

Fifth and finally are Interfaces. Our current systems for human-computer interaction (HCI) might not work well with autonomous systems.

“These

are objects that you will live in, be moved around by, that may live in

you, that may live around you and not care about you at all … the way

we choose to engage with those objects feels profoundly different to the

way HCI has gotten us up until this moment in time,” Bell said.

“What

would it mean to [have] systems that were, I don’t know, nurturing?

Caring? The robots that didn’t want to kill us, but wanted to look after

us.”

As

with computer science before it, the 3A Institute is developing a

curriculum for this as-yet-unnamed new science. The first draft will be

tested on 10 graduate students in 2019.

Bell’s

speech in Dublin, titled “Managing the Machines”, included much more

detail than reported here. Versions are being presented around the

planet, and videos are starting to appear. This writer highly recommends

them.