Hugh Everett III | |

|---|---|

Hugh Everett in 1964 | |

| Born | November 11, 1930 |

| Died | July 19, 1982 (aged 51) |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Alma mater | Catholic University of America Princeton University (Ph.D.) |

| Known for | Many-worlds interpretation Everett's theorem |

| Children | Elizabeth Everett, Mark Oliver Everett |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics Operations research Optimization Game theory |

| Institutions | Institute for Defense Analyses American Management Systems Monowave Corporation |

| Doctoral advisor | John Archibald Wheeler |

Hugh Everett III (/ˈɛvərɪt/; November 11, 1930 – July 19, 1982) was an American physicist who first proposed the many-worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum physics, which he termed his "relative state" formulation. In contrast to the then-dominant Copenhagen interpretation, the MWI posits that the wave function never collapses and that all possibilities of a quantum superposition are objectively real.

Discouraged by the scorn of other physicists for MWI, Everett ended his physics career after completing his PhD. Afterwards, he developed the use of generalized Lagrange multipliers for operations research and applied this commercially as a defense analyst and a consultant. In poor health later in life, he died at the age of 51 in 1982. He is the father of musician Mark Oliver Everett.

Although largely disregarded until near the end of Everett's lifetime, the MWI received more credibility with the discovery of quantum decoherence in the 1970s and has received increased attention in recent decades, becoming one of the mainstream interpretations of quantum mechanics alongside Copenhagen, pilot wave theories, and consistent histories.

Early life and education

Hugh Everett III was born in 1930 and raised in the Washington, D.C. area. Everett's parents separated when he was young. Initially raised by his mother (Katherine Lucille Everett née Kennedy), he was raised by his father (Hugh Everett Jr) and stepmother (Sarah Everett née Thrift) from the age of seven.

At the age of twelve he wrote a letter to Albert Einstein asking him whether that which maintained the universe was something random or unifying. Einstein responded as follows:

Dear Hugh: There is no such thing like an irresistible force and immovable body. But there seems to be a very stubborn boy who has forced his way victoriously through strange difficulties created by himself for this purpose. Sincerely yours, A. Einstein

Everett won a half scholarship to St. John's College High School in Washington, D.C. From there, he moved to the nearby Catholic University of America to study chemical engineering as an undergraduate. While there, he read about Dianetics in Astounding Science Fiction. Although he never exhibited any interest in Scientology (as Dianetics became), he did retain a distrust of conventional medicine throughout his life.

During World War II his father was away fighting in Europe as a lieutenant colonel on the general staff. After World War II, Everett's father was stationed in West Germany, and Hugh joined him, during 1949, taking a year out from his undergraduate studies. Father and son were both keen photographers and took hundreds of pictures of West Germany being rebuilt. Reflecting their technical interests, the pictures were "almost devoid of people".

Princeton

Everett graduated from the Catholic University of America in 1953 with a degree in chemical engineering, although he had completed sufficient courses for a mathematics degree as well. He received a National Science Foundation fellowship that allowed him to attend Princeton University for graduate studies. He started his studies at Princeton in the mathematics department, where he worked on the then-new field of game theory under Albert W. Tucker, but slowly drifted into physics. In 1953 he started taking his first physics courses, notably Introductory Quantum Mechanics with Robert Dicke.

During 1954, he attended Methods of Mathematical Physics with Eugene Wigner, although he remained active with mathematics and presented a paper on military game theory in December. He passed his general examinations in the spring of 1955, thereby gaining his master's degree, and then started work on his dissertation that would (much) later make him famous. He switched thesis advisor to John Archibald Wheeler some time in 1955, wrote a couple of short papers on quantum theory and completed his long paper, Wave Mechanics Without Probability in April 1956.

In his third year at Princeton, Everett moved into an apartment which he shared with three friends he had made during his first year, Hale Trotter, Harvey Arnold and Charles Misner. Arnold later described Everett as follows:

He was smart in a very broad way. I mean, to go from chemical engineering to mathematics to physics and spending most of the time buried in a science fiction book, I mean, this is talent.

It was during this time that he met Nancy Gore, who typed up his Wave Mechanics Without Probability paper. Everett married Nancy Gore the next year. The long paper was later retitled as The Theory of the Universal Wave Function.

Wheeler himself had traveled to Copenhagen in May 1956 with the goal of getting a favorable reception for at least part of Everett's work, but in vain. In June 1956 Everett started defense work in the Pentagon's Weapons Systems Evaluation Group, returning briefly to Princeton to defend his thesis after some delay in the spring of 1957. A short article, which was a compromise between Everett and Wheeler about how to present the concept and almost identical to the final version of his thesis, was published in Reviews of Modern Physics Vol 29 #3 454-462, (July 1957), accompanied by an approving review by Wheeler. Everett was not happy with the final form of the article. Everett received his Ph.D. in physics from Princeton in 1957 after completing his doctoral dissertation titled "On the foundations of quantum mechanics."

After Princeton

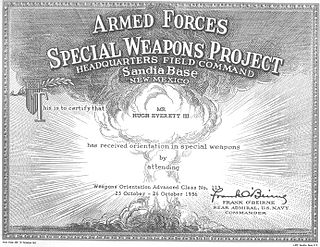

Upon graduation in September 1956, Everett was invited to join the Pentagon's newly-forming Weapons Systems Evaluation Group (WSEG), managed by the Institute for Defense Analyses. Between 23–26 October 1956 he attended a weapons orientation course managed by Sandia National Laboratories at Albuquerque, New Mexico to learn about nuclear weapons and became a fan of computer modeling while there. In 1957, he became director of the WSEG's Department of Physical and Mathematical Sciences. After a brief intermission to defend his thesis on quantum theory at Princeton, Everett returned to WSEG and recommenced his research, much of which, but by no means all, remains classified. He worked on various studies of the Minuteman missile project, which was then starting, as well as the influential study The Distribution and Effects of Fallout in Large Nuclear Weapon Campaigns.

During March and April 1959, at Wheeler's request, Everett visited Copenhagen, on vacation with his wife and baby daughter, in order to meet with Niels Bohr, the "father of the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics". The visit was a complete disaster; Everett was unable to communicate the main idea that the universe is describable, in theory, by an objectively existing universal wave function (which does not "collapse"); this was simply heresy to Bohr and the others at Copenhagen. The conceptual gulf between their positions was too wide to allow any meeting of minds; Léon Rosenfeld, one of Bohr's devotees, talking about Everett's visit, described Everett as being "undescribably [sic] stupid and could not understand the simplest things in quantum mechanics". Everett later described this experience as "hell...doomed from the beginning".

However, while in Copenhagen, in his hotel, he started work on a new idea to use generalized Lagrange multipliers for mathematical optimization. Everett's theorem, published in 1963, relates the Lagrangian bidual to the primal problem.

In 1962 Everett accepted an invitation to present the relative-state formulation (as it was still called) at a conference on the foundations of quantum mechanics held at Xavier University in Cincinnati. In his exposition Everett presented his derivation of probability and also stated explicitly that observers in all branches of the wavefunction were equally "real." He also agreed with an observation from the floor that the number of branches of the universal wavefunction was an uncountable infinity.

In August 1964, Everett and several WSEG colleagues started Lambda Corp. to apply military modeling solutions to various civilian problems. During the early 1970s, defense budgets were curtailed and most money went to operational duties in the Vietnam War, resulting in Lambda eventually being absorbed by the General Research Corp.

In 1973, Everett and Donald Reisler (a Lambda colleague and fellow physicist) left the firm to establish DBS Corporation in Arlington, Virginia. Although the firm conducted defense research (including work on United States Navy ship maintenance optimization and weapons applications), it primarily specialized in "analyzing the socioeconomic effects of government affirmative action programs" as a contractor under the auspices of the Department of Justice and the Department of Health, Education and Welfare. For a period of time, the company was partially supported by American Management Systems, a business consulting firm that drew upon algorithms developed by Everett. He concurrently held a non-administrative vice presidency at AMS and was frequently consulted by the firm's founders.

Everett cultivated an early aptitude for computer programming at IDA and favored the TRS-80 at DBS, where he primarily worked for the rest of his life.

Later recognition

In 1970 Bryce DeWitt wrote an article for Physics Today on Everett's relative-state theory, which evoked a number of letters from physicists. These letters, and DeWitt's responses to the technical objections raised, were also published. Meanwhile DeWitt, who had corresponded with Everett on the many-worlds / relative state interpretation when originally published in 1957, started editing an anthology on the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. In addition to the original articles by Everett and Wheeler, the anthology was dominated by the inclusion of Everett's 1956 paper The Theory of the Universal Wavefunction, which had never been published before. The book was published late in 1973, sold out completely, and it was not long before an article on Everett's work appeared in the science fiction magazine, Analog.

In 1977, Everett was invited to give a talk at a conference Wheeler had organised at Wheeler's new location at the University of Texas at Austin. As with the Copenhagen visit, Everett vacationed from his defense work and traveled with his family. Everett met DeWitt there for the first and only time. Everett's talk was quite well received and influenced a number of physicists in the audience, including Wheeler’s graduate student, David Deutsch, who later promoted the many-worlds interpretation to a wider audience. Everett, who "never wavered in his belief in his many-worlds theory", enjoyed the presentation; it was the first time for years he had talked about his quantum work in public. Wheeler started the process of returning Everett to a physics career by establishing a new research institute in California, but nothing came of this proposal. Wheeler, although happy to introduce Everett's ideas to a wider audience, was not happy to have his own name associated with Everett's ideas. Eventually, after Everett's death, he formally renounced the theory.

Death and legacy

At the age of 51, Everett, who believed in quantum immortality, died suddenly of a heart attack at home in his bed on the night of July 18–19, 1982. Everett's obesity, frequent chain-smoking and alcohol drinking almost certainly contributed to this, although he seemed healthy at the time. A committed atheist, he had asked that his remains be disposed of in the trash after his death. His wife kept his ashes in an urn for a few years, before complying with his wishes. About Hugh's death his son, Mark Oliver Everett, later said:

I think about how angry I was that my dad didn't take better care of himself. How he never went to a doctor, let himself become grossly overweight, smoked three packs a day, drank like a fish and never exercised. But then I think about how his colleague mentioned that, days before dying, my dad had said he lived a good life and that he was satisfied. I realize that there is a certain value in my father's way of life. He ate, smoked and drank as he pleased, and one day he just suddenly and quickly died. Given some of the other choices I'd witnessed, it turns out that enjoying yourself and then dying quickly is not such a hard way to go.

Of the companies Everett initiated, only Monowave Corporation still exists (in Seattle as of March 2015). It is managed by co-founder Elaine Tsiang, who received a Ph.D. in physics under Bryce DeWitt at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill before working for DBS as a programmer.

Everett's daughter, Elizabeth, died by suicide in 1996 (saying in her suicide note that she wished her ashes to be thrown out with the garbage so that she might "end up in the correct parallel universe to meet up w[ith] Daddy"), and in 1998, his wife, Nancy, died of cancer. Everett's son, Mark Oliver Everett, who found Everett dead, is also known as "E" and is the main singer and songwriter for the band Eels. The Eels album Electro-Shock Blues, which was written during this time period, is representative of these deaths.

Mark Everett explored his father's work in the hour-long BBC television documentary Parallel Worlds, Parallel Lives. The program was edited and shown on the Public Broadcasting Service's Nova series in the USA during October 2008. In the program, Mark mentions how he wasn't aware of his father's status as a brilliant and influential physicist until his death in 1982.