From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Niels Bohr | |

|---|---|

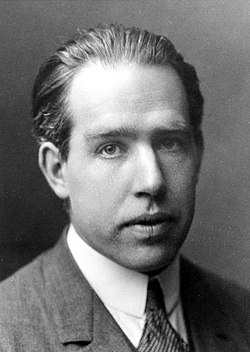

Bohr in 1922

|

|

| Born | Niels Henrik David Bohr 7 October 1885 Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Died | 18 November 1962 (aged 77) Copenhagen, Denmark |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | |

| Alma mater | University of Copenhagen |

| Doctoral advisor | Christian Christiansen |

| Other academic advisors | J. J. Thomson Ernest Rutherford |

| Doctoral students | Hendrik Anthony Kramers |

| Known for | |

| Influences | |

| Influenced |

|

| Notable awards |

|

| Spouse | Margrethe Nørlund (m. 1912; six children) |

| Signature

|

|

Niels Henrik David Bohr (Danish: [ˈnels ˈboɐ̯ˀ]; 7 October 1885 – 18 November 1962) was a Danish physicist who made foundational contributions to understanding atomic structure and quantum theory, for which he received the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1922. Bohr was also a philosopher and a promoter of scientific research.[1]

Bohr developed the Bohr model of the atom, in which he proposed that energy levels of electrons are discrete and that the electrons revolve in stable orbits around the atomic nucleus but can jump from one energy level (or orbit) to another. Although the Bohr model has been supplanted by other models, its underlying principles remain valid. He conceived the principle of complementarity: that items could be separately analysed in terms of contradictory properties, like behaving as a wave or a stream of particles. The notion of complementarity dominated Bohr's thinking in both science and philosophy.

Bohr founded the Institute of Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen, now known as the Niels Bohr Institute, which opened in 1920. Bohr mentored and collaborated with physicists including Hans Kramers, Oskar Klein, George de Hevesy and Werner Heisenberg. He predicted the existence of a new zirconium-like element, which was named hafnium, after the Latin name for Copenhagen, where it was discovered. Later, the element bohrium was named after him.

During the 1930s, Bohr helped refugees from Nazism. After Denmark was occupied by the Germans, he had a famous meeting with Heisenberg, who had become the head of the German nuclear energy project. In September 1943, word reached Bohr that he was about to be arrested by the Germans, and he fled to Sweden. From there, he was flown to Britain, where he joined the British Tube Alloys nuclear weapons project, and was part of the British mission to the Manhattan Project. After the war, Bohr called for international cooperation on nuclear energy. He was involved with the establishment of CERN[2] and the Research Establishment Risø of the Danish Atomic Energy Commission, and became the first chairman of the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics in 1957.

Early years

Niels Bohr was born in Copenhagen, Denmark, on 7 October 1885, the second of three children of Christian Bohr,[3][4] a professor of physiology at the University of Copenhagen, and Ellen Adler Bohr, who came from a wealthy Danish Jewish family prominent in banking and parliamentary circles.[5] He had an elder sister, Jenny, and a younger brother Harald.[3] Jenny became a teacher,[4] while Harald became a mathematician and Olympic footballer who played for the Danish national team at the 1908 Summer Olympics in London. Niels was a passionate footballer as well, and the two brothers played several matches for the Copenhagen-based Akademisk Boldklub (Academic Football Club), with Niels as goalkeeper.[6]Bohr was educated at Gammelholm Latin School, starting when he was seven.[7] In 1903, Bohr enrolled as an undergraduate at Copenhagen University. His major was physics, which he studied under Professor Christian Christiansen, the university's only professor of physics at that time. He also studied astronomy and mathematics under Professor Thorvald Thiele, and philosophy under Professor Harald Høffding, a friend of his father.[8][9]

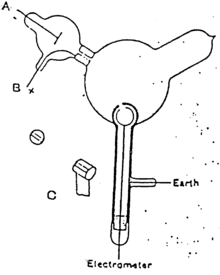

In 1905, a gold medal competition was sponsored by the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters to investigate a method for measuring the surface tension of liquids that had been proposed by Lord Rayleigh in 1879. This involved measuring the frequency of oscillation of the radius of a water jet. Bohr conducted a series of experiments using his father's laboratory in the university; the university itself had no physics laboratory. To complete his experiments, he had to make his own glassware, creating test tubes with the required elliptical cross-sections. He went beyond the original task, incorporating improvements into both Rayleigh's theory and his method, by taking into account the viscosity of the water, and by working with finite amplitudes instead of just infinitesimal ones. His essay, which he submitted at the last minute, won the prize. He later submitted an improved version of the paper to the Royal Society in London for publication in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society.[10][11][9][12]

Harald became the first of the two Bohr brothers to earn a master's degree, which he earned for mathematics in April 1909. Niels took another nine months to earn his. Students had to submit a thesis on a subject assigned by their supervisor. Bohr's supervisor was Christiansen, and the topic he chose was the electron theory of metals. Bohr subsequently elaborated his master's thesis into his much-larger Doctor of Philosophy (dr. phil.) thesis. He surveyed the literature on the subject, settling on a model postulated by Paul Drude and elaborated by Hendrik Lorentz, in which the electrons in a metal are considered to behave like a gas. Bohr extended Lorentz's model, but was still unable to account for phenomena like the Hall effect, and concluded that electron theory could not fully explain the magnetic properties of metals. The thesis was accepted in April 1911, and Bohr conducted his formal defence on 13 May. Harald had received his doctorate the previous year.[13] Bohr's thesis was groundbreaking, but attracted little interest outside Scandinavia because it was written in Danish, a Copenhagen University requirement at the time. In 1921, the Dutch physicist Hendrika Johanna van Leeuwen would independently derive a theorem from Bohr's thesis that is today known as the Bohr–van Leeuwen theorem.[14]

In 1910, Bohr met Margrethe Nørlund, the sister of the mathematician Niels Erik Nørlund.[15] Bohr resigned his membership in the Church of Denmark on 16 April 1912, and he and Margrethe were married in a civil ceremony at the town hall in Slagelse on 1 August. Years later, his brother Harald similarly left the church before getting married.[16] Niels and Margrethe had six sons.[17] The oldest, Christian, died in a boating accident in 1934,[18] and another, Harald, died from childhood meningitis.[17] Aage Bohr became a successful physicist, and in 1975 was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics, like his father. Hans Henrik became a physician; Erik, a chemical engineer; and Ernest, a lawyer.[19] Like his uncle Harald, Ernest Bohr became an Olympic athlete, playing field hockey for Denmark at the 1948 Summer Olympics in London.[20]

Physics

Bohr model

In 1911, Bohr travelled to England. At the time, it was where most of the theoretical work on the structure of atoms and molecules was being done.[21] He met J. J. Thomson of the Cavendish Laboratory and Trinity College, Cambridge. He attended lectures on electromagnetism given by James Jeans and Joseph Larmor, and did some research on cathode rays, but failed to impress Thomson.[22][23] He had more success with younger physicists like the Australian William Lawrence Bragg,[24] and New Zealand's Ernest Rutherford, whose 1911 Rutherford model of the atom had challenged Thomson's 1904 plum pudding model.[25] Bohr received an invitation from Rutherford to conduct post-doctoral work at Victoria University of Manchester,[26] where Bohr met George de Hevesy and Charles Galton Darwin (whom Bohr referred to as "the grandson of the real Darwin").[27]Bohr returned to Denmark in July 1912 for his wedding, and travelled around England and Scotland on his honeymoon. On his return, he became a privatdocent at the University of Copenhagen, giving lectures on thermodynamics. Martin Knudsen put Bohr's name forward for a docent, which was approved in July 1913, and Bohr then began teaching medical students.[28] His three papers, which later became famous as "the trilogy",[26] were published in Philosophical Magazine in July, September and November of that year.[29][30][31][32] He adapted Rutherford's nuclear structure to Max Planck's quantum theory and so created his Bohr model of the atom.[30]

Planetary models of atoms were not new, but Bohr's treatment was.[33] Taking the 1912 paper by Darwin on the role of electrons in the interaction of alpha particles with a nucleus as his starting point,[34][35] he advanced the theory of electrons travelling in orbits around the atom's nucleus, with the chemical properties of each element being largely determined by the number of electrons in the outer orbits of its atoms.[36] He introduced the idea that an electron could drop from a higher-energy orbit to a lower one, in the process emitting a quantum of discrete energy. This became a basis for what is now known as the old quantum theory.[37]

The Bohr model of the hydrogen atom. A negatively charged electron, confined to an atomic orbital, orbits a small, positively charged nucleus; a quantum jump between orbits is accompanied by an emitted or absorbed amount of electromagnetic radiation.

The evolution of atomic models in the 20th century: Thomson, Rutherford, Bohr, Heisenberg/Schrödinger

In 1885, Johann Balmer had come up with his Balmer series to describe the visible spectral lines of a hydrogen atoms:

The model's first hurdle was the Pickering series, lines which did not fit Balmer's formula. When challenged on this by Alfred Fowler, Bohr replied that they were caused by ionised helium, helium atoms with only one electron. The Bohr model was found to work for such ions.[39] Many older physicists, like Thomson, Rayleigh and Hendrik Lorentz, did not like the trilogy, but the younger generation, including Rutherford, David Hilbert, Albert Einstein, Max Born and Arnold Sommerfeld saw it as a breakthrough.[40][41] The trilogy's acceptance was entirely due to its ability to explain phenomena which stymied other models, and to predict results that were subsequently verified by experiments.[42] Today, the Bohr model of the atom has been superseded, but is still the best known model of the atom, as it often appears in high school physics and chemistry texts.[43]

Bohr did not enjoy teaching medical students. He decided to return to Manchester, where Rutherford had offered him a job as a reader in place of Darwin, whose tenure had expired. Bohr accepted. He took a leave of absence from the University of Copenhagen, which he started by taking a holiday in Tyrol with his brother Harald and aunt Hanna Adler. There, he visited the University of Göttingen and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, where he met Sommerfeld and conducted seminars on the trilogy. The First World War broke out while they were in Tyrol, greatly complicating the trip back to Denmark and Bohr's subsequent voyage with Margrethe to England, where he arrived in October 1914. They stayed until July 1916, by which time he had been appointed to the Chair of Theoretical Physics at the University of Copenhagen, a position created especially for him. His docentship was abolished at the same time, so he still had to teach physics to medical students. New professors were formally introduced to King Christian X, who expressed his delight at meeting such a famous football player.[44]

Institute of Physics

In April 1917, Bohr began a campaign to establish an Institute of Theoretical Physics. He gained the support of the Danish government and the Carlsberg Foundation, and sizeable contributions were also made by industry and private donors, many of them Jewish. Legislation establishing the Institute was passed in November 1918. Now known as the Niels Bohr Institute, it opened its doors on 3 March 1921 with Bohr as its director. His family moved into an apartment on the first floor.[45][46] Bohr's institute served as a focal point for researchers into quantum mechanics and related subjects in the 1920s and 1930s, when most of the world's best known theoretical physicists spent some time in his company. Early arrivals included Hans Kramers from the Netherlands, Oskar Klein from Sweden, George de Hevesy from Hungary, Wojciech Rubinowicz from Poland and Svein Rosseland from Norway. Bohr became widely appreciated as their congenial host and eminent colleague.[47][48] Klein and Rosseland produced the Institute's first paper even before it opened.[46]The Bohr model worked well for hydrogen, but could not explain more complex elements. By 1919, Bohr was moving away from the idea that electrons orbited the nucleus, and he developed heuristics to describe them. The rare earth elements posed a particular classification problem for chemists, because they were so chemically similar.

An important development came in 1924 with Wolfgang Pauli's discovery of the Pauli exclusion principle, which put Bohr's models on a firm theoretical footing. Bohr was then able to declare that the as-yet-undiscovered element 72 was not a rare earth element, but an element with chemical properties similar to those of zirconium. He was immediately challenged by the French chemist Georges Urbain, who claimed to have discovered a rare earth element 72, which he called "celtium". At the Institute in Copenhagen, Dirk Coster and George de Hevesy took up the challenge of proving Bohr right and Urbain wrong. Starting with a clear idea of the chemical properties of the unknown element greatly simplified the search process. They went through samples from Copenhagen's Museum of Mineralogy looking for a zirconium-like element, and soon found it. The element, which they named hafnium, Hafnia being the Latin name for Copenhagen, turned out to be more common than gold.[49][50]

In 1922, Bohr was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics "for his services in the investigation of the structure of atoms and of the radiation emanating from them".[51] The award thus recognised both the Trilogy and his early leading work in the emerging field of quantum mechanics. For his Nobel lecture, Bohr gave his audience a comprehensive survey of what was then known about the structure of the atom, including the correspondence principle, which he had formulated. This states that the behaviour of systems described by quantum theory reproduces classical physics in the limit of large quantum numbers.[52]

The discovery of Compton scattering by Arthur Holly Compton in 1923 convinced most physicists that light was composed of photons, and that energy and momentum were conserved in collisions between electrons and photons. In 1924, Bohr, Kramers and John C. Slater, an American physicist working at the Institute in Copenhagen, proposed the Bohr–Kramers–Slater theory (BKS). It was more a programme than a full physical theory, as the ideas it developed were not worked out quantitatively. BKS theory became the final attempt at understanding the interaction of matter and electromagnetic radiation on the basis of the old quantum theory, in which quantum phenomena were treated by imposing quantum restrictions on a classical wave description of the electromagnetic field.[53][54]

Modelling atomic behaviour under incident electromagnetic radiation using "virtual oscillators" at the absorption and emission frequencies, rather than the (different) apparent frequencies of the Bohr orbits, led Max Born, Werner Heisenberg and Kramers to explore different mathematical models. They led to the development of matrix mechanics, the first form of modern quantum mechanics. The BKS theory also generated discussion of, and renewed attention to, difficulties in the foundations of the old quantum theory.[55] The most provocative element of BKS – that momentum and energy would not necessarily be conserved in each interaction, but only statistically – was soon shown to be in conflict with experiments conducted by Walther Bothe and Hans Geiger.[56] In the light of these results, Bohr informed Darwin, "there is nothing else to do than to give our revolutionary efforts as honourable a funeral as possible."[57]

Quantum mechanics

The introduction of spin by George Uhlenbeck and Samuel Goudsmit in November 1925 was a milestone. The next month, Bohr travelled to Leiden to attend celebrations of the 50th anniversary of Hendrick Lorentz receiving his doctorate. When his train stopped in Hamburg, he was met by Wolfgang Pauli and Otto Stern, who asked for his opinion of the spin theory. Bohr pointed out that he had concerns about the interaction between electrons and magnetic fields. When he arrived in Leiden, Paul Ehrenfest and Albert Einstein informed Bohr that Einstein had resolved this problem using relativity. Bohr then had Uhlenbeck and Goudsmit incorporate this into their paper. Thus, when he met Werner Heisenberg and Pascual Jordan in Göttingen on the way back, he had become, in his own words, "a prophet of the electron magnet gospel".[58]

1927 Solvay Conference in Brussels, October 1927. Bohr is on the right in the middle row, next to Max Born.

Heisenberg first came to Copenhagen in 1924, then returned to Göttingen in June 1925, shortly thereafter developing the mathematical foundations of quantum mechanics. When he showed his results to Max Born in Göttingen, Born realised that they could best be expressed using matrices. This work attracted the attention of the British physicist Paul Dirac,[59] who came to Copenhagen for six months in September 1926. Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger also visited in 1926. His attempt at explaining quantum physics in classical terms using wave mechanics impressed Bohr, who believed it contributed "so much to mathematical clarity and simplicity that it represents a gigantic advance over all previous forms of quantum mechanics".[60]

When Kramers left the Institute in 1926 to take up a chair as professor of theoretical physics at the Utrecht University, Bohr arranged for Heisenberg to return and take Kramers's place as a lektor at the University of Copenhagen.[61] Heisenberg worked in Copenhagen as a university lecturer and assistant to Bohr from 1926 to 1927,[62]

Bohr became convinced that light behaved like both waves and particles, and in 1927, experiments confirmed the de Broglie hypothesis that matter (like electrons) also behaved like waves.[63] He conceived the philosophical principle of complementarity: that items could have apparently mutually exclusive properties, such as being a wave or a stream of particles, depending on the experimental framework.[64] He felt that that it was not fully understood by professional philosophers.[65]

In Copenhagen in 1927 Heisenberg developed his uncertainty principle,[66] which Bohr embraced. In a paper he presented at the Volta Conference at Como in September 1927, he demonstrated that the uncertainty principle could be derived from classical arguments, without quantum terminology or matrices.[66] Einstein preferred the determinism of classical physics over the probabilistic new quantum physics to which he himself had contributed.

Philosophical issues that arose from the novel aspects of quantum mechanics became widely celebrated subjects of discussion. Einstein and Bohr had good-natured arguments over such issues throughout their lives.[67]

In 1914, Carl Jacobsen, the heir to Carlsberg breweries, bequeathed his mansion to be used for life by the Dane who had made the most prominent contribution to science, literature or the arts, as an honorary residence (Danish: Æresbolig). Harald Høffding had been the first occupant, and upon his death in July 1931, the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters gave Bohr occupancy. He and his family moved there in 1932.[68] He was elected president of the Academy on 17 March 1939.[69]

By 1929, the phenomenon of beta decay prompted Bohr to again suggest that the law of conservation of energy be abandoned, but Enrico Fermi's hypothetical neutrino and the subsequent 1932 discovery of the neutron provided another explanation. This prompted Bohr to create a new theory of the compound nucleus in 1936, which explained how neutrons could be captured by the nucleus. In this model, the nucleus could be deformed like a drop of liquid.

He worked on this with a new collaborator, the Danish physicist Fritz Kalckar, who died suddenly in 1938.[70][71]

The discovery of nuclear fission by Otto Hahn in December 1938 (and its theoretical explanation by Lise Meitner) generated intense interest among physicists. Bohr brought the news to the United States where he opened the Fifth Washington Conference on Theoretical Physics with Fermi on 26 January 1939.[72] When Bohr told George Placzek that this resolved all the mysteries of transuranic elements, Placzek told him that one remained: the neutron capture energies of uranium did not match those of its decay. Bohr thought about it for a few minutes and then announced to Placzek, Léon Rosenfeld and John Wheeler that "I have understood everything."[73] Based on his liquid drop model of the nucleus, Bohr concluded that it was the uranium-235 isotope and not the more abundant uranium-238 that was primarily responsible for fission. In April 1940, John R. Dunning demonstrated that Bohr was correct.[72] In the meantime, Bohr and Wheeler developed a theoretical treatment which they published in a September 1939 paper on "The Mechanism of Nuclear Fission".[74]

Philosophy

Bohr read the 19th-century Danish Christian existentialist philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard. Richard Rhodes argued in The Making of the Atomic Bomb that Bohr was influenced by Kierkegaard through Høffding.[75] In 1909, Bohr sent his brother Kierkegaard's Stages on Life's Way as a birthday gift. In the enclosed letter, Bohr wrote, "It is the only thing I have to send home; but I do not believe that it would be very easy to find anything better ... I even think it is one of the most delightful things I have ever read." Bohr enjoyed Kierkegaard's language and literary style, but mentioned that he had some disagreement with Kierkegaard's philosophy.[76] Some of Bohr's biographers suggested that this disagreement stemmed from Kierkegaard's advocacy of Christianity, while Bohr was an atheist.[77][78][79]There has been some dispute over the extent to which Kierkegaard influenced Bohr's philosophy and science. David Favrholdt argued that Kierkegaard had minimal influence over Bohr's work, taking Bohr's statement about disagreeing with Kierkegaard at face value,[80] while Jan Faye argued that one can disagree with the content of a theory while accepting its general premises and structure.[81][76]

Nazism and Second World War

The rise of Nazism in Germany prompted many scholars to flee their countries, either because they were Jewish or because they were political opponents of the Nazi regime. In 1933, the Rockefeller Foundation created a fund to help support refugee academics, and Bohr discussed this programme with the President of the Rockefeller Foundation, Max Mason, in May 1933 during a visit to the United States. Bohr offered the refugees temporary jobs at the Institute, provided them with financial support, arranged for them to be awarded fellowships from the Rockefeller Foundation, and ultimately found them places at institutions around the world. Those that he helped included Guido Beck, Felix Bloch, James Franck, George de Hevesy, Otto Frisch, Hilde Levi, Lise Meitner, George Placzek, Eugene Rabinowitch, Stefan Rozental, Erich Ernst Schneider, Edward Teller, Arthur von Hippel and Victor Weisskopf.[82]In April 1940, early in the Second World War, Nazi Germany invaded and occupied Denmark.[83] To prevent the Germans from discovering Max von Laue's and James Franck's gold Nobel medals, Bohr had de Hevesy dissolve them in aqua regia. In this form, they were stored on a shelf at the Institute until after the war, when the gold was precipitated and the medals re-struck by the Nobel Foundation. Bohr kept the Institute running, but all the foreign scholars departed.[84]

Meeting with Heisenberg

Bohr was aware of the possibility of using uranium-235 to construct an atomic bomb, referring to it in lectures in Britain and Denmark shortly before and after the war started, but he did not believe that it was technically feasible to extract a sufficient quantity of uranium-235.[85] In September 1941, Heisenberg, who had become head of the German nuclear energy project, visited Bohr in Copenhagen. During this meeting the two men took a private moment outside, the content of which has caused much speculation, as both gave differing accounts. According to Heisenberg, he began to address nuclear energy, morality and the war, to which Bohr seems to have reacted by terminating the conversation abruptly while not giving Heisenberg hints about his own opinions.[86] Ivan Supek, one of Heisenberg's students and friends, claimed that the main subject of the meeting was Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, who had proposed trying to persuade Bohr to mediate peace between Britain and Germany.[87]

In 1957, Heisenberg wrote to Robert Jungk, who was then working on the book Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists. Heisenberg explained that he had visited Copenhagen to communicate to Bohr the views of several German scientists, that production of a nuclear weapon was possible with great efforts, and this raised enormous responsibilities on the world's scientists on both sides.[88] When Bohr saw Jungk's depiction in the Danish translation of the book, he drafted (but never sent) a letter to Heisenberg, stating that he never understood the purpose of Heisenberg's visit, was shocked by Heisenberg's opinion that Germany would win the war, and that atomic weapons could be decisive.[89]

Michael Frayn's 1998 play Copenhagen explores what might have happened at the 1941 meeting between Heisenberg and Bohr.[90] A BBC television film version of the play was first screened on 26 September 2002, with Stephen Rea as Bohr, and Daniel Craig as Heisenberg. The same meeting had previously been dramatised by the BBC's Horizon science documentary series in 1992, with Anthony Bate as Bohr, and Philip Anthony as Heisenberg.[91]

Manhattan Project

In September 1943, word reached Bohr and his brother Harald that the Nazis considered their family to be Jewish, since their mother, Ellen Adler Bohr, had been a Jew, and that they were therefore in danger of being arrested. The Danish resistance helped Bohr and his wife escape by sea to Sweden on 29 September.[92][93] The next day, Bohr persuaded King Gustaf V of Sweden to make public Sweden's willingness to provide asylum to Jewish refugees. On 2 October 1943, Swedish radio broadcast that Sweden was ready to offer asylum, and the mass rescue of the Danish Jews by their countrymen followed swiftly thereafter. Some historians claim that Bohr's actions led directly to the mass rescue, while others say that, though Bohr did all that he could for his countrymen, his actions were not a decisive influence on the wider events.[93][94][95][96] Eventually, over 7,000 Danish Jews escaped to Sweden.[97]When the news of Bohr's escape reached Britain, Lord Cherwell sent a telegram to Bohr asking him to come to Britain. Bohr arrived in Scotland on 6 October in a de Havilland Mosquito operated by British Overseas Airways Corporation. The Mosquitos were unarmed high-speed bomber aircraft that had been converted to carry small, valuable cargoes or important passengers. By flying at high speed and high altitude, they could cross German-occupied Norway, and yet avoid German fighters. Bohr, equipped with parachute, flying suit and oxygen mask, spent the three-hour flight lying on a mattress in the aircraft's bomb bay.[98] During the flight, Bohr did not wear his flying helmet as it was too small, and consequently did not hear the pilot's intercom instruction to turn on his oxygen supply when the aircraft climbed to high altitude to overfly Norway. He passed out from oxygen starvation and only revived when the aircraft descended to lower altitude over the North Sea.[99][100][101] Bohr's son Aage followed his father to Britain on another flight a week later, and became his personal assistant.[102][103]

Bohr was warmly received by James Chadwick and Sir John Anderson, but for security reasons Bohr was kept out of sight. He was given an apartment at St James's Palace and an office with the British Tube Alloys nuclear weapons development team. Bohr was astonished at the amount of progress that had been made.[102][103] Chadwick arranged for Bohr to visit the United States as a Tube Alloys consultant, with Aage as his assistant.[104] On 8 December 1943, Bohr arrived in Washington, D.C., where he met with the director of the Manhattan Project, Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr. He visited Einstein and Pauli at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, and went to Los Alamos in New Mexico, where the nuclear weapons were being designed.[105] For security reasons, he went under the name of "Nicholas Baker" in the United States, while Aage became "James Baker".[106] In May 1944 the Danish resistance newspaper De frie Danske reported that they had learned that 'the famous son of Denmark Professor Niels Bohr' in October the previous year had fled his country via Sweden to London and from there travelled to Moscow from where he could be assumed to support the war effort.[107]

Bohr did not remain at Los Alamos, but paid a series of extended visits over the course of the next two years. Robert Oppenheimer credited Bohr with acting "as a scientific father figure to the younger men", most notably Richard Feynman.[108] Bohr is quoted as saying, "They didn't need my help in making the atom bomb."[109]

Oppenheimer gave Bohr credit for an important contribution to the work on modulated neutron initiators. "This device remained a stubborn puzzle," Oppenheimer noted, "but in early February 1945 Niels Bohr clarified what had to be done."[108]

Bohr recognised early that nuclear weapons would change international relations. In April 1944, he received a letter from Peter Kapitza, written some months before when Bohr was in Sweden, inviting him to come to the Soviet Union. The letter convinced Bohr that the Soviets were aware of the Anglo-American project, and would strive to catch up. He sent Kapitza a non-committal response, which he showed to the authorities in Britain before posting.[110] Bohr met Churchill on 16 May 1944, but found that "we did not speak the same language".[111]

Churchill disagreed with the idea of openness towards the Russians to the point that he wrote in a letter: "It seems to me Bohr ought to be confined or at any rate made to see that he is very near the edge of mortal crimes."[112]

Oppenheimer suggested that Bohr visit President Franklin D. Roosevelt to convince him that the Manhattan Project should be shared with the Soviets in the hope of speeding up its results. Bohr's friend, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter, informed President Roosevelt about Bohr's opinions, and a meeting between them took place on 26 August 1944. Roosevelt suggested that Bohr return to the United Kingdom to try to win British approval.[113][114] When Churchill and Roosevelt met at Hyde Park on 19 September 1944, they rejected the idea of informing the world about the project, and the aide-mémoire of their conversation contained a rider that "enquiries should be made regarding the activities of Professor Bohr and steps taken to ensure that he is responsible for no leakage of information, particularly to the Russians".[115]

In June 1950, Bohr addressed an "Open Letter" to the United Nations calling for international cooperation on nuclear energy.[116][117][118] In the 1950s, after the Soviet Union's first nuclear weapon test, the International Atomic Energy Agency was created along the lines of Bohr's suggestion.[119] In 1957 he received the first ever Atoms for Peace Award.[120]

Later years

With the war ended, Bohr returned to Copenhagen on 25 August 1945, and was re-elected President of the Royal Danish Academy of Arts and Sciences on 21 September.[121] At a memorial meeting of the Academy on 17 October 1947 for King Christian X, who had died in April, the new king, Frederick IX, announced that he was conferring the Order of the Elephant on Bohr. This award was normally awarded only to royalty and heads of state, but the king said that it honoured not just Bohr personally, but Danish science.[122][123] Bohr designed his own coat of arms which featured a taijitu (symbol of yin and yang) and a motto in Latin: contraria sunt complementa, "opposites are complementary".[124][123]

The Second World War demonstrated that science, and physics in particular, now required considerable financial and material resources. To avoid a brain drain to the United States, twelve European countries banded together to create CERN, a research organisation along the lines of the national laboratories in the United States, designed to undertake Big Science projects beyond the resources of any one of them alone. Questions soon arose regarding the best location for the facilities. Bohr and Kramers felt that the Institute in Copenhagen would be the ideal site. Pierre Auger, who organised the preliminary discussions, disagreed; he felt that both Bohr and his Institute were past their prime, and that Bohr's presence would overshadow others. After a long debate, Bohr pledged his support to CERN in February 1952, and Geneva was chosen as the site in October. The CERN Theory Group was based in

Copenhagen until their new accommodation in Geneva was ready in 1957.[125] Victor Weisskopf, who later became the Director General of CERN, summed up Bohr's role, saying that "there were other personalities who started and conceived the idea of CERN. The enthusiasm and ideas of the other people would not have been enough, however, if a man of his stature had not supported it."[126][127]

Meanwhile, Scandinavian countries formed the Nordic Institute for Theoretical Physics in 1957, with Bohr as its chairman. He was also involved with the founding of the Research Establishment Risø of the Danish Atomic Energy Commission, and served as its first chairman from February 1956.[128]

Bohr died of heart failure at his home in Carlsberg on 18 November 1962.[129] He was cremated, and his ashes were buried in the family plot in the Assistens Cemetery in the Nørrebro section of Copenhagen, along with those of his parents, his brother Harald, and his son Christian. Years later, his wife's ashes were also interred there.[130] On 7 October 1965, on what would have been his 80th birthday, the Institute was officially renamed to what it had been called unofficially for many years: the Niels Bohr Institute.[131][132]

Accolades

Bohr received numerous honours and accolades. In addition to the Nobel Prize, he received the Hughes Medal in 1921, the Matteucci Medal in 1923,[133] the Franklin Medal in 1926,[134] the Copley Medal in 1938, the Order of the Elephant in 1947, the Atoms for Peace Award in 1957 and the Sonning Prize in 1961.[133] The Bohr model's semicentennial was commemorated in Denmark on 21 November 1963 with a postage stamp depicting Bohr, the hydrogen atom and the formula for the difference of any two hydrogen energy levels: . Several other countries have also issued postage stamps depicting Bohr.[135] In 1997, the Danish National Bank began circulating the 500-krone banknote with the portrait of Bohr smoking a pipe.[136][137] An asteroid, 3948 Bohr, was named after him,[138] as was a lunar crater (Bohr (crater)),[133] and bohrium, the chemical element with atomic number 107.[139]

. Several other countries have also issued postage stamps depicting Bohr.[135] In 1997, the Danish National Bank began circulating the 500-krone banknote with the portrait of Bohr smoking a pipe.[136][137] An asteroid, 3948 Bohr, was named after him,[138] as was a lunar crater (Bohr (crater)),[133] and bohrium, the chemical element with atomic number 107.[139]Bibliography

- Bohr, Niels (2008). Nielsen, J. Rud, ed. Volume 1: Early Work (1905–1911). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Hoyer, Ulrich, ed. Volume 2: Work on Atomic Physics (1912–1917). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Nielsen, J. Rud, ed. Volume 3: The Correspondence Principle (1918–1923). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Nielsen, J. Rud, ed. Volume 4: The Periodic System (1920–1923). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Stolzenburg, Klaus, ed. Volume 5: The Emergence of Quantum Mechanics (mainly 1924–1926). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Kalckar, Jørgen, ed. Volume 6: Foundations of Quantum Physics I (1926–1932). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Kalckar, Jørgen, ed. Volume 7: Foundations of Quantum Physics I (1933–1958). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Thorsen, Jens, ed. Volume 8: The Penetration of Charged Particles Through Matter (1912–1954). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Peierls, Rudolf, ed. Volume 9: Nuclear Physics (1929–1952). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Favrholdt, David, ed. Volume 10: Complementarity Beyond Physics (1928–1962). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Aaserud, Finn, ed. Volume 11: The Political Arena (1934–1961). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Aaserud, Finn, ed. Volume 12: Popularization and People (1911–1962). Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.

- —— (2008). Aaserud, Finn, ed. Volume 13: Cumulative Subject Index. Niels Bohr Collected Works. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-444-53286-2. OCLC 272382249.