Global governance is not a singular system. There is no "world government" but the many different regimes of global governance do have commonalities:

While the contemporary system of global political relations is not integrated, the relation between the various regimes of global governance is not insignificant, and the system does have a common dominant organizational form. The dominant mode of organization today is bureaucratic rational—regularized, codified and rational. It is common to all modern regimes of political power and frames the transition from classical sovereignty to what David Held describes as the second regime of sovereignty—liberal international sovereignty.

Definition

The term world governance is broadly used to designate all regulations intended for organization and centralization of human societies on a global scale. The Forum for a new World Governance defines world governance simply as "collective management of the planet".Traditionally, government has been associated with "governing," or with political authority, institutions, and, ultimately, control. Governance denotes a process through which institutions coordinate and control independent social relations, and that have the ability to enforce, by force, their decisions. However, authors like James Rosenau have also used "governance" to denote the regulation of interdependent relations in the absence of an overarching political authority, such as in the international system. Some now speak of the development of "global public policy".

Adil Najam, a scholar on the subject at the Pardee School of Global Studies, Boston University has defined global governance simply as "the management of global processes in the absence of global government." According to Thomas G. Weiss, director of the Ralph Bunche Institute for International Studies at the Graduate Center (CUNY) and editor (2000–05) of the journal Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, "'Global governance'—which can be good, bad, or indifferent—refers to concrete cooperative problem-solving arrangements, many of which increasingly involve not only the United Nations of states but also 'other UNs,' namely international secretariats and other non-state actors." In other words, global governance refers to the way in which global affairs are managed.

The definition is flexible in scope, applying to general subjects such as global security and order or to specific documents and agreements such as the World Health Organization's Code on the Marketing of Breast Milk Substitutes. The definition applies whether the participation is bilateral (e.g. an agreement to regulate usage of a river flowing in two countries), function-specific (e.g. a commodity agreement), regional (e.g. the Treaty of Tlatelolco), or global (e.g. the Non-Proliferation Treaty). These "cooperative problem-solving arrangements" may be formal, taking the shape of laws or formally constituted institutions for a variety of actors (such as state authorities, intergovernmental organizations (IGOs), non-governmental organizations (NGOs), private sector entities, other civil society actors, and individuals) to manage collective affairs. They may also be informal (as in the case of practices or guidelines) or ad hoc entities (as in the case of coalitions).

However, a single organization may take the nominal lead on an issue, for example the World Trade Organization (WTO) in world trade affairs. Therefore, global governance is thought to be an international process of consensus-forming which generates guidelines and agreements that affect national governments and international corporations. Examples of such consensus would include WHO policies on health issues.

In short, global governance may be defined as "the complex of formal and informal institutions, mechanisms, relationships, and processes between and among states, markets, citizens and organizations, both inter- and non-governmental, through which collective interests on the global plane are articulated, Duties, obligations and privileges are established, and differences are mediated through educated professionals."

Titus Alexander, author of Unravelling Global Apartheid, an Overview of World Politics, has described the current institutions of global governance as a system of global apartheid, with numerous parallels with minority rule in the formal and informal structures of South Africa before 1991.

Usage

The dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 marked the end of a long period of international history based on a policy of balance of powers. Since this historic event, the planet has entered a phase of geostrategic breakdown. The national-security model, for example, while still in place for most governments, is gradually giving way to an emerging collective conscience that extends beyond the restricted framework it represents.The post-Cold War world of the 1990s saw a new paradigm emerge based on a number of issues:

- The growing idea of globalization as a significant theme and the subsequent weakening of nation-states, points to a prospect of transferring to a global level of regulatory instruments. Upon the model that regulation was no longer working effectively at the national or regional levels;

- An intensification of environmental concerns, which received multilateral endorsement at the Earth Summit. The Summit issues, relating to the climate and biodiversity, symbolized a new approach that was soon to be expressed conceptually by the term Global Commons;

- The emergence of conflicts over standards: trade and the environment, trade and property rights, trade and public health. These conflicts continued the traditional debate over the social effects of macroeconomic stabilization policies, and raised the question of arbitration among equally legitimate objectives in a compartmentalized governance system where the major areas of interdependence are each entrusted to a specialized international institution. Although often limited in scope, these conflicts are nevertheless symbolically powerful, as they raise the question of the principles and institutions of arbitration;

- An increased questioning of international standards and institutions by developing countries, which, having entered the global economy, find it hard to accept that industrialized countries hold onto power and give preference to their own interests. The challenge also comes from civil society, which considers that the international governance system has become the real seat of power and which rejects both its principles and procedures. Although these two lines of criticism often have conflicting beliefs and goals, they have been known to join in order to oppose the dominance of developed countries and major institutions, as demonstrated symbolically by the failure of the World Trade Organization Ministerial Conference of 1999.

Technique

Global governance can be roughly divided into four stages:- agenda-setting;

- policymaking;

- implementation and enforcement; and

- evaluation, monitoring, and adjudication.

Themes

In its initial phase, world governance was able to draw on themes inherited from geopolitics and the theory of international relations, such as peace, defense, geostrategy, diplomatic relations, and trade relations. But as globalization progresses and the number of interdependences increases, the global level is also highly relevant to a far wider range of subjects. Following are a number of examples.Environmental governance and managing the planet

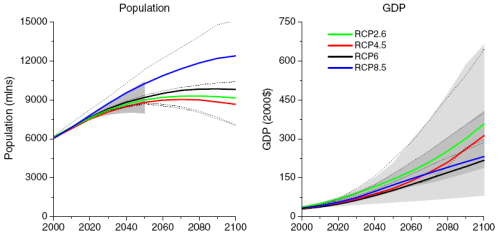

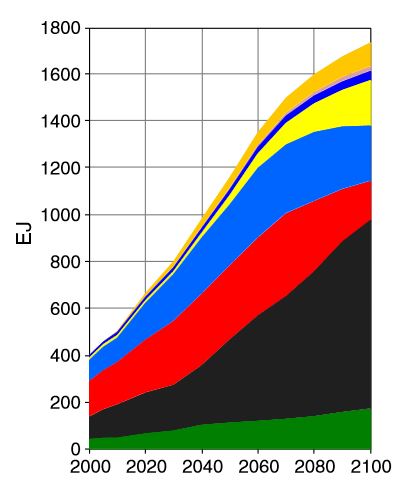

"The crisis brought about by the accelerated pace and the probably irreversible character of the effect of human activities on nature requires collective answers from governments and citizens. Nature ignores political and social barriers, and the global dimension of the crisis cancels the effects of any action initiated unilaterally by state governments or sectoral institutions, however powerful they may be. Climate change, ocean and air pollution, nuclear risks and those related to genetic manipulation, the reduction and extinction of resources and biodiversity, and above all a development model that remains largely unquestioned globally are all among the various manifestations of this accelerated and probably irreversible effect.This effect is the factor, in the framework of globalization, that most challenges a system of states competing with each other to the exclusion of all others: among the different fields of global governance, environmental management is the most wanting in urgent answers to the crisis in the form of collective actions by the whole of the human community. At the same time, these actions should help to model and strengthen the progressive building of this community."

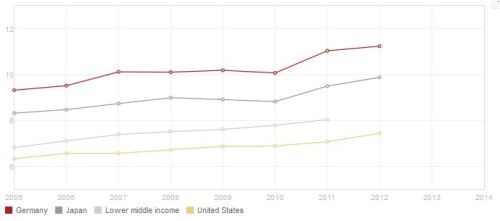

Proposals in this area have discussed the issue of how collective environmental action is possible. Many multilateral, environment-related agreements have been forged in the past 30 years, but their implementation remains difficult. There is also some discussion on the possibility of setting up an international organization that would centralize all the issues related to international environmental protection, such as the proposed World Environment Organization (WEO). The United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) could play this role, but it is a small-scale organization with a limited mandate. The question has given rise to two opposite views: the European Union, especially France and Germany, along with a number of NGOs, is in favor of creating a WEO; the United Kingdom, the USA, and most developing countries prefer opting for voluntary initiatives.

The International Institute for Sustainable Development proposes a "reform agenda" for global environmental governance. The main argument is that there seems to exist an unspoken but powerful consensus on the essential objectives of a system of global environmental governance. These goals would require top-quality leadership, a strong environmental policy based on knowledge, effective cohesion and coordination, good management of the institutions constituting the environmental governance system, and spreading environmental concerns and actions to other areas of international policy and action.

A World Environment Organisation

The focus of environmental issues shifted to climate change from 1992 onwards. Due to the transboundary nature of climate change, various calls have been made for a World Environment Organisation (WEO) (sometimes referred to as a Global Environment Organisation) to tackle this global problem on a global scale. At present, a single worldwide governing body with the powers to develop and enforce environmental policy does not exist. The idea for the creation of a WEO was discussed thirty years ago but is receiving fresh attention in the light of arguably disappointing outcomes from recent, ‘environmental mega-conferences’ (e.g.Rio Summit and Earth Summit 2002).Current global environmental governance

International environmental organisations do exist. The United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), created in 1972, coordinates the environmental activity of countries in the UN. UNEP and similar international environmental organisations are seen as not up to the task. They are criticised as being institutionally weak, fragmented, lacking in standing and providing non-optimal environmental protection. It has been stated that the current decentralised, poorly funded and strictly intergovernmental regime for global environmental issues is sub-standard. However, the creation of a WEO may threaten to undermine some of the more effective aspects of contemporary global environmental governance; notably its fragmented nature, from which flexibility stems. This also allows responses to be more effective and links to be forged across different domains. Even though the environment and climate change are framed as global issues, Levin states that ‘it is precisely at this level that government institutions are least effective and trust most delicate’ while Oberthur and Gehring argue that it would offer little more than institutional restructuring for its own sake.A World Environment Organisation and the World Trade Organisation

Many proposals for the creation of a WEO have emerged from the trade and environment debate. It has been argued that instead of creating a WEO to safeguard the environment, environmental issues should be directly incorporated into the World Trade Organization (WTO). The WTO has “had success in integrating trade agreements and opening up markets because it is able to apply legal pressure to nation states and resolve disputes”. Greece and Germany are currently in discussion about the possibility of solar energy being used to repay some of Greece’s debt after their economy crashed in 2010. This exchange of resources, if it is accepted, is an example of increased international cooperation and an instance where the WTO could embrace energy trade agreements. If the future holds similar trade agreements, then an environmental branch of the WTO would surely be necessary. However critics of a WTO/WEO arrangement say that this would neither concentrate on more directly addressing underlying market failures, nor greatly improve rule-making.The creation of a new agency, whether it be linked to the WTO or not, has now been endorsed by Renato Ruggiero, the former head of the World Trade Organization (WTO), as well as by the new WTO director-designate, Supachai Panitchpakdi. The debate over a global institutional framework for environmental issues will undoubtedly rumble on but at present there is little support for any one proposal.

Governance of the economy and of globalisation

The 2008 financial crisis may have undermined faith that laissez-faire capitalism will correct all serious financial malfunctioning on its own, as well as belief in the presumed independence of the economy from politics. It has been stated that, lacking in transparency and far from democratic, international financial institutions may be incapable of handling financial collapses. There are many who believe free-market capitalism may be incapable of forming the economic policy of a stable society, as it has been theorised that it can exacerbate inequalities.Nonetheless, the debate on the potential failings of the system has led the academic world to seek solutions. According to Tubiana and Severino, "refocusing the doctrine of international cooperation on the concept of public goods offers the possibility . . . of breaking the deadlock in international negotiations on development, with the perception of shared interests breathing new life into an international solidarity that is running out of steam."

Joseph Stiglitz argues that a number of global public goods should be produced and supplied to the populations, but are not, and that a number of global externalities should be taken into consideration, but are not. On the other hand, he contends, the international stage is often used to find solutions to completely unrelated problems under the protection of opacity and secrecy, which would be impossible in a national democratic framework.

On the subject of international trade, Susan George states that ". . . in a rational world, it would be possible to construct a trading system serving the needs of people in both North and South. . . . Under such a system, crushing third world debt and the devastating structural adjustment policies applied by the World Bank and the IMF would have been unthinkable, although the system would not have abolished capitalism."

Political and institutional governance

Building a responsible world governance that would make it possible to adapt the political organization of society to globalization implies establishing a democratic political legitimacy at every level: local, national, regional and global.Obtaining this legitimacy requires rethinking and reforming, all at the same time:

- the fuzzy maze of various international organizations, instituted mostly in the wake of World War II; what is needed is a system of international organizations with greater resources and a greater intervention capacity, more transparent, fairer, and more democratic;

- the Westphalian system, the very nature of states along with the role they play with regard to the other institutions, and their relations to each other; states will have to share part of their sovereignty with institutions and bodies at other territorial levels, and all with have to begin a major process to deepen democracy and make their organization more responsible;

- the meaning of citizen sovereignty in the different government systems and the role of citizens as political protagonists; there is a need to rethink the meaning of political representation and participation and to sow the seeds of a radical change of consciousness that will make it possible to move in the direction of a situation in which citizens, in practice, will play the leading role at every scale.

Governance of peace, security, and conflict resolution

Armed conflicts have changed in form and intensity since the Berlin wall came down in 1989. The events of 9/11, the wars in Afghanistan and in Iraq, and repeated terrorist attacks all show that conflicts can repercuss well beyond the belligerents directly involved. The major powers and especially the United States, have used war as a means of resolving conflicts and may well continue to do so. If many in the United States believe that fundamentalist Muslim networks are likely to continue to launch attacks, in Europe nationalist movements have proved to be the most persistent terrorist threat. The Global War on Terrorism arguably presents a form of emerging global governance in the sphere of security with the United States leading cooperation among the Western states, non-Western nations and international institutions. Beyer argues that participation in this form of 'hegemonic governance' is caused both by a shared identity and ideology with the US, as well as cost-benefit considerations. Pesawar school attack 2014 is a big challenge to us. Militants from the Pakistani Taliban have attacked an army-run school in Peshawar, killing 141 people, 132 of them children, the military say.At the same time, civil wars continue to break out across the world, particularly in areas where civil and human rights are not respected, such as Central and Eastern Africa and the Middle East. These and other regions remain deeply entrenched in permanent crises, hampered by authoritarian regimes, many of them being supported by the United States, reducing entire swathes of the population to wretched living conditions. The wars and conflicts we are faced with have a variety of causes: economic inequality, social conflict, religious sectarianism, Western imperialism, colonial legacies, disputes over territory and over control of basic resources such as water or land. They are all illustrations a deep-rooted crisis of world governance.

The resulting bellicose climate imbues international relations with competitive nationalism and contributes, in rich and poor countries alike, to increasing military budgets, siphoning off huge sums of public money to the benefit of the arms industry and military-oriented scientific innovation, hence fueling global insecurity. Of these enormous sums, a fraction would be enough to provide a permanent solution for the basic needs of the planet's population hence practically eliminating the causes of war and terrorism.

Andrée Michel argues that the arms race is not only proceeding with greater vigor, it is the surest means for Western countries to maintain their hegemony over countries of the South. Following the break-up of the Eastern bloc countries, she maintains, a strategy for the manipulation of the masses was set up with a permanent invention of an enemy (currently incarnated by Iraq, Iran, Libya, Syria, and North Korea) and by kindling fear and hate of others to justify perpetuating the Military–industrial complex and arms sales. The author also recalls that the "Big Five" at the UN who have the veto right are responsible for 85% of arms sales around the world.

Proposals for the governance of peace, security, and conflict resolution begin by addressing prevention of the causes of conflicts, whether economic, social, religious, political, or territorial. This requires assigning more resources to improving people's living conditions—health, accommodation, food, and work—and to education, including education in the values of peace, social justice, and unity and diversity as two sides of the same coin representing the global village.

Resources for peace could be obtained by regulating, or even reducing military budgets, which have done nothing but rise in the past recent years. This process could go hand in hand with plans for global disarmament and the conversion of arms industries, applied proportionally to all countries, including the major powers. Unfortunately, the warlike climate of the last decade has served to relegate all plans for global disarmament, even in civil-society debates, and to pigeonhole them as a long-term goal or even a Utopian vision. This is definitely a setback for the cause of peace and for humankind, but it is far from being a permanent obstacle.

International institutions also have a role to play in resolving armed conflicts. Small international rapid deployment units could intervene in these with an exclusive mandate granted by a reformed and democratic United Nations system or by relevant regional authorities such as the European Union. These units could be formed specifically for each conflict, using armies from several countries as was the case when the UNIFIL was reinforced during the 2006 Lebanon War. On the other hand, no national army would be authorized to intervene unilaterally outside its territory without a UN or regional mandate.

Another issue that is worth addressing concerns the legitimate conditions for the use of force and conduct during war. Jean-Réné Bachelet offers an answer with the conceptualization of a military ethics corresponding to the need for a "principle of humanity." The author defines this principle as follows: "All human beings, whatever their race, nationality, gender, age, opinion, or religion, belong to one same humanity, and every individual has an inalienable right to respect for his life, integrity, and dignity."

Governance of science, education, information, and communications

The World Trade Organization's (WTO) agenda of liberalizing public goods and services are related to culture, science, education, health, living organisms, information, and communication. This plan has been only partially offset by the alter-globalization movement, starting with the events that took place at the 1999 Seattle meeting, and on a totally different and probably far more influential scale in the medium and long term, by the astounding explosion of collaborative practices on the Internet. However, lacking political and widespread citizen support as well as sufficient resources, civil society has not so far been able to develop and disseminate alternative plans for society as a whole on a global scale, even though plenty of proposals and initiatives have been developed, some more successful than others, to build a fairer, more responsible, and more solidarity-based world in all of these areas.Above all, each country tries to impose their values and collective preferences within international institutions such like WTO or UNESCO, particularly in the Medias sector. This is an excellent opportunity to promote their soft power, for instance with the promotion of the cinema.

As far as science is concerned, "[r]esearch increasingly bows to the needs of financial markets, turning competence and knowledge into commodities, making employment flexible and informal, and establishing contracts based on goals and profits for the benefit of private interests in compliance with the competition principle. The directions that research has taken in the past two decades and the changes it has undergone have drastically removed it from its initial mission (producing competence and knowledge, maintaining independence) with no questioning of its current and future missions. Despite the progress, or perhaps even as its consequence, humankind continues to face critical problems: poverty and hunger are yet to be vanquished, nuclear arms are proliferating, environmental disasters are on the rise, social injustice is growing, and so on.

Neoliberal commercialization of the commons favors the interests of pharmaceutical companies instead of the patients', of food-processing companies instead of the farmers' and consumers'. Public research policies have done nothing but support this process of economic profitability, where research results are increasingly judged by the financial markets. The system of systematically patenting knowledge and living organisms is thus being imposed throughout the planet through the 1994 WTO agreements on intellectual property. Research in many areas is now being directed by private companies."

On the global level, "[i]nstitutions dominating a specific sector also, at every level, present the risk of reliance on technical bodies that use their own references and deliberate in an isolated environment. This process can be observed with the 'community of patents' that promotes the patenting of living organisms, as well as with authorities controlling nuclear energy. This inward-looking approach is all the more dangerous that communities of experts are, in all complex technical and legal spheres, increasingly dominated by the major economic organizations that finance research and development."

On the other hand, several innovative experiments have emerged in the sphere of science, such as: conscience clauses and citizens' panels as a tool for democratizing the production system: science shops and community-based research. Politically committed scientists are also increasingly organizing at the global level.

As far as education is concerned, the effect of commoditization can be seen in the serious tightening of education budgets, which affects the quality of general education as a public service. The Global Future Online report reminds us that ". . . at the half-way point towards 2015 (author's note: the deadline for the Millennium Goals), the gaps are daunting: 80 million children (44 million of them girls) are out of school, with marginalized groups (26 million disabled and 30 million conflict-affected children) continuing to be excluded. And while universal access is critical, it must be coupled with improved learning outcomes—in particular, children achieving the basic literacy, numeracy and life skills essential for poverty reduction."

In addition to making the current educational system available universally, there is also a call to improve the system and adapt it to the speed of changes in a complex and unpredictable world. On this point, Edgar Morin asserts that we must "[r]ethink our way of organizing knowledge. This means breaking down the traditional barriers between disciplines and designing new ways to reconnect that which has been torn apart." The UNESCO report drawn up by Morin contains "seven principles for education of the future": detecting the error and illusion that have always parasitized the human spirit and human behavior; making knowledge relevant, i.e. a way of thinking that makes distinctions and connections; teaching the human condition; teaching terrestrial identity; facing human and scientific uncertainties and teaching strategies to deal with them; teaching understanding of the self and of others, and an ethics for humankind.

The exponential growth of new technologies, the Internet in particular, has gone hand in hand with the development over the last decade of a global community producing and exchanging goods. This development is permanently altering the shape of the entertainment, publishing, and music and media industries, among others. It is also influencing the social behavior of increasing numbers of people, along with the way in which institutions, businesses, and civil society are organized. Peer-to-peer communities and collective knowledge-building projects such as Wikipedia have involved millions of users around the world. There are even more innovative initiatives, such as alternatives to private copyright such as Creative Commons, cyber democracy practices, and a real possibility of developing them on the sectoral, regional, and global levels.

Regional views

Regional players, whether regional conglomerates such as Mercosur and the European Union, or major countries seen as key regional players such as China, the United States, and India, are taking a growing interest in world governance. Examples of discussion of this issue can be found in the works of: Martina Timmermann et al., Institutionalizing Northeast Asia: Regional Steps toward Global Governance; Douglas Lewis, Global Governance and the Quest for Justice - Volume I: International and Regional Organizations; Olav Schram Stokke, "Examining the Consequences of International Regimes," which discusses Northern, or Arctic region building in the context of international relations; Jeffery Hart and Joan Edelman Spero, "Globalization and Global Governance in the 21st Century," which discusses the push of countries such as Mexico, Brazil, India, China, Taiwan, and South Korea, "important regional players" seeking "a seat at the table of global decision-making"; Dr. Frank Altemöller, “International Trade: Challenges for Regional and Global Governance: A comparison between Regional Integration Models in Eastern Europe and Africa – and the role of the WTO”, and many others.Interdependence among countries and regions hardly being refutable today, regional integration is increasingly seen not only as a process in itself, but also in its relation to the rest of the world, sometimes turning questions like "What can the world bring to my country or region?" into "What can my country or region bring to the rest of the world?" Following are a few examples of how regional players are dealing with these questions.

Africa

Often seen as a problem to be solved rather than a people or region with an opinion to express on international policy, Africans and Africa draw on a philosophical tradition of community and social solidarity that can serve as inspiration to the rest of the world and contribute to building world governance. One example is given by Sabelo J. Ndlovu-Gathseni when he reminds us of the relevance of the Ubuntu concept, which stresses the interdependence of human beings.African civil society has thus begun to draw up proposals for governance of the continent, which factor in all of the dimensions: local, African, and global. Examples include proposals by the network "Dialogues sur la gouvernance en Afrique" for "the construction of a local legitimate governance," state reform "capable of meeting the continent's development challenges," and "effective regional governance to put an end to Africa's marginalization."

United States

Foreign-policy proposals announced by President Barack Obama include restoring the Global Poverty Act, which aims to contribute to meeting the UN Millennium Development Goals to reduce by half the world population living on less than a dollar a day by 2015. Foreign aid is expected to double to 50 billion dollars. The money will be used to help build educated and healthy communities, reduce poverty and improve the population's health.In terms of international institutions, The White House Web site advocates reform of the World Bank and the IMF, without going into any detail.

Below are further points in the Obama-Biden plan for foreign policy directly related to world governance:

- strengthening of the nuclear non-proliferation treaty;

- global de-nuclearization in several stages including stepping up cooperation with Russia to significantly reduce stocks of nuclear arms in both countries;

- revision of the culture of secrecy: institution of a National Declassification Center to make declassification secure but routine, efficient, and cost-effective;

- increase in global funds for AIDS, TB and malaria. Eradication of malaria-related deaths by 2015 by making medicines and mosquito nets far more widely available;

- increase in aid for children and maternal health as well as access to reproductive health-care programs;

- creation of a 2-billion-dollar global fund for education. Increased funds for providing access to drinking water and sanitation;

- other similarly large-scale measures covering agriculture, small- and medium-sized enterprises and support for a model of international trade that fosters job creation and improves the quality of life in poor countries;

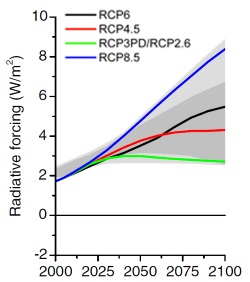

- in terms of energy and global warming, Obama advocates a) an 80% reduction of greenhouse-gas emissions by 2050 b) investing 150 billion dollars in alternative energies over the next 10 years and c) creating a Global Energy Forum capable of initiating a new generation of climate protocols.

Latin America

The 21st century has seen the arrival of a new and diverse generation of left-wing governments in Latin America. This has opened the door to initiatives to launch political and governance renewal. A number of these initiatives are significant for the way they redefine the role of the state by drawing on citizen participation, and can thus serve as a model for a future world governance built first and foremost on the voice of the people. The constituent assemblies in Ecuador and Bolivia are fundamental examples of this phenomenon.In Ecuador, social and indigenous movements were behind the discussions that began in 1990 on setting up a constituent assembly. In the wake of Rafael Correa's arrival at the head of the country in November 2006, widespread popular action with the slogan "que se vayan todos" (let them all go away) succeeded in getting all the political parties of congress to accept a convocation for a referendum on setting up the assembly.

In April 2007, Rafael Correa's government organized a consultation with the people to approve setting up a constituent assembly. Once it was approved, 130 members of the assembly were elected in September, including 100 provincial members, 24 national members and 6 for migrants in Europe, Latin America and the USA. The assembly was officially established in November. Assembly members belonged to traditional political parties as well as the new social movements. In July 2008, the assembly completed the text for the new constitution and in September 2008 there was a referendum to approve it. Approval for the new text won out, with 63.9% of votes for compared to 28.1% of votes against and a 24.3% abstention rate.

The new constitution establishes the rule of law on economic, social, cultural and environmental rights (ESCER). It transforms the legal model of the social state subject to the rule of law into a "constitution of guaranteed well-being" (Constitución del bienestar garantizado) inspired by the ancestral community ideology of "good living" propounded by the Quechuas of the past, as well as by 21st century socialist ideology. The constitution promotes the concept of food sovereignty by establishing a protectionist system that favors domestic production and trade. It also develops a model of public aid for education, health, infrastructures and other services.

In addition, it adds to the three traditional powers, a fourth power called the Council of Citizen Participation and Social Control, made up of former constitutional control bodies and social movements, and mandated to assess whether public policies are constitutional or not.

The new Bolivian constitution was approved on 25 January 2009 by referendum, with 61.4% votes in favor, 38.6% against and a 90.2% turnout. The proposed constitution was prepared by a constituent assembly that did not only reflect the interests of political parties and the elite, but also represented the indigenous peoples and social movements. As in Ecuador, the proclamation of a constituent assembly was demanded by the people, starting in 1990 at a gathering of indigenous peoples from the entire country, continuing with the indigenous marches in the early 2000s and then with the Program Unity Pact (Pacto de Unidad Programático) established by family farmers and indigenous people in September 2004 in Santa Cruz.

The constitution recognizes the autonomy of indigenous peoples, the existence of a specific indigenous legal system, exclusive ownership of forest resources by each community and a quota of indigenous members of parliament. It grants autonomy to counties, which have the right to manage their natural resources and elect their representatives directly. The latifundio system has been outlawed, with maximum ownership of 5,000 hectares allowed per person. Access to water and sanitation are covered by the constitution as human rights that the state has to guarantee, as well as other basic services such as electricity, gas, postal services, and telecommunications that can be provided by either the state or contracting companies. The new constitution also establishes a social and community economic model made up of public, private, and social organizations, and cooperatives. It guarantees private initiative and freedom of enterprise, and assigns public organizations the task of managing natural resources and related processes as well as developing public services covered by the constitution. National and cooperative investment is favored over private and international investment. The "unitary plurinational" state of Bolivia has 36 official indigenous languages along with Spanish. Natural resources belong to the people and are administered by the state. The form of democracy in place is no longer considered as exclusively representative and/or based on parties. Thus, "the people deliberate and exercise government via their representatives and the constituent assembly, the citizen legislative initiative and the referendum..." and "popular representation is exercised via the political parties, citizen groups, and indigenous peoples." This way, "political parties, and/or citizen groups and/or indigenous peoples can present candidates directly for the offices of president, vice-president, senator, house representative, constituent-assembly member, councilor, mayor, and municipal agent. The same conditions apply legally to all..."

Also in Latin America: "Amazonia . . . is an enormous biodiversity reservoir and a major climate-regulation agent for the planet but is being ravaged and deteriorated at an accelerated pace; it is a territory almost entirely devoid of governance, but also a breeding place of grassroots organization initiatives.". "Amazonia can be the fertile field of a true school of 'good' governance if it is looked after as a common and valuable good, first by Brazilians (65% of Amazonia is within Brazilian borders) and the people of the South American countries surrounding it, but also by all the Earth's inhabitants." Accordingly, "[f]rom a world-governance perspective, [Amazonia] is in a way an enormous laboratory. Among other things, Amazonia enables a detailed examination of the negative effects of productivism and of the different forms of environmental packaging it can hide behind, including 'sustainable development.' Galloping urbanization, Human Rights violations, the many different types of conflicts (14 different types of conflicts have been identified within the hundreds of cases observed in Amazonia), protection of indigenous populations and their active participation in local governance: these are among the many Amazonian challenges also affecting the planet as a whole, not to mention the environment. The hosts of local initiatives, including among the indigenous populations, are however what may be most interesting in Amazonia in that they testify to the real, concrete possibility of a different form of organization that combines a healthy local economy, good social cohesion, and a true model of sustainable development—this time not disguised as something else. All of this makes Amazonia 'a territory of solutions.'"

According to Arnaud Blin, the Amazonian problem helps to define certain fundamental questions on the future of humankind. First, there is the question of social justice: "[H]ow do we build a new model of civilization that promotes social justice? How do we set up a new social architecture that allows us to live together?" The author goes on to refer to concepts such as the concept of "people's territory " or even "life territory" rooted in the indigenous tradition and serving to challenge private property and social injustice. He then suggests that the emerging concept of the "responsibility to protect," following up on the "right of humanitarian intervention" and until now used to try to protect populations endangered by civil wars, could also be applied to populations threatened by economic predation and to environmental protection.

Asia

The growing interest in world governance in Asia represents an alternative approach to official messages, dominated by states' nationalist visions. An initiative to develop proposals for world governance took place in Shanghai in 2006, attended by young people from every continent. The initiative produced ideas and projects that can be classified as two types: the first and more traditional type, covering the creation of a number of new institutions such as an International Emissions Organization, and a second more innovative type based on organizing network-based systems. For example, a system of cooperative control on a worldwide level among states and self-organization of civil society into networks using new technologies, a process that should serve to set up a Global Calling-for-Help Center or a new model based on citizens who communicate freely, share information, hold discussions, and seek consensus-based solutions. They would use the Internet and the media, working within several types of organizations: universities, NGOs, local volunteers and civil-society groups.Given the demographic importance of the continent, the development of discussion on governance and practices in Asia at the regional level, as well as global-level proposals, will be decisive in the years ahead in the strengthening of global dialog among all sorts of stakeholders, a dialog that should produce a fairer world order.

Europe

According to Michel Rocard, Europe does not have a shared vision, but a collective history that allows Europeans to opt for projects for gradual political construction such as the European Union. Drawing on this observation, Rocard conceives of a European perspective that supports the development of three strategies for constructing world governance: reforming the UN, drawing up international treaties to serve as the main source of global regulations, and "the progressive penetration of the international scene by justice."Rocard considers that there are a number of "great questions of the present days" including recognition by all nations of the International Criminal Court, the option of an international police force authorized to arrest international criminals, and the institution of judicial procedures to deal with tax havens, massively polluting activities, and states supporting terrorist activities. He also outlines "new problems" that should foster debate in the years to come on questions such as a project for a Declaration of Interdependence, how to re-equilibrate world trade and WTO activities, and how to create world regulations for managing collective goods (air, drinking water, oil, etc.) and services (education, health, etc.).

Martin Ortega similarly suggests that the European Union should make a more substantial contribution to global governance, particularly through concerted action in international bodies. European states, for instance, should reach an agreement on the reform of the United Nations Security Council.

In 2011, the European Strategy and Policy Analysis System (ESPAS), an inter-institutional pilot project of the European Union which aims to assist EU policy formulation through the identification and critical analysis of long-term global trends, highlighted the importance of expanding global governance over the next 20 years.

Stakeholders' views

It is too soon to give a general account of the view of world-governance stakeholders, although interest in world governance is on the rise on the regional level, and we will certainly see different types of stakeholders and social sectors working to varying degrees at the international level and taking a stand on the issue in the years to come.Institutional and state stakeholders

Members of parliament

The World Parliamentary Forum, open to members of parliament from all nations and held every year at the same time as the World Social Forum, drew up a declaration at the sixth forum in Caracas in 2006. The declaration contains a series of proposals that express participants' opinion on the changes referred to.Regional organizations

The European Commission referred to global governance in its White Paper on European Governance. It contends that the search for better global governance draws on the same set of shared challenges humanity is currently facing. These challenges can be summed up by a series of goals: sustainable development, security, peace and equity (in the sense of "fairness").Non-state stakeholders

The freedom of thought enjoyed by non-state stakeholders enables them to formulate truly alternative ideas on world-governance issues, but they have taken little or no advantage of this opportunity.Pierre Calame believes that "[n]on-state actors have always played an essential role in global regulation, but their role will grow considerably in this, the beginning of the twenty-first Century . . . Non-state actors play a key role in world governance in different domains . . . To better understand and develop the non-state actors' role, it should be studied in conjunction with the general principles of governance." "Non-state actors, due to their vocation, size, flexibility, methods of organization and action, interact with states in an equal manner; however this does not mean that their action is better adapted."

One alternative idea encapsulated by many not-for-profit organisations relates to ideas in the 'Human Potential Movement' and might be summarised as a mission statement along these lines: 'To create an accepted framework for all humankind, that is self-regulating and which enables every person to achieve their fullest potential in harmony with the world and its place in existence.'

Since the Rio Earth Summit in 1992, references to the universal collective of humanity have begun using the term 'humankind' rather than 'mankind', given the gender neutral quality of the former.

'Self-regulation' is meant to invoke the concept of regulation which includes rule-making such as laws, and related ideas e.g. legal doctrine as well as other frameworks. However its scope is wider than this and intended to encompass cybernetics which allows for the study of regulation in as many varied contexts as possible from the regulation of gene expression to the Press Complaints Commission for example.

World Religious Leaders

Since 2005, religious leaders from a diverse array of faith traditions have engaged in dialogue with G8 leaders around issues of global governance and world risk. Drawing on the cultural capital of diverse religious traditions, they seek to strengthen democratic norms by influencing political leaders to include the interests of the most vulnerable when they make their decisions. Some have argued that religion is a key to transforming or fixing global governance.Proposals

Several stakeholders have produced lists of proposals for a new world governance that is fairer, more responsible, solidarity-based, interconnected and respectful of the planet's diversity. Some examples are given below.Joseph E. Stiglitz proposes a list of reforms related to the internal organization of international institutions and their external role in the framework of global-governance architecture. He also deals with global taxation, the management of global resources and the environment, the production and protection of global knowledge, and the need for a global legal infrastructure.

A number of other proposals are contained in the World Governance Proposal Paper: giving concrete expression to the principle of responsibility; granting civil society greater involvement in drawing up and implementing international regulations; granting national parliaments greater involvement in drawing up and implementing international regulations; re-equilibrating trade mechanisms and adopting regulations to benefit the southern hemisphere; speeding up the institution of regional bodies; extending and specifying the concept of the commons; redefining proposal and decision-making powers in order to reform the United Nations; developing independent observation, early-warning, and assessment systems; diversifying and stabilizing the basis for financing international collective action; and engaging in a wide-reaching process of consultation, a new Bretton Woods for the United Nations.

This list provides more examples of proposals:

- the security of societies and its correlation with the need for global reforms——a controlled legally-based economy focused on stability, growth, full employment, and North-South convergence;

- equal rights for all, implying the institution of a global redistribution process;

- eradication of poverty in all countries;

- sustainable development on a global scale as an absolute imperative in political action at all levels;

- fight against the roots of terrorism and crime;

- consistent, effective, and fully democratic international institutions;

- Europe sharing its experience in meeting the challenges of globalization and adopting genuine partnership strategies to build a new form of multilateralism.

- Democratic policy at the global level requires legitimacy of popular control through representative and direct mechanisms;

- Citizen participation in decision making at global levels requires equality of opportunity to all citizens of the world;

- Multiple spheres of governance, from local to provincial to national to regional and global, should mutually support democratization of decision making at all levels;

- Global democracy must guarantee that global public goods are equitably accessible to all citizens of the world;

- Blockchain and decentralized platforms can be considered as hyper-political and Global governance tools, capable to manage social interactions on large scale and dismiss traditional central authorities.

Academic tool or discipline

In the light of the unclear meaning of the term "global governance" as a concept in international politics, some authors have proposed defining it not in substantive, but in disciplinary and methodological terms. For these authors, global governance is better understood as an analytical concept or optic that provides a specific perspective on world politics different from that of conventional international relations theory. Thomas G. Weiss and Rorden Wilkinson have even argued that global governance has the capacity to overcome some of the fragmentation of international relations as a discipline particularly when understood as a set of questions about the governance of world orders.Some universities, including those offering courses in international relations, have begun to establish degree programmes in global governance.

Context

There are those who believe that world architecture depends on establishing a system of world governance. However, the equation is currently becoming far more complicated: Whereas the process used to be about regulating and limiting the individual power of states to avoid disturbing or overturning the status quo, the issue for today's world governance is to have a collective influence on the world's destiny by establishing a system for regulating the many interactions that lie beyond the province of state action. The political homogenization of the planet that has followed the advent of what is known as liberal democracy in its many forms should make it easier to establish a world governance system that goes beyond market laissez-faire and the democratic peace originally formulated by Immanuel Kant, which constitutes a sort of geopolitical laissez-faire.Another view regarding the establishment of global governance is based on the difficulties to achieve equitable development at the world scale. "To secure for all human beings in all parts of the world the conditions allowing a decent and meaningful life requires enormous human energies and far-reaching changes in policies. The task is all the more demanding as the world faces numerous other problems, each related to or even part of the development challenge, each similarly pressing, and each calling for the same urgent attention. But, as Arnold Toynbee has said, 'Our age is the first generation since the dawn of history in which mankind dares to believe it practical to make the benefits of civilization available to the whole human race'."

Need

Because of the heterogeneity of preferences, which are enduring despite globalization, are often perceived as an implacable homogenization process. Americans and Europeans provide a good example of this point: on some issues they have differing common grounds in which the division between the public and private spheres still exist. Tolerance for inequalities and the growing demand for redistribution, attitudes toward risk, and over property rights vs human rights, set the stage. In certain cases, globalization even serves to accentuate differences rather than as a force for homogenization. Responsibility must play its part with respect to regional and International governments, when balancing the needs of its citizenry.With the growing emergence of a global civic awareness, comes opposition to globalization and its effects. A rapidly growing number of movements and organizations have taken the debate to the international level. Although it may have limitations, this trend is one response to the increasing importance of world issues, that effect the planet.

Crisis of purpose

Pierre Jacquet, Jean Pisani-Ferry, and Laurence Tubiana argue that "[t]o ensure that decisions taken for international integration are sustainable, it is important that populations see the benefits, that states agree on their goals and that the institutions governing the process are seen as legitimate. These three conditions are only partially being met."The authors refer to a "crisis of purpose" and international institutions suffering from "imbalance" and inadequacy. They believe that for these institutions, "a gap has been created between the nature of the problems that need tackling and an institutional architecture which does not reflect the hierarchy of today's problems. For example, the environment has become a subject of major concern and central negotiation, but it does not have the institutional support that is compatible with its importance."

World government

Global governance is not world government, and even less democratic globalization. In fact, global governance would not be necessary, were there a world government. Domestic governments have monopolies on the use of force—the power of enforcement. Global governance refers to the political interaction that is required to solve problems that affect more than one state or region when there is no power to enforce compliance. Problems arise, and networks of actors are constructed to deal with them in the absence of an international analogue to a domestic government. This system has been termed disaggregated sovereignty.Consensus example

Improved global problem solving need not involve the establishment of additional powerful formal global institutions. It does involve building consensus on norms and practices. One such area, currently under construction, is the development and improvement of accountability mechanisms. For example, the UN Global Compact brings together companies, UN agencies, labor organizations, and civil society to support universal environmental and social principles. Participation is entirely voluntary, and there is no enforcement of the principles by an outside regulatory body. Companies adhere to these practices both because they make economic sense, and because stakeholders, especially shareholders, can monitor their compliance easily. Mechanisms such as the Global Compact can improve the ability of affected individuals and populations to hold companies accountable. However, corporations participating in the UN Global Compact have been criticized for their merely minimal standards, the absence of sanction-and-control measures, their lack of commitment to social and ecological standards, minimal acceptance among corporations around the world, and the high cost involved in reporting annually to small and medium-sized businessBitcoin & Beyond: Blockchains, Globalization, and Global Governance workshop brings together an interdisciplinary group of researchers to examine the implications that blockchains pose for globalization and global governance.

Issues

Expansion of normative mechanisms and globalization of institutions

One effect of globalization is the increasing regulation of businesses in the global marketplace. Jan Aart Scholte asserts, however, that these changes are inadequate to meet the needs: "Along with the general intensified globalization of social relations in contemporary history has come an unprecedented expansion of regulatory apparatuses that cover planetary jurisdictions and constituencies. On the whole, however, this global governance remains weak relative to pressing current needs for global public policy. Shortfalls in moral standing, legal foundations, material delivery, democratic credentials and charismatic leadership have together generated large legitimacy deficits in existing global regimes."Proposals and initiatives have been developed by various sources to set up networks and institutions operating on a global scale: political parties, unions, regional authorities, and members of parliament in sovereign states.

Formulation and objectives

One of the conditions for building a world democratic governance should be the development of platforms for citizen dialogue on the legal formulation of world governance and the harmonization of objectives.This legal formulation could take the form of a Global Constitution. According to Pierre Calame and Gustavo Marin, "[a] Global Constitution resulting from a process for the institution of a global community will act as the common reference for establishing the order of rights and duties applicable to United Nations agencies and to the other multilateral institutions, such as the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the World Trade Organization." As for formulating objectives, the necessary but insufficient ambition of the United Nations Millennium Development Goals, which aim to safeguard humankind and the planet, and the huge difficulties in implementing them, illustrates the inadequacy of institutional initiatives that do not have popular support for having failed to invite citizens to take part in the elaboration process.

Furthermore, the Global Constitution "must clearly express a limited number of overall objectives that are to be the basis of global governance and are to guide the common action of the U.N. agencies and the multilateral institutions, where the specific role of each of these is subordinated to the pursuit of these common objectives."

Calame proposes the following objectives:

- instituting the conditions for sustainable development;

- reducing inequalities;

- establishing lasting peace while respecting diversity.

Reforming international institutions

Is the UN capable of taking on the heavy responsibility of managing the planet's serious problems? More specifically, can the UN reform itself in such a way as to be able to meet this challenge? At a time when the financial crisis of 2008 is raising the same questions posed by the climate disasters of previous years regarding the unpredictable consequences of disastrous human management, can international financial institutions be reformed in such a way as to go back to their original task, which was to provide financial help to countries in need?Lack of political will and citizen involvement at the international level has also brought about the submission of international institutions to the "neoliberal" agenda, particularly financial institutions such as the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Trade Organization (WTO). Pierre Calame gives an account of this development, while Joseph E. Stiglitz points out that the need for international institutions like the IMF, the World Bank, and the WTO has never been so great, but people's trust in them has never been so low.

One of the key aspects of the United Nations reform is the problem of the representativeness of the General Assembly. The Assembly operates on the principle of "one state, one vote," so that states of hugely varying sizes have the same effect on the vote, which distorts representativeness and results in a major loss of credibility. Accordingly, "the General Assembly has lost any real capacity to influence. This means that the mechanisms for action and consultation organized by rich countries have the leading role."

Gustave Massiah advocates defining and implementing a radical reform of the UN. The author proposes building new foundations that can provide the basis for global democracy and the creation of a Global Social Contract, rooted in the respect and protection of civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights, as well as in the recognition of the strategic role of international law.

The three ‘gaps’ in global governance

There is the jurisdictional gap, between the increasing need for global governance in many areas - such as health - and the lack of an authority with the power, or jurisdiction, to take action. Moreover, the gap of incentive between the need for international cooperation and the motivation to undertake it. The incentive gap is said to be closing as globalization provides increasing impetus for countries to cooperate. However, there are concerns that, as Africa lags further behind economically, its influence on global governance processes will diminish. At last, the participation gap, which refers to the fact that international cooperation remains primarily the affair of governments, leaving civil society groups on the fringes of policy-making. On the other hand, globalization of communication is facilitating the development of global civil society movements.Global governance failure

Inadequate global institutions, agreements or networks as well as political and national interests may impede global governance and lead to failures. Such are the consequence of ineffective global governance processes. Qin calls it a necessity to "reconstruct ideas for effective global governance and sustainable world order, which should include the principles of pluralism, partnership, and participation" for a change to this phenomenon. The 2012 Global Risks Report places global governance failure at the center of gravity in its geopolitical category.Studies of global governance

Studies of global governance are conducted at several academic institutions such as the LSE Department of International Relations (with a previous institution LSE Global Governance closed as a formal research centre of the LSE on 31 July 2011), the Leuven Centre for Global Governance Studies, the Global Governance Programme at the European University Institute, and the Center for Global Governance at Columbia Law School.Journals dedicated to the studies of global governance include the Chinese Journal of Global Governance, the Global Policy Journal at Durham University, Global Governance: A Review of Multilateralism and International Organizations, and Kosmos Journal for Global Transformation.