https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abrahamic_religions

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions centered around the worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned throughout the Abrahamic religious scriptures of the Quran, Hebrew, and Christian Bible.

Jewish tradition claims that the Twelve Tribes of Israel are descended from Abraham through his son Isaac and grandson Jacob, whose sons formed the nation of the Israelites in Canaan (or the Land of Israel); Islamic tradition claims that twelve Arab tribes known as the Ishmaelites are descended from Abraham through his son Ishmael in the Arabian Peninsula.

In its early stages, the Israelite religion was derived from the Canaanite religions of the Bronze Age; by the Iron Age, it had become distinct from other Canaanite religions as it shed polytheism for monolatry. The monolatrist nature of Yahwism was further developed in the period following the Babylonian captivity, eventually emerging as a firm religious movement of monotheism. In the 1st century CE, Christianity emerged as a splinter movement out of Judaism in the Land of Israel, developed under the Apostles of Jesus of Nazareth; it spread widely after it was adopted by the Roman Empire as a state religion in the 4th century CE. In the 7th century CE, Islam was founded by Muhammad in the Arabian Peninsula; it spread widely through the early Muslim conquests, shortly after his death.

Alongside the Indian religions, the Iranian religions, and the East Asian religions, the Abrahamic religions make up the largest major division in comparative religion. By total number of adherents, Christianity and Islam comprise the largest and second-largest religious movements in the world, respectively. Abrahamic religions with fewer adherents include Judaism, the Baháʼí Faith, Druzism, Samaritanism, and Rastafari.

Etymology

The Catholic scholar of Islam Louis Massignon stated that the phrase "Abrahamic religion" means that all these religions come from one spiritual source. The modern term comes from the plural form of a Quranic reference to dīn Ibrāhīm, 'religion of Ibrahim', Arabic form of Abraham's name.

God's promise at Genesis 15:4–8 regarding Abraham's heirs became paradigmatic for Jews, who speak of him as "our father Abraham" (Avraham Avinu). With the emergence of Christianity, Paul the Apostle, in Romans 4:11–12, likewise referred to him as "father of all" those who have faith, circumcised or uncircumcised. Islam likewise conceived itself as the religion of Abraham. All the major Abrahamic religions claim a direct lineage to Abraham:

- Abraham is recorded in the Torah as the ancestor of the Israelites through his son Isaac, born to Sarah through a promise made in Genesis.

- Christians affirm the ancestral origin of the Jews in Abraham. Christianity also claims that Jesus was descended from Abraham.

- Muhammad, as an Arab, is believed by Muslims to be descended from Abraham's son Ishmael, through Hagar. Jewish tradition also equates the descendants of Ishmael, Ishmaelites, with Arabs, while the descendants of Isaac by Jacob, who was also later known as Israel, are the Israelites.

- The Bahá'í Faith states in its scripture that Bahá'ullah descended from Abraham through his wife Keturah's sons.

Debates regarding the term

The appropriateness of grouping Judaism, Christianity, and Islam by the terms "Abrahamic religions" or "Abrahamic traditions" has, at times, been challenged. The common Christian beliefs of Incarnation, Trinity, and the resurrection of Jesus, for example, are not accepted by Judaism or Islam (see for example Islamic view of Jesus' death). There are key beliefs in both Islam and Judaism that are not shared by most of Christianity (such as abstinence from pork), and key beliefs of Islam, Christianity, and the Baháʼí Faith not shared by Judaism (such as the prophetic and Messianic position of Jesus, respectively).

Adam Dodds argues that the term "Abrahamic faiths", while helpful, can be misleading, as it conveys an unspecified historical and theological commonality that is problematic on closer examination. While there is a commonality among the religions, in large measure their shared ancestry is peripheral to their respective foundational beliefs and thus conceals crucial differences. Alan L. Berger, professor of Judaic Studies at Florida Atlantic University, wrote that although "Judaism birthed both Christianity and Islam," the three faiths "understand the role of Abraham" in different ways. Aaron W. Hughes, meanwhile, describes the term as "imprecise" and "largely a theological neologism".

An alternative designation for the "Abrahamic religions", "desert monotheism", may also have unsatisfactory connotations.

Religions

Judaism

One of Judaism's primary texts is the Tanakh, an account of the Israelites' relationship with God from their earliest history until the building of the Second Temple (c. 535 BCE). Abraham is hailed as the first Hebrew and the father of the Jewish people. One of his great-grandsons was Judah, from whom the religion ultimately gets its name. The Israelites were initially a number of tribes who lived in the Kingdom of Israel and Kingdom of Judah.

After being conquered and exiled, some members of the Kingdom of Judah eventually returned to Israel. They later formed an independent state under the Hasmonean dynasty in the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, before becoming a client kingdom of the Roman Empire, which also conquered the state and dispersed its inhabitants. From the 2nd to the 6th centuries, Rabbinical Jews (believed to be descended from the historical Pharisees) wrote the Talmud, a lengthy work of legal rulings and Biblical exegesis which, along with the Tanakh, is a key text of Rabbinical Judaism. Karaite Jews (believed to be descended from the Sadducees) and the Beta Israel reject the Talmud and the idea of an Oral Torah, following the Tanakh only.

Christianity

Christianity began in the 1st century as a sect within Judaism initially led by Jesus. His followers viewed him as the Messiah, as in the Confession of Peter; after his crucifixion and death they came to view him as God incarnate, who was resurrected and will return at the end of time to judge the living and the dead and create an eternal Kingdom of God. Within a few decades the new movement split from Judaism. Christian teaching is based on the Old and New Testaments of the Bible.

After several periods of alternating persecution and relative peace vis a vis the Roman authorities under different administrations, Christianity became the state church of the Roman Empire in 380, but has been split into various churches from its beginning. An attempt was made by the Byzantine Empire to unify Christendom, but this formally failed with the East–West Schism of 1054. In the 16th century, the birth and growth of Protestantism during the Reformation further split Christianity into many denominations. The largest post-Reformation branching is the Latter Day Saint movement.

Islam

Islam is based on the teachings of the Quran. Although it considers Muhammad to be the Seal of the prophets, Islam teaches that every prophet preached Islam, as the word Islam literally means submission to God, the main concept preached by all Abrahamic prophets. Although the Quran is the central religious text of Islam, which Muslims believe to be a revelation from God, other Islamic books considered to be revealed by God before the Quran, mentioned by name in the Quran are the Tawrat (Torah) revealed to the prophets and messengers amongst the Children of Israel, the Zabur (Psalms) revealed to Dawud (David) and the Injil (the Gospel) revealed to Isa (Jesus). The Quran also mentions God having revealed the Scrolls of Abraham and the Scrolls of Moses.

The teachings of the Quran are believed by Muslims to be the direct and final revelation and words of God. Islam, like Christianity, is a universal religion (i.e. membership is open to anyone). Like Judaism, it has a strictly unitary conception of God, called tawhid, or "strict" monotheism.

Other Abrahamic religions

Historically, the Abrahamic religions have been considered to be Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Some of this is due to the age and larger size of these three. The other, similar religions were seen as either too new to judge as being truly in the same class, or too small to be of significance to the category.

However, some of the restrictions of Abrahamic to these three is due only to tradition in historical classification. Therefore, restricting the category to these three religions has come under criticism. The religions listed below here claim Abrahamic classification, either by the religions themselves, or by scholars who study them.

Baháʼí Faith

The Baháʼí Faith, which developed from Shi'a Islam during the late 19th century, is a world religion that has been listed as Abrahamic by scholarly sources in various fields. Monotheistic, it recognizes Abraham as one of a number of Manifestations of God including Adam, Moses, Zoroaster, Krishna, Gautama Buddha, Jesus, Muhammad, the Báb, and ultimately Baháʼu'lláh. God communicates his will and purpose to humanity through these intermediaries, in a process known as progressive revelation.

Druzism

The Druze Faith or Druzism is a monotheistic religion based on the teachings of high Islamic figures like Hamza ibn-'Ali ibn-Ahmad and Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, and Greek philosophers such as Plato and Aristotle.

The Epistles of Wisdom is the foundational text of the Druze faith. The Druze faith incorporates elements of Islam's Ismailism, Gnosticism, Neoplatonism, Pythagoreanism, Christianity, Hinduism and other philosophies and beliefs, creating a distinct and secretive theology known to interpret esoterically religious scriptures, and to highlight the role of the mind and truthfulness. The Druze follow theophany, and believe in reincarnation or the transmigration of the soul. At the end of the cycle of rebirth, which is achieved through successive reincarnations, the soul is united with the Cosmic Mind (Al Aaqal Al Kulli). In the Druze faith, Jesus is considered one of God's important prophets.

Rastafari

The heterogeneous Rastafari movement, sometimes termed Rastafarianism, which originated in Jamaica is classified by some scholars as an international socio-religious movement, and by others as a separate Abrahamic religion. Classified as both a new religious movement and social movement, it developed in Jamaica during the 1930s. It lacks any centralised authority and there is much heterogeneity among practitioners, who are known as Rastafari, Rastafarians, or Rastas.

Rastafari refer to their beliefs, which are based on a specific interpretation of the Bible, as "Rastalogy". Central is a monotheistic belief in a single God—referred to as Jah—who partially resides within each individual. The former Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie, is given central importance; many Rastas regard him as the returned Messiah, the incarnation of Jah on Earth, and as the Second Coming of Christ. Others regard him as a human prophet who fully recognised the inner divinity within every individual. Rastafari is Afrocentric and focuses its attention on the African diaspora, which it believes is oppressed within Western society, or "Babylon" Many Rastas call for the resettlement of the African diaspora in either Ethiopia or Africa more widely, referring to this continent as the Promised Land of "Zion". Other interpretations shift focus on to the adoption of an Afrocentric attitude while living outside of Africa. Rastas refer to their practices as "livity". Communal meetings are known as "groundations", and are typified by music, chanting, discussions, and the smoking of cannabis, the latter being regarded as a sacrament with beneficial properties. Rastas place emphasis on what they regard as living 'naturally', adhering to ital dietary requirements, allowing their hair to form into dreadlocks, and following patriarchal gender roles.

Samaritanism

The Samaritans adhere to the Samaritan Torah, which they believe is the original, unchanged Torah, as opposed to the Torah used by Jews. In addition to the Samaritan Torah, Samaritans also revere their version of the Book of Joshua and recognize some later Biblical figures such as Eli.

Samaritanism is internally described as the religion that began with Moses, unchanged over the millennia that have since passed. Samaritans believe Judaism and the Jewish Torah have been corrupted by time and no longer serve the duties God mandated on Mount Sinai. While Jews view the Temple Mount in Jerusalem as the most sacred location in their faith, Samaritans regard Mount Gerizim, near Nablus, as the holiest spot on Earth.

Other Samaritan religious works include the Memar Markah, the Samaritan liturgy, and Samaritan law codes and biblical commentaries; scholars have various theories concerning the actual relationships between these three texts. The Samaritan Pentateuch first became known to the Western world in 1631, proving the first example of the Samaritan alphabet and sparking an intense theological debate regarding its relative age versus the Masoretic Text.

Mandaeism

Mandaeism (Classical Mandaic: ࡌࡀࡍࡃࡀࡉࡉࡀ mandaiia; Arabic: المندائيّة al-Mandāʾiyya), sometimes also known as Nasoraeanism or Sabianism, is a Gnostic, monotheistic and ethnic religion. Its adherents, the Mandaeans, revere Adam, Abel, Seth, Enos, Noah, Shem, Aram, and especially John the Baptist. Mandaeans consider Adam, Seth, Noah, Shem and John the Baptist prophets, with Adam being the founder of the religion and John being the greatest and final prophet.

The Mandaeans speak an Eastern Aramaic language known as Mandaic. The name 'Mandaean' comes from the Aramaic manda, meaning knowledge. Within the Middle East, but outside their community, the Mandaeans are more commonly known as the صُبَّة Ṣubba (singular: Ṣubbī), or as Sabians (الصابئة, al-Ṣābiʾa). The term Ṣubba is derived from an Aramaic root related to baptism. The term Sabians derives from the mysterious religious group mentioned three times in the Quran. The name of this unidentified group, which is implied in the Quran to belong to the 'People of the Book' (ahl al-kitāb), was historically claimed by the Mandaeans as well as by several other religious groups in order to gain legal protection (dhimma) as offered by Islamic law. Occasionally, Mandaeans are also called "Christians of Saint John".

Origins and history

The civilizations that developed in Mesopotamia influenced some religious texts, particularly the Hebrew Bible and the Book of Genesis. Abraham is said to have originated in Mesopotamia.

Judaism regards itself as the religion of the descendants of Jacob, a grandson of Abraham. It has a strictly unitary view of God, and the central holy book for almost all branches is the Masoretic Text as elucidated in the Oral Torah. In the 19th century and 20th centuries Judaism developed a small number of branches, of which the most significant are Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform.

Christianity began as a sect of Judaism in the Mediterranean Basin of the first century CE and evolved into a separate religion—Christianity—with distinctive beliefs and practices. Jesus is the central figure of Christianity, considered by almost all denominations to be God the Son, one person of the Trinity. (See God in Christianity.) The Christian biblical canons are usually held to be the ultimate authority, alongside sacred tradition in some denominations (such as the Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church). Over many centuries, Christianity divided into three main branches (Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant), dozens of significant denominations, and hundreds of smaller ones.

Islam arose in the Arabian Peninsula in the 7th century CE with a strictly unitary view of God. Muslims hold the Quran to be the ultimate authority, as revealed and elucidated through the teachings and practices of a central, but not divine, prophet, Muhammad. The Islamic faith considers all prophets and messengers from Adam through the final messenger (Muhammad) to carry the same Islamic monotheistic principles. Soon after its founding, Islam split into two main branches (Sunni and Shia Islam), each of which now has a number of denominations.

The Baháʼí Faith began within the context of Shia Islam in 19th-century Persia, after a merchant named Siyyid 'Alí Muḥammad Shírází claimed divine revelation and took on the title of the Báb, or "the Gate". The Bab's ministry proclaimed the imminent advent of "He whom God shall make manifest", who Baháʼís accept as Bahá'u'lláh. Baháʼís revere the Torah, Gospels and the Quran, and the writings of the Báb, Bahá'u'lláh, and 'Abdu'l-Bahá' are considered the central texts of the faith. A vast majority of adherents are unified under a single denomination.

Common aspects

All Abrahamic religions accept the tradition that God revealed himself to the patriarch Abraham. All of them are monotheistic, and all of them conceive God to be a transcendent creator and the source of moral law. Their religious texts feature many of the same figures, histories, and places, although they often present them with different roles, perspectives, and meanings. Believers who agree on these similarities and the common Abrahamic origin tend to also be more positive towards other Abrahamic groups.

In the three main Abrahamic religions (Judaism, Christianity and Islam), the individual, God, and the universe are highly separate from each other. The Abrahamic religions believe in a judging, paternal, fully external god to which the individual and nature are both subordinate. One seeks salvation or transcendence not by contemplating the natural world or via philosophical speculation, but by seeking to please God (such as obedience with God's wishes or his law) and see divine revelation as outside of self, nature, and custom.

Monotheism

All Abrahamic religions claim to be monotheistic, worshiping an exclusive God, although one who is known by different names. Each of these religions preaches that God creates, is one, rules, reveals, loves, judges, punishes, and forgives. However, although Christianity does not profess to believe in three gods—but rather in three persons, or hypostases, united in one essence—the Trinitarian doctrine, a fundamental of faith for the vast majority of Christian denominations, conflicts with Jewish and Muslim concepts of monotheism. Since the conception of a divine Trinity is not amenable to tawhid, the Islamic doctrine of monotheism, Islam regards Christianity as variously polytheistic.

Christianity and Islam both revere Jesus (Arabic: Isa or Yasu among Muslims and Arab Christians respectively) but with vastly differing conceptions:

- Christians view Jesus as the saviour and regard him as God incarnate.

- Muslims see Isa as a Prophet of Islam and Messiah.

However, the worship of Jesus, or the ascribing of partners to God (known as shirk in Islam and as shituf in Judaism), is typically viewed as the heresy of idolatry by Islam and Judaism.

Theological continuity

All the Abrahamic religions affirm one eternal God who created the universe, who rules history, who sends prophetic and angelic messengers and who reveals the divine will through inspired revelation. They also affirm that obedience to this creator deity is to be lived out historically and that one day God will unilaterally intervene in human history at the Last Judgment. Christianity, Islam, and Judaism have a teleological view on history, unlike the static or cyclic view on it found in other cultures (the latter being common in Indian religions).

Scriptures

All Abrahamic religions believe that God guides humanity through revelation to prophets, and each religion believes that God revealed teachings to prophets, including those prophets whose lives are documented in its own scripture.

Ethical orientation

An ethical orientation: all these religions speak of a choice between good and evil, which is associated with obedience or disobedience to a single God and to Divine Law.

Eschatological world view

An eschatological world view of history and destiny, beginning with the creation of the world and the concept that God works through history, and ending with a resurrection of the dead and final judgment and world to come.

Importance of Jerusalem

Jerusalem is considered Judaism's holiest city. Its origins can be dated to 1004 BCE, when according to Biblical tradition David established it as the capital of the United Kingdom of Israel, and his son Solomon built the First Temple on Mount Moriah. Since the Hebrew Bible relates that Isaac's sacrifice took place there, Mount Moriah's importance for Jews predates even these prominent events. Jews thrice daily pray in its direction, including in their prayers pleas for the restoration and the rebuilding of the Holy Temple (the Third Temple) on mount Moriah, close the Passover service with the wistful statement "Next year in built Jerusalem," and recall the city in the blessing at the end of each meal. Jerusalem has served as the only capital for the five Jewish states that have existed in Israel since 1400 BCE (the United Kingdom of Israel, the Kingdom of Judah, Yehud Medinata, the Hasmonean Kingdom, and modern Israel). It has been majority Jewish since about 1852 and continues through today.

Jerusalem was an early center of Christianity. There has been a continuous Christian presence there since. William R. Kenan, Jr., professor of the history of Christianity at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville, writes that from the middle of the 4th century to the Islamic conquest in the middle of the 7th century, the Roman province of Palestine was a Christian nation with Jerusalem its principal city. According to the New Testament, Jerusalem was the city Jesus was brought to as a child to be presented at the temple and for the feast of the Passover. He preached and healed in Jerusalem, unceremoniously drove the money changers in disarray from the temple there, held the Last Supper in an "upper room" (traditionally the Cenacle) there the night before he was crucified on the cross and was arrested in Gethsemane. The six parts to Jesus' trial—three stages in a religious court and three stages before a Roman court—were all held in Jerusalem. His crucifixion at Golgotha, his burial nearby (traditionally the Church of the Holy Sepulchre), and his resurrection and ascension and prophecy to return all are said to have occurred or will occur there.

Jerusalem became holy to Muslims, third after Mecca and Medina. The Al-Aqsa Mosque, which translates to "farthest mosque" in sura Al-Isra in the Quran and its surroundings are addressed in the Quran as "the holy land". Muslim tradition as recorded in the ahadith identifies al-Aqsa with a mosque in Jerusalem. The first Muslims did not pray toward Kaaba, but toward Jerusalem. The qibla was switched to Kaaba later on to fulfill the order of Allah of praying in the direction of Kaaba (Quran, Al-Baqarah 2:144–150). Another reason for its significance is its connection with the Miʿrāj, where, according to traditional Muslim, Muhammad ascended through the Seven heavens on a winged mule named Buraq, guided by the Archangel Gabriel, beginning from the Foundation Stone on the Temple Mount, in modern times under the Dome of the Rock.

Significance of Abraham

Even though members of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam do not all claim Abraham as an ancestor, some members of these religions have tried to claim him as exclusively theirs.

For Jews, Abraham is the founding patriarch of the children of Israel. God promised Abraham: "I will make of you a great nation, and I will bless you." With Abraham, God entered into "an everlasting covenant throughout the ages to be God to you and to your offspring to come". It is this covenant that makes Abraham and his descendants children of the covenant. Similarly, converts, who join the covenant, are all identified as sons and daughters of Abraham.

Abraham is primarily a revered ancestor or patriarch (referred to as Avraham Avinu (אברהם אבינו in Hebrew) "Abraham our father") to whom God made several promises: chiefly, that he would have numberless descendants, who would receive the land of Canaan (the "Promised Land"). According to Jewish tradition, Abraham was the first post-Flood prophet to reject idolatry through rational analysis, although Shem and Eber carried on the tradition from Noah.

Christians view Abraham as an important exemplar of faith, and a spiritual, as well as physical, ancestor of Jesus. For Christians, Abraham is a spiritual forebear as well as/rather than a direct ancestor depending on the individual's interpretation of Paul the Apostle, with the Abrahamic covenant "reinterpreted so as to be defined by faith in Christ rather than biological descent" or both by faith as well as a direct ancestor; in any case, the emphasis is placed on faith being the only requirement for the Abrahamic Covenant to apply (see also New Covenant and supersessionism). In Christian belief, Abraham is a role model of faith, and his obedience to God by offering Isaac is seen as a foreshadowing of God's offering of his son Jesus.

Christian commentators have a tendency to interpret God's promises to Abraham as applying to Christianity subsequent to, and sometimes rather than (as in supersessionism), being applied to Judaism, whose adherents rejected Jesus. They argue this on the basis that just as Abraham as a Gentile (before he was circumcised) "believed God and it was credited to him as righteousness" (cf. Rom. 4:3, James 2:23), "those who have faith are children of Abraham" (see also John 8:39). This is most fully developed in Paul's theology where all who believe in God are spiritual descendants of Abraham.However, with regards to Rom. 4:20 and Gal. 4:9, in both cases he refers to these spiritual descendants as the "sons of God" rather than "children of Abraham".

For Muslims, Abraham is a prophet, the "messenger of God" who stands in the line from Adam to Muhammad, to whom God gave revelations,[Quran %3Averse%3D163 4 :163], who "raised the foundations of the House" (i.e., the Kaaba)[Quran %3Averse%3D127 2 :127] with his first son, Isma'il, a symbol of which is every mosque. Ibrahim (Abraham) is the first in a genealogy for Muhammad. Islam considers Abraham to be "one of the first Muslims" (Surah 3)—the first monotheist in a world where monotheism was lost, and the community of those faithful to God, thus being referred to as ابونا ابراهيم or "Our Father Abraham", as well as Ibrahim al-Hanif or "Abraham the Monotheist". Also, the same as Judaism, Islam believes that Abraham rejected idolatry through logical reasoning. Abraham is also recalled in certain details of the annual Hajj pilgrimage.

Differences

God

The Abrahamic God is the conception of God that remains a common feature of all Abrahamic religions. The Abrahamic God is conceived of as eternal, omnipotent, omniscient and as the creator of the universe. God is further held to have the properties of holiness, justice, omnibenevolence, and omnipresence. Proponents of Abrahamic faiths believe that God is also transcendent, but at the same time personal and involved, listening to prayer and reacting to the actions of his creatures. God in Abrahamic religions is always referred to as masculine only.

In Jewish theology, God is strictly monotheistic. God is an absolute one, indivisible and incomparable being who is the ultimate cause of all existence. Jewish tradition teaches that the true aspect of God is incomprehensible and unknowable and that it is only God's revealed aspect that brought the universe into existence, and interacts with mankind and the world. In Judaism, the one God of Israel is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, who is the guide of the world, delivered Israel from slavery in Egypt, and gave them the 613 Mitzvot at Mount Sinai as described in the Torah.

The national god of the Israelites has a proper name, written Y-H-W-H (Hebrew: יהוה) in the Hebrew Bible. The etymology of the name is unknown. An explanation of the name is given to Moses when YHWH calls himself "I Am that I Am", (Hebrew: אהיה אשר אהיה ’ehye ’ăšer ’ehye), seemingly connecting it to the verb hayah (הָיָה), meaning 'to be', but this is likely not a genuine etymology. Jewish tradition accords many names to God, including Elohim, Shaddai, and Sabaoth.

In Christian theology, God is the eternal being who created and preserves the world. Christians believe God to be both transcendent and immanent (involved in the world). Early Christian views of God were expressed in the Pauline Epistles and the early creeds, which proclaimed one God and the divinity of Jesus.

Around the year 200, Tertullian formulated a version of the doctrine of the Trinity which clearly affirmed the divinity of Jesus and came close to the later definitive form produced by the Ecumenical Council of 381. Trinitarians, who form the large majority of Christians, hold it as a core tenet of their faith. Nontrinitarian denominations define the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit in a number of different ways.

The theology of the attributes and nature of God has been discussed since the earliest days of Christianity, with Irenaeus writing in the 2nd century: "His greatness lacks nothing, but contains all things." In the 8th century, John of Damascus listed eighteen attributes which remain widely accepted. As time passed, theologians developed systematic lists of these attributes, some based on statements in the Bible (e.g., the Lord's Prayer, stating that the Father is in Heaven), others based on theological reasoning.

In Islamic theology, God (Arabic: الله Allāh) is the all-powerful and all-knowing creator, sustainer, ordainer and judge of everything in existence. Islam emphasizes that God is strictly singular (tawḥīd) unique (wāḥid) and inherently One (aḥad), all-merciful and omnipotent. According to Islamic teachings, God exists without place and according to the Quran, "No vision can grasp him, but His grasp is over all vision: He is above all comprehension, yet is acquainted with all things." God, as referenced in the Quran, is the only God. Islamic tradition also describes the 99 names of God. These 99 names describe attributes of God, including Most Merciful, The Just, The Peace and Blessing, and the Guardian.

Islamic belief in God is distinct from Christianity in that God has no progeny. This belief is summed up in chapter 112 of the Quran titled Al-Ikhlas, which states "Say, he is Allah (who is) one, Allah is the Eternal, the Absolute. He does not beget nor was he begotten. Nor is there to Him any equivalent."[Quran %3Averse%3D1 112 :1]

Scriptures

All these religions rely on a body of scriptures, some of which are considered to be the word of God—hence sacred and unquestionable—and some the work of religious men, revered mainly by tradition and to the extent that they are considered to have been divinely inspired, if not dictated, by the divine being.

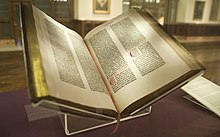

The sacred scriptures of Judaism are the Tanakh, a Hebrew acronym standing for Torah (Law or Teachings), Nevi'im (Prophets) and Ketuvim (Writings). These are complemented by and supplemented with various (originally oral) traditions: Midrash, the Mishnah, the Talmud and collected rabbinical writings. The Tanakh (or Hebrew Bible) was composed between 1,400 BCE, and 400 BCE by Jewish prophets, kings, and priests.

The Hebrew text of the Tanakh, and the Torah in particular is considered holy, down to the last letter: transcribing is done with painstaking care. An error in a single letter, ornamentation or symbol of the 300,000+ stylized letters that make up the Hebrew Torah text renders a Torah scroll unfit for use; hence the skills of a Torah scribe are specialist skills, and a scroll takes considerable time to write and check.

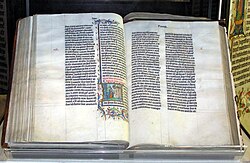

The sacred scriptures of most Christian groups are the Old Testament and the New Testament. Latin Bibles originally contained 73 books; however, 7 books, collectively called the Apocrypha or Deuterocanon depending on one's opinion of them, were removed by Martin Luther due to a lack of original Hebrew sources, and now vary on their inclusion between denominations. Greek Bibles contain additional materials.

The New Testament comprises four accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus (the Four Gospels), as well as several other writings (the epistles) and the Book of Revelation. They are usually considered to be divinely inspired, and together comprise the Christian Bible.

The vast majority of Christian faiths (including Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity, and most forms of Protestantism) recognize that the Gospels were passed on by oral tradition, and were not set to paper until decades after the resurrection of Jesus and that the extant versions are copies of those originals. The version of the Bible considered to be most valid (in the sense of best conveying the true meaning of the word of God) has varied considerably: the Greek Septuagint, the Syriac Peshitta, the Latin Vulgate, the English King James Version and the Russian Synodal Bible have been authoritative to different communities at different times.

The sacred scriptures of the Christian Bible are complemented by a large body of writings by individual Christians and councils of Christian leaders (see canon law). Some Christian churches and denominations consider certain additional writings to be binding; other Christian groups consider only the Bible to be binding (sola scriptura).

Islam's holiest book is the Quran, comprising 114 Suras ("chapters of the Qur'an"). However, Muslims also believe in the religious texts of Judaism and Christianity in their original forms, albeit not the current versions. According to the Quran (and mainstream Muslim belief), the verses of the Quran were revealed by God through the Archangel Jibrail to Muhammad on separate occasions. These revelations were written down and also memorized by hundreds of companions of Muhammad. These multiple sources were collected into one official copy. After the death of Muhammad, Quran was copied on several copies and Caliph Uthman provided these copies to different cities of Islamic Empire.

The Quran mentions and reveres several of the Israelite prophets, including Moses and Jesus, among others (see also: Prophets of Islam). The stories of these prophets are very similar to those in the Bible. However, the detailed precepts of the Tanakh and the New Testament are not adopted outright; they are replaced by the new commandments accepted as revealed directly by God (through Gabriel) to Muhammad and codified in the Quran.

Like the Jews with the Torah, Muslims consider the original Arabic text of the Quran as uncorrupted and holy to the last letter, and any translations are considered to be interpretations of the meaning of the Quran, as only the original Arabic text is considered to be the divine scripture.

Like the Rabbinic Oral Law to the Hebrew Bible, the Quran is complemented by the Hadith, a set of books by later authors recording the sayings of the prophet Muhammad. The Hadith interpret and elaborate Qur'anic precepts. Islamic scholars have categorized each Hadith at one of the following levels of authenticity or isnad: genuine (sahih), fair (hasan) or weak (da'if).

By the 9th century, six major Hadith collections were accepted as reliable to Sunni Muslims.

Shi'a Muslims, however, refer to other authenticated hadiths instead. They are known collectively as The Four Books.

The Hadith and the life story of Muhammad (sira) form the Sunnah, an authoritative supplement to the Quran. The legal opinions of Islamic jurists (Faqīh) provide another source for the daily practice and interpretation of Islamic tradition (see Fiqh.)

The Quran contains repeated references to the "religion of Abraham" (see Suras 2:130,135; 3:95; 6:123,161; 12:38; 16:123; 22:78). In the Quran, this expression refers specifically to Islam; sometimes in contrast to Christianity and Judaism, as in Sura 2:135, for example: 'They say: "Become Jews or Christians if ye would be guided (to salvation)." Say thou (O Muslims): "Nay! (I would rather) the Religion of Abraham the True, and he joined not gods with God." ' In the Quran, Abraham is declared to have been a Muslim (a hanif, more accurately a "primordial monotheist"), not a Jew nor a Christian (Sura 3:67).

Eschatology

In the major Abrahamic religions, there exists the expectation of an individual who will herald the time of the end or bring about the Kingdom of God on Earth; in other words, the Messianic prophecy. Judaism awaits the coming of the Jewish Messiah; the Jewish concept of Messiah differs from the Christian concept in several significant ways, despite the same term being applied to both. The Jewish Messiah is not seen as a "god", but as a mortal man who by his holiness is worthy of that description. His appearance is not the end of history, rather it signals the coming of the world to come.

Christianity awaits the Second Coming of Christ, though Full Preterists believe this has already happened. Islam awaits both the second coming of Jesus (to complete his life and die) and the coming of Mahdi (Sunnis in his first incarnation, Twelver Shia as the return of Muhammad al-Mahdi).

Most Abrahamic religions agree that a human being comprises the body, which dies, and the soul, which is capable of remaining alive beyond human death and carries the person's essence, and that God will judge each person's life accordingly on the Day of Judgement. The importance of this and the focus on it, as well as the precise criteria and end result, differ between religions.

Judaism's views on the afterlife ("the Next World") are quite diverse. This can be attributed to an almost non-existent tradition of souls/spirits in the Hebrew Bible (a possible exception being the Witch of Endor), resulting in a focus on the present life rather than future reward.

Christians have more diverse and definite teachings on the end times and what constitutes afterlife. Most Christian approaches either include different abodes for the dead (Heaven, Hell, Limbo, Purgatory) or universal reconciliation because all souls are made in the image of God. A small minority teach annihilationism, the doctrine that those persons who are not reconciled to God simply cease to exist.

In Islam, God is said to be "Most Compassionate and Most Merciful" (Quran 1:2, as well as the start of all Suras but one). However, God is also "Most Just"; Islam prescribes a literal Hell for those who disobey God and commit gross sin. Those who obey God and submit to God will be rewarded with their own place in Paradise. While sinners are punished with fire, there are also many other forms of punishment described, depending on the sin committed; Hell is divided into numerous levels.

Those who worship and remember God are promised eternal abode in a physical and spiritual Paradise. Heaven is divided into eight levels, with the highest level of Paradise being the reward of those who have been most virtuous, the prophets, and those killed while fighting for Allah (martyrs).

Upon repentance to God, many sins can be forgiven, on the condition they are not repeated, as God is supremely merciful. Additionally, those who believe in God, but have led sinful lives, may be punished for a time, and then eventually released into Paradise. If anyone dies in a state of Shirk (i.e. associating God in any way, such as claiming that He is equal with anything or denying Him), this is not pardonable—he or she will stay forever in Hell.

Once a person is admitted to Paradise, this person will abide there for eternity.

Worship and religious rites

Worship, ceremonies and religion-related customs differ substantially among the Abrahamic religions. Among the few similarities are a seven-day cycle in which one day is nominally reserved for worship, prayer or other religious activities—Shabbat, Sabbath, or jumu'ah; this custom is related to the biblical story of Genesis, where God created the universe in six days and rested in the seventh.

Orthodox Judaism practice is guided by the interpretation of the Torah and the Talmud. Before the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem, Jewish priests offered sacrifices there two times daily; since then, the practice has been replaced, until the Temple is rebuilt, by Jewish men being required to pray three times daily, including the chanting of the Torah, and facing in the direction of Jerusalem's Temple Mount. Other practices include circumcision, dietary laws, Shabbat, Passover, Torah study, Tefillin, purity and others. Conservative Judaism, Reform Judaism and the Reconstructionist movement all move away, in different degrees, from the strict tradition of the law.

Jewish women's prayer obligations vary by denomination; in contemporary Orthodox practice, women do not read from the Torah and are only required to say certain parts of these daily services.

All versions of Judaism share a common, specialized calendar, containing many festivals. The calendar is lunisolar, with lunar months and a solar year (an extra month is added every second or third year to allow the shorter lunar year to "catch up" to the solar year). All streams observe the same festivals, but some emphasize them differently. As is usual with its extensive law system, the Orthodox have the most complex manner of observing the festivals, while the Reform pay more attention to the simple symbolism of each one.

Christian worship varies from denomination to denomination. Individual prayer is usually not ritualised, while group prayer may be ritual or non-ritual according to the occasion. During church services, some form of liturgy is frequently followed. Rituals are performed during sacraments, which also vary from denomination to denomination and usually include Baptism and Communion, and may also include Confirmation, Confession, Last Rites and Holy Orders.

Catholic worship practice is governed by documents, including (in the largest, Western, Latin Church) the Roman Missal. Individuals, churches and denominations place different emphasis on ritual—some denominations consider most ritual activity optional (see Adiaphora), particularly since the Protestant Reformation.

The followers of Islam (Muslims) are to observe the Five Pillars of Islam. The first pillar is the belief in the oneness of Allah, and in Muhammad as his final and most perfect prophet. The second is to pray five times daily (salat) towards the direction (qibla) of the Kaaba in Mecca. The third pillar is almsgiving (Zakah), a portion of one's wealth given to the poor or to other specified causes, which means the giving of a specific share of one's wealth and savings to persons or causes, as is commanded in the Quran and elucidated as to specific percentages for different kinds of income and wealth in the hadith. The normal share to be paid is two and a half percent of one's earnings: this increases if labour was not required, and increases further if only capital or possessions alone were required (i.e. proceeds from renting space), and increases to 50% on "unearned wealth" such as treasure-finding, and to 100% on wealth that is considered haram, as part of attempting to make atonement for the sin, such as that gained through financial interest (riba).

Fasting (sawm) during the ninth month of the Muslim lunar calendar, Ramadan, is the fourth pillar of Islam, to which all Muslims after the age of puberty in good health (as judged by a Muslim doctor to be able fast without incurring grave danger to health: even in seemingly obvious situations, a "competent and upright Muslim physician" is required to agree), that are not menstruating are bound to observe—missed days of the fast for any reason must be made up, unless there be a permanent illness, such as diabetes, that prevents a person from ever fasting. In such a case, restitution must be made by feeding one poor person for each day missed.

Finally, Muslims are also required, if physically able, to undertake a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in one's life: it is strongly recommended to do it as often as possible, preferably once a year. Only individuals whose financial position and health are severely insufficient are exempt from making Hajj (e.g. if making Hajj would put stress on one's financial situation, but would not end up in homelessness or starvation, it is still required). During this pilgrimage, the Muslims spend three to seven days in worship, performing several strictly defined rituals, most notably circumambulating the Kaaba among millions of other Muslims and the "Stoning of the Devil" at Mina.

At the end of the Hajj, the heads of men are shaved, sheep and other halal animals, notably camels, are slaughtered as a ritual sacrifice by bleeding out at the neck according to a strictly prescribed ritual slaughter method similar to the Jewish kashrut, to commemorate the moment when, according to Islamic tradition, Allah replaced Abraham's son Ishmael (contrasted with the Judaeo-Christian tradition that Isaac was the intended sacrifice) with a sheep, thereby preventing human sacrifice. The meat from these animals is then distributed locally to needy Muslims, neighbours and relatives. Finally, the hajji puts off ihram and the hajj is complete.

Circumcision

Judaism and Samaritanism commands that males be circumcised when they are eight days old, as does the Sunnah in Islam. Despite its common practice in Muslim-majority nations, circumcision is considered to be sunnah (tradition) and not required for a life directed by Allah. Although there is some debate within Islam over whether it is a religious requirement or mere recommendation, circumcision (called khitan) is practiced nearly universally by Muslim males.

Today, many Christian denominations are neutral about ritual male circumcision, not requiring it for religious observance, but neither forbidding it for cultural or other reasons. Western Christianity replaced the custom of male circumcision with the ritual of baptism, a ceremony which varies according to the doctrine of the denomination, but it generally includes immersion, aspersion, or anointment with water. The Early Church (Acts 15, the Council of Jerusalem) decided that Gentile Christians are not required to undergo circumcision. The Council of Florence in the 15th century prohibited it. Paragraph #2297 of the Catholic Catechism calls non-medical amputation or mutilation immoral. By the 21st century, the Catholic Church had adopted a neutral position on the practice, as long as it is not practised as an initiation ritual. Catholic scholars make various arguments in support of the idea that this policy is not in contradiction with the previous edicts. The New Testament chapter Acts 15 records that Christianity did not require circumcision. The Catholic Church currently maintains a neutral position on the practice of non-religious circumcision, and in 1442 it banned the practice of religious circumcision in the 11th Council of Florence. Coptic Christians practice circumcision as a rite of passage. The Eritrean Orthodox Church and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church calls for circumcision, with near-universal prevalence among Orthodox men in Ethiopia.

Many countries with majorities of Christian adherents in Europe and Latin America have low circumcision rates, while both religious and non-religious circumcision is widely practiced a in many predominantly Christian countries and among Christian communities in the Anglosphere countries, Oceania, South Korea, the Philippines, the Middle East and Africa. Countries such as the United States, the Philippines, Australia (albeit primarily in the older generations), Canada, Cameroon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Nigeria, Kenya, and many other African Christian countries have high circumcision rates. Circumcision is near universal in the Christian countries of Oceania. In some African and Eastern Christian denominations male circumcision is an integral or established practice, and require that their male members undergo circumcision. Coptic Christianity and Ethiopian Orthodoxy and Eritrean Orthodoxy still observe male circumcision and practice circumcision as a rite of passage. Male circumcision is also widely practiced among Christians from South Korea, Egypt, Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Palestine, Israel, and North Africa. (See also aposthia.)

Male circumcision is among the rites of Islam and is part of the fitrah, or the innate disposition and natural character and instinct of the human creation.

Circumcision is widely practiced by the Druze, the procedure is practiced as a cultural tradition, and has no religious significance in the Druze faith. Some Druses do not circumcise their male children, and refuse to observe this "common Muslim practice".

Circumcision is not a religious practice of the Bahá'í Faith, and leaves that decision up to the parents.

Dietary restrictions

Judaism and Islam have strict dietary laws, with permitted food known as kosher in Judaism, and halal in Islam. These two religions prohibit the consumption of pork; Islam prohibits the consumption of alcoholic beverages of any kind. Halal restrictions can be seen as a modification of the kashrut dietary laws, so many kosher foods are considered halal; especially in the case of meat, which Islam prescribes must be slaughtered in the name of God. Hence, in many places, Muslims used to consume kosher food. However, some foods not considered kosher are considered halal in Islam.

With rare exceptions, Christians do not consider the Old Testament's strict food laws as relevant for today's church; see also Biblical law in Christianity. Most Protestants have no set food laws, but there are minority exceptions.

The Roman Catholic Church believes in observing abstinence and penance. For example, all Fridays through the year and the time of Lent are penitential days. The law of abstinence requires a Catholic from 14 years of age until death to abstain from eating meat on Fridays in honor of the Passion of Jesus on Good Friday. The United States Conference of Catholic Bishops obtained the permission of the Holy See for Catholics in the U.S. to substitute a penitential, or even a charitable, practice of their own choosing. Eastern Rite Catholics have their own penitential practices as specified by the Code of Canons for the Eastern Churches.

The Seventh-day Adventist Church (SDA) embraces numerous Old Testament rules and regulations such as tithing, Sabbath observance, and Jewish food laws. Therefore, they do not eat pork, shellfish, or other foods considered unclean under the Old Covenant. The "Fundamental Beliefs" of the SDA state that their members "are to adopt the most healthful diet possible and abstain from the unclean foods identified in the Scriptures".

In the Christian Bible, the consumption of strangled animals and of blood was forbidden by Apostolic Decree and are still forbidden in the Greek Orthodox Church, according to German theologian Karl Josef von Hefele, who, in his Commentary on Canon II of the Second Ecumenical Council held in the 4th century at Gangra, notes: "We further see that, at the time of the Synod of Gangra, the rule of the Apostolic Synod [the Council of Jerusalem of Acts 15] with regard to blood and things strangled was still in force. With the Greeks, indeed, it continued always in force as their Euchologies still show." He also writes that "as late as the eighth century, Pope Gregory the Third, in 731, forbade the eating of blood or things strangled under threat of a penance of forty days."

Jehovah's Witnesses abstain from eating blood and from blood transfusions based on Acts 15:19–21.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints prohibits the consumption of alcohol, coffee, and non-herbal tea. While there is not a set of prohibited food, the church encourages members to refrain from eating excessive amounts of red meat.

Sabbath observance

Sabbath in the Bible is a weekly day of rest and time of worship. It is observed differently in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam and informs a similar occasion in several other Abrahamic faiths. Though many viewpoints and definitions have arisen over the millennia, most originate in the same textual tradition.

Proselytism

Judaism accepts converts, but has had no explicit missionaries since the end of the Second Temple era. Judaism states that non-Jews can achieve righteousness by following Noahide Laws, a set of moral imperatives that, according to the Talmud, were given by God as a binding set of laws for the "children of Noah"—that is, all of humanity. It is believed that as much as ten percent of the Roman Empire followed Judaism either as fully ritually obligated Jews or the simpler rituals required of non-Jewish members of that faith.

Moses Maimonides, one of the major Jewish teachers, commented: "Quoting from our sages, the righteous people from other nations have a place in the world to come if they have acquired what they should learn about the Creator." Because the commandments applicable to the Jews are much more detailed and onerous than Noahide laws, Jewish scholars have traditionally maintained that it is better to be a good non-Jew than a bad Jew, thus discouraging conversion. In the U.S., as of 2003 28% of married Jews were married to non-Jews. See also Conversion to Judaism.

Christianity encourages evangelism. Many Christian organizations, especially Protestant churches, send missionaries to non-Christian communities throughout the world. See also Great Commission. Forced conversions to Catholicism have been alleged at various points throughout history. The most prominently cited allegations are the conversions of the pagans after Constantine; of Muslims, Jews and Eastern Orthodox during the Crusades; of Jews and Muslims during the time of the Spanish Inquisition, where they were offered the choice of exile, conversion or death; and of the Aztecs by Hernán Cortés. Forced conversions to Protestantism may have occurred as well, notably during the Reformation, especially in England and Ireland (see recusancy and Popish plot).

Forced conversions are now condemned as sinful by major denominations such as the Roman Catholic Church, which officially states that forced conversions pollute the Christian religion and offend human dignity, so that past or present offences are regarded as a scandal (a cause of unbelief). According to Pope Paul VI, "It is one of the major tenets of Catholic doctrine that man's response to God in faith must be free: no one, therefore, is to be forced to embrace the Christian faith against his own will." The Roman Catholic Church has declared that Catholics should fight anti-Semitism.

Dawah is an important Islamic concept which denotes the preaching of Islam. Da‘wah literally means "issuing a summons" or "making an invitation". A Muslim who practices da‘wah, either as a religious worker or in a volunteer community effort, is called a dā‘ī, plural du‘āt. A dā‘ī is thus a person who invites people to understand Islam through a dialogical process and may be categorized in some cases as the Islamic equivalent of a missionary, as one who invites people to the faith, to the prayer, or to Islamic life.

Da'wah activities can take many forms. Some pursue Islamic studies specifically to perform Da'wah. Mosques and other Islamic centers sometimes spread Da'wah actively, similar to evangelical churches. Others consider being open to the public and answering questions to be Da'wah. Recalling Muslims to the faith and expanding their knowledge can also be considered Da'wah.

In Islamic theology, the purpose of Da‘wah is to invite people, both Muslims and non-Muslims, to understand the commandments of God as expressed in the Quran and the Sunnah of the Prophet, as well as to inform them about Muhammad. Da‘wah produces converts to Islam, which in turn grows the size of the Muslim Ummah, or community of Muslims.

Dialogue between Abrahamic religions

This section reports on writings and talks which describe or advocate dialogue between the Abrahamic religions.

Amir Hussain

In 2003, a book titled Progressive Muslims: On Justice, Gender, and Pluralism contains a chapter by Amir Hussain

which is titled "Muslims, Pluralism, and Interfaith Dialogue" in which

he claims that interfaith dialogue has been an integral part of Islam

since its origin. After he received his "first revelation" and for the

rest of his life, Muhammad was "engaged in interfaith dialogue". Islam

would not have spread without "interfaith dialogue".

Hussain gives an early example of "the importance of pluralism and interfaith dialogue" in Islam. After some of Muhammad's followers were subjected to "physical persecution" in Mecca, he sent them to Abyssinia, a Christian nation, where they were "welcomed and accepted" by the Christian king. Another example is Córdoba, Andalusia in Muslim Spain, in the ninth and tenth centuries. Córdoba was "one of the most important cities in the history of the world". In Córdoba, "Christians and Jews were involved in the Royal Court and the intellectual life of the city." Thus, there is "a history of Muslims, Jews, Christians, and other religious traditions living together in a pluralistic society".

Turning to the present, Hussain says that one of the challenges which Muslims currently face is the conflicting passages in the Qur̀an some of which support interfaith "bridge-building", but other passages of it can be used to "justify mutual exclusion".

Trialogue

The 2007 book Trialogue: Jews, Christians, and Muslims in Dialogue starkly states the importance of interfaith dialogue: "We human beings today face a stark choice: dialogue or death!" The Trialogue book gives four reasons why the three Abrahamic religions should engage in dialogue:

- 1. They "come from the same Hebraic roots and claim Abraham as their originating ancestor".

- 2. "All three traditions are religions of ethical monotheism."

- 3. They "are all historical religions".

- 4. All three are "religions of revelation".

Pope Benedict XVI

In 2010, Pope Benedict XVI spoke about "Interreligious dialogue". He said that "the Church's universal nature and vocation require that she engage in dialogue with the members of other religions." For the Abrahamic religions, this "dialogue is based on the spiritual and historical bonds uniting Christians to Jews and Muslims". It is dialogue "grounded in the sacred Scriptures" and "defined in the Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen Gentium and in the Declaration on the Church's Relation to Non-Christian Religions Nostra Aetate. The Pope concluded with a prayer: "May Jews, Christians and Muslims ... give the beautiful witness of serenity and concord between the children of Abraham."

Learned Ignorance

In the 2011 book Learned Ignorance: Intellectual Humility Among Jews, Christians and Muslims, the three editors address the question of "why engage in interreligious dialogue; its purpose?":

- James L. Heft, a Roman Catholic priest, suggests "that the purpose of interreligious dialogue is, not only better mutual understanding ... but also trying ... to embody the truths that we affirm."

- Omid Safi, a Muslim, answers the question of "why engage in interreligious dialogue?" He writes, "because for me, as a Muslim, God is greater than any one path leading to God". Therefore, "neither I nor my traditions has a monopoly on truth, because in reality, we belong to the Truth (God), Truth to us."

- Reuven Firestone, a Jewish rabbi writes about the "tension" between the "particularity" of one's "own religious experience" and the "universality of the divine reality" that as expressed in history has led to verbal and violent conflict. So, although this tension may never be "fully resolved", Firestone says that "it is of utmost consequence for leaders in religion to engage in the process of dialogue."

The Interfaith Amigos

In 2011, TED broadcast a 10-minute program about "Breaking the Taboos of Interfaith Dialogue" with Rabbi Ted Falcon (Jewish), Pastor Don Mackenzie (Christian), and Imam Jamal Rahman (Muslim) collectively known as The Interfaith Amigos. See their TED program by clicking here.

Divisive matters should be addressed

In 2012, a PhD thesis Dialogue Between Christians, Jews and Muslims argues that "the paramount need is for barriers against non-defensive dialogue conversations between Christians, Jews, and Muslims to be dismantled to facilitate the development of common understandings on matters that are deeply divisive." As of 2012, the thesis says that this has not been done.

Cardinal Koch

In 2015, Cardinal Kurt Koch, the President of the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, an organization that is "responsible for the Church's dialogue with the Jewish people", was interviewed. He noted that the Church is already engaging in "bilateral talks with Jewish and Muslim religious leaders" but stated that it is too early for the Church to host "trialogue" talks with representatives of the three Abrahamic religions. Yet, Koch added, "we hope that we can go in this [direction] in the future."

Omid Safi

In 2016, a 26-minute interview with Omid Safi, a Muslim and Director of the Duke Islamic Studies Center, was posted on YouTube. In it, Safi stated that he has spent his life trying to combine "love and tenderness" which are the "essence of being human" with "social justice".

Ahmed el-Tayeb

In November 2021, Ahmed el-Tayeb announced the rejection of the call to the "new Abrahamic religion", and asked in his speech whether the call was intended to "cooperate with believers in religions on their common and noble human values, or is it intended to create a new religion that has no color, taste, or smell", as he put it. Al-Tayeb said that the call to "Ibrahimism" "appears to be a call for human unity and the elimination of the causes of disputes and conflicts, and in fact it is a call to confiscate freedom of belief, freedom of faith and choice".

Al-Tayeb believes that the call to unite the religion is a call that is "closer to troubled dreams than to realizing the facts and nature of things", because "the meeting of creation on one religion is impossible in the habit that God created people with." He continued, saying that "respecting the faith of the other is one thing, and believing in it is another".

Demographics

Worldwide percentage of adherents by Abrahamic religion, as of 2015

Christianity is the largest Abrahamic religion with about 2.3 billion adherents, constituting about 31.1% of the world's population. Islam is the second largest Abrahamic religion, as well as the fastest-growing Abrahamic religion in recent decades. It has about 1.9 billion adherents, called Muslims, which constitute about 24.1% of the world's population. The third largest Abrahamic religion is Judaism with about 14.1 million adherents, called Jews. The Baháʼí Faith has over 8 million adherents, making it the fourth largest Abrahamic religion, and the fastest growing religion across the 20th century usually at least twice the rate of population growth. The Druze Faith has between one million and nearly two millions adherents.

| Religion | Adherents |

|---|---|

| Baháʼí | ~8 million |

| Druze | 1–2 million |

| Rastafari | 700,000-1 million |

| Mandaeism | 60,000–100,000 |

| Azali Bábism | ~1,000–2,000 |

| Samaritanism | ~840 |