After the initial outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), conspiracy theories and misinformation spread online regarding the origin and scale, and various other aspects of the disease. Various social media posts claimed the virus was a bio-weapon with a patented vaccine, a population control scheme, or the result of a spy operation.

Efforts to combat misinformation

On 2 February, the World Health Organization

(WHO) declared a "massive infodemic", citing an over-abundance of

reported information, accurate and false, about the virus that "makes it

hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when

they need it." The WHO stated that the high demand for timely and

trustworthy information has incentivised the creation of a direct WHO

24/7 myth-busting hotline where its communication and social media teams

have been monitoring and responding to misinformation through its

website and social media pages.

Facebook, Twitter and Google said they were working with WHO to address "misinformation".

In a blogpost, Facebook stated they would remove content flagged by

leading global health organizations and local authorities that violate

its content policy on misinformation leading to "physical harm". Facebook are also giving free advertising to WHO.

At the end of February, Amazon

banned over a million products that wrongly claimed to be able to cure

or protect against coronavirus. They also removed tens of thousands of

listings for overpriced health products.

Human made

Chinese biological weapon

In January 2020, the BBC published an article about coronavirus misinformation, citing two 24 January articles from the The Washington Times which claimed the virus was part of a Chinese biological weapons program, based at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). The Washington Post

later published an article debunking the conspiracy theory, citing U.S.

experts who explained why the Institute was not suitable for bioweapon

research, that most countries had abandoned bioweapons as fruitless, and

that there was no evidence that the virus was genetically engineered.

In February 2020, U.S. Senator Tom Cotton (R-AR) as well as Francis Boyle, a law professor, suggested that the virus may have been a Chinese bioweapon, while in the opinion of numerous medical experts there is no evidence for this. Conservative political commentator Rush Limbaugh

said the virus was probably "a ChiCom laboratory experiment" and that

the Chinese were weaponizing the virus and media hysteria surrounding it

to bring down Donald Trump, on the most-listened-to radio show in US. In February 2020, The Financial Times

reported from virus expert and global co-lead coronavirus investigator,

Trevor Bedford, who said that "There is no evidence whatsoever of

genetic engineering that we can find", and that, "The evidence we have

is that the mutations [in the virus] are completely consistent with

natural evolution".

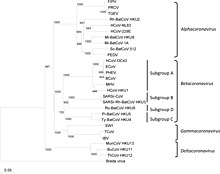

Bedford further explained, "The most likely scenario, based on genetic

analysis, was that the virus was transmitted by a bat to another mammal

between 20–70 years ago. This intermediary animal—not yet

identified—passed it on to its first human host in the city of Wuhan in

late November or early December 2019".

On 29 January, financial news website and blog ZeroHedge

suggested, without evidence, that a scientist at the WIV created the

COVID-19 strain responsible for the coronavirus outbreak. Zerohedge

listed the full contact details of the scientist supposedly responsible,

a practice known as doxing,

by including the scientist's name, photo and phone number, suggesting

to readers that they "pay [the Chinese scientist] a visit" if they

wanted to know "what really caused the coronavirus pandemic". Twitter later permanently suspended the blog's account for violating its platform manipulation policy.

Zerohedge has since claimed the article did not claim the virus was

human-made and that it only publicised publicly available details of the

scientist.

Logo of Umbrella Corporation

In January 2020, Buzzfeed News also reported on an internet meme/conspiracy theory of a link between the logo of the Wuhan Institute of Virology and "Umbrella Corporation", the agency that made the virus that starts the zombie apocalypse in the Resident Evil franchise. The theory also saw a link between "Racoon" (the main city in Resident Evil), and an anagram of "Corona" (the name of the virus). The popularity of this theory attracted the attention of Snopes,

who proved it as false showing that the logo was not from the

Institute, but from Shanghai Ruilan Bao Hu San Biotech Limited, located

approximately 500 miles (800 km) away in Shanghai and additionally

pointed out that the proper name of the city in Resident Evil is Raccoon

City.

The Inverse reported that "Christopher Bouzy, the founder of Bot Sentinel, did a Twitter analysis for Inverse and found [online] bots and trollbots

are making an array of false claims. These bots are claiming China

intentionally created the virus, that it's a biological weapon, that

Democrats are overstating the threat to hurt Donald Trump and more.

While we can't confirm the origin of these bots, they are decidedly

pro-Trump."

Misinformation aside, concerns on accidental leakage by the WIV remain. In 2017, U.S. molecular biologist Richard H. Ebright, expressed caution when the WIV was expanded to become mainland China's first biosafety level 4 (BSL–4) laboratory, noting previous escapes of the SARS virus at other Chinese laboratories.

While Ebright refuted several conspiracy theories regarding the WIV

(e.g. bioweapons research, that the virus was engineered), he told BBC

China that this did not represent the possibility of the virus being

"completely ruled out" from entering the population due to a laboratory

accident.

On 6 February, the White House asked scientists and medical researchers

to rapidly investigate the origins of the virus in order to address

both the current spread and "to inform future outbreak preparation and

better understand animal/human and environmental transmission aspects of

coronaviruses."

Tobias Elwood M.P. and Chairman of the British Defence Select

Committee, also publicly questioned the role of the Chinese Army's Wuhan

Institute for Biological Products and called for the "greater

transparency over the origins of the coronavirus".

South China Morning Post reported that one of the Institute's lead researchers, Shi Zhengli,

was the particular focus of personal attacks in Chinese social media

who alleged her work on bat-based viruses as the source of the virus,

leading Shi to post: "I swear with my life, [the virus] has nothing to

do with the lab", and when asked by the SCMP to comment on the attacks, Shi responded: "My time must be spent on more important matters". Caixin reported Shi made further public statements against "perceived tinfoil-hat

theories about the new virus's source", quoting her as saying: "The

novel 2019 coronavirus is nature punishing the human race for keeping

uncivilized living habits. I, Shi Zhengli, swear on my life that it has

nothing to do with our laboratory".

US biological weapon

On 3 March, US Senator Marco Rubio, member of the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence and Committee on Foreign Relations,

claimed that "malign actors in Beijing, Moscow, Tehran and elsewhere

are exploiting the coronavirus pandemic to sow chaos through conspiracy

theories – most heinously, the notion that the United States created the

disease". He claimed that those states are "waging disinformation warfare over coronavirus".

Russian accusation

On

22 February, US officials alleged that Russia is behind an ongoing

disinformation campaign, using thousands of social media accounts on

Twitter, Facebook, Instagram to deliberately promote unfounded conspiracy theories, claiming that the virus is a biological weapon manufactured by the CIA and the US is waging economic war on China using the virus. The acting assistant secretary of state for Europe and Eurasia, Philip Reeker,

said that "Russia's intent is to sow discord and undermine US

institutions and alliances from within" and "by spreading disinformation

about coronavirus, Russian malign actors are once again choosing to

threaten public safety by distracting from the global health response". Russia denies the allegation, saying "this is a deliberately false story".

According to US-based The National Interest

magazine, although official Russian channels had been muted on pushing

the US biowarfare conspiracy theory, other Russian media elements don't

share the Kremlin's restraint.

Zvezda, a news outlet funded by the Russian Defense Ministry, published

an article titled "Coronavirus: American biological warfare against

Russia and China", claiming that the virus is intended to damage the

Chinese economy, weakening its hand in the next round of trade

negotiations. Ultra-nationalist politician and leader of the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia, Vladimir Zhirinovsky, claimed on a Moscow radio station that the virus was an experiment by the Pentagon

and pharmaceutical companies. Politician Igor Nikulin made rounds on

Russian television and news media, arguing that Wuhan was chosen for the

attack because the presence of a BSL-4 virus lab provided a cover story

for the Pentagon and CIA about a Chinese bio-experiment leak.

Iranian accusation

According to Radio Farda, Iranian cleric Seyyed Mohammad Saeedi accused US President Donald Trump of targeting Qom with coronavirus "to damage its culture and honor." Saeedi claimed that "by targeting Qom, Trump is fulfilling his promise of hitting Iranian cultural sites if Iranians took revenge for the U.S. killing of Quds Force Commander Qassem Soleimani.

Iranian researcher Ali Akbar Raefipour claimed that the

coronavirus was part of a "hybrid warfare" programme waged by the United

States on Iran and China.

Brigadier General Gholam Reza Jalali, head of Iranian Civil

Defense Organization, claimed that the coronavirus is likely biological

attack on China and Iran with economic goals.

Hossein Salami, the head of Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), claimed that the coronavirus outbreak in Iran may be due to a US "biological attack".

Chinese accusation

According to London-based The Economist, conspiracy theories about COVID-19 being the CIA's creation to keep China down are all over the Chinese internet.

Multiple conspiracy articles in Chinese from SARS-era resurfaced

during the outbreak with altered details, claiming that SARS is

biological warfare conducted by America against China. Some of these

articles claim that BGI Group

from China sold genetic information of the Chinese race to America,

with America then being able to deploy the virus specifically targeting

the gene of Chinese individuals.

On 26 January, Chinese military news site Xilu published an

article detailing how the virus was artificially combined by America to

"precisely target Chinese people". The article was removed after early February.

Some articles on popular sites in Chinese have also cast suspicion on US military athletes participating in the Wuhan 2019 Military World Games

which lasted until the end of October 2019 to have deployed the virus.

They claim the inattentive attitude and disproportionately below average

results of American athletes in the game indicate they might have been

in for other purposes and they might actually be bio-warfare operatives,

and that their place of residence during their stay in Wuhan was also

close to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market, where the first known cluster of cases occurred.

Arab world

According to Washington D.C.-based nonprofit Middle East Media Research Institute,

numerous writers in the Arabic press have promoted the conspiracy

theory that COVID-19, as well as SARS and the swine flu virus, were

deliberately created and spread by the US to make a profit on selling

vaccines against these diseases, and it is "part of an economic and

psychological war waged by the U.S. against China with the aim of

weakening it and presenting it as a backward country and a source of

diseases". Iraqi political analyst Sabah Al-Akili on Al-Etejah TV, Saudi daily Al-Watan writer Sa'ud Al-Shehry, Syrian daily Al-Thawra

columnist Hussein Saqer, and Egyptian journalist Ahmad Rif'at on

Egyptian news website Vetogate, were some examples given by MEMRI as the

propagation of the US biowarfare conspiracy theory in the Arabic world.

Philippines

Filipino Senator, Tito Sotto,

played a bioweapon conspiracy video in a February Senate hearing,

suggesting that the coronavirus is biowarfare waged against China.

Spy operation

Some

people have alleged that the coronavirus was stolen from a Canadian

virus research lab by Chinese scientists, citing a news article by the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) in July 2019.

The CBC claimed their early report was distorted by misinformation, and

that Eric Morrissette, chief of media relations for Health Canada and

the Public Health Agency of Canada said that conspiracy theory had "no

factual basis". Further, while the Chinese scientists had sent disease

samples back to Beijing, neither sample sent during the 31 March 2019

transfer from Winnipeg, Canada to Beijing, China, was the current

coronavirus. The current location of the missing Chinese researchers is

confidential pending investigation by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

There is also no publicly available proof that the missing Chinese

scientists were responsible for sending the pathogens to China. In the midst of the coronavirus epidemic, a senior research associate and expert in biological warfare with the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies, referring to a NATO

press conference, identified suspicions of espionage as the reason

behind the expulsions from the lab, but made no suggestion that

coronavirus was taken from the Canadian lab or that it is the result of

bioweapons defense research in China.

Population control scheme

According to the BBC, Jordan Sather, a conspiracy theory YouTuber supporting the far-right QAnon conspiracy theory and the anti-vax movement, has falsely claimed the outbreak was a population control scheme created by Pirbright Institute in England, and by former Microsoft CEO Bill Gates.

Sam Hyde

A hoax post on Facebook claimed that Sam Hyde,

who is described as an international biological weapons terrorist, was

behind the outbreak. Hyde, a comedian, had previously been blamed for

over a dozen mass shootings as part of a long-running meme.

Size of the outbreak

Nurse whistleblower

On 24 January, a video circulated online appearing to be of a nurse named Jin Hui in Hubei

describing a far more dire situation in Wuhan than purported by Chinese

officials. The video claimed that more than 90,000 people had been

infected with the virus in China, the virus can spread from one person

to 14 people and the virus is starting the second mutation.

The video attracted millions of views on various social media platforms

and was mentioned in numerous online reports. However, the BBC noted

that contrary to its English subtitles in one of the video's existing

versions, the woman does not claim to be either a nurse or a doctor in

the video and that her suit and mask do not match the ones worn by

medical staff in Hubei. The video's claim of 90,000 infected cases is noted to be 'unsubstantiated'.

Alleged leak of death toll

On 25 February, Taiwan News published an article, claiming Tencent accidentally leaked the real numbers of death and infection in China. Taiwan News suggests the Tencent Epidemic Situation Tracker

had briefly showed infected cases and death tolls many times higher of

the official figure, citing a Facebook post by 38-year-old Taiwanese

beverage store owner Hiroki Lo and an anonymous Taiwanese netizen. The article was referenced by other news outlets such as Daily Mail

and widely circulated on Twitter, Facebook, 4chan, sparked a wide range

of conspiracy theories that the screenshot indicates the real death

toll instead of the ones published by health officials. Justin Lessler,

associate professor at the Bloomberg School of Public Health, claims the

numbers of the alleged "leak" are unreasonable and unrealistic, citing

the case fatality rate as far lower than the 'leaked information'. A

spokesman of Tencent responded to the news article, claiming the image

was doctored, and it features "false information which we never

published".

Keoni Everington, author of the original news article, defended and asserted the authenticity of the leak.[61] Brian Hioe and Lars Wooster of New Bloom Magazine

debunked the theory from data on other websites, which were using

Tencent's database to generate custom visualizations while showing none

of the inflated figures appearing in the images promulgated by Taiwan News. Thus, they concluded the screenshot was digitally fabricated.

Misinformation against Taiwan

On 26 February 2020, Taiwan Central News Agency

reported large amount of misinformation has appeared on Facebook,

claiming the epidemic in Taiwan has lost control, the Taiwanese

Government was covering up the total number of cases, and the Taiwanese

President Tsai Ing-wen had been infected. The Taiwan fact-check organization has suggests the misinformation on Facebook shares similarity of using simplified Chinese,

mainland China vocabulary, and unconfirmed sources. Taiwan fact check

organization warns the purpose of the misinformation is to attack the

government.

In March 2020 Taiwan's Ministry of Justice Investigation Bureau

warned that the People's Republic of China (PRC) was trying to

undermine trust in factual news by portraying official Taiwanese

Government reports as fake news. Taiwanese authorities are investigating

whether these messages was linked to instructions given by the

Communist Party. The PRC's Taiwan Affairs Office refuted the claims calling them lies and said that Taiwan's Democratic Progressive Party was "inciting hatred" between the two sides.

Vaccine and treatment

Vaccines existed

It

was reported that multiple social media posts have promoted a

conspiracy theory claiming the virus was known and that a vaccine was

already available. PolitiFact and FactCheck.org

noted that no vaccine currently exists for COVID-19. The patents cited

by various social media posts reference existing patents for genetic

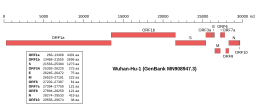

sequences and vaccines for other strains of coronavirus such as the SARS coronavirus.

The WHO reported as of 5 February 2020 that amid news reports of

"breakthrough" drugs being discovered to treat people infected with the

virus, there were no known effective treatments; this included antibiotics and herbal remedies not being useful.

Non-vaccine treatments

Traditional Chinese medicine

Chinese health authorities heavily promote the use of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) against the disease.

On 23 February 2020, Chinese president Xi Jinping called for enhanced usage of traditional Chinese medicine together with modern medicine on treating severe patients.

Various national and party-held media have heavily advertised a Wuhan Institute of Virology and Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica, Chinese Academy of Sciences report on how Shuanghuanglian,

a herb mixture from traditional Chinese medicine, can effectively

inhibit the novel coronavirus in an overnight research. The report has

led to a buying crazes of the medicine.

Despite voices of doubts, Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica confirm

they, together with Wuhan Institute of Virology, have proven the

medicine's effect on inhibiting the virus in vitro.

Jiangxia Fangcang temporary hospital, an emergency hospital in

Wuhan set up to treat the novel coronavirus patients, have let their

patients practice Chinese martial arts like Tai Chi and Ba Duan Jin (a form of Qigong) to improve their health.

India

Some politicians of India like Swami Chakrapani and Suman Haripriya claimed that drinking cow urine and applying cow dung on the body can cure coronavirus. WHO's chief scientist Soumya Swaminathan rubbished such claims and criticized these politicians for spreading misinformation.

Others

On 27 February 2020, the Estonian Minister of the Interior Mart Helme stated at a government press conference that the common cold had been renamed as the coronavirus

and that in his youth nothing like that existed. He recommended wearing

warm socks and mustard patches as well as spreading goose fat on one's

chest as treatments for the virus. Helme also said that the virus would

pass within a few days to a week just like the common cold.

Some QAnon proponents, including Jordan Stather, and others, have promoted gargling "Miracle Mineral Supplement" (actually an industrial bleach) as a way of preventing or curing the disease.

In February 2020, televangelist Jim Bakker promoted a colloidal silver solution sold on his website, as a remedy for coronavirus COVID-19; naturopath

Sherrill Sellman, a guest on his show, falsely stated that it "hasn't

been tested on this strain of the coronavirus, but it's been tested on

other strains of the coronavirus and has been able to eliminate it

within 12 hours."

Following the first reported case of COVID-19 in Nigeria on 28

February, untested cures and treatments began to spread via platforms

like WhatsApp.

African resistance

Beginning

on 11 February, reports, quickly spread via Facebook, implied that a

Cameroonian student in China had been completely cured of the virus due

to his African genetics. While a student was successfully treated, other

media sources have noted that no evidence implies Africans are more

resistant to the virus and labeled such claims as false information.

Misinformation by intergovernmental agencies

International Civil Aviation Organization

International Civil Aviation Organization

(ICAO), a civil aviation agency that belongs to the United Nations, has

rejected Taiwan's participation amid the novel coronavirus outbreak,

which has affected Taiwan's ability to gather information from the

international organization. In response to public inquiry on the

organization's decision over social media platform Twitter, ICAO commented that their action is intended to "defend the integrity of the information". United Nations Secretary General have described those inquiry as an misinformation campaign targeting ICAO.

World Health Organization

The World Health Organization lists Taiwan as part of China,

which resulted in multiple countries including Italy, Vietnam and the

Philippines briefly banning flights from Taiwan in January and February

2020, despite the disease have not reached epidemic status in Taiwan

during this period of time.

Misinformation by governments

China

Whistleblowing from various Chinese doctors, including Li Wenliang

on 30 December 2019 revealed that Wuhan hospital authorities were

already aware that the virus was a SARS-like coronavirus and patients

were already placed under quarantine.

However, news of the outbreak was also dismissed as "rumour mongering"

by the Wuhan Public Security Bureau on 3 January 2020, with admonitions

given to the individuals responsible. The Wuhan Health Commission still insisted that the illness spreading in Wuhan at the time was not SARS on 5 January 2020. An article published by a magazine owned by China News Service revealed that information had been suppressed during the beginning of the outbreak.

In the early stages of the outbreak, Chinese National Health

Commission said that they had no "clear evidence" of human-to-human

transmissions.

Later research published on 20 January 2020 indicated that among

officially confirmed cases, human-to-human transmission may have started

in December of the previous year, and the delay of disclosure on the

results until then, rather than earlier in January, was met with

criticism towards health authorities. Wang Guangfa, one of the health officials, said that "There was uncertainty regarding the human-to-human transmission", but he was infected by a patient within 10 days of making the statement.

According to the Daily Beast, on 27 January, the editor of

state-owned People's Daily tweeted an image of an apartment building

and wrongly claimed that it was a hospital under construction in Wuhan,

and that it have been completed "in 16 hours". The image was later

retweeted by a deputy minister in China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

On 15 February 2020, China's paramount leader and party general secretary Xi Jinping

published an article which claimed he had been aware of the epidemic

since 7 January 2020 and issued an order to contain the spread of the

disease during a meeting on that day. However, a record of that same

meeting released beforehand shows that there was zero mention of the

epidemic throughout.

United States

U.S. President Donald Trump and his top economic adviser Larry Kudlow

have been accused of spreading misinformation about the coronavirus. On

25 February, Trump said, "I think that whole situation will start

working out. We’re very close to a vaccine." In reality, SARS-CoV-2 has been "community-spreading" in the United States undetected for weeks, and new vaccine development may require a minimum of a year to prove safety and efficacy to gain regulatory approval. In an interview with Sean Hannity on 4 March, Trump also claimed that the death rate published by the WHO is false, that the potential impact of the outbreak is exaggerated by Democrats plotting against him, and that it is safe for infected individuals to go to work. In a later tweet, Trump denied he made claims regarding infected individuals going to work, despite footage from the interview.

The White House also has alleged the media has intentionally stoked fears of the virus to destabilize the administration. The Stat News reported that "President Trump and members of his administration

have also said that U.S. containment of the virus is 'close to

airtight' and that the virus is only as deadly as the seasonal flu.

Their statements range from false to unproven, and in some cases,

underestimate the challenges that public health officials must contend

with in responding to the virus." About the same time that “airtight” claim was made, the first case of community spread of SARS-CoV-2 was confirmed, which is spreading faster than severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus with a case fatality rate at least seven times the fatality rate for seasonal flu.

In the first week of March, after the World Health Organization reported that the case fatality rate

for COVID-19 increased from the previous estimate of around 2% to 3.4%,

Trump baselessly claimed the correct fatality rate is less than 1%, and

said, "Well, I think the 3.4% is really a false number."

Diet

Eating bats

Some media outlets, including Daily Mail and RT,

and individuals spread misinformation by promoting a video showing a

young Chinese woman biting into a bat, falsely suggesting it was shot in

Wuhan and that the outbreak was due to locals eating bats. The widely circulated video features unrelated footage of Chinese travel vlogger Wang Mengyun eating bat soup in the island country Palau in 2016 as part of an online travel programme. Wang made an apology post on Weibo, where she revealed that she was inundated with abuse, such as death threats, and that she only wished to showcase local Palauan cuisine.

Eating meat

Some organizations and individuals, including PETA, made false claims on social media that eating meat made people susceptible to the virus.

In India, a false rumour spread online alleging that only people who

eat meat were affected by coronavirus, causing "#NoMeat_NoCoronaVirus"

to trend on Twitter.

Misrepresented World Population Project map

In

early February, a decade-old map illustrating a hypothetical viral

outbreak published by the World Population Project (part of the University of Southampton) was misappropriated by a number of Australian media news outlets (including The Sun, Daily Mail and Metro)

which claimed the map represented the 2020 coronavirus outbreak. This

misinformation was then spread via the social media accounts of the same

media outlets, and while some outlets later removed the map, the BBC

reported that a number of news sites had not retracted the map yet.