Organic farming is an agricultural system which originated early in the 20th century in reaction to rapidly changing farming practices. Certified organic agriculture accounts for 70 million hectares globally, with over half of that total in Australia. Organic farming continues to be developed by various organizations today. It is defined by the use of fertilizers of organic origin such as compost manure, green manure, and bone meal and places emphasis on techniques such as crop rotation and companion planting. Biological pest control, mixed cropping and the fostering of insect predators are encouraged. Organic standards are designed to allow the use of naturally occurring substances while prohibiting or strictly limiting synthetic substances. For instance, naturally occurring pesticides such as pyrethrin and rotenone are permitted, while synthetic fertilizers and pesticides are generally prohibited. Synthetic substances that are allowed include, for example, copper sulfate, elemental sulfur and Ivermectin. Genetically modified organisms, nanomaterials, human sewage sludge, plant growth regulators, hormones, and antibiotic use in livestock husbandry are prohibited. Organic farming advocates claim advantages in sustainability, openness, self-sufficiency, autonomy/independence, health, food security, and food safety.

Organic agricultural methods are internationally regulated and legally enforced by many nations, based in large part on the standards set by the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM), an international umbrella organization for organic farming organizations established in 1972. Organic agriculture can be defined as "an integrated farming system that strives for sustainability, the enhancement of soil fertility and biological diversity while, with rare exceptions, prohibiting synthetic pesticides, antibiotics, synthetic fertilizers, genetically modified organisms, and growth hormones".

Since 1990, the market for organic food and other products has grown rapidly, reaching $63 billion worldwide in 2012. This demand has driven a similar increase in organically managed farmland that grew from 2001 to 2011 at a compounding rate of 8.9% per annum.

As of 2019, approximately 72,300,000 hectares (179,000,000 acres) worldwide were farmed organically, representing approximately 1.5 percent of total world farmland.

History

|

Agriculture was practiced for thousands of years without the use of artificial chemicals. Artificial fertilizers were first created during the mid-19th century. These early fertilizers were cheap, powerful, and easy to transport in bulk. Similar advances occurred in chemical pesticides in the 1940s, leading to the decade being referred to as the 'pesticide era'. These new agricultural techniques, while beneficial in the short term, had serious longer term side effects such as soil compaction, erosion, and declines in overall soil fertility, along with health concerns about toxic chemicals entering the food supply. In the late 1800s and early 1900s, soil biology scientists began to seek ways to remedy these side effects while still maintaining higher production.

In 1921 the founder and pioneer of the organic movement Albert Howard and his wife Gabrielle Howard, accomplished botanists, founded an Institute of Plant Industry to improve traditional farming methods in India. Among other things, they brought improved implements and improved animal husbandry methods from their scientific training; then by incorporating aspects of Indian traditional methods, developed protocols for the rotation of crops, erosion prevention techniques, and the systematic use of composts and manures. Stimulated by these experiences of traditional farming, when Albert Howard returned to Britain in the early 1930s he began to promulgate a system of organic agriculture.

In 1924 Rudolf Steiner gave a series of eight lectures on agriculture with a focus on influences of the moon, planets, non-physical beings and elemental forces. They were held in response to a request by adherent farmers who noticed degraded soil conditions and a deterioration in the health and quality of crops and livestock resulting from the use of chemical fertilizers. The lectures were published in November 1924; the first English translation appeared in 1928 as The Agriculture Course.

In July 1939, Ehrenfried Pfeiffer, the author of the standard work on biodynamic agriculture (Bio-Dynamic Farming and Gardening), came to the UK at the invitation of Walter James, 4th Baron Northbourne as a presenter at the Betteshanger Summer School and Conference on Biodynamic Farming at Northbourne's farm in Kent. One of the chief purposes of the conference was to bring together the proponents of various approaches to organic agriculture in order that they might cooperate within a larger movement. Howard attended the conference, where he met Pfeiffer. In the following year, Northbourne published his manifesto of organic farming, Look to the Land, in which he coined the term "organic farming." The Betteshanger conference has been described as the 'missing link' between biodynamic agriculture and other forms of organic farming.

In 1940 Howard published his An Agricultural Testament. In this book he adopted Northbourne's terminology of "organic farming." Howard's work spread widely, and he became known as the "father of organic farming" for his work in applying scientific knowledge and principles to various traditional and natural methods. In the United States J.I. Rodale, who was keenly interested both in Howard's ideas and in biodynamics, founded in the 1940s both a working organic farm for trials and experimentation, The Rodale Institute, and the Rodale Press to teach and advocate organic methods to the wider public. These became important influences on the spread of organic agriculture. Further work was done by Lady Eve Balfour (the Haughley Experiment) in the United Kingdom, and many others across the world.

The term "eco-agriculture" was coined in 1970 by Charles Walters, founder of Acres Magazine, to describe agriculture which does not use "man-made molecules of toxic rescue chemistry", effectively another name for organic agriculture.

Increasing environmental awareness in the general population in modern times has transformed the originally supply-driven organic movement to a demand-driven one. Premium prices and some government subsidies attracted farmers. In the developing world, many producers farm according to traditional methods that are comparable to organic farming, but not certified, and that may not include the latest scientific advancements in organic agriculture. In other cases, farmers in the developing world have converted to modern organic methods for economic reasons.

Terminology

The use of "organic" popularized by Howard and Rodale refers more narrowly to the use of organic matter derived from plant compost and animal manures to improve the humus content of soils, grounded in the work of early soil scientists who developed what was then called "humus farming." Since the early 1940s the two camps have tended to merge.

Biodynamic agriculturists, on the other hand, used the term "organic" to indicate that a farm should be viewed as a living organism, in the sense of the following quotation:

"An organic farm, properly speaking, is not one that uses certain methods and substances and avoids others; it is a farm whose structure is formed in imitation of the structure of a natural system that has the integrity, the independence and the benign dependence of an organism"

— Wendell Berry, "The Gift of Good Land"

They based their work on Steiner's spiritually-oriented alternative agriculture which includes various esoteric concepts.

Methods

"Organic agriculture is a production system that sustains the health of soils, ecosystems and people. It relies on ecological processes, biodiversity and cycles adapted to local conditions, rather than the use of inputs with adverse effects. Organic agriculture combines tradition, innovation and science to benefit the shared environment and promote fair relationships and a good quality of life for all involved..."

Organic farming methods combine scientific knowledge of ecology and some modern technology with traditional farming practices based on naturally occurring biological processes. Organic farming methods are studied in the field of agroecology. While conventional agriculture uses synthetic pesticides and water-soluble synthetically purified fertilizers, organic farmers are restricted by regulations to using natural pesticides and fertilizers. An example of a natural pesticide is pyrethrin, which is found naturally in the Chrysanthemum flower. The principal methods of organic farming include crop rotation, green manures and compost, biological pest control, and mechanical cultivation. These measures use the natural environment to enhance agricultural productivity: legumes are planted to fix nitrogen into the soil, natural insect predators are encouraged, crops are rotated to confuse pests and renew soil, and natural materials such as potassium bicarbonate and mulches are used to control disease and weeds. Genetically modified seeds and animals are excluded.

While organic is fundamentally different from conventional because of the use of carbon-based fertilizers compared with highly soluble synthetic based fertilizers and biological pest control instead of synthetic pesticides, organic farming and large-scale conventional farming are not entirely mutually exclusive. Many of the methods developed for organic agriculture have been borrowed by more conventional agriculture. For example, Integrated Pest Management is a multifaceted strategy that uses various organic methods of pest control whenever possible, but in conventional farming could include synthetic pesticides only as a last resort.

Crop diversity

Organic farming encourages Crop diversity. The science of agroecology has revealed the benefits of polyculture (multiple crops in the same space), which is often employed in organic farming. Planting a variety of vegetable crops supports a wider range of beneficial insects, soil microorganisms, and other factors that add up to overall farm health. Crop diversity helps environments thrive and protects species from going extinct.

Soil management

Organic farming relies more heavily on the natural breakdown of organic matter then the average conventional farm, using techniques like green manure and composting, to replace nutrients taken from the soil by previous crops. This biological process, driven by microorganisms such as mycorrhiza and earthworms, releases nutrients available to plants throughout the growing season. Farmers use a variety of methods to improve soil fertility, including crop rotation, cover cropping, reduced tillage, and application of compost. By reducing fuel-intensive tillage, less soil organic matter is lost to the atmosphere. This has an added benefit of carbon sequestration, which reduces greenhouse gases and helps reverse climate change. Reducing tillage may also improve soil structure and reduce the potential for soil erosion.

Plants need a large number of nutrients in various quantities to flourish. Supplying enough nitrogen and particularly synchronization, so that plants get enough nitrogen at the time when they need it most, is a challenge for organic farmers. Crop rotation and green manure ("cover crops") help to provide nitrogen through legumes (more precisely, the family Fabaceae), which fix nitrogen from the atmosphere through symbiosis with rhizobial bacteria. Intercropping, which is sometimes used for insect and disease control, can also increase soil nutrients, but the competition between the legume and the crop can be problematic and wider spacing between crop rows is required. Crop residues can be ploughed back into the soil, and different plants leave different amounts of nitrogen, potentially aiding synchronization. Organic farmers also use animal manure, certain processed fertilizers such as seed meal and various mineral powders such as rock phosphate and green sand, a naturally occurring form of potash that provides potassium. In some cases pH may need to be amended. Natural pH amendments include lime and sulfur, but in the U.S. some compounds such as iron sulfate, aluminum sulfate, magnesium sulfate, and soluble boron products are allowed in organic farming.

Mixed farms with both livestock and crops can operate as ley farms, whereby the land gathers fertility through growing nitrogen-fixing forage grasses such as white clover or alfalfa and grows cash crops or cereals when fertility is established. Farms without livestock ("stockless") may find it more difficult to maintain soil fertility, and may rely more on external inputs such as imported manure as well as grain legumes and green manures, although grain legumes may fix limited nitrogen because they are harvested. Horticultural farms that grow fruits and vegetables in protected conditions often rely even more on external inputs. Manure is very bulky and is often not cost-effective to transport more than a short distance from the source. Manure for organic farms' may become scarce if a sizable number of farms become organically managed.

Weed management

Organic weed management promotes weed suppression, rather than weed elimination, by enhancing crop competition and phytotoxic effects on weeds. Organic farmers integrate cultural, biological, mechanical, physical and chemical tactics to manage weeds without synthetic herbicides.

Organic standards require rotation of annual crops, meaning that a single crop cannot be grown in the same location without a different, intervening crop. Organic crop rotations frequently include weed-suppressive cover crops and crops with dissimilar life cycles to discourage weeds associated with a particular crop. Research is ongoing to develop organic methods to promote the growth of natural microorganisms that suppress the growth or germination of common weeds.

Other cultural practices used to enhance crop competitiveness and reduce weed pressure include selection of competitive crop varieties, high-density planting, tight row spacing, and late planting into warm soil to encourage rapid crop germination.

Mechanical and physical weed control practices used on organic farms can be broadly grouped as:

- Tillage - Turning the soil between crops to incorporate crop residues and soil amendments; remove existing weed growth and prepare a seedbed for planting; turning soil after seeding to kill weeds, including cultivation of row crops;

- Mowing and cutting - Removing top growth of weeds;

- Flame weeding and thermal weeding - Using heat to kill weeds; and

- Mulching - Blocking weed emergence with organic materials, plastic films, or landscape fabric. Some critics, citing work published in 1997 by David Pimentel of Cornell University, which described an epidemic of soil erosion worldwide, have raised concerned that tillage contribute to the erosion epidemic. The FAO and other organizations have advocated a 'no-till' approach to both conventional and organic farming, and point out in particular that crop rotation techniques used in organic farming are excellent no-till approaches. A study published in 2005 by Pimentel and colleagues confirmed that 'Crop rotations and cover cropping (green manure) typical of organic agriculture reduce soil erosion, pest problems, and pesticide use.'

Some naturally sourced chemicals are allowed for herbicidal use. These include certain formulations of acetic acid (concentrated vinegar), corn gluten meal, and essential oils. A few selective bioherbicides based on fungal pathogens have also been developed. At this time, however, organic herbicides and bioherbicides play a minor role in the organic weed control toolbox.

Weeds can be controlled by grazing. For example, geese have been used successfully to weed a range of organic crops including cotton, strawberries, tobacco, and corn, reviving the practice of keeping cotton patch geese, common in the southern U.S. before the 1950s. Similarly, some rice farmers introduce ducks and fish to wet paddy fields to eat both weeds and insects.

Controlling other organisms

Organisms aside from weeds that cause problems on farms include arthropods (e.g., insects, mites), nematodes, fungi and bacteria. Practices include, but are not limited to:

- encouraging predatory beneficial insects to control pests by serving them nursery plants and/or an alternative habitat, usually in a form of a shelterbelt, hedgerow, or beetle bank;

- encouraging beneficial microorganisms;

- rotating crops to different locations from year to year to interrupt pest reproduction cycles;

- planting companion crops and pest-repelling plants that discourage or divert pests;

- using row covers to protect crops during pest migration periods;

- using biologic pesticides and herbicides;

- using stale seed beds to germinate and destroy weeds before planting;

- using sanitation to remove pest habitat;

- using insect traps to monitor and control insect populations; and

- using physical barriers, such as row covers.

Examples of predatory beneficial insects include minute pirate bugs, big-eyed bugs, and to a lesser extent ladybugs (which tend to fly away), all of which eat a wide range of pests. Lacewings are also effective, but tend to fly away. Praying mantis tend to move more slowly and eat less heavily. Parasitoid wasps tend to be effective for their selected prey, but like all small insects can be less effective outdoors because the wind controls their movement. Predatory mites are effective for controlling other mites.

Naturally derived insecticides allowed for use on organic farms use include Bacillus thuringiensis (a bacterial toxin), pyrethrum (a chrysanthemum extract), spinosad (a bacterial metabolite), neem (a tree extract) and rotenone (a legume root extract). Fewer than 10% of organic farmers use these pesticides regularly; one survey found that only 5.3% of vegetable growers in California use rotenone while 1.7% use pyrethrum. These pesticides are not always more safe or environmentally friendly than synthetic pesticides and can cause harm. The main criterion for organic pesticides is that they are naturally derived, and some naturally derived substances have been controversial. Controversial natural pesticides include rotenone, copper, nicotine sulfate, and pyrethrums Rotenone and pyrethrum are particularly controversial because they work by attacking the nervous system, like most conventional insecticides. Rotenone is extremely toxic to fish and can induce symptoms resembling Parkinson's disease in mammals. Although pyrethrum (natural pyrethrins) is more effective against insects when used with piperonyl butoxide (which retards degradation of the pyrethrins), organic standards generally do not permit use of the latter substance.

Naturally derived fungicides allowed for use on organic farms include the bacteria Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus pumilus; and the fungus Trichoderma harzianum. These are mainly effective for diseases affecting roots. Compost tea contains a mix of beneficial microbes, which may attack or out-compete certain plant pathogens, but variability among formulations and preparation methods may contribute to inconsistent results or even dangerous growth of toxic microbes in compost teas.

Some naturally derived pesticides are not allowed for use on organic farms. These include nicotine sulfate, arsenic, and strychnine.

Synthetic pesticides allowed for use on organic farms include insecticidal soaps and horticultural oils for insect management; and Bordeaux mixture, copper hydroxide and sodium bicarbonate for managing fungi. Copper sulfate and Bordeaux mixture (copper sulfate plus lime), approved for organic use in various jurisdictions, can be more environmentally problematic than some synthetic fungicides dissallowed in organic farming. Similar concerns apply to copper hydroxide. Repeated application of copper sulfate or copper hydroxide as a fungicide may eventually result in copper accumulation to toxic levels in soil, and admonitions to avoid excessive accumulations of copper in soil appear in various organic standards and elsewhere. Environmental concerns for several kinds of biota arise at average rates of use of such substances for some crops. In the European Union, where replacement of copper-based fungicides in organic agriculture is a policy priority, research is seeking alternatives for organic production.

Livestock

Raising livestock and poultry, for meat, dairy and eggs, is another traditional farming activity that complements growing. Organic farms attempt to provide animals with natural living conditions and feed. Organic certification verifies that livestock are raised according to the USDA organic regulations throughout their lives. These regulations include the requirement that all animal feed must be certified organic.

Organic livestock may be, and must be, treated with medicine when they are sick, but drugs cannot be used to promote growth, their feed must be organic, and they must be pastured.

Also, horses and cattle were once a basic farm feature that provided labour, for hauling and plowing, fertility, through recycling of manure, and fuel, in the form of food for farmers and other animals. While today, small growing operations often do not include livestock, domesticated animals are a desirable part of the organic farming equation, especially for true sustainability, the ability of a farm to function as a self-renewing unit.

Genetic modification

A key characteristic of organic farming is the exclusion of genetically engineered plants and animals. On 19 October 1998, participants at IFOAM's 12th Scientific Conference issued the Mar del Plata Declaration, where more than 600 delegates from over 60 countries voted unanimously to exclude the use of genetically modified organisms in organic food production and agriculture.

Although opposition to the use of any transgenic technologies in organic farming is strong, agricultural researchers Luis Herrera-Estrella and Ariel Alvarez-Morales continue to advocate integration of transgenic technologies into organic farming as the optimal means to sustainable agriculture, particularly in the developing world. Organic farmer Raoul Adamchak and geneticist Pamela Ronald write that many agricultural applications of biotechnology are consistent with organic principles and have significantly advanced sustainable agriculture.

Although GMOs are excluded from organic farming, there is concern that the pollen from genetically modified crops is increasingly penetrating organic and heirloom seed stocks, making it difficult, if not impossible, to keep these genomes from entering the organic food supply. Differing regulations among countries limits the availability of GMOs to certain countries, as described in the article on regulation of the release of genetic modified organisms.

Tools

Organic farmers use a number of traditional farm tools to do farming. Due to the goals of sustainability in organic farming, organic farmers try to minimize their reliance on fossil fuels. In the developing world on small organic farms tools are normally constrained to hand tools and diesel powered water pumps.

Standards

Standards regulate production methods and in some cases final output for organic agriculture. Standards may be voluntary or legislated. As early as the 1970s private associations certified organic producers. In the 1980s, governments began to produce organic production guidelines. In the 1990s, a trend toward legislated standards began, most notably with the 1991 EU-Eco-regulation developed for European Union, which set standards for 12 countries, and a 1993 UK program. The EU's program was followed by a Japanese program in 2001, and in 2002 the U.S. created the National Organic Program (NOP). As of 2007 over 60 countries regulate organic farming (IFOAM 2007:11). In 2005 IFOAM created the Principles of Organic Agriculture, an international guideline for certification criteria. Typically the agencies accredit certification groups rather than individual farms.

Production materials used for the creation of USDA Organic certified foods require the approval of a NOP accredited certifier.

Composting

Using manure as a fertilizer risks contaminating food with animal gut bacteria, including pathogenic strains of E. coli that have caused fatal poisoning from eating organic food. To combat this risk, USDA organic standards require that manure must be sterilized through high temperature thermophilic composting. If raw animal manure is used, 120 days must pass before the crop is harvested if the final product comes into direct contact with the soil. For products that don't directly contact soil, 90 days must pass prior to harvest.

In the US, the Organic Food Production Act of 1990 (OFPA,) as amended, specifies that a farm can not be certified as organic if the compost being used contains any synthetic ingredients. The OFPA singles out commercially blended fertilizers [composts] disallowing the use of any fertilizer [compost] that contains prohibited materials.

Economics

The economics of organic farming, a subfield of agricultural economics, encompasses the entire process and effects of organic farming in terms of human society, including social costs, opportunity costs, unintended consequences, information asymmetries, and economies of scale. Although the scope of economics is broad, agricultural economics tends to focus on maximizing yields and efficiency at the farm level. Economics takes an anthropocentric approach to the value of the natural world: biodiversity, for example, is considered beneficial only to the extent that it is valued by people and increases profits. Some entities such as the European Union subsidize organic farming, in large part because these countries want to account for the externalities of reduced water use, reduced water contamination, reduced soil erosion, reduced carbon emissions, increased biodiversity, and assorted other benefits that result from organic farming.

Traditional organic farming is labour and knowledge-intensive.

Organic farmers in California have cited marketing as their greatest obstacle.

Geographic producer distribution

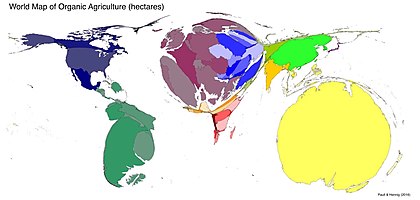

The markets for organic products are strongest in North America and Europe, which as of 2001 are estimated to have $6 and $8 billion respectively of the $20 billion global market. As of 2007 Australasia has 39% of the total organic farmland, including Australia's 11,800,000 hectares (29,000,000 acres) but 97 percent of this land is sprawling rangeland (2007:35). US sales are 20x as much. Europe farms 23 percent of global organic farmland (6,900,000 ha (17,000,000 acres)), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean with 20 percent (6,400,000 ha (16,000,000 acres)). Asia has 9.5 percent while North America has 7.2 percent. Africa has 3 percent.

Besides Australia, the countries with the most organic farmland are Argentina (3.1 million hectares - 7.7 million acres), China (2.3 million hectares - 5.7 million acres), and the United States (1.6 million hectares - 4 million acres). Much of Argentina's organic farmland is pasture, like that of Australia (2007:42). Spain, Germany, Brazil (the world's largest agricultural exporter), Uruguay, and England follow the United States in the amount of organic land (2007:26).

In the European Union (EU25) 3.9% of the total utilized agricultural area was used for organic production in 2005. The countries with the highest proportion of organic land were Austria (11%) and Italy (8.4%), followed by the Czech Republic and Greece (both 7.2%). The lowest figures were shown for Malta (0.2%), Poland (0.6%) and Ireland (0.8%). In 2009, the proportion of organic land in the EU grew to 4.7%. The countries with the highest share of agricultural land were Liechtenstein (26.9%), Austria (18.5%) and Sweden (12.6%). 16% of all farmers in Austria produced organically in 2010. By the same year the proportion of organic land increased to 20%. In 2005 168,000 ha (415,000 ac) of land in Poland was under organic management. In 2012, 288,261 hectares (712,308 acres) were under organic production, and there were about 15,500 organic farmers; retail sales of organic products were EUR 80 million in 2011. As of 2012 organic exports were part of the government's economic development strategy.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, agricultural inputs that had previously been purchased from Eastern bloc countries were no longer available in Cuba, and many Cuban farms converted to organic methods out of necessity. Consequently, organic agriculture is a mainstream practice in Cuba, while it remains an alternative practice in most other countries. Cuba's organic strategy includes development of genetically modified crops; specifically corn that is resistant to the palomilla moth.

Growth

In 2001, the global market value of certified organic products was estimated at US$20 billion. By 2002, this was US$23 billion and by 2015 more than US$43 billion. By 2014, retail sales of organic products reached US$80 billion worldwide. North America and Europe accounted for more than 90% of all organic product sales. In 2018 Australia accounted for 54% of the world's certified organic land with the country recording more than 35,000,000 verified organic hectares.

Organic agricultural land increased almost fourfold in 15 years, from 11 million hectares in 1999 to 43.7 million hectares in 2014. Between 2013 and 2014, organic agricultural land grew by 500,000 hectares worldwide, increasing in every region except Latin America. During this time period, Europe's organic farmland increased 260,000 hectares to 11.6 million total (+2.3%), Asia's increased 159,000 hectares to 3.6 million total (+4.7%), Africa's increased 54,000 hectares to 1.3 million total (+4.5%), and North America's increased 35,000 hectares to 3.1 million total (+1.1%). As of 2014, the country with the most organic land was Australia (17.2 million hectares), followed by Argentina (3.1 million hectares), and the United States (2.2 million hectares). Australia's organic land area has increased at a rate of 16.5% per annum for the past eighteen years.

In 2013, the number of organic producers grew by almost 270,000, or more than 13%. By 2014, there were a reported 2.3 million organic producers in the world. Most of the total global increase took place in the Philippines, Peru, China, and Thailand. Overall, the majority of all organic producers are in India (650,000 in 2013), Uganda (190,552 in 2014), Mexico (169,703 in 2013) and the Philippines (165,974 in 2014).

In 2016, organic farming was responsible for producing over 1 million metric tonnes of bananas, over 800,000 metric tonnes of soybean, and just under half a million metric tonnes of coffee.

Productivity

Studies comparing yields have had mixed results. These differences among findings can often be attributed to variations between study designs including differences in the crops studied and the methodology by which results were gathered.

A 2012 meta-analysis found that productivity is typically lower for organic farming than conventional farming, but that the size of the difference depends on context and in some cases may be very small. While organic yields can be lower than conventional yields, another meta-analysis published in Sustainable Agriculture Research in 2015, concluded that certain organic on-farm practices could help narrow this gap. Timely weed management and the application of manure in conjunction with legume forages/cover crops were shown to have positive results in increasing organic corn and soybean productivity.

Another meta-analysis published in the journal Agricultural Systems in 2011 analysed 362 datasets and found that organic yields were on average 80% of conventional yields. The author's found that there are relative differences in this yield gap based on crop type with crops like soybeans and rice scoring higher than the 80% average and crops like wheat and potato scoring lower. Across global regions, Asia and Central Europe were found to have relatively higher yields and Northern Europe relatively lower than the average.

Long term studies

A study published in 2005 compared conventional cropping, organic animal-based cropping, and organic legume-based cropping on a test farm at the Rodale Institute over 22 years. The study found that "the crop yields for corn and soybeans were similar in the organic animal, organic legume, and conventional farming systems". It also found that "significantly less fossil energy was expended to produce corn in the Rodale Institute’s organic animal and organic legume systems than in the conventional production system. There was little difference in energy input between the different treatments for producing soybeans. In the organic systems, synthetic fertilizers and pesticides were generally not used". As of 2013 the Rodale study was ongoing and a thirty-year anniversary report was published by Rodale in 2012.

A long-term field study comparing organic/conventional agriculture carried out over 21 years in Switzerland concluded that "Crop yields of the organic systems averaged over 21 experimental years at 80% of the conventional ones. The fertilizer input, however, was 34 – 51% lower, indicating an efficient production. The organic farming systems used 20 – 56% less energy to produce a crop unit and per land area this difference was 36 – 53%. In spite of the considerably lower pesticide input the quality of organic products was hardly discernible from conventional analytically and even came off better in food preference trials and picture creating methods"

Profitability

In the United States, organic farming has been shown to be 2.7 to 3.8 times more profitable for the farmer than conventional farming when prevailing price premiums are taken into account. Globally, organic farming is between 22 and 35 percent more profitable for farmers than conventional methods, according to a 2015 meta-analysis of studies conducted across five continents.

The profitability of organic agriculture can be attributed to a number of factors. First, organic farmers do not rely on synthetic fertilizer and pesticide inputs, which can be costly. In addition, organic foods currently enjoy a price premium over conventionally produced foods, meaning that organic farmers can often get more for their yield.

The price premium for organic food is an important factor in the economic viability of organic farming. In 2013 there was a 100% price premium on organic vegetables and a 57% price premium for organic fruits. These percentages are based on wholesale fruit and vegetable prices, available through the United States Department of Agriculture's Economic Research Service. Price premiums exist not only for organic versus nonorganic crops, but may also vary depending on the venue where the product is sold: farmers' markets, grocery stores, or wholesale to restaurants. For many producers, direct sales at farmers' markets are most profitable because the farmer receives the entire markup, however this is also the most time and labour-intensive approach.

There have been signs of organic price premiums narrowing in recent years, which lowers the economic incentive for farmers to convert to or maintain organic production methods. Data from 22 years of experiments at the Rodale Institute found that, based on the current yields and production costs associated with organic farming in the United States, a price premium of only 10% is required to achieve parity with conventional farming. A separate study found that on a global scale, price premiums of only 5-7% percent were needed to break even with conventional methods. Without the price premium, profitability for farmers is mixed.

For markets and supermarkets organic food is profitable as well, and is generally sold at significantly higher prices than non-organic food.

Energy efficiency

In the most recent assessments of the energy efficiency of organic versus conventional agriculture, results have been mixed regarding which form is more carbon efficient. Organic farm systems have more often than not been found to be more energy efficient, however, this is not always the case. More than anything, results tend to depend upon crop type and farm size.

A comprehensive comparison of energy efficiency in grain production, produce yield, and animal husbandry concluded that organic farming had a higher yield per unit of energy over the vast majority of the crops and livestock systems. For example, two studies – both comparing organically- versus conventionally-farmed apples – declare contradicting results, one saying organic farming is more energy efficient, the other saying conventionally is more efficient.

It has generally been found that the labour input per unit of yield was higher for organic systems compared with conventional production.

Sales and marketing

Most sales are concentrated in developed nations. In 2008, 69% of Americans claimed to occasionally buy organic products, down from 73% in 2005. One theory for this change was that consumers were substituting "local" produce for "organic" produce.

Distributors

The USDA requires that distributors, manufacturers, and processors of organic products be certified by an accredited state or private agency. In 2007, there were 3,225 certified organic handlers, up from 2,790 in 2004.

Organic handlers are often small firms; 48% reported sales below $1 million annually, and 22% between $1 and $5 million per year. Smaller handlers are more likely to sell to independent natural grocery stores and natural product chains whereas large distributors more often market to natural product chains and conventional supermarkets, with a small group marketing to independent natural product stores. Some handlers work with conventional farmers to convert their land to organic with the knowledge that the farmer will have a secure sales outlet. This lowers the risk for the handler as well as the farmer. In 2004, 31% of handlers provided technical support on organic standards or production to their suppliers and 34% encouraged their suppliers to transition to organic. Smaller farms often join together in cooperatives to market their goods more effectively.

93% of organic sales are through conventional and natural food supermarkets and chains, while the remaining 7% of U.S. organic food sales occur through farmers' markets, foodservices, and other marketing channels.

Direct-to-consumer sales

In the 2012 Census, direct-to-consumer sales equalled $1.3 billion, up from $812 million in 2002, an increase of 60 percent. The number of farms that utilize direct-to-consumer sales was 144,530 in 2012 in comparison to 116,733 in 2002. Direct-to-consumer sales include farmers' markets, community supported agriculture (CSA), on-farm stores, and roadside farm stands. Some organic farms also sell products direct to retailer, direct to restaurant and direct to institution. According to the 2008 Organic Production Survey, approximately 7% of organic farm sales were direct-to-consumers, 10% went direct to retailers, and approximately 83% went into wholesale markets. In comparison, only 0.4% of the value of convention agricultural commodities were direct-to-consumers.

While not all products sold at farmer's markets are certified organic, this direct-to-consumer avenue has become increasingly popular in local food distribution and has grown substantially since 1994. In 2014, there were 8,284 farmer's markets in comparison to 3,706 in 2004 and 1,755 in 1994, most of which are found in populated areas such as the Northeast, Midwest, and West Coast.

Labour and employment

Organic production is more labour-intensive than conventional production. On the one hand, this increased labour cost is one factor that makes organic food more expensive. On the other hand, the increased need for labour may be seen as an "employment dividend" of organic farming, providing more jobs per unit area than conventional systems. The 2011 UNEP Green Economy Report suggests that "[a]n increase in investment in green agriculture is projected to lead to growth in employment of about 60 per cent compared with current levels" and that "green agriculture investments could create 47 million additional jobs compared with BAU2 over the next 40 years." The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) also argues that "[b]y greening agriculture and food distribution, more calories per person per day, more jobs and business opportunities especially in rural areas, and market-access opportunities, especially for developing countries, will be available."

Much of the growth in women labour participation in agriculture is outside the "male dominated field of conventional agriculture". Operators in organic farming are 21% women, as opposed to 14% in farming in general.

World's food security

In 2007 the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) said that organic agriculture often leads to higher prices and hence a better income for farmers, so it should be promoted. However, FAO stressed that by organic farming one could not feed the current mankind, even less the bigger future population. Both data and models showed then that organic farming was far from sufficient. Therefore, chemical fertilizers were needed to avoid hunger. Other analysis by many agribusiness executives, agricultural and environmental scientists, and international agriculture experts revealed the opinion that organic farming would not only increase the world's food supply, but might be the only way to eradicate hunger.

FAO stressed that fertilizers and other chemical inputs can much increase the production, particularly in Africa where fertilizers are currently used 90% less than in Asia. For example, in Malawi the yield has been boosted using seeds and fertilizers. FAO also calls for using biotechnology, as it can help smallholder farmers to improve their income and food security.

Also NEPAD, development organization of African governments, announced that feeding Africans and preventing malnutrition requires fertilizers and enhanced seeds.

According to a 2012 study in ScienceDigest, organic best management practices shows an average yield only 13% less than conventional. In the world's poorer nations where most of the world's hungry live, and where conventional agriculture's expensive inputs are not affordable by the majority of farmers, adopting organic management actually increases yields 93% on average, and could be an important part of increased food security.

Capacity building in developing countries

Organic agriculture can contribute to ecological sustainability, especially in poorer countries. The application of organic principles enables employment of local resources (e.g., local seed varieties, manure, etc.) and therefore cost-effectiveness. Local and international markets for organic products show tremendous growth prospects and offer creative producers and exporters excellent opportunities to improve their income and living conditions.

Organic agriculture is knowledge intensive. Globally, capacity building efforts are underway, including localized training material, to limited effect. As of 2007, the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements hosted more than 170 free manuals and 75 training opportunities online.

In 2008 the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) stated that "organic agriculture can be more conducive to food security in Africa than most conventional production systems, and that it is more likely to be sustainable in the long-term" and that "yields had more than doubled where organic, or near-organic practices had been used" and that soil fertility and drought resistance improved.

Millennium Development Goals

The value of organic agriculture (OA) in the achievement of the Millennium Development Goals (MDG), particularly in poverty reduction efforts in the face of climate change, is shown by its contribution to both income and non-income aspects of the MDGs. These benefits are expected to continue in the post-MDG era. A series of case studies conducted in selected areas in Asian countries by the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI) and published as a book compilation by ADB in Manila document these contributions to both income and non-income aspects of the MDGs. These include poverty alleviation by way of higher incomes, improved farmers' health owing to less chemical exposure, integration of sustainable principles into rural development policies, improvement of access to safe water and sanitation, and expansion of global partnership for development as small farmers are integrated in value chains.

A related ADBI study also sheds on the costs of OA programs and set them in the context of the costs of attaining the MDGs. The results show considerable variation across the case studies, suggesting that there is no clear structure to the costs of adopting OA. Costs depend on the efficiency of the OA adoption programs. The lowest cost programs were more than ten times less expensive than the highest cost ones. However, further analysis of the gains resulting from OA adoption reveals that the costs per person taken out of poverty was much lower than the estimates of the World Bank, based on income growth in general or based on the detailed costs of meeting some of the more quantifiable MDGs (e.g., education, health, and environment).

Externalities

Agriculture imposes negative externalities (uncompensated costs) upon society through public land and other public resource use, biodiversity loss, erosion, pesticides, nutrient runoff, subsidized water usage, subsidy payments and assorted other problems. Positive externalities include self-reliance, entrepreneurship, respect for nature, and air quality. Organic methods reduce some of these costs. In 2000 uncompensated costs for 1996 reached 2,343 million British pounds or £208 per ha (£84.20/ac). A study of practices in the US published in 2005 concluded that cropland costs the economy approximately 5 to 16 billion dollars ($30–96/ha – $12–39/ac), while livestock production costs 714 million dollars. Both studies recommended reducing externalities. The 2000 review included reported pesticide poisonings but did not include speculative chronic health effects of pesticides, and the 2004 review relied on a 1992 estimate of the total impact of pesticides.

It has been proposed that organic agriculture can reduce the level of some negative externalities from (conventional) agriculture. Whether the benefits are private or public depends upon the division of property rights.

Several surveys and studies have attempted to examine and compare conventional and organic systems of farming and have found that organic techniques, while not without harm, are less damaging than conventional ones because they reduce levels of biodiversity less than conventional systems do and use less energy and produce less waste when calculated per unit area.

Issues

A 2003 to 2005 investigation by the Cranfield University for the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs in the UK found that it is difficult to compare the Global warming potential, acidification and eutrophication emissions but "Organic production often results in increased burdens, from factors such as N leaching and N2O emissions", even though primary energy use was less for most organic products. N2O is always the largest global warming potential contributor except in tomatoes. However, "organic tomatoes always incur more burdens (except pesticide use)". Some emissions were lower "per area", but organic farming always required 65 to 200% more field area than non-organic farming. The numbers were highest for bread wheat (200+ % more) and potatoes (160% more).

As of 2020 it seems that organic agriculture can help in mitigating climate change but only if used in certain ways.

Environmental impact and emissions

Researchers at Oxford University analysed 71 peer-reviewed studies and observed that organic products are sometimes worse for the environment. Organic milk, cereals, and pork generated higher greenhouse gas emissions per product than conventional ones but organic beef and olives had lower emissions in most studies. Usually organic products required less energy, but more land. Per unit of product, organic produce generates higher nitrogen leaching, nitrous oxide emissions, ammonia emissions, eutrophication, and acidification potential than conventionally grown produce. Other differences were not significant. The researchers concluded that public debate should consider various manners of employing conventional or organic farming, and not merely debate conventional farming as opposed to organic farming. They also sought to find specific solutions to specific circumstances.

Proponents of organic farming have claimed that organic agriculture emphasizes closed nutrient cycles, biodiversity, and effective soil management providing the capacity to mitigate and even reverse the effects of climate change and that organic agriculture can decrease fossil fuel emissions. "The carbon sequestration efficiency of organic systems in temperate climates is almost double (575–700 kg carbon per ha per year – 510–625 lb/ac/an ) that of conventional treatment of soils, mainly owing to the use of grass clovers for feed and of cover crops in organic rotations."

Critics of organic farming methods believe that the increased land needed to farm organic food could potentially destroy the rainforests and wipe out many ecosystems.

Nutrient leaching

According to a 2012 meta-analysis of 71 studies, nitrogen leaching, nitrous oxide emissions, ammonia emissions, eutrophication potential and acidification potential were higher for organic products, although in one study "nitrate leaching was 4.4–5.6 times higher in conventional plots than organic plots". Excess nutrients in lakes, rivers, and groundwater can cause algal blooms, eutrophication, and subsequent dead zones. In addition, nitrates are harmful to aquatic organisms by themselves.

Land use

The Oxford meta-analysis of 71 studies found that organic farming requires 84% more land for an equivalent amount of harvest, mainly due to lack of nutrients but sometimes due to weeds, diseases or pests, lower yielding animals and land required for fertility building crops. While organic farming does not necessarily save land for wildlife habitats and forestry in all cases, the most modern breakthroughs in organic are addressing these issues with success.

Professor Wolfgang Branscheid says that organic animal production is not good for the environment, because organic chicken requires twice as much land as "conventional" chicken and organic pork a quarter more. According to a calculation by Hudson Institute, organic beef requires three times as much land. On the other hand, certain organic methods of animal husbandry have been shown to restore desertified, marginal, and/or otherwise unavailable land to agricultural productivity and wildlife. Or by getting both forage and cash crop production from the same fields simultaneously, reduce net land use.

In some regions of the world, organic methods have started producing record yields.

Pesticides

In organic farming synthetic pesticides are generally prohibited. A chemical is said to be synthetic if it does not already exist in the natural world. But the organic label goes further and usually prohibit compounds that exist in nature if they are produced by chemical synthesis. So the prohibition is also about the method of production and not only the nature of the compound.

A non-exhaustive list of organic approved pesticides with their median lethal doses:

- Boric acid is used as an insecticide (LD50: 2660 mg/kg).

- Bromomethane is a gas that is still used in the nurseries of strawberry organic farming

- Copper(II) sulfate is used as a fungicide and is also used in conventional agriculture (LD50 300 mg/kg). Conventional agriculture has the option to use the less toxic Mancozeb (LD50 4,500 to 11,200 mg/kg)

- Lime sulfur (aka calcium polysulfide) and sulfur are considered to be allowed, synthetic materials (LD50: 820 mg/kg)

- Neem oil is used as an insect repellant in India; since it contains azadirachtin its use is restricted in the UK and Europe.

- Pyrethrin comes from chemicals extracted from flowers of the genus Pyrethrum (LD50 of 370 mg/kg). Its potent toxicity is used to control insects.

- Rotenone is a powerful insecticide that was used to control insects (LD50: 132 mg/kg). Despite the high toxicity of Rotenone to aquatic life and some links to Parkinson disease the compound is still allowed in organic farming as it is a naturally occurring compound.

Food quality and safety

While there may be some differences in the amounts of nutrients and anti-nutrients when organically produced food and conventionally produced food are compared, the variable nature of food production and handling makes it difficult to generalize results, and there is insufficient evidence to make claims that organic food is safer or healthier than conventional food. Claims that organic food tastes better are not supported by evidence.

Soil conservation

Supporters claim that organically managed soil has a higher quality and higher water retention. This may help increase yields for organic farms in drought years. Organic farming can build up soil organic matter better than conventional no-till farming, which suggests long-term yield benefits from organic farming. An 18-year study of organic methods on nutrient-depleted soil concluded that conventional methods were superior for soil fertility and yield for nutrient-depleted soils in cold-temperate climates, arguing that much of the benefit from organic farming derives from imported materials that could not be regarded as self-sustaining.

In Dirt: The Erosion of Civilizations, geomorphologist David Montgomery outlines a coming crisis from soil erosion. Agriculture relies on roughly one meter of topsoil, and that is being depleted ten times faster than it is being replaced. No-till farming, which some claim depends upon pesticides, is one way to minimize erosion. However, a 2007 study by the USDA's Agricultural Research Service has found that manure applications in tilled organic farming are better at building up the soil than no-till.

Biodiversity

The conservation of natural resources and biodiversity is a core principle of organic production. Three broad management practices (prohibition/reduced use of chemical pesticides and inorganic fertilizers; sympathetic management of non-cropped habitats; and preservation of mixed farming) that are largely intrinsic (but not exclusive) to organic farming are particularly beneficial for farmland wildlife. Using practices that attract or introduce beneficial insects, provide habitat for birds and mammals, and provide conditions that increase soil biotic diversity serve to supply vital ecological services to organic production systems. Advantages to certified organic operations that implement these types of production practices include: 1) decreased dependence on outside fertility inputs; 2) reduced pest-management costs; 3) more reliable sources of clean water; and 4) better pollination.

Nearly all non-crop, naturally occurring species observed in comparative farm land practice studies show a preference for organic farming both by abundance and diversity. An average of 30% more species inhabit organic farms. Birds, butterflies, soil microbes, beetles, earthworms, spiders, vegetation, and mammals are particularly affected. Lack of herbicides and pesticides improve biodiversity fitness and population density. Many weed species attract beneficial insects that improve soil qualities and forage on weed pests. Soil-bound organisms often benefit because of increased bacteria populations due to natural fertilizer such as manure, while experiencing reduced intake of herbicides and pesticides. Increased biodiversity, especially from beneficial soil microbes and mycorrhizae have been proposed as an explanation for the high yields experienced by some organic plots, especially in light of the differences seen in a 21-year comparison of organic and control fields.

Biodiversity from organic farming provides capital to humans. Species found in organic farms enhance sustainability by reducing human input (e.g., fertilizers, pesticides).

The USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service (AMS) published a Federal Register notice on 15 January 2016, announcing the National Organic Program (NOP) final guidance on Natural Resources and Biodiversity Conservation for Certified Organic Operations. Given the broad scope of natural resources which includes soil, water, wetland, woodland and wildlife, the guidance provides examples of practices that support the underlying conservation principles and demonstrate compliance with USDA organic regulations § 205.200. The final guidance provides organic certifiers and farms with examples of production practices that support conservation principles and comply with the USDA organic regulations, which require operations to maintain or improve natural resources. The final guidance also clarifies the role of certified operations (to submit an OSP to a certifier), certifiers (ensure that the OSP describes or lists practices that explain the operator's monitoring plan and practices to support natural resources and biodiversity conservation), and inspectors (onsite inspection) in the implementation and verification of these production practices.

A wide range of organisms benefit from organic farming, but it is unclear whether organic methods confer greater benefits than conventional integrated agri-environmental programs. Organic farming is often presented as a more biodiversity-friendly practice, but the generality of the beneficial effects of organic farming is debated as the effects appear often species- and context-dependent, and current research has highlighted the need to quantify the relative effects of local- and landscape-scale management on farmland biodiversity. There are four key issues when comparing the impacts on biodiversity of organic and conventional farming: (1) It remains unclear whether a holistic whole-farm approach (i.e. organic) provides greater benefits to biodiversity than carefully targeted prescriptions applied to relatively small areas of cropped and/or non-cropped habitats within conventional agriculture (i.e. agri-environment schemes); (2) Many comparative studies encounter methodological problems, limiting their ability to draw quantitative conclusions; (3) Our knowledge of the impacts of organic farming in pastoral and upland agriculture is limited; (4) There remains a pressing need for longitudinal, system-level studies in order to address these issues and to fill in the gaps in our knowledge of the impacts of organic farming, before a full appraisal of its potential role in biodiversity conservation in agroecosystems can be made.

Opposition to labour standards

Organic agriculture is often considered to be more socially just and economically sustainable for farmworkers than conventional agriculture. However, there is little social science research or consensus as to whether or not organic agriculture provides better working conditions than conventional agriculture. As many consumers equate organic and sustainable agriculture with small-scale, family-owned organizations it is widely interpreted that buying organic supports better conditions for farmworkers than buying with conventional producers. Organic agriculture is generally more labour-intensive due to its dependence on manual practices for fertilization and pest removal and relies heavily upon hired, non-family farmworkers rather than family members. Although illnesses from synthetic inputs pose less of a risk, hired workers still fall victim to debilitating musculoskeletal disorders associated with agricultural work. The USDA certification requirements outline growing practices and ecological standards but do nothing to codify labour practices. Independent certification initiatives such as the Agricultural Justice Project, Domestic Fair Trade Working Group, and the Food Alliance have attempted to implement farmworker interests but because these initiatives require voluntary participation of organic farms, their standards cannot be widely enforced. Despite the benefit to farmworkers of implementing labour standards, there is little support among the organic community for these social requirements. Many actors of the organic industry believe that enforcing labour standards would be unnecessary, unacceptable, or unviable due to the constraints of the market.

Regional support for organic farming

China

The Chinese government, especially the local government, has provided various supports for the development of organic agriculture since the 1990s. Organic farming has been recognized by local governments for its potential in promoting sustainable rural development. It is common for local governments to facilitate land access of agribusinesses by negotiating land leasing with local farmers. The government also establishes demonstration organic gardens, provides training for organic food companies to pass certifications, subsidizes organic certification fees, pest repellent lamps, organic fertilizer and so on. The government has also been playing an active role in marketing organic products through organizing organic food expos and branding supports.

India

In India, in 2016, the northern state of Sikkim achieved its goal of converting to 100% organic farming. Other states of India, including Kerala, Mizoram, Goa, Rajasthan, and Meghalaya, have also declared their intentions to shift to fully organic cultivation.

The South Indian state Andhra Pradesh is also promoting organic farming, especially Zero Budget Natural Farming (ZBNF) which is a form of regenerative agriculture.

As of 2018, India has the largest number of organic farmers in the world and constitutes more than 30% of the organic farmers globally. India has 835,000 certified organic producers.

Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic has successfully converted a large amount of its banana crop to organic. The Dominican Republic accounts for 55% of the world's certified organic bananas.

Thailand

In Thailand, the Institute for Sustainable Agricultural Communities (ISAC) was established in 1991 to promote organic farming (among other sustainable agricultural practices). The national target via the National Plan for Organic Farming is to attain, by 2021, 1.3 million rai of organically farmed land. Another target is for 40% of the produce from these farmlands to be consumed domestically.

Much progress has been made:

- Many organic farms have sprouted, growing produce ranging from mangosteen to stinky bean

- Some of the farms have also established education centres to promote and share their organic farming techniques and knowledge

- In Chiang Mai Province, there are 18 organic markets (ISAC-linked)

United States

The United States Department of Agriculture Rural Development (USDARD) was created in 1994 as a subsection of the USDA that implements programs to stimulate growth in rural communities. One of the programs that the USDARD created provided grants to farmers who practiced organic farming through the Organic Certification Cost Share Program (OCCSP). During the 21st century, the United States has continued to expand its reach in the organic foods market, doubling the number of organic farms in the U.S. in 2016 when compared to 2011. Employment on organic farms offers potentially large numbers of jobs for people, and this may better manage the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Moreover, sustainable forestry, fishing, and mining, and other conservation oriented activities provide larger numbers of jobs than more fossil fuel and mechanized work.

- Organic Farming has grown by 3.53 million acres in the U.S. from 2000 to 2011.

- In 2016, California had 2,713 organic farms, which makes California the largest producer of organic goods in the U.S.

- 4 percent of food sales in the U.S. are of organic goods.