| Cell biology | |

|---|---|

| Animal cell diagram | |

Components of a typical animal cell:

|

Ribosomes (/ˈraɪbəzoʊm, -soʊm/) are macromolecular biological machines found within all cells that perform messenger RNA translation. Ribosomes link amino acids together in the order specified by the codons of messenger RNA molecules to form polypeptide chains. Ribosomes consist of two major components: the small and large ribosomal subunits. Each subunit consists of one or more ribosomal RNA molecules and many ribosomal proteins (r-proteins). The ribosomes and associated molecules are also known as the translational apparatus.

Overview

The sequence of DNA that encodes the sequence of the amino acids in a protein is transcribed into a messenger RNA (mRNA) chain. Ribosomes bind to the messenger RNA molecules and use the RNA's sequence of nucleotides to determine the sequence of amino acids needed to generate a protein. Amino acids are selected and carried to the ribosome by transfer RNA (tRNA) molecules, which enter the ribosome and bind to the messenger RNA chain via an anticodon stem loop. For each coding triplet (codon) in the messenger RNA, there is a unique transfer RNA that must have the exact anti-codon match, and carries the correct amino acid for incorporating into a growing polypeptide chain. Once the protein is produced, it can then fold to produce a functional three-dimensional structure.

A ribosome is made from complexes of RNAs and proteins and is therefore a ribonucleoprotein complex. In prokaryotes each ribosome is composed of small (30S) and large (50S) components, called subunits, which are bound to each other:

- (30S) has mainly a decoding function and is also bound to the mRNA

- (50S) has mainly a catalytic function and is also bound to the aminoacylated tRNAs.

The synthesis of proteins from their building blocks takes place in four phases: initiation, elongation, termination, and recycling. The start codon in all mRNA molecules has the sequence AUG. The stop codon is one of UAA, UAG, or UGA; since there are no tRNA molecules that recognize these codons, the ribosome recognizes that translation is complete. When a ribosome finishes reading an mRNA molecule, the two subunits separate and are usually broken up but can be reused. Ribosomes are a kind of enzyme, called ribozymes because the catalytic peptidyl transferase activity that links amino acids together is performed by the ribosomal RNA.

In eukaryotic cells, ribosomes are often associated with the intracellular membranes of the rough endoplasmic reticulum.

Ribosomes from bacteria, archaea, and eukaryotes (in the three-domain system) resemble each other to a remarkable degree, evidence of a common origin. They differ in their size, sequence, structure, and the ratio of protein to RNA. The differences in structure allow some antibiotics to kill bacteria by inhibiting their ribosomes while leaving human ribosomes unaffected. In all domains, a polysome of two or more ribosomes may move along a single mRNA chain at one time, each reading a specific sequence and producing a corresponding protein molecule.

The mitochondrial ribosomes of eukaryotic cells are distinct from the other ribosomes. They functionally resemble those in bacteria, reflecting the evolutionary origin of mitochondria as endosymbiotic bacteria.

Discovery

Ribosomes were first observed in the mid-1950s by Romanian-American cell biologist George Emil Palade, using an electron microscope, as dense particles or granules. They were initially called Palade granules due to their granular structure. The term "ribosome" was proposed in 1958 by Howard M. Dintzis:

During the course of the symposium a semantic difficulty became apparent. To some of the participants, "microsomes" mean the ribonucleoprotein particles of the microsome fraction contaminated by other protein and lipid material; to others, the microsomes consist of protein and lipid contaminated by particles. The phrase "microsomal particles" does not seem adequate, and "ribonucleoprotein particles of the microsome fraction" is much too awkward. During the meeting, the word "ribosome" was suggested, which has a very satisfactory name and a pleasant sound. The present confusion would be eliminated if "ribosome" were adopted to designate ribonucleoprotein particles in sizes ranging from 35 to 100S.

— Albert Claude, Microsomal Particles and Protein Synthesis

Albert Claude, Christian de Duve, and George Emil Palade were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, in 1974, for the discovery of the ribosome. The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 2009 was awarded to Venkatraman Ramakrishnan, Thomas A. Steitz and Ada E. Yonath for determining the detailed structure and mechanism of the ribosome.

Structure

The ribosome is a complex cellular machine. It is largely made up of specialized RNA known as ribosomal RNA (rRNA) as well as dozens of distinct proteins (the exact number varies slightly between species). The ribosomal proteins and rRNAs are arranged into two distinct ribosomal pieces of different sizes, known generally as the large and small subunits of the ribosome. Ribosomes consist of two subunits that fit together and work as one to translate the mRNA into a polypeptide chain during protein synthesis. Because they are formed from two subunits of non-equal size, they are slightly longer on the axis than in diameter.

Prokaryotic ribosomes

Prokaryotic ribosomes are around 20 nm (200 Å) in diameter and are composed of 65% rRNA and 35% ribosomal proteins. Eukaryotic ribosomes are between 25 and 30 nm (250–300 Å) in diameter with an rRNA-to-protein ratio that is close to 1. Crystallographic work has shown that there are no ribosomal proteins close to the reaction site for polypeptide synthesis. This suggests that the protein components of ribosomes do not directly participate in peptide bond formation catalysis, but rather that these proteins act as a scaffold that may enhance the ability of rRNA to synthesize protein

The ribosomal subunits of prokaryotes and eukaryotes are quite similar.

The unit of measurement used to describe the ribosomal subunits and the rRNA fragments is the Svedberg unit, a measure of the rate of sedimentation in centrifugation rather than size. This accounts for why fragment names do not add up: for example, bacterial 70S ribosomes are made of 50S and 30S subunits.

Prokaryotes have 70S ribosomes, each consisting of a small (30S) and a large (50S) subunit. E. coli, for example, has a 16S RNA subunit (consisting of 1540 nucleotides) that is bound to 21 proteins. The large subunit is composed of a 5S RNA subunit (120 nucleotides), a 23S RNA subunit (2900 nucleotides) and 31 proteins.

Ribosome of E. coli (a bacterium) ribosome subunit rRNAs r-proteins 70S 50S 23S (2904 nt) 31 5S (120 nt) 30S 16S (1542 nt) 21

Affinity label for the tRNA binding sites on the E. coli ribosome allowed the identification of A and P site proteins most likely associated with the peptidyltransferase activity; labelled proteins are L27, L14, L15, L16, L2; at least L27 is located at the donor site, as shown by E. Collatz and A.P. Czernilofsky. Additional research has demonstrated that the S1 and S21 proteins, in association with the 3′-end of 16S ribosomal RNA, are involved in the initiation of translation.

Archaeal ribosomes

Archaeal ribosomes share the same general dimensions of bacteria ones, being a 70S ribosome made up from a 50S large subunit, a 30S small subunit, and containing three rRNA chains. However, on the sequence level, they are much closer to eukaryotic ones than to bacterial ones. Every extra ribosomal protein archaea have compared to bacteria has a eukaryotic counterpart, while no such relation applies between archaea and bacteria.

Eukaryotic ribosomes

Eukaryotes have 80S ribosomes located in their cytosol, each consisting of a small (40S) and large (60S) subunit. Their 40S subunit has an 18S RNA (1900 nucleotides) and 33 proteins. The large subunit is composed of a 5S RNA (120 nucleotides), 28S RNA (4700 nucleotides), a 5.8S RNA (160 nucleotides) subunits and 49 proteins.

eukaryotic cytosolic ribosomes (R. norvegicus) ribosome subunit rRNAs r-proteins 80S 60S 28S (4718 nt) 49 5.8S (160 nt) 5S (120 nt) 40S 18S (1874 nt) 33

During 1977, Czernilofsky published research that used affinity labeling to identify tRNA-binding sites on rat liver ribosomes. Several proteins, including L32/33, L36, L21, L23, L28/29 and L13 were implicated as being at or near the peptidyl transferase center.

Plastoribosomes and mitoribosomes

In eukaryotes, ribosomes are present in mitochondria (sometimes called mitoribosomes) and in plastids such as chloroplasts (also called plastoribosomes). They also consist of large and small subunits bound together with proteins into one 70S particle. These ribosomes are similar to those of bacteria and these organelles are thought to have originated as symbiotic bacteria. Of the two, chloroplastic ribosomes are closer to bacterial ones than mitochondrial ones are. Many pieces of ribosomal RNA in the mitochondria are shortened, and in the case of 5S rRNA, replaced by other structures in animals and fungi. In particular, Leishmania tarentolae has a minimalized set of mitochondrial rRNA. In contrast, plant mitoribosomes have both extended rRNA and additional proteins as compared to bacteria, in particular, many pentatricopetide repeat proteins.

The cryptomonad and chlorarachniophyte algae may contain a nucleomorph that resembles a vestigial eukaryotic nucleus. Eukaryotic 80S ribosomes may be present in the compartment containing the nucleomorph.

Making use of the differences

The differences between the bacterial and eukaryotic ribosomes are exploited by pharmaceutical chemists to create antibiotics that can destroy a bacterial infection without harming the cells of the infected person. Due to the differences in their structures, the bacterial 70S ribosomes are vulnerable to these antibiotics while the eukaryotic 80S ribosomes are not. Even though mitochondria possess ribosomes similar to the bacterial ones, mitochondria are not affected by these antibiotics because they are surrounded by a double membrane that does not easily admit these antibiotics into the organelle. A noteworthy counterexample is the antineoplastic antibiotic chloramphenicol, which inhibits bacterial 50S and eukaryotic mitochondrial 50S ribosomes. Ribosomes in chloroplasts, however, are different: Antibiotic resistance in chloroplast ribosomal proteins is a trait that has to be introduced as a marker, with genetic engineering.

Common properties

The various ribosomes share a core structure, which is quite similar despite the large differences in size. Much of the RNA is highly organized into various tertiary structural motifs, for example pseudoknots that exhibit coaxial stacking. The extra RNA in the larger ribosomes is in several long continuous insertions, such that they form loops out of the core structure without disrupting or changing it. All of the catalytic activity of the ribosome is carried out by the RNA; the proteins reside on the surface and seem to stabilize the structure.

High-resolution structure

The general molecular structure of the ribosome has been known since the early 1970s. In the early 2000s, the structure has been achieved at high resolutions, of the order of a few ångströms.

The first papers giving the structure of the ribosome at atomic resolution were published almost simultaneously in late 2000. The 50S (large prokaryotic) subunit was determined from the archaeon Haloarcula marismortui and the bacterium Deinococcus radiodurans, and the structure of the 30S subunit was determined from the bacterium Thermus thermophilus. These structural studies were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009. In May 2001 these coordinates were used to reconstruct the entire T. thermophilus 70S particle at 5.5 Å resolution.

Two papers were published in November 2005 with structures of the Escherichia coli 70S ribosome. The structures of a vacant ribosome were determined at 3.5 Å resolution using X-ray crystallography. Then, two weeks later, a structure based on cryo-electron microscopy was published, which depicts the ribosome at 11–15 Å resolution in the act of passing a newly synthesized protein strand into the protein-conducting channel.

The first atomic structures of the ribosome complexed with tRNA and mRNA molecules were solved by using X-ray crystallography by two groups independently, at 2.8 Å and at 3.7 Å. These structures allow one to see the details of interactions of the Thermus thermophilus ribosome with mRNA and with tRNAs bound at classical ribosomal sites. Interactions of the ribosome with long mRNAs containing Shine-Dalgarno sequences were visualized soon after that at 4.5–5.5 Å resolution. In 2023, a cryo-electron microscopy study reported a 1.55 Å structure of the Escherichia coli 70S ribosome in the translating state, providing near-atomic detail of rRNA modifications, tRNA-mRNA interactions, and ion coordination. The high-resolution map enabled identification of ribosomal polymorphism sites and visualization of transient chimeric hybrid states associated with tRNA translocation at approximately 2 Å resolution. These findings improved structural understanding of the ribosome's functional regions and offered valuable insights for antibiotic design.

In 2011, the first complete atomic structure of the eukaryotic 80S ribosome from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae was obtained by crystallography. The model reveals the architecture of eukaryote-specific elements and their interaction with the universally conserved core. At the same time, the complete model of a eukaryotic 40S ribosomal structure in Tetrahymena thermophila was published and described the structure of the 40S subunit, as well as much about the 40S subunit's interaction with eIF1 during translation initiation. Similarly, the eukaryotic 60S subunit structure was also determined from Tetrahymena thermophila in complex with eIF6. In addition, high-resolution cryo-EM structures of a thermophilic eukaryotic 80S ribosome captured in two rotational states at ~2.9 Å and ~3.0 Å resolution revealed atomistic details of the eukaryotic translocation mechanism and conformational dynamics of eEF2 during GTP hydrolysis.

Function

Ribosomes are minute particles consisting of RNA and associated proteins that function to synthesize proteins. Proteins are needed for many cellular functions, such as repairing damage or directing chemical processes. Ribosomes can be found floating within the cytoplasm or attached to the endoplasmic reticulum. Their main function is to convert genetic code into an amino acid sequence and to build protein polymers from amino acid monomers.

Ribosomes act as catalysts in two extremely important biological processes called peptidyl transfer and peptidyl hydrolysis. The "PT center is responsible for producing protein bonds during protein elongation".

In summary, ribosomes have two main functions: Decoding the message, and the formation of peptide bonds. These two functions reside in the ribosomal subunits. Each subunit is made of one or more rRNAs and many r-proteins. The small subunit (30S in bacteria and archaea, 40S in eukaryotes) has the decoding function, whereas the large subunit (50S in bacteria and archaea, 60S in eukaryotes) catalyzes the formation of peptide bonds, referred to as the peptidyl-transferase activity. The bacterial (and archaeal) small subunit contains the 16S rRNA and 21 r-proteins (Escherichia coli), whereas the eukaryotic small subunit contains the 18S rRNA and 32 r-proteins (Saccharomyces cerevisiae, although the numbers vary between species). The bacterial large subunit contains the 5S and 23S rRNAs and 34 r-proteins (E. coli), with the eukaryotic large subunit containing the 5S, 5.8S, and 25S/28S rRNAs and 46 r-proteins (S. cerevisiae; again, the exact numbers vary between species).

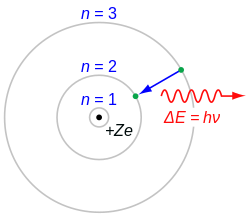

Translation

Ribosomes are the workplaces of protein biosynthesis, the process of translating mRNA into protein. The mRNA comprises a series of codons which are decoded by the ribosome to make the protein. Using the mRNA as a template, the ribosome traverses each codon (3 nucleotides) of the mRNA, pairing it with the appropriate amino acid provided by an aminoacyl-tRNA. Aminoacyl-tRNA contains a complementary anticodon on one end and the appropriate amino acid on the other. For fast and accurate recognition of the appropriate tRNA, the ribosome utilizes large conformational changes (conformational proofreading). The small ribosomal subunit, typically bound to an aminoacyl-tRNA containing the first amino acid methionine, binds to an AUG codon on the mRNA and recruits the large ribosomal subunit. The ribosome contains three RNA binding sites, designated A, P, and E. The A-site binds an aminoacyl-tRNA or termination release factors; the P-site binds a peptidyl-tRNA (a tRNA bound to the poly-peptide chain); and the E-site (exit) binds a free tRNA. Protein synthesis begins at a start codon AUG near the 5' end of the mRNA. mRNA binds to the P site of the ribosome first. The ribosome recognizes the start codon by using the Shine-Dalgarno sequence of the mRNA in prokaryotes and Kozak box in eukaryotes.

Although catalysis of the peptide bond involves the C2 hydroxyl of RNA's P-site adenosine in a proton shuttle mechanism, other steps in protein synthesis (such as translocation) are caused by changes in protein conformations. Since their catalytic core is made of RNA, ribosomes are classified as "ribozymes," and it is thought that they might be remnants of the RNA world.

In Figure 5, both ribosomal subunits (small and large) assemble at the start codon (towards the 5' end of the mRNA). The ribosome uses tRNA that matches the current codon (triplet) on the mRNA to append an amino acid to the polypeptide chain. This is done for each triplet on the mRNA, while the ribosome moves towards the 3' end of the mRNA. Usually in bacterial cells, several ribosomes are working parallel on a single mRNA, forming what is called a polyribosome or polysome.

Cotranslational folding

The ribosome is known to actively participate in the protein folding. The structures obtained in this way are usually identical to the ones obtained during protein chemical refolding; however, the pathways leading to the final product may be different. In some cases, the ribosome is crucial in obtaining the functional protein form. For example, one of the possible mechanisms of folding of the deeply knotted proteins relies on the ribosome pushing the chain through the attached loop.

Addition of translation-independent amino acids

Presence of a ribosome quality control protein Rqc2 is associated with mRNA-independent protein elongation. This elongation is a result of ribosomal addition (via tRNAs brought by Rqc2) of CAT tails: ribosomes extend the C-terminus of a stalled protein with random, translation-independent sequences of alanines and threonines.

Ribosome locations

Ribosomes are classified as being either "free" or "membrane-bound".

Free and membrane-bound ribosomes differ only in their spatial distribution; they are identical in structure. Whether the ribosome exists in a free or membrane-bound state depends on the presence of an ER-targeting signal sequence on the protein being synthesized, so an individual ribosome might be membrane-bound when it is making one protein, but free in the cytosol when it makes another protein.

Ribosomes are sometimes referred to as organelles, but the use of the term organelle is often restricted to describing sub-cellular components that include a phospholipid membrane, which ribosomes, being entirely particulate, do not. For this reason, ribosomes may sometimes be described as "non-membranous organelles".

Free ribosomes

Free ribosomes can move about anywhere in the cytosol, but are excluded from the cell nucleus and other organelles. Proteins that are formed from free ribosomes are released into the cytosol and used within the cell. Since the cytosol contains high concentrations of glutathione and is, therefore, a reducing environment, proteins containing disulfide bonds, which are formed from oxidized cysteine residues, cannot be produced within it.

Membrane-bound ribosomes

When a ribosome begins to synthesize proteins needed in certain organelles, the ribosome making this protein can become "membrane-bound". In eukaryotic cells this happens in a region of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) called the "rough ER". The newly produced polypeptide chains are inserted directly into the ER by the ribosome undertaking vectorial synthesis and are then transported to their destinations, through the secretory pathway. Bound ribosomes usually produce proteins that are used within the plasma membrane or are expelled from the cell via exocytosis.

Biogenesis

In bacterial cells, ribosomes are synthesized in the cytoplasm through the transcription of multiple ribosome gene operons. In eukaryotes, the process takes place both in the cell cytoplasm and in the nucleolus, which is a region within the cell nucleus. The assembly process involves the coordinated function of over 200 proteins in the synthesis and processing of the four rRNAs, as well as assembly of those rRNAs with the ribosomal proteins.

Origin

The ribosome may have first originated as a protoribosome, possibly containing a peptidyl transferase centre (PTC), in an RNA world, appearing as a self-replicating complex that only later evolved the ability to synthesize proteins when amino acids began to appear. Studies suggest that ancient ribosomes constructed solely of rRNA could have developed the ability to synthesize peptide bonds. In addition, evidence strongly points to ancient ribosomes as self-replicating complexes, where the rRNA in the ribosomes had informational, structural, and catalytic purposes because it could have coded for tRNAs and proteins needed for ribosomal self-replication. Hypothetical cellular organisms with self-replicating RNA but without DNA are called ribocytes (or ribocells).

As amino acids gradually appeared in the RNA world under prebiotic conditions, their interactions with catalytic RNA would increase both the range and efficiency of function of catalytic RNA molecules. Thus, the driving force for the evolution of the ribosome from an ancient self-replicating machine into its current form as a translational machine may have been the selective pressure to incorporate proteins into the ribosome's self-replicating mechanisms, so as to increase its capacity for self-replication.

Heterogeneous ribosomes

In 1958, Francis Crick famously proposed the "one gene-one ribosome-one protein hypothesis," where each ribosome carries the genetic information required to encode a single protein. Although discredited at that time, from the discovery of the first ribosomopathy Diamond–Blackfan Anemia in 1999, the ribosome has transitioned from a passive molecular machine to a dynamic macromolecular machine. Ribosomes are compositionally heterogeneous between species and even within the same cell, as evidenced by the existence of cytoplasmic and mitochondria ribosomes within the same eukaryotic cells. Certain researchers have suggested that heterogeneity in the composition of ribosomal proteins in mammals is important for gene regulation, i.e., the specialized ribosome hypothesis. However, this hypothesis is controversial and the topic of ongoing research.

Heterogeneity in ribosome composition was first proposed to be involved in translational control of protein synthesis by Vince Mauro and Gerald Edelman. They proposed the ribosome filter hypothesis to explain the regulatory functions of ribosomes. Evidence has suggested that specialized ribosomes specific to different cell populations may affect how genes are translated. Some ribosomal proteins exchange from the assembled complex with cytosolic copies suggesting that the structure of the in vivo ribosome can be modified without synthesizing an entire new ribosome.

Certain ribosomal proteins are absolutely critical for cellular life while others are not. In budding yeast, 14/78 ribosomal proteins are non-essential for growth, while in humans this depends on the cell of study. Other forms of heterogeneity include post-translational modifications to ribosomal proteins such as acetylation, methylation, and phosphorylation. Arabidopsis, Viral internal ribosome entry sites (IRESs) may mediate translations by compositionally distinct ribosomes. For example, 40S ribosomal units without eS25 in yeast and mammalian cells are unable to recruit the CrPV IGR IRES.

Heterogeneity of ribosomal RNA modifications plays a significant role in structural maintenance and/or function and most mRNA modifications are found in highly conserved regions. The most common rRNA modifications are pseudouridylation and 2'-O-methylation of ribose.

![{\displaystyle [{\hat {p}}_{i},{\hat {x}}_{j}]=-i\hbar \delta _{ij},}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a6de152aa445b7ca6653b9dd087ad604c2b8bf0e)